Blood pressure (BP) references for Brazilian adolescents are lacking in the literature. This study aims to investigate the normal range of office BP in a healthy, non-overweight Brazilian population of adolescents.

MethodThe Brazilian Study of Cardiovascular Risks in Adolescents (Portuguese acronym “ERICA”) is a national school-based study that included adolescents (aged 12 through 17 years), enrolled in public and private schools, in cities with over 100,000 inhabitants, from all five Brazilian macro-regions. Adolescents’ height and body mass index (BMI) were classified in percentiles according to age and gender, and reference curves from the World Health Organization were adopted. Three consecutive office BP measurements were taken with a validated oscillometric device using the appropriate cuff size. The mean values of the last two readings were used for analysis. Polynomial regression models relating BP, age, and height were applied.

ResultsAmong 73,999 adolescents, non-overweight individuals represented 74.5% (95% CI: 73.3–75.6) of the total, with similar distribution across ages. The majority of the non-overweight sample was from public schools 84.2% (95% CI: 79.9–87.7) and sedentary 54.8% (95% CI: 53.7–55.8). Adolescents reporting their skin color as brown (48.8% [95% CI: 47.4–50.1]) or white (37.8% [95% CI: 36.1–39.5]) were most frequently represented. BP increased by both age and height percentile. Systolic BP growth patterns were more marked in males when compared to females, along all height percentiles. The same pattern was not observed for diastolic BP.

ConclusionsBlood pressure references by sex, age, and height percentiles for Brazilian adolescents are provided.

Referências de pressão arterial (PA) para adolescentes brasileiros estão ausentes na literatura. Este estudo tem como objetivo investigar a variação normal da pressão arterial no consultório em uma população brasileira saudável de adolescentes sem sobrepeso.

MétodoO Estudo dos Riscos Cardiovasculares em Adolescentes (ERICA) é um estudo brasileiro, de âmbito nacional e de base escolar, que incluiu adolescentes (12 a 17 anos) matriculados em escolas públicas e privadas, em cidades com mais de 100.000 habitantes, de todas as cinco macrorregiões brasileiras. A altura e o índice de massa corporal (IMC) dos adolescentes foram classificados em percentis de acordo com a idade e o sexo, sendo adotadas as curvas de referência da Organização Mundial de Saúde. Foram realizadas três medidas consecutivas de PA no consultório com um dispositivo oscilométrico validado, utilizando o manguito de tamanho apropriado. Os valores médios das duas últimas leituras foram utilizados nas análises. Modelos de regressão polinomial relacionando PA, idade e estatura foram aplicados.

ResultadosEntre os 73.999 adolescentes, os indivíduos sem sobrepeso representaram 74,5% (IC95%: 73,3-75,6) do total, com distribuição similar entre as idades. A maior parte da amostra sem sobrepeso originava-se das escolas públicas, com 84,2% (IC95%: 79,9-87,7), e os sedentários 54,8% (IC95%: 53,7-55,8). Os adolescentes que relataram sua cor de pele como parda (48,8% [IC95%: 47,4-50,1]) e branca (37,8%: [IC 95% 36,1-39,5]) foram os mais representados. A PA aumentou tanto com a idade, quanto com o percentil de altura. Os padrões de aumento sistólico da PA foram mais acentuados no sexo masculino quando comparados ao sexo feminino, em todos os percentis de altura. O mesmo padrão não foi observado para a PA diastólica.

ConclusõesSão fornecidas referências de pressão arterial por sexo, idade e percentil de altura para adolescentes brasileiros.

Elevated blood pressure (BP) in children and adolescents is a public health concern worldwide,1 and it is mainly attributable to a remarkable increase in childhood obesity over the past three decades.2 The rate of hypertension (HTN) diagnosis in this age group is estimated to have doubled in the past two decades.3 HTN in the pediatric population is associated with target organ damage4 and moderately tracks into high BP in adulthood.5

Measuring BP during physical examination in pediatric clinical practice was quite unusual until a few years ago.6 Nowadays, the importance of BP measurement in children and adolescents is unquestionable, and the remaining issue is whether to use auscultatory or oscillometric devices.7 The available reference values for defining blood pressure (BP) classes, recommended in most guidelines,7–9 were defined by the auscultatory method. Notwithstanding, the ease of use, the minimization of observer bias or digit preference (which are the common errors associated with the auscultatory method),10 and the recent banning of mercury devices in the European Community will undoubtedly favor the use of oscillometric devices.11 From that perspective, it is convenient to start assembling reference BP data for using oscillometric devices11 in children and adolescents.

Unlike the adult population, there is no childhood hypertension definition based on clinically defined, health-risk-related cut-off levels for increased BP. Instead, age-specific, sex-specific, height-specific, and population-based distributions of BP (90th and 95th percentiles) are used to define normal BP thresholds.12 BP percentiles should not be provided as a function of weight, because relatively high BP would be considered normal merely because a child is overweight.13 The increasing obesity prevalence could result in inappropriate norms for BP if overweight children are included in the normative database.12

Despite the global growing use of oscillometric devices in adolescents, to the authors’ knowledge, there are no available studies assessing pediatric BP references for healthy normal-weight Brazilian adolescents based on oscillometric measurements. Furthermore, no references at all, using any kind of BP measurement devices, are available for Brazilian adolescents.

