To investigate the association between the perception of body weight (as above or below the desired) and behaviors for body weight control in adolescents.

MethodsThis was a cross-sectional study that included 1051 adolescents (aged 15–19 years) who were high school students attending public schools. The authors collected information on the perception of body weight (dependent variable), weight control behaviors (initiative to change the weight, physical exercise, eating less or cutting calories, fasting for 24h, taking medications, vomiting, or taking laxatives), and measured body weight and height to calculate the body mass index and then classify the weight status. Associations were tested by multinomial logistic regression analysis.

ResultsAdolescents of both sexes who perceived their body weight as below the expected weight took more initiatives to gain weight, and those who perceived themselves as overweight made more efforts to lose weight. In adolescents who perceived themselves as overweight, the behavior of not taking medication was associated with the outcome only in boys (Odds Ratio=8.12), whereas in girls, an association was observed with the variables eating less, cutting calories, or avoiding fatty foods aiming to lose or avoid increasing body weight (Odds Ratio=3.39). Adolescents of both sexes who practiced exercises were more likely to perceive themselves as overweight (male Odds Ratio=2.00; Odds Ratio=1.93 female).

ConclusionThe perception of the body weight as above and below one's expected weight was associated with weight control behaviors, which were more likely to result in initiatives to lose and gain weight, respectively.

Verificar a associação da percepção (acima ou abaixo) do peso corporal esperado com os comportamentos para controle de peso em adolescentes.

MétodosEstudo transversal, realizado com 1051 adolescentes (15 a 19 anos), do ensino médio de escolas públicas estaduais. Foram coletadas informações sobre a percepção do peso corporal (variável dependente), comportamentos de controle de peso (iniciativa para mudar o peso, prática de exercícios físicos, comer menos ou cortar calorias, ficar 24h sem comer, tomar medicamentos, vomitar ou tomar laxantes) e aferidas as medidas de massa corporal e estatura para cálculo do índice de massa corporal e classificação do status do peso. As associações foram testadas por meio da regressão logística multinomial.

ResultadosAdolescentes de ambos os sexos com percepção do peso corporal abaixo do peso esperado apresentaram mais iniciativas para ganhar peso e aqueles que se percebiam acima do peso tiveram mais iniciativas para perder peso. Nos adolescentes que se percebiam acima do peso, o comportamento de não tomar medicamento esteve associado ao desfecho apenas nos rapazes (OR=8,12), enquanto nas moças observou-se associação com comer menos, cortar calorias ou evitar alimentos gordurosos para perder ou para não aumentar o peso corporal (OR=3,39). Adolescentes de ambos os sexos que realizavam exercício físico tiveram maior chance de se perceber acima do peso (masculino OR=2,00; feminino OR=1,93).

ConclusãoA percepção do peso acima e abaixo do peso esperado esteve associada aos comportamentos de controle de peso, onde respectivamente, tinham mais chances em realizar iniciativas para perder e para ganhar peso.

The concern in attaining a body shape that is closer to the standards established by society is frequent among adolescents, who long for an appearance that they consider to be adequate, with specific characteristics for each gender.1 In seeking the desired body weight, it is common for individuals of this age group to adopt behaviors for weight control, which are most often inadequate and can cause health damages.2 Studies have identified that weight control behaviors are associated with body weight perception.2–4 This body weight perception has been defined as the way an individual perceives his/her own body in relation to the weight status or condition, which can be perceived as above, below, or at the expected weight.4–6

In this sense, research has indicated that the main weight-control behaviors related to body weight perception in adolescents include fasting, dieting, laxative use, physical exercise, and self-medication with diet pills.2,7 Additionally, the association of some behaviors such as skipping meals, replacing foods, vomiting, smoking more cigarettes, and going on extreme diets can be observed, specifically in cases where the individual perceives his/her weight as above the expected or overweight.3,8 Moreover, there is evidence suggesting that overweight perception is associated with diets for weight control, regardless of the actual weight status.9

It is noteworthy that the information about the association between body weight perception and weight control behaviors in adolescents are mainly obtained from studies carried out in Asian4,6,8,10,11 and European countries,2,3,7 as well as in the United States.8,12 In turn, studies that investigated the association between body weight perception and behaviors related to weight control in Brazil are still scarce. At the national level, there are studies on body weight perception13,14 and body weight control habits,15,16 analyzed alone. Additionally, in the researched literature, both national and international, no associations were specifically found for body weight perception below the expected and weight control behaviors.

