To evaluate the role of echocardiography in reducing shock reversal time in pediatric septic shock.

MethodsA prospective study conducted in the pediatric intensive care unit of a tertiary care teaching hospital from September 2013 to May 2016. Ninety septic shock patients were randomized in a 1:1 ratio for comparing the serial echocardiography-guided therapy in the study group with the standard therapy in the control group regarding clinical course, timely treatment, and outcomes.

ResultsShock reversal was significantly higher in the study group (89% vs. 67%), with significantly reduced shock reversal time (3.3 vs. 4.5 days). Pediatric intensive care unit stay in the study group was significantly shorter (8±3 vs. 14±10 days). Mortality due to unresolved shock was significantly lower in the study group. Fluid overload was significantly lower in the study group (11% vs. 44%). In the study group, inotropes were used more frequently (89% vs. 67%) and initiated earlier (12[0.5–24] vs. 24[6–72]h) with lower maximum vasopressor inotrope score (120[30–325] vs. 170[80–395]), revealing predominant use of milrinone (62% vs. 22%).

ConclusionSerial echocardiography provided crucial data for early recognition of septic myocardial dysfunction and hypovolemia that was not apparent on clinical assessment, allowing a timely management and resulting in shock reversal time reduction among children with septic shock.

Avaliar o papel da ecocardiografia na redução do tempo de reversão do choque no choque séptico pediátrico.

MétodosUm estudo prospectivo conduzido em uma UTIP de um hospital universitário de cuidados terciários de setembro de 2013 a maio de 2016. 90 pacientes com choque séptico foram randomizados na proporção 1:1 para comparar a terapia guiada por ecocardiografia em série à terapia padrão no grupo de controle com relação ao curso clínico, tratamento oportuno e resultados.

ResultadosA reversão do choque foi significativamente maior no grupo de estudo (89% em comparação a 67%) com redução significativa do tempo de reversão do choque (3,3 em comparação a 4,5 dias). A permanência na UTIP no grupo de estudo foi significativamente mais curta (8±3 em comparação a 14±10 dias). A mortalidade devido ao choque não resolvido foi significativamente menor no grupo de estudo. A sobrecarga de fluidos foi significativamente menor no grupo de estudo (11% em comparação a 44%). No grupo de estudo, os inotrópicos foram utilizados com mais frequência (89% em comparação a 67%) e foram administrados antecipadamente (12 [0,5-24] em comparação a 24 [6-72] horas), e o menor escore inotrópico máximo dos vasopressores (120 [30-325] em comparação a 170 [80-395]) revela o uso predominante de milrinona (62% em comparação a 22%).

ConclusãoA ecocardiografia em série forneceu dados fundamentais para o reconhecimento precoce da disfunção miocárdica séptica e hipovolemia não evidente na avaliação clínica, possibilitando o manejo tempestivamente adequado e resultando na redução do tempo de reversão do choque entre crianças com choque séptico.

Sepsis is the leading cause of death worldwide in the pediatric population, resulting in an estimated 7.5 million deaths annually.1,2 Globally, point prevalence of severe sepsis among pediatric intensive care units (PICUs) is 8.2%, ranging from 6.2% in developed countries to 23% in developing countries.3

Despite advances in understanding the pathophysiology of septic shock, mortality due to septic shock in children is still high, reaching 10–13% in developed countries, 18–24% in resource-restricted countries; in few other countries, this rate reaches 34–58%.3,4

Based on the International Pediatric Sepsis Consensus, septic shock is defined as sepsis with cardiovascular organ dysfunction.5,6 Circulatory instability and myocardial dysfunction are the leading causes of death.7 During treatment, physical examination may not be sensitive enough to detect early and subtle changes in pathophysiology that can have important implications for treatment and outcomes. Inadequate/inappropriate or delayed onset of supportive care may worsen outcomes. Bedside echocardiography overcomes this problem by allowing direct visualization of the heart and great veins to optimize therapy.8,9 However, reports of the use of echocardiography in pediatric septic shock are limited.

The latest international management guidelines included fluid resuscitation in bolus over 5–10min, titrated to reverse hypotension, increase urine output, and attain normal capillary refill, peripheral pulses, and level of consciousness without inducing hepatomegaly or rales. In cases of hepatomegaly or rales development, inotropic support should be implemented.6,10

Some investigators believe that the current pediatric guidelines are still preliminary and require review by large multi-institutional prospective studies.1 The present study aimed to assess the use of echocardiography in the reduction of shock reversal time in pediatric septic shock by optimizing fluid and vasoactive/inotropic therapy. The study aims to provide useful data to be incorporated in future pediatric sepsis guidelines.

MethodsThis prospective randomized clinical study was conducted in the PICU of Alexandria University Teaching Hospital, from September 2013 to May 2016. The study was approved by the ethical committee of Alexandria University, and informed consent was obtained from the patients’ parents.

