To assess the carotid intima-media thickness and factors associated with cardiovascular disease in children and adolescents with chronic kidney disease.

Material and methodsObservational, cross-sectional study carried out at the Universidade Federal de São Paulo (chronic kidney disease outpatient clinics) with 55 patients (60% males) with a median age of 11.9 years (I25–I75: 9.2–14.8 years). Of the 55 patients, 43 were on conservative treatment and 12 were on dialysis. Serum laboratory parameters (creatinine, uric acid, C-reactive protein, total cholesterol and fractions, and triglycerides), nutritional status (z-score of body mass index, z-score of height/age), body fat (fat percentage and waist circumference), and blood pressure levels were evaluated. The carotid intima-media thickness measure was evaluated by a single ultrasonographer and compared with percentiles established according to gender and height. Data collection was performed between May 2015 and March 2016.

ResultsOf the children and adolescents with chronic kidney disease, 74.5% (95% CI: 61.0; 85.3) showed an increase (>P95) in carotid intima-media thickness. In patients with stages I and II hypertension, 90.9% had increased carotid intima-media thickness. Nutritional status, body fat and laboratory tests were not associated with increased carotid intima-media thickness. After multivariate adjustment, only puberty (PR=1.30, p=0.037) and stages I and II arterial hypertension (PR=1.42, p=0.011) were independently associated with carotid intima-media thickness alterations.

ConclusionThe prevalence of increased carotid thickness was high in children and adolescents with chronic kidney disease. Puberty and arterial hypertension were independently associated with increased carotid intima-media thickness.

Avaliar a espessura médio-intimal da carótida e os fatores associados à doença cardiovascular em crianças e adolescentes com doença renal crônica.

Material e métodosEstudo observacional transversal feito na Universidade Federal de São Paulo (ambulatórios de doença renal crônica) com 55 pacientes (60% do sexo masculino) com mediana de 11,9 anos (I25-I75: 9,2–14,8). Dos 55 pacientes, 43 estavam em tratamento conservador e 12 em terapia dialítica. Foram avaliados os parâmetros laboratoriais séricos (creatinina, ácido úrico, proteína C-reativa, colesterol total e frações e triglicérides), estado nutricional (escore z de índice de massa corpórea, escore z de estatura/idade), gordura corporal (percentual de gordura e circunferência abdominal) e pressão arterial. A medida da espessura médio-intimal da carótida foi avaliada por um único ultrassonografista e comparada com percentis estabelecidos de acordo com o sexo e a estatura. A coleta de dados foi feita entre maio de 2015 e março de 2016.

ResultadosDas crianças e adolescentes com doença renal crônica, 74,5% (IC 95%: 61,0; 85,3) apresentaram aumento (> P95) da espessura médio-intimal da carótida. Nos pacientes com hipertensão arterial estágios I e II, 90,9% apresentaram aumento da espessura médio-intimal da carótida. O estado nutricional, a gordura corporal e os exames laboratoriais não apresentaram associação com o aumento da espessura médio-intimal da carótida. Após ajuste multivariado, apenas a puberdade (RP=1,30; p=0,037) e a hipertensão arterial estágios I e II (RP=1,42; p=0,011) mostraram-se independentemente associados à alteração da espessura médio-intimal da carótida.

ConclusãoA prevalência do aumento da espessura da carótida foi elevada em crianças e adolescentes com doença renal crônica. A puberdade e a hipertensão arterial mostraram-se independentemente associadas ao aumento da espessura médio-intimal da carótida.

Cardiovascular complications are the leading cause of death in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). Risk factors attributed to cardiovascular disease (CVD) are important not only to identify potential alterations but also to evaluate the effect of treatments, aiming to reduce the risk of death.1 The presence of traditional risk factors for CVD such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, physical inactivity, smoking, and advanced age is often aggravated by several nontraditional risk factors related to poor renal function such as anemia, volume overload, altered lipid metabolism (dyslipidemia), calcium-phosphorus metabolism abnormalities (hyperparathyroidism), hyperhomocysteinemia, microalbuminuria, hyperuricemia, and chronic inflammation. All those factors increase the risk of death due to CVD in patients with CKD.2,3 Children with CKD constitute a population that is less exposed to traditional cardiovascular risk factors when compared to adult patients, thus allowing a sensitive evaluation of metabolic and hemodynamic abnormalities in the pathophysiology of arteriopathic renal disease.4

Some studies have assessed the frequency of traditional risk factors for the development of CVD in children with CKD. Silverstein et al.3 evaluated 45 transplanted children, all in stages 2–4 of CKD at the time of the study. They verified that two-thirds of the patients had at least two risk factors for CVD, while one-third of them had at least three factors.

