To identify the prevalence and associated factors with the performance of the Guthrie test, hearing, and red reflex screening tests in Brazil.

MethodsThis was a population-based, cross-sectional study that analyzed data on 5,231 children under 2 years of age participating in the National Health Survey of 2013. The study described the prevalence and Confidence Intervals (95% CI) of the three neonatal screening tests performed, in any period, and their association with the country's regions, skin color/ethnicity, private health insurance, and per capita household income. Logistic regression models were used, and odds ratios were calculated by incorporating sample weights.

ResultsThe prevalence of Guthrie test screening in Brazil at any time of life was 96.5%, that of the newborn hearing screening was 65.8% and that of the red reflex screening test was 60.4%. The performance of the three screening tests was significantly higher among children whose mothers/guardians reported higher per capita household income, who lived in the South and Southeast regions, and who had private health insurance (p<0.001). There was no statistically significant difference regarding the performance of the tests according to skin color/ethnicity (p>0.05). The same inequalities were verified when the tests were performed during the recommended periods, with a strong socioeconomic gradient.

ConclusionsThere are inequalities in the performance of neonatal screening tests in the country, and also in the performance of these tests during the periods established in the governmental guidelines. The guarantee of the performance of these tests in a universal and public health system, as in Brazil, should promote equity and access to the entire population.

Identificar prevalência e fatores associados à realização dos testes do pezinho, da orelhinha e do olhinho no Brasil.

MétodoEstudo transversal analítico de base populacional que analisou os dados de 5.231 crianças menores de dois anos participantes da Pesquisa Nacional de Saúde (2013). Foram descritas prevalências e intervalos de confiança (95% IC) da realização dos três testes de triagem neonatal, em qualquer período, e sua associação com as regiões do país, cor/etnia, posse de plano de saúde e renda domiciliar per capita. Empregaram-se modelos de regressão logística e calcularam-se as odds ratio e incorporaram-se os pesos amostrais.

ResultadosA prevalência de realização do teste do pezinho no Brasil em qualquer momento de vida foi de 96,5%; do teste da orelhinha de 65,8% e do teste do olhinho de 60,4%. A realização dos três testes de triagem foi significativamente maior entre as crianças cujas mães/responsáveis reportaram maior renda domiciliar per capita, residiam nas regiões Sul e Sudeste e tinham plano de saúde (p<0,001). Não houve diferença estatisticamente significativa na realização dos testes segundo cor/etnia (p>0,05). As mesmas desigualdades foram verificadas para a realização dos testes no período preconizado, com forte gradiente socioeconômica.

ConclusõesExistem desigualdades na realização dos testes de triagem neonatal no país e, também, na realização desses dentro dos prazos previstos nas diretrizes governamentais. A garantia destes testes em um sistema universal e público como no Brasil deveria promover a equidade e o acesso a toda a população.

Neonatal screening is a component of public policies in several countries and refers to the identification of diseases or disorders from birth until the 28th day of life, allowing their early treatment or management.1 Screening is expected to provide a better prognosis for newborns diagnosed with a health problem, preventing or mitigating future disorders and reducing the burden of morbidity and mortality.1–3

In Brazil, the National Neonatal Screening Program recommends that the newborn be discharged from the hospital after undergoing the Red Reflex Test (Teste do Olhinho) and the Pulse Oximetry Test (Teste do Coraçãozinho), in addition to the Guthrie Test (Teste do Pezinho), between the 3rd and 5th days of life, and the newborn Hearing Test (Teste da Orelhinha) in the first month of life.4 Although the universalization of these tests is the aim of the program, there are demographic differences regarding their access.5 Only about one-third of the newborns in the world are submitted to neonatal screening, since several countries do not have yet national neonatal screening programs.6 Some Latin American countries, such as Cuba, Chile, and Uruguay, covered more than 99% of their newborns with the neonatal screening policies in the year 2015, while Brazil in 2013 had a national coverage of 83%.7 Furthermore, despite the recommendation to perform the Guthrie test up to the 5th day of life, a significant proportion is performed only after 8 days of life.8