The present study aims to provide age-, height-, and sex-stratified systolic and diastolic BP reference values in non-overweight Brazilian adolescents using a validated oscillometric device. Further, the study aims to compare the obtained normative values with available international BP percentiles from auscultatory1,13 and oscillometric12,14 devices.

MethodsThis study is part of the Study of Cardiovascular Risk in Adolescents (Portuguese acronym “ERICA”), which is a national, cross-sectional, school-based study, aimed at estimating the prevalence of metabolic syndrome and other cardiovascular risk factors in adolescents aged between 12 and 17 years.

The sample was divided into 32 strata, comprised of 27 capitals of Brazilian States and five cities with more than 100,000 inhabitants from each of the five geographic regions of the country. Stratification was done according to three categories: schools, year/shift class combinations, and classrooms. Thus, the sample was representative at the national and regional, levels, and also at the level of State capitals.

Sample size calculation was based on an expected metabolic syndrome prevalence of 4%,15 a maximum estimation error of 0.9%, a confidence level of 95%, and a design effect of 2.97. The sampling process has been fully described previously.16

ERICA was approved by the Research Ethics Committee (REC) of each participating institution. Adolescents’ were included in the study after signing a consent form and, when required by local the REC, after having an informed consent form signed by their legal guardian.

Information about sex, age, type of school (public or private), skin color, smoking, alcohol consumption, and physical activity were obtained from a self-administered questionnaire using a personal digital assistant (PDA) for data entry.

Adolescents were grouped into six age groups: ≥12 and <13 years; ≥13 and <14 years; ≥14 and <15 years; ≥15 and <16 years; ≥16 and <17 years; ≥17 and <18 years. Skin color included five categories: white, black, brown, yellow, and indigenous, according to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics classification.17 Adolescents who reported smoking on one or more days in the past 30 days were considered smokers, following the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention18 and the Brazilian National Cancer Institute's recommendations.19 Alcohol consumption was defined as a positive answer to the question whether the adolescents consumed alcohol (at least one glass or a dose) within the past 30 days.20

Physical activity level was assessed by the Self-Administered Physical Activity Checklist, which has been previously validated for the Brazilian population.21 The level was determined by the sum of the product of the time spent in each physical activity and the respective frequency. Adolescents who spent less than 300min per week in moderate to vigorous physical activity were considered inactive.22

Height was measured using a calibrated portable stadiometer (Alturexata, Minas Gerais, Brazil) with millimeter resolution and height up to 213cm. Individuals were in full standing position and measurements were taken in duplicate for quality control purposes (if the difference exceeded 0.5cm, height needed to be measured again). Mean value of the two measures was used in the analysis. Height percentiles were classified according to the World Health Organization (WHO) curves.23

Body weight was measured using an electronic scale (Líder, Model P200M, São Paulo, Brazil), with 300kg of capacity and 50g precision.

Waist circumference (WC) was measured using an inelastic measuring tape, with 0.1cm resolution and length of 1.5m (Sanny, São Paulo, Brazil). Individuals were at upright position, with abdomen relaxed at the end of gentle expiration. Measurements were performed horizontally at half distance between the iliac crest and the lower costal margin, and were taken in duplicate for quality control purposes (if the difference exceeded 1cm, WC had to be measured again). The mean value of the two measures was used in the analysis.

Arm length was measured from the acromion to the olecranon using the same measuring tape used for WC measurements. The midpoint on the dorsal (back) surface of the arm was marked with a pen. The participant was asked to relax the arm alongside the body and the measuring tape was placed snugly around the arm at the midpoint mark, keeping the tape horizontal. The tape should not indent the skin.

Nutritional status was classified according to body mass index (BMI), namely the body mass (kg) divided by the square of the body height (m). Reference curves from the WHO were adopted,23 using the BMI-for-age chart, according to sex. The following cut-off points were adopted: Z-score <−3 (very low weight); Z-score ≥−3 and <−2 (low weight); Z-score ≥−2 and ≤1 (normal weight); Z-score>1 and ≤2 (overweight); Z-score>2 (obesity).

Blood pressureBlood pressure measurements were performed following the recommendations of the 4th Report on the Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents, published in 2004.24 The oscillometric device Omron® 705-IT (Omron Healthcare, Bannockburn, USA), previously validated for use in adolescents,25 was used. The appropriate cuff size for the upper right arm was indicated according to arm length measurements.24 Three consecutive BP measures were taken for each individual, with an interval of three minutes between each. The mean values of 2nd and 3rd readings were used in this analysis in order to reduce the impact of reactivity on the blood pressure (higher first reading).26

Statistical analysesStatistical analyses took into account the complex sampling that considers all variability sources of the ERICA sample.16 The sampling weight was calculated by the products of the inverse of the probabilities of inclusion in each selection stage, and calibrated by age and sex, considering the estimated number of adolescents enrolled in schools located in the geographic strata included in the study.

Normally distributed variables were expressed as means and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) and categorical variables as proportions and 95% CI.