Considering the health risks associated with the way individuals perceive their body weight, especially in relation to the adoption weight control behaviors, it is necessary to identify and monitor the conducts so that there is no damage to the adolescents’ health and there is higher awareness by healthcare professionals regarding this age group. Consistent with this need, the aim of this study was to verify the association between body weight perception (above or below the expected) and body weight control behaviors in adolescents.

Materials and methodsThis cross-sectional study is part of the macroproject “Brazilian Guide for the Evaluation of Physical Fitness Related to Health and Life Habits - Stage I”, approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina (protocol No. 746.536/2014), carried out in 2014.

The study population consisted of adolescents attending high school, regularly enrolled in state public schools in the municipality of São José, state of Santa Catarina, Brazil. During the study period, 5182 students were enrolled in the public high school network of this municipality.17

In order to calculate the sample size, the equation proposed by Luiz and Magnanini18 was used, adopting a confidence level of 1.96 (95% confidence interval), a tolerable error of five percentage points, a prevalence of 50% (unknown outcome), and design effect of 1.5. To minimize possible losses related to possible refusals to participate in the study, 20% were added, plus an extra 20% for the control of confounding variables. Thus, the minimum sample size would comprise 751 students.

The sample selection process was determined in two stages: stratified by state public high schools and by cluster of classrooms (considering the school shift and the school year), in which all those present in the classroom on the day of the data collection were invited to participate. Except for state schools with Youth and Adult Education and those with programs that included students with some type of intellectual disability, the others were considered eligible for study participation. In the first stage, the school density (size: small, with less than 200 students; medium-sized, with 200 up to 499 students; and large, with 500 students or more) was used as a stratification criterion. In the second stage, the study shift (morning, afternoon, evening, and full-time) and the school year (first, second, and third years of high school) were considered.

Data collection was carried out in the second half of 2014, at the premises of the schools chosen by drawing lots that agreed to participate in the study, on days and times scheduled with the school staff. Initially, the researchers contacted the students from the drawn groups to explain the objectives and importance of the study and to invite them to participate in it. At that moment, the students received the informed consent form, which was to be taken home and to be shown to their parents and signed by them (for students under the age of 18). Those who were 18 years of age or older could sign their own informed consent. Moreover, all students (regardless of age) received a term of assent to be signed by themselves.

At a second moment, the researchers returned to the schools to apply the questionnaires and measure body mass and height. This stage was carried out with the students who voluntarily wished to participate and had handed in all the duly signed necessary documents. Pregnant women and individuals with any physical disability were not included and received clarification on the reason for such decision. The questionnaires were self-answered by the participants, in the presence of the researchers, who were available to answer any questions.

The dependent variable of this study was body weight perception, investigated based on the question: “How do you describe your body weight?” The five response options were grouped into three categories: below the expected weight (much lower than what I expect+a little lower than what I expect); at the expected weight; above the expected weight (somewhat higher than what I expect+much higher than what I expect), as employed by other studies that investigated this topic.4,7,10 This question was taken from the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) Questionnaire, translated and adapted by Lopes.19

As independent variables, the weight control behaviors adopted by the adolescents were investigated through the questions of the YRBS questionnaire19:

- a)

“Have you taken any initiative to change your weight?” (options: lose body weight, gain body weight, maintain body weight, I did not take any initiative);

- b)

“During the last 30 days, did you do any type of exercise to lose or avoid increasing your body weight?” (options: yes; no);

- c)

“During the last 30 days, did you eat less, cut calories, or avoided fatty foods to lose or avoid increasing your body weight?” (options: yes; no);

- d)

“During the last 30 days, did you refrained from eating for 24h or more to lose or avoid increasing your body weight?” (options: yes; no);

- e)

“During the last 30 days, did you take any medication, powder, or liquid without medical advice to lose or avoid increasing your body weight?” (options: yes; no);

- f)

“During the last 30 days, did you vomit or take laxatives to lose or avoid increasing your body weight?” (options: yes, no).

