To evaluate musculoskeletal involvement and autoantibodies in pediatric leprosy patients.

Methods50 leprosy patients and 47 healthy children and adolescents were assessed according to musculoskeletal manifestations (arthralgia, arthritis, and myalgia), musculoskeletal pain syndromes (juvenile fibromyalgia, benign joint hypermobility syndrome, myofascial syndrome, and tendinitis), and a panel of autoantibodies and cryoglobulins. Health assessment scores and treatment were performed in leprosy patients.

ResultsAt least one musculoskeletal manifestation was observed in 14% of leprosy patients and in none of the controls. Five leprosy patients had asymmetric polyarthritis of small hands joints. Nerve function impairment was observed in 22% of leprosy patients, type 1 leprosy reaction in 18%, and silent neuropathy in 16%. None of the patients and controls presented musculoskeletal pain syndromes, and the frequencies of all antibodies and cyoglobulins were similar in both groups (p > 0.05). Further analysis of leprosy patients demonstrated that the frequencies of nerve function impairment, type 1 leprosy reaction, and silent neuropathy were significantly observed in patients with versus without musculoskeletal manifestations (p = 0.0036, p = 0.0001, and p = 0.309, respectively), as well as multibacillary subtypes in leprosy (86% vs. 42%, p = 0.045). The median of physicians’ visual analog scale (VAS), patients’ VAS, pain VAS, and Childhood Health Assessment Questionnaire (CHAQ) were significantly higher in leprosy patients with musculoskeletal manifestations (p = 0.0001, p = 0.002, p = 0002, and p = 0.001, respectively).

ConclusionsThis was the first study to identify musculoskeletal manifestations associated with nerve dysfunction in pediatric leprosy patients. Hansen's disease should be included in the differential diagnosis of asymmetric arthritis, especially in endemic regions.

Avaliar o envolvimento musculoesquelético e os autoanticorpos em pacientes pediátricos com hanseníase.

MétodosForam avaliados 50 pacientes com hanseníase e 47 crianças e adolescentes saudáveis de acordo com manifestações musculoesqueléticas (artralgia, artrite e mialgia), síndromes dolorosas musculoesqueléticas (fibromialgia juvenil, síndrome de hipermobilidade articular benigna, síndrome miofascial e tendinite) e painel de autoanticorpos e crioglobulinas. Escores de avaliação de saúde e tratamento foram realizados nos pacientes com hanseníase.

ResultadosPelo menos uma manifestação musculoesquelética foi observada em 14% dos pacientes com hanseníase e em nenhum controle. Dentre os pacientes com hanseníase, cinco tinham poliartrite assimétrica das pequenas articulações das mãos. Comprometimento da função do nervo foi observado em 22% dos pacientes com hanseníase, reação tipo I hansênica em 18% e neuropatia silenciosa em 16%. Nenhum dos pacientes e controles apresentou síndromes de dor musculoesquelética e as frequências dos anticorpos e crioglobulinas foram semelhantes nos dois grupos (p > 0,05). Comprometimentos da função nervosa, reação hansênica tipo I e neuropatia silenciosa foram observados em pacientes com vs sem manifestações musculoesqueléticas (p = 0,0036, p = 0,0001 e p = 0,309, respectivamente), bem como subtipos de hanseníase multibacilar (86% vs 42%, p = 0,045). A escala visual analógica (EVA) do médico, dos pacientes, e da dor e o Questionário de Avaliação de Saúde Infantil foram maiores em pacientes com manifestações musculoesqueléticas (p = 0,0001, p = 0,002, p = 0002 e p = 0,001, respectivamente).

ConclusãoEste foi o primeiro estudo a identificar manifestações musculoesqueléticas associadas com disfunção de nervos periféricos em pacientes pediátricos. A hanseníase deve ser incluída no diagnóstico diferencial de artrite assimétrica, principalmente em regiões endêmicas.