For BP percentiles estimations girls were assessed apart from boys. Systolic and diastolic BP were then separately regressed with age (with up to a polynomial of terms: age, age2, age3, and age4) and height Z-score (with up to a polynomial of terms: z, z2, z3, and z4):

where σ denotes the regression residual standard deviation, and zα=0, zα=1.28155, zα=1.64485, zα=2.32635 for the 50th, 90th, 95th, and 99th percentiles, respectively.Regression residual standard deviation was obtained by estimating a residual for each observation followed by calculating a weighted residuals sum of squares, where the applied weight was the survey weight. The square root of this weighted sum of squares was the estimated regression residual standard deviation. The results from polynomial regression models relating blood pressure to age and height Z-score among non-overweight children in the ERICA database are shown in Table S1.

The regression equations were then used to estimate the expected systolic and diastolic BP at specific age and height percentiles. Obtained polynomial coefficients were applied to compute specific 50th, 90th, 95th, and 99th age and height BP percentiles.

The variables were analyzed by using the software Stata 14.0 (StataCorp., College Station, TX, USA) significance level was set as 5%.

ResultsA total of 73,399 adolescents were included in this analysis of the ERICA study (a description of the response rate and the characteristics of people who did or did not take part in the study was provided elsewhere27). From those, 25.5% (95% CI: 24.4–26.6) were identified as being overweight (17.1% [95% CI: 16.3–18.0]) and obese (8.4% [95% CI: 7.9–8.9]), and were excluded from the construction of the BP percentiles (a table describing the overall ERICA sample, non-overweight, and overweight samples is provided as an online supplement – Table S2).

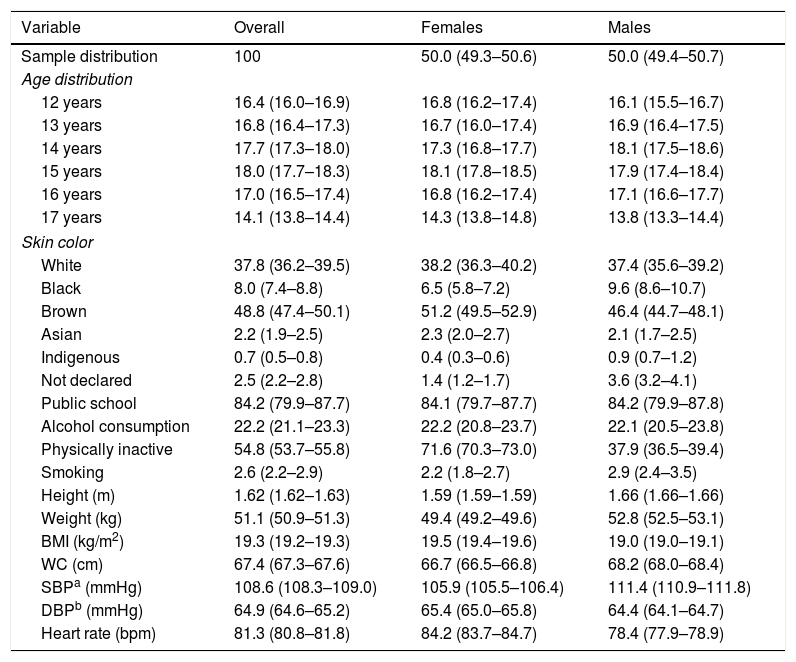

Non-overweight adolescents represented 74.5% (95% CI: 73.3–75.6) of the total sample. Age distribution across the sample varied from 14.1% (95% CI: 13.8–14.4) among those aged 17 years to 18.0% (95% CI: 17.7–18.3) in those 15 years old. The majority of the non-overweight sample was from public schools and was sedentary. Reported skin colors of brown and white were most frequent. When sex was assessed separately, the proportions of blacks and indigenous were higher in males, while the proportion of those who reported themselves as brown was higher in female adolescents. Additionally, the percentage of female adolescents physically inactive was higher than males. The overall description of the sample used to build the reference values for office BP, and its sex stratification is reported in Table 1.

Distribution of non-overweight adolescents by selected variables.

| Variable | Overall | Females | Males |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample distribution | 100 | 50.0 (49.3–50.6) | 50.0 (49.4–50.7) |