Eligibility criteriaConsecutive patients aged 1 month to 11 years were eligible if they had a new episode of septic shock upon admission to the PICU. Pediatric septic shock was defined based on the American College of Critical Care Medicine and International Pediatric Sepsis Consensus.5,6

Exclusion criteriaPatients with myocarditis, cardiomyopathy, cardiothoracic surgery, and congenital heart disease were excluded, as well as those on vasopressors/inotropes before PICU admission.

Study protocolReduction of shock reversal time was the primary goal. A sample size of 70 was calculated to estimate a clinically significant difference in shock reversal time between the two groups of 51.7±15.6min, using alpha error of 0.05 and 10% of precision rate to provide a study power of 80%.11 The calculated difference was obtained from a prior pilot study, due to lack of similar study designs. Block randomization was done using a web-based software, to assign 90 patients in a 1:1 ratio to either the control group, in which septic shock was managed in adherence with current pediatric sepsis guidelines as detailed in the pediatric section of Surviving Sepsis Campaign (SSC),10 or to the study group, in which septic shock was managed in accordance with the SSC guidelines, but was modified based on transthoracic echocardiography findings. Sequentially numbered sealed opaque closed envelopes were used by physicians to allocate eligible patients to either group.

For the study group, transthoracic echocardiography was performed by the corresponding author and all data were revised instantaneously by the second co-author, using Philips HD 11XE Doppler echocardiography system (model: Philips 989605325131, USA) at admission, 5, 10, 15, 20, 30min, and 1, 6, 24h from admission, and daily thereafter until the patient was discharged or deceased, aiming to assess two specific parameters: (a) volume status, (b) myocardial function. Volume status was assessed by inferior vena cava dimension (IVC) and respirophasic variation by comparing maximal diameters of the IVC in both phases of respiration in the anterior–posterior plane, just caudal to the hepatic vein confluence in the subxiphoid view, using 2-dimension (2D) and motion mode (M-mode).8,12 The maximal diameter of the IVC depended on the mode of ventilation during expiration in a spontaneously breathing (SB) patient (prior to intubation or after weaning from mechanical ventilation) and during inspiration on controlled mechanical ventilation (tidal volumes, 6–8mL/kg); SB was not permitted during echocardiography examination in ventilated patients.

A combination of two techniques was used to assess left ventricular (LV) systolic function. Qualitatively, LV function was evaluated by global visual assessment of LV contractility including assessment of motion and thickening of inter-ventricular septum and LV posterior wall in apical four chamber view; quantitatively, it was assessed by LV ejection fraction (EF) using M-mode in the parasternal long axis view.13 LV systolic function was categorized into three grades by a combination of visual assessment and measured LVEF. “Normal function” was defined as good contractility with LVEF of 56–78%; “dysfunction,” as decreased contractility with LVEF of less than 55%; and “hyperdynamic,” if the LV activity appeared vigorous with LVEF over 78%. LV diastolic function evaluated by transmitral pulsed wave Doppler focusing on the early (E wave) and the late (A wave) diastolic filling in apical four-chamber view and the ratio between them (E/A ratio).13 Diastolic dysfunction was considered when E/A ratio was less than 1. During the first hour, the authors relied on qualitative assessments of cardiac function; whenever cardiac abnormalities were detected, quantitative values were measured. All patients in the study group were qualitatively and quantitatively assessed at 1h and after that. Septic myocardial dysfunction (SMD) was considered present if the patient had LV systolic dysfunction, diastolic dysfunction, or both.

In the study group, therapy was adjusted according to the echocardiographic findings. Firstly, it guided fluid therapy; when IVC was collapsed or >50% respirophasic variation, fluid boluses were continued, and when IVC was normal or full with minimal respirophasic variation, fluid boluses were discontinued or decreased. Secondly, when SMD was present, inotropes were started. Dobutamine (up to 20μg/kg/min) and milrinone (0.25–0.75μg/kg/min) were used. When cardiac function was normalized, inotrope was continued at the same dose until the patient became hemodynamically stable. Inotropes were withdrawn in hyperdynamic cardiac function.

Data collectedData regarding the demographic characteristics, clinical features, clinical course, and investigations were recorded. Clinical evaluations on admission (Pediatric Index of Mortality 2 [PIM2] score)14 and clinical daily follow-up (Pediatric Logistic Organ Dysfunction [PELOD] score)15 were recorded. The following data were used for comparison between both groups initially and after 1, 6, and 24h: heart rate (HR), systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), mean arterial pressure (MAP), central venous pressure (CVP), perfusion pressure (MAP-CVP), central venous oxygen saturation (ScvO2), urine output, and arterial lactate level. Central venous catheters were inserted by the same team for both groups within the first hour of admission.

