To analyze the association between the degree of compliance with the ten steps of the Breastfeeding-Friendly Primary Care Initiative (BFPCI) and the prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) in infants younger than six months in the city of Rio de Janeiro.

MethodsThis was a cross-sectional study conducted in a representative sample of 56 primary health care units of this municipality. The assessment of compliance with the ten steps of the BFPCI was carried out by interviewing health care professionals, pregnant women, and mothers; the generated performance scores were classified into tertiles. To obtain the outcome, i.e., the EBF, a data collection questionnaire was applied to mothers of children younger than six months who were followed up at these units in November of 2007. Prevalence ratios were obtained for the EBF using Poisson regression with robust variance.

ResultsThe prevalence of EBF was 47.6%. In the multivariate analysis, the upper tertile of performance showed a 34% higher prevalence of EBF (PR=1.34, 95% CI: 1.24 to 1.44) and the second tertile was 17% higher (PR=1.17, 95% CI: 1.08 to 1.27) than the first tertile. Mothers who did not work outside home had a 75% higher prevalence of EBF (PR=1.75, 95% CI: 1.53 to 2.01); assistance in a basic health unit, as opposed to a family health unit, implied a 10% higher prevalence (PR=1.10, 95% CI: 1.03 to 1.19). The prevalence of EBF decreased 1% for each day of the infant's life (PR=0.993, 95% CI: 0.992 to 0.993).

ConclusionGiven the contribution of BFPCI to the practice of EBF, a greater investment in the expansion and sustainability of this initiative is recommended, as well as its association with other strategies to promote, protect, and support breastfeeding.

Analisar a associação entre o grau de cumprimento dos Dez Passos da Iniciativa Unidade Básica Amiga da Amamentação (IUBAAM) e a prevalência de aleitamento materno exclusivo (AME) em menores de seis meses no município do Rio de Janeiro.

MétodosEstudo transversal conduzido em amostra representativa de 56 unidades básicas de saúde deste município. A avaliação do grau de cumprimento dos Dez Passos da IUBAAM foi realizada por entrevista a profissionais, gestantes e mães, e os escores de desempenho gerados foram classificados em tercis. Para obtenção do desfecho, o AME, foi aplicado formulário de coleta de dados às mães de crianças menores de seis meses que demandaram estas unidades em novembro de 2007. Foram obtidas razões de prevalência do AME por regressão de Poisson com variância robusta.

ResultadosA prevalência de AME foi de 47,6%. Na análise multivariada, o tercil superior de desempenho apresentou uma prevalência de AME 34% maior (RP=1,34; IC95% 1,24-1,44), e o segundo tercil, 17% maior (RP=1,17; IC95% 1,08-1,27) que o inferior. A mãe não trabalhar fora gerou uma prevalência de AME superior em 75% (RP=1,75; IC95% 1,53-2,01), e a assistência em unidade básica de saúde, em contraposição à saúde da família, em 10% (RP=1,10; IC95% 1,03-1,19). A prevalência de AME caiu 1% a cada dia a mais do bebê (RP=0,993; IC95%: 0,992-0,993).

ConclusãoDiante da contribuição da IUBAAM à prática do AME, recomenda-se maior investimento na expansão e sustentabilidade desta iniciativa, bem como sua articulação com outras estratégias de promoção, proteção e apoio à amamentação.

There is extensive evidence on the benefits of breastfeeding for the mother's health and for the healthy growth and development of the child.1 Exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) has an even greater impact on the prevention of morbidity and mortality, particularly regarding its effect in reducing gastrointestinal tract infections.2

In 1981, the National Breastfeeding Implementation Programme was established in Brazil, developing coordinated actions for the reduction of early weaning. In the 1990s, the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Fund for Children (UNICEF) proposed strategies to encourage the establishment of routines favorable to breastfeeding in maternity wards.3

