To evaluate the maternal perceptions and attitudes related to adherence to healthcare professionals’ guidelines on breastfeeding and complementary feeding, and associated factors.

MethodsA cross-sectional analysis of data from a randomized field trial was performed, in which 20 health centers (HCs) were selected in the city of Porto Alegre, state of Rio Grande do Sul, from eight Health Management Districts of the city. Pregnant women were selected from these HCs, and when the children were aged between six and nine months, data regarding the maternal perception of adherence to professional advice and consequences of feeding practices on child health were obtained during home visits. Association analyses were performed using Poisson regression.

ResultsData were collected from 631 mother-child binomials. According to the mothers’ perception, 47% reported not following instructions received in the HU. Among these, 45.7% did not recognize the importance of eating habits for the child's health. The perception of adherence to professional advice was associated with higher prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding (EBF), introduction of solid food (ISF) after four months, introduction of non-recommended foods after six months, and higher family income. A higher prevalence of EBF and ISF was observed after four months (p < 0.05) among mothers who believed in the importance of feeding habits for the child's health.

ConclusionThere was a high prevalence of mothers who did not follow the advice of health professionals; the perception that food does not affect the child's health can be a barrier to the improvement of eating habits in childhood.

Avaliar a percepção e as atitudes maternas relacionadas à adesão às orientações de profissionais de saúde sobre aleitamento materno e alimentação complementar e fatores associados.

MétodosAnálise transversal de dados de ensaio de campo randomizado, em que foram sorteadas 20 Unidades de Saúde (US) de Porto Alegre-RS das oito gerências distritais de saúde do município. Gestantes atendidas nestas US foram selecionadas e, aos 6-9 meses de idade das crianças, foram obtidos, em visitas domiciliares, dados quanto à percepção materna de adesão às orientações dos profissionais e de consequências das práticas alimentares na saúde da criança. Análises de associação foram realizadas por meio de Regressão de Poisson.

ResultadosForam obtidos dados de 631 binômios mãe-criança. Conforme a percepção das mães, 47% relataram não seguir orientações recebidas nas US. Dentre essas, 45,7% não reconhecem a importância da alimentação para a saúde da criança. A percepção de adesão às orientações dos profissionais foi associada com maiores prevalências de aleitamento materno exclusivo (AME), introdução de alimentos sólidos (IAS) após quatro meses e introdução de alimentos não recomendados após seis meses, além de maior renda familiar. Observaram-se maiores prevalências de AME e IAS após quatro meses (p<0,05) entre as mães que acreditam na importância da alimentação para a saúde da criança.

ConclusãoHouve elevada prevalência de mães que não seguem as orientações dos profissionais de saúde e a percepção de que a alimentação não influencia a saúde da criança pode ser uma barreira para melhorias nas práticas alimentares na infância.

Dietary guidelines for children under two years recommend exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) until the sixth month of life and complementary feeding after this age in order to ensure proper growth and development and to prevent morbidities, especially iron-deficiency anemia.1,2 In Brazil, data from the Second Survey on the Prevalence of Breastfeeding in Brazilian Capitals3 demonstrated that half of the children had EBF for 54.1 days or less. Furthermore, the introduction of other foods in the child's diet proved to be inadequate: approximately 18% of children consumed liquids such as teas, juices, and other types of milk in the first month of life; 21% consumed salty foods between three and six months of age; and 8.9% consumed non-recommended foods such as cookies and snacks at ages between three and six months 46.4% between six and nine months, and 71.7% between nine and 12 months.3

The reasons related to weaning and early introduction of foods are many; socioeconomic and demographic factors,4–7 psychological and behavioral characteristics of the mother and the family,6,8 and factors related to the health professional9–12 should be highlighted. Among the determinants related to the healthcare professionals and their guidelines, the lack of information from professionals,13 the difficulties in communication between the professional and postpartum women,10 the mother's personal divergences regarding the dietary guidelines received,14 and the maternal belief that feeding practices have little influence on child development must be emphasized.15 Intervention studies on breastfeeding (BF) and complementary feeding in different populations concluded that there are barriers in several areas that can influence maternal nonadherence to healthcare professionals’ guidelines.16–18 Considering this evidence, this study aimed to evaluate the maternal perceptions and attitudes regarding adherence to healthcare professionals’ guidelines on BF practices and complementary feeding, and associated factors.