The national reality still shows significant regional discrepancies in the performance of screening tests.5 Moreover, in 2016, Pinheiro et al.9 reported a higher prevalence of Guthrie test in births performed in the private healthcare network (99.4% vs. 89.6%). Such inequalities persist even at a time when neonatal screening tests are being expanded, a fact that has been observed since the beginning of the 2000s in Brazil.5,10–12 Despite their relevance, surveillance analyses of these inequalities have been directed to the regional differences, and there are no studies at the national level on the inequalities related to neonatal screening access according to individual characteristics, thus justifying the importance of the present study. This study aims to analyze the differences in the performance of biological, hearing and red reflex screening tests in Brazil, according to demographic and socioeconomic characteristics.

MethodsThis is an analytical cross-sectional study that used data from the National Health Survey (Pesquisa Nacional de Saúde – PNS) of 2013. The PNS is a home-based national survey developed in a partnership between the Ministry of Health and the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística – IBGE). Its microdata are of public domain, available on the IBGE13 website. For this study, the data were obtained in March 2018.

The PNS aims to analyze the health status and the use of health services by the population. The study was carried out using the cluster sampling technique and was separated into three stages. In the first stage, the set of census sectors, based on the 2010 Demographic Census, comprised the Primary Sampling Units (PSUs). The second stage consisted of the households; the third stage, of the residents aged 18 or older in each household. Based on the selected PSUs, a fixed number of private households were chosen by simple random sampling. Finally, in each of the selected households, an adult was chosen by drawing lots to answer the detailed PNS questionnaire.14

Data collection took place between 2013 and 2014. A total of 81,254 households were selected and 64,348 individual interviews were carried out with the selected adult residents. Based on the PNS sample, it is possible to estimate indicators for the Brazilian federative units, capital cities, and metropolitan regions. More methodological details of the PNS are described in a previous publication.14 Among the subjects investigated in the PNS is the health of children under 2 years of age. Information regarding this group was obtained from the children's mothers or guardians and was related with the use of health care services, feeding, vaccination, and neonatal screening tests. For the present study, the outcomes were calculated using the information provided in Module L and refer to children under 2 years of age residing in the selected households. In total, data were collected on 5231 children.

The studied outcomes in the present study were the performance of the Guthrie test and the hearing and red reflex screening tests, in any period, categorized as ‘yes’ and ‘no’. They were analyzed according to the regions of residence (North, Northeast, South, Southeast, Midwest), self-reported skin color/ethnicity of the respondent (White, Black, Mixed-race; due to the a small number of people that self-reported as Asian and Native Brazilian, these groups were excluded from the analysis), having private health insurance at the time of the interview (yes/no), and per capita household income (the total amount in Brazilian reals received by the household in the previous month, divided by the number of people living in that household. The final value was categorized in quintiles). Subsequently, the prevalence was also estimated according to the exploratory variables of the performance of the red reflex test and Guthrie test in the first week of life, and of the newborn hearing test in the first month, as recommended by the Ministry of Health.1

The data were analyzed using the Stata 14 statistical package (StataCorp LP – College Station, Texas, United States), considering the design effect and the sample weights. For the analyses, the prevalence of the three tests according to the sociodemographic characteristics, with their respective 95% confidence intervals (95% CI), was calculated, and the chi-squared test was used to identify the distribution differences. Subsequently, the univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed, calculating the odds ratio and its 95% CI as a measure of association. The stepwise-forward procedure was used.15 The level of significance was set at p<0.05 in all analyses.

The PNS was approved by the National Commission for Ethics in Research (Comissão Nacional de Ética em Pesquisa – CONEP) of the National Health Council (Conselho Nacional de Saúde – CNS) in June 2013, under Certificate of Presentation for Ethical Assessment (CAAE) n° 10853812.7.0000.0008. Therefore, this study follows the ethical precepts contained in Resolution n° 466 of the National Health Council (2012) in full.

