To identify and describe the protocols and clinical outcomes of urotherapy interventions in children and adolescents with bladder bowel dysfunction.

MethodSystematic review carried out in June 2018 on Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online (MEDLINE), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL),Excerpta Medica dataBASE (EMBASE), Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciELO), Cochrane Library, and PsycInfo databases. Clinical trials and quasi-experimental studies carried out in the last ten years in children and/or adolescents with bladder and bowel symptoms and application of at least one component of urotherapy were included.

ResultsThirteen clinical trials and one quasi-experimental study were included, with moderate methodological quality. The heterogeneity of the samples and of the methodological design of the articles prevented the performance of a meta-analysis. The descriptive analysis through simple percentages showed symptom reduction and improvement of uroflowmetry parameters. The identified urotherapy components were: educational guidance, water intake, caffeine reduction, adequate voiding position, pelvic floor training, programmed urination, and constipation control/management.

ConclusionThis review indicates positive results in terms of symptom reduction and uroflowmetry parameter improvement with standard urotherapy as the first line of treatment for children and adolescents with bladder bowel dysfunction. It is recommended that future studies bring contributions regarding the frequency, number, and time of urotherapy consultations.

Identificar e descrever os protocolos e desfechos clínicos das intervenções de uroterapia em crianças e adolescentes com disfunção vesical e intestinal.

MétodoRevisão sistemática realizada em junho de 2018 nas bases Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online (MEDLINE), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL),Excerpta Medica dataBASE (EMBASE), Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciELO), Cochrane Library e PsycInfo. Foram incluídos ensaios clínicos e estudos quase-experimentais dos últimos 10 anos, em crianças e/ou adolescentes com sintoma urinário e intestinal e aplicação de no mínimo um componente de uroterapia.

Resultados13 ensaios clínicos e 1 estudo quase-experimental foram incluídos, sendo a qualidade metodológica moderada. A heterogeneidade da amostra e de delineamento metodológico dos artigos impediu a realização de meta-análise. A análise descritiva por meio de percentual simples demonstrou redução dos sintomas e melhora dos parâmetros de urofluxometria. Os componentes de uroterapia identificados foram: orientação educacional, ingestão hídrica, redução de cafeína, posicionamento adequado para eliminação, treinamento do assoalho pélvico, micção programada e controle/manejo da constipação.

ConclusãoEsta revisão sinaliza resultados positivos em termos de redução de sintomas e melhora nos parâmetros de urofluxometria com aplicação de uroterapia padrão como primeira linha de tratamento nos casos de crianças e adolescentes com disfunção vesical e intestinal. Recomenda-se que estudos futuros tragam contribuições no que tange a frequência, número e tempo para as consultas de uroterapia.

Bladder and bowel dysfunction (BBD) is defined as the combination of at least one of bowel symptoms (e.g., constipation and encopresis) associated with one or more lower urinary tract symptom (LUTS), which include symptoms related to alterations in the storage phases (examples: urinary incontinence and urgency), bladder emptying (examples: hesitation and weak urinary flow) and/or other symptoms (examples: urinary restraint maneuvers and pain when urinating).1,2

In epidemiological terms, the prevalence of BBD and LUTS has clinical relevance in the pediatric context, since they affect a significant percentage (44.3%) of children and adolescents considered healthy from the urological point of view, i.e., they do not have structural alterations in the genitourinary or neurological systems.1–3 They are exposed to complications such as incontinence-associated dermatitis, incomplete bladder emptying, urinary tract infections (UTIs), and vesicoureteral reflux, impairing upper urinary tract function.1,2 Moreover, BBD has a negative impact on the psychosocial dimension, which can lead to social isolation, anxiety, and depression.2,4,5

Urotherapy is the first-line treatment in cases of BBD and consists of a non-surgical and non-pharmacological approach.2 It is classified as standard urotherapy or specific urotherapy. Standard urotherapy involves information and demystification regarding the lower urinary tract (LUT) function, instructions on how to resolve specific LUTS for each case, behavioral modification (regular bowel and urinary habits, adequate posture in the toilet for voiding, etc.) guidelines on healthy lifestyle (adequate water intake, caffeine reduction, high fiber diet, etc.), programming intervals between urinations, recording of voiding symptoms and habits, identification of the pelvic floor musculature, and systematic clinical follow-up. Specific urotherapy includes pelvic floor relaxation techniques, biofeedback, electrostimulation, and clean intermittent catheterization. Additional interventions to urotherapy involve psychotherapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy.1,2,6,7

Several studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of urotherapy in reducing BBD symptoms. It is a therapy that is effective both in the reduction of LUTS, functional intestinal constipation (FIC), and UTI, as well as in the improvement of uroflowmetry parameters.8–13

This review is necessary because standard urotherapy is the first-line of treatment in BBD and, although it is well mentioned in the treatment of different groups of symptoms, it is seldom described, so there are few specific protocols for its application, regarding the number and frequency of the consultations, the duration of consultation, the content addressed in each session, or adopted strategies. It is also necessary to make an analysis of its effectiveness regarding symptom control in the studied population, since the studies are usually focused on a specific group of symptoms and not in the overall context of BBD, and aim at comparing this therapy with specific urotherapy techniques and not with a placebo or untreated control group.

This review was carried out according to the PICO14 strategy, in which P (participants) were children and adolescents with BBD; I (interventions) were one or more components of standard urotherapy; C (comparison) were comprised of control groups, surgical procedures, drug therapy, biofeedback, electrostimulation, alarms; O (outcomes) were symptom reduction and/or changes in the patterns of diagnostic examinations. The following research question was asked: “What are the clinical results/outcomes of urotherapy interventions applied to children and adolescents with BBD and what is the format or components of the applied protocol?”

Thus, the aim of this review was to identify and describe the protocols and clinical outcomes of urotherapy interventions applied to children and adolescents with BBD.

MethodThis is a systematic literature review, whose protocol was submitted to the PROSPERO platform under ID CRD42019121198.

The inclusion criteria used in the search were: randomized and controlled clinical trials and quasi-experimental studies; study population consisting of children and/or adolescents; sample with at least one urinary symptom associated with at least one intestinal symptom; application of (at least) one standard urotherapy component; articles published in the last ten years; articles published in English, Spanish, and/or Portuguese; articles available as full text or obtained through request to authors.

The exclusion criteria comprised: a sample consisting of children with lower urinary tract symptoms due to neurological dysfunction and studies that addressed only surgical, drug, or specific urotherapy interventions.

The search was carried out in June of 2018 at the databases: Medical Analysis and Retrieved System Online (MEDLINE/PubMed), CINAHL, EMBASE, Web of Science (Scientific Electronic Library Online – SciELO), The Cochrane Library, and PsycInfo.

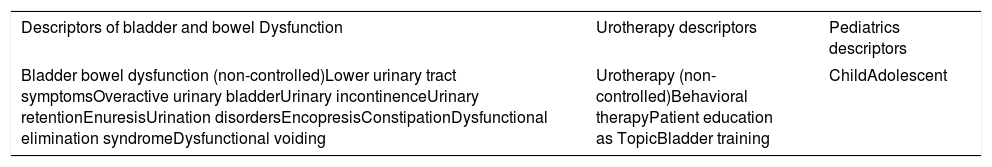

The descriptors used in the search are described in Table 1. The descriptors contained in each column (BBD, urotherapy, and pediatrics) were included with the “OR” Boolean operator between them. The group of descriptors of each category was crossed with the other groups using the operator “AND”. The publication period, language, study in humans, and study type filters were used in the databases that had these commands.