Noninvasive vascular alteration and circulatory biomarker measurement methods are important for assessing the presence and severity of cardiovascular damage and have been commonly used to study the evolution of CVD. Measurement of carotid intima-media thickness (CIMT) has become an additional tool for early detection of arterial injury and its alteration has been associated with an increased risk of coronary events and mortality in adult patients on dialysis. In pediatrics, this alteration has been reported in both patients on dialysis and in stages 2–4 of CKD.1 Mitsnefes et al.5 observed the carotid intima-media thickness of 31 children and adolescents after kidney transplantation and found early atherosclerosis, in addition to an association between the increase in CIMT and arterial hypertension. In a study carried out by Oh et al.6 with 39 adolescents on dialysis and post-renal transplant, the carotid thickness measurement was found to be significantly higher when compared to the control group.

The increasing number of studies on the evaluation of CIMT in children and adolescents with CKD indicates this method should be introduced as a routine tool in the evaluation and monitoring of these patients. Thus, current evidence indicates that the routine assessment of cardiovascular risk is important for the early detection and treatment of vascular alterations. The present study aimed to evaluate the carotid intima-media thickness and factors associated with cardiovascular disease in children and adolescents with CKD.

MethodsThis cross-sectional, observational study included 55 patients with CKD in the dialysis and non-dialysis phases followed at the pediatric nephrology outpatient clinic of Universidade Federal de São Paulo (UNIFESP). The exclusion criteria for the study were: age <6 and ≥18 years and previous diagnosis of cardiovascular, neoplastic, infectious, or inflammatory diseases as well as systemic lupus erythematosus. Data collection was performed between May 2015 and March 2016.

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of UNIFESP and the free and informed consent form as well as the term of assent were obtained from all study participants and their parents or guardians.

Pubertal stagingPubertal staging was evaluated by the pediatricians of the service team using as criterion the development of secondary sexual characteristics as proposed by Marshall & Tanner.7

Blood pressureA digital device (Dixtal®, SP, Brazil) was used for blood pressure measurement after the patient had rested for 3–5min, with a cuff suitable for arm circumference (width and length) used at the midpoint between the olecranon and acromion. Blood pressure was confirmed by the auscultatory method and classified according to the Clinical Practice Guideline for Screening and Control of High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents.8

Nutritional status and body compositionPatients were weighed in their underwear, without shoes, on an electronic scale (Filizola®, SP, Brazil), and height was measured using a stadiometer fixed to the wall. Weight and height measures were used to calculate the z-score of body mass index (z-BMI) and z-score of height/age (z-H/A), following the reference standards and recommendations of the World Health Organization (WHO, 2007).9 Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as the weight divided by squared height (kg/m2). The abdominal circumference was measured using a flexible, inextensible tape, with an accuracy of 0.1cm and classified according to Freedman.10 The body fat percentage in boys and girls was estimated using the tricipital, bicipital, subscapular, and suprailiac skinfolds, according to the Bray's equation,11 and classified according to the percentile table proposed by McCarthy.12 A Lange® adipometer with a precision of 1mm (Beta Technology Inc., CA, USA) was used to measure the skinfolds.

% of Fat=8.71+0.19×SSF (subscapular skinfolds)+0.76×BSF (bicipital skinfolds)+0.18×SupraSF (suprailiac skinfolds)+0.33×TSF (tricipital skinfolds).

Laboratory testsThe following laboratory parameters were analyzed in the serum after a 12-hour fast in a Cobas® C 501 equipment (Roche Diagnostics®, IN, USA): creatinine, uric acid, C-reactive protein (CRP), total cholesterol (TC), HDL cholesterol (HDL-c), and triglycerides (TG). The LDL-cholesterol fraction was obtained using the equation of Friedewald et al.13 LDL-c=(TC - HDL-c+TG/5).

The I Guideline for Atherosclerosis Prevention in Childhood and Adolescence was used to identify dyslipidemias.14

Chronic kidney disease classificationChronic kidney disease was classified in five stages, according to the classification proposed by the National Kidney Foundation (NKF KDOQI).15

The glomerular filtration rate was estimated by the Schwartz equation16:

Ultrasonography of the carotid artery intima-media complexMeasurement of the media-intima complex thickness was performed by a single sonographer, blinded to the patient's identity and to the study group, using an ultrasound device with a linear transducer of 7MHz of frequency and 0.1mm resolution (General Electric®, WI, USA). The patients remained on a stretcher in the supine position, with the head turned slightly to the contralateral side, and had a 10-min rest before the examination began. The measurement was performed on the posterior wall of the left carotid artery in the longitudinal axis, including the first echogenic line and the hypoechogenic line in the distal third of the common carotid artery, as it is a more reproducible measure, due to the fact that it does not suffer interference caused by ultrasound artifacts at the site. For the classification of carotid thickness, the table of percentiles proposed by Doyon17 was used according to gender and height. Carotid intima-media thickness values >95th percentile were classified as altered.