MethodsThis was a cross-sectional analysis of data collected between April of 2008 and March of 2010, in a cluster-randomized field trial. Participants were women in the third trimester of the pregnancy, treated at 20 health centers (HCs) in the city of Porto Alegre, as well as the infants born to these mothers. The sample size calculation was performed for the primary purpose of the larger study: to assess the impact of healthcare professionals’ training on the feeding practices in the first two years of a child's life. Consequently, 720 pregnant women were included in the study, distributed between intervention and control groups.

The selection of the HCs participating in the study considered as eligible those that had attended to children under 1 year of age over 100 times in 2006 and that did not participate in the Family Health Strategy or maintain partnerships with other health, education, or business institutions at the beginning of the study. Of the 56 HCs of the municipality, 31 were eligible. The names of eligible HCs were inserted in a black envelope and, for each of the eight health management districts, two HCs were drawn: one would be the intervention group that would receive healthcare professionals’ intervention as part of the the governmental program “Ten steps for healthy feeding for Brazilian children from birth to 2 years of age”,19 and the other would be the control group, which would follow their routine without intervention from the research group. Four additional HCs were selected for the two groups in order to achieve the previously planned sample size of 20 HCs.

The data collection team consisted of previously trained undergraduate and graduate students of Nutrition. This team identified pregnant women in the last trimester of pregnancy among patients of the participating HCs, and invited them to participate in the study. After reading and signing the informed consent form, the mothers answered a questionnaire regarding their age, level of education, occupation, parity, marital status and family income, probable date of delivery, and address and telephone contact for posterior home visits. Human immunodeficiency virus-positive pregnant women were excluded from the study.

The second phase of data collection occurred during home visits between six and nine months after the expected date of delivery. During these visits, the mothers answered a structured questionnaire regarding BF and introduction of other foods in the children's diet, as well as their perceptions and attitudes towards healthcare professionals’ guidelines on the child's dietary habits. BF was classified as EBF when the child received only breast milk, with no water, tea, juice, other types of milk, or other foods, and as BF when the child received breast milk, with or without other types of food according to the definitions of the World Health Organization (WHO).20 The introduction of foods in the child's diet was analyzed in relation to the introduction of solid foods and non-recommended foods, specifically honey, coffee, processed soups, chocolate, artificial juices, soft drinks, cream-filled biscuits, cookies, “petit suisse” cheese, processed meats, chocolates, candies, snacks, jello, ice cream, and fried foods.

Maternal attitudes regarding the healthcare professionals’ guidelines were investigated through closed questions developed specifically for this study. Regarding the perception of adherence to healthcare professionals’ guidelines regarding the feeding of infants, the mothers answered the following question (Q1): “Do you think you accurately follow the appropriate recommendations on BF and infant feeding?” The answer to this question was classified into two categories: 1 - follows the guidelines, 2 - does not follow the guidelines.

Mothers who reported not following the guidelines answered an additional question (Q2), with five alternative answers: “Thus, you do not accurately follow the recommendations on BF and infant feeding, however: (1) you are sure that what he/she eats does not harm his/her health; (2) you worry that what he/she eats can cause him/her any problem; (3) you think you should change his/her diet, so that he/she eats healthy foods; (4) you already know what you have to do to change this situation; (5) you are already changing it for the better.” For the statistical analyses of these outcomes, the mothers were grouped as: A) has no perception of the influence of food on the child's health (mothers who chose option 1 in question Q2) and B) have the perception that food can influence the child's health (mothers who chose options 2-5 in response to question Q2).

Data were entered in duplicate using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) release 16.0, and validated using Epi Info, release 6.4. Maternal and family characteristics were categorized, and their association with maternal perception of adherence to healthcare professionals’ guidelines was assessed by the chi-squared test. Characteristics with p ≤ 0.20 in the crude analysis were tested in the multiple model study using Poisson regression with robust estimate. The magnitude of the associations between feeding practices and maternal perception (a) of having followed the healthcare professionals’ guidelines and (b) of considering feeding habits important for the child's health were estimated using prevalence ratios and their 95% confidence intervals (95% CI).

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Universidade Federal de Ciências da Saúde de Porto Alegre under protocol No. 471/07, and by the Ethics Committee of the Health Department of Porto Alegre.

ResultsIn the first phase of data collection, 715 pregnant women were interviewed. When the children were aged between six and nine months, 29 mothers refused to continue participating in the study, 11 moved to another city, eight were excluded due to illness or death of the mother or child; 14 children were excluded due to congenital malformations, and 22 mother-child pairs were not found, resulting in a sample size of 631.