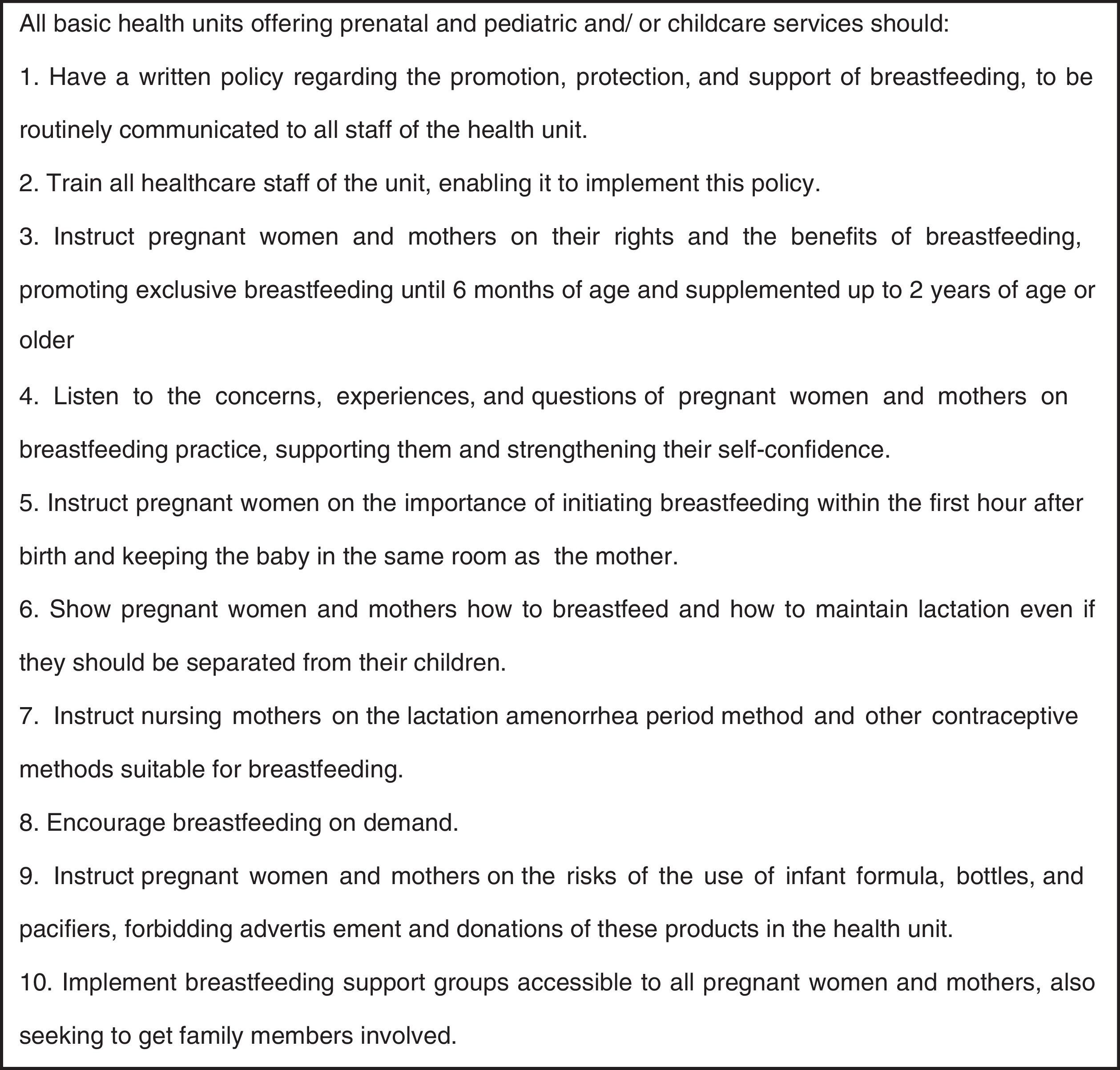

In order to engage primary care in promoting, protecting, and supporting breastfeeding, in 1999 the State Health Secretariat of Rio de Janeiro launched the Breastfeeding-Friendly Primary Care Initiative (BFPCI).4 This initiative was the result of a systematic review which provided evidence on actions developed in primary care that showed to be effective in extending EBF duration.5 The BFPCI advocates the implementation of the “ten steps to successful of the BHUBFI.” The first two steps refer to the structure the unit must have for its performance, and the others refer to the process of guidance on breastfeeding management and support given to pregnant women and mothers for this practice6 (Fig. 1).