| Age distribution | |||

| 12 years | 16.4 (16.0–16.9) | 16.8 (16.2–17.4) | 16.1 (15.5–16.7) |

| 13 years | 16.8 (16.4–17.3) | 16.7 (16.0–17.4) | 16.9 (16.4–17.5) |

| 14 years | 17.7 (17.3–18.0) | 17.3 (16.8–17.7) | 18.1 (17.5–18.6) |

| 15 years | 18.0 (17.7–18.3) | 18.1 (17.8–18.5) | 17.9 (17.4–18.4) |

| 16 years | 17.0 (16.5–17.4) | 16.8 (16.2–17.4) | 17.1 (16.6–17.7) |

| 17 years | 14.1 (13.8–14.4) | 14.3 (13.8–14.8) | 13.8 (13.3–14.4) |

| Skin color | |||

| White | 37.8 (36.2–39.5) | 38.2 (36.3–40.2) | 37.4 (35.6–39.2) |

| Black | 8.0 (7.4–8.8) | 6.5 (5.8–7.2) | 9.6 (8.6–10.7) |

| Brown | 48.8 (47.4–50.1) | 51.2 (49.5–52.9) | 46.4 (44.7–48.1) |

| Asian | 2.2 (1.9–2.5) | 2.3 (2.0–2.7) | 2.1 (1.7–2.5) |

| Indigenous | 0.7 (0.5–0.8) | 0.4 (0.3–0.6) | 0.9 (0.7–1.2) |

| Not declared | 2.5 (2.2–2.8) | 1.4 (1.2–1.7) | 3.6 (3.2–4.1) |

| Public school | 84.2 (79.9–87.7) | 84.1 (79.7–87.7) | 84.2 (79.9–87.8) |

| Alcohol consumption | 22.2 (21.1–23.3) | 22.2 (20.8–23.7) | 22.1 (20.5–23.8) |

| Physically inactive | 54.8 (53.7–55.8) | 71.6 (70.3–73.0) | 37.9 (36.5–39.4) |

| Smoking | 2.6 (2.2–2.9) | 2.2 (1.8–2.7) | 2.9 (2.4–3.5) |

| Height (m) | 1.62 (1.62–1.63) | 1.59 (1.59–1.59) | 1.66 (1.66–1.66) |

| Weight (kg) | 51.1 (50.9–51.3) | 49.4 (49.2–49.6) | 52.8 (52.5–53.1) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 19.3 (19.2–19.3) | 19.5 (19.4–19.6) | 19.0 (19.0–19.1) |

| WC (cm) | 67.4 (67.3–67.6) | 66.7 (66.5–66.8) | 68.2 (68.0–68.4) |

| SBPa (mmHg) | 108.6 (108.3–109.0) | 105.9 (105.5–106.4) | 111.4 (110.9–111.8) |

| DBPb (mmHg) | 64.9 (64.6–65.2) | 65.4 (65.0–65.8) | 64.4 (64.1–64.7) |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 81.3 (80.8–81.8) | 84.2 (83.7–84.7) | 78.4 (77.9–78.9) |

Values given as proportion (95% CI) or mean (95% CI).

BMI, body mass index; WC, waist circumference.