Statistical analysisInitially, the prevalence of children and adolescents with CIMT alteration among those with CKD was estimated with the respective 95% confidence interval (95% CI). Qualitative variables were described as number and percentage (%), whereas the quantitative variables were described as median and interquartile range (I25; I75). Aiming to estimate the association of CIMT alterations with risk factors, the prevalence ratio (PR) and its 95% CI were calculated, with CIMT alteration as the dependent variable and the several exposure factors as the independent variables. The variables selected in the univariate analysis that showed a p-value <0.20 were selected to constitute the multivariate model. We chose to calculate the prevalence ratio instead of calculating the odds ratio, since the evaluated event (CIMT alteration) was frequent, i.e. with prevalence ≥20%. The prevalence ratios and their respective 95% confidence intervals were estimated using the generalized linear model (GLM) with binomial distribution and log link function. All tests were two-sided, and a p-value <5% (p<0.05) was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using the STATA software, version 14.2 for Windows (STATA, College Station, TX, USA).

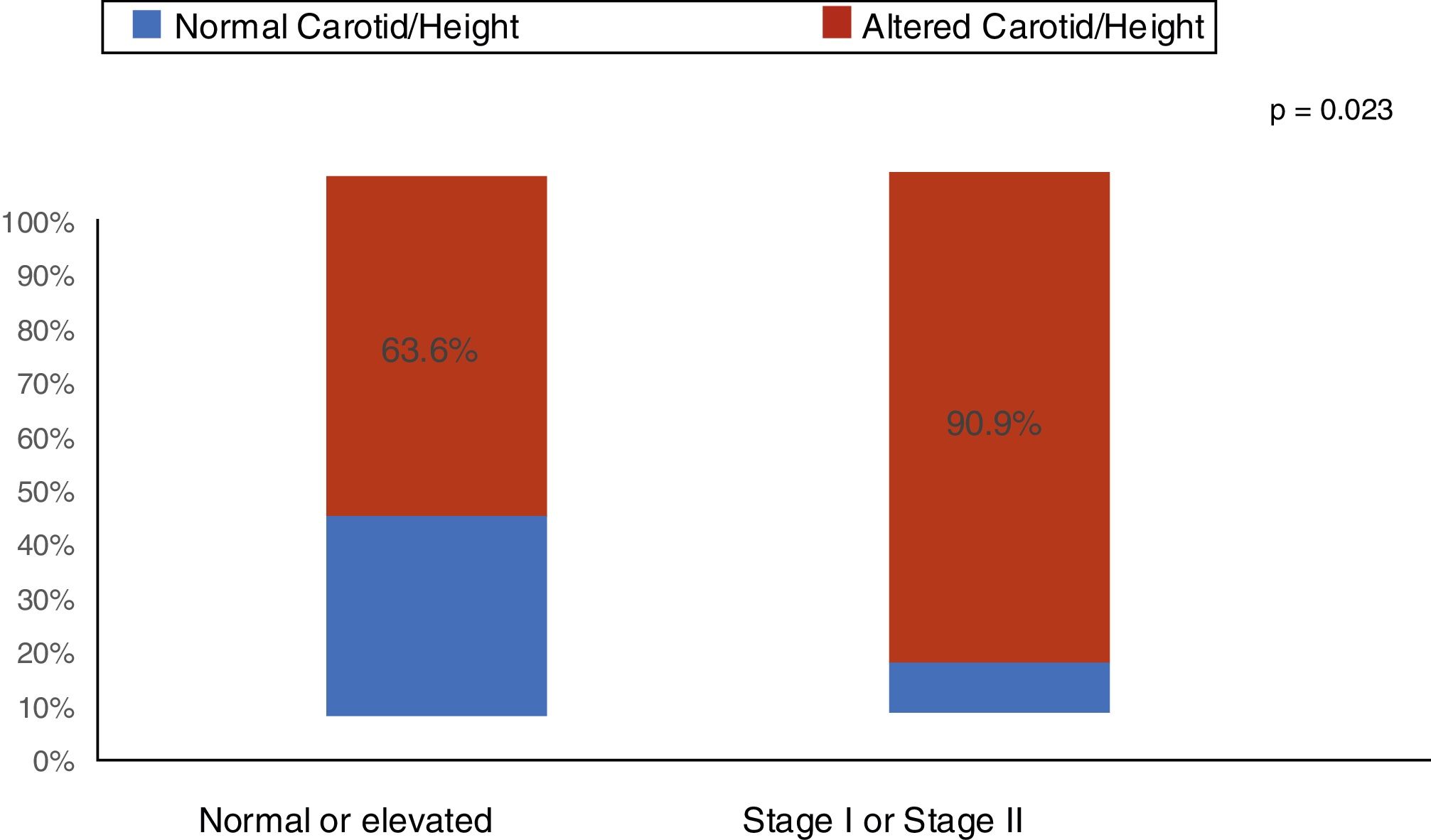

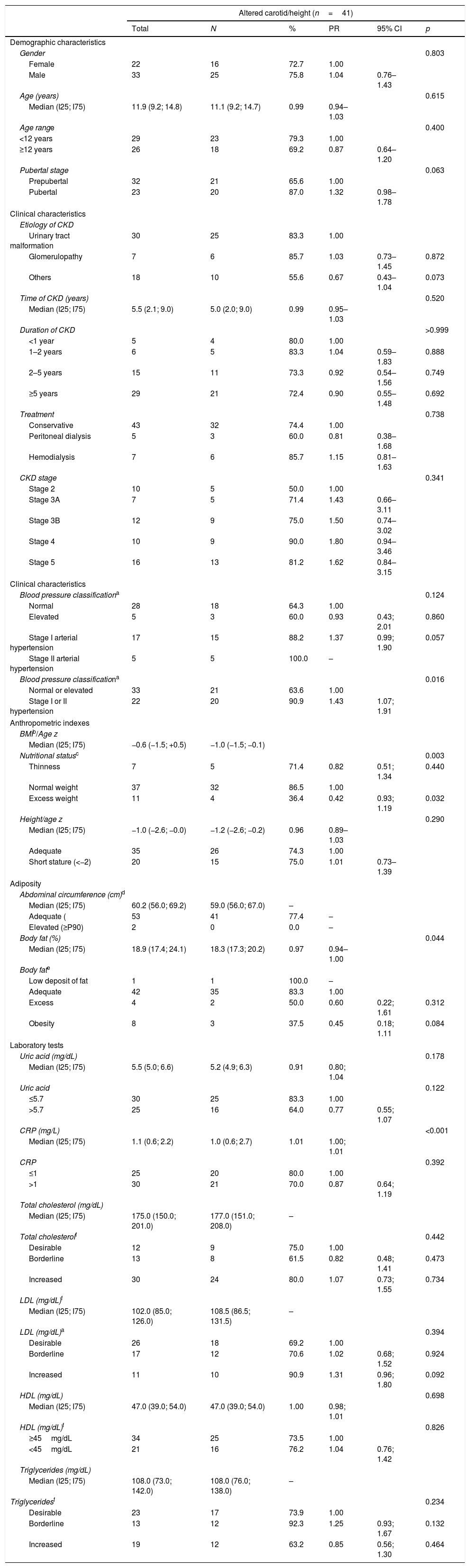

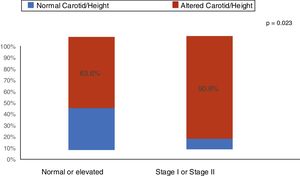

ResultsThe median age was 11.9 years (I25–I75: 9.2–14.8 years). Of the 55 patients (60% males), 43 received conservative treatment and 12 were on dialysis therapy. An increase (above the 95th percentile) in CIMT was found in 74.5% (95% CI: 61.0; 85.3) of the children and adolescents with CKD. The main clinical and demographic characteristics are shown in Table 1. As shown in Fig. 1, among the patients with stage I and II arterial hypertension, 90.9% had increased CIMT. Nutritional status and body fat were not associated with increased CIMT (Table 1). Regarding laboratory tests, C-reactive protein and uric acid were elevated in 54.5% and 45.5% of patients with CKD, respectively. There was no association of increased C-reactive protein and uric acid with increased CIMT (Table 1).