The weight status obtained through the body mass index (BMI) calculation (body mass/height2) was used to adjust the variables in the multinomial logistic regression analysis. Body mass was measured using a digital scale (G Tech Pro®, Pacific Palisades, CA, USA), with a capacity of up to 150kg and a resolution of 100g. Height was measured in a stadiometer (Sanny®, São Paulo, Brazil) with a resolution of 0.1cm. To perform both measures, the procedures of the International Standards for Anthropometry Assessment (ISAK)20 were followed. The weight status, according to BMI, was classified according to the cutoff points for adolescents, stratified by gender and age.21,22 Due to the small number of underweight (n=73) and obese (n=61) participants, they were grouped with those of normal weight and excess weight, respectively, forming the categories “normal weight” and “excess weight”.

In the present study, only adolescents aged 15–19 years were included. Descriptive (mean, standard deviations, and frequency distribution) and inferential statistics (t-test for independent samples, chi-squared, and multinomial logistic regression) were used. The normality of data was verified using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The multinominal regression was used in the association tests between body weight perception and the other independent weight control variables, as the dependent variable had three categories.

The expected weight category was used as a reference for body weight perception. The independent variables with p<0.20 in the crude analyses were added together with the weight status in the adjusted model.23 The variable initiative for weight change was not added to the adjusted analyses due to its collinearity with the other variables. The significance level was set at 5%. All analyses were performed using SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0. NY, USA).

ResultsA total of 1148 students participated in the macroproject, of whom 97 were excluded from the analyses of this study (15 because they did not respond to the dependent variable and 82 because they were younger than 15 years or older than 19 years). Therefore, the final sample consisted of 1051 adolescents (girls=53.9%), with a mean age of 16.29 years (sd=1.04).