Since 2000, the Health and Civil Defense Secretariat of Rio de Janeiro (RJ-SMSDC) has been investing in the organization of BFPCI in primary health care services in order to maximize opportunities to promote and support breastfeeding in pre-natal care and to mother-child pairs. Since 2003, the health teams have been trained in 24-hour courses of BHUBFI, which include clinical management and individual and group counseling on breastfeeding; regional health coordinators accompany the entire accreditation process.7

In the period from 2003 to 2012, 208 courses were given on this initiative and 5,155 health professionals were trained. Nearly the entire primary care network has professionals who have attended the 24-hour courses of BFPCI, which has contributed to breastfeeding promotion in the municipality of Rio de Janeiro. In this municipality, of the 195 primary units in the health care network, 19 have received the title of the Breastfeeding-Friendly Basic Health Unit, which represents 22% of the 87 units accredited by the BFPCI in the state.8

These strategies developed in the primary and hospital network are generating positive results, such as the increase observed in Rio de Janeiro in the prevalence of EBF among children younger than 6 months: from 13.8% in 1996 to 33.3% in 2006.9 However, the six-month EBF recommended by the WHO is still far from reality.10

Despite the quantitative development regarding the number of health units accredited in BFPCI and the prevalence of EBF in the city of Rio de Janeiro, it was not known to what extent the primary health network was involved with this initiative, or to what extent this initiative contributed to the practice of EBF. This article aimed to analyze the association between the degree of compliance with the ten steps of the BFPCI in the city of Rio de Janeiro and the prevalence of EBF in children younger than 6 months followed up at the primary health care network in this city.