Search strategy for urotherapy studies in the treatment of children and adolescents with bladder and bowel dysfunction: a systematic review. Brasília, Brazil, 2019.

| Descriptors of bladder and bowel Dysfunction | Urotherapy descriptors | Pediatrics descriptors |

|---|---|---|

| Bladder bowel dysfunction (non-controlled)Lower urinary tract symptomsOveractive urinary bladderUrinary incontinenceUrinary retentionEnuresisUrination disordersEncopresisConstipationDysfunctional elimination syndromeDysfunctional voiding | Urotherapy (non-controlled)Behavioral therapyPatient education as TopicBladder training | ChildAdolescent |

The overall search result for each database was transferred into a folder in Mendeley® Reference Manager (Mendeley®, Elsevier, Amsterdam). The articles contained in all folders were moved to a single folder, where duplicates generated by journals indexed on more than one database were automatically deleted. All titles and abstracts were read after the eligibility criteria were applied. The articles considered eligible and those of which the summary did not explicitly show the presence of the inclusion criteria were read in full.

The data extracted from the selected articles were organized in an Excel (Excel®, Microsoft, WA, USA) spreadsheet, following the Checklist Consolidation of the Standards of Reports Trial – CONSORT,15 as they were clinical trials.

The title and abstract reading and later, the full-text reading phases were carried out by two independent reviewers and, in case of disagreements, they were resolved through discussion of the topic and consensus. A third reviewer solved the deadlocks in the selection of articles and doubts during the data extraction process.

The primary variables analyzed were BBD symptoms (urinary incontinence, nocturnal enuresis, urinary tract infection, constipation, fecal incontinence/encopresis, post-voiding residue, voiding symptoms, delayed urination, and urinary urgency) and uroflowmetry parameters (urinary volume, post-voiding residue, mean flow, maximum flow, time of flow, and bladder capacity), according to the analysis shown in each study.

The quality and bias risk assessment of the studies was concomitantly carried out by two reviewers, by debating each analyzed item. To classify them, the method and results sections of each publication were re-read and evaluated using the modified Jadad scale (score of 0–5, with 5 being the highest quality and below 3 considered low quality)16 and the Cochrane Collaboration tool for bias risk assessment (it classifies types of selection, performance, detection, attrition, and reporting bias, classifying as low risk, high risk, and uncertain risk).17 Both tools evaluate the process of randomization, blinding, loss of data and, in the Cochrane tool, presentation of outcome.

To analyze the resolution of the symptoms studied in each publication, after standard urotherapy, the percentage of participants who did not have the particular symptom after the therapy was calculated. For the same symptom analyzed in more than one article, the arithmetic mean of resolution percentages of each study was obtained, yielding a mean positive response to therapy for each symptom. The percentage calculation was also applied to compare the reduction of post-voiding residue verified in publications that analyzed this parameter in uroflowmetry. Regarding the uroflowmetry parameters, data were presented as mean and standard deviation, before and after urotherapy, followed by a descriptive analysis of the observed alterations.

The analyzed variables were organized into two tables, one of symptoms and one of uroflowmetry parameters. The data related to the components of the urotherapy protocol applied in each study were descriptively analyzed.

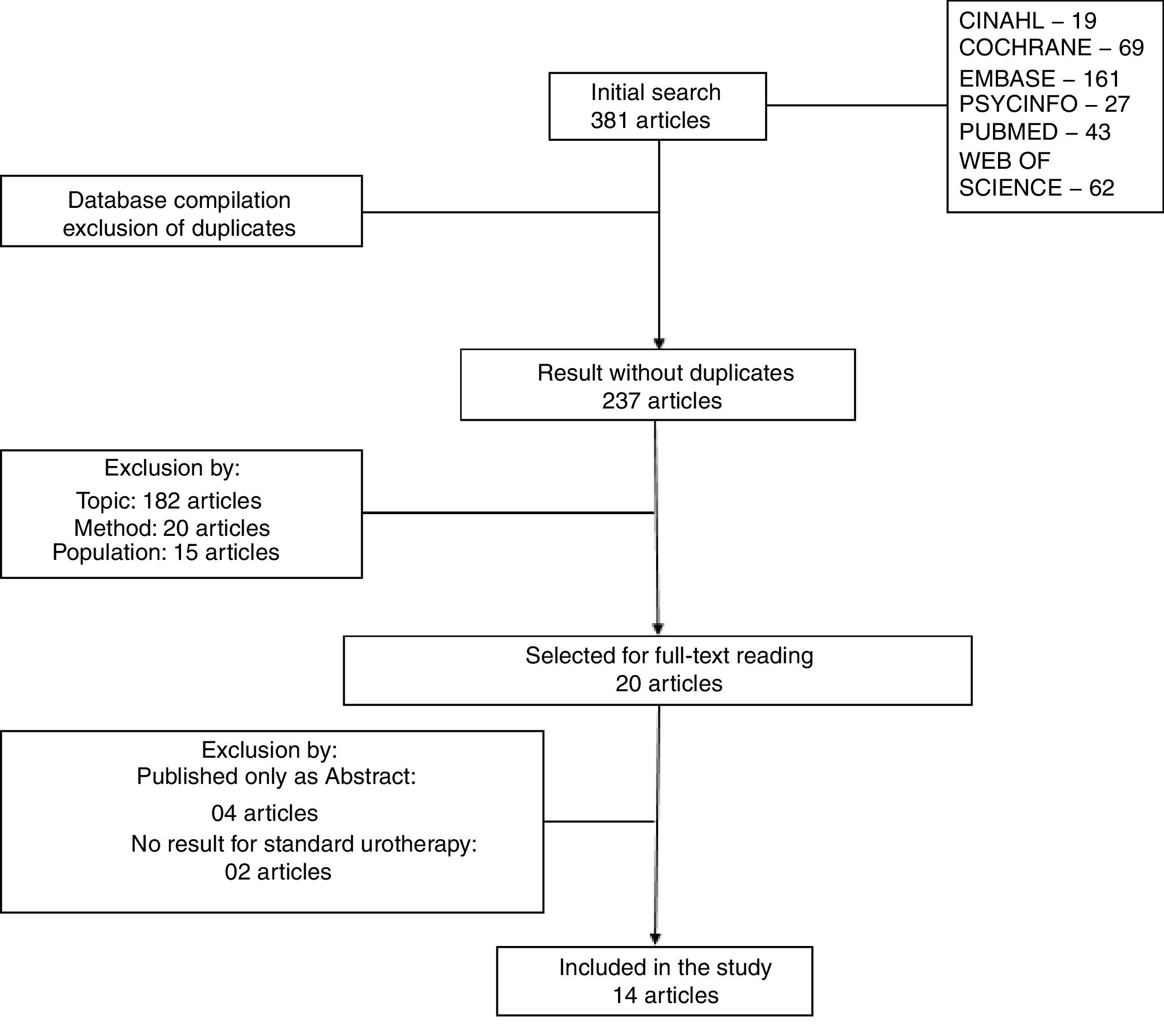

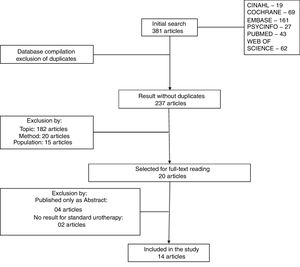

ResultsThe sample of this review consisted of 14 studies. Fig. 1 shows the selection flow of the articles.

