To assess the annual burden of early neonatal deaths associated with perinatal asphyxia in infants weighing ≥2500g in Brazil from 2005 to 2010.

MethodsThe population study enrolled all live births of infants with birth weight ≥2500g and without malformations who died up to six days after birth with perinatal asphyxia, defined as intrauterine hypoxia, asphyxia at birth, or meconium aspiration syndrome. The cause of death was written in any field of the death certificate, according to International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (P20.0, P21.0, and P24.0). An active search was performed in 27 Brazilian federative units. The chi-squared test for trend was applied to analyze early neonatal mortality ratios associated with perinatal asphyxia by study year.

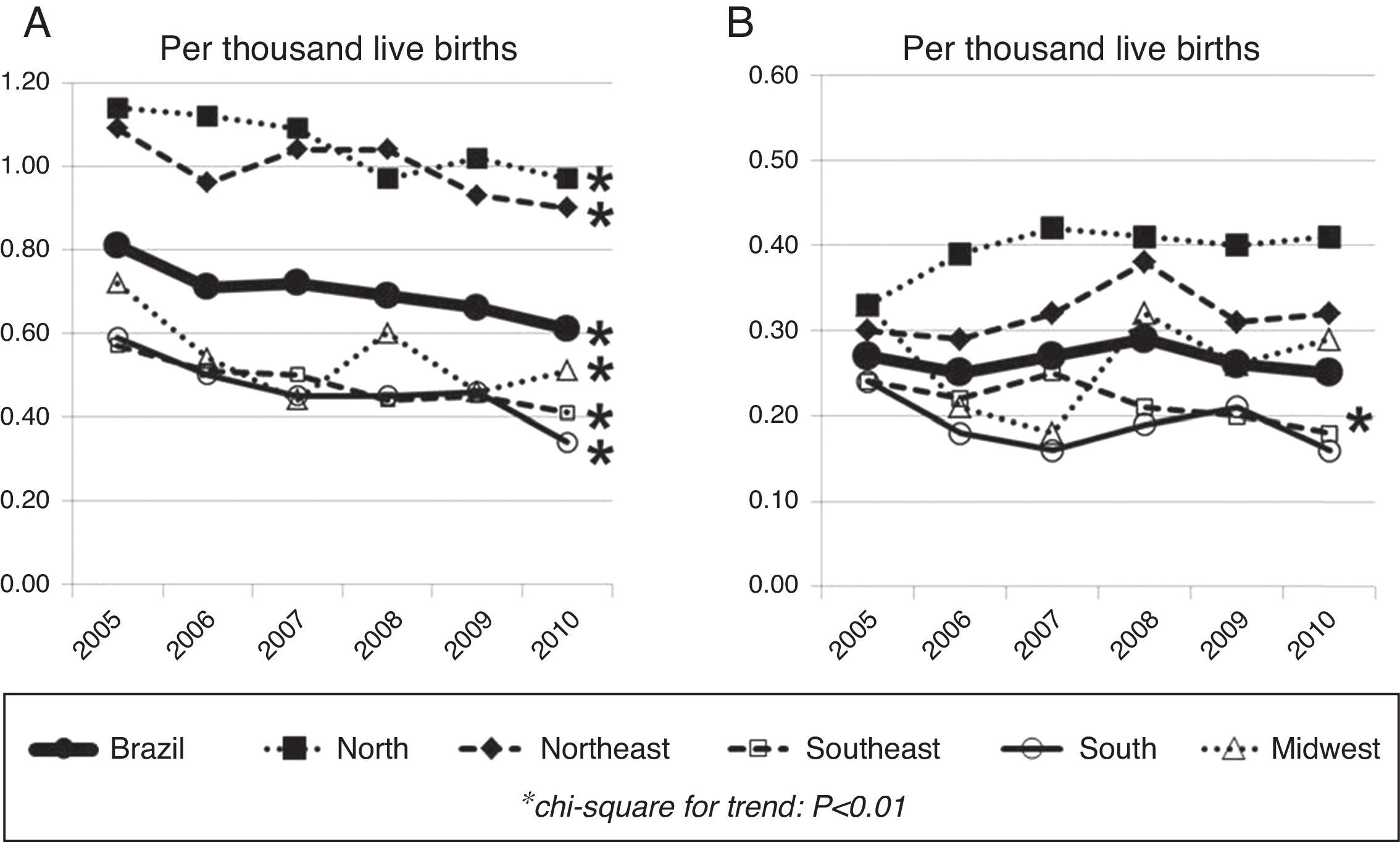

ResultsA total of 10,675 infants weighing ≥2500g without malformations died within six days after birth with perinatal asphyxia. Deaths occurred in the first 24h after birth in 71% of the infants. Meconium aspiration syndrome was reported in 4076 (38%) of these deaths. The asphyxia-specific early neonatal mortality ratio decreased from 0.81 in 2005 to 0.65 per 1000 live births in 2010 in Brazil (p<0.001); the meconium aspiration syndrome-specific early neonatal mortality ratio remained between 0.20 and 0.29 per 1000 live births during the study period.