Therapeutic endpoints of resuscitation of septic shock were capillary refill of ≤2s; normal pulses with no differential between the quality of peripheral and central pulses; warm extremities; urine output >1mL/kg/h; normal mental status; normal HR, BP, and perfusion pressure for age; and ScvO2 saturation ≥70%.6,10

Treatment received was timely recorded. The vasoactive/inotrope score (VIS) was calculated daily.16 As soon as the therapeutic endpoints were achieved, vasopressors/inotropes were gradually weaned as patients tolerated. In cases of failure to maintain hemodynamic stability on the decreased doses, patients were returned to the last dose-maintaining stability. “Withdrawal time,” at which vasopressors/inotropes were initially successfully withdrawn, was recorded.

Outcomes“Shock reversal time” was recorded, defined as maintenance of SBP>5th centile for age or >70mmHg from 1 month-1year, (age×2+70) from 1 to 10 years, and SBP of at least 90mmHg in children >10 years; without vasopressor support for at least 24h.17

“Resuscitation time” was recorded when the patient met the therapeutic outcomes of septic shock resuscitation while on vasopressors/inotropes. The length of PICU stay among survivors and PICU mortality were also recorded.

Statistical analysisData were collected, revised, coded, and fed into statistical software SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0, NY, EUA).18 All statistical analysis was made using two-tailed tests. A significant statistical value of ≤0.05 was adopted. Descriptive statistics in the form of frequencies and percentages were used to describe the categorical data variables, while scale data were expressed by means and standard deviations for normally distributed variables, and as medians with ranges for skewed variables. To test for differences in percentages, exact tests were used while Mann–Whitney test and the t-test for independent samples were used for comparing median and means, respectively. Repeated measures ANOVA was used to compare means over time periods.

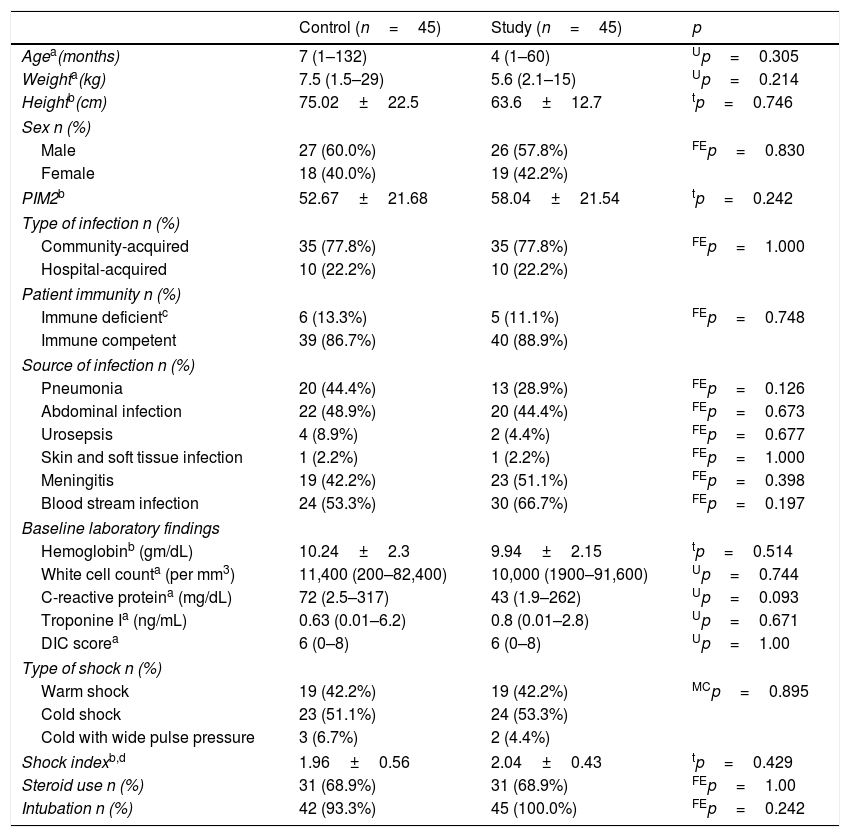

ResultsBaseline characteristics and initial assessmentAs shown in Table 1, there were no significant differences between the two groups regarding any of the baseline characteristics. Cold septic shock predominated in both groups.

