To investigate the occurrence of infectious morbidities according to day care attendance during the first year of life.

MethodsThis was a cross-sectional analysis of data from the 12-month follow-up of a medium-sized city birth cohort from children born in 2015, in the Southern Brazil. Main exposure variables were day care attendance from 0 to 11 months of age, type of day care center (public or private), and age at entering day care. Health outcomes were classified as follows: “non-specific respiratory symptoms,” “upper respiratory tract infection,” “lower respiratory tract infection,” “flu/cold,” “diarrhea,” or “no health problem,” considering the two weeks prior to the interview administered at 12 months of life. Associations were assessed using Poisson regression adjusted by demographic, behavioral, and socioeconomic variables.

ResultsThe sample included 4018 children. Day care attendance was associated with all classifications of health outcomes mentioned above, except for flu/cold. These were stronger among children who entered day care at an age closer to the outcome time-point. An example are the results for lower respiratory tract infection and diarrhea, with adjusted prevalence ratios of 2.79 (95% CI: 1.67–4.64) and 2.04 (95% CI: 1.48–2.82), respectively, for those who entered day care after 8 months of age when compared with those who never attended day care.

ConclusionsThe present study consistently demonstrated the association between day care attendance and higher occurrence of infectious morbidities and symptoms at 12 months of life. Hence, measures to prevent infectious diseases should give special attention to children attending day care centers.

Investigar a ocorrência de morbidades infecciosas de acordo com a frequência em creches durante o primeiro ano de vida.

MétodosEsta foi uma análise transversal dos dados de uma coorte de nascimento, em uma cidade de tamanho médio, na visita aos 12 meses de idade de crianças nascidas em 2015 no Sul do Brasil. As principais variáveis de exposição foram frequência em creches de zero aos 11 meses de idade, tipo de creche (pública ou particular) e idade ao entrar na creche. Os resultados de saúde foram classificados como: “sintomas respiratórios não específicos”, “infecção do trato respiratório superior”, “infecção do trato respiratório inferior”, “gripe/resfriado”, “diarreia” ou “nenhum problema de saúde”, considerando as duas semanas anteriores à entrevista feita aos 12 meses de vida da criança. As associações foram avaliadas com a regressão de Poisson ajustada pelas variáveis demográficas, comportamentais e socioeconômicas.

ResultadosA amostra incluiu 4.018 crianças. O ato de frequentar creches foi associado a todas as classificações de resultados de saúde mencionados, exceto gripe/resfriado. Esses resultados foram mais fortes entre as crianças que começaram a frequentar creches em uma idade mais próxima ao ponto de tempo do resultado. Um exemplo são os resultados para infecção do trato respiratório inferior e diarreia, índice de prevalência ajustado de 2,79 (IC de 95%: 1,67–4,64) e 2,04 (IC de 95%: 1,48–2,82), respectivamente, naqueles que ingressaram nas creches após os oito meses de idade, em comparação com aqueles que nunca frequentaram creche.

ConclusõesO presente estudo mostra sistematicamente a associação entre a frequência em creches e a maior ocorrência de morbidades infecciosas e sintomas aos 12 meses de vida da criança. Assim, deve-se dar atenção especial às medidas para prevenir as doenças infecciosas em crianças que frequentes creches.

Due to the current lifestyle of many families, children have been receiving care outside their own homes more often and at younger ages. Thus, day care centers, where children receive care in groups, have become an alternative for care and early learning before school age.

Several factors are associated with the occurrence of infectious morbidities in childhood, such as short duration of breastfeeding, exposure to poor hygiene, and crowded environments with a high number of household residents and/or sharing the bedroom with other adults and/or children, and attendance to places outside home, such as day care centers.1,2

Since transmission of pathogenic agents at an age of great immunological vulnerability is more likely to occur in crowded environments, many studies have been investigating the occurrence of morbidities associated with day care attendance,3–7 as well as alternatives and educational actions to prevent the dissemination of infections.8,9

Discoveries and advances in prevention strategies10 and immunization,10,11 day care providers obtaining considerable knowledge about pathogen transmission, and new strategies in vaccination – mainly flu and pneumococcal vaccination – play a role in an expected decrease in the occurrence of infectious diseases in children. Despite all this, the moment when children enter day care seems to be still related with their first experience with several infectious diseases, such as pneumonia, otitis, flu, and gastroenteritis.12,13

Therefore, the present study aimed to investigate the onset of several types of common childhood morbidities in the follow-up of a cohort at 12 months of age according to day care attendance among the participants of the 2015 Birth Cohort in Pelotas, Southern Brazil.

MethodsThis study conducted a cross-sectional analysis of data from the 12-month follow-up of the 2015 Pelotas Birth Cohort. The cohort started being recruited at the antenatal stage, when all mothers expecting to give birth in 2015 were invited to participate in the study. Afterwards, all hospital births occurring from the first to the last day of 2015 were monitored and children born from mothers living in the urban area of Pelotas were invited to participate and were subsequently followed up at 3 and 12 months of age. At 12 months, all mothers or guardians of cohort participants were contacted for a home visit that involved administering questionnaires, taking anthropometric measures, and performing cognitive tests. Other details on cohort methods, follow-up rates, and flowcharts are available in a previous open access publication.14

The primary exposure variable was day care attendance during the first year of life, defined as children entering day care up to 11 months of life. This information was collected by asking “I would like to know who took care of

Outcome variables were created by grouping the health conditions occurring in the last two weeks prior to the 12-month interview. This maximum recall time was that necessary to maintain the temporal relationship between exposure and outcome.

The questions used to compose outcomes information were about the presence of cough and respiratory difficulties, or diarrhea. If “yes” was answered to any, more details were collected in open-ended questions, including if the child had a medical examination and what the diagnosis was. Therefore, morbidities were classified into “non-specific respiratory symptoms” (reports of cough, coryza, respiratory distress); respiratory infections divided into “upper respiratory tract infection” (otitis, tonsillitis, laryngitis, and sinusitis) and “lower respiratory tract infection” (pneumonia, bronchiolitis, bronchitis, pulmonary infection)15; “flu/cold”; “diarrhea”; or no health condition reported. This last outcome took into account the complete absence of health problems in the period, not only those investigated in this study. All outcomes were grouped into individual dichotomous variables (presence of the outcome – yes/no). The complete versions of the Cohort questionnaires are available online (http://www.epidemio-ufpel.org.br/site/content/coorte_2015-en/questionnaires.php).