Leprosy is a chronic infectious disease caused by Mycobacterium leprae. It is considered a major public health issue in developing countries and has been rarely described in pediatric population, which comprises 6% to 14% of all leprosy cases,1,2 with an average of 7% in Brazil.3

The important clinical signs of leprosy are hypopigmented or reddish localized skin lesions with loss of sensation and peripheral nerves involvement.4,5 Musculoskeletal manifestations were described in adult leprosy patients, especially acute and chronic arthritis6–12 and arthralgia,8 and these involvements were rarely described in the pediatric leprosy population.13,14

Autoantibodies were also studied in adult leprosy patients, especially antinuclear antibody (ANA)9 and antiphospholipid.15 Moreover, there is no study that has simultaneously assessed musculoskeletal involvement and autoantibodies in pediatric leprosy patients.

Therefore, this was a cross-sectional study that investigated the musculoskeletal involvement and autoantibodies in pediatric leprosy patients and healthy controls. In addition, the possible associations of musculoskeletal manifestations in leprosy children and adolescents with demographic data, leprosy manifestations, health assessment scores, autoantibodies, and treatment were evaluated.

Patients and methodsFrom January of 2010 to October of 2012, 56 leprosy patients were followed up at the Dermatology Service of the Hospital Universitário Julio Muller, from the Universidade Federal do Mato Grosso, Cuiabá, Brazil. Fifty leprosy patients agreed to participate in this study. All patients were diagnosed in accordance with the National Leprosy Program guidelines5 and the Ridley-Jopling classification criteria,16 as borderline-borderline (BB), borderline-lepromatous (BL), lepromatous-lepromatous (LL), borderline-tuberculoid (BT), tuberculoid-tuberculoid (TT), or indeterminate leprosy (IL). The control group included 47 healthy children and adolescent of the Escola Estadual de 1° e 2° graus Bela Vista, Cuiabá, Mato Grosso, Brazil. The ethical committees of the Hospital Universitário Julio Muller and of the Hospital das Clínicas da Universidade de São Paulo approved this study, and an informed consent was obtained from all participants and legal guardians.

Demographic data and socio-economic classesDemographic data included current age and gender. Brazilian socioeconomic classes were classified in accordance with the Associação Brasileira dos Institutos de Pesquisa de Mercados criteria.17

Musculoskeletal manifestationsMusculoskeletal manifestations were defined according to arthralgia (diffuse joint pain or tenderness without evidence of inflammation), arthritis (swelling within a joint, or limitation in the range of joint movement with joint pain or tenderness),18 and myalgia (muscle pain or tenderness in one or more limbs without evidence of inflammation). Arthritis were classified according to the number of joints (oligoarticular lower than four arthritides and polyarticular [equal to or greater than five arthritides]) and the duration (acute [lower than six weeks] and chronic [equal to or greater than six weeks]).18

Musculoskeletal pain syndromesThe following musculoskeletal pain syndromes were diagnosed during musculoskeletal examination: juvenile fibromyalgia,19 myofascial syndrome, and tendinitis.20–22 Juvenile fibromyalgia was diagnosed in accordance with Yunus and Masi criteria.19 Myofascial syndrome was diagnosed according to active trigger points, which is defined as painful points in taut bands of muscle fibers. If pressured, these points induce reported pain that is reproducible and that affects specific places for each muscle.20–22

Other findings in musculoskeletal physical examinationJoint hypermobility (JH) was diagnosed according to the criteria proposed by Beighton. Benign joint hypermobility syndrome was defined as JH combined with musculoskeletal pain and five of nine criteria.23

Clinical assessment of leprosyClinical assessment of leprosy was performed in accordance with the Brazilian Leprosy Program guidelines.5 Nerve function impairment is a clinically detectable loss of motor, sensory, or autonomic peripheral nerve function. Type 1 (reversal) leprosy reaction is defined as nerve inflammation with loss of sensory and motor functions and/or redness and swelling in pre-existing skin lesion and in new lesions. Silent neuropathy is defined as the impairment of nerve function without any nerve pain or tenderness. Type 2 (erythema nodosum leprosum) leprosy reaction is defined as a sudden appearance of superficial or deep crops on new tender subcutaneous nodules.5