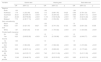

ResultsA total of 5231 children under the age of two were included in this study. Regarding the tests performed in any period, 96.5% answered that the newborn was submitted to the Guthrie test. However, only 65.8% of the respondents confirmed that the newborn was submitted to the hearing screening test and 60.4%, to the red reflex test (Table 1). Two-thirds of the adult respondents lived in the South or Southeast regions, approximately half were white, and 29.5% had private health insurance.

Distribution of the sample and prevalence (95% CI) of the Guthrie, hearing, and red reflex tests. National Health Survey, Brazil, 2013.

| Variable | n (%) | Guthrie test (%) (95% CI) | Hearing test (%) (95% CI) | Red reflex test (%) (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regions | ||||

| North | 1569 (30.0) | 89.0 (86.1/91.4) | 41.7 (37.3/46.3) | 36.1 (32.1/40.2) |

| Northeast | 1569 (30.0) | 93.6 (91.9/94.9) | 44.1 (40.4/47.8) | 35.7 (32.3/39.3) |

| Midwest | 644 (12.3) | 98.4 (96.7/99.2) | 59.2 (54.4/63.8) | 50.0 (44.9/55.1) |

| Southeast | 920 (17.6) | 99.5 (98.5/99.8) | 83.5 (80.2/86.3) | 83.0 (79.7/85.9) |

| South | 529 (10.1) | 99.4 (98.3/99.7) | 89.4 (85.0/92.6) | 81.1 (76.6/84.8) |

| Skin color/ethnicity | ||||

| White | 2224 (42.8) | 97.6 (96.9/98.2) | 75.6 (73.5/77.6) | 70.8 (68.7/72.9) |

| Black | 278 (5.4) | 95.7 (94.5/96.7) | 55.5 (51.6/59.2) | 53.6 (50.2/56.9) |

| Mixed-race | 2690 (51.8) | 95.4 (94.5/96.1) | 57.1 (54.3/59.7) | 50.6 (48.1/53.1) |

| Private health insurance | ||||

| Yes | 1264 (29.5) | 99.4 (99.0/99.4) | 89.5 (87.1/91.4) | 84.1 (81.8/86.1) |

| No | 3967 (70.5) | 95.2 (94.3/95.9) | 55.6 (53.3/57.8) | 50.2 (47.9/52.5) |

| Income | ||||

| 1st quintile | 1824 (30.2) | 91.9 (90.1/93.4) | 43.4 (40.6/46.2) | 38.3 (35.6/41.1) |

| 2nd quintile | 1312 (25.0) | 97.2 (96.1/97.9) | 60.2 (57.4/62.9) | 53.2 (50.6/55.7) |

| 3rd quintile | 858 (18.3) | 99.0 (98.6/99.2) | 78.5 (75.6/87.2) | 72.1 (67.9/75.9) |

| 4th quintile | 651 (14.5) | 99.1 (98.6/99.4) | 85.1 (80.3/88.9) | 82.7 (78.6/86.2) |

| 5th quintile | 586 (12.0) | 99.3 (99.1/99.4) | 90.4 (88.8/91.8) | 85.7 (83.2/88.0) |

| Total | 5231 (100) | 96.5 (95.8/97.0) | 65.8 (63.9/67.7) | 60.4 (58.5/62.3) |

n, total number; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

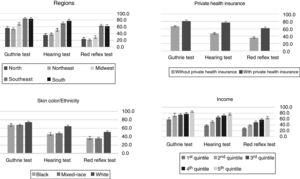

Regarding the performance of these tests, a higher proportion of adequacy was observed in the South and Southeast regions for all tests, whereas a lower proportion was observed in the North and Northeast regions (Fig. 1). It was also identified that the adequacy was higher in children whose mothers or guardians were white, had private health insurance, and was from the wealthiest strata of the sample, with a clear dose-response effect in the latter case. In all the analyses, the differences between the categories were higher in the red reflex and newborn hearing screening tests.