All statistical analyses were performed using Stata (Stata Statistical Software: Release 12. College Station, TX, USA). Exposure variables, outcome variables, and covariates were expressed using absolute and relative frequencies. Associations between the occurrence of morbidities and day care attendance in the overall sample and according to type (public/private) and age of beginning day care attendance were assessed using crude and adjusted Poisson regression with robust variance. Poisson regression with robust variance has been used as an alternative to logistic regression and it can estimate prevalence ratios (PRs) in cross-sectional studies with binary outcomes.16 Adjustment variables, defined a priori and included simultaneously in the model, were sex, mother's age (years), and mother's educational level (years of education), gestational age (weeks), smoking during pregnancy (yes/no), family income (minimum wages) (all of them were collected at perinatal follow-up); and total breastfeeding duration (days), total number of household residents, and number of adults and children sharing the bedroom with the participating child (collected at the 12-month follow-up). Results were expressed as PR and their respective 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). P-values <0.05 were considered significant.

The research project of the 2015 Birth Cohort was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the School of Physical Education of Universidade Federal de Pelotas (CAAE 26746414.5.0000.5313) and the informed consent was signed at the beginning of each follow-up.

ResultsThe initial cohort included 4275 newborns (50.6% males) whose mothers agreed to participate in the study, representing 98.7% of eligible live births occurring in Pelotas during 2015. At 12 months, the follow-up rate was 95.4%, totaling 4018 subjects.

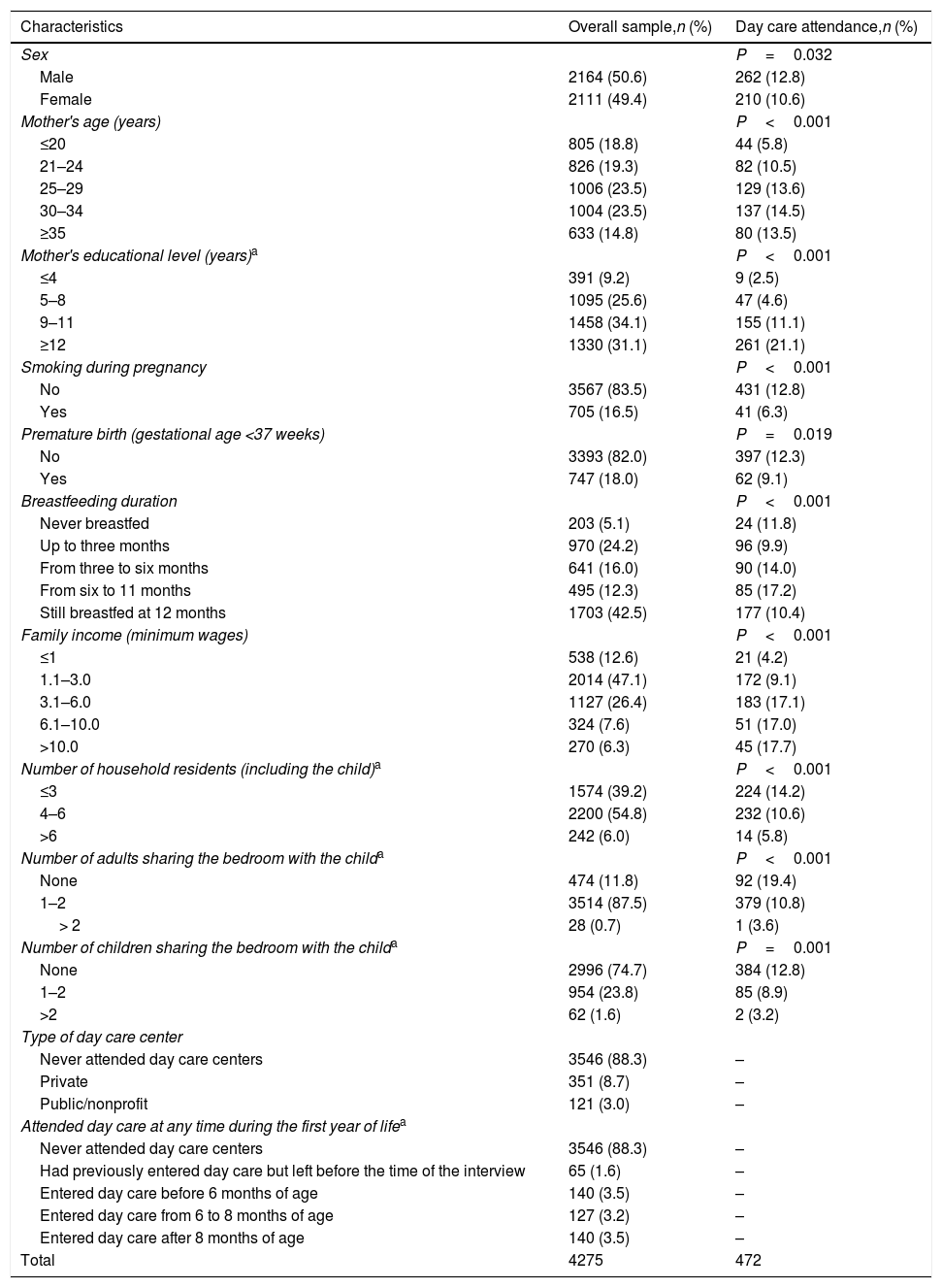

Most mothers were aged from 25 to 35 years at childbirth (47.0%), completed nine years or more of education (65.2%), and 16.5% smoked at some point of their pregnancy. Among children, 18.0% were born before 37 weeks of gestation and 203 (5.1%) had never been breastfed. Most families had a monthly income from one to three minimum wages (47.1%) and had from four to six household residents (54.8%). Overall, 472 (11.7%) children attended day care centers during their first year of life; of these, 351 (74.4%) attended private day care centers, most of which entered day care after six months of age. The highest prevalence of day care use was among mothers more than 25 years old, 12 or more years of schooling, and with children breastfed between 6 and 11 months (Table 1).