Data from the intervention and control groups were used together in the present study, as there was no statistical difference between the groups regarding maternal perception of adherence to healthcare professionals’ guidelines, the main outcome of this study. Among the participants, 20.9% were younger than 20 years, 46.9% had eight years or less of schooling, 68% did not work outside of the home, 22.3% were living without a partner, 55.5% already had other children, 52.3% were overweight, and 47.7% of households had a monthly income of up to two Brazilian minimum wages.

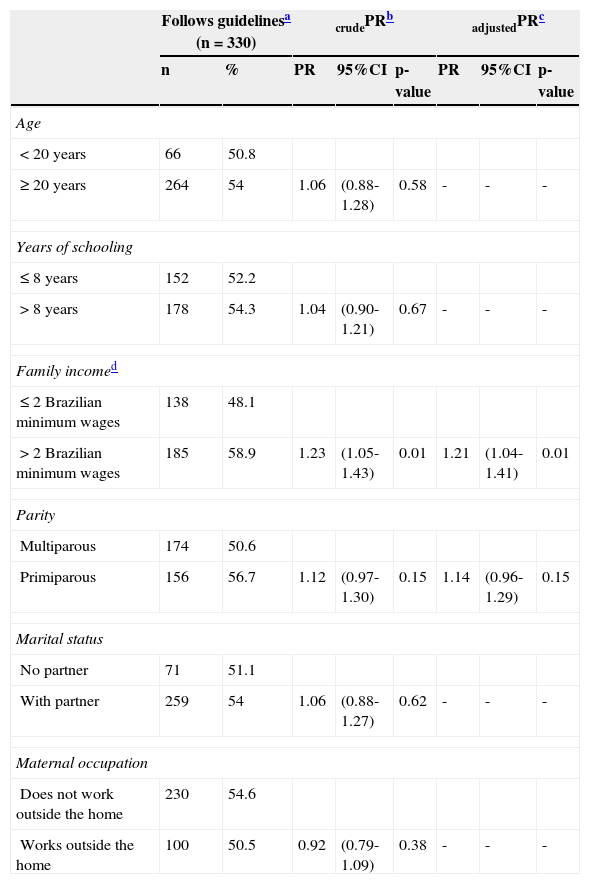

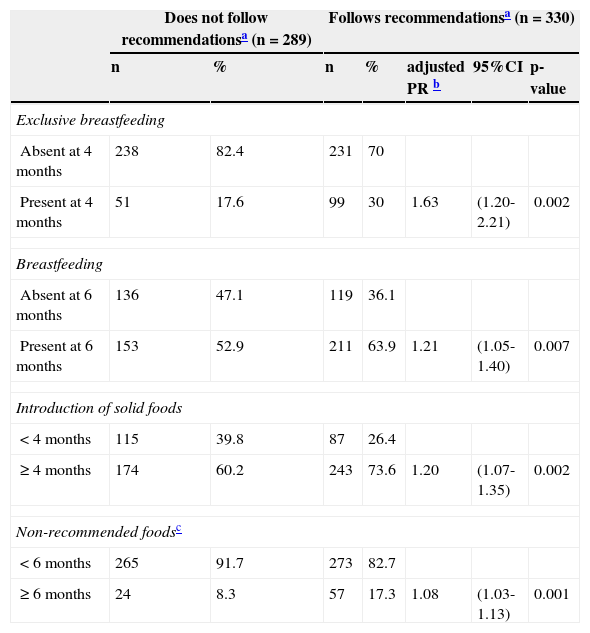

The HC healthcare professionals’ guidelines for feeding children were reportedly followed by 55% of the mothers (330/619). The multivariate Poisson regression suggests that the prevalence of mothers that adhered to healthcare professionals’ guidelines was higher among those who had a family income above two Brazilian minimum wages (p = 0.01), with no evidence of association between adherence to dietary guidelines and other maternal and family characteristics (Table 1). The multivariate Poisson regression also showed that the prevalence of maternal perception of adherence to dietary guidelines was higher when the child received EBF at four months of age and BF at six months, when the introduction of solid foods occurred after four months of age, and when the consumption of non-recommended food occurred after six months, after adjusting for total household income (Table 2).