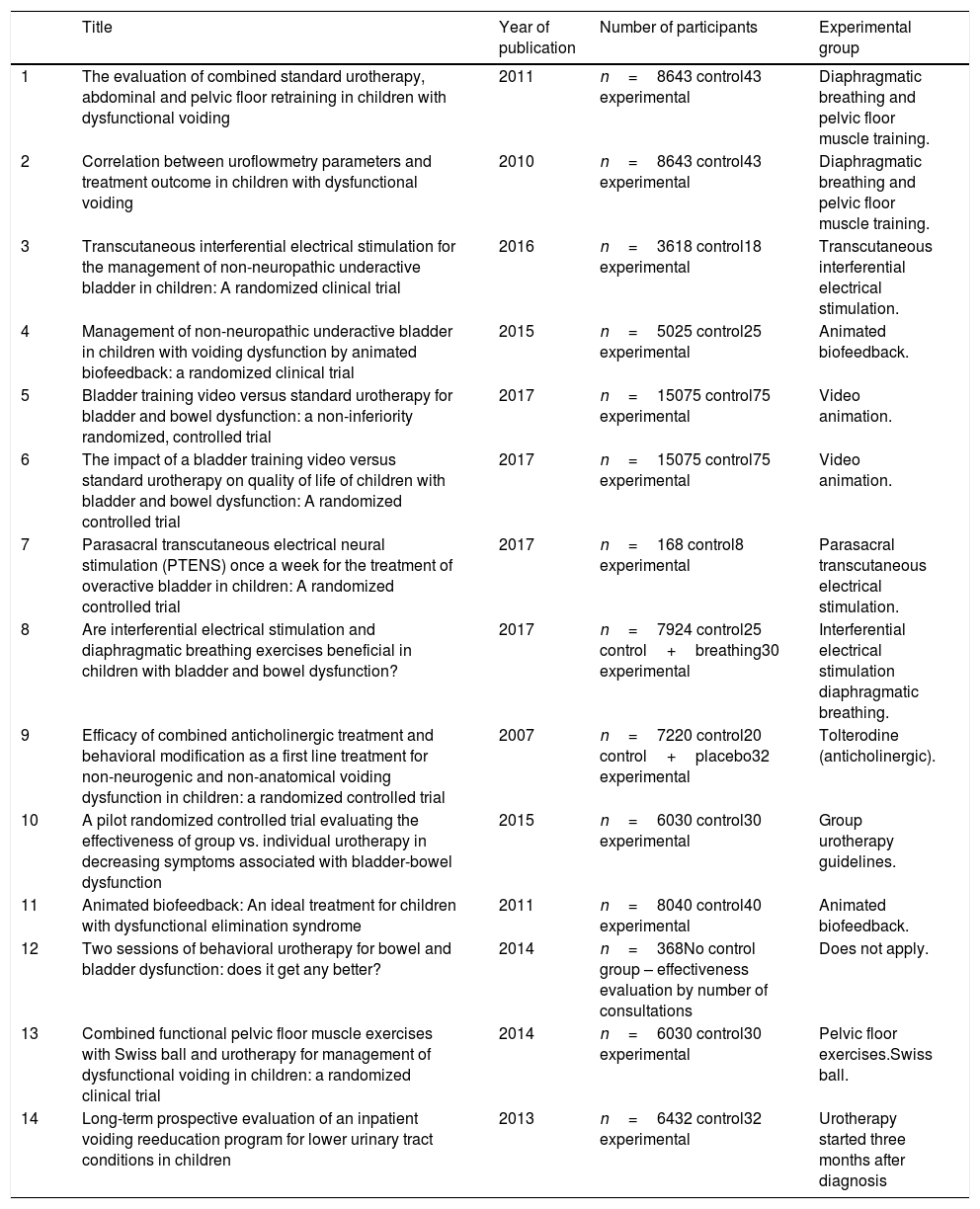

Only four articles were published in the first five years of the search. Eight articles compared standard urotherapy with standard+specific urotherapy.18–25 One study compared standard urotherapy with standard urotherapy+anticholinergic therapy.26 Three articles compared standard urotherapy with a traditional approach (individual dialog consultation) with alternative techniques for urotherapy application (video animation and group approach).10,27,28 One article compared symptom reduction in children who received urotherapy shortly after the diagnosis with those who received therapy three months after the diagnosis29 and one article analyzed response to urotherapy at each child's appointment, as well as the percentage of adherence to the return consultations according to the number of visits.30Table 2 shows the 14 articles that comprised the sample.

Characterization of the articles that constitute the sample. Urotherapy in the treatment of children and adolescents with bladder and bowel dysfunction: a systematic review. Brasília, Brazil, 2019.

| Title | Year of publication | Number of participants | Experimental group | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | The evaluation of combined standard urotherapy, abdominal and pelvic floor retraining in children with dysfunctional voiding | 2011 | n=8643 control43 experimental | Diaphragmatic breathing and pelvic floor muscle training. |

| 2 | Correlation between uroflowmetry parameters and treatment outcome in children with dysfunctional voiding | 2010 | n=8643 control43 experimental | Diaphragmatic breathing and pelvic floor muscle training. |

| 3 | Transcutaneous interferential electrical stimulation for the management of non-neuropathic underactive bladder in children: A randomized clinical trial | 2016 | n=3618 control18 experimental | Transcutaneous interferential electrical stimulation. |

| 4 | Management of non-neuropathic underactive bladder in children with voiding dysfunction by animated biofeedback: a randomized clinical trial | 2015 | n=5025 control25 experimental | Animated biofeedback. |

| 5 | Bladder training video versus standard urotherapy for bladder and bowel dysfunction: a non-inferiority randomized, controlled trial | 2017 | n=15075 control75 experimental | Video animation. |

| 6 | The impact of a bladder training video versus standard urotherapy on quality of life of children with bladder and bowel dysfunction: A randomized controlled trial | 2017 | n=15075 control75 experimental | Video animation. |

| 7 | Parasacral transcutaneous electrical neural stimulation (PTENS) once a week for the treatment of overactive bladder in children: A randomized controlled trial | 2017 | n=168 control8 experimental | Parasacral transcutaneous electrical stimulation. |

| 8 | Are interferential electrical stimulation and diaphragmatic breathing exercises beneficial in children with bladder and bowel dysfunction? | 2017 | n=7924 control25 control+breathing30 experimental | Interferential electrical stimulation diaphragmatic breathing. |

| 9 | Efficacy of combined anticholinergic treatment and behavioral modification as a first line treatment for non-neurogenic and non-anatomical voiding dysfunction in children: a randomized controlled trial | 2007 | n=7220 control20 control+placebo32 experimental | Tolterodine (anticholinergic). |

| 10 | A pilot randomized controlled trial evaluating the effectiveness of group vs. individual urotherapy in decreasing symptoms associated with bladder-bowel dysfunction | 2015 | n=6030 control30 experimental | Group urotherapy guidelines. |

| 11 | Animated biofeedback: An ideal treatment for children with dysfunctional elimination syndrome | 2011 | n=8040 control40 experimental | Animated biofeedback. |

| 12 | Two sessions of behavioral urotherapy for bowel and bladder dysfunction: does it get any better? | 2014 | n=368No control group – effectiveness evaluation by number of consultations | Does not apply. |

| 13 | Combined functional pelvic floor muscle exercises with Swiss ball and urotherapy for management of dysfunctional voiding in children: a randomized clinical trial | 2014 | n=6030 control30 experimental | Pelvic floor exercises.Swiss ball. |

| 14 | Long-term prospective evaluation of an inpatient voiding reeducation program for lower urinary tract conditions in children | 2013 | n=6432 control32 experimental | Urotherapy started three months after diagnosis |