Description of the sample of the 2015 Birth Cohort according to variables collected at perinatal and at 12 months of life follow-up, and day care attendance.

| Characteristics | Overall sample,n (%) | Day care attendance,n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | P=0.032 | |

| Male | 2164 (50.6) | 262 (12.8) |

| Female | 2111 (49.4) | 210 (10.6) |

| Mother's age (years) | P<0.001 | |

| ≤20 | 805 (18.8) | 44 (5.8) |

| 21–24 | 826 (19.3) | 82 (10.5) |

| 25–29 | 1006 (23.5) | 129 (13.6) |

| 30–34 | 1004 (23.5) | 137 (14.5) |

| ≥35 | 633 (14.8) | 80 (13.5) |

| Mother's educational level (years)a | P<0.001 | |

| ≤4 | 391 (9.2) | 9 (2.5) |

| 5–8 | 1095 (25.6) | 47 (4.6) |

| 9–11 | 1458 (34.1) | 155 (11.1) |

| ≥12 | 1330 (31.1) | 261 (21.1) |

| Smoking during pregnancy | P<0.001 | |

| No | 3567 (83.5) | 431 (12.8) |

| Yes | 705 (16.5) | 41 (6.3) |

| Premature birth (gestational age <37 weeks) | P=0.019 | |

| No | 3393 (82.0) | 397 (12.3) |

| Yes | 747 (18.0) | 62 (9.1) |

| Breastfeeding duration | P<0.001 | |

| Never breastfed | 203 (5.1) | 24 (11.8) |

| Up to three months | 970 (24.2) | 96 (9.9) |

| From three to six months | 641 (16.0) | 90 (14.0) |

| From six to 11 months | 495 (12.3) | 85 (17.2) |

| Still breastfed at 12 months | 1703 (42.5) | 177 (10.4) |

| Family income (minimum wages) | P<0.001 | |

| ≤1 | 538 (12.6) | 21 (4.2) |

| 1.1–3.0 | 2014 (47.1) | 172 (9.1) |

| 3.1–6.0 | 1127 (26.4) | 183 (17.1) |

| 6.1–10.0 | 324 (7.6) | 51 (17.0) |

| >10.0 | 270 (6.3) | 45 (17.7) |

| Number of household residents (including the child)a | P<0.001 | |

| ≤3 | 1574 (39.2) | 224 (14.2) |

| 4–6 | 2200 (54.8) | 232 (10.6) |

| >6 | 242 (6.0) | 14 (5.8) |

| Number of adults sharing the bedroom with the childa | P<0.001 | |

| None | 474 (11.8) | 92 (19.4) |

| 1–2 | 3514 (87.5) | 379 (10.8) |

| > 2 | 28 (0.7) | 1 (3.6) |

| Number of children sharing the bedroom with the childa | P=0.001 | |

| None | 2996 (74.7) | 384 (12.8) |

| 1–2 | 954 (23.8) | 85 (8.9) |

| >2 | 62 (1.6) | 2 (3.2) |

| Type of day care center | ||

| Never attended day care centers | 3546 (88.3) | – |

| Private | 351 (8.7) | – |

| Public/nonprofit | 121 (3.0) | – |

| Attended day care at any time during the first year of lifea | ||

| Never attended day care centers | 3546 (88.3) | – |

| Had previously entered day care but left before the time of the interview | 65 (1.6) | – |