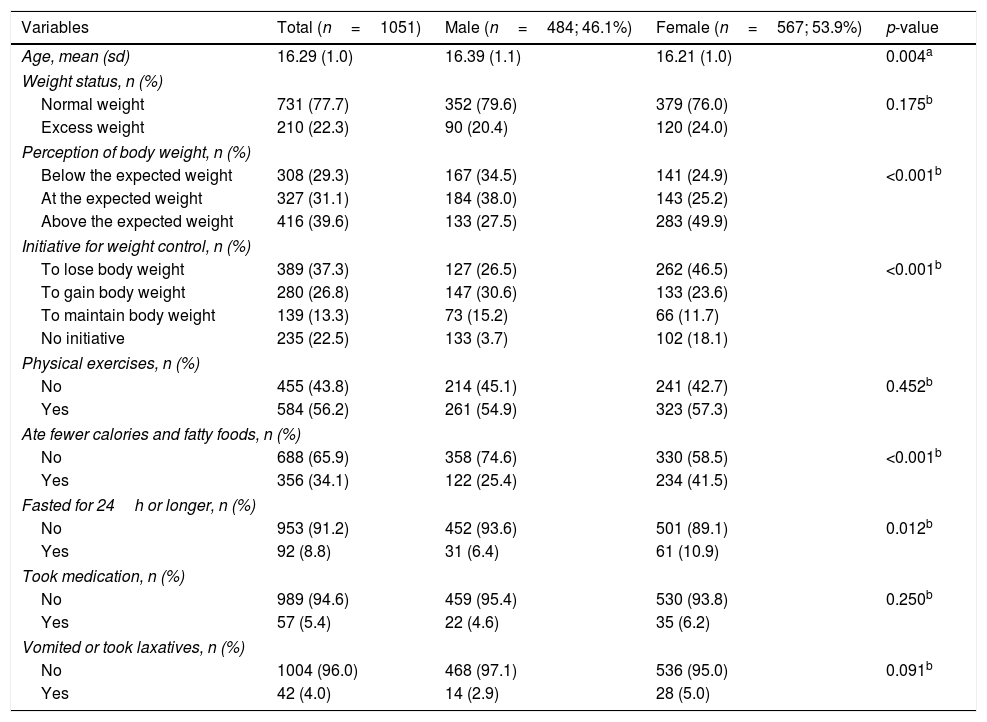

Regarding the sample's characteristics, it was observed that, when compared with boys, girls more frequently perceived themselves as above the expected body weight (49.9%), had taken more initiatives to lose weight (46.5%), avoided eating calories and fatty foods (41.5%), and refrained from eating for 24h or more (10.9%). No difference was observed between the genders regarding the performance of physical exercises to lose weight or avoid increasing weight, use of medications (powder or liquid), and vomiting or use of laxatives (Table 1).

Overall characteristics of adolescents in the total sample and stratified by gender. São José, SC, Brazil. 2014.

| Variables | Total (n=1051) | Male (n=484; 46.1%) | Female (n=567; 53.9%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (sd) | 16.29 (1.0) | 16.39 (1.1) | 16.21 (1.0) | 0.004a |

| Weight status, n (%) | ||||

| Normal weight | 731 (77.7) | 352 (79.6) | 379 (76.0) | 0.175b |

| Excess weight | 210 (22.3) | 90 (20.4) | 120 (24.0) | |

| Perception of body weight, n (%) | ||||

| Below the expected weight | 308 (29.3) | 167 (34.5) | 141 (24.9) | <0.001b |

| At the expected weight | 327 (31.1) | 184 (38.0) | 143 (25.2) | |

| Above the expected weight | 416 (39.6) | 133 (27.5) | 283 (49.9) | |

| Initiative for weight control, n (%) | ||||

| To lose body weight | 389 (37.3) | 127 (26.5) | 262 (46.5) | <0.001b |

| To gain body weight | 280 (26.8) | 147 (30.6) | 133 (23.6) | |

| To maintain body weight | 139 (13.3) | 73 (15.2) | 66 (11.7) | |

| No initiative | 235 (22.5) | 133 (3.7) | 102 (18.1) | |

| Physical exercises, n (%) | ||||

| No | 455 (43.8) | 214 (45.1) | 241 (42.7) | 0.452b |

| Yes | 584 (56.2) | 261 (54.9) | 323 (57.3) | |

| Ate fewer calories and fatty foods, n (%) | ||||

| No | 688 (65.9) | 358 (74.6) | 330 (58.5) | <0.001b |

| Yes | 356 (34.1) | 122 (25.4) | 234 (41.5) | |

| Fasted for 24h or longer, n (%) | ||||

| No | 953 (91.2) | 452 (93.6) | 501 (89.1) | 0.012b |

| Yes | 92 (8.8) | 31 (6.4) | 61 (10.9) | |

| Took medication, n (%) | ||||

| No | 989 (94.6) | 459 (95.4) | 530 (93.8) | 0.250b |

| Yes | 57 (5.4) | 22 (4.6) | 35 (6.2) | |

| Vomited or took laxatives, n (%) | ||||

| No | 1004 (96.0) | 468 (97.1) | 536 (95.0) | 0.091b |

| Yes | 42 (4.0) | 14 (2.9) | 28 (5.0) | |

n, absolute frequency; %, relative frequency; sd, standard deviation.

The boys who perceived themselves below the expected body weight had a 4.23-fold (95% CI: 2.48–7.21) higher chance of having taken initiatives to increase body weight, while those who perceived themselves as above the expected weight had a 12.19-fold (95% CI: 6.31–23.57) higher chance of having taken initiatives to lose weight. Similarly, girls who perceived themselves as underweight had a 5.85-fold (95% CI: 3.08–11.12) higher chance of having taken initiatives to increase body weight and those with an excess weight perception had a 12.38-fold (95% CI: 6.70–22.88) higher chance of having taken initiatives to lose weight (data not shown in the tables).