Demographic, clinical, anthropometric, and laboratory characteristics of pediatric patients with chronic kidney disease, according to the presence of carotid intimal-media thickness alteration.

| Altered carotid/height (n=41) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | N | % | PR | 95% CI | p | |

| Demographic characteristics | ||||||

| Gender | 0.803 | |||||

| Female | 22 | 16 | 72.7 | 1.00 | ||

| Male | 33 | 25 | 75.8 | 1.04 | 0.76–1.43 | |

| Age (years) | 0.615 | |||||

| Median (I25; I75) | 11.9 (9.2; 14.8) | 11.1 (9.2; 14.7) | 0.99 | 0.94–1.03 | ||

| Age range | 0.400 | |||||

| <12 years | 29 | 23 | 79.3 | 1.00 | ||

| ≥12 years | 26 | 18 | 69.2 | 0.87 | 0.64–1.20 | |

| Pubertal stage | 0.063 | |||||

| Prepubertal | 32 | 21 | 65.6 | 1.00 | ||

| Pubertal | 23 | 20 | 87.0 | 1.32 | 0.98–1.78 | |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||||

| Etiology of CKD | ||||||

| Urinary tract malformation | 30 | 25 | 83.3 | 1.00 | ||

| Glomerulopathy | 7 | 6 | 85.7 | 1.03 | 0.73–1.45 | 0.872 |

| Others | 18 | 10 | 55.6 | 0.67 | 0.43–1.04 | 0.073 |

| Time of CKD (years) | 0.520 | |||||

| Median (I25; I75) | 5.5 (2.1; 9.0) | 5.0 (2.0; 9.0) | 0.99 | 0.95–1.03 | ||

| Duration of CKD | >0.999 | |||||

| <1 year | 5 | 4 | 80.0 | 1.00 | ||

| 1–2 years | 6 | 5 | 83.3 | 1.04 | 0.59–1.83 | 0.888 |

| 2–5 years | 15 | 11 | 73.3 | 0.92 | 0.54–1.56 | 0.749 |

| ≥5 years | 29 | 21 | 72.4 | 0.90 | 0.55–1.48 | 0.692 |

| Treatment | 0.738 | |||||

| Conservative | 43 | 32 | 74.4 | 1.00 | ||

| Peritoneal dialysis | 5 | 3 | 60.0 | 0.81 | 0.38–1.68 | |

| Hemodialysis | 7 | 6 | 85.7 | 1.15 | 0.81–1.63 | |

| CKD stage | 0.341 | |||||

| Stage 2 | 10 | 5 | 50.0 | 1.00 | ||

| Stage 3A | 7 | 5 | 71.4 | 1.43 | 0.66–3.11 | |

| Stage 3B | 12 | 9 | 75.0 | 1.50 | 0.74–3.02 | |

| Stage 4 | 10 | 9 | 90.0 | 1.80 | 0.94–3.46 | |

| Stage 5 | 16 | 13 | 81.2 | 1.62 | 0.84–3.15 | |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||||

| Blood pressure classificationa | 0.124 | |||||

| Normal | 28 | 18 | 64.3 | 1.00 | ||

| Elevated | 5 | 3 | 60.0 | 0.93 | 0.43; 2.01 | 0.860 |

| Stage I arterial hypertension | 17 | 15 | 88.2 | 1.37 | 0.99; 1.90 | 0.057 |

| Stage II arterial hypertension | 5 | 5 | 100.0 | – | ||

| Blood pressure classificationa | 0.016 | |||||

| Normal or elevated | 33 | 21 | 63.6 | 1.00 | ||

| Stage I or II hypertension | 22 | 20 | 90.9 | 1.43 | 1.07; 1.91 | |

| Anthropometric indexes | ||||||

| BMIb/Age z | ||||||

| Median (I25; I75) | −0.6 (−1.5; +0.5) | −1.0 (−1.5; −0.1) | ||||

| Nutritional statusc | 0.003 | |||||

| Thinness | 7 | 5 | 71.4 | 0.82 | 0.51; 1.34 | 0.440 |

| Normal weight | 37 | 32 | 86.5 | 1.00 | ||

| Excess weight | 11 | 4 | 36.4 | 0.42 | 0.93; 1.19 | 0.032 |

| Height/age z | 0.290 | |||||

| Median (I25; I75) | −1.0 (−2.6; −0.0) | −1.2 (−2.6; −0.2) | 0.96 | 0.89–1.03 | ||

| Adequate | 35 | 26 | 74.3 | 1.00 | ||

| Short stature (<−2) | 20 | 15 | 75.0 | 1.01 | 0.73–1.39 | |

| Adiposity | ||||||

| Abdominal circumference (cm)d | ||||||

| Median (I25; I75) | 60.2 (56.0; 69.2) | 59.0 (56.0; 67.0) | – | |||

| Adequate ( | 53 | 41 | 77.4 | – | ||

| Elevated (≥P90) | 2 | 0 | 0.0 | – | ||

| Body fat (%) | 0.044 | |||||

| Median (I25; I75) | 18.9 (17.4; 24.1) | 18.3 (17.3; 20.2) | 0.97 | 0.94–1.00 | ||