| Entered day care before 6 months of age | 140 (3.5) | – |

| Entered day care from 6 to 8 months of age | 127 (3.2) | – |

| Entered day care after 8 months of age | 140 (3.5) | – |

| Total | 4275 | 472 |

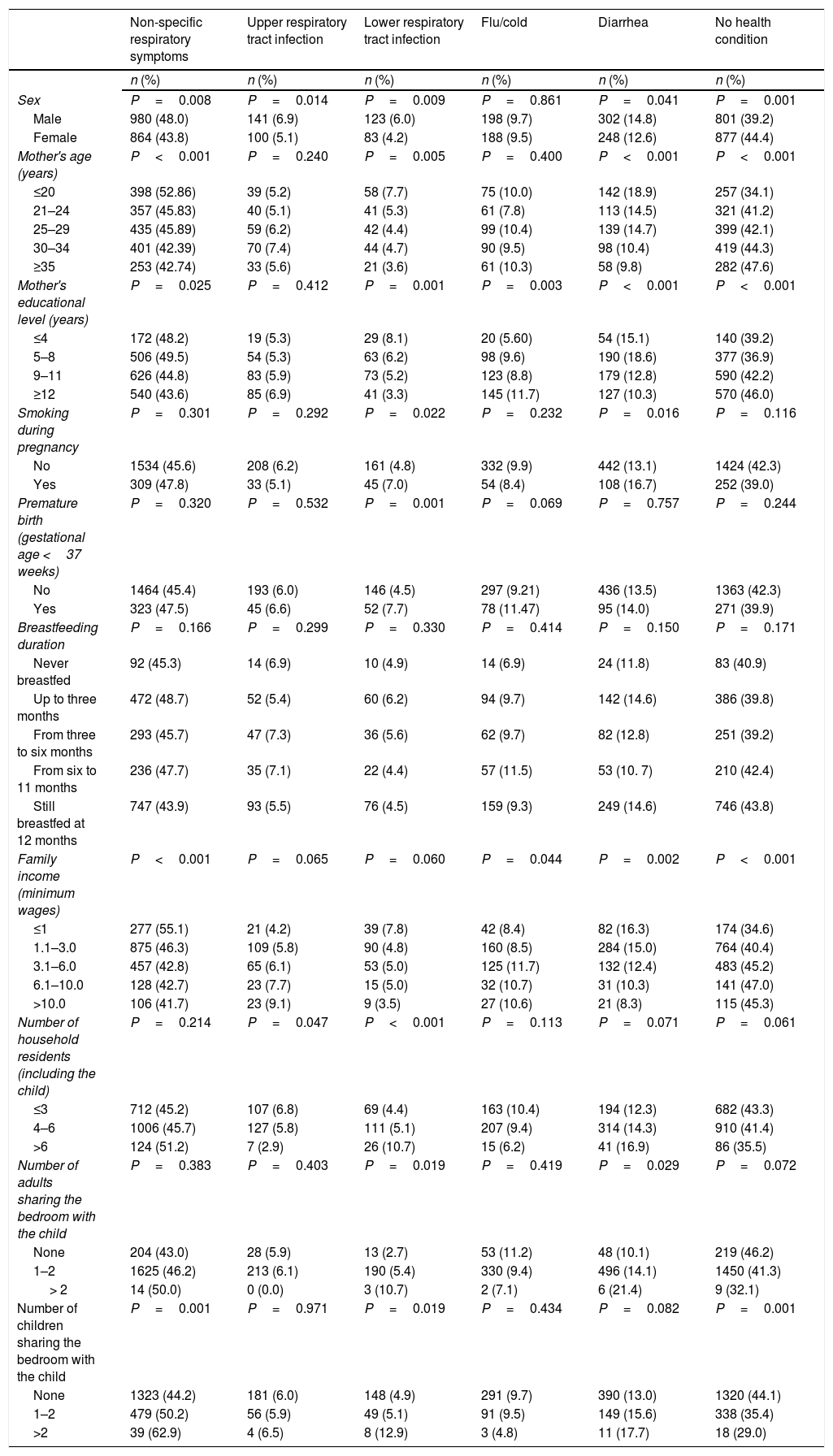

Table 2 shows the outcomes distribution by the covariates. It can be observed that most of the morbidities were more prevalent among boys, children of younger mothers, and crowded households. Regarding socioeconomic factors, the morbidities classified using medical diagnosis, mainly upper respiratory tract infections, did not follow the same distribution pattern as those based only on symptoms, probably due to lack of access to health services. Premature birth and smoking during pregnancy showed higher prevalence of lower respiratory tract infection. Female sex, older mothers, higher maternal education level and family income, breastfeeding more than six months, and lower household crowding seems to be protective characteristics, with higher absence of health problems during the study period.

Description of health conditions in the last two weeks prior to the interview by covariates (n=4018).

| Non-specific respiratory symptoms | Upper respiratory tract infection | Lower respiratory tract infection | Flu/cold | Diarrhea | No health condition | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Sex | P=0.008 | P=0.014 | P=0.009 | P=0.861 | P=0.041 | P=0.001 |

| Male | 980 (48.0) | 141 (6.9) | 123 (6.0) | 198 (9.7) | 302 (14.8) | 801 (39.2) |

| Female | 864 (43.8) | 100 (5.1) | 83 (4.2) | 188 (9.5) | 248 (12.6) | 877 (44.4) |

| Mother's age (years) | P<0.001 | P=0.240 | P=0.005 | P=0.400 | P<0.001 | P<0.001 |

| ≤20 | 398 (52.86) | 39 (5.2) | 58 (7.7) | 75 (10.0) | 142 (18.9) | 257 (34.1) |

| 21–24 | 357 (45.83) | 40 (5.1) | 41 (5.3) | 61 (7.8) | 113 (14.5) | 321 (41.2) |

| 25–29 | 435 (45.89) | 59 (6.2) | 42 (4.4) | 99 (10.4) | 139 (14.7) | 399 (42.1) |

| 30–34 | 401 (42.39) | 70 (7.4) | 44 (4.7) | 90 (9.5) | 98 (10.4) | 419 (44.3) |

| ≥35 | 253 (42.74) | 33 (5.6) | 21 (3.6) | 61 (10.3) | 58 (9.8) | 282 (47.6) |

| Mother's educational level (years) | P=0.025 | P=0.412 | P=0.001 | P=0.003 | P<0.001 | P<0.001 |

| ≤4 | 172 (48.2) | 19 (5.3) | 29 (8.1) | 20 (5.60) | 54 (15.1) | 140 (39.2) |

| 5–8 | 506 (49.5) | 54 (5.3) | 63 (6.2) | 98 (9.6) | 190 (18.6) | 377 (36.9) |

| 9–11 | 626 (44.8) | 83 (5.9) | 73 (5.2) | 123 (8.8) | 179 (12.8) | 590 (42.2) |

| ≥12 | 540 (43.6) | 85 (6.9) | 41 (3.3) | 145 (11.7) | 127 (10.3) | 570 (46.0) |

| Smoking during pregnancy | P=0.301 | P=0.292 | P=0.022 | P=0.232 | P=0.016 | P=0.116 |

| No | 1534 (45.6) | 208 (6.2) | 161 (4.8) | 332 (9.9) | 442 (13.1) | 1424 (42.3) |

| Yes | 309 (47.8) | 33 (5.1) | 45 (7.0) | 54 (8.4) | 108 (16.7) | 252 (39.0) |

| Premature birth (gestational age <37 weeks) | P=0.320 | P=0.532 | P=0.001 | P=0.069 | P=0.757 | P=0.244 |

| No | 1464 (45.4) | 193 (6.0) | 146 (4.5) | 297 (9.21) | 436 (13.5) | 1363 (42.3) |

| Yes | 323 (47.5) | 45 (6.6) | 52 (7.7) | 78 (11.47) | 95 (14.0) | 271 (39.9) |

| Breastfeeding duration | P=0.166 | P=0.299 | P=0.330 | P=0.414 | P=0.150 | P=0.171 |

| Never breastfed | 92 (45.3) | 14 (6.9) | 10 (4.9) | 14 (6.9) | 24 (11.8) | 83 (40.9) |

| Up to three months | 472 (48.7) | 52 (5.4) | 60 (6.2) | 94 (9.7) | 142 (14.6) | 386 (39.8) |

| From three to six months | 293 (45.7) | 47 (7.3) | 36 (5.6) | 62 (9.7) | 82 (12.8) | 251 (39.2) |

| From six to 11 months | 236 (47.7) | 35 (7.1) | 22 (4.4) | 57 (11.5) | 53 (10. 7) | 210 (42.4) |

| Still breastfed at 12 months | 747 (43.9) | 93 (5.5) | 76 (4.5) | 159 (9.3) | 249 (14.6) | 746 (43.8) |

| Family income (minimum wages) | P<0.001 | P=0.065 | P=0.060 | P=0.044 | P=0.002 | P<0.001 |

| ≤1 | 277 (55.1) | 21 (4.2) | 39 (7.8) | 42 (8.4) | 82 (16.3) | 174 (34.6) |

| 1.1–3.0 | 875 (46.3) | 109 (5.8) | 90 (4.8) | 160 (8.5) | 284 (15.0) | 764 (40.4) |

| 3.1–6.0 | 457 (42.8) | 65 (6.1) | 53 (5.0) | 125 (11.7) | 132 (12.4) | 483 (45.2) |

| 6.1–10.0 | 128 (42.7) | 23 (7.7) | 15 (5.0) | 32 (10.7) | 31 (10.3) | 141 (47.0) |

| >10.0 | 106 (41.7) | 23 (9.1) | 9 (3.5) | 27 (10.6) | 21 (8.3) | 115 (45.3) |

| Number of household residents (including the child) | P=0.214 | P=0.047 | P<0.001 | P=0.113 | P=0.071 | P=0.061 |

