To determine the association between the number of sexual partners and alcohol consumption in adolescents and young schoolchildren.

MethodsThe sample consisted of students from public schools aged 12–24 years who answered the Brazilian version of the Youth Risk Behavior Survey questionnaire. The analysis was performed by multinomial logistic regression model.

Results1275 students were analyzed. For females, having two to five partners was associated with age ≥15 years (OR 14.58) and maternal education up to incomplete high school or lower educational level (OR 3.37). No consumption of alcohol decreased the chances of having more partners by 96%. For males, the associated variables were: age ≥15 years (OR 18.15); having no religion (OR 3.55); age at first dose ≤14 years (OR 3.48). Binge drinking increases the chances of having a higher number of sexual partners.

ConclusionRegardless of the number of partners, binge drinking and age of alcohol consumption onset are risk factors for vulnerable sexual behavior.

Determinar a associação entre número de parceiros sexuais e consumo de bebida alcoólica em adolescentes e jovens escolares.

MétodosA amostra foi composta por estudantes da rede estadual com idade entre 12 e 24 anos, que responderam a versão brasileira do questionário Youth Risk Behavior Survey. A análise foi realizada por modelo de regressão logística multinomial.

ResultadosForam analisados 1.275 estudantes. Para o sexo feminino ter entre dois a cinco parceiros esteve associado com idade ≥15 anos (OR 14,58) e escolaridade materna com ensino médio incompleto ou inferior (OR 3,37). Não fazer uso de bebida alcoólica diminuiu em 96% as chances de ter maior número de parceiros. Para o sexo masculino as variáveis associadas foram: idade ≥15 anos (OR 18,15); ausência de religião (OR 3,55); idade da primeira dose ≤14 anos (OR 3,48). O envolvimento em bebedeira demonstrou mais chances de ter maior número de parceiros sexuais.

ConclusãoIndependente do número de parceiros, a bebedeira e a idade de iniciação alcoólica são fatores de risco para comportamento sexual vulnerável.

Sexual risk behavior is a consequence of practicing unprotected sex1 and of having a higher number of sexual partners, contributing to a greater risk of acquiring sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and the occurrence of unwanted pregnancy.2,3

The first adolescent sexual intercourse is often not planned, being referred to as “it simply happened.”4,5 Early sexual initiation is a concern, as it may be accompanied by STD exposure factors due to the increased number of partners and failure to use condoms.6

Sexual risk behavior does not occur in isolation, as it is associated with alcohol consumption, which acts as a sexual risk indicator.7 Drinking alcohol negatively influences adolescent behavior, resulting in decreased perception and control of the sexual experience.8

In Brazil, studies9,10 have verified that regular alcohol consumption is higher among students who have had sexual intercourse, due to the disinhibition effects caused by its consumption.10 In addition, the use of alcohol in the month and before the last sexual intercourse increase the chances of having multiple sexual partners.11 In this sense, these data demonstrate that alcohol consumption is a matter of concern in this population group. However, studies that address this context are carried out mostly in large cities,12–14 representing a scarcely assessed topic in population of the countryside.

Therefore, information covering other regions can help identify risk groups and patterns, thus allowing the monitoring of adolescent health levels aiming at creating programs and promoting health-oriented policies.

Based on the several negative effects these behaviors can have on adolescents’ lives and on the lack of results on the subject, especially in the assessed area, it was appropriate to carry out the present study, which aimed at establishing the association between the number of sexual partners and alcohol consumption among adolescent students.

MethodsAn epidemiological, cross-sectional, descriptive, analytical, and school-based study was conducted in public (state) elementary and high school institutions in the city of Petrolina, state of Pernanbuco, Brazil, from March to July 2014.

Adolescents that met the following criteria participated in the study: adolescent or young individual (according to the WHO definition) of both genders; able to read and write in the Portuguese language; appropriately enrolled in institutions located in the urban area of Petrolina. Subjects that had a medical diagnosis of neurological disorders or physical condition abnormalities that prevented completion of the tool, those who did not report gender or age, and those who did not adequately fill out the questionnaire were excluded.

The WinPepi program (Calculator Programs for the Health Sciences. Oxford University, USA) was used to quantify the minimum sample size, considering a population of 25,635 students, confidence interval of 95%; maximum tolerable error of 4 percentage points, and sample loss of 20%; and, as this study dealt with different risk behaviors, the prevalence used was 50%, totaling 474 adolescents. A sampling design effect of 2.0 was considered, totaling 948 adolescents; however, 1275 adolescents were evaluated.