| Body fate | ||||||

| Low deposit of fat | 1 | 1 | 100.0 | – | ||

| Adequate | 42 | 35 | 83.3 | 1.00 | ||

| Excess | 4 | 2 | 50.0 | 0.60 | 0.22; 1.61 | 0.312 |

| Obesity | 8 | 3 | 37.5 | 0.45 | 0.18; 1.11 | 0.084 |

| Laboratory tests | ||||||

| Uric acid (mg/dL) | 0.178 | |||||

| Median (I25; I75) | 5.5 (5.0; 6.6) | 5.2 (4.9; 6.3) | 0.91 | 0.80; 1.04 | ||

| Uric acid | 0.122 | |||||

| ≤5.7 | 30 | 25 | 83.3 | 1.00 | ||

| >5.7 | 25 | 16 | 64.0 | 0.77 | 0.55; 1.07 | |

| CRP (mg/L) | <0.001 | |||||

| Median (I25; I75) | 1.1 (0.6; 2.2) | 1.0 (0.6; 2.7) | 1.01 | 1.00; 1.01 | ||

| CRP | 0.392 | |||||

| ≤1 | 25 | 20 | 80.0 | 1.00 | ||

| >1 | 30 | 21 | 70.0 | 0.87 | 0.64; 1.19 | |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | ||||||

| Median (I25; I75) | 175.0 (150.0; 201.0) | 177.0 (151.0; 208.0) | – | |||

| Total cholesterolf | 0.442 | |||||

| Desirable | 12 | 9 | 75.0 | 1.00 | ||

| Borderline | 13 | 8 | 61.5 | 0.82 | 0.48; 1.41 | 0.473 |

| Increased | 30 | 24 | 80.0 | 1.07 | 0.73; 1.55 | 0.734 |

| LDL (mg/dL)f | ||||||

| Median (I25; I75) | 102.0 (85.0; 126.0) | 108.5 (86.5; 131.5) | – | |||

| LDL (mg/dL)a | 0.394 | |||||

| Desirable | 26 | 18 | 69.2 | 1.00 | ||

| Borderline | 17 | 12 | 70.6 | 1.02 | 0.68; 1.52 | 0.924 |

| Increased | 11 | 10 | 90.9 | 1.31 | 0.96; 1.80 | 0.092 |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 0.698 | |||||

| Median (I25; I75) | 47.0 (39.0; 54.0) | 47.0 (39.0; 54.0) | 1.00 | 0.98; 1.01 | ||

| HDL (mg/dL)f | 0.826 | |||||

| ≥45mg/dL | 34 | 25 | 73.5 | 1.00 | ||

| <45mg/dL | 21 | 16 | 76.2 | 1.04 | 0.76; 1.42 | |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | ||||||

| Median (I25; I75) | 108.0 (73.0; 142.0) | 108.0 (76.0; 138.0) | – | |||

| Triglyceridesf | 0.234 | |||||

| Desirable | 23 | 17 | 73.9 | 1.00 | ||

| Borderline | 13 | 12 | 92.3 | 1.25 | 0.93; 1.67 | 0.132 |

| Increased | 19 | 12 | 63.2 | 0.85 | 0.56; 1.30 | 0.464 |

Interquartile (I25–I75); PR, prevalence ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

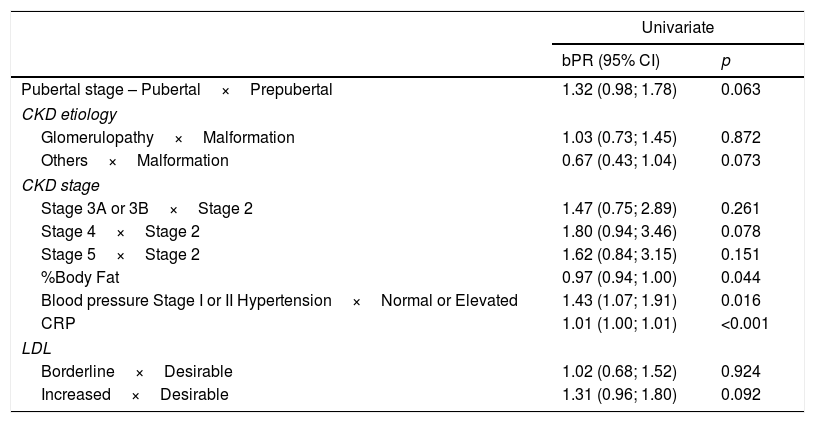

Table 2 shows the variables chosen to constitute the multivariate model, that is, the ones that showed results with a p-value <0.2.