The articles comparing standard urotherapy with standard urotherapy plus specific urotherapy or anticholinergic therapy, showed better results for the groups that received the two associated therapies. On the other hand, articles comparing alternative forms of urotherapy protocol (presentation of animated video content and group approach) did not show better results for the tested modalities when compared to the traditional ones.

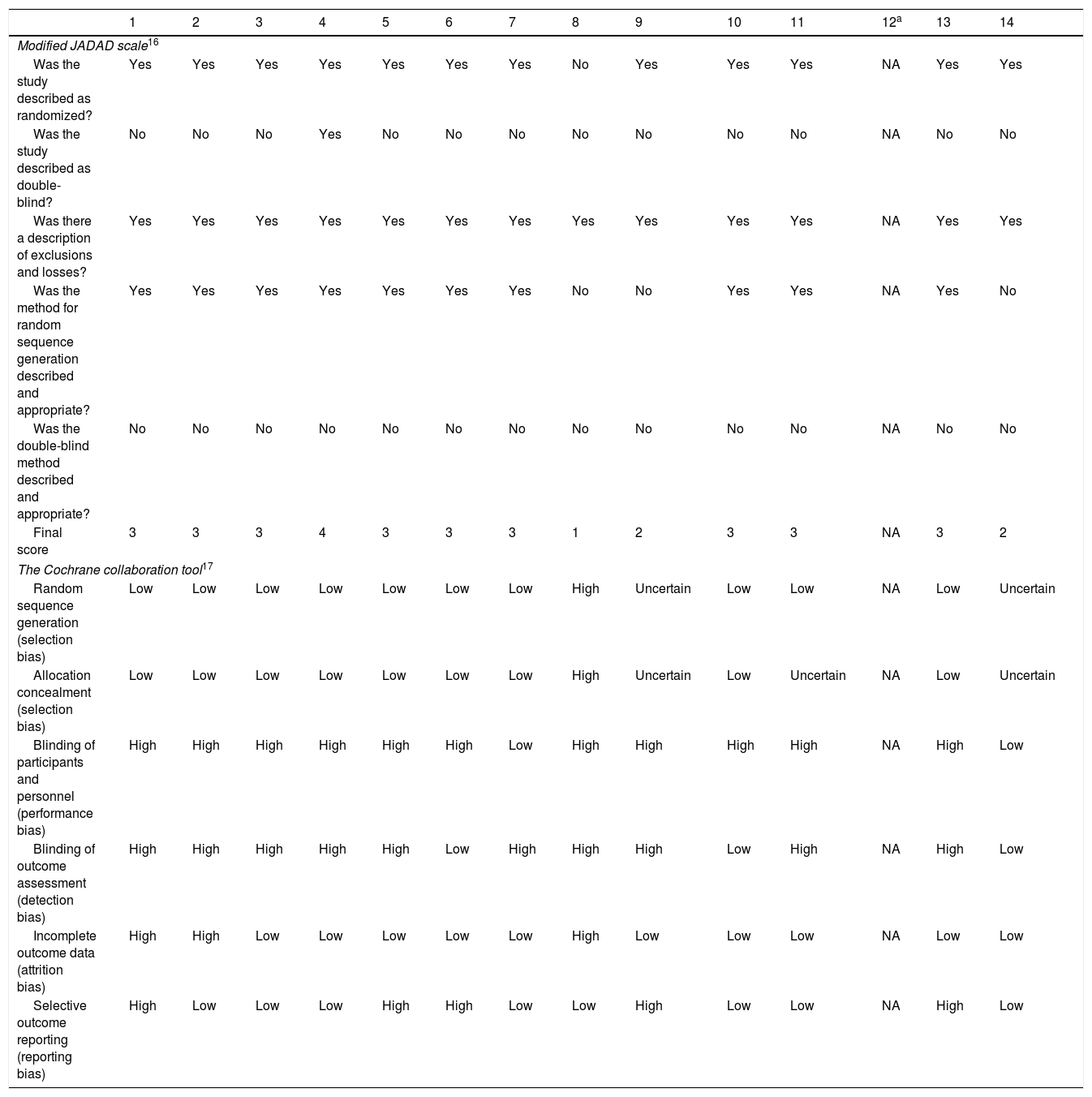

Regarding the study quality and risk of bias, Table 3 shows the classification discriminating each item evaluated, through the two adopted tools.

Article classification regarding quality and risk of bias, according to the modified Jadad tool and the Cochrane Tool. Brasília, Brazil, 2019.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12a | 13 | 14 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modified JADAD scale16 | ||||||||||||||

| Was the study described as randomized? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | Yes |

| Was the study described as double-blind? | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | NA | No | No |

| Was there a description of exclusions and losses? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | Yes |

| Was the method for random sequence generation described and appropriate? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | No |

| Was the double-blind method described and appropriate? | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | NA | No | No |

| Final score | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | NA | 3 | 2 |

| The Cochrane collaboration tool17 | ||||||||||||||

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | High | Uncertain | Low | Low | NA | Low | Uncertain |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | High | Uncertain | Low | Uncertain | NA | Low | Uncertain |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High | High | High | High | High | High | Low | High | High | High | High | NA | High | Low |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | High | High | High | High | High | Low | High | High | High | Low | High | NA | High | Low |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High | High | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | High | Low | Low | Low | NA | Low | Low |

| Selective outcome reporting (reporting bias) | High | Low | Low | Low | High | High | Low | Low | High | Low | Low | NA | High | Low |

NA, not applicable; Low, low risk of bias; High, high risk of bias; Uncertain, uncertain risk of bias due to lack of information in the study.

It can be observed that most of the studies scored 3 on the Jadad scale, showing moderate methodological quality. Similarly, regarding the bias analysis by the Cochrane Collaboration Tool, most studies showed a high risk for performance and detection bias. The two tools showed this limitation of the studies is directly associated with the non-blinding of the participants, personnel, and outcome evaluators. Only the authors of one article defined it as a double-blind trial, but they did not provide the description of the blinding procedures and the type of intervention applied, which makes the blinding process a questionable one.

Studies 8, 9, and 14 were those that scored below 3, therefore being rated as low quality. Study 8 was not classified as randomized, and the allocation of the participants was quite biased, since studies 9 and 14 did not appropriately describe the randomization method.

As for the Cochrane tool, the weak items of most studies were related to the performance and detection biases, as they were not double-blind studies. Article 14 showed low risk in these two types of bias because, although there was no blinding, it was considered as not interfering in the analysis of the results (since both groups were submitted to standard urotherapy). Studies 6 and 10 blinded only the outcome evaluators and article 7 managed to blind the participants.