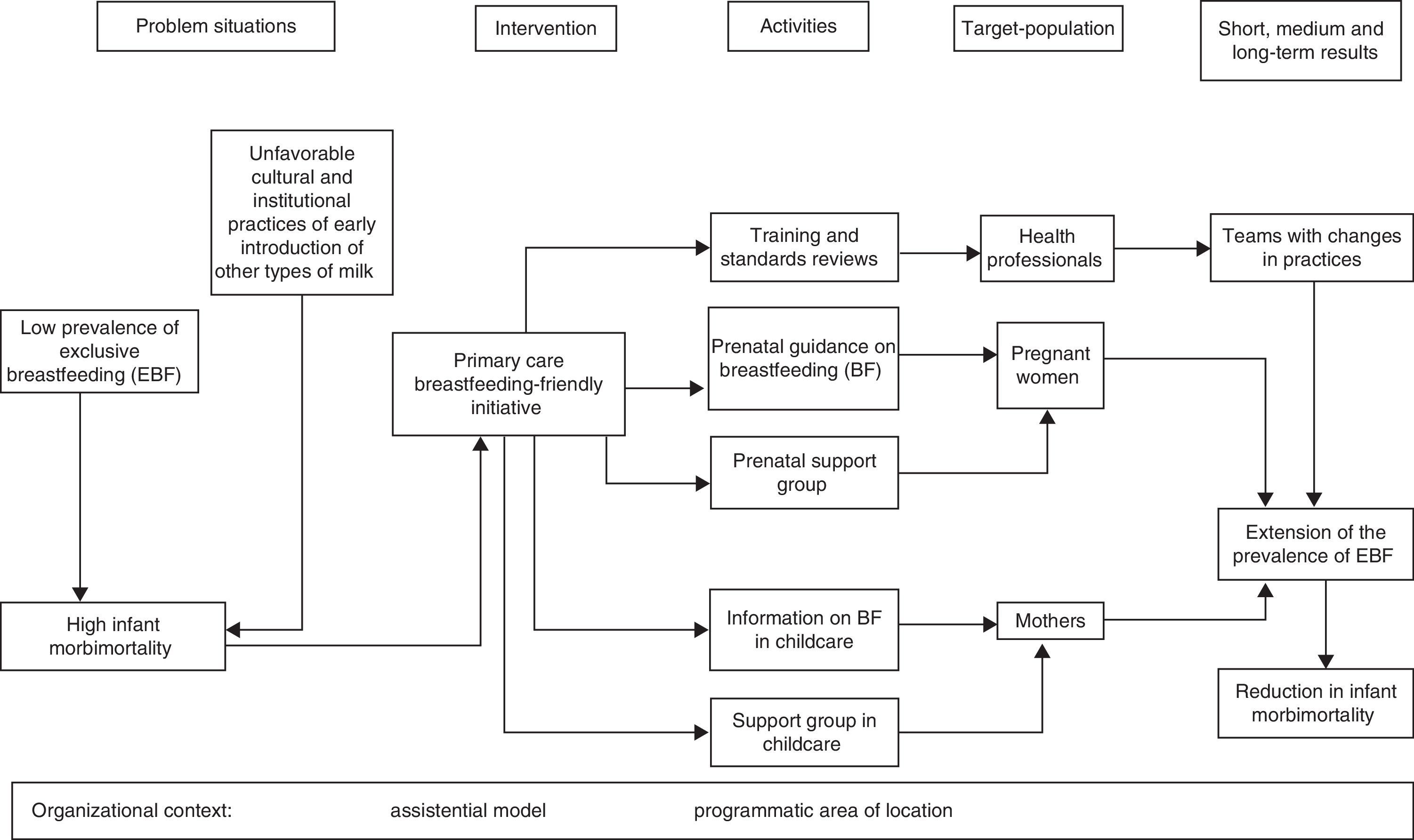

MethodsThis was a cross-sectional type 2 implementation analysis, which correlated the variations in the implementation of an intervention (the degree of compliance with the ten steps of the BFPCI) and the observed results (EBF prevalence).11 An evaluation theoretical model (Fig. 2) was developed that addresses the problem situations that led to the creation of the BFPCI intervention, the activities developed in the primary care units on the target populations, and the short-, medium-, and long-term results. This model also included intervening variables related to the organizational context: the model of assistance and location of the unit by planning area.

This evaluation study was conducted between October of 2007 and May of 2008. A random sample of primary care units, stratified by city districts (the 10 planning areas [PA]) and unit profiles, was studied. This profile was defined considering the model of assistance and the demand for prenatal care of the unit. The median monthly number of prenatal consultations undertaken in these units in the first half of 2007 was used as a criterion for classification of this demand. Based on these parameters, three categories were created: basic units with demand for prenatal care above the median (> 162 consultations), basic units with demand for prenatal care below the median (≤ 162), and family health units (family health centers/community agent health program – Postos de Saúde da Família/Programa de Agentes Comunitários em Saúde [PSF/PACS]). At the time of the study, this network consisted of 152 units: 79 basic units (38 with demand for prenatal care above the median and 41 with demand below the median) and 73 family health units.

The drawing of the random sample of health facilities was based on the registration of units for the year 2007 and considered the proportion of health units according to the PA and unit profiles (composition between model of assistance and prenatal demand). The sampling plan employed resulted in a sample of 56 units, with an oversample of 3%, considering possible losses, totaling 58 units. This size would be capable of estimating the mean of the variable of interest (performance score of BFPCI implementation) with maximum acceptable error of 5% at a confidence level of 95%, assuming that the center of the proposed scale (i.e., five) would be the expected value (mean) of the score, and that 1.2 would be the standard deviation of this mean, as these values were not previously known.12

The accreditation evaluation method was used for the construction of the performance score of BFPCI implementation.13 Compliance with the ten steps of the BFPCI was assessed by verifying compliance with the parameters, as a number ranging from 2 to 11 per step, comprising in total 55 parameters. These parameters were scored as inversely proportional to the number of parameters for each step, with the score for each step varying from 0 to 1 point, yielding a final score that could range from 0 to 10 points. The assessment tools were applied in each unit by two accredited assessors who were not in the PA, under the supervision of the first author of this article. These tools consisted of structured questionnaires to interview the manager of the unit, the health professionals, pregnant women, and mothers, as well as forms for reviewing the written norms and routines, and observation of antenatal and pediatric services.

The evaluation of the structure was performed by applying the aforementioned forms and interviewing the unit manager and ten members of the healthcare team, from different professional categories, randomly selected. The evaluation process included the interview of ten pregnant women and ten mothers of children younger than 1 year, randomly selected among the patients assisted by the unit on evaluation days. Inclusion criteria for members of the healthcare team included working with the mother-child pair and working in the unit for at least six months. The mother and child should have been attended to at the unit at least twice.