All 29 public schools in the urban area were considered eligible; of these, nine were selected, representing 31.03% of the schools. School distribution was carried out by size, after they were classified as small (less than 200 students), medium (200–499 students), or large (500 or more students).15

The schoolchildren and at least one parent or legal guardian (if the individual was aged <18 years) who agreed to participate in the study signed the Term of Agreement and an informed consent forms, respectively.

Binge drinking was defined as consuming five or more doses of alcoholic beverages on a single occasion,8,16–18 and the type of alcoholic beverage user was classified as follows: non-user – never drank alcohol in the lifetime; new user/experimentation – has drunk for 1–19 days in the lifetime; moderate user – 20–99 days, and heavy user – 100 days or more of alcohol intake in the lifetime.3,17,19

A self-administered, structured questionnaire was used, consisting of a socio-economic survey and the risk behavior questionnaire “Youth Risk Behavior Survey” (YRBS), which is a reliable tool,20 whose Brazilian version has been validated.21 The response alternatives to the questions were multiple-choice answers, as shown in the example: “With how many different people have you had sexual intercourse during your lifetime?” with the following possible answers: (a) I have never had sexual intercourse, (b) 1, (c) 2, (d) 3, (e) 4, (f) 5, (g) 6 or more.

For the analysis, the domains on alcohol consumption and sexual behavior were used, comprising questions 38–43 and 57–64, respectively. The Kappa Concordance Index values varied from moderate to substantial for alcohol consumption, ranging from 49.4 to 66.7, and excellent for sexual behavior, with values from 81 to 95.6.21

A pilot study was performed to determine potential limitations. At this stage, the time for tool application and researcher training was measured. The collection took place in a state public school with 80 adolescents. A total of ten trained researchers participated.

Students were accommodated in the classroom and received the questionnaire, and were instructed to hand it back to the researcher after filling it out, which took on average 40min to complete. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Universidade of Pernambuco – UPE and met all provisions of Resolution 466/12 of the National Health Council (CNS) and the Statute of Children and Adolescents.

Data were entered by double entry using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft®, USA) and analyzed using SPSS (IBM Corp. Released 2011. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0, USA). Considering the symmetrical distribution, measures of central tendency and dispersion were used for the continuous variables, or measure of central tendency plus the separatrices for nonparametric distribution. Categorical data were shown as absolute and relative frequencies and possible associations were calculated using bivariate logistic regression models to test the isolated association between the dependent variables and each independent variable, in addition to analyzing the variables that entered the model, exploring the possible confounding factors and identifying the need for statistical adjustment of the analyses.

Multinomial logistic regression was used for the dependent variable: number of sexual partners, with the variables that remained associated with the outcome being demonstrated in the final model adjusted for gender. To express the degree of association between variables, the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were estimated. For multiple end models, variables were selected whose significance p-value was less than 0.20. The p-value was established as p<0.05. Variables whose p-value significance was <0.20 were selected for the multiple final models, considering the value of p<0.05.

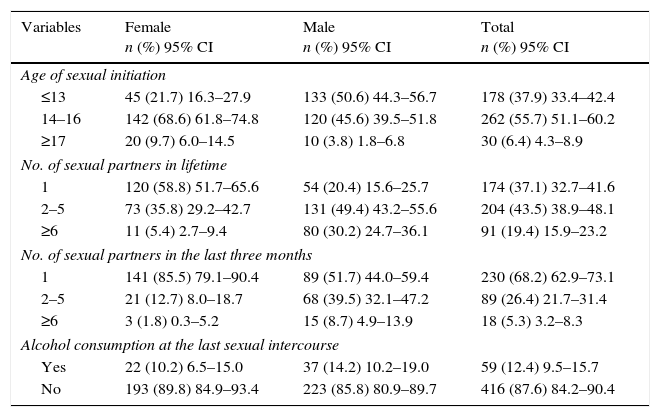

ResultsOf the 1326 students, 51 were excluded, as they failed to fill out the information, and therefore 1275 were included in the analysis. Regarding sexual behavior, 461 (37.0%) reported having already had sexual intercourse. Table 1 shows the sexual behavior distribution of students that reported having an active sex life. Most students had their sexual initiation between 14 and 16 years, had between two to five partners in their lifetime, reported having sexual intercourse with a partner in the last three months, and reported not drinking alcohol during their last sexual intercourse.