| ≤3 | 712 (45.2) | 107 (6.8) | 69 (4.4) | 163 (10.4) | 194 (12.3) | 682 (43.3) |

| 4–6 | 1006 (45.7) | 127 (5.8) | 111 (5.1) | 207 (9.4) | 314 (14.3) | 910 (41.4) |

| >6 | 124 (51.2) | 7 (2.9) | 26 (10.7) | 15 (6.2) | 41 (16.9) | 86 (35.5) |

| Number of adults sharing the bedroom with the child | P=0.383 | P=0.403 | P=0.019 | P=0.419 | P=0.029 | P=0.072 |

| None | 204 (43.0) | 28 (5.9) | 13 (2.7) | 53 (11.2) | 48 (10.1) | 219 (46.2) |

| 1–2 | 1625 (46.2) | 213 (6.1) | 190 (5.4) | 330 (9.4) | 496 (14.1) | 1450 (41.3) |

| > 2 | 14 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (10.7) | 2 (7.1) | 6 (21.4) | 9 (32.1) |

| Number of children sharing the bedroom with the child | P=0.001 | P=0.971 | P=0.019 | P=0.434 | P=0.082 | P=0.001 |

| None | 1323 (44.2) | 181 (6.0) | 148 (4.9) | 291 (9.7) | 390 (13.0) | 1320 (44.1) |

| 1–2 | 479 (50.2) | 56 (5.9) | 49 (5.1) | 91 (9.5) | 149 (15.6) | 338 (35.4) |

| >2 | 39 (62.9) | 4 (6.5) | 8 (12.9) | 3 (4.8) | 11 (17.7) | 18 (29.0) |

P-value by the chi-squared test.

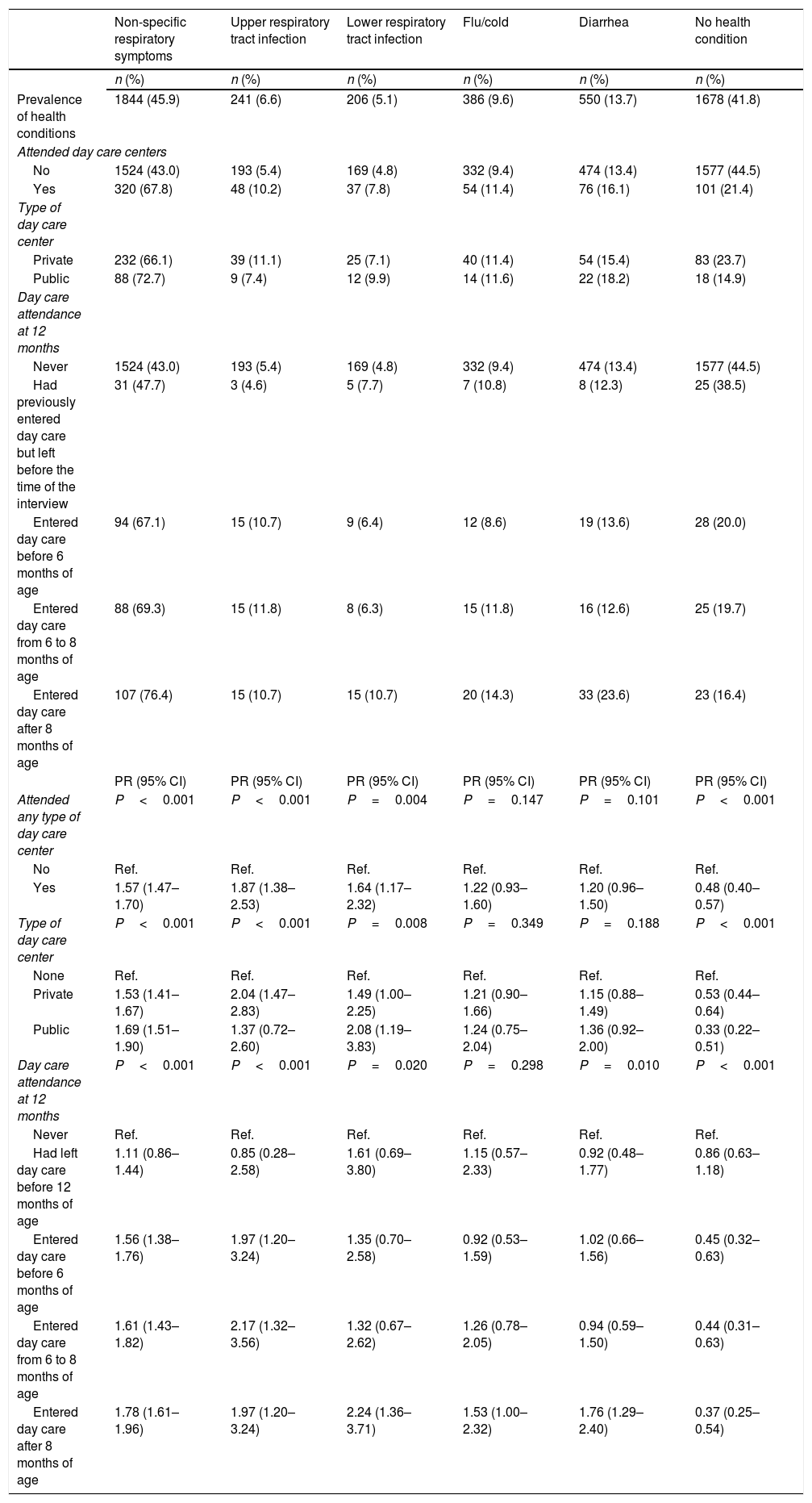

Table 3 shows the absolute and relative frequencies, as well as crude PR, of day care attendance, type of service (public or private), and age at entering day care, according to the presence of health conditions and morbidity groups. The group of non-specific respiratory symptoms was the most prevalent, with 1844 children (45.9%), whereas 1678 (41.8%) did not present with any symptom or health condition. Most health conditions were more prevalent among children who attended day care centers compared with those who did not, and the presence of flu or cold was the only condition that was not associated with exposure variables at any age of entering day care.