Baseline characteristics and initial assessment.

| Control (n=45) | Study (n=45) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agea(months) | 7 (1–132) | 4 (1–60) | Up=0.305 |

| Weighta(kg) | 7.5 (1.5–29) | 5.6 (2.1–15) | Up=0.214 |

| Heightb(cm) | 75.02±22.5 | 63.6±12.7 | tp=0.746 |

| Sex n (%) | |||

| Male | 27 (60.0%) | 26 (57.8%) | FEp=0.830 |

| Female | 18 (40.0%) | 19 (42.2%) | |

| PIM2b | 52.67±21.68 | 58.04±21.54 | tp=0.242 |

| Type of infection n (%) | |||

| Community-acquired | 35 (77.8%) | 35 (77.8%) | FEp=1.000 |

| Hospital-acquired | 10 (22.2%) | 10 (22.2%) | |

| Patient immunity n (%) | |||

| Immune deficientc | 6 (13.3%) | 5 (11.1%) | FEp=0.748 |

| Immune competent | 39 (86.7%) | 40 (88.9%) | |

| Source of infection n (%) | |||

| Pneumonia | 20 (44.4%) | 13 (28.9%) | FEp=0.126 |

| Abdominal infection | 22 (48.9%) | 20 (44.4%) | FEp=0.673 |

| Urosepsis | 4 (8.9%) | 2 (4.4%) | FEp=0.677 |

| Skin and soft tissue infection | 1 (2.2%) | 1 (2.2%) | FEp=1.000 |

| Meningitis | 19 (42.2%) | 23 (51.1%) | FEp=0.398 |

| Blood stream infection | 24 (53.3%) | 30 (66.7%) | FEp=0.197 |

| Baseline laboratory findings | |||

| Hemoglobinb (gm/dL) | 10.24±2.3 | 9.94±2.15 | tp=0.514 |

| White cell counta (per mm3) | 11,400 (200–82,400) | 10,000 (1900–91,600) | Up=0.744 |

| C-reactive proteina (mg/dL) | 72 (2.5–317) | 43 (1.9–262) | Up=0.093 |

| Troponine Ia (ng/mL) | 0.63 (0.01–6.2) | 0.8 (0.01–2.8) | Up=0.671 |

| DIC scorea | 6 (0–8) | 6 (0–8) | Up=1.00 |

| Type of shock n (%) | |||

| Warm shock | 19 (42.2%) | 19 (42.2%) | MCp=0.895 |

| Cold shock | 23 (51.1%) | 24 (53.3%) | |

| Cold with wide pulse pressure | 3 (6.7%) | 2 (4.4%) | |

| Shock indexb,d | 1.96±0.56 | 2.04±0.43 | tp=0.429 |

| Steroid use n (%) | 31 (68.9%) | 31 (68.9%) | FEp=1.00 |

| Intubation n (%) | 42 (93.3%) | 45 (100.0%) | FEp=0.242 |

PIM2, Pediatric Index of Mortality2; DIC, disseminated intravascular coagulopathy; Up, p-value of Mann–Whitney test; tp, p-value of independent samples t-test; FEp, p-value of Fisher's exact probability test; MCp, p-value of the Mont Carlo's exact probability test.