The univariate analysis (Table 2) showed a positive association between the performance of the Guthrie test with the per capita household income, the region of residence, and having private health insurance. For the newborn hearing screening and red reflex tests, in addition to those variables, the outcomes were associated with skin color/ethnicity, with a higher chance of the tests being performed in whites.

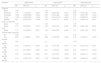

Univariate logistic regression analysis for the performance, at any period, of the Guthrie, hearing, and red reflex tests, according to sociodemographic variables. National Health Survey, Brazil, 2013.

| Variable | Guthrie test | Hearing test | Red reflex test | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | (95% CI) | p | OR | (95% CI) | p | OR | (95% CI) | p | |

| Regions | |||||||||

| North | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Northeast | 1.79 | (1.25/2.58) | 0.002 | 1.10 | (0.86/1.40) | 0.426 | 0.98 | (0.78/1.24) | 0.911 |

| Southeast | 26.21 | (8.03/85.47) | <0.001 | 7.07 | (5.30/9.43) | <0.001 | 8.68 | (6.55/11.51) | <0.001 |

| South | 20.28 | (6.87/59.86) | <0.001 | 11.78 | (7.60/18.26) | <0.001 | 7.60 | (5.52/10.46) | <0.001 |

| Midwest | 7.70 | (4.36/17.13) | <0.001 | 2.02 | (1.55/2.65) | <0.001 | 1.77 | (1.35/2.32) | <0.001 |

| Skin color/ethnicity | |||||||||

| Black | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.0 | ||||||

| Mixed-race | 0.91 | (0.42/1.97) | 0.827 | 1.06 | (0.74/1.53) | 0.733 | 0.88 | (0.60/1.29) | 0.538 |

| White | 1.87 | (0.82/4.25) | 0.134 | 2.48 | (1.70/3.62) | <0.001 | 2.10 | (1.43/3.08) | <0.001 |

| Private health insurance | |||||||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | |||||

| Yes | 9.20 | (3.80/22.28) | <0.001 | 6.78 | (5.13/8.96) | <0.001 | 5.23 | (4.04/6.77) | <0.001 |

| Income | |||||||||

| 1st quintile | 1.00 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||||

| 2nd quintile | 3.03 | (1.98/4.63) | <0.001 | 1.97 | (1.58/2.46) | <0.001 | 1.83 | (1.47/2.26) | <0.001 |

| 3rd quintile | 8.69 | (4.99/15.14) | <0.001 | 4.78 | (3.68/6.22) | <0.001 | 4.16 | (3.17/5.46) | <0.001 |

| 4th quintile | 10.34 | (4.61/23.17) | <0.001 | 7.45 | (5.01/11.09) | <0.001 | 7.71 | (5.41/11.00) | <0.001 |

| 5th quintile | 12.49 | (3.34/46.74) | <0.001 | 12.35 | (8.03/19.02) | <0.001 | 9.69 | (6.18/15.19) | <0.001 |

OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; p, p-value obtained through logistic regression analysis.

Table 3 shows the results of the multivariate analysis. There was a greater chance of undergoing the Guthrie test in the Southeast, South, Midwest, and Northeast regions, when compared to the North. The same was observed for the newborn hearing screening and the red reflex tests, but there was no statistically significant difference between the North and Northeast regions. Regarding skin color/ethnicity, no differences were observed in the performance of the neonatal screening tests. In all tests, a higher chance of performing the tests was identified among those who reported having private health insurance. Regarding income, there was a significant economic gradient, with the highest rates of neonatal screening test performance observed among the wealthiest individuals. The odds of performing the hearing screening and red reflex test were 3.78 and 3.50 times higher in the wealthiest 20% of individuals when compared to the poorest 20%, except for the Guthrie test.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis for the performance, at any period, of the Guthrie, hearing, and red reflex tests, according to the sociodemographic variables. National Health Survey, Brazil, 2013.