Health assessment scores and treatment in leprosy patientsAll leprosy patients were evaluated regarding physician's global assessment, patient's global assessment, and pain using the 10cm Visual Analog Scale (VAS)24 and the Childhood Health Assessment Questionnaire (CHAQ).25

Data concerning leprosy treatment included: prednisone therapy, mutibacillary therapy (rifampicin, dapsone and clofazimine), and paucibacillary therapy (rifampicine and dapsone).5

Autoantibodies and cryoglobulinsThe laboratory exams were performed by a technician who was blinded to the results of leprosy and musculoskeletal manifestations. The following serum autoantibodies were measured at study admission: ANA by indirect immunofluorescence on human cell epithelioma (HEp-2) cells (GMK - United States) and staining reactivity at ≥ 1:80 serum dilution defined as positive; anti-double-stranded DNA (anti-ds DNA) by in-house indirect immunofluorescence using Crithidia luciliae as substrate (GMK – United States) with a cut-off value of 1:10; anti-Ro and anti-La by fluorometry (Phadia - Sweden) with a cut-off < 10.1; anticardiolipin (aCL) isotypes IgG and IgM by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; Phadia - Sweden), with a cut-off value of 20 GPL and/or MPL. Lupus anticoagulant (LAC) was assessed by the dilute Russell's viper venom time with a cut-off value < 1.15 and confirmatory testing with a cut-off value < 1.21 (Siemens - Germany). Cryoglobulin was performed by in-house gel immunoelectrophoresis. HLA B27 and rheumatoid factor (RF) detections were performed by in-house real-time polymerase chain reaction assay (Arup Laboratories - USA) and by immunoturbidimetric assays (Wiener - Argentina; cut-off < 20 UI/mL) in patients and controls with arthralgia and/or arthritis.

Statistical analysisResults were presented as mean ± standard deviation or median (range) for continuous variables, and as number (%) for categorical variables. Data were compared by Student's t-test or Mann-Whitney's test for continuous variables. For categorical variables, the differences were assessed by Fisher's exact test. In all statistical tests, the level of significance was set at 5% (p < 0.05).

ResultsLeprosy patients and healthy controlsMusculoskeletal and leprosy manifestations, and musculoskeletal pain syndromesAt least one musculoskeletal manifestation (arthralgia, arthritis, and/or myalgia) was observed in 14% of leprosy patients, and none was observed in healthy controls. Five leprosy patients had asymmetric polyarthritis of small joints of the hands (metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints), with median duration of 12 months (ranging from 15 days to 36 months). Four patients with borderline leprosy had chronic polyarthritis and morning stiffness.

The most frequent leprosy manifestations were hypopigmented or reddish localized skin lesions with loss of sensation, particularly of touch and temperature, observed in 94% of all leprosy patients. Nerve function impairment was observed in 22% of the leprosy patients; type 1 leprosy reaction, in 18%; and silent neuropathy, in 16%. No leprosy patient had cutaneous vasculitis and type 2 (erythema nodosum leprosum) leprosy reaction.