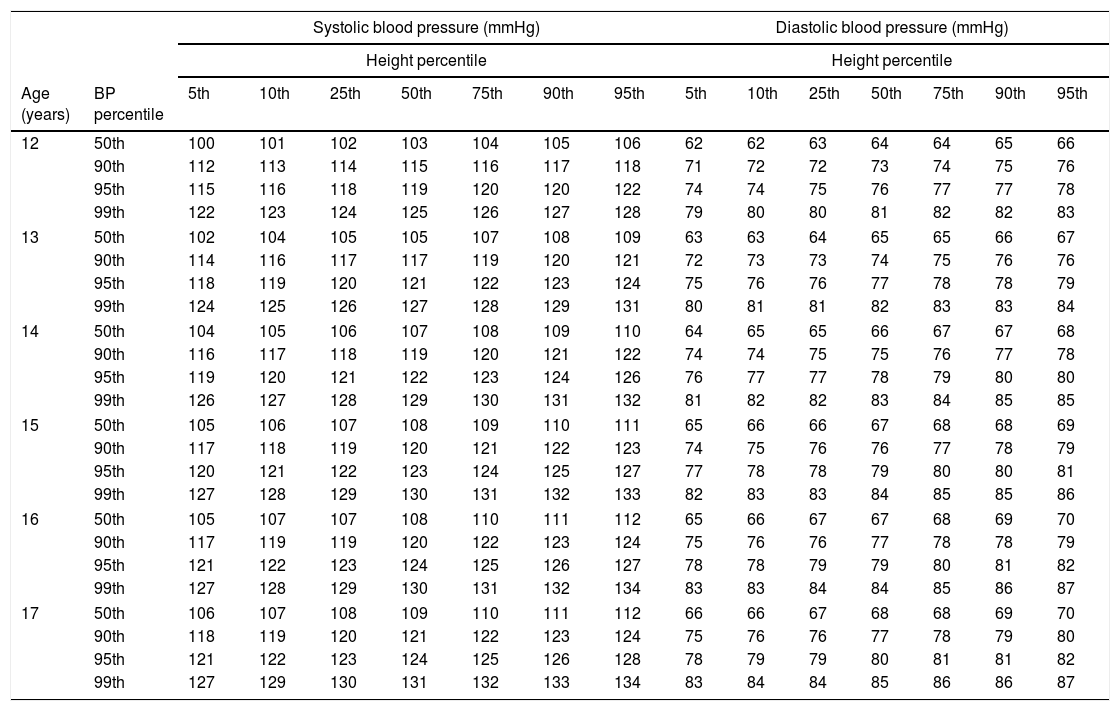

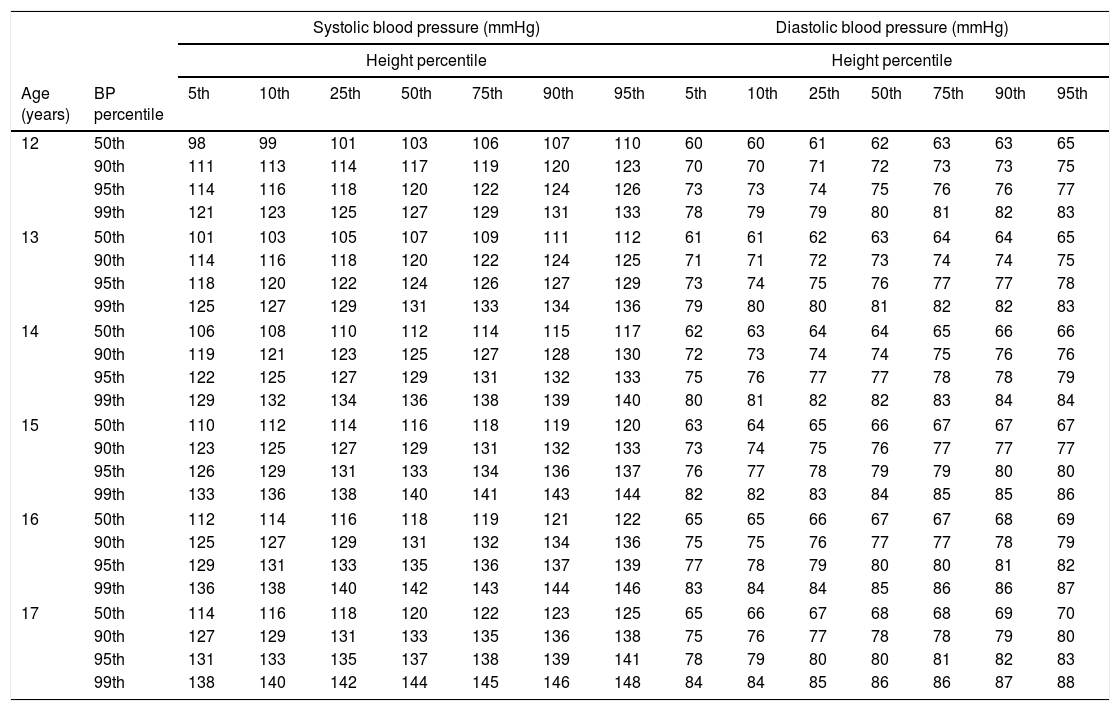

BP percentiles from non-overweight adolescents by age and height are shown in Tables 2 and 3. BP increased in adolescents with both age and height percentiles. Systolic BP growth patterns were more marked in males than in females, along all height percentiles. The same pattern was not observed for diastolic BP.

Office blood pressure values obtained with oscillometric devices in Brazilian female adolescents.

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Height percentile | Height percentile | ||||||||||||||

| Age (years) | BP percentile | 5th | 10th | 25th | 50th | 75th | 90th | 95th | 5th | 10th | 25th | 50th | 75th | 90th | 95th |

| 12 | 50th | 100 | 101 | 102 | 103 | 104 | 105 | 106 | 62 | 62 | 63 | 64 | 64 | 65 | 66 |

| 90th | 112 | 113 | 114 | 115 | 116 | 117 | 118 | 71 | 72 | 72 | 73 | 74 | 75 | 76 | |

| 95th | 115 | 116 | 118 | 119 | 120 | 120 | 122 | 74 | 74 | 75 | 76 | 77 | 77 | 78 | |

| 99th | 122 | 123 | 124 | 125 | 126 | 127 | 128 | 79 | 80 | 80 | 81 | 82 | 82 | 83 | |

| 13 | 50th | 102 | 104 | 105 | 105 | 107 | 108 | 109 | 63 | 63 | 64 | 65 | 65 | 66 | 67 |

| 90th | 114 | 116 | 117 | 117 | 119 | 120 | 121 | 72 | 73 | 73 | 74 | 75 | 76 | 76 | |

| 95th | 118 | 119 | 120 | 121 | 122 | 123 | 124 | 75 | 76 | 76 | 77 | 78 | 78 | 79 | |

| 99th | 124 | 125 | 126 | 127 | 128 | 129 | 131 | 80 | 81 | 81 | 82 | 83 | 83 | 84 | |

| 14 | 50th | 104 | 105 | 106 | 107 | 108 | 109 | 110 | 64 | 65 | 65 | 66 | 67 | 67 | 68 |

| 90th | 116 | 117 | 118 | 119 | 120 | 121 | 122 | 74 | 74 | 75 | 75 | 76 | 77 | 78 | |

| 95th | 119 | 120 | 121 | 122 | 123 | 124 | 126 | 76 | 77 | 77 | 78 | 79 | 80 | 80 | |

| 99th | 126 | 127 | 128 | 129 | 130 | 131 | 132 | 81 | 82 | 82 | 83 | 84 | 85 | 85 | |

| 15 | 50th | 105 | 106 | 107 | 108 | 109 | 110 | 111 | 65 | 66 | 66 | 67 | 68 | 68 | 69 |

| 90th | 117 | 118 | 119 | 120 | 121 | 122 | 123 | 74 | 75 | 76 | 76 | 77 | 78 | 79 | |

| 95th | 120 | 121 | 122 | 123 | 124 | 125 | 127 | 77 | 78 | 78 | 79 | 80 | 80 | 81 | |

| 99th | 127 | 128 | 129 | 130 | 131 | 132 | 133 | 82 | 83 | 83 | 84 | 85 | 85 | 86 | |

| 16 | 50th | 105 | 107 | 107 | 108 | 110 | 111 | 112 | 65 | 66 | 67 | 67 | 68 | 69 | 70 |

| 90th | 117 | 119 | 119 | 120 | 122 | 123 | 124 | 75 | 76 | 76 | 77 | 78 | 78 | 79 | |