Distribution of the sexual behavior of adolescents and young individuals who reported an active sex life. Petrolina, PE, Brazil, 2014.

| Variables | Female n (%) 95% CI | Male n (%) 95% CI | Total n (%) 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age of sexual initiation | |||

| ≤13 | 45 (21.7) 16.3–27.9 | 133 (50.6) 44.3–56.7 | 178 (37.9) 33.4–42.4 |

| 14–16 | 142 (68.6) 61.8–74.8 | 120 (45.6) 39.5–51.8 | 262 (55.7) 51.1–60.2 |

| ≥17 | 20 (9.7) 6.0–14.5 | 10 (3.8) 1.8–6.8 | 30 (6.4) 4.3–8.9 |

| No. of sexual partners in lifetime | |||

| 1 | 120 (58.8) 51.7–65.6 | 54 (20.4) 15.6–25.7 | 174 (37.1) 32.7–41.6 |

| 2–5 | 73 (35.8) 29.2–42.7 | 131 (49.4) 43.2–55.6 | 204 (43.5) 38.9–48.1 |

| ≥6 | 11 (5.4) 2.7–9.4 | 80 (30.2) 24.7–36.1 | 91 (19.4) 15.9–23.2 |

| No. of sexual partners in the last three months | |||

| 1 | 141 (85.5) 79.1–90.4 | 89 (51.7) 44.0–59.4 | 230 (68.2) 62.9–73.1 |

| 2–5 | 21 (12.7) 8.0–18.7 | 68 (39.5) 32.1–47.2 | 89 (26.4) 21.7–31.4 |

| ≥6 | 3 (1.8) 0.3–5.2 | 15 (8.7) 4.9–13.9 | 18 (5.3) 3.2–8.3 |

| Alcohol consumption at the last sexual intercourse | |||

| Yes | 22 (10.2) 6.5–15.0 | 37 (14.2) 10.2–19.0 | 59 (12.4) 9.5–15.7 |

| No | 193 (89.8) 84.9–93.4 | 223 (85.8) 80.9–89.7 | 416 (87.6) 84.2–90.4 |

Note: The total number may differ due to missing values.

95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

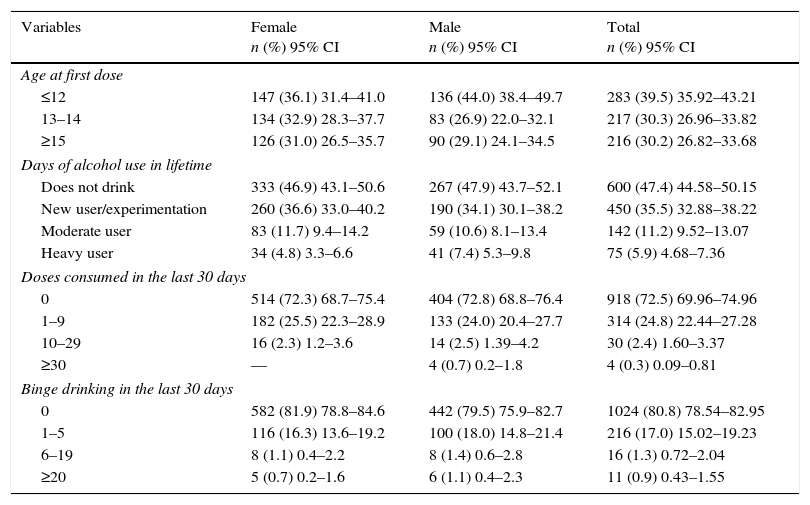

Regarding the adolescents’ profile in relation to alcohol consumption, Table 2 depicts the distribution of variables. It can be observed that most students started drinking at age 12 years or younger, were new users of alcohol, and had not drunk or been involved with binge drinking in the last 30 days.

Distribution of alcohol consumption among adolescents and young individuals. Petrolina, PE, Brazil, 2014.