Associations between health conditions in the last two weeks prior to the interview and day care attendance during the first year of life – crude analysis (n=4018).

| Non-specific respiratory symptoms | Upper respiratory tract infection | Lower respiratory tract infection | Flu/cold | Diarrhea | No health condition | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Prevalence of health conditions | 1844 (45.9) | 241 (6.6) | 206 (5.1) | 386 (9.6) | 550 (13.7) | 1678 (41.8) |

| Attended day care centers | ||||||

| No | 1524 (43.0) | 193 (5.4) | 169 (4.8) | 332 (9.4) | 474 (13.4) | 1577 (44.5) |

| Yes | 320 (67.8) | 48 (10.2) | 37 (7.8) | 54 (11.4) | 76 (16.1) | 101 (21.4) |

| Type of day care center | ||||||

| Private | 232 (66.1) | 39 (11.1) | 25 (7.1) | 40 (11.4) | 54 (15.4) | 83 (23.7) |

| Public | 88 (72.7) | 9 (7.4) | 12 (9.9) | 14 (11.6) | 22 (18.2) | 18 (14.9) |

| Day care attendance at 12 months | ||||||

| Never | 1524 (43.0) | 193 (5.4) | 169 (4.8) | 332 (9.4) | 474 (13.4) | 1577 (44.5) |

| Had previously entered day care but left before the time of the interview | 31 (47.7) | 3 (4.6) | 5 (7.7) | 7 (10.8) | 8 (12.3) | 25 (38.5) |

| Entered day care before 6 months of age | 94 (67.1) | 15 (10.7) | 9 (6.4) | 12 (8.6) | 19 (13.6) | 28 (20.0) |

| Entered day care from 6 to 8 months of age | 88 (69.3) | 15 (11.8) | 8 (6.3) | 15 (11.8) | 16 (12.6) | 25 (19.7) |

| Entered day care after 8 months of age | 107 (76.4) | 15 (10.7) | 15 (10.7) | 20 (14.3) | 33 (23.6) | 23 (16.4) |

| PR (95% CI) | PR (95% CI) | PR (95% CI) | PR (95% CI) | PR (95% CI) | PR (95% CI) | |

| Attended any type of day care center | P<0.001 | P<0.001 | P=0.004 | P=0.147 | P=0.101 | P<0.001 |

| No | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Yes | 1.57 (1.47–1.70) | 1.87 (1.38–2.53) | 1.64 (1.17–2.32) | 1.22 (0.93–1.60) | 1.20 (0.96–1.50) | 0.48 (0.40–0.57) |

| Type of day care center | P<0.001 | P<0.001 | P=0.008 | P=0.349 | P=0.188 | P<0.001 |

| None | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Private | 1.53 (1.41–1.67) | 2.04 (1.47–2.83) | 1.49 (1.00–2.25) | 1.21 (0.90–1.66) | 1.15 (0.88–1.49) | 0.53 (0.44–0.64) |

| Public | 1.69 (1.51–1.90) | 1.37 (0.72–2.60) | 2.08 (1.19–3.83) | 1.24 (0.75–2.04) | 1.36 (0.92–2.00) | 0.33 (0.22–0.51) |

| Day care attendance at 12 months | P<0.001 | P<0.001 | P=0.020 | P=0.298 | P=0.010 | P<0.001 |

| Never | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Had left day care before 12 months of age | 1.11 (0.86–1.44) | 0.85 (0.28–2.58) | 1.61 (0.69–3.80) | 1.15 (0.57–2.33) | 0.92 (0.48–1.77) | 0.86 (0.63–1.18) |

| Entered day care before 6 months of age | 1.56 (1.38–1.76) | 1.97 (1.20–3.24) | 1.35 (0.70–2.58) | 0.92 (0.53–1.59) | 1.02 (0.66–1.56) | 0.45 (0.32–0.63) |

| Entered day care from 6 to 8 months of age | 1.61 (1.43–1.82) | 2.17 (1.32–3.56) | 1.32 (0.67–2.62) | 1.26 (0.78–2.05) | 0.94 (0.59–1.50) | 0.44 (0.31–0.63) |

| Entered day care after 8 months of age | 1.78 (1.61–1.96) | 1.97 (1.20–3.24) | 2.24 (1.36–3.71) | 1.53 (1.00–2.32) | 1.76 (1.29–2.40) | 0.37 (0.25–0.54) |

PR, prevalence ratio; CI, confidence interval.

P-value: Wald chi-squared test.