Univariate analysis of factors associated with increased carotid intima-media thickness in pediatric patients with chronic kidney disease.

| Univariate | ||

|---|---|---|

| bPR (95% CI) | p | |

| Pubertal stage – Pubertal×Prepubertal | 1.32 (0.98; 1.78) | 0.063 |

| CKD etiology | ||

| Glomerulopathy×Malformation | 1.03 (0.73; 1.45) | 0.872 |

| Others×Malformation | 0.67 (0.43; 1.04) | 0.073 |

| CKD stage | ||

| Stage 3A or 3B×Stage 2 | 1.47 (0.75; 2.89) | 0.261 |

| Stage 4×Stage 2 | 1.80 (0.94; 3.46) | 0.078 |

| Stage 5×Stage 2 | 1.62 (0.84; 3.15) | 0.151 |

| %Body Fat | 0.97 (0.94; 1.00) | 0.044 |

| Blood pressure Stage I or II Hypertension×Normal or Elevated | 1.43 (1.07; 1.91) | 0.016 |

| CRP | 1.01 (1.00; 1.01) | <0.001 |

| LDL | ||

| Borderline×Desirable | 1.02 (0.68; 1.52) | 0.924 |

| Increased×Desirable | 1.31 (0.96; 1.80) | 0.092 |

bPR, crude prevalence ratio (univariate model).

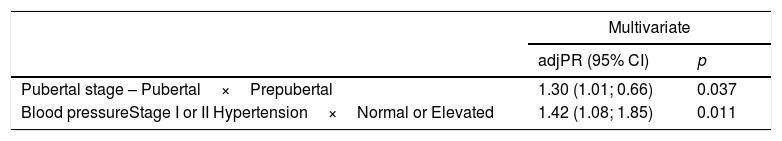

After the multivariate adjustment, as shown in Table 3, only puberty (PR=1.30, 95% CI: 1.01; 0.66; p=0.037) and arterial hypertension stages I and II (PR=1.42, 95% CI: 1.08; 1.85; p=0.011) were independently associated with CIMT alteration.

Multivariate analysis of factors associated with increased mean carotid intima-media thickness in pediatric patients with chronic kidney disease.

| Multivariate | ||

|---|---|---|

| adjPR (95% CI) | p | |

| Pubertal stage – Pubertal×Prepubertal | 1.30 (1.01; 0.66) | 0.037 |

| Blood pressureStage I or II Hypertension×Normal or Elevated | 1.42 (1.08; 1.85) | 0.011 |

adjPR, adjusted prevalence ratio (multivariate model).

The present study with children and adolescents in stages 2–5 of CKD showed that the presence of certain risk factors for cardiovascular disease such as arterial hypertension (40%), increase in LDL cholesterol (51.9%), pubertal stage (58.2%), and inflammation (54.5%) is frequently observed. Increased thickness of the media-intima layer was evidenced in 90.9% of patients with arterial hypertension. It should be noted that arterial hypertension and puberty were the variables independently associated with increased carotid thickness in pediatric patients with CKD.

Nutritional status and body compositionThe importance of anthropometric markers is evidenced by their association with mortality and widely described in pediatric patients with CKD.

BMI is generally used as an indicator of adiposity in children and adolescents. The increase in BMI in childhood is a strong predictor of premature death due to CVD in middle and late adulthood. However, obesity-related comorbidities are more associated with the pattern of body fat distribution than with total fat mass.18 Abdominal circumference is a more sensitive indicator than BMI for CVD risk assessment and is associated with atherogenicity in children and adolescents without CKD.19 Although there is a higher risk of CVD in these patients, the results of this study showed no association between abdominal adiposity and body fat percentage with carotid alteration in the multivariate analysis.

In our study, 67.3% of the patients had adequate height for age. Contrary to our findings, Ku et al.20 showed that children and adolescents on dialysis or after renal transplant with short stature had an increased risk of mortality, mainly due to cardiac and infectious causes.

A study carried out in the United States by Wong et al.21 showed that the mortality risk increased by 14% for each unit reduction in height z-scores, regardless of the type of treatment (dialysis or transplant).