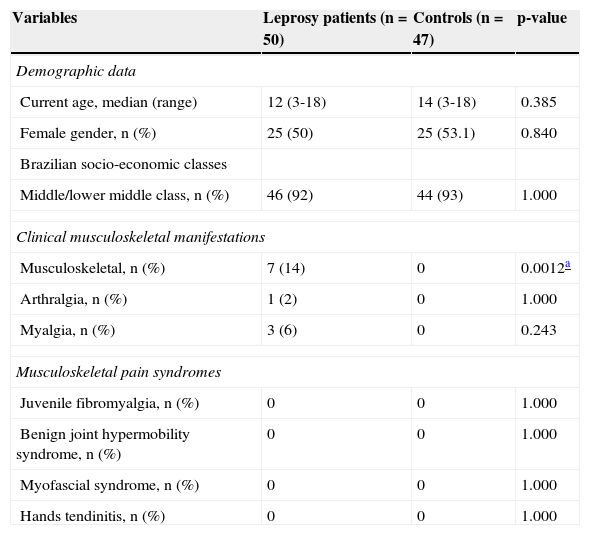

None of the patients and controls had juvenile fybromialgia, benign joint hypermobility syndrome, myofascial syndrome, and tendinitis in the hands (Table 1).

Demographic data, clinical musculoskeletal manifestations, and musculoskeletal pain syndromes in leprosy patients and healthy controls.

| Variables | Leprosy patients (n = 50) | Controls (n = 47) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic data | |||

| Current age, median (range) | 12 (3-18) | 14 (3-18) | 0.385 |

| Female gender, n (%) | 25 (50) | 25 (53.1) | 0.840 |

| Brazilian socio-economic classes | |||

| Middle/lower middle class, n (%) | 46 (92) | 44 (93) | 1.000 |

| Clinical musculoskeletal manifestations | |||

| Musculoskeletal, n (%) | 7 (14) | 0 | 0.0012a |

| Arthralgia, n (%) | 1 (2) | 0 | 1.000 |

| Myalgia, n (%) | 3 (6) | 0 | 0.243 |

| Musculoskeletal pain syndromes | |||

| Juvenile fibromyalgia, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 1.000 |

| Benign joint hypermobility syndrome, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 1.000 |

| Myofascial syndrome, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 1.000 |

| Hands tendinitis, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 1.000 |

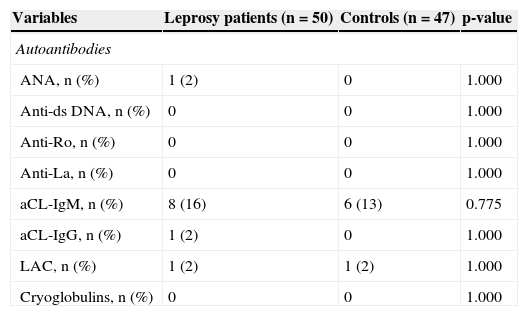

The frequencies of all antibodies (ANA, anti-ds DNA, anti-Ro, anti-La, aCL-IgM, aCl-IgG, and LAC) and cyoglobulins were similar in leprosy patients and controls (Table 2). HLA B27 test were negative in all patients with arthralgia and/or arthritis. RF was positive in two out of five patients with arthralgia and/or arthritis.

Autoantibodies and cryoglobulins in leprosy patients and healthy controls.

| Variables | Leprosy patients (n = 50) | Controls (n = 47) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Autoantibodies | |||

| ANA, n (%) | 1 (2) | 0 | 1.000 |

| Anti-ds DNA, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 1.000 |

| Anti-Ro, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 1.000 |

| Anti-La, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 1.000 |

| aCL-IgM, n (%) | 8 (16) | 6 (13) | 0.775 |

| aCL-IgG, n (%) | 1 (2) | 0 | 1.000 |

| LAC, n (%) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 1.000 |

| Cryoglobulins, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 1.000 |

ANA, antinuclear antibody; anti-ds DNA, anti-double-stranded DNA antibody; anti-Ro, anti-Ro antibody; anti-La, anti-La antibody; aCL, anticardiolipin antibody; IgM, immunoglobulin M; IgG, immunoglobulin G; LAC, lupus anticoagulant.