| Variables | Female n (%) 95% CI | Male n (%) 95% CI | Total n (%) 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at first dose | |||

| ≤12 | 147 (36.1) 31.4–41.0 | 136 (44.0) 38.4–49.7 | 283 (39.5) 35.92–43.21 |

| 13–14 | 134 (32.9) 28.3–37.7 | 83 (26.9) 22.0–32.1 | 217 (30.3) 26.96–33.82 |

| ≥15 | 126 (31.0) 26.5–35.7 | 90 (29.1) 24.1–34.5 | 216 (30.2) 26.82–33.68 |

| Days of alcohol use in lifetime | |||

| Does not drink | 333 (46.9) 43.1–50.6 | 267 (47.9) 43.7–52.1 | 600 (47.4) 44.58–50.15 |

| New user/experimentation | 260 (36.6) 33.0–40.2 | 190 (34.1) 30.1–38.2 | 450 (35.5) 32.88–38.22 |

| Moderate user | 83 (11.7) 9.4–14.2 | 59 (10.6) 8.1–13.4 | 142 (11.2) 9.52–13.07 |

| Heavy user | 34 (4.8) 3.3–6.6 | 41 (7.4) 5.3–9.8 | 75 (5.9) 4.68–7.36 |

| Doses consumed in the last 30 days | |||

| 0 | 514 (72.3) 68.7–75.4 | 404 (72.8) 68.8–76.4 | 918 (72.5) 69.96–74.96 |

| 1–9 | 182 (25.5) 22.3–28.9 | 133 (24.0) 20.4–27.7 | 314 (24.8) 22.44–27.28 |

| 10–29 | 16 (2.3) 1.2–3.6 | 14 (2.5) 1.39–4.2 | 30 (2.4) 1.60–3.37 |

| ≥30 | — | 4 (0.7) 0.2–1.8 | 4 (0.3) 0.09–0.81 |

| Binge drinking in the last 30 days | |||

| 0 | 582 (81.9) 78.8–84.6 | 442 (79.5) 75.9–82.7 | 1024 (80.8) 78.54–82.95 |

| 1–5 | 116 (16.3) 13.6–19.2 | 100 (18.0) 14.8–21.4 | 216 (17.0) 15.02–19.23 |

| 6–19 | 8 (1.1) 0.4–2.2 | 8 (1.4) 0.6–2.8 | 16 (1.3) 0.72–2.04 |

| ≥20 | 5 (0.7) 0.2–1.6 | 6 (1.1) 0.4–2.3 | 11 (0.9) 0.43–1.55 |

Note: The total number may differ due to missing values.

95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

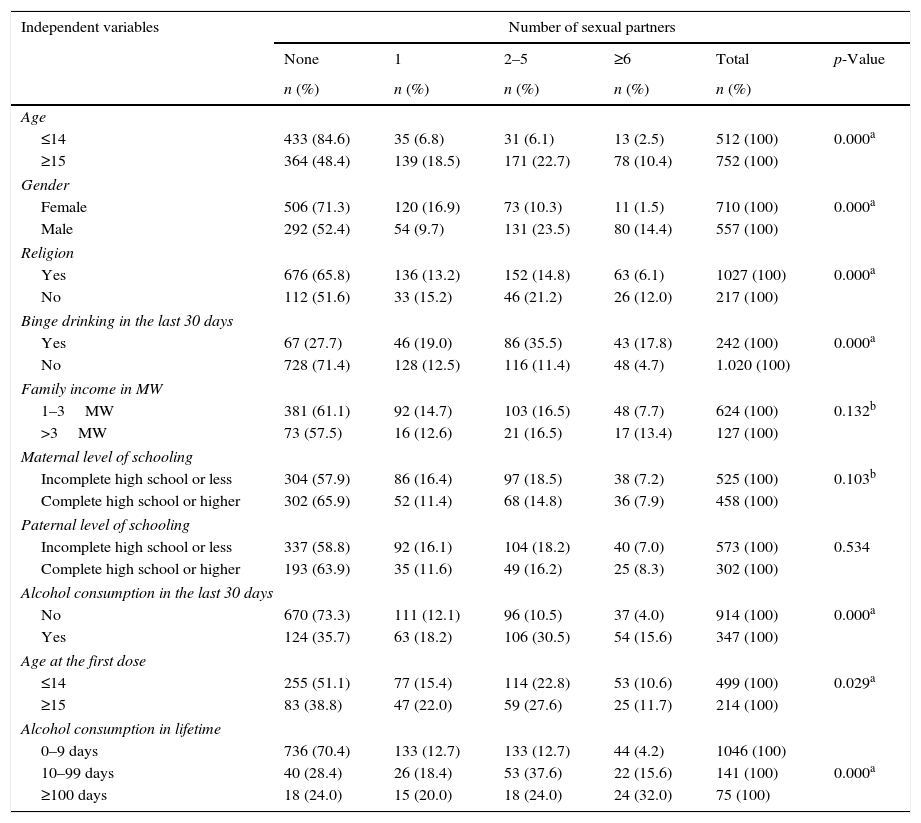

Table 3 shows the association between the number of lifetime sexual partners and the independent variables. The variables that remained in the regression model were age, gender, religion, binge drinking in the last 30 days, family income, maternal level of schooling, alcohol consumption in the last 30 days, and age at first dose.