ConclusionsDespite the decreasing rates in Brazil from 2005 to 2010, early neonatal mortality rates associated with perinatal asphyxia in infants in the better spectrum of birth weight and without congenital malformations are still high, and meconium aspiration syndrome plays a major role.

Avaliar a taxa anual de óbitos neonatais precoces associados à asfixia perinatal em neonatos de peso ≥2.500g no Brasil de 2005 a 2010.

MétodosA população do estudo envolveu todos os nascidos vivos de neonatos com peso ao nascer ≥2.500g e sem malformações que morreram até seis dias após o nascimento por asfixia perinatal, definida como hipóxia intrauterina, asfixia no nascimento ou síndrome de aspiração de mecônio. A causa do óbito foi escrita em qualquer linha do atestado de óbito, de acordo com a Classificação Internacional de Doenças, 10a Revisão (P20.0, P21.0 e P24.0). Foi feita uma pesquisa ativa em 27 unidades federativas brasileiras. O teste Qui-quadrado de tendência foi aplicado para analisar os índices de mortalidade neonatal associados a asfixia perinatal até o ano do estudo.

ResultadosUm total de 10.675 neonatos com peso ≥2.500g sem malformações morreu até 0-6 dias após o nascimento por asfixia perinatal. Os óbitos ocorreram nas primeiras 24 horas após o nascimento em 71% dos neonatos. A síndrome de aspiração de mecônio foi relatada em 4.076 (38%) dos óbitos. O índice de mortalidade neonatal precoce relacionada à asfixia caiu de 0,81 em 2005 para 0,65 por 1.000 nascidos vivos em 2010 no Brasil (p<0,001); o índice de mortalidade neonatal precoce relacionada a síndrome de aspiração de mecônio permaneceu entre 0,20-0,29 por 1.000 nascidos vivos durante o período do estudo.

ConclusõesApesar da redução nas taxas no Brasil de 2005 a 2010, as taxas de mortalidade neonatal precoce associadas à asfixia perinatal em neonatos no melhor espectro de peso ao nascer e sem malformações congênitas ainda são altas, e a síndrome de aspiração de mecônio desempenha um importante papel.

Recently, the deaths of children younger than 5 years of age have decreased dramatically, with 3.6 million fewer deaths in 2013 when compared with 2000.1 This reduction is primarily attributed to progress in prevention and treatment of infectious diseases in post-neonatal infants and children aged 1–4 years.2 With this decrease in infections, neonatal conditions have gained prominence. In 1990, neonatal deaths accounted for 37.4% of deaths in children younger than 5 years of age, compared with 41.6% in 2013.3 The three leading causes of the 2.9 million annual neonatal deaths worldwide are preterm birth complications (1.0 million), intrapartum conditions (0.7 million), and infections (0.6 million). Intrapartum-related conditions and preterm birth dominate in the early neonatal period.4

In 2013, the Maternal and Child Epidemiology Estimation Group reported that intrapartum-related events accounted for 24% of neonatal deaths in the world.1 Two-thirds of these deaths occured in South Asia and Africa.5 High-income countries have a low incidence of asphyxia-related deaths, at approximately 12%.6 Conversely, around 740,000–1,480,000 yearly neonatal deaths worldwide occur among infants with birth weight ≥2500g; in low- and middle-income countries, most of these deaths are associated with intrapartum asphyxia.7

Brazil, the largest South American country, with a population of approximately 200 million and 3 million births per year, has experienced economic and social progress from 2003 to 2013, in which more than 26 million people emerged from poverty and inequality was reduced.8 The fourth Millennium Development Goal was achieved by the country with a 78% reduction of under-five mortality rate from 1990 (61.5 per 1000 live births) to 2013 (13.7 per 1000 live births).9 Estimates and uncertainty intervals for early and late neonatal deaths per 1000 live births in Brazil in 2013 were 7.5 (6.6–8.4) and 2.6 (2.4–2.7), respectively.3 The data compiled by the State Health Departments and reported to the Brazilian Ministry of Health indicated that intrauterine hypoxia and birth asphyxia represented 7% of the basic causes of deaths between 0 and 6 days after birth in 2014.10

Term infants have the lowest risk of neonatal and infant mortality. In 11 countries of Western Europe, the infant mortality rates for those born ≥37 weeks gestation were below 2.0 per 1000 live births in 2010.11 The neonatal mortality rate for infants with a birth weight ≥2500g in 2010 was 0.73 per 1000 live births in the United States12 and 2.63 in Brazil.10 The burden of intrapartum-related conditions associated with this high neonatal mortality rate in non-low birth weight infants in Brazil has not been well evaluated.

The present study assessed the yearly burden and the primary epidemiological characteristics of early deaths associated with perinatal asphyxia of infants with birth weight ≥2500g without congenital malformations in Brazil from 2005 to 2010, considering the presence of intrauterine hypoxia, birth asphyxia, or meconium aspiration syndrome in any field of the death certificates.