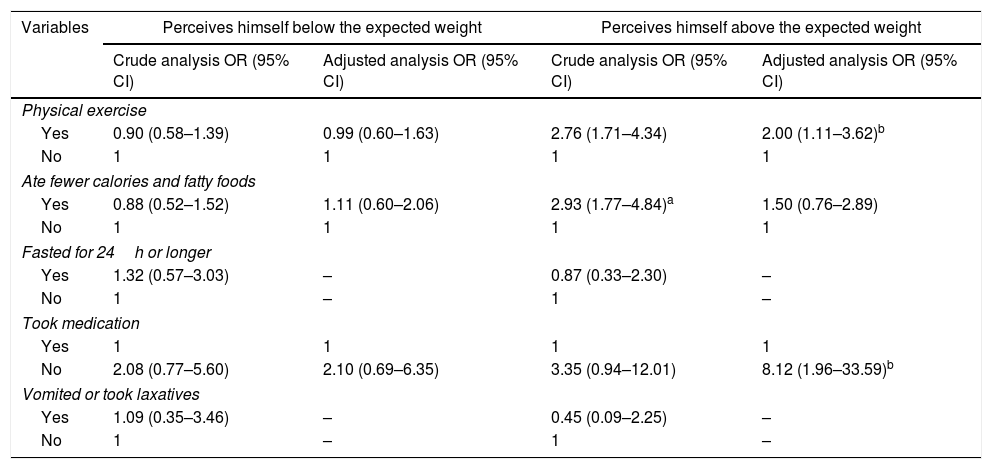

Tables 2 and 3 present the associations between body weight perception and the variables of weight control behaviors for male and female adolescents, respectively. Boys who did not take medications (OR=8.12, 95% CI: 1.96–33.59) and who exercised had a greater chance (OR=2.00, 95% CI: 1.11–3.62) of perceiving themselves as above the expected weight (Table 2).

Association between body weight perception and weight control behaviors in male adolescents. São José, SC, Brazil. 2014.

| Variables | Perceives himself below the expected weight | Perceives himself above the expected weight | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude analysis OR (95% CI) | Adjusted analysis OR (95% CI) | Crude analysis OR (95% CI) | Adjusted analysis OR (95% CI) | |

| Physical exercise | ||||

| Yes | 0.90 (0.58–1.39) | 0.99 (0.60–1.63) | 2.76 (1.71–4.34) | 2.00 (1.11–3.62)b |

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Ate fewer calories and fatty foods | ||||

| Yes | 0.88 (0.52–1.52) | 1.11 (0.60–2.06) | 2.93 (1.77–4.84)a | 1.50 (0.76–2.89) |

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Fasted for 24h or longer | ||||

| Yes | 1.32 (0.57–3.03) | – | 0.87 (0.33–2.30) | – |

| No | 1 | – | 1 | – |

| Took medication | ||||

| Yes | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| No | 2.08 (0.77–5.60) | 2.10 (0.69–6.35) | 3.35 (0.94–12.01) | 8.12 (1.96–33.59)b |

| Vomited or took laxatives | ||||

| Yes | 1.09 (0.35–3.46) | – | 0.45 (0.09–2.25) | – |

| No | 1 | – | 1 | – |

OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Adjusted for all variables that showed p<0.20 in the crude analysis and by weight status.

The reference category for weight perception was: at the expected weight.

Association between body weight perception and weight control behaviors in female adolescents. São José, SC, Brazil. 2014.

| Variables | Perceives herself below the expected weight | Perceives herself above the expected weight | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude analysis OR (95% CI) | Adjusted analysis OR (95% CI) | Crude analysis OR (95% CI) | Adjusted analysis OR (95% CI) | |

| Physical exercise | ||||

| Yes | 1.04 (0.61–1.77) | 1.01 (0.55–1.87) | 4.30 (2.75–6.72)a | 1.93 (1.09–3.40)b |