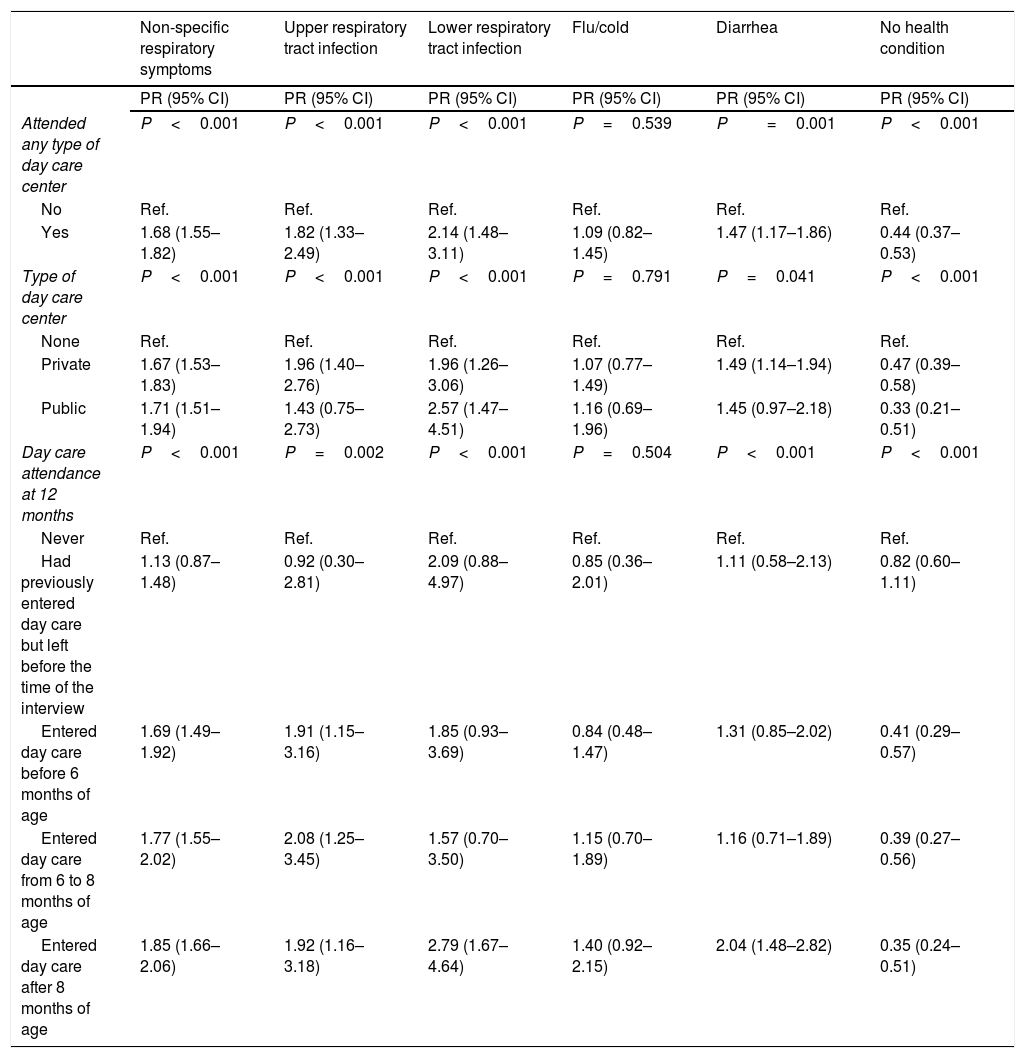

After adjusted analysis (Table 4), lower respiratory tract infection showed PR=2.14 (95% CI: 1.48 – 3.11). Although it was the highest PR among children who attended day care centers compared with those who did not, it cannot be affirmed that this was the highest effect size because the lower limit of the 95% CI overlaps, mainly with the upper respiratory tract infection 95% CI upper limits. Conversely, adjusted PR for not having any health condition in the last two weeks prior to the interview was 0.44 (95% CI: 0.37–0.53), showing that the prevalence of the outcome “no health conditions” was higher among non-exposed children, i.e., those who did not attend day care centers.

Associations between health conditions in the last two weeks prior to the interview and day care attendance during the first year of life – adjusted analysis (n=3891).

| Non-specific respiratory symptoms | Upper respiratory tract infection | Lower respiratory tract infection | Flu/cold | Diarrhea | No health condition | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PR (95% CI) | PR (95% CI) | PR (95% CI) | PR (95% CI) | PR (95% CI) | PR (95% CI) | |

| Attended any type of day care center | P<0.001 | P<0.001 | P<0.001 | P=0.539 | P=0.001 | P<0.001 |

| No | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Yes | 1.68 (1.55–1.82) | 1.82 (1.33–2.49) | 2.14 (1.48–3.11) | 1.09 (0.82–1.45) | 1.47 (1.17–1.86) | 0.44 (0.37–0.53) |

| Type of day care center | P<0.001 | P<0.001 | P<0.001 | P=0.791 | P=0.041 | P<0.001 |

| None | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Private | 1.67 (1.53–1.83) | 1.96 (1.40–2.76) | 1.96 (1.26–3.06) | 1.07 (0.77–1.49) | 1.49 (1.14–1.94) | 0.47 (0.39–0.58) |

| Public | 1.71 (1.51–1.94) | 1.43 (0.75–2.73) | 2.57 (1.47–4.51) | 1.16 (0.69–1.96) | 1.45 (0.97–2.18) | 0.33 (0.21–0.51) |

| Day care attendance at 12 months | P<0.001 | P=0.002 | P<0.001 | P=0.504 | P<0.001 | P<0.001 |

| Never | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Had previously entered day care but left before the time of the interview | 1.13 (0.87–1.48) | 0.92 (0.30–2.81) | 2.09 (0.88–4.97) | 0.85 (0.36–2.01) | 1.11 (0.58–2.13) | 0.82 (0.60–1.11) |

| Entered day care before 6 months of age | 1.69 (1.49–1.92) | 1.91 (1.15–3.16) | 1.85 (0.93–3.69) | 0.84 (0.48–1.47) | 1.31 (0.85–2.02) | 0.41 (0.29–0.57) |

| Entered day care from 6 to 8 months of age | 1.77 (1.55–2.02) | 2.08 (1.25–3.45) | 1.57 (0.70–3.50) | 1.15 (0.70–1.89) | 1.16 (0.71–1.89) | 0.39 (0.27–0.56) |

| Entered day care after 8 months of age | 1.85 (1.66–2.06) | 1.92 (1.16–3.18) | 2.79 (1.67–4.64) | 1.40 (0.92–2.15) | 2.04 (1.48–2.82) | 0.35 (0.24–0.51) |

PR, prevalence ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Adjusted by gender, mother's age (years), mother's education level (years of education), gestational age (weeks), smoking during pregnancy, family income (minimum wages), duration of breastfeeding, number of household residents, and number of adults and children sharing the bedroom with the child. P-value: Wald chi-squared test.

Considering the type of day care center (public or private), respiratory symptoms and lower respiratory tract infection showed higher prevalence in children who attended both types of centers compared with children who did not attend any of them. Those who attended public day care centers showed the higher PR, with an adjusted PR of 1.71 (95% CI: 1.51–1.94) and 2.57 (95% CI: 1.47–4.51) for respiratory symptoms and lower respiratory tract infection, respectively. Adjusted PR for upper respiratory tract infection (PR=1.96; 95% CI: 1.40–2.76) and diarrhea (PR=1.49; 95% CI: 1.14–1.94) were of significance only for children who attended private day care centers when compared to the reference category. There was a lower prevalence of children without health conditions in public day care, followed by private day care centers, and both had a significantly higher PR compared with non-exposed children (Tables 3 and 4).

Those who had previously entered day care but left it before 12 months of age did not show statistically significant difference in prevalence for any of the outcome variables compared with children who had never attended day care centers. Non-specific respiratory symptoms and upper respiratory tract infection, with increased prevalence rates, and absence of health conditions, with decreased prevalence rates, showed significant differences compared with the reference category for all categories of period of day care entry (Table 3).