MethodsThis was a population-based study of all live births weighing ≥2500g without congenital malformations, who died with birth asphyxia up to 168h after birth from January 1, 2005 to December 31, 2010 in Brazil. The project was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Universidade Federal de São Paulo, which was the leading center for this project.

In each of the 27 states of Brazil, two investigators made an active search of all neonates who had died within the first week after birth. Both investigators were the local coordinators of the Neonatal Resuscitation Program of the Brazilian Pediatric Society. The original death certificates and/or the electronic files were obtained at the State Health Departments of 26 states and from the State Data Analysis System Foundation (Fundação Sistema Estadual de Análise de Dados) for the state of São Paulo.

The deaths associated with the presence of perinatal asphyxia included in the study were reported in any field of the death certificate as any of the following causes, according to the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD 10): P20.0 − intrauterine hypoxia first noted before the onset of labor; P20.1 − intrauterine hypoxia first noted during labor and delivery; P20.9 − intrauterine hypoxia, unspecified; P21.0 − severe birth asphyxia; P21.1 – mild and moderate birth asphyxia; P21.9 − birth asphyxia, unspecified; or P24.0 − neonatal aspiration of meconium.13 This study did not include deaths caused by neonatal aspiration of secretions other than meconium, deaths described as neonatal cerebral depression, or fetal deaths. All newborns with a congenital malformation reported in any field of the death certificate were excluded.

Two independent professionals entered the data for each death into an electronic file that was specifically created for the study. The recorded variables extracted from the death certificates were: date and time of birth and death; city and state where the mother lived and where the baby died; place where the neonate died (hospital, other health facility, home, street); maternal age, years of schooling (none, 1–3, 4–7, 8–11, ≥12) and place of work (home, outside home); number of previous births; weeks of gestation (<22, 22–27, 28–31, 32–36, 37–41, ≥42); single or multiple gestation; cesarean section or vaginal delivery; birth weight (g); neonatal sex and race (white, black, Asian, Native Brazilian; mulatto); and ICD-10 code at fields Ia, Ib, Ic, Id, and II.

In order to calculate the perinatal asphyxia-specific mortality ratio and the meconium aspiration syndrome-specific mortality ratio, the number of live births from 2005 to 2010 with weight ≥2500g without malformations reported in the birth certificates was obtained at the national open-access public health system database maintained by the Brazilian Ministry of Health.10 Such ratios were analyzed yearly for the country as a whole and for each of the five regions of Brazil.

Maternal and neonatal characteristics were compared across the years of the study. All of the comparisons used a descriptive statistical analysis, chi-squared test, and SPSS software (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 21.0, USA) to determine trends.

ResultsThis study found 27,800 early neonatal deaths associated with perinatal asphyxia between 2005 and 2010 in Brazil. Among them, 2767 (10%) had a diagnosis of congenital malformation on the death certificate and 823 (3%) were non-viable infants with either a gestational age <22 weeks or a birth weight <400g. Among the 24,210 potentially viable infants without congenital malformations, 2861 (12%) did not have birth weight data. Patients with and without birth weight data were similar regarding maternal age, occupation and parity, multiple gestation, gestational age, and neonatal gender. Among the 21,349 deaths with birth weight information, the study found 10,675 (50%) infants with birth weight ≥2500g and without malformations who died with perinatal asphyxia related conditions.

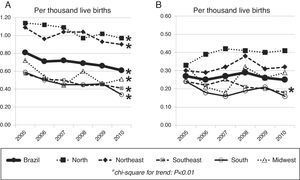

In Brazil, the rate of early neonatal deaths associated with perinatal asphyxia per 1000 live births of infants with birth weight ≥2500g without congenital malformations decreased from 0.81 in 2005 to 0.65 in 2010 (p<0.001). This reduction was significant in all Brazilian regions of the country (Fig. 1A). The ratio of early neonatal deaths associated with meconium aspiration syndrome per 1000 live births of infants weighing ≥2500g without malformations remained between 0.20 and 0.29 during the study period in Brazil, with a reduction only in the southeast region of the country: from 0.24 per 1000 live births in 2005 to 0.18 in 2010 (p=0.005; Fig. 1B).