As for the attrition bias, the studies that received high-risk classification were those that showed participant withdrawal in the control group disproportionally to the experimental group (1, 2, and 8). As for the reporting bias, the studies that received high-risk classification were the ones that did not show the results of all the variables mentioned in the method (1, 5, 6, 9, and 13).

Although all studies consisted of a sample of children and/or adolescents with BBD (with at least one urinary and one intestinal symptom), some of them were about specific dysfunctions, such as detrusor underactivity or overactivity. Therefore, the signs and symptoms of BBD analyzed between the studies were not homogeneous. Hence, the analysis and comparison of the outcomes of urotherapy programs between the studies depended on the description of the symptoms and the similarities between them.

Articles 5, 6, 8, 10, 12, and 14 included patients with general BBD symptoms, whereas articles 1, 2, 9, 11, and 13 limited the sample to children and/or adolescents with dysfunctional urination, characterized by pelvic contraction during the bladder emptying phase. Articles 3 and 4 analyzed patients with non-neuropathic detrusor underactivity and article 7, with detrusor overactivity.

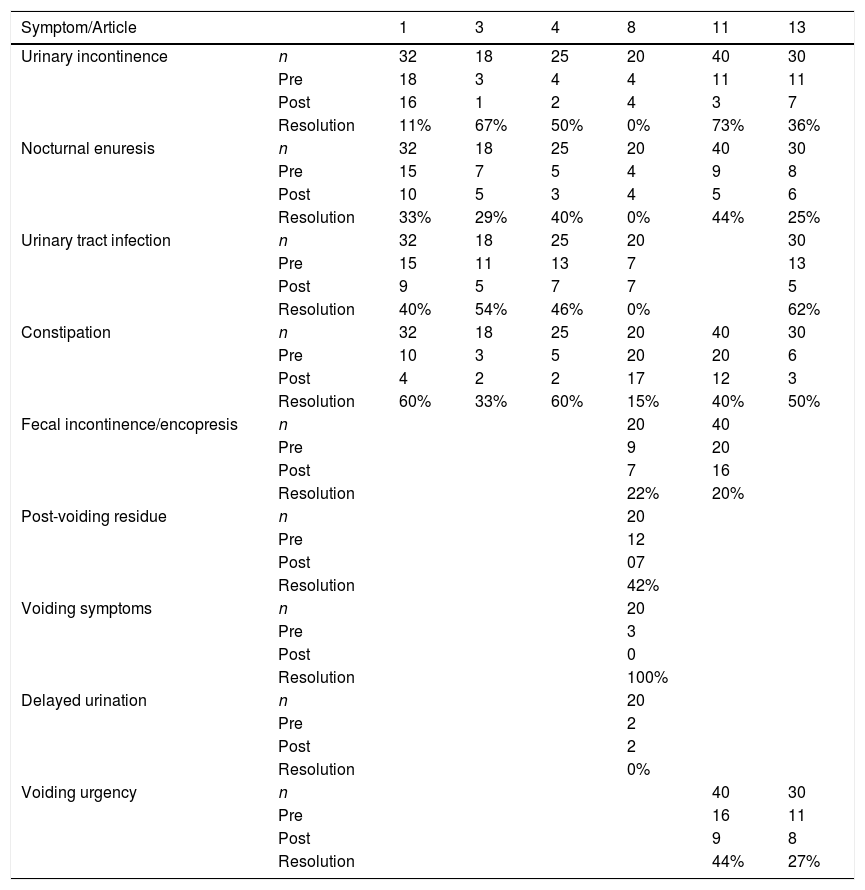

Table 4 shows the symptoms analyzed in the studies before and after urotherapy application. Not all publications showed the outcomes of symptom treatments, thus not all of them were shown in Table 4. Moreover, not all symptoms were analyzed for all assessed studies, which depended on the sample profile and the study aim.

Comparison of symptoms before and after protocol application. Urotherapy in the treatment of children and adolescents with bladder and bowel dysfunction: a systematic review. Brasília, Brazil, 2019.

| Symptom/Article | 1 | 3 | 4 | 8 | 11 | 13 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urinary incontinence | n | 32 | 18 | 25 | 20 | 40 | 30 |

| Pre | 18 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 11 | 11 | |

| Post | 16 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 7 | |

| Resolution | 11% | 67% | 50% | 0% | 73% | 36% | |

| Nocturnal enuresis | n | 32 | 18 | 25 | 20 | 40 | 30 |

| Pre | 15 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 9 | 8 | |

| Post | 10 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| Resolution | 33% | 29% | 40% | 0% | 44% | 25% | |

| Urinary tract infection | n | 32 | 18 | 25 | 20 | 30 | |

| Pre | 15 | 11 | 13 | 7 | 13 | ||

| Post | 9 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 5 | ||

| Resolution | 40% | 54% | 46% | 0% | 62% | ||

| Constipation | n | 32 | 18 | 25 | 20 | 40 | 30 |

| Pre | 10 | 3 | 5 | 20 | 20 | 6 | |

| Post | 4 | 2 | 2 | 17 | 12 | 3 | |

| Resolution | 60% | 33% | 60% | 15% | 40% | 50% | |

| Fecal incontinence/encopresis | n | 20 | 40 | ||||

| Pre | 9 | 20 | |||||

| Post | 7 | 16 | |||||

| Resolution | 22% | 20% | |||||

| Post-voiding residue | n | 20 | |||||

| Pre | 12 | ||||||

| Post | 07 | ||||||

| Resolution | 42% | ||||||

| Voiding symptoms | n | 20 | |||||

| Pre | 3 | ||||||

| Post | 0 | ||||||

| Resolution | 100% | ||||||

| Delayed urination | n | 20 | |||||

| Pre | 2 | ||||||

| Post | 2 | ||||||

| Resolution | 0% | ||||||

| Voiding urgency | n | 40 | 30 | ||||

| Pre | 16 | 11 | |||||

| Post | 9 | 8 | |||||

| Resolution | 44% | 27% |

n, total number of children/adolescents submitted to isolated urotherapy, it does not represent the total number of the study sample, consisting of control group (urotherapy) and experimental group (adjuvant therapy); Pre, number of children/adolescents who had the symptom before the urotherapy; Post, number of children/adolescents who remained with the symptom after treatment with urotherapy.

The mean percentage of assessed symptom resolution using standard urotherapy was 39.5% for urinary incontinence, 28.5% for nocturnal enuresis, 43% for constipation (analyzed by six of the 14 articles), 40.4% for urinary tract infection, analyzed in five articles, 21% for fecal incontinence, and 35.5% for urinary urgency, analyzed in two articles. It was not possible to calculate the mean resolution for increased post-voiding residue, voiding symptoms, and delayed urination, as they were analyzed in only one article.