Association between the number of sexual partners during lifetime and the independent variables in adolescents and young individuals. Petrolina, PE, Brazil, 2014.

| Independent variables | Number of sexual partners | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | 1 | 2–5 | ≥6 | Total | p-Value | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Age | ||||||

| ≤14 | 433 (84.6) | 35 (6.8) | 31 (6.1) | 13 (2.5) | 512 (100) | 0.000a |

| ≥15 | 364 (48.4) | 139 (18.5) | 171 (22.7) | 78 (10.4) | 752 (100) | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 506 (71.3) | 120 (16.9) | 73 (10.3) | 11 (1.5) | 710 (100) | 0.000a |

| Male | 292 (52.4) | 54 (9.7) | 131 (23.5) | 80 (14.4) | 557 (100) | |

| Religion | ||||||

| Yes | 676 (65.8) | 136 (13.2) | 152 (14.8) | 63 (6.1) | 1027 (100) | 0.000a |

| No | 112 (51.6) | 33 (15.2) | 46 (21.2) | 26 (12.0) | 217 (100) | |

| Binge drinking in the last 30 days | ||||||

| Yes | 67 (27.7) | 46 (19.0) | 86 (35.5) | 43 (17.8) | 242 (100) | 0.000a |

| No | 728 (71.4) | 128 (12.5) | 116 (11.4) | 48 (4.7) | 1.020 (100) | |

| Family income in MW | ||||||

| 1–3MW | 381 (61.1) | 92 (14.7) | 103 (16.5) | 48 (7.7) | 624 (100) | 0.132b |

| >3MW | 73 (57.5) | 16 (12.6) | 21 (16.5) | 17 (13.4) | 127 (100) | |

| Maternal level of schooling | ||||||

| Incomplete high school or less | 304 (57.9) | 86 (16.4) | 97 (18.5) | 38 (7.2) | 525 (100) | 0.103b |

| Complete high school or higher | 302 (65.9) | 52 (11.4) | 68 (14.8) | 36 (7.9) | 458 (100) | |

| Paternal level of schooling | ||||||

| Incomplete high school or less | 337 (58.8) | 92 (16.1) | 104 (18.2) | 40 (7.0) | 573 (100) | 0.534 |

| Complete high school or higher | 193 (63.9) | 35 (11.6) | 49 (16.2) | 25 (8.3) | 302 (100) | |

| Alcohol consumption in the last 30 days | ||||||

| No | 670 (73.3) | 111 (12.1) | 96 (10.5) | 37 (4.0) | 914 (100) | 0.000a |

| Yes | 124 (35.7) | 63 (18.2) | 106 (30.5) | 54 (15.6) | 347 (100) | |

| Age at the first dose | ||||||

| ≤14 | 255 (51.1) | 77 (15.4) | 114 (22.8) | 53 (10.6) | 499 (100) | 0.029a |

| ≥15 | 83 (38.8) | 47 (22.0) | 59 (27.6) | 25 (11.7) | 214 (100) | |

| Alcohol consumption in lifetime | ||||||

| 0–9 days | 736 (70.4) | 133 (12.7) | 133 (12.7) | 44 (4.2) | 1046 (100) | |

| 10–99 days | 40 (28.4) | 26 (18.4) | 53 (37.6) | 22 (15.6) | 141 (100) | 0.000a |

| ≥100 days | 18 (24.0) | 15 (20.0) | 18 (24.0) | 24 (32.0) | 75 (100) | |

Chi-squared test.

Note: The total number may differ due to missing values.

MW, minimum wages.