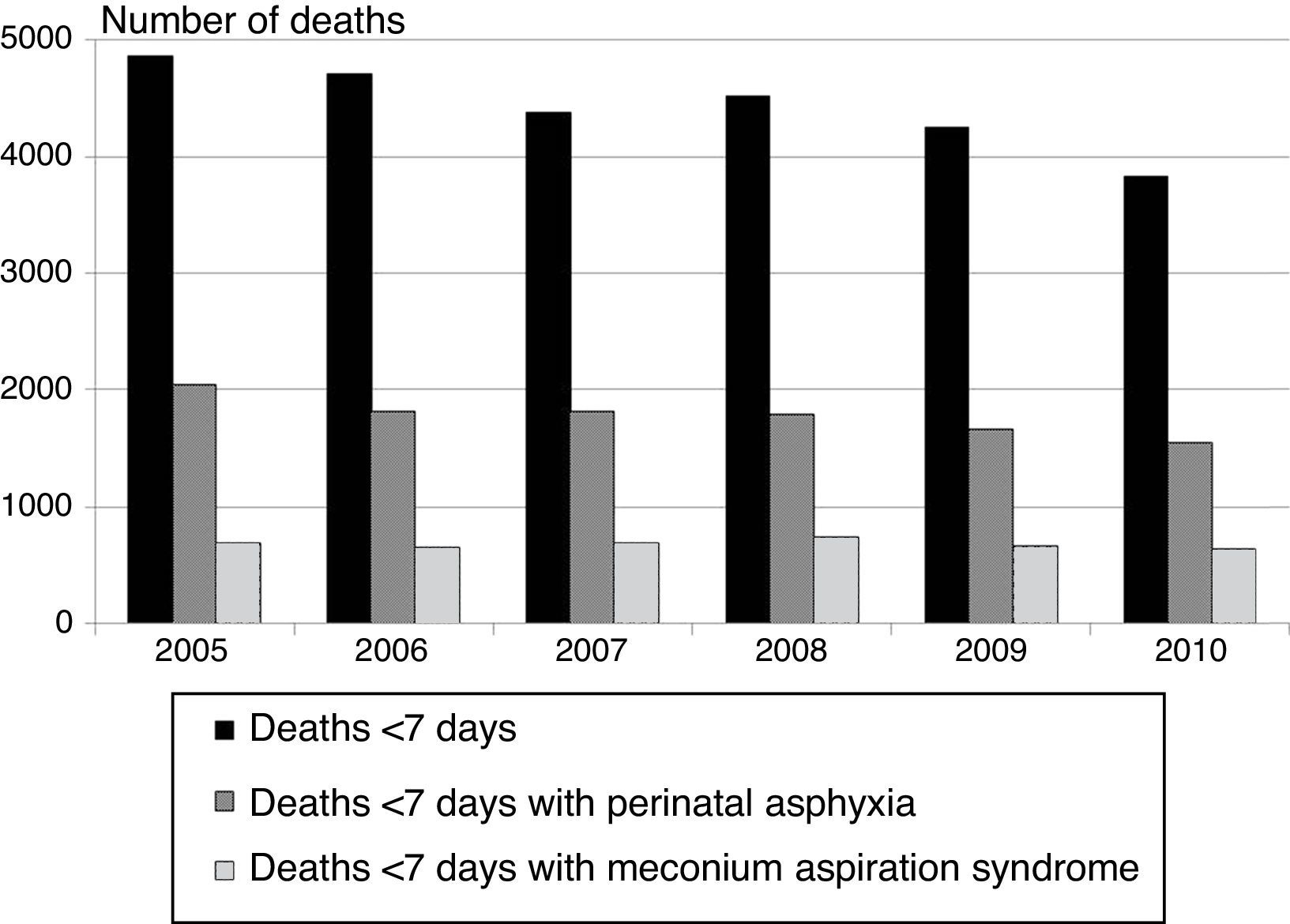

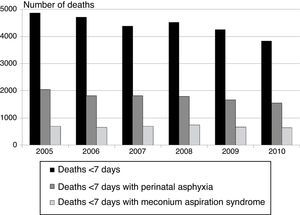

The absolute number of early neonatal deaths in Brazil, extracted from the database maintained by the Brazilian Ministry of Health,10 and the number of deaths associated with asphyxia and meconium aspiration syndrome are shown in Fig. 2. Early neonatal deaths associated with perinatal asphyxia accounted for 40% of all early neonatal deaths of infants weighing ≥2500g without malformations during the study period in the country. Early neonatal deaths associated with meconium aspiration syndrome increased from 14.4% of all early neonatal deaths of infants weighing ≥2500g without malformations in Brazil in 2005 to 16.6% in 2010 (p<0.001). Among the 4076 deaths with meconium aspiration syndrome, 1976 (48%) had also diagnosis of intrauterine hypoxia or birth asphyxia in at least one of the fields of the death certificate.