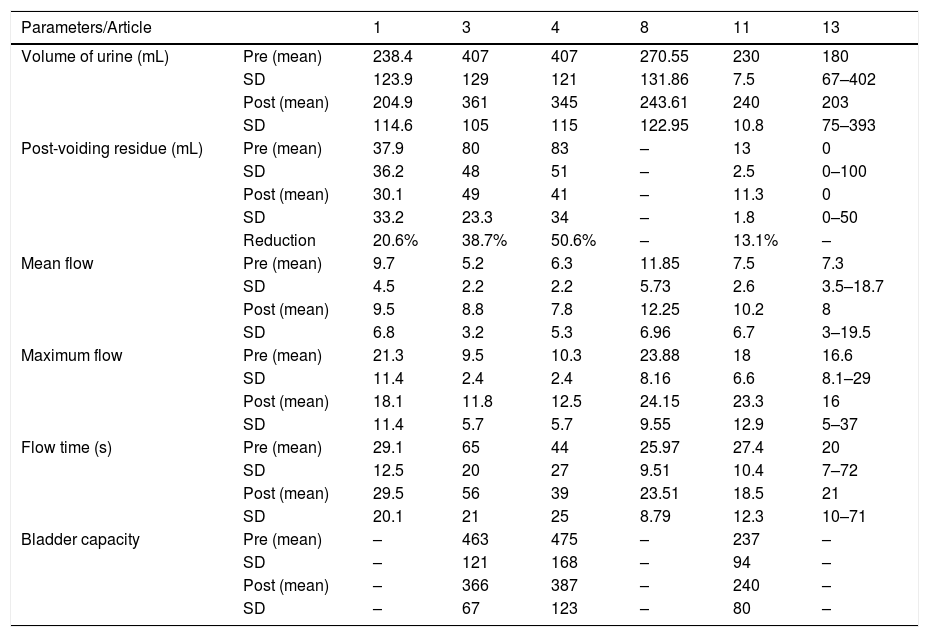

Table 5 shows the uroflowmetry parameters analyzed in the studies, before and after urotherapy application. Not all articles analyzed uroflowmetry parameters and not all that used these data showed all the parameters of the exam.

Uroflowmetry parameters before and after protocol application. Urotherapy in the treatment of children and adolescents with bladder and bowel dysfunction: a systematic review. Brasília, Brazil, 2019.

| Parameters/Article | 1 | 3 | 4 | 8 | 11 | 13 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Volume of urine (mL) | Pre (mean) | 238.4 | 407 | 407 | 270.55 | 230 | 180 |

| SD | 123.9 | 129 | 121 | 131.86 | 7.5 | 67–402 | |

| Post (mean) | 204.9 | 361 | 345 | 243.61 | 240 | 203 | |

| SD | 114.6 | 105 | 115 | 122.95 | 10.8 | 75–393 | |

| Post-voiding residue (mL) | Pre (mean) | 37.9 | 80 | 83 | – | 13 | 0 |

| SD | 36.2 | 48 | 51 | – | 2.5 | 0–100 | |

| Post (mean) | 30.1 | 49 | 41 | – | 11.3 | 0 | |

| SD | 33.2 | 23.3 | 34 | – | 1.8 | 0–50 | |

| Reduction | 20.6% | 38.7% | 50.6% | – | 13.1% | – | |

| Mean flow | Pre (mean) | 9.7 | 5.2 | 6.3 | 11.85 | 7.5 | 7.3 |

| SD | 4.5 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 5.73 | 2.6 | 3.5–18.7 | |

| Post (mean) | 9.5 | 8.8 | 7.8 | 12.25 | 10.2 | 8 | |

| SD | 6.8 | 3.2 | 5.3 | 6.96 | 6.7 | 3–19.5 | |

| Maximum flow | Pre (mean) | 21.3 | 9.5 | 10.3 | 23.88 | 18 | 16.6 |

| SD | 11.4 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 8.16 | 6.6 | 8.1–29 | |

| Post (mean) | 18.1 | 11.8 | 12.5 | 24.15 | 23.3 | 16 | |

| SD | 11.4 | 5.7 | 5.7 | 9.55 | 12.9 | 5–37 | |

| Flow time (s) | Pre (mean) | 29.1 | 65 | 44 | 25.97 | 27.4 | 20 |

| SD | 12.5 | 20 | 27 | 9.51 | 10.4 | 7–72 | |

| Post (mean) | 29.5 | 56 | 39 | 23.51 | 18.5 | 21 | |

| SD | 20.1 | 21 | 25 | 8.79 | 12.3 | 10–71 | |

| Bladder capacity | Pre (mean) | – | 463 | 475 | – | 237 | – |

| SD | – | 121 | 168 | – | 94 | – | |

| Post (mean) | – | 366 | 387 | – | 240 | – | |

| SD | – | 67 | 123 | – | 80 | – |

Pre, mean value of the parameter before therapy; Post, mean value of the parameter after the children/adolescents were submitted to the program.

As previously mentioned, studies 1, 8, 11, and 13 consisted of a sample of children with dysfunctional voiding, i.e., who maintained the pelvic floor contracted during urination, who had difficulties for total volume voiding. In these cases, an adequate response to the treatment would be the increase in urinary volume, which occurred in studies 11 and 13.

Studies 3 and 4 consisted of a sample of children with a diagnosis of detrusor underactivity, that is, with bladder sensitivity reduction, high bladder capacity, emptying contraction with reduced force and duration, long urination, and need for abdominal pressure. In such cases, an adequate response to treatment would be a decrease in urinary volume and bladder capacity, which were successful in both studies.

All studies that analyzed post-voiding residue were successful, with volume reduction at the end of the treatment. In particular, studies 3 and 4 (children with detrusor underactivity) were able to reduce the residual volume by almost half.

Articles 3, 4, 8, and 11 showed an improvement in the flow time parameter, demonstrating improvement of the condition. No significant differences were identified in the maximum and mean flow parameters in the studies that analyzed this variable.

In addition to the results of urotherapy effectiveness, a descriptive analysis of the protocol applied in each study was performed. Many of the analyzed studies did not show the protocol in terms of number of consultations, time of consultation and interval between them, not allowing a detailed synthesis of this information. Only study 10 reported that the individual urotherapy consultation (control group) lasted 15min, study 11 mentioned a one-month interval between consultations, and study 14 reported that the guidance session lasted 60min, with a maximum number of six consultations.