| Variable | Guthrie testa | Hearing testb | Red reflex testc | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | (95% CI) | p | OR | (95% CI) | p | OR | (95% CI) | p | |

| Regions | |||||||||

| North | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Northeast | 1.75 | (1.21/2.53) | 0.003 | 1.09 | (0.85/1.39) | 0.472 | 0.96 | (0.76/1.22) | 0.700 |

| Southeast | 14.56 | (4.34/48.85) | <0.001 | 4.46 | (3.33/5.96) | <0.001 | 5.72 | (4.20/7.78) | <0.001 |

| South | 11.60 | (3.93/34.20) | <0.001 | 7.59 | (4.74/12.14) | <0.001 | 4.71 | (3.29/6.72) | <0.001 |

| Midwest | 5.61 | (2.34/13.47) | <0.001 | 1.34 | (1.01/1.77) | 0.039 | 1.75 | (0.86/1.53) | 0.341 |

| Skin color/ethnicity | |||||||||

| Black | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Mixed-race | 1.15 | (0.52/2.55) | 0.715 | 1.25 | (0.82/1.90) | 0.282 | 0.98 | (0.66/1.44) | 0.923 |

| White | 1.10 | (0.47/2.58) | 0.817 | 1.45 | (0.94/2.24) | 0.084 | 1.21 | (0.82/1.79) | 0.315 |

| Private health insurance | |||||||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.0 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Yes | 2.65 | (1.18/5.93) | 0.018 | 2.98 | (2.19/4.06) | <0.001 | 2.18 | (1.63/2.91) | <0.001 |

| Income | |||||||||

| 1st quintile | 1.00 | 1.0 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 2nd quintile | 2.02 | (1.30/3.15) | 0.002 | 1.32 | (1.04/1.66) | 0.019 | 1.20 | (0.97/1.50) | 0.105 |

| 3rd quintile | 3.70 | (2.01/6.80) | 0.000 | 2.37 | (1.79/3.12) | <0.001 | 2.02 | (1.50/2.71) | <0.001 |

| 4th quintile | 3.35 | (1.42/7.88) | 0.006 | 2.91 | (1.87/4.51) | <0.001 | 3.42 | (2.26/5.17) | <0.001 |

| 5th quintile | 3.18 | (0.94/10.73) | 0.061 | 3.78 | (2.36/6.05) | <0.001 | 3.50 | (2.06/6.10) | <0.001 |

OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; p, p-value obtained through logistic regression analysis.

The present study showed a difference regarding the prevalence of screening test performance, with the proportion of newborns who underwent the Guthrie test being significantly higher than that of the hearing screening and red reflex tests. Inequalities were identified in the performance of the three tests, with the highest prevalence observed among the residents of the South and Southeast regions, of white ethnicity/skin color, whose mothers/guardians had private health insurance, and among the wealthiest individuals. The same inequalities were observed in relation to the performance of the tests within the periods established by the governmental guidelines.

Achieving universal coverage of these tests has been a challenge in Brazil and other countries. In China, the regulation of the neonatal screening program in the country determines the screening of phenylketonuria and congenital hypothyroidism, but the screening of neonatal hearing problems is not yet mandatory. Still, national guidelines have ensured uniform screening through these tests, with high coverage rates, being as high as 99% in some cities.16

Despite the high prevalence of the Guthrie test, a finding also evidenced in the present study, the coverage for the newborn hearing screening can still be considered low when compared to other countries, which recommend its performance in the first weeks of life. In Poland, based on the regulation issued by the Ministry of Health in 2003 on the extension of compulsory hearing screening tests for all newborns, a slight increase in the coverage of this test was obtained from 97.8% in 2004, to 98.4% in 2017.17

In Brazil, when established in 2001, the Neonatal Screening Program included only the Guthrie test.18 More recently, the red reflex and hearing tests were included in these recommendations.4 The performance of the Guthrie test in the Basic Health Units, together with the expansion of primary health care services in the country, might explain the higher prevalence of this test in comparison with the newborn hearing and red reflex tests.19