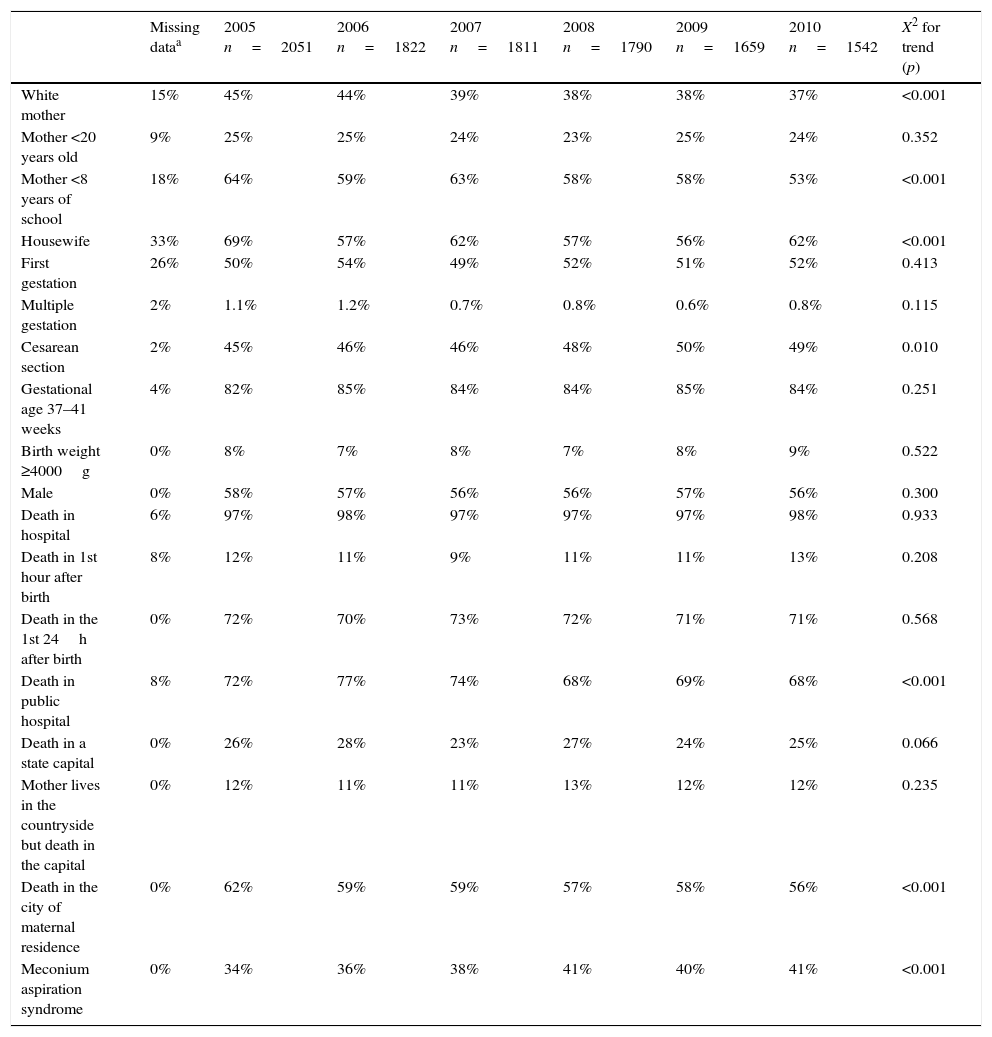

The characteristics of the 10,675 infants weighing ≥2500g without malformations who had an early neonatal death associated with perinatal asphyxia are shown in Table 1. The contribution of the North and Northeast Brazilian regions to early neonatal deaths associated with perinatal asphyxia increased from 58% in 2005 to 60% in 2010 (p=0.040).

Characteristics of the 10,675 early neonatal deaths associated with perinatal asphyxia in infants with birth weight ≥2500g without malformations, according to year of death.

| Missing dataa | 2005 n=2051 | 2006 n=1822 | 2007 n=1811 | 2008 n=1790 | 2009 n=1659 | 2010 n=1542 | X2 for trend (p) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White mother | 15% | 45% | 44% | 39% | 38% | 38% | 37% | <0.001 |

| Mother <20 years old | 9% | 25% | 25% | 24% | 23% | 25% | 24% | 0.352 |

| Mother <8 years of school | 18% | 64% | 59% | 63% | 58% | 58% | 53% | <0.001 |

| Housewife | 33% | 69% | 57% | 62% | 57% | 56% | 62% | <0.001 |

| First gestation | 26% | 50% | 54% | 49% | 52% | 51% | 52% | 0.413 |

| Multiple gestation | 2% | 1.1% | 1.2% | 0.7% | 0.8% | 0.6% | 0.8% | 0.115 |

| Cesarean section | 2% | 45% | 46% | 46% | 48% | 50% | 49% | 0.010 |

| Gestational age 37–41 weeks | 4% | 82% | 85% | 84% | 84% | 85% | 84% | 0.251 |

| Birth weight ≥4000g | 0% | 8% | 7% | 8% | 7% | 8% | 9% | 0.522 |

| Male | 0% | 58% | 57% | 56% | 56% | 57% | 56% | 0.300 |

| Death in hospital | 6% | 97% | 98% | 97% | 97% | 97% | 98% | 0.933 |

| Death in 1st hour after birth | 8% | 12% | 11% | 9% | 11% | 11% | 13% | 0.208 |

| Death in the 1st 24h after birth | 0% | 72% | 70% | 73% | 72% | 71% | 71% | 0.568 |

| Death in public hospital | 8% | 72% | 77% | 74% | 68% | 69% | 68% | <0.001 |

| Death in a state capital | 0% | 26% | 28% | 23% | 27% | 24% | 25% | 0.066 |

| Mother lives in the countryside but death in the capital | 0% | 12% | 11% | 11% | 13% | 12% | 12% | 0.235 |

| Death in the city of maternal residence | 0% | 62% | 59% | 59% | 57% | 58% | 56% | <0.001 |

| Meconium aspiration syndrome | 0% | 34% | 36% | 38% | 41% | 40% | 41% | <0.001 |