Association between maternal and family characteristics and the perception of adherence to healthcare professional's dietary guidelines (n = 619).

| Follows guidelinesa (n = 330) | crudePRb | adjustedPRc | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | PR | 95%CI | p-value | PR | 95%CI | p-value | |

| Age | ||||||||

| < 20 years | 66 | 50.8 | ||||||

| ≥ 20 years | 264 | 54 | 1.06 | (0.88-1.28) | 0.58 | - | - | - |

| Years of schooling | ||||||||

| ≤ 8 years | 152 | 52.2 | ||||||

| > 8 years | 178 | 54.3 | 1.04 | (0.90-1.21) | 0.67 | - | - | - |

| Family incomed | ||||||||

| ≤ 2 Brazilian minimum wages | 138 | 48.1 | ||||||

| > 2 Brazilian minimum wages | 185 | 58.9 | 1.23 | (1.05-1.43) | 0.01 | 1.21 | (1.04-1.41) | 0.01 |

| Parity | ||||||||

| Multiparous | 174 | 50.6 | ||||||

| Primiparous | 156 | 56.7 | 1.12 | (0.97-1.30) | 0.15 | 1.14 | (0.96-1.29) | 0.15 |

| Marital status | ||||||||

| No partner | 71 | 51.1 | ||||||

| With partner | 259 | 54 | 1.06 | (0.88-1.27) | 0.62 | - | - | - |

| Maternal occupation | ||||||||

| Does not work outside the home | 230 | 54.6 | ||||||

| Works outside the home | 100 | 50.5 | 0.92 | (0.79-1.09) | 0.38 | - | - | - |

95% CI, 95% confidence interval; PR, prevalence ratio.

Dietary practices during the children's first year of life according to the maternal perception of adherence to healthcare professionals’ recommendations (n=619).

| Does not follow recommendationsa (n = 289) | Follows recommendationsa (n = 330) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | adjusted PR b | 95%CI | p-value | |

| Exclusive breastfeeding | |||||||

| Absent at 4 months | 238 | 82.4 | 231 | 70 | |||

| Present at 4 months | 51 | 17.6 | 99 | 30 | 1.63 | (1.20-2.21) | 0.002 |

| Breastfeeding | |||||||

| Absent at 6 months | 136 | 47.1 | 119 | 36.1 | |||

| Present at 6 months | 153 | 52.9 | 211 | 63.9 | 1.21 | (1.05-1.40) | 0.007 |

| Introduction of solid foods | |||||||

| < 4 months | 115 | 39.8 | 87 | 26.4 | |||

| ≥ 4 months | 174 | 60.2 | 243 | 73.6 | 1.20 | (1.07-1.35) | 0.002 |

| Non-recommended foodsc | |||||||

| < 6 months | 265 | 91.7 | 273 | 82.7 | |||

| ≥ 6 months | 24 | 8.3 | 57 | 17.3 | 1.08 | (1.03-1.13) | 0.001 |

95% CI, 95% confidence interval; PR, prevalence ratio.

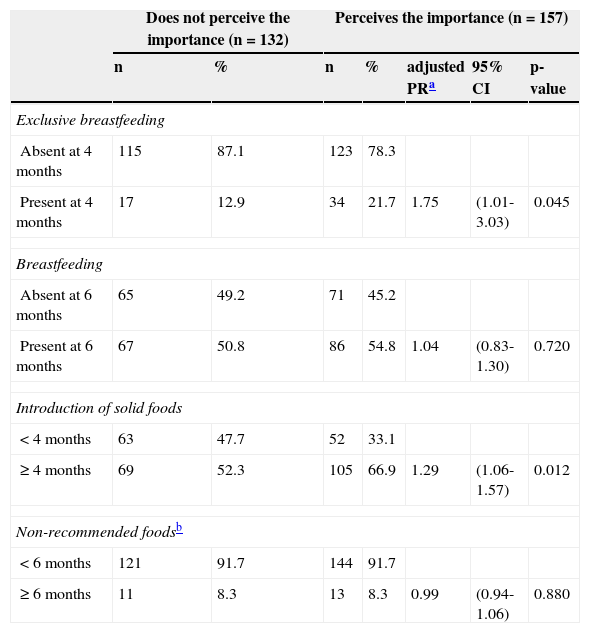

When data from the mothers who reported not following the healthcare professionals’ guidelines were analyzed separately, it was observed that 54% (157/289) of them acknowledged the influence of food on the child's health. The maternal perception of the importance of nutrition for the child's health was associated with healthy eating habits in the first year of the child's life (p < 0.05). There was a higher prevalence of EBF at four months of age and solid foods introduced after four months of age among mothers who perceived that dietary habits influenced the child's health (Table 3).