To evaluate the outcome, i.e., the prevalence of EBF, a data collection form was applied in the weighing room of 56 sampled units, to all mothers of children younger than 6 months who came to these units during the month of November of 2007. Previously trained professionals working in the weighing room routine filled this form, recording the number in the child's records and asking the mothers the child's date of birth, the current feeding status of the infant, whether they worked outside the home, and whether they had received support for breastfeeding from the maternity ward staff.

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Municipal Secretariat of Health and Civil Defense of Rio de Janeiro, Edict 158A/2007. The interviews for the evaluation of the structure and process were performed after the signing of an informed consent; the form for data collection was applied in the weighing room after verbal consent.

Data from the questionnaires were entered into the Epi-date software. The generated performance scores with the scores of 55 parameters included in the assessment of compliance to ten steps of the BFPCI13 were classified into tertiles: upper, intermediate, and lower.

EBF was considered as the outcome. The categorization of the type of feeding given to the child followed the WHO parameters;14 EBF was defined as when the child received only breast milk or expressed human milk, but also could be receiving vitamins, mineral supplements, or medications.

A bivariate analysis was initially developed between each exposure variable and outcome (Table 1). The following exposure variables were considered: 1. performance score (in tertiles); 2. model of assistance (basic health unit vs. family unit); 3. help from the maternity ward staff (yes vs. no); 4. maternal employment (yes vs. no); 5. child's age (younger than 3 months vs. 3 to 6 months). Chi-squared hypothesis tests were performed and crude prevalence ratios (PR) were obtained with their respective 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Exposure variables that in the bivariate analysis were associated with the outcome with p-value less than or equal to 20% in the chi-squared test were selected for the multivariate analysis.

Prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding according to the performance score, type of unit, help received from the hospital staff when breastfeeding, maternal employment and child's age. Municipality of Rio de Janeiro, 2007.

| Frequency | Exclusive breastfeeding | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | Nn | % | Crude PR | p-value | |

| Performance score | ||||||

| Upper tertile (> 6.010) | 1,233 | 30.1 | 684 | 55.5 | 1.387 | < 0.001 |

| Intermediate tertile (4.602-6.010) | 1,476 | 36.1 | 711 | 48.2 | 1.205 | < 0.001 |

| Lower tertile (< 4.602) | 1,383 | 33.8 | 553 | 40.0 | 1 | |

| Assistance model | ||||||

| Basic health unit | 3,024 | 73.9 | 1487 | 49.2 | 1.139 | 0.001 |

| Family health unit | 1,068 | 26.1 | 461 | 43.2 | 1 | |

| Help from hospital staff | ||||||

| No | 756 | 18.5 | 372 | 49.2 | 1.042 | 0.323 |

| Yes | 3,336 | 81.5 | 1576 | 47.2 | 1 | |

| Maternal employment | ||||||

| No | 3,497 | 85.5 | 1803 | 51.6 | 2.116 | < 0.001 |

| Yes | 595 | 14.5 | 145 | 24.4 | 1 | |

| Child's age | ||||||

| < 3 months | 2,125 | 51.9 | 1318 | 62.0 | 1.937 | < 0.001 |

| 3 months to < 6 months | 1,967 | 48.1 | 630 | 32.0 | 1 | |

PR, prevalence ratio.

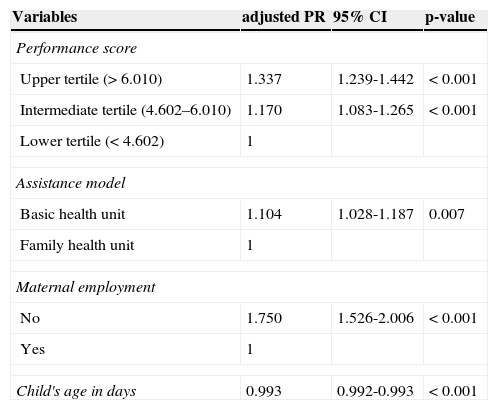

The final model used to estimate measures of association, with their respective 95% CIs, consisted of the exposure variables that had a p-value less than or equal to 5%, and the child's age was analyzed as a continuous variable (Table 2). The adjusted prevalence ratios were obtained by Poisson regression with robust variance, as the outcome showed a high prevalence.15