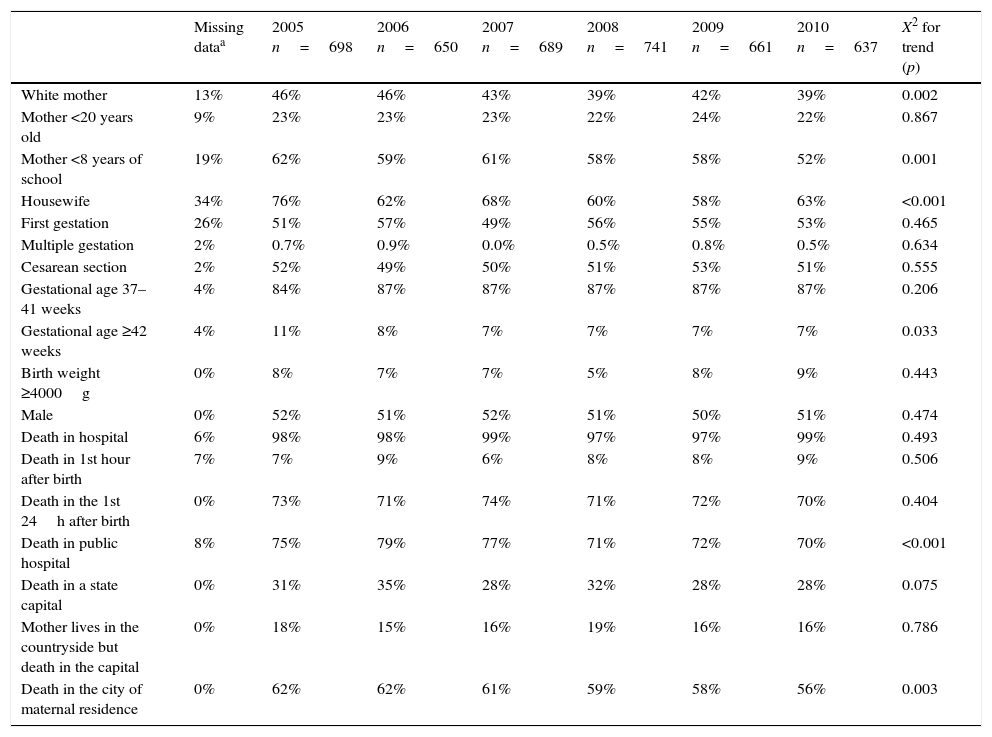

The characteristics of the 4076 infants weighing ≥2500g without malformations who had an early neonatal death associated with meconium aspiration syndrome according to year of death are shown in Table 2. The contribution of the North and Northeast Brazilian regions to these deaths increased from 48% in 2005 to 55% in 2010 (p=0.010). Cesarean section was performed more frequently in infants who had an early neonatal death associated with meconium aspiration syndrome when compared with the total live births10 (51% vs. 48%; p<0.001), especially in the North (49% vs. 47%; p<0.001), Northeast (43% vs. 38%; p<0.001), and Southeast (59% vs. 55%; p<0.001) regions of the country. Neonatal hospital care was equally available in infants who had an early neonatal death associated with meconium aspiration syndrome when compared with the total live births10 (98% vs. 98%; p=0.22), but availability of neonatal hospital care was higher in infants who died with meconium aspiration syndrome when compared with the total live births in the North (97% vs. 92%; p<0.001) and Northeast (98% vs. 96%; p=0.008) regions.

Characteristics of the 4076 early neonatal deaths associated with meconium aspiration syndrome in infants with birth weight ≥2500g without malformations, according to year of death.

| Missing dataa | 2005 n=698 | 2006 n=650 | 2007 n=689 | 2008 n=741 | 2009 n=661 | 2010 n=637 | X2 for trend (p) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White mother | 13% | 46% | 46% | 43% | 39% | 42% | 39% | 0.002 |

| Mother <20 years old | 9% | 23% | 23% | 23% | 22% | 24% | 22% | 0.867 |

| Mother <8 years of school | 19% | 62% | 59% | 61% | 58% | 58% | 52% | 0.001 |

| Housewife | 34% | 76% | 62% | 68% | 60% | 58% | 63% | <0.001 |

| First gestation | 26% | 51% | 57% | 49% | 56% | 55% | 53% | 0.465 |

| Multiple gestation | 2% | 0.7% | 0.9% | 0.0% | 0.5% | 0.8% | 0.5% | 0.634 |

| Cesarean section | 2% | 52% | 49% | 50% | 51% | 53% | 51% | 0.555 |

| Gestational age 37–41 weeks | 4% | 84% | 87% | 87% | 87% | 87% | 87% | 0.206 |

| Gestational age ≥42 weeks | 4% | 11% | 8% | 7% | 7% | 7% | 7% | 0.033 |

| Birth weight ≥4000g | 0% | 8% | 7% | 7% | 5% | 8% | 9% | 0.443 |

| Male | 0% | 52% | 51% | 52% | 51% | 50% | 51% | 0.474 |

| Death in hospital | 6% | 98% | 98% | 99% | 97% | 97% | 99% | 0.493 |

| Death in 1st hour after birth | 7% | 7% | 9% | 6% | 8% | 8% | 9% | 0.506 |

| Death in the 1st 24h after birth | 0% | 73% | 71% | 74% | 71% | 72% | 70% | 0.404 |