The excess fat variables (anthropometric index – BMI, and body composition – fat mass and central adiposity) and short stature were not part of the multivariate analysis. In this study, patients received dietary intervention with a nutritionist, which reflects on nutrition education and monitoring, resulting in better quality of eating among the assessed population. A recent study observed changes in nutritional status and body composition in adult patients with CKD followed for 6 months after nutritional guidance.22

Laboratory testsLipid alterations have been established as a risk factor for the development of atherosclerosis. The association between dyslipidemia and increased carotid intima-media thickness has been evidenced in studies with children. Brady et al. evaluated pediatric patients in stages 2–4 of CKD and demonstrated this association.23 In the study by Khandelwal et al.,24 the association of increased carotid media-intima thickness, triglycerides, total cholesterol, and LDL cholesterol was found in children at different stages of CKD.

In this study, LDL cholesterol showed an association with altered carotid thickness in the univariate analysis, but the multivariate analysis did not confirm this association.

Inflammation is one of the events responsible for CVD in CKD, and high levels of inflammatory markers are identified in children undergoing dialysis.25 Our findings demonstrated that although high levels of CRP showed an association with altered carotid thickness in the univariate analysis, no association was observed in the multivariate analysis.

Hyperuricemia has been widely studied in patients with CKD, as it is a modifiable cardiovascular risk factor and plays a significant role in endothelial dysfunction, inflammation and atherosclerosis.18 In our study, 45.5% of the patients had hyperuricemia, and this marker was not associated with altered carotid thickness.

Arterial hypertension and pubertySystemic arterial hypertension (SAH) is one of the most critical determinants of renal disease progression in children and a major risk factor for cardiovascular complications. The literature findings show a correlation between high blood pressure and signs of arterio/atherosclerosis in children, being one of the most important modifiable factors among the risk factors for CVD.26

Our study showed that of the 40% of stages I and II hypertensive patients 90.4% had an increase in carotid thickness, whereas in the group with normal or elevated blood pressure more than 50% (63.6%) of patients already had an increase in the carotid intima-media thickness. When comparing the two groups, a statistically significant difference was observed in the proportions of the media-intima layer alteration (p=0.023). Arterial hypertension is a frequent finding in patients with CKD and several studies have demonstrated this risk factor for cardiovascular complications. In the study by Flynn et al.27 including 586 children with CKD, it was observed that arterial hypertension was present in 54% of the patients. Despite the use of antihypertensive medication, 48% of these children showed inadequate blood pressure control. Another North American study with pediatric transplant patients showed that 48% of uncontrolled arterial hypertension at CKD onset increased to 50–75% in the final stage of CKD. After transplantation, the reported prevalence of hypertension was 50–87%.28

Carotid artery alterations were also confirmed by Brady et al.,23 who assessed risk factors for CVD and found that arterial hypertension was significantly associated with increased carotid thickness in children aged 2–18 years with CKD. Poyrazoglu et al.29 assessed the carotid media-intima thickness of 34 children with CKD and found an increase in CIMT in this population, as well as an association between increased CIMT and arterial hypertension.

As for pubertal staging, pubertal patients (G2/M2–G5/M5) showed a greater association with increased carotid thickness (PR=1.30; 95% CI: 1.01; 0.66; p=0.037). In a study with healthy children carried out by Baroncini et al.30 it was observed that carotid thickness alterations were associated with increased age, as seen in adults. These findings could be related to the fact that at puberty, hormonal changes may induce an increase in the percentage of total body fat and alterations in lipoproteins, especially LDL-c increase.30 Another possible explanation would be that CIMT increases in response to the physiological vessel reaction in order to adapt to the blood pressure increase that occurs with advancing age.17 Moreover, in a study with 24 children with CKD carried out by Bilginer et al.,28 an association was found between the time of CKD and the increase in CIMT.

Among the limitations of this study, a larger sample size could provide greater power and lower confidence intervals. Another limitation is the fact that, if the study had a control group, the occurrence of CVD risk factors non-specific to CKD could be compared in the group of studied patients.

We conclude that puberty and arterial hypertension are important determinants in CIMT increase. Moreover, the assessed risk factors play an important role in CVD-associated morbidity and mortality in children with CKD. The implications of these findings require investigation in further studies. However, early and routine assessment of these factors, together with appropriate intervention, is crucial to prevent CVD progression and mortality in these patients.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Lopes R, Morais MB, Oliveira FL, Brecheret AP, Abreu AL, Andrade MC. Evaluation of carotid intima-media thickness and factors associated with cardiovascular disease in children and adolescents with chronic kidney disease. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2019;95:696–704.