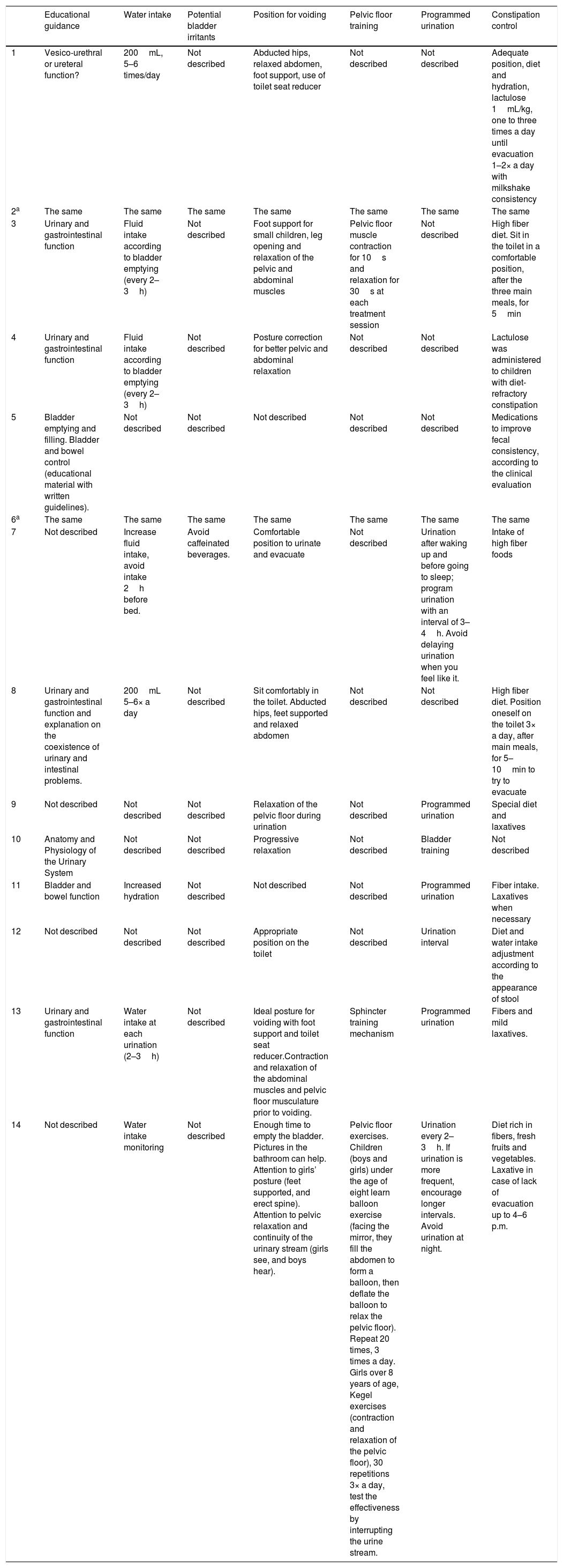

Table 6 summarizes the information regarding the urotherapy components applied in each study. It can be observed that none of the articles covers the application of all components described in the International Children's Continence Society (ICCS) recommendations.1

Urotherapy components applied by the studies included in the review: Urotherapy in pediatric bladder and bowel dysfunction: a systematic review. Brasília, Brazil, 2019.

| Educational guidance | Water intake | Potential bladder irritants | Position for voiding | Pelvic floor training | Programmed urination | Constipation control | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Vesico-urethral or ureteral function? | 200mL, 5–6 times/day | Not described | Abducted hips, relaxed abdomen, foot support, use of toilet seat reducer | Not described | Not described | Adequate position, diet and hydration, lactulose 1mL/kg, one to three times a day until evacuation 1–2× a day with milkshake consistency |

| 2a | The same | The same | The same | The same | The same | The same | The same |

| 3 | Urinary and gastrointestinal function | Fluid intake according to bladder emptying (every 2–3h) | Not described | Foot support for small children, leg opening and relaxation of the pelvic and abdominal muscles | Pelvic floor muscle contraction for 10s and relaxation for 30s at each treatment session | Not described | High fiber diet. Sit in the toilet in a comfortable position, after the three main meals, for 5min |

| 4 | Urinary and gastrointestinal function | Fluid intake according to bladder emptying (every 2–3h) | Not described | Posture correction for better pelvic and abdominal relaxation | Not described | Not described | Lactulose was administered to children with diet-refractory constipation |

| 5 | Bladder emptying and filling. Bladder and bowel control (educational material with written guidelines). | Not described | Not described | Not described | Not described | Not described | Medications to improve fecal consistency, according to the clinical evaluation |

| 6a | The same | The same | The same | The same | The same | The same | The same |

| 7 | Not described | Increase fluid intake, avoid intake 2h before bed. | Avoid caffeinated beverages. | Comfortable position to urinate and evacuate | Not described | Urination after waking up and before going to sleep; program urination with an interval of 3–4h. Avoid delaying urination when you feel like it. | Intake of high fiber foods |

| 8 | Urinary and gastrointestinal function and explanation on the coexistence of urinary and intestinal problems. | 200mL 5–6× a day | Not described | Sit comfortably in the toilet. Abducted hips, feet supported and relaxed abdomen | Not described | Not described | High fiber diet. Position oneself on the toilet 3× a day, after main meals, for 5–10min to try to evacuate |

| 9 | Not described | Not described | Not described | Relaxation of the pelvic floor during urination | Not described | Programmed urination | Special diet and laxatives |

| 10 | Anatomy and Physiology of the Urinary System | Not described | Not described | Progressive relaxation | Not described | Bladder training | Not described |

| 11 | Bladder and bowel function | Increased hydration | Not described | Not described | Not described | Programmed urination | Fiber intake. Laxatives when necessary |

| 12 | Not described | Not described | Not described | Appropriate position on the toilet | Not described | Urination interval | Diet and water intake adjustment according to the appearance of stool |

| 13 | Urinary and gastrointestinal function | Water intake at each urination (2–3h) | Not described | Ideal posture for voiding with foot support and toilet seat reducer.Contraction and relaxation of the abdominal muscles and pelvic floor musculature prior to voiding. | Sphincter training mechanism | Programmed urination | Fibers and mild laxatives. |

| 14 | Not described | Water intake monitoring | Not described | Enough time to empty the bladder. Pictures in the bathroom can help. Attention to girls’ posture (feet supported, and erect spine). Attention to pelvic relaxation and continuity of the urinary stream (girls see, and boys hear). | Pelvic floor exercises. Children (boys and girls) under the age of eight learn balloon exercise (facing the mirror, they fill the abdomen to form a balloon, then deflate the balloon to relax the pelvic floor). Repeat 20 times, 3 times a day. Girls over 8 years of age, Kegel exercises (contraction and relaxation of the pelvic floor), 30 repetitions 3× a day, test the effectiveness by interrupting the urine stream. | Urination every 2–3h. If urination is more frequent, encourage longer intervals. Avoid urination at night. | Diet rich in fibers, fresh fruits and vegetables. Laxative in case of lack of evacuation up to 4–6 p.m. |

Regarding specifically the urotherapy components, the first item presented was educational guidance. Four studies did not mention this component, and all that mentioned it somehow addressed the urinary function, whereas five added bowel function and one addressed problems present in those systems.

Nine studies addressed the fluid intake component, six added the indicated volume or frequency of intake, which was presented as “one glass every two to three hours” or “200mL five to six times a day.” Only one article adopted the potential bladder-irritating foods item, recommending the reduction of caffeinated beverages.

Eleven articles mention the positioning on the toilet as part of the urotherapy program. The supporting of the feet on a stand appears in six articles, whereas relaxation while sitting on the toilet is mentioned in seven studies. Strategies for relaxation comprised breathing techniques, pelvic floor training, programmed time for voiding and, pictures in the bathroom, for diversion. Abduction of the hips, an upright spine, use of a toilet seat reducer, and observation of the urinary stream continuity also appear in the “posture” item.

The pelvic floor muscle training appears as the standard urotherapy program in three studies. It is worth mentioning that this component is considered as “specific urotherapy” in the ICCS documents. Thus, in some studies, the pelvic floor muscle training appears as an experimental group, in comparison with the standard urotherapy of the control group, and in these cases the results are not depicted in the table that summarizes the components applied by the authors as standard urotherapy.