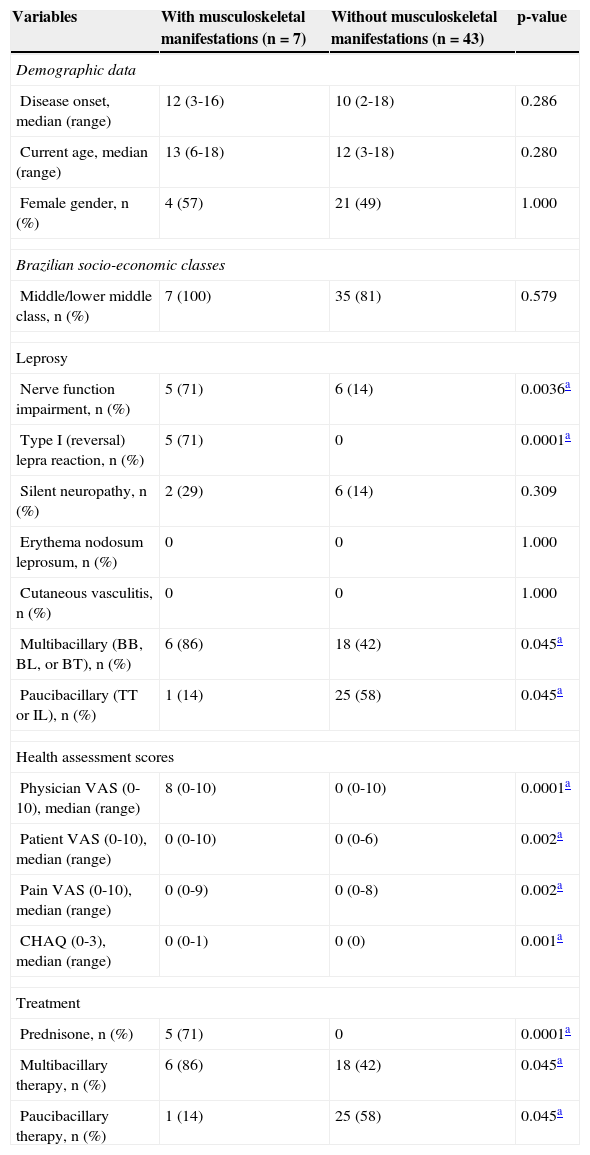

The frequencies of nerve function impairment, type 1 leprosy reaction, and silent neuropathy were significantly observed in leprosy patients with musculoskeletal manifestations versus those without (71% vs. 14%, p = 0.0036; 71% vs. 0%, p = 0.0001; 29% vs. 14%, p = 0.309; respectively), as well as multibacillary subtypes in leprosy patients with musculoskeletal manifestations (86% vs. 42%, p = 0.045) (Table 3).

Demographic data, leprosy clinical manifestations, health assessment scores, and treatment in leprosy patients with and without musculoskeletal manifestations.

| Variables | With musculoskeletal manifestations (n = 7) | Without musculoskeletal manifestations (n = 43) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic data | |||

| Disease onset, median (range) | 12 (3-16) | 10 (2-18) | 0.286 |

| Current age, median (range) | 13 (6-18) | 12 (3-18) | 0.280 |

| Female gender, n (%) | 4 (57) | 21 (49) | 1.000 |

| Brazilian socio-economic classes | |||

| Middle/lower middle class, n (%) | 7 (100) | 35 (81) | 0.579 |

| Leprosy | |||

| Nerve function impairment, n (%) | 5 (71) | 6 (14) | 0.0036a |

| Type I (reversal) lepra reaction, n (%) | 5 (71) | 0 | 0.0001a |

| Silent neuropathy, n (%) | 2 (29) | 6 (14) | 0.309 |

| Erythema nodosum leprosum, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 1.000 |

| Cutaneous vasculitis, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 1.000 |