| 95th | 121 | 122 | 123 | 124 | 125 | 126 | 127 | 78 | 78 | 79 | 79 | 80 | 81 | 82 | |

| 99th | 127 | 128 | 129 | 130 | 131 | 132 | 134 | 83 | 83 | 84 | 84 | 85 | 86 | 87 | |

| 17 | 50th | 106 | 107 | 108 | 109 | 110 | 111 | 112 | 66 | 66 | 67 | 68 | 68 | 69 | 70 |

| 90th | 118 | 119 | 120 | 121 | 122 | 123 | 124 | 75 | 76 | 76 | 77 | 78 | 79 | 80 | |

| 95th | 121 | 122 | 123 | 124 | 125 | 126 | 128 | 78 | 79 | 79 | 80 | 81 | 81 | 82 | |

| 99th | 127 | 129 | 130 | 131 | 132 | 133 | 134 | 83 | 84 | 84 | 85 | 86 | 86 | 87 | |

BP, blood pressure.

Office blood pressure values obtained with oscillometric devices in Brazilian male adolescents.

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Height percentile | Height percentile | ||||||||||||||

| Age (years) | BP percentile | 5th | 10th | 25th | 50th | 75th | 90th | 95th | 5th | 10th | 25th | 50th | 75th | 90th | 95th |

| 12 | 50th | 98 | 99 | 101 | 103 | 106 | 107 | 110 | 60 | 60 | 61 | 62 | 63 | 63 | 65 |

| 90th | 111 | 113 | 114 | 117 | 119 | 120 | 123 | 70 | 70 | 71 | 72 | 73 | 73 | 75 | |

| 95th | 114 | 116 | 118 | 120 | 122 | 124 | 126 | 73 | 73 | 74 | 75 | 76 | 76 | 77 | |

| 99th | 121 | 123 | 125 | 127 | 129 | 131 | 133 | 78 | 79 | 79 | 80 | 81 | 82 | 83 | |

| 13 | 50th | 101 | 103 | 105 | 107 | 109 | 111 | 112 | 61 | 61 | 62 | 63 | 64 | 64 | 65 |

| 90th | 114 | 116 | 118 | 120 | 122 | 124 | 125 | 71 | 71 | 72 | 73 | 74 | 74 | 75 | |

| 95th | 118 | 120 | 122 | 124 | 126 | 127 | 129 | 73 | 74 | 75 | 76 | 77 | 77 | 78 | |

| 99th | 125 | 127 | 129 | 131 | 133 | 134 | 136 | 79 | 80 | 80 | 81 | 82 | 82 | 83 | |

| 14 | 50th | 106 | 108 | 110 | 112 | 114 | 115 | 117 | 62 | 63 | 64 | 64 | 65 | 66 | 66 |

| 90th | 119 | 121 | 123 | 125 | 127 | 128 | 130 | 72 | 73 | 74 | 74 | 75 | 76 | 76 | |

| 95th | 122 | 125 | 127 | 129 | 131 | 132 | 133 | 75 | 76 | 77 | 77 | 78 | 78 | 79 | |

| 99th | 129 | 132 | 134 | 136 | 138 | 139 | 140 | 80 | 81 | 82 | 82 | 83 | 84 | 84 | |

| 15 | 50th | 110 | 112 | 114 | 116 | 118 | 119 | 120 | 63 | 64 | 65 | 66 | 67 | 67 | 67 |

| 90th | 123 | 125 | 127 | 129 | 131 | 132 | 133 | 73 | 74 | 75 | 76 | 77 | 77 | 77 | |

| 95th | 126 | 129 | 131 | 133 | 134 | 136 | 137 | 76 | 77 | 78 | 79 | 79 | 80 | 80 | |

| 99th | 133 | 136 | 138 | 140 | 141 | 143 | 144 | 82 | 82 | 83 | 84 | 85 | 85 | 86 | |

| 16 | 50th | 112 | 114 | 116 | 118 | 119 | 121 | 122 | 65 | 65 | 66 | 67 | 67 | 68 | 69 |

| 90th | 125 | 127 | 129 | 131 | 132 | 134 | 136 | 75 | 75 | 76 | 77 | 77 | 78 | 79 | |

| 95th | 129 | 131 | 133 | 135 | 136 | 137 | 139 | 77 | 78 | 79 | 80 | 80 | 81 | 82 | |

| 99th | 136 | 138 | 140 | 142 | 143 | 144 | 146 | 83 | 84 | 84 | 85 | 86 | 86 | 87 | |

| 17 | 50th | 114 | 116 | 118 | 120 | 122 | 123 | 125 | 65 | 66 | 67 | 68 | 68 | 69 | 70 |

| 90th | 127 | 129 | 131 | 133 | 135 | 136 | 138 | 75 | 76 | 77 | 78 | 78 | 79 | 80 | |

| 95th | 131 | 133 | 135 | 137 | 138 | 139 | 141 | 78 | 79 | 80 | 80 | 81 | 82 | 83 | |

| 99th | 138 | 140 | 142 | 144 | 145 | 146 | 148 | 84 | 84 | 85 | 86 | 86 | 87 | 88 | |

BP, blood pressure.