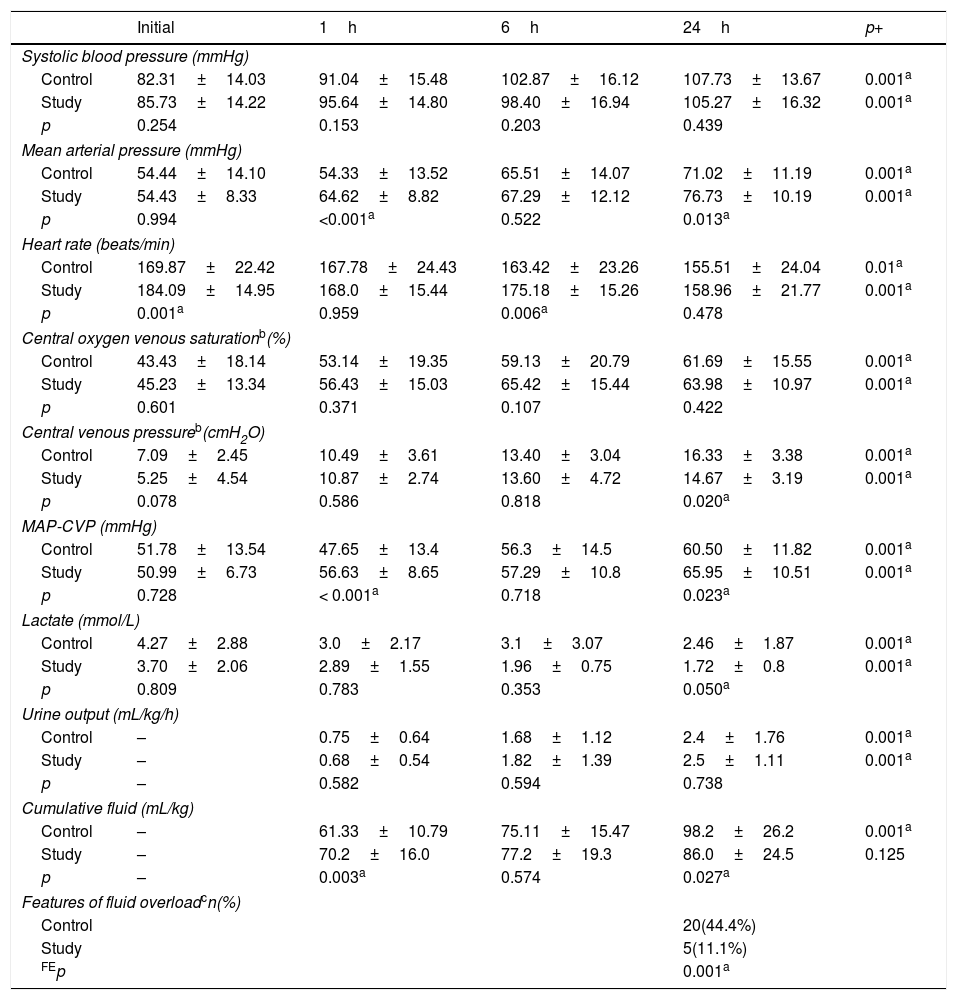

As shown in Table 2, there were no significant differences in the initial physiological variables, except for initial HR, which was higher in the study group. There was a significant improvement in all measured variables at the three-time points (1, 6, 24h) when compared with the initial values in both groups. MAP and MAP-CVP were significantly higher in the study group at 1 and 24h. At 24h, lactate values markedly improved in the study group to be less than 2mmol/L, while they failed to normalize in the control group. The patients in the study group received significantly more fluid in the first hour (70 vs. 61mL/kg; p=0.003); however, by the end of the 24h, the total fluid received was significantly lower (86 vs. 98mL/kg; p=0.027). The incidence of clinical fluid overload among the study group was markedly lower (11% vs. 44%; p=0.001), with significantly lower CVP at 24h (14.6±3 vs. 16.3±3cmH2O; p=0.02).

Hemodynamic variables.

| Initial | 1h | 6h | 24h | p+ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | |||||