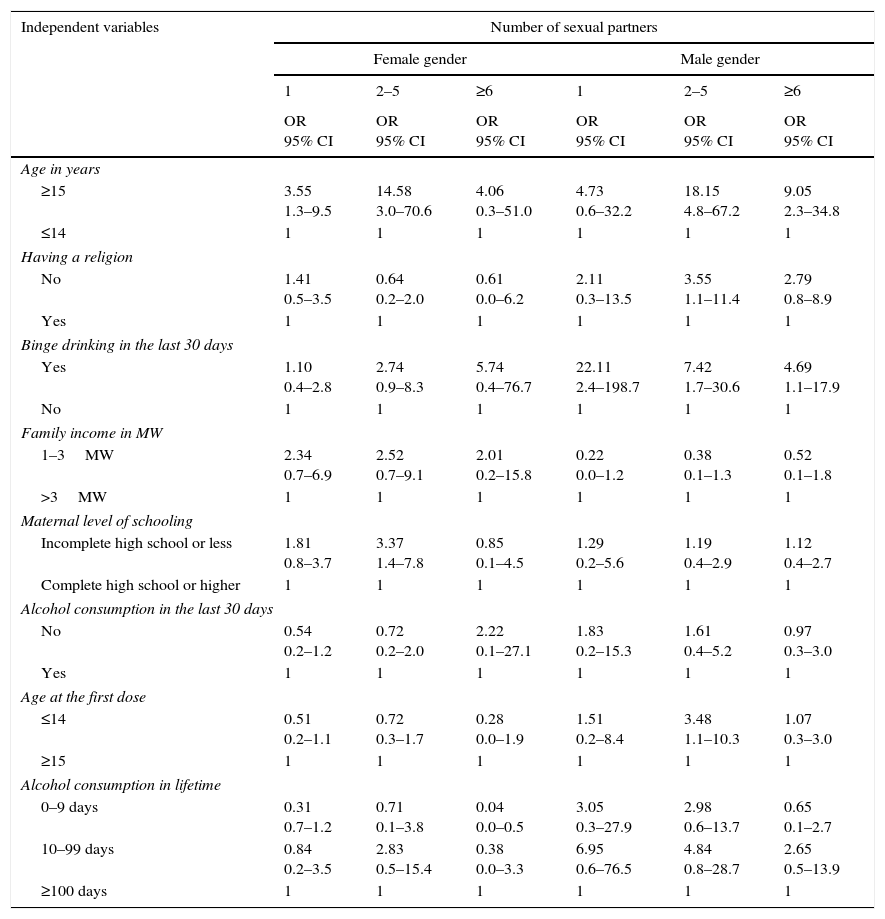

Table 4 shows the data regarding the multinomial regression, disclosing the variables that remained related to the number of lifetime sexual partners after adjusting for gender. For girls, the variables that showed a higher chance of having sexual partners were age of 15 years or older and low maternal education. Not consuming alcohol or fewer days of alcohol consumption showed a lower chance of having six or more partners. For boys, the chances of having more partners were related to age of 15 years or older, having no religion, being involved in binge drinking in the last 30 days, and having ingested the first dose of alcohol before 14 years of age.

Multinomial regression between the number of sexual partners in lifetime and independent variables adjusted for gender of adolescents and young individuals. Petrolina, PE, Brazil, 2014.

| Independent variables | Number of sexual partners | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female gender | Male gender | |||||

| 1 | 2–5 | ≥6 | 1 | 2–5 | ≥6 | |

| OR 95% CI | OR 95% CI | OR 95% CI | OR 95% CI | OR 95% CI | OR 95% CI | |

| Age in years | ||||||

| ≥15 | 3.55 1.3–9.5 | 14.58 3.0–70.6 | 4.06 0.3–51.0 | 4.73 0.6–32.2 | 18.15 4.8–67.2 | 9.05 2.3–34.8 |

| ≤14 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Having a religion | ||||||

| No | 1.41 0.5–3.5 | 0.64 0.2–2.0 | 0.61 0.0–6.2 | 2.11 0.3–13.5 | 3.55 1.1–11.4 | 2.79 0.8–8.9 |

| Yes | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Binge drinking in the last 30 days | ||||||

| Yes | 1.10 0.4–2.8 | 2.74 0.9–8.3 | 5.74 0.4–76.7 | 22.11 2.4–198.7 | 7.42 1.7–30.6 | 4.69 1.1–17.9 |

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Family income in MW | ||||||

| 1–3MW | 2.34 0.7–6.9 | 2.52 0.7–9.1 | 2.01 0.2–15.8 | 0.22 0.0–1.2 | 0.38 0.1–1.3 | 0.52 0.1–1.8 |

| >3MW | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Maternal level of schooling | ||||||

| Incomplete high school or less | 1.81 0.8–3.7 | 3.37 1.4–7.8 | 0.85 0.1–4.5 | 1.29 0.2–5.6 | 1.19 0.4–2.9 | 1.12 0.4–2.7 |

| Complete high school or higher | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Alcohol consumption in the last 30 days | ||||||