Adjusted prevalence ratio (PR) of exclusive breastfeeding in children younger than 6 months followed at the primary care network. Municipality of Rio de Janeiro, 2007.

| Variables | adjusted PR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Performance score | |||

| Upper tertile (> 6.010) | 1.337 | 1.239-1.442 | < 0.001 |

| Intermediate tertile (4.602–6.010) | 1.170 | 1.083-1.265 | < 0.001 |

| Lower tertile (< 4.602) | 1 | ||

| Assistance model | |||

| Basic health unit | 1.104 | 1.028-1.187 | 0.007 |

| Family health unit | 1 | ||

| Maternal employment | |||

| No | 1.750 | 1.526-2.006 | < 0.001 |

| Yes | 1 | ||

| Child's age in days | 0.993 | 0.992-0.993 | < 0.001 |

CI, confidence interval.

A total of 56 units were evaluated, of which 28 were basic health units and 28 were family health units. Two initially sampled family health units were not analyzed, because one had recently been deactivated, and the other could not be visited for public safety reasons. Of these 56 analyzed and sampled units, two already had the title of “Breastfeeding-Friendly Primary Care Unit”.

The best performing unit had a score of 9.38, and the worst performance unit, of 3.00, with a median score of 5.62. The most often completed steps (Fig. 1) were step 5 (Instruct pregnant women about the importance of breastfeeding in the first hour after birth and of keeping the baby in the same room as the mother), step 4 (Listen to the concerns, experiences, and questions of pregnant women and mothers on breastfeeding practice, supporting them and strengthening their self-confidence), and step 3 (Instruct pregnant women and mothers on their rights and the benefits of breastfeeding, promoting EBF until 6 months of age and supplemented breastfeeding up to 2 years of age or older). Step 1 was the least completed (Have a written policy regarding the promotion, protection, and support of breastfeeding, to be routinely communicated to all staff of the health unit).

At the weigh-in in the pre-consultation, data were collected from 4,092 children in the first 6 months of life. A prevalence of 47.6% of EBF was found among children younger than 6 months who were followed up at the primary healthcare. This practice comprised 76.1% of children in the first month of life, 51.7% in the third month of life, and only 17.5% in the sixth month of life.

In the bivariate analysis (Table 2), children attended to at health units located in the upper tertile of performance showed a higher prevalence of EBF, followed by those assisted by units in the intermediate performance tertile. Follow-up at basic units implied a slightly higher prevalence of EBF than follow-up at family health units. The assistance provided by the maternity ward staff to breastfeed, qualified according to the maternal perception, had no significant influence on EBF. Only one quarter of mothers (24.4%) who worked outside the home were exclusively breastfeeding their children, versus half (51.6%) of those who did not work. The prevalence of EBF among infants younger than 3 months was almost twice that observed in those aged between 3 and 6 months.

In the multivariate analysis, the highest tertile of performance showed a prevalence of 34% higher EBF (PR=1.34, 95% CI: 1.24 to 1.44) and a second tertile 17% higher (PR=1.17 95% CI: 1.08 to 1.27) than the first tertile. Mothers who did not work outside the home presented a higher prevalence of EBF by 75% (PR=1.75, 95% CI: 1.53 to 2.01), and assistance at basic health units, as opposed to family health units increased the prevalence by 10% (PR=1.10, 95% CI: 1.03 to 1.19). The prevalence of EBF decreased 1% for each day of the infant's life (PR=0.993, 95% CI: 0.992 to 0.993).

DiscussionAs there is no monitoring system for the implementation stage of BFPCI, it was necessary to investigate the degree of compliance with the ten steps of this initiative in the primary healthcare network. An intermediate level of BFPCI implementation was observed in the primary health care network in the city of Rio de Janeiro, after approximately five years since the beginning of the staff training in the initiative. The highest level of implementation of steps 3, 4, and 5 demonstrates that professionals have been advising the patients on the importance of hospital routines that promote breastfeeding at birth,3 and on their rights, promoting EBF for six months and continuing it for two years or more, according to the UNICEF/WHO recommendations.10 It also demonstrates that these guidelines are being provided within a paradigm of counseling,16 where pregnant women and mothers are heard and supported, aiming at strengthening their self-confidence.