| Multibacillary (BB, BL, or BT), n (%) | 6 (86) | 18 (42) | 0.045a |

| Paucibacillary (TT or IL), n (%) | 1 (14) | 25 (58) | 0.045a |

| Health assessment scores | |||

| Physician VAS (0-10), median (range) | 8 (0-10) | 0 (0-10) | 0.0001a |

| Patient VAS (0-10), median (range) | 0 (0-10) | 0 (0-6) | 0.002a |

| Pain VAS (0-10), median (range) | 0 (0-9) | 0 (0-8) | 0.002a |

| CHAQ (0-3), median (range) | 0 (0-1) | 0 (0) | 0.001a |

| Treatment | |||

| Prednisone, n (%) | 5 (71) | 0 | 0.0001a |

| Multibacillary therapy, n (%) | 6 (86) | 18 (42) | 0.045a |

| Paucibacillary therapy, n (%) | 1 (14) | 25 (58) | 0.045a |

BB, borderline-borderline; BL, borderline-lepromatous; BT, borderline-tuberculoid; TT, tuberculoid-tuberculoid; IL, indeterminate leprosy; VAS, visual analog scale; CHAQ, Childhood Health Assessment Questionnaire.

The median of physicians’ VAS, patients’ VAS, pain VAS, and CHAQ were significantly higher in leprosy patients with musculoskeletal manifestations versus those without these alterations (p = 0.0001, p = 0.002, p = 002, and p = 0.001, respectively). Leprosy patients with musculoskeletal manifestations were significantly treated with prednisone and multibacillary therapies compared with patients without these manifestations (71% vs. 0%, p = 0.0001; 86% vs. 42%, p = 0.045) (Table 3).

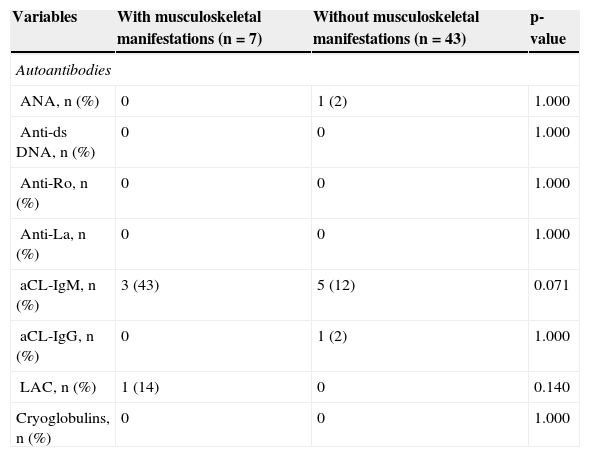

The frequencies of all antibodies (ANA, anti-ds DNA, anti-Ro, anti-La, aCL-IgM, aCl-IgG, and LAC) and cryoglobulins were similar in leprosy patients with and without musculoskeletal manifestations (Table 4).

Autoantibodies and cryoglobulins in leprosy patients with and without musculoskeletal manifestations.

| Variables | With musculoskeletal manifestations (n = 7) | Without musculoskeletal manifestations (n = 43) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Autoantibodies | |||

| ANA, n (%) | 0 | 1 (2) | 1.000 |

| Anti-ds DNA, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 1.000 |

| Anti-Ro, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 1.000 |

| Anti-La, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 1.000 |

| aCL-IgM, n (%) | 3 (43) | 5 (12) | 0.071 |

| aCL-IgG, n (%) | 0 | 1 (2) | 1.000 |

| LAC, n (%) | 1 (14) | 0 | 0.140 |

| Cryoglobulins, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 1.000 |

ANA, antinuclear antibody; anti-ds DNA, anti-double-stranded DNA antibody; anti-Ro, anti-Ro antibody; anti-La, anti-La antibody; aCL, anticardiolipin antibody; IgM, immunoglobulin M; IgG, immunoglobulin G; LAC, lupus anticoagulant.

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this was the first study in a pediatric leprosy population that clearly observed musculoskeletal manifestations, especially asymmetric polyarthritis, associated with severe disease and nerve function impairment, without autoantibodies production.