| No | 0.54 0.2–1.2 | 0.72 0.2–2.0 | 2.22 0.1–27.1 | 1.83 0.2–15.3 | 1.61 0.4–5.2 | 0.97 0.3–3.0 |

| Yes | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Age at the first dose | ||||||

| ≤14 | 0.51 0.2–1.1 | 0.72 0.3–1.7 | 0.28 0.0–1.9 | 1.51 0.2–8.4 | 3.48 1.1–10.3 | 1.07 0.3–3.0 |

| ≥15 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Alcohol consumption in lifetime | ||||||

| 0–9 days | 0.31 0.7–1.2 | 0.71 0.1–3.8 | 0.04 0.0–0.5 | 3.05 0.3–27.9 | 2.98 0.6–13.7 | 0.65 0.1–2.7 |

| 10–99 days | 0.84 0.2–3.5 | 2.83 0.5–15.4 | 0.38 0.0–3.3 | 6.95 0.6–76.5 | 4.84 0.8–28.7 | 2.65 0.5–13.9 |

| ≥100 days | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

MW, minimum wages; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Note: The total number may differ due to missing values.

Reference variable: No sexual partner.

Variables with p<0.20 remained in the regression model.

The majority of the sample reported not being sexually active, with this behavior being more prevalent in the younger age group. Several studies are in agreement with the data found in the present study, showing a similar number of adolescents who did not have sexual intercourse.1,8,18,22

Among the students who reported having an active sex life, the majority reported having one partner in the last three months; however, when asked about the number of partners in their lifetime, this value increased to two to five partners. Although higher values were already expected regarding partners during the lifetime, it should be noted that most subjects were young and had had an active sex life for a short period of time, a fact that makes these results a cause for concern. However, with increasing age, this number tends to decrease for both genders,3 being one of the probable reasons that lead adolescents to feel safer and become involved in more stable relationships.23

A high proportion of the adolescents reported not consuming alcohol at the last sexual intercourse; these data are dissimilar from those reported by other studies, which showed the consumption of large amounts of alcohol before the last intercourse.3,8 Considering these data, it is believed that the research findings can be explained as a result of the sample being from a countryside region, where the level of exposure and influences related to alcohol consumption for this group may have a different profile from those of large cities, where most research is performed.

Of the students that mentioned they had already started consuming alcohol, a uniform distribution was observed among the age groups; however, the prevalence of the age at the first dose was higher in those aged 12 years or younger, in spite of the law that prohibits the use of alcohol in this age group.16,24

Therefore, these data should be viewed with concern, as the early onset of alcohol consumption is associated with increased chances of binge drinking episodes, both in adolescence and in adulthood, as well as increased probability of potential harm to one's health.25 Previous studies have demonstrated the association between early onset of alcohol consumption and sexual risk behavior.26

The most frequent pattern of consumption in the last 30 days was that of nine doses of alcohol, i.e., most of the sample was represented by experimental/new users, whereas regarding binge drinking in the same period, a frequency of one to five episodes was observed. Binge drinking is a behavior reported by several studies that showed that, among adolescents that consume alcohol, approximately half will have at least one episode in the last two weeks.8,18

Regarding the association with the number of sexual partners, it was verified that the variables that could be included in the regression model were age, gender, religion, family income, maternal level of schooling, alcohol consumption, binge drinking in the last 30 days, age at the first dose of alcohol, and alcohol consumption in the lifetime. However, after the multinomial regression adjusted for sex, the variables that remained were age, religion, mother's education, engaging in binge drinking in the last 30 days, age of the first dose, and alcohol consumption in the lifetime.

For females, it was observed that individuals aged ≥15 years had a 3-fold higher chance of having one sexual partner and a 14-fold higher chance of having two to five partners. For male individuals at the same age group, the chance of having two to five partners was 18.15-fold higher, while the chance of having six or more partners was 9.05-fold higher. It can be inferred that although older adolescents of both genders showed greater exposure to sexual risk behavior, males were more susceptible to this behavior, which is agreement with literature data.22

Regarding religiousness, boys who mentioned not having any religion had a 3.55-fold higher chance of having two to five sexual partners. Therefore, the present study suggests that the presence of religious beliefs influences the sexual behavior of adolescents. The dissemination of standards on what would be considered correct imposed by some religions, as well as conditions, such as the prohibition of having sexual intercourse before marriage or with multiple partners, can act as attenuating factors for sexual risk behavior.1,16,17,27,28

As for the results related to maternal level of schooling, it was found that girls whose mothers had incomplete high school education or less had a 3.37-fold higher chance of having two to five sexual partners. Thus, maternal low level of schooling can be considered as an exposure factor for female adolescents to have a sexual risk behavior.