Also, it should be noted that the differential in knowledge regarding the importance of performing each test may also be an explanatory factor for the higher prevalence of the Guthrie test. A study carried out in the state of Minas Gerais between 2014 and 2015 showed that 98.7% of puerperal women considered the Guthrie test to be important, although only 57% reported receiving information about this test during the prenatal period.20 In contrast, a study carried out in Curitiba between 2013 and 2014 showed that only 30.0% of the puerperal women reported having received information about the neonatal hearing screening test in the prenatal period.20

Regarding the red reflex test, although it is performed before the hospital discharge, inequalities have been observed according to the regions of birth. Thus, classifying it and disseminating its practice as one of the items of the initial physical examination of the newborn still in the maternity ward and/or immediately after, in primary care, could be an alternative to increase its coverage.1,5

Studies evaluating the Neonatal Screening Program had already shown increased coverage of these tests, but their prevalence rates were variable among Brazilian regions.10,21 Still in the Brazilian scenario, the findings of the present study corroborate national research that aimed to analyze the evolution of neonatal screening within the scope of the Brazilian unified health system (Sistema Único de Saúd – SUS) between 2008 and 2011. It was demonstrated that there was an increase in test coverage during the period, but with clear regional differences.11 These inequalities may reflect the financial and structural differences regarding the implementation and maintenance of services that involve the neonatal screening program in the country, from funding, service decentralization, to the provision and training of professionals.21 They may reflect, in short, differences in the organization of the health care network at all levels.12

Neonatal screening coverage has been evaluated in several countries, including Brazil, and it has been demonstrated that the coverage is higher in the states accredited for further testing (congenital hypothyroidism, phenylketonuria, hemoglobinopathies, and cystic fibrosis), with the opposite occurring in those accredited only for congenital hypothyroidism and phenylketonuria screening (values ranging from 47% to 76%), thus reflecting aspects of service provision and organization.21

The performance of the tests within the recommended period was influenced by the skin color/ethnicity, region, having private health insurance, and income, with the greatest differences between the categories being observed for the red reflex and hearing tests, reinforcing the findings that socioeconomic status is associated with access to and use of health services in the country in a timely manner.22,23 Poorer individuals have multiple deprivations, and these are related to high levels of exposure to diseases, inadequate search for healthcare services, and lower probability of receiving effective and timely treatment, including screening tests.23

Although skin color/ethnicity has not shown an association with any of the three outcomes in this study, other studies have shown a predominance of white color/ethnicity regarding the performance of the screening tests, and these racial inequalities have shown to be a challenge for health systems based on principles of equity.24 In the present study, the incorporation of income into the multiple model removed the effect of the outcome association with skin color/ethnicity.

Having a private health insurance was also a factor associated with the performance of the three screening tests, regardless of the per capita family income. A 2018 study by Pilotto et al.,25 conducted between 1998 and 2013, had already shown an increase in the use of medical and dental services, being higher among people with private health insurance. Regarding the neonatal screening tests, a 2016 study by Pinheiro et al.,9 carried out in Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil, in 2010, showed that the difference between the public and private health systems becomes evident when the higher prevalence of the Guthrie test was observed for those born in the private health system network (99.4%) when compared to those born in the public system network (89.6%).

In 2011, Silva et al.22 observed that the demand for health services in Brazil was more frequent among individuals who had private health insurance, demonstrating that having it may reduce the existence of possible financial barriers regarding the access to services, as it also determines a greater use of preventive services. Investment and qualification of the provision of these exams in the SUS scenario are an important strategy in reducing inequalities related to the access to these services, since a strong and effective health system would be able to cover these demands, to meet the objectives proposed by the Ministry of Health aiming for test coverage of 100% of the newborns in the country.