Therefore, Table 4 shows adjusted PR for risk for developing the morbidities of interest. Based on PR according to the age at entering day care, it ranged from 69% (95% CI: 49–92%) to 108% (95% CI: 25–245%). Children who entered day care before 6 months of age showed the lowest risk for respiratory symptoms, whereas those who entered day care from 6 to 8 months and still attended day care in the moment of the interview showed the highest risk for upper respiratory tract infection compared with the reference category (never attended day care centers). This result considers the outcomes that were associated with day care attendance in more than one category of age at entering day care. Conversely, lower respiratory tract infection and diarrhea showed significantly higher prevalence only among children who entered day care at a period closer to the outcome time point, i.e., after 8 months of age – adjusted PR=2.79 (95% CI: 1.67–4.64) and 2.04 (95% CI: 1.48–2.82) for lower respiratory tract infection and diarrhea, respectively.

DiscussionThis study showed an association between day care attendance and the occurrence of infectious morbidities and symptoms, and this association was maintained after adjustment for several confounding factors that are associated with a greater occurrence of infectious morbidities. Such association is present in all morbidity and symptom groups, except for flu/cold, and is more significant in children who entered day care more recently (after 8 months of age). There was also a linear descending trend for the variable “no health conditions” according to age at entering day care, showing that children who entered day care early seem to have better immunity at 12 months of age.

Pathogens causing diarrhea are usually transmitted through contaminated food or water, direct interpersonal contact, or direct contact with contaminated feces. Poor hygiene and improper handling practices are associated with high levels of bacterial contamination.17 Conversely, microorganisms causing respiratory infections are transmitted through contaminated hands and environments, through direct contact with respiratory secretions, and through the air.7,10 In the city where the study was conducted, the cold climate during most of the year contributes to children remaining indoors in poorly ventilated environments, thus favoring the transmission of pathogens causing respiratory infections.

Exclusion of ill children from the day care attendance is not a consensus and it is only recommended for specific infectious diseases, such as hepatitis, varicella, tuberculosis, meningitis, cytomegalovirus and streptococcal infection, most of them not related to the objective of this study. For diarrhea, the recommendation is temporary exclusion if the diarrhea has infectious characteristics and if stool is not contained in a diaper, predisposing to contamination. Flu/cold and other respiratory symptoms do not show evidence that exclusion could be effective in preventing dissemination. Pediatricians have a special role in identifying and orienting parents, and day care caregivers in the decision of temporarily excluding the child from day care living, based on the behavior of the child and the risk of spreading the infectious disease to other children and staff.18,19

There is difficulty in comparing studies that assess the association between health conditions and day care attendance. This may be explained by the lack of consensus on how to measure both exposure and outcome measures, and by differences in sample's age range. This situation was reported by Barros in 19997 and is still observed in studies published after this review. Most studies are still conducted in high-income countries1,12,20–23 and literature on the topic is scarce in Brazil.8,24,25 Despite this difficulty in comparing findings from different studies, the vast majority of studies, regardless of their setting, found an association between day care attendance and greater occurrence of the health condition of interest. Another important finding from previous studies was that younger children, such as those included in the present sample, are at greater risk of developing morbidities,7,21,23 thus reinforcing the need for focusing preventive measures on this age group.

In the present study, attendance to either public or private day care centers was associated with most outcomes. It is important to highlight that the occurrence of diarrhea in the last two weeks prior to the 12-month interview was found to be a negative confounder. This means that the relative risks strengthen after adjustment, reaching significance for the occurrence of diarrhea among children who attended private day care centers. Although the number of children who attended public day care centers was lower, and significant association was not found, probably due to a lack of statistical power, some previous publications discussed differences between private and public day care related to diarrhea risk. Generally speaking, individuals with lower socioeconomic status, a known risk factor for diarrhea and associated with the use of public services, may live in households with poor infrastructure to implement preventive practices17; the findings suggest that, for this population, day care attendance may not increase the risk for diarrhea and may even be considered a protective environment.7 Conversely, day care centers may be associated with a greater risk for contamination in children with higher socioeconomic status when compared with their households.

This study has some limitations. First, reports of morbidities and symptoms were based on recall of mothers or guardians, with no formal medical diagnosis to confirm the disease. Another limitation is the lack of information on other moments when health conditions occurred, in order to investigate the temporal relationship between health outcomes and age at entering day care. As the outcome questions were only applied at 12-months interview, all the information was standardized in the last two weeks to minimize the recall bias and to ensure that the day care exposure preceded the health problems studied. Diagnoses may also have been influenced by bias of access to health services, which may lead to increased prevalence rates for morbidity groups involving medical diagnosis among children with higher socioeconomic status. As for exposure variables, no information was available on the total number of children attending day care classroom or the amount of time that children spent at the center per day or week. Finally, due to sample stratification according to age at entering day care and type of day care center, some smaller groups may have less statistical power, with large 95% CI, thus reducing the likelihood of detecting statistically significant differences.

Conversely, one of the strengths of the study was its representative population-based sample and its high follow-up rate (less than 5% losses and refusals in the first year), with low random missing information, which prevented selection bias. Questions were standardized, administered by trained interviewers, and answered by mothers (or guardians) in their households, with no differentiation of data collection according to exposures or outcomes of interest. Outcomes covering symptoms or report of no health conditions also minimized the likelihood of biases related to access to healthcare services. Furthermore, the availability of a large information database allows for the control of several confounding factors and increases the reliability of these findings.

In conclusion, the findings of the present study show a consistent association between day care attendance and higher occurrence of morbidities and symptoms at 12 months of age. The results also revealed the importance of the contemporaneous relationship between exposure and outcomes, since children who entered day care more recently showed higher prevalence rates for infectious morbidities and lower prevalence rates for the absence of health conditions. Hence, it can be hypothesized that the burden of most of the health problems occurs in the period closer to when children start to attend day care centers. Therefore, measures to prevent the transmission of infectious diseases must give special attention to children attending day care centers, especially those who are entering into this kind of daily care.

FundingThis article was performed with data from the “Pelotas Birth Cohort study, 2015” (Coorte de Nascimentos de Pelotas, 2015), and carried out by the Postgraduate Program in Epidemiology of Universidade Federal de Pelotas, with the support of Associação Brasileira de Saúde Coletiva (Brazilian Association of Public Health – ABRASCO). The Pelotas Birth Cohort, 2015, was funded by the Wellcome Trust (Grant 095582/Z/11/Z). Funding was also received for specific follow-up from Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) and Fundação de Amparo a Pesquisa do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul (FAPERGS).

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Oliveira PD, Bertoldi AD, Silva BG, Domingues MR, Neumann NA, Silveira MF. Day care attendance during the first 12 months of life and occurrence of infectious morbidities and symptoms. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2019;95:657–66.