Studies have emphasized the importance of the family socioeconomic status, and both family income and parents’ education level represent indicators of risk behavior assessment for both genders.8,16

Therefore, there is an association between family income and level of schooling, as the individual within a more stable financial structure has a better chance of obtaining high quality education, with a greater possibility of knowledge about important aspects of health care.

The involvement of male individuals in binge drinking episodes in the last 30 days showed a 22.11-fold higher chance of having one sexual partner; 7.42-fold higher chance of having two to five partners; and 4.69-fold higher chance of having six or more partners. Thus, regardless of the number of partners, binge drinking is a risk factor for vulnerable sexual behavior among boys. These data have also been reported by other studies, which have indicated that both alcohol consumption and binge drinking episodes are associated with higher rates of sexual risk behavior.7,8

The combination of substance use and sexual activity seems to represent a form of stimulus for pleasure during sexual intercourse, also acting as a facilitator in the development of the sexual relationship process for both genders.18 However, this type of decision-making, in addition to being a risky behavior in itself, usually brings many possibilities and negative consequences, which are not consciously considered by these individuals with regard to their actual magnitude.29

Male adolescents who reported having ingested the first dose of alcohol at age ≤14 years had a 3.48-fold higher chance of having two to five sexual partners. In this sense, the earlier the contact with alcohol consumption, the higher the chance of having multiple sexual partners. However, the literature shows conflicting data regarding these variables, as it has been reported that the age at alcohol consumption onset has little effect on the number of sexual partners for both genders.3

Regarding alcohol use in the lifetime, girls who did not drink or were new/experimental users of alcohol had a 96% lower chance of having a higher number of sexual partners, corroborating other studies,3 which confirm that a dangerous intake of alcohol among adolescents has a negative influence on the number of sexual partners.7,8

Given the results, we can infer that the implications of this study are relevant, as it presents data related to the local scenario that can be used for comparison with other studies with adolescents from other locations; it is expected that the identified patterns can help establish health actions aimed at this population. However, certain limitations must be mentioned, such as the fact that the tool is based on self-reported answers and, therefore, it becomes necessary to consider the possibility of untruthful answers.18 Data are obtained from a specific sample in a countryside region of the state of Pernambuco and, thus, it is not possible to infer that the findings are applicable to other regions in the country or worldwide.30 Also, because this was a cross-sectional study, it is impossible to determine the causal effect of the assessed behaviors. It is also noteworthy that this study was carried out in students from public schools only and, therefore, the results are restricted to this population. Another aspect worth noting is the fact that inaccuracies may occur during data collection regarding the information on the adolescents’ parents, as children frequently do not know how to answer questions on socioeconomic data.

The authors suggest the development of panel-type studies with a longitudinal design to evaluate adolescents from different locations, assessing not only regional influences, but also between cities and countryside towns. It is also important to assess whether there are differences between the behavioral patterns of adolescents from private and public schools, as well as those from different socioeconomic levels.

Finally, one can infer that there was a high incidence of sexual risk behavior among adolescents. Age, gender, maternal education, religion, age at the first dose of alcohol, binge drinking, pattern of consumption in the last thirty days, and consumption in life were associated with the number of sexual partners.

However, boys and girls were influenced by different variables regarding the number of sexual partners. For the female gender, being aged fifteen years or older and being born to mothers that did not complete high school increased the chances of having more partners; in contrast, lower alcohol consumption during life was a protective factor for fewer sexual partners. For the male gender, being aged fifteen years or older, having no religion, start drinking before the age of fifteen, and engaging in episodes of binge drinking in the last thirty days increased the chances of having multiple sexual partners.

In summary, regardless of the number of partners, binge drinking and age of alcohol consumption onset were risk factors for sexual risk behavior.

FundingPrograma de Fortalecimento Acadêmico da Universidade de Pernambuco (PFA-UPE), Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq).

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Programa de Fortalecimento Acadêmico da Universidade de Pernambuco and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico for the grants received.

Please cite this article as: Mola R, Araújo RC, Oliveira JV, Cunha SB, Souza GF, Ribeiro LP, et al. Association between the number of sexual partners and alcohol consumption among schoolchildren. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2017;93:192–9.

Study conducted at Universidade de Pernambuco (UPE), Recife, PE, Brazil.