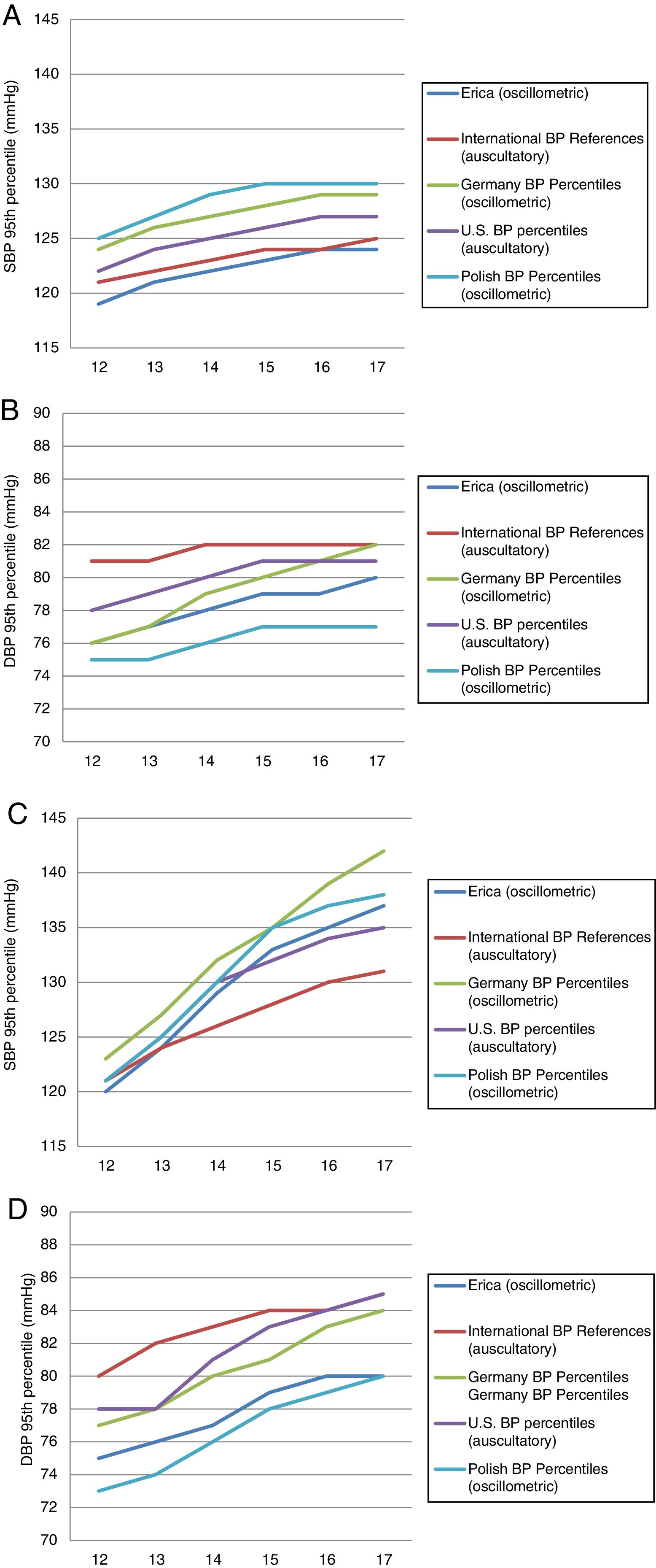

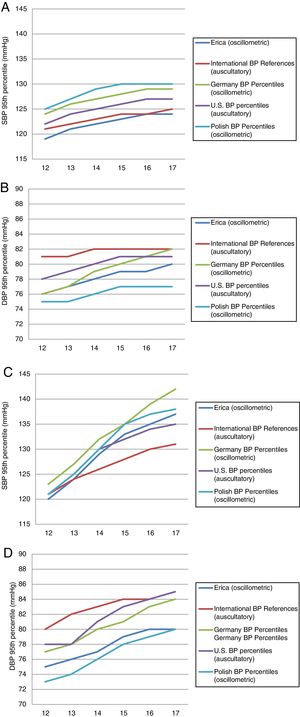

The comparisons of our study's 95th BP percentiles for median height with the available international normative values obtained with two auscultatory and two oscillometric devices are presented in Fig. 1. For females, these systolic BP results were slightly lower than the four compared references. For diastolic BP, the results were between the two other studies conducted using oscillometric devices and lower than the two studies using auscultatory techniques.

For males, this study's systolic BP 95th percentiles for median heights were between the two higher values (using oscillometric devices) and the two lower ones (using auscultatory devices). For diastolic BP in males, the 95th percentiles for median height pattern was similar to that in females (values between studies conducted with oscillometric devices and lower than studies using auscultatory sphygmomanometers).