The change in this approach paradigm may ultimately be reflected in other health care activities, indicating that BFPCI can contribute to the improvement of the dialogue between the health staff and the patients, which is critical for the effectiveness of actions that have been developed. The absence of written rules (step 1), observed in most units, indicates the need for formalization of the practices that have been implemented.

When verifying to what extent the advances in the practice to ten steps of the BFPCI were associated with EBF, not only an association was found between the two, but also an increase in this association due to the increase in the degree of adherence to the BFPCI, categorized into tertiles of performance. A similar result was found by Oliveira et al.6 when comparing units with regular and poor performance regarding BFPCI, where EBF prevalence was higher in the first (38.6% vs. 23.6%, p < 0.001). The training of staff in BFPCI has been an important strategy for the implementation of this initiative. Caldeira et al.,17 in a controlled study in Minas Gerais, randomized ten units to be trained in BFPCI and ten to constitute the control group, demonstrating the impact of this strategy on the median duration of EBF. The effects of BFPCI have also been observed on children's health. Cardoso et al.18 conducted a study in a basic health unit in Rio de Janeiro comparing pre- and post-certification in BFPCI, and observed an increase in the prevalence of EBF, an increase in routine consultations with asymptomatic infants, and a reduction of consultations whose chief complaint was diarrhea or respiratory infection.

Maternal work outside the house was proven to be a risk factor for EBF weaning: it was the variable with the highest intensity of association with the outcome. This result was consistent with that found by Damião19 in Rio de Janeiro, where maternal employment decreased the likelihood of EBF in children younger than 4 months by 41%. Moreover, in a cohort study performed in Pelotas, maternal work increased the likelihood of EBF interruption at 3 months in 76%.20

In 2009, the Family Health Strategy was beginning to be structured and implemented in the city of Rio de Janeiro, covering only 3.5% of the population, the worst coverage among Brazilian capitals. In 2012, this strategy covered 35% of Rio de Janeiro's population (approximately 2.2 million people), with massive investments in training of professionals in BFPCI.8 These circumstances may be one of the factors that led the basic health units to generate a prevalence of EBF 10.4% higher than that of the family health units.

The assistance provided by the maternity ward staff to teach mothers how to nurse showed no significant association with the outcome. However, a limitation of this study was that this assistance was categorized according to maternal perception; hospital identification was not available, and therefore it was not possible to characterize them as a Baby-Friendly Hospital, a criterion used in other studies to assess the quality of hospital assistance to promote breastfeeding.21,22 In addition to this hypothesis of information bias, another source of explanation for the lack of association observed is that the mothers with more difficulty in the process of establishing breastfeeding in the maternity may have been the target of more encouragement to breastfeed, and these problems with breastfeeding may have continued after the discharge, impairing EBF.

Another limitation to be highlighted was the impossibility of controlling for other variables associated with EBF according to the literature, such as maternal characteristics: education, age, primiparity,22 child's birth weight,23 gender,24 family income,20 and living conditions,25 as in the present study these variables were not collected. However, it can be assumed that the distribution of these variables between mothers and children attending the primary care units assessed did not vary substantially, as none of the units was targeted to at-risk populations, and all of the units were from the National Unified Health System, which is mostly used by patients with low socioeconomic status.

In the present study, the children's age varied inversely with EBF, consistent with national studies,26 as well as studies in the city of Joinville27 and in the Primary Health Care network of the city of Rio de Janeiro.28 In spite of the advances made both in Brazil29 and in Rio de Janeiro,9 the six-month EBF recommended by the WHO is far from being reached.10

Therefore, a greater investment in the expansion and sustainability of BFPCI is recommended, as well as its close association with hospital strategies and other strategies to promote, protect, and support breastfeeding, so that this joint action can exert a synergistic effect on the practice of breastfeeding,30 especially its exclusive form during the first 6 months of life.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Rito RV, Oliveira MI, Brito AS. Degree of compliance with the ten steps of the Breastfeeding-Friendly Primary Care Initiative and its association with the prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2013;89:477–84.