| Death in public hospital | 8% | 75% | 79% | 77% | 71% | 72% | 70% | <0.001 |

| Death in a state capital | 0% | 31% | 35% | 28% | 32% | 28% | 28% | 0.075 |

| Mother lives in the countryside but death in the capital | 0% | 18% | 15% | 16% | 19% | 16% | 16% | 0.786 |

| Death in the city of maternal residence | 0% | 62% | 62% | 61% | 59% | 58% | 56% | 0.003 |

This study found that 10,675 infants weighing ≥2500g without malformations died within six days after birth due to perinatal asphyxia; the burden of these deaths per day decreased from 5.6 in 2005 to 4.2 in 2010. Despite the decreasing mortality ratios in all regions of the country, the North and Northeast Brazilian regions presented the greatest burden of deaths. The majority of these deaths occurred in the first day of life. Perinatal asphyxia contributed to 40% of all neonatal Brazilian deaths of low-risk neonates in the study period. Notably, 40% of deaths associated with asphyxia in this group of infants occurred in a hospital located in a different municipality than the maternal residence. Among the 10,675 early deaths of infants weighing ≥2500g without malformations and with asphyxia, 4076 (38%) had a diagnosis of meconium aspiration syndrome in one of the fields of the death certificate, with a 19% increase in meconium aspiration syndrome attributable to early neonatal deaths in 2010 when compared with 2005. This study adds to the available information, on one hand, that perinatal asphyxia accounts for twice (1.86–2.06 times) the number of early deaths of non-low birth weight infants in the country when compared with that reported by the Brazilian Ministry of Health.10 On the other hand, this is the first report of the burden of meconium aspiration syndrome to early neonatal deaths, since official health statistics do not isolate this condition from other neonatal aspiration syndromes as a cause of death. It should be noted that 2100 neonates who died of meconium aspiration syndrome did not have any ICD-10 code related to intrauterine hypoxia or birth asphyxia.

There was a reduction in perinatal asphyxia-related early neonatal deaths from 0.81 to 0.61 per 1000 live births weighing ≥2500g without malformations throughout the study period. This decrease was a result of multiple factors. The primary forces that likely drove the index down include the socioeconomic and demographic changes, with economic growth, reduction in income disparities, urbanization, improved education of women, and decreased fertility rates.14,15 From 2003 to 2008, there was a reduction in inequalities in infant and child mortalities at the individual level, according to maternal education and household income per capita in Brazil.16 Data of all Brazilian live births show that, during the study period (2005–2010), the proportion of adolescent mothers decreased from 21.8% to 19.3%, the frequency of mothers with less than eight years of school also decreased from 48.5% to 34.1%, and hospital births increased from 97.1% to 98.1%.10 In the present study, despite the fact that it covered only early neonatal deaths, the frequency of mothers with less than eight years of education decreased from 64% to 53% from 2005 to 2010, and the frequency of mothers who are part of the workforce increased from 31% to 38% in the same period. It should be noted that Brazil experiences extreme regional differences, especially in social indicators, such as health, infant mortality, and nutrition. The richer South and Southeast regions present better indicators than the North and Northeast.8 This situation is shown in Fig. 1A, which indicates that perinatal asphyxia-related early neonatal deaths in infants weighing ≥2500g without malformations were two times higher in the North and Northeast when compared with the South and Southeast regions of Brazil.

Progress in neonatal survival should include workforce planning to increase the numbers and upgrade specific skills for care at birth.17 In China, policy changes permitted midwives to initiate resuscitation and required resuscitation training for licensure. From 2003 to 2008, over 110,659 professionals received resuscitation training in 322 representative hospitals. Perinatal asphyxia-related deaths in the delivery room decreased from 0.75 to 0.34 per 1000 in this period.18 The large-scale education program aimed at improving the skills of providers, the Brazilian Neonatal Resuscitation Program, may have contributed to the reduction in perinatal asphyxia-related early neonatal deaths of Brazilian infants weighing ≥2500g without malformations from 2005 to 2010.19 This program trained over 75,000 providers who work in the delivery rooms using a network of more than 800 instructors in all Brazilian states since 1994 according to guidelines based on the best available global evidence and updated every five years.20–22