DiscussionThis study provided sex, age, and height-specific BP percentiles using data from a large, nationally representative population sample of school-aged adolescents in Brazil. To the authors’ knowledge, ERICA is the first Brazilian study providing reference BP values for adolescents using a validated oscillometric device. In addition to being the largest study designed to construct BP percentiles for adolescents conducted heretofore, it used rigorous and standardized methodology for data collection. Because of the strong relationship between BP and overweight/obesity,28 the inclusion of overweight subjects would have raised the threshold for normal BP and, as a result, obesity-related BP elevations would be more difficult to detect.14 To avoid this, overweight adolescents were excluded from the reference population. The same exclusion criterion has been consistently applied in studies assessing BP percentiles in children and adolescents.1,6,12–14,29

Reference values describe a population sample expected to be representative with respect to the parameter evaluated. It remains to be evaluated to what extent the results can be used for other races or continents.30 From that perspective, it is important that other countries or at least regions with similar population characteristics produce their own BP percentile tables for adolescents using oscillometric devices. Until all these tables are available, the results provided in the present study may be used as reference values considering the large sample size and the ethnic heterogeneity of the Brazilian population.31

Blood pressure values obtained with oscillometric devices are considerably higher than those resulting from the auscultatory technique.7 The present study reported lower systolic and diastolic BP percentiles (with the exception of systolic BP in male adolescents) compared with the BP percentiles obtained with auscultatory devices. These results can be explained by the fact that in ERICA the mean of second and third readings was used to compute BP percentiles, which is on average 1–2mmHg lower than the first BP reading.32 This methodology is consistent with the two studies that used oscillometric devices12,14 which were used as references for comparison. Oppositely the studies using auscultatory technique that were compared to these results used either only the first reading13 or a mixture of the first and the mean of the second/third readings.1

National HTN guidelines play an important role in helping the healthcare community to diagnose and treat the disease. The Brazilian Guidelines of Arterial Hypertension,8 which in 2016 reached its seventh edition, is a valued and often revised document. BP references used in the Hypertension in Children and Adolescents chapter of these guidelines were developed using United States data.24 Since the current study is presenting for the first time reference values for office blood pressure in normal weight Brazilian adolescents, consideration should be given to using them in the following versions of the Brazilian hypertension guidelines.

The accuracy of a device is mandatory in any BP measurement method,33 especially considering studies providing reference values for children and adolescents. Oscillometric BP monitors need to be tested in validation studies with specific protocols, and although a considerable number of these devices are available in the market, most of them were not successfully subjected to validation studies.34 The present study used a device that was validated for adolescents’ systolic and diastolic BP using two different international protocols (Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation and European Society of Hypertension International Protocol).25

The European Society of Hypertension guidelines for the management of high BP in children and adolescents (2016)7 proposed that the BP cut-offs for 16 years and older adolescents should no longer be based on the 95th percentile, but on the absolute cut-off used for adults (BP≥140/90mmHg). Alternatively, the Clinical Practice Guideline for Screening and Management of High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents from the American Academy of Pediatrics (2017)9 proposed as a definition of HTN for adolescents aged 12 and 13 years BP values≥95th percentile or ≥130/80mmHg (whichever is lower), and for adolescents aged>13 years, BP values≥130/80mmHg. This difference is probably related to the absence of data to identify a specific level of BP in childhood that results in adverse cardiovascular outcomes in adulthood.9 Because there is no clear consensus in adolescents’ definition of HTN, it was decided to just report the reference values for office blood pressure using oscillometric devices in normal weight adolescents, without calling into question the overall merit of the definition of HTN.

A limitation of this study is that it provides reference values for office BP using oscillometric devices only in non-overweight adolescents (12–17 years range) as the sample selection was restricted to this age group. Normalcy BP references for younger Brazilians are also required and thus studies including this age group (<12 years) are needed.

Although some studies have found an independent effect of sexual maturity on BP,35,36 it has been postulated that the effect of sexual maturity mainly operates through height and body fat.37 Thus, even with the debate about the possible role of sexual maturation on BP, knowledge about the exact influence of sex hormones on BP is rather poor.38 Given that, and the additional objective to make the results more comparable with other adolescents’ BP percentiles tables, the authors did not stratify our results according to pre- and post-puberty.

The recommended method of BP measurement in children and adolescents is still the auscultatory. Oscillometric devices are a suitable alternative for initial screening39 and their increasing use, not only for home BP measurements but also in clinics, justifies efforts to construct BP reference values based on the oscillometric technique with the use of validated devices.12 Although country-specific BP percentiles for adolescents using oscillometric devices have been established in some countries,12,14,29,40 it is important that more countries and regions construct their own percentiles using standardized methodologies. Thus, a globally unified BP reference for defining elevated BP in children and adolescents using oscillometric devices can be developed, which will ultimately enable international comparisons of pediatric HTN prevalence between countries and regions.

In conclusion, the references presented here are, to the authors knowledge, the first Brazilian adolescents’ BP references by age and height based on measurements performed with a validated oscillometric device and following an appropriate methodology for data collection. The proposed reference values were stratified by sex, age, and height, and were not influenced by the prevalence of overweight children in the reference population.

FundingThe ERICA study was supported by the Brazilian Ministry of Health (Science and Technology Department) and the Brazilian Ministry of Science and Technology (Financiadora de Estudos e Projetos/FINEP and Conselho Nacional de Pesquisa/CNPq) (grants FINEP: 01090421, CNPq: 565037/2010-2, 405009/2012-7 and 457050/2013-6).

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Jardim TV, Rosner B, Bloch KV, Kuschnir MC, Szklo M, Jardim PC. Blood pressure reference values for Brazilian adolescents: data from the Study of Cardiovascular Risk in Adolescents (ERICA Study). J Pediatr (Rio J). 2020;96:168–76.