The present study also observed an association between test performance and the mother's/guardian's income, showing that the higher the income quintile, the greater the odds of performing the tests. This result is in agreement with Cavalcanti et al. in 2012,26 who analyzed neonatal hearing screening in the Northeast of Brazil between 2007 and 2009 and identified that the lower prevalence of this test was associated with lower income quintiles, lower maternal schooling, and fewer prenatal consultations. In countries that still show problems related to access to these tests, such as Serbia, Ukraine, and Croatia, a number of impediments have been observed, including poor economic conditions and lack of government support, along with cultural differences, as well as large geographical variations.21

According to the IBGE in 2016,27 the demand for health care varies according to income, and the demand for health care in those with the highest income quintile is higher. Also, overall, individuals with higher income have a higher level of schooling. These data could justify the higher proportion of screening tests performed by the higher income population, associated with the fact that a higher level of education can contribute to the awareness of the importance of performing these tests.28I.e., this population group has more knowledge about the test benefits, better economic prospects to perform them (whether to go to a health facility or to use them in the private health system), and potentially reside in places with greater access to health services.

Neonatal screening tests, when carried out in the recommended period, have the capacity to identify the target diseases in newborns, still in the pre-symptomatic phase, and allow early intervention, prevention of manifestations, and monitoring of the child's health; their benefits have already been elucidated in the literature.29 Although these tests are offered by SUS, the lack of professionals, lack of service structure,20 and follow-up problems in the prenatal and immediate postnatal periods are suggested as possible causes for not performing these tests during the recommended period.

As study limitations, the authors emphasize that the PNS is a cross-sectional survey and uses self-reported information. To investigate the screening tests, the information was provided by the mother and/or guardian, which allows errors to occur due to memory bias. Also, the question about having a private health insurance was related to the time of the interview, which may differ from what occurred at the time when the tests were to be performed, which could overestimate or underestimate the information. However, it is necessary to consider the importance of periodic population-based surveys that reflect the health reality of the country. The PNS is one of the largest home-based surveys at the national level, it is carried out with recognized methodological rigor, and the exploration of data from this survey provides a current and contextualized analysis of the investigated outcomes.

This study showed that the region, having private health insurance, and income were factors associated with the performance of the Guthrie, hearing, and red reflex tests in Brazil, demonstrating there are inequalities in the performance of neonatal screening tests in the country. Therefore, intersectoral policies must be planned and implemented to promote articulation and coordination between the different governmental sectors, in which the health, education, economic, and social areas can guarantee, together, a good structure for the services and integral care provided to the newborn/child.

The Brazilian Neonatal Screening Program is a large-scale program and stands out for its inclusion in SUS. Nevertheless, achieving higher levels of coverage and access to these tests in the country remains a challenge, especially regarding organization and logistics. In addition to the country's size and the decentralization of services, the national economic development and low per capita public spending on health also have an impact, as these actions must be recognized as important factors for the reduction of newborn and child mortality.

SUS is a system based on the concept of citizenship that establishes universal and integral access to health care. Therefore, ensuring these tests are performed in a universal and public system should promote equity and access to screening for all newborns; however, inequalities regarding access to these services are reflected in other gaps in healthcare supply. Promoting basic health care, good quality prenatal care and the SUS itself are measures to increase access to the tests and reduce the existing inequalities.

In this sense, it is suggested that new studies be developed with the objective of contributing to the organization and increase of the offer of these services in the country, identifying factors that modulate access to the tests and means of overcoming the described impediments.

FundingConselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico – CNPq – Brazil through a scholarship from Programa Institucional de Bolsas de Iniciação Científica – PIBIC – 2016/2017 awarded to Mariana Borsa Mallmann, according to Public Notice PIBIC/CNPq – PIBIC-Af/CNPq – BIPI/UFSC 2016/2017.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Mallmann MB, Tomasi YT, Boing AF. Neonatal screening tests in Brazil: prevalence rates and regional and socioeconomic inequalities. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2020;96:487–94.