The great advantage of the present study design was the systematic evaluation of leprosy and musculoskeletal manifestations, pain syndromes, and a panel of autoantibodies, including standardized definitions18–23 and excluding periarticular pain,20–22 in a leprosy population of one state in Midwestern Brazil. Additionally, a healthy control group with the same age, gender, and socio-economic class, using the same protocol, was included.

Importantly, musculoskeletal involvement is the third most frequent manifestation in adult leprosy patients.10 Arthritis was described in 4% to 79%8,10 of these patients, and may be divided into four subtypes: Charcots joints, septic arthritis, acute arthritis, and chronic arthritis.10 Asymmetric polyarthritis generally involves metacarpophalangeal joints and proximal and distal interphalangeal joints,7 as observed in the present five pediatric leprosy patients. Furthermore, chronic polyarthritis of the hands mimicking rheumatoid arthritis was also reported in a young middle-aged male with type 1 leprosy reaction.10

This joint involvement is generally ignored in children and adolescents with leprosy, and chronic polyarthritis may mimic pediatric autoimmune diseases, especially juvenile idiopathic arthritis,7,13 acute leukemia,26 and childhood systemic lupus erythematosus.27 Of note, these musculoskeletal manifestations were rarely reported in the two leprosy cases that involved peripheral and hand joints,13 and also in one case associated with erythema nodusum that was previously evidenced by this group.14

Musculoskeletal pain syndromes were not observed in this population of leprosy patients and controls, as also described in the present healthy and obese adolescents, with a prevalence ranging from 0% to 10%.20–22 Additionally, no tendinitis of the hand associated with joint involvement was observed.

Interestingly, none of the present patients had joint hypermobility, although this abnormality has been reported in up to 20% of pediatric population.20,21 This alteration is more frequent in schoolchildren, with reduced prevalence in adolescents and adults. In fact, the present leprosy patients and healthy controls were mainly adolescents, which may have contributed to the absence of joint hypermobility, as also observed in another study by the authors.22

Autoantibodies were rarely observed in the present pediatric leprosy patients. IgM anticardiolipin was the most frequent autoantibodies observed in leprosy patients without autoimmune thrombosis (13%), as also observed in adult leprosy. This fact differed from the present patients with childhood systemic lupus erythematosus, juvenile dermatomyositis,28 and RASopathies,29 which presented up to 93%, 59%, and 52% of a variety of organ-specific and non organ-specific autoantibodies, respectively.

Leprosy is a chronic granulomatous infection that occurs mainly with cutaneous and neurological manifestations,4,5 as observed in the present patients with and without musculoskeletal involvement. This disease may affect daily life activities and health-related quality of life in adult patients,30 as observed herein.

Remarkably, type 1 leprosy reactions with nerve function impairment were related to severe disease,5 and these abnormalities were also associated with musculoskeletal manifestations, indicating a simultaneous involvement of nerves and joints that needed immunosuppressant and multibacillary treatment. Moreover, these patients could present permanent joint damage with swan neck deformities, mallet finger, and/or ulnar drift,10 which requires a rigorous and prolonged follow-up.

In conclusion, this was the first study to identify a high frequency of musculoskeletal manifestations associated with nerve dysfunction in pediatric leprosy patients. Hansen's disease should be included in the differential diagnosis of asymmetric arthritis, especially in endemic regions.

FundingThis study was supported by the Doutorado Inter Institucional (DINTER) of the Pediatric Department (UFMT-FMUSP), by the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq, under grant No. 302724/2011-7 to CAS), by a Federico Foundation grant to CAS, and by the Núcleo de Apoio à Pesquisa “Saúde da Criança e do Adolescente” of the Universidade de São (NAP-CriAd-SP).

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The authors would like to thank all the colleagues of the University Hospital of Cuiabá, Brazil, and Dr. Ulysses Dória Filho for assistance in statistical analysis.

Please cite this article as: Neder L, Rondon DA, Cury SS, da Silva CA. Musculoskeletal manifestations and autoantibodies in children and adolescents with leprosy. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2014;90:457–63.