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Ate fewer calories and fatty foods | ||||

| Yes | 0.57 (0.32–1.01) | 0.60 (0.32–1.14) | 4.28 (2.75–6.66)a | 3.39 (1.95–5.88)a |

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Fasted for 24h or longer | ||||

| Yes | 0.57 (0.16–2.00) | 0.53 (0.12–2.31) | 4.17 (1.84–9.47)b | 2.49 (0.88–7.09) |

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Took medication | ||||

| Yes | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| No | 1.39 (0.43–4.49) | 0.86 (0.18–4.20) | 0.58 (0.24–1.39) | 0.73 (0.19–2.93) |

| Vomited or took laxatives | ||||

| Yes | 0.60 (0.14–2.58) | 0.86 (0.18–4.20) | 2.12 (0.78–5.76) | 0.74 (0.19–2.93) |

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

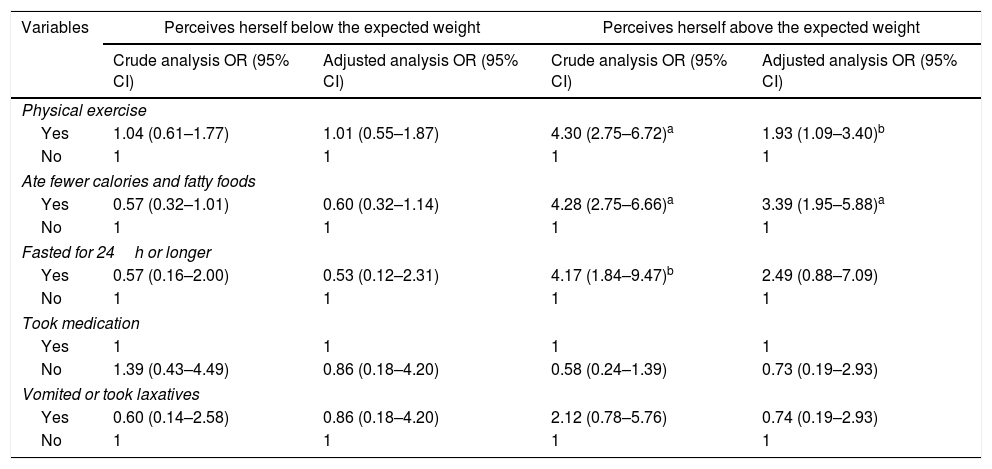

OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Adjusted for all variables that showed p<0.20 in the crude analysis and by weight status.

The reference category for weight perception was: at the expected weight.

Girls who perceived themselves as above the expected body weight were more likely to eat less or avoid eating fatty foods (OR=3.39; 95% CI, 1.95–5.88). Those who performed physical exercises to lose weight had a greater chance (OR=1.93, 95% CI: 1.09–3.40) of perceiving themselves as above the expected weight (Table 3).

DiscussionThe results of the present study demonstrated that, among the specific behaviors for weight control, not taking medication (powder or liquid) was associated with weight perception as above the expected in boys, while eating less, cutting calories, or avoiding fatty foods to lose or avoid increasing body weight were associated with this outcome in girls. Adolescents of both genders who exercised to lose or avoid gaining weight had a greater chance of perceiving themselves as above the expected body weight. No associations were observed between weight control behaviors and body weight perception below the expected in neither gender. Nevertheless, having taken some initiative for weight control (losing, gaining, or maintaining body weight) was associated with the perception of body weight below or above the expected in both genders.

Regarding such weight-change initiatives, it is understood that adolescents who perceived themselves as above or below their expected body weight did not wish to remain in their current weight, showing an interest in losing or gaining weight, respectively, in order to achieve what they believed to be the adequate weight. Similar results regarding weight perception above the expected, were observed by Yost et al.5 in female adolescents and by Oellingrath et al.7 in adolescents of both genders. Moreover, in the study by Lee et al.,11 adolescents who perceived themselves as overweight were those most interested in participating in a school weight management program, when compared with those who perceived themselves as having normal or underweight. Thus, it appears that body weight perception influences the behaviors adopted by adolescents; those who perceive themselves as above the expected weight are particularly more concerned with getting involved in strategies for weight control.