Dietary practices during the children's first year of life according to the maternal perception of the importance of nutrition for the child's health, among mothers who reported not following the recommendations of healthcare professionals (n = 289).

| Does not perceive the importance (n = 132) | Perceives the importance (n = 157) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | adjusted PRa | 95% CI | p-value | |

| Exclusive breastfeeding | |||||||

| Absent at 4 months | 115 | 87.1 | 123 | 78.3 | |||

| Present at 4 months | 17 | 12.9 | 34 | 21.7 | 1.75 | (1.01-3.03) | 0.045 |

| Breastfeeding | |||||||

| Absent at 6 months | 65 | 49.2 | 71 | 45.2 | |||

| Present at 6 months | 67 | 50.8 | 86 | 54.8 | 1.04 | (0.83-1.30) | 0.720 |

| Introduction of solid foods | |||||||

| < 4 months | 63 | 47.7 | 52 | 33.1 | |||

| ≥ 4 months | 69 | 52.3 | 105 | 66.9 | 1.29 | (1.06-1.57) | 0.012 |

| Non-recommended foodsb | |||||||

| < 6 months | 121 | 91.7 | 144 | 91.7 | |||

| ≥ 6 months | 11 | 8.3 | 13 | 8.3 | 0.99 | (0.94-1.06) | 0.880 |

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; PR, prevalence ratio.

This study was performed aiming to understand the maternal perception and attitudes related to healthcare professionals’ guidelines regarding feeding practices in the first year of life. According to the results, approximately 50% of mothers stated they did not follow the guidelines. Other studies with the same object of investigation concluded that the mother's decision regarding the type of food to be offered to the infant is strongly influenced by the partner, family, or friends, and that perhaps healthcare professionals are not properly training regarding the child's feeding habits or beliefs regarding the subject.9,10,21,22 These results suggest that the transmission of information alone is not enough to motivate or to determine the actions of mothers regarding the child's dietary practices. However, an intervention study with healthcare professionals showed that motivational interviewing techniques increased patient adherence to treatment,23 suggesting that the healthcare professionals’ communication strategy in primary care can be a tool to improve maternal adherence to guidelines on the feeding practices of their children.

Among the maternal and family characteristics analyzed in this study, family income was the only variable associated with the group of mothers who reported following the healthcare professionals’ guidelines. Several studies that investigated the socioeconomic and demographic factors associated with adherence to healthy eating habits early in life demonstrated associations between adherence and maternal characteristics such as age, education, income, and maternal occupation, but the results differ among the studies, perhaps due to differences among the studied populations.5,12,13,21,24–26

The highest prevalence of recommended practices of BF and complementary feeding were observed among mothers who followed the healthcare professionals’ guidelines and among those who reported not following the guidelines, but showed concern or consideration regarding the child's dietary habits. These results confirm the consistency of maternal responses regarding their perception, and suggest that, in the context of primary health care in which this population is treated, adherence to health professional guidelines imply in a positive impact on the feeding behavior of this group, in particular. Furthermore, the best dietary practices were observed when the mother perceived that food was important for the child's health, which is in agreement with studies that indicate greater effectiveness in intervention programs focused on maternal beliefs, attitudes, and subjective norms, covering interactive discussions, preferably with the presence of the family, aiming to prevent possible difficulties and focusing on variables that may be modifiable.9,14,27–29

Regarding the limitations of the present study, the lack of data on the frequency and quality of dietary guidelines provided by healthcare professionals to the mothers must be highlighted. Moreover, the mothers’ responses regarding their perception of whether or not they followed healthcare professionals’ guidelines may have been biased in relation to other sources of information on this subject. Another limitation may be based on the mother's predisposition to respond positively regarding their adherence to dietary practices recommended by healthcare professionals for fear of being judged by the interviewer. This, however, reflects the possibility that the prevalence of mothers who do not follow the healthcare professionals’ guidelines may be even higher than that observed in this study.

Based on the present results, a high prevalence of mothers who reported not following primary healthcare health professionals’ guidelines was observed, as well as a large percentage of mothers who did not associate feeding practices in the first year of life with health outcomes for the child. Perhaps the lack of understanding of the importance of nutrition for healthy growth and development is a barrier to maternal adherence to healthcare professionals’ guidelines and, as suggested by another study, the inclusion of more information on the importance of nutrition in the first year of life during routine visits30 may be an effective tool for better maternal adherence to these recommendations. The need for qualitative studies that investigate maternal perceptions, beliefs, and attitudes in relation to their children's early dietary habits is emphasized.

FundingFundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul (FAPERGS).

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Broilo MC, Louzada ML, Drachler MdL, Stenzel LM, Vitolo MR. Maternal perception and attitudes regarding healthcare professionals’ guidelines on feeding practices in the child's first year of life. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2013;89:485–91.