A review of studies demonstrated that meconium-stained amniotic fluid occurs in 13% of pregnancies and that aspiration syndrome occurs in 4% of those born with meconium-stained fluid, with a mortality rate of 10 per 100,000 live births.23 The mortality ratios attributed to meconium aspiration syndrome ranged from 1 to 5 per 100,000 live births in developed countries in the last decade.24,25 In Brazil, from 2005 to 2010, the meconium aspiration syndrome-specific early neonatal mortality ratio in infants weighing ≥2500g without malformations was 23.3 per 100,000 live births, which is four to 23 times higher than those previously reported. Despite the decrease in perinatal asphyxia-related early neonatal deaths in the present series, not only did the deaths associated with meconium aspiration syndrome not decrease, but also their contribution to perinatal asphyxia-related early neonatal deaths increased from 34% in 2005 to 41% in 2010. It is noteworthy that this finding occurred despite the astonishing increasing rates of cesarean section in Brazil from 43.3% in 2005 to 52.3% in 2010.10 It may be speculated whether surgical deliveries and neonatal hospital care were not available for infants who died with meconium aspiration syndrome, but the present results indicate that this was not the case. In North and Northeast regions, in which the highest burden of meconium aspiration syndrome on early neonatal mortality was observed (Fig. 1B), the availability of cesarean delivery and neonatal hospital care was even higher in the studied infants when compared with all live births of the same regions. One of the reasons for this highly specific early neonatal mortality rate is likely related to problems in the organization of the Brazilian perinatal care system, which forces women ready to give birth to approach more than one hospital before being admitted to a maternity ward, occasionally in a municipality distant from their residences.26 Additionally, since secondary referral hospitals, especially in North and Northeast Brazil, do not have neonatal intensive care units, pregnant women are usually transferred when there is evidence of fetal distress, leading to delays in reaching the referral healthcare facility and, consequently, to delays in receiving timely and adequate care.27 According to the present data, among the infants who died from meconium aspiration syndrome, 38% of their mothers lived in a city different from the facility where the infant death occurred in 2005, and this incidence increased to 44% in 2010.

The use of death certificates to obtain data was the primary limitation of the study. Using this source of information brings concerns regarding underreporting of deaths and their causes, because the data are provided by physicians without an objective evaluation of how perinatal asphyxia, in fact, contributed to death. Despite these concerns, the coverage of the Brazilian Mortality Information System is adequate; the reporting of infant mortality increased from approximately 70% in 2005–2007 to 85% in 2008–2010.28 Additionally, because the data were collected from a secondary source, it was not possible to ascertain how many stillbirths were really infants who were born alive, but died in the first minutes after birth. These limitations imply that the burden of perinatal asphyxia on early neonatal deaths of infants weighing ≥2500g without malformations is still heavier than that documented in the present study. Finally, the lack of cross-linkage between birth and death certificates at national level hinders the retrieval of accurate data on some maternal and neonatal characteristics. It is important to stress that the data collection for the study was conducted by pediatricians who are state coordinators of the Brazilian Neonatal Resuscitation Program, which increases their awareness of the local data, helps them to build bridges with the health coordination of the states, and empowers them to discuss local solutions for the high rates of perinatal asphyxia-related neonatal deaths. It must also be stressed that the data refer to deaths between 2005 and 2010 and did not take in account major efforts made by the federal government to improve maternal and neonatal health afterwards. In 2011, the Ministry of Health established the Rede Cegonha (Stork Network), aiming to expand the access to and improve the quality of prenatal care and assistance during delivery, postpartum care, and child care.29 The impact of these actions may have decreased neonatal mortality associated with perinatal asphyxia in the following years.

A safe birth and healthy start in life are the heart of human capital and economic progress.4,30 This study demonstrated that early neonatal mortality rates due to perinatal asphyxia of infants in the better spectrum of birth weight and without congenital malformations are still high, and meconium aspiration syndrome plays a major role. The results of this study may help to enhance national health planning by identifying and overcoming bottlenecks in the maternal and neonatal care to improve newborn survival.

FundingFundação Sociedade Brasileira de Pediatria funded the software for data entry, the professionals that entered the data in the database, and the English translation of the manuscript by American Journal Experts. Fundação Sociedade Brasileira de Pediatria did not have any role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; nor in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. None of the authors were paid to write this manuscript.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The authors would like to thank the State Coordinators of Brazilian Neonatal Resuscitation Program from 2005 to 2012, the State Health Departments, and the Fundação SEADE (Processo Unifesp 23089000057/2014-95) for data collection in each federative unit of Brazil. The authors would also like to thank the Brazilian Pediatric Society for the continuous support to the Neonatal Resuscitation Program.

Please cite this article as: Almeida MF, Kawakami MD, Moreira LM, Santos RM, Anchieta LM, Guinsburg R. Early neonatal deaths associated with perinatal asphyxia in infants ≥2500g in Brazil. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2017;93:576–84.

Study conducted at Sociedade Brasileira de Pediatria, Programa de Reanimação Neonatal, São Paulo, SP, Brazil.