| Control | 82.31±14.03 | 91.04±15.48 | 102.87±16.12 | 107.73±13.67 | 0.001a |

| Study | 85.73±14.22 | 95.64±14.80 | 98.40±16.94 | 105.27±16.32 | 0.001a |

| p | 0.254 | 0.153 | 0.203 | 0.439 | |

| Mean arterial pressure (mmHg) | |||||

| Control | 54.44±14.10 | 54.33±13.52 | 65.51±14.07 | 71.02±11.19 | 0.001a |

| Study | 54.43±8.33 | 64.62±8.82 | 67.29±12.12 | 76.73±10.19 | 0.001a |

| p | 0.994 | <0.001a | 0.522 | 0.013a | |

| Heart rate (beats/min) | |||||

| Control | 169.87±22.42 | 167.78±24.43 | 163.42±23.26 | 155.51±24.04 | 0.01a |

| Study | 184.09±14.95 | 168.0±15.44 | 175.18±15.26 | 158.96±21.77 | 0.001a |

| p | 0.001a | 0.959 | 0.006a | 0.478 | |

| Central oxygen venous saturationb(%) | |||||

| Control | 43.43±18.14 | 53.14±19.35 | 59.13±20.79 | 61.69±15.55 | 0.001a |

| Study | 45.23±13.34 | 56.43±15.03 | 65.42±15.44 | 63.98±10.97 | 0.001a |

| p | 0.601 | 0.371 | 0.107 | 0.422 | |

| Central venous pressureb(cmH2O) | |||||

| Control | 7.09±2.45 | 10.49±3.61 | 13.40±3.04 | 16.33±3.38 | 0.001a |

| Study | 5.25±4.54 | 10.87±2.74 | 13.60±4.72 | 14.67±3.19 | 0.001a |

| p | 0.078 | 0.586 | 0.818 | 0.020a | |

| MAP-CVP (mmHg) | |||||

| Control | 51.78±13.54 | 47.65±13.4 | 56.3±14.5 | 60.50±11.82 | 0.001a |

| Study | 50.99±6.73 | 56.63±8.65 | 57.29±10.8 | 65.95±10.51 | 0.001a |

| p | 0.728 | < 0.001a | 0.718 | 0.023a | |

| Lactate (mmol/L) | |||||

| Control | 4.27±2.88 | 3.0±2.17 | 3.1±3.07 | 2.46±1.87 | 0.001a |

| Study | 3.70±2.06 | 2.89±1.55 | 1.96±0.75 | 1.72±0.8 | 0.001a |

| p | 0.809 | 0.783 | 0.353 | 0.050a | |

| Urine output (mL/kg/h) | |||||

| Control | – | 0.75±0.64 | 1.68±1.12 | 2.4±1.76 | 0.001a |

| Study | – | 0.68±0.54 | 1.82±1.39 | 2.5±1.11 | 0.001a |

| p | – | 0.582 | 0.594 | 0.738 | |

| Cumulative fluid (mL/kg) | |||||

| Control | – | 61.33±10.79 | 75.11±15.47 | 98.2±26.2 | 0.001a |

| Study | – | 70.2±16.0 | 77.2±19.3 | 86.0±24.5 | 0.125 |

| p | – | 0.003a | 0.574 | 0.027a | |

| Features of fluid overloadcn(%) | |||||

| Control | 20(44.4%) | ||||

| Study | 5(11.1%) | ||||

| FEp | 0.001a | ||||

MAP-CVP, perfusion pressure (mean arterial pressure minus central venous pressure) CVP was converted to mmHg; p, p-value of independent samples t-test; p+, p-value or repeated measures ANOVA; FEp, p-value of Fisher's exact probability test.

Data presented by mean±standard deviation.

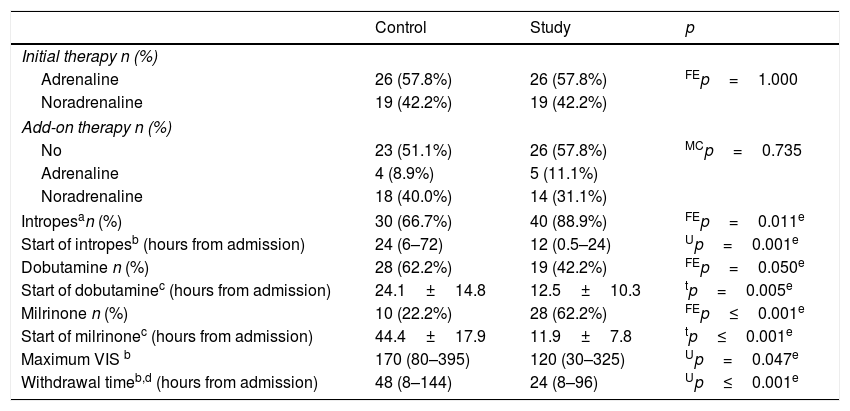

As shown in Table 3, inotropes were more frequently used among the study group (89% vs. 67%; p=0.011). Dobutamine usage predominated among the control group, while milrinone usage predominated among the study group. The mean times for the onset of dobutamine and milrinone use were significantly earlier in the study group (12.5±10.3 vs. 24.1±14.8h; p=0.005 for dobutamine, and 11.9±7.8 vs. 44.4±17.9h; p=0.001 for milrinone). Seven patients in the study group and eight patients in the control group received dobutamine and milrinone simultaneously. In the study group, maximum VIS was significantly lower (120[30–325] vs. 170[80–395]; p=0.047), with markedly earlier withdrawal time (24[8–96] vs. 48[8–144]h; p≤0.001).

Treatment details.

| Control | Study | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial therapy n (%) | |||

| Adrenaline | 26 (57.8%) | 26 (57.8%) | FEp=1.000 |

| Noradrenaline | 19 (42.2%) | 19 (42.2%) | |

| Add-on therapy n (%) | |||

| No | 23 (51.1%) | 26 (57.8%) | MCp=0.735 |

| Adrenaline | 4 (8.9%) | 5 (11.1%) | |

| Noradrenaline | 18 (40.0%) | 14 (31.1%) | |

| Intropesan (%) | 30 (66.7%) | 40 (88.9%) | FEp=0.011e |

| Start of intropesb (hours from admission) | 24 (6–72) | 12 (0.5–24) | Up=0.001e |

| Dobutamine n (%) | 28 (62.2%) | 19 (42.2%) | FEp=0.050e |

| Start of dobutaminec (hours from admission) | 24.1±14.8 | 12.5±10.3 | tp=0.005e |

| Milrinone n (%) | 10 (22.2%) | 28 (62.2%) | FEp≤0.001e |

| Start of milrinonec (hours from admission) | 44.4±17.9 | 11.9±7.8 | tp≤0.001e |

| Maximum VIS b | 170 (80–395) | 120 (30–325) | Up=0.047e |

| Withdrawal timeb,d (hours from admission) | 48 (8–144) | 24 (8–96) | Up≤0.001e |

VIS, Vasopressor Inotropes Score; FEp, p-value of Fisher's exact probability test; MCp, p-value of Mont Carlo's exact probability test; Up, p-value of Mann–Whitney's test; tp, p-value of the independent t-test.