Regarding the associations between body weight perception and specific weight control behaviors, it was observed that boys who perceived themselves as above the expected weight had a greater chance of not using medications to lose or avoid increasing weight, when compared with those who perceived themselves as having the expected weight. Divergent findings were found in the study by Ursoniu et al.,2 in which Romanian adolescents who perceived themselves as overweight were more likely to consume diet pills, powders, or tea to lose or maintain weight. It is believed that the results of the Ursoniu et al.2 study are more common than expected in researches on the subject; however, it is suggested that, in the present study, adolescents who perceived themselves at the expected weight were those with the highest rates of medication use for weight control, possibly aiming at maintaining the current weight.

In the female gender, eating less, cutting calories, or avoiding fatty foods were weight control behaviors associated with perceived weight above the expected. In adolescents, studies have identified that individuals who perceived themselves as overweight were more likely to adopt calorie restriction behaviors.2,8 Moreover, evidence has indicated that adopting restrictive eating behaviors to achieve the ideal body is a more common habit in the female gender, since the lower intake of calories from food can prevent the increase in body weight.8,11,24–26

Moreover, evidence in the literature has also shown an association between physical exercise and body weight perception.2,8 In the present study, adolescents of both genders who exercised were more likely to perceive themselves as being overweight. This result can be explained, for instance, by the findings of Guedes et al.,27 in which overweight and obese adolescents and young individuals reported the possibility of weight control and physical appearance improvement as the main reasons for exercising.

Therefore, it can be assumed that the adolescents of the present study acknowledge the benefits of physical exercise for weight control and engage in such practices to achieve the expected body weight. It should be emphasized that among the behaviors for weight control assessed in this study, physical exercise is a healthy behavior that should be encouraged (at adequate frequency and intensity) in the young population, together with a balanced diet.

The results of the present study should be interpreted considering the following limitations: the questions regarding specific weight-control behaviors were related to the intention to reduce body weight, or avoid increasing it, and questions related with intentional weight gain behaviors were not asked. Additionally, a memory bias may have influenced the findings, as adolescents might have had difficulty remembering whether they adopted some type of weight-control behavior, since they had to remember facts that occurred during a considerable period of time (last 30 days). However, the present study reinforces the need to understand how adolescents adopt weight control behaviors through a probabilistic sampling, and highlights the lack of information about the national adolescent's population. It may also provide insight into the influence of body weight perception and body image on weight control behaviors and, consequently, greater care related to the adolescents’ health.

As conclusions, it was observed that body weight perception was associated with weight control behaviors. Initiatives to change or maintain weight were associated, in both genders, with the perception of weight as being below or above the expected. The use of medication (powder or liquid) was negatively associated with boys who perceived themselves as above the expected weight; and eating less, cutting calories, or avoiding fatty foods to lose or avoid increasing body weight was positively associated with girls who perceived themselves as being above the expected weight. Adolescents of both genders who exercised were more likely to perceive themselves as above the expected weight.

Considering the difficulty adolescents have in changing behaviors, it is necessary to promote discussions at school regarding less aggressive forms for the adolescents to achieve the body shape they expect, such as through planned physical and nutritional practices supervised by a qualified professional. Programs aimed at adolescent health should also be more widely available, contributing to a reduction in inadequate behaviors related to weight control and other risk behaviors.

It is also suggested that further studies on the subject investigate whether the perception of body weight by adolescents is related to esthetic or health factors, since different motivations for the way individuals perceive themselves have distinct implications on their physical and mental health.

FundingConselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico – CNPq, Universal edict (n. 472763/2013-0).

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

To the Regional Education Management (GERED) of the 18th region of the municipality of São José-SC, for their cooperation and authorization of this study, as well as to the schools and students that agreed to participate in the macroproject. To Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) for the funding.

Please cite this article as: Frank R, Claumann GS, Felden ÉP, Silva DA, Pelegrini A. Body weight perception and body weight control behaviors in adolescents. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2018;94:40–7.