Seven studies used the programmed urination component, and the frequently targeted urination interval was between 2–3h, with discontinuation of this interval during the night. The intestinal constipation control item was the one most often addressed by the authors in the urotherapy protocol application, mentioned in all 14 articles. A high-fiber diet was the most frequently observed item, followed by the use of laxatives. The laxative mentioned by the studies was lactulose, used in case of failure with diet adjustment or absence of evacuation until the end of the afternoon. Two articles describe the bowel movement-conditioning, suggesting positioning oneself on the toilet for 5min, three times a day, after the main meals.

DiscussionStandard urotherapy was predominantly applied to the control groups, in order to compare it with its application plus components of specific urotherapy, anticholinergic drugs, or alternative ways of recommending the program components. This result shows that standard urotherapy is the group of behavioral measures considered as the recommended approach in the first-line treatment to control the symptoms of BBD in children and adolescents, which makes it even more necessary to understand its components and application modalities.

According to the ICCS recommendations, all children with diurnal urinary incontinence should receive standard urotherapy as the first line of treatment and only those with a refractory condition should be submitted to further investigation and application of specific urotherapy components.7 It is worth mentioning that the application of standard urotherapy as a first line of treatment reduces the costs for health services and responsible for the child/adolescent, since it does not depend on specific equipment and materials but on the professional's educational abilities.

The percentage calculation showed a reduction in the number of children/adolescents who had the symptoms analyzed after the standard urotherapy was applied. This result was also described in other studies, but in cases of LUTS. A meta-analysis that assessed the effectiveness of urotherapy compared with spontaneous remission of diurnal urinary incontinence showed that standard urotherapy is an effective cognitive-behavioral intervention in the treatment of children and adolescents with this symptom.31 A European study showed a symptom reduction of approximately 40% in children with diurnal urinary incontinence, only with the application of standard urotherapy.32

The observed result, which showed that groups receiving standard urotherapy plus components of specific urotherapy or drug therapy had a higher rate of symptom reduction, was expected. This is due to the fact that the experimental group received the tested therapy as an addition to the standard urotherapy, rather than a replacement to it. Previous studies have described similar results with the use of biofeedback in children with dysfunctional voiding.33

Regarding the articles that compared alternative forms of urotherapy protocol application (video animation and group application), which did not show better results for the tested modalities, similar results were observed by authors that compared standard urotherapy application by using games. The children did not differ regarding motivation and the training results were the same in both groups, with 80% resolved or improved symptoms.34 These results reinforce the applicability and effectiveness of the standard approach in which the professional welcomes, evaluates, and assesses the child/adolescent using an individualized approach.

The descriptive analysis of the uroflowmetry parameters shows the improvement of parameters with the standard urotherapy application. Other authors have previously demonstrated the uroflowmetry curve normalization, reduction of bladder capacity (initially increased), and post-voiding residue, through water intake encouragement and voiding interval control,35 two components applied by most studies of this systematic review.

When further analyzing the question of the components applied by the authors in standard urotherapy, the identified components meet the ICCS recommendations,1 as in the case of the aforementioned fluid intake and voiding interval. However, the authors did not apply the complete set of recommendations found in that document. Considering an overview of the articles, the applied components were: educational guidance, with greater focus on bladder and bowel function; bowel function control, especially by recommending a high-fiber diet and use of laxatives, when diet adequacy does not show satisfactory results; positioning on the toilet, with relaxation of the pelvic muscles, which can be promoted by foot support on a stand, use of a seat reducer (when necessary) and diaphragmatic breathing exercises; water intake, one glass every 2–3h (five to six times a day) and programmed urination, every 2–3h during the day.

The intestinal constipation control was the most often discussed component by the authors in their urotherapy programs. In BBD, it is evident that the intestinal approach is necessary, since the patients have evacuation alterations. However, it is known that the intestinal function control has a positive effect also on the reduction of urinary symptoms. A study showed good results when using enemas as an early part of the treatment in children with LUTS. The author defends that voiding problems can begin with a painful evacuation, leading to stool retention, rectal dilatation, dysfunctional rectum and, simultaneously, an exacerbated and reflexively contracted pelvic floor, resulting in dysfunctional voiding.36 Therefore, when treatment aims at bowel function improvement, the child would show a reduction in pelvic muscle tension and, consequently, a better pattern of bladder emptying.

Mentioning a neglected component in the studies, caffeine reduction was addressed by only one article included in the review, although included in the ICCS consensus.1 It is known that caffeine is a potential bladder irritant and that its consumption reduction can control irritative symptoms, such as urgency. It is possible that professionals do not prioritize this recommendation in urotherapy programs applied to children by associating caffeine with coffee, a beverage not commonly consumed by children. However, it is worth remembering that in addition to coffee, other beverages are potential bladder irritants, such as carbonated or artificially-flavored drinks.37 The fact that this urotherapy component is neglected in the analyzed studies deserves to be highlighted and indicates the need for studies investigating its action on BBD symptom reduction in the pediatric context.

Few studies showed information on the duration, frequency, or number of consultations for the urotherapy program. Based on the studies that provided these data, it is possible to suggest that at least two consultations occur with an individual approach, lasting between 15 and 60min. Not even consensuses1 and reviews2 about urotherapy show data related to such information, as all address the components of a program, but given the amount of suggested information, it is unlikely that the child/adolescent will be able to absorb, assimilate, and adhere to all expected behavioral measures with a single consultation or session. Thus, the question regarding how many consultations, their duration and frequency, and what information should be addressed in each of them remains unanswered.

Finally, the professional's role in the context of primary care is emphasized. The application of urotherapy by such a professional would reduce waiting for specialized services, optimizing care for complex or refractory cases.

As for implications to future studies, the present authors suggest carrying out controlled and randomized clinical trials comparing different urotherapy protocol components or modalities, regarding duration, frequency, and number of consultations, as well as the content to be addressed in each consultation.

LimitationsA study limitation was the methodological heterogeneity of the studies, which prevented the sample summation for complex statistical analysis, such as meta-analysis in the evaluation of symptom alteration with the isolated urotherapy application. Other limitations were related to the parameters of uroflowmetry; in addition to the lack of a comparative statistical analysis between before and after the application of standard urotherapy, the analyzed groups were distinct regarding the diagnosis. Thus, the expected result diverged, making it difficult to perform a numerical analysis that contemplated all the studies that analyzed these parameters. For instance, for samples with detrusor overactivity, an increase in urine volume was expected; on the other hand, in cases of detrusor underactivity, a reduction in volume would demonstrate improvement of the clinical outcome.

Overall, the studies were well described methodologically, but the quality assessment of the clinical trials showed a moderate quality and bias risk due to the lack of study blinding. It is worth mentioning the difficulty in performing a double-blind study for the proposed intervention, since both urotherapy and adjuvant therapies are clearly identified by the one applying the therapy or the participant. Nonetheless, it would have been possible in isolated cases (medication and electrostimulation) and it would have been possible to blind the evaluator of the results in all studies, which was observed only in three of them.

ConclusionThis systematic review shows positive outcomes in terms of symptom reduction and improvement in uroflowmetry parameters when the standard urotherapy was applied as the first-line treatment in cases of BBD in children and adolescents. The studies were weak regarding the detailed description of the components and the description of how the protocol was applied, not allowing us to infer regarding the frequency, number, and duration of urotherapy consultations.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Assis GM, Silva CP, Martins G. Urotherapy in the treatment of children and adolescents with bladder and bowel dysfunction: a systematic review. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2019;95:628–41.