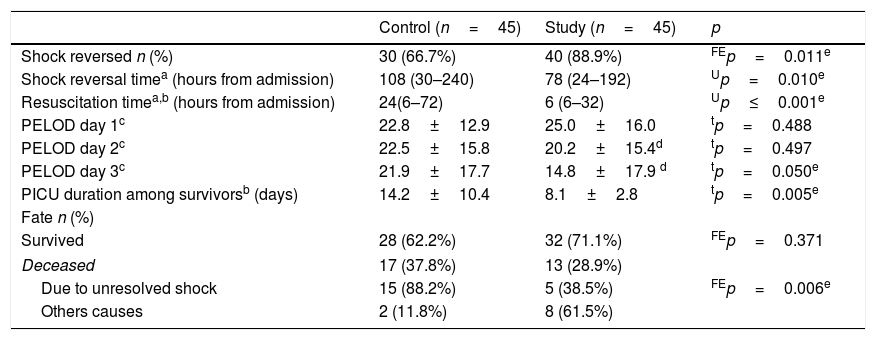

As shown in Table 4, the proportion of children in whom shock reversal was successful was significantly higher (89% vs. 67%; p=0.011), with markedly shorter shock reversal time (3.3[1–8] vs. 4.5[1.3–10] days; p=0.01). Resuscitation time was significantly earlier in the study group (24[6–72] vs. 6[6–32]; p≤0.001).

Primary and secondary outcomes.

| Control (n=45) | Study (n=45) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shock reversed n (%) | 30 (66.7%) | 40 (88.9%) | FEp=0.011e |

| Shock reversal timea (hours from admission) | 108 (30–240) | 78 (24–192) | Up=0.010e |

| Resuscitation timea,b (hours from admission) | 24(6–72) | 6 (6–32) | Up≤0.001e |

| PELOD day 1c | 22.8±12.9 | 25.0±16.0 | tp=0.488 |

| PELOD day 2c | 22.5±15.8 | 20.2±15.4d | tp=0.497 |

| PELOD day 3c | 21.9±17.7 | 14.8±17.9 d | tp=0.050e |

| PICU duration among survivorsb (days) | 14.2±10.4 | 8.1±2.8 | tp=0.005e |

| Fate n (%) | |||

| Survived | 28 (62.2%) | 32 (71.1%) | FEp=0.371 |

| Deceased | 17 (37.8%) | 13 (28.9%) | |

| Due to unresolved shock | 15 (88.2%) | 5 (38.5%) | FEp=0.006e |

| Others causes | 2 (11.8%) | 8 (61.5%) | |

PELOD, Pediatric Logistic Organ Dysfunction; FEp, p-value of Fisher's exact probability test; Up, p-value of Mann–Whitney's test; tp, p-value of the independent samples t-test.

PELOD score improved significantly over time in the study group, being markedly lower on the third day compared with the control group. PICU stay among survivors of the study group was significantly shorter (8±3 vs. 14±10 days; p=0.005).

Although the proportion of deceased children was lower but not statistically significant in the study group (29% [n=13] vs. 38% [n=17]; p=0.371), mortality due to unresolved shock was significantly lower (38% [5/13] vs. 88% [15/17]; p=0.006).

DiscussionShock reversal is the first task that should be fulfilled in pediatric septic shock patients. Han et al. found that each additional hour of persistent shock was associated with>two-folds increased odds of mortality.19 The primary aim of the study was to assess the role of echocardiography in reducing shock reversal time among pediatric septic shock patients. Patients were managed using echocardiography to assess their hemodynamic state and guide changes in therapy, compared with the common assessment on a clinical basis alone. The clinical uses of the echocardiographic findings in children with septic shock and their potential implications for choosing and optimizing vasoactive/inotropic medications have not yet been properly evaluated. Various studies assessed the use of echocardiography in adult ICU patients, yet few addressed the pediatric population.20 Moreover, previous studies of echocardiographic evaluation of SMD provide only a snapshot assessment at the time of the study.7,8 However, the serial echocardiographic monitoring over time performed in the present study overcame this limitation.

The percentage of children in whom shock reversal was successful was significantly higher in the study group (86% [n=40/45] vs. 67% [n=30/45]), with a median of 1.2 days earlier than that in the control group (3.3 vs. 4.5 days). Two studies by Ranjit et al. reported septic shock reversal in 96% (n=46/48) in a prospective study and 77% (n=17/22) in an earlier retrospective study.8,9 Resuscitation time was significantly earlier in the study group (6 vs. 24h) indicating that echocardiography not only led to faster weaning of vasopressor/inotropes, but also to earlier initial hemodynamic stabilization.

Although the proportion of deceased children was lower, but not statistically significant in the study group (29% vs. 38%), the number of deaths due to unresolved shock was significantly lower in the study group, fulfilling the aim of the study. Being a tertiary care hospital's PICU, patients presented late, which was reflected on the high PIM2 score on admission. Ranjit and Kissoon reported a mortality rate of 27%,9 while Raj et al. and Ranjit et al. reported 6.7% and 8%, respectively.7,8 Early shock reversal in the study group was associated with a significant reduction in PICU stay (8±3 vs. 14±10 days). Raj et al. reported a PICU stay of 14±10 days.7

All timely recorded hemodynamic variables significantly improved over time in both groups, due to adherence to current pediatric sepsis guidelines.10 However, the optimization of fluid and vasopressor therapy in the study group, guided by echocardiography, resulted in significant higher MAP and MAP-CVP values at 1 and 24h, due to diastolic pressure improvement. At the end of 24h, CVP was significantly higher in the control group coinciding with the fluid overload clinical features revealed in this group, which were four-fold higher than in the study group (44% vs. 11%). These results can be attributed to the effective role of echocardiography in optimizing fluid therapy. Kelm et al. stated that clinical evidence of fluid overload would commonly reach up to 67% in septic shock patients treated with early directed therapy.21 Recent PICU studies demonstrated the association of poor outcome with fluid overload.22 Although Ranjit et al. used echocardiography within 6h of identification of septic shock to guide therapy, fluid overload was observed in 44% of their patients.8 The great difference between Ranjit's and this study the fact that the present study early and serial echocardiographic monitoring; this allowed a proactive rather than reactive therapeutic intervention. In spite of the significantly higher fluid volume received in the first hour in the study group to treat existing hypovolemia evidenced by echocardiography, the cumulative fluid volume at 24h was significantly lower due to early and successful fluid management that avoided persistent hypovolemia and the need for more fluid.

In the present study, lactate levels markedly improved in the study group to be less than two mmol/L, while they failed to normalize in the control group at 24h. Failure to normalize lactate levels during critical illness has been associated with increased risk of major adverse events.23

Inotropes were used more frequently in the study group (89% vs. 67%) with earlier starting time (12 vs. 24h), as echocardiography allowed early detection of SMD that would not be diagnosed with certainty by clinical examination alone. Beck et al. stated that the marked delay in initiation of vasopressor/inotropic therapy was associated with increased mortality risk in patients with septic shock.24 Dobutamine use predominated in the control group, as it is recommended in the SSC guidelines guided by CVP and Scvo2.10 In turn, milrinone use predominated in the study group. This is due to the fact that, the study group had higher heart rates than the control group, which precluded the use of dobutamine as the first choice, while milrinone, as reported by Tomicic et al., optimizes cardiovascular performance in septic shock without affecting hemodynamic variables.25 Moreover, milrinone accelerates myocardial relaxation,26 thus it was capable of treating diastolic dysfunction uncovered by echocardiography in the present study, in which 70% of SMD patients developed diastolic dysfunction. Yano et al. demonstrated that milrinone is much more efficient at accelerating LV relaxation than dobutamine.27 Sankar et al. reported that increased central venous pressure after initial fluid resuscitation might be an early indicator of diastolic dysfunction, and warrant urgent bedside echocardiography to guide further management.28 Lastly, echocardiography uncovered dobutamine unresponsiveness and failure to improve cardiac output; many patients presented SMD resulting from sepsis-induced desensitization of beta-adrenergic receptors, so milrinone was recommended as it does not act via adrenergic receptors but rather through selective inhibition of phosphodiesterase III, making it immune to the effect of adrenergic receptor desensitization.29,30

Maximum VIS was markedly lower in the study group. Unnecessary doses of vasopressors/inotropes were avoided, because echocardiography allowed tailoring therapy according to the condition of each patient. Gaies et al. concluded that high maximum VIS was strongly associated with a poor outcome when compared with patients with a low maximum VIS.16 The initiation of vasopressors/inotropes withdrawal was significantly earlier in the study group. The key point was the prompt identification of cardiovascular stabilization, through echocardiography, which allowed a smooth withdrawal of the cardiovascular support drugs, thus allowing early shock reversal. No previous published studies reported the initial time of vasopressors/inotropes withdrawal and its impact on the patients’ outcome.

The main strength of the current study was the fact that echocardiography was performed serially, rather than once after admission. This was a randomized prospective study with sufficient sample size. The main limitations of the study are the fact that it was a single-center study and that over 50% of patients included were infants.

Echocardiography provides essential data that cannot be obtained by clinical examination alone. Serial echocardiography allowed optimal adjustment of therapy, significantly improved all hemodynamic parameters, and reduced shock reversal time. The authors recommend that PICU resident curricula should include echocardiogram education focused on hands-on training to allow the incorporation of echocardiography into septic shock management.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: EL-Nawawy AA, Abdelmohsen AM, Hassouna HM. Role of echocardiography in reducing shock reversal time in pediatric septic shock: a randomized controlled trial. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2018;94:31–9.