to evaluate the handling and risk factors for poisoning and/or digestive tract injuries associated with the use of sanitizing products at home.

Methodsinterviews were conducted in 419 households from different regions, collecting epidemiological data from residents and risk habits related to the use and storage of cleaning products.

Resultssanitizing products considered to be a health risk were found in 98% of the households where the research was conducted, and in 54% of cases, they were stored in places easily accessible to children. Lye was found in 19%, followed by illicit products in 39% of homes. In 13% of households, people produced soap, and in 12% they stored products in non-original containers. The use of illicit products and the manufacture of handmade soap were associated with lower educational level of the household owners and with the regions and socioeconomic classes with lower purchasing power.

Conclusionsrisk practices such as inadequate storage, manufacturing, and use of sanitizing products by the population evidence the need for public health policies, including educational measures, as a means of preventing accidents.

avaliar a forma de utilização e os fatores de risco para intoxicações e/ou lesões do trato digestório associados ao uso dos produtos saneantes no domicílio.

Métodosforam realizadas entrevistas em 419 domicílios de diferentes regiões, estabelecendo-se dados epidemiológicos dos moradores e hábitos de risco relacionados à utilização e armazenamento dos produtos de limpeza.

Resultadosdos domicílios onde foi realizada a pesquisa, havia produtos saneantes considerados de risco em 98%, sendo que em 54% dos casos, eles estavam armazenados em locais de fácil acesso para crianças. A soda cáustica estava disponível em 19% e os produtos “clandestinos” em 39% das moradias. Em 13% dos domicílios havia o hábito de fazer sabão e em 12% de armazenar os produtos fora da embalagem original. O uso de produtos clandestinos e a fabricação artesanal de sabão estavam associados à baixa escolaridade das donas das casas e às regiões e às classes econômicas de poder aquisitivo mais baixo.

Conclusõespráticas de risco como armazenamento, fabricação e utilização inadequados de produtos saneantes pela população estudada apontam para a necessidade de políticas de saúde pública, incluindo medidas educacionais, como forma de prevenção de acidentes.

Poisonings are responsible for high morbidity and mortality in childhood. An unsafe environment is a risk factor for injuries and poisoning in children.1 Accidental ingestion of caustic substances, which are found in many cleaning products, are among the major injuries resulting from an unsafe environment, particularly in developing countries,1,2 where these cases are often underreported. Sanitizing products are “substances or preparations intended for use on objects, fabrics, inanimate surfaces, and environments with the purpose of cleaning, disinfecting, disinfesting, sanitizing, deodorizing, and odorizing, as well as disinfection of water for human consumption, horticultural produce, and pools”, comprising: 1) cleaning products in general, and similar; 2) disinfectants, sterilizing agents, sanitizers, deodorizers, and disinfectants used in water for human consumption, horticultural produce, and pools, and 3) insecticides.3

Despite the underreporting, there have been reports, in Brazil and across the world, of cases of human poisoning and serious injuries caused by sanitizing products. Records of the American Association of Poison Control Centers (AAPCC) evidence that in 2009, there were 2,479,355 cases of human poisoning; cleaning products were responsible for 212,616 (7.4%) of all cases and for 125,394 (9.3%) of the total cases in children younger than 5 years, second only to cosmetics (13.0%) and analgesics (9.7%).4

In Brazil, data from the National Poison and Pharmacological Information System (Sistema Nacional de Informações Tóxico Farmacológicas - SINITOX) evidence that, in 2009, there were reports of 100,391 cases of human poisoning; 10,675 (10.63%) of them were caused by sanitizing products, and half (5,091) of the cases occurred with children younger than 5 years.5 Brazilian and global data confirm a higher prevalence of such accidents in children younger than 5 years and in males.2,6,7

Among the sanitizing products, those containing caustic substances must be emphasized, as they cause serious injuries to the digestive tract, which can lead to an increased risk for developing esophageal cancer.8 In addition, the ingestion of caustic products remains the leading cause of severe esophageal stenosis in children, representing the second leading cause of esophageal replacement in this age group,9 with greater difficulty regarding the dilating therapy and a higher rate of recurrence when compared to other types of esophageal stenoses.10

In pediatric patients, most cases occur by accident. The storage of cleaning products in inadequate places and the way they are used have been identified as possible risk factors for these accidents to occur.11 Most accidents occur at home12,13 and at relatives’ homes,12 where children are exposed to improperly stored toxic substances.14 Other sociodemographic conditions associated with ingestion of caustic substances have been identified, such as: low maternal educational level, large families, maternal age younger than 30 years, and working mother.12

In Brazil, there have been no studies that demonstrated how these products are used in the household or identified risk factors for poisoning and/or injuries of the digestive tract. Thus, the current study aimed to assess the use and storage of household sanitizing products by the population of the Federal District, according to its different regions, socioeconomic classes, and educational levels regarding the presence or absence of children.

MethodsThis research was conducted in the Federal District (Brazil), a region that has a population of 2,570,160 inhabitants.15 The sample was calculated to be representative of this population, based on the number of households per administrative region (AR) published by the Planning and Coordination Secretariat of the Federal District – (Secretaria de Planejamento e Coordenação do Distrito Federal – SEPLAN) and by the Planalto Central Development Company (Companhia do Desenvolvimento do Planalto Central – CODEPLAN) in 2004 as it represented, at the time of the sample calculation, the latest census of the number of households in the Federal District. In the end, the total sample consisted of 419 households distributed over 27 ARs of the Federal District.

It was assumed that the variances were constant and maximum at the strata, with a confidence level of 95% and a margin of error of 5%. These regions were grouped into I, II, and III according to the per capita income in each region. Included in Region I were the regions where the per capita income was higher than R$ 1,000; in Region II, those in which the income ranged from R$ 500 to R$ 1,000, and in Region III, those in which the income was less than R$ 500.

In each selected household, one of the residents aged 18 years or older, present at the interview, answered questions from a pre-prepared questionnaire on the use of household sanitizing products after doubts were clarified and the informed consent was signed.

The questionnaire included questions on: 1) the family sociodemographic conditions, such as number of individuals living in the household, age, and educational level of the respondent and other family members; 2) the form of storage (room and place) of cleaning products; 3) risk practices, defined as making soap at home, mixing cleaning products, disposal of packaging, reuse of the original packaging, and having lye and/or illicit products at home; 4) knowledge of the interviewee about the health risks of sanitizing products, and the habit of reading and following the directions printed on the labels.

For the assessment of household income, the Brazilian criterion of economic classification (2008) was used. This criterion divides the population into the economic classes A1, A2, B1, B2, C1, C2, D, and E. In this study, the classes A1 and A2 were grouped as A, B1 and B2 classes as B, C1 and C2 classes as C, and classes D and E as D/E.

The sanitizing products were classified according to the risk, using the criteria established by ANVISA, which classifies products as risk 1 and risk 2. Risk 1 products are those that offer less risk, have a 2 < pH < 11.5 and no corrosive characteristics, antimicrobial activity, insecticide action, are not based on viable microorganisms, and do not contain in their formulation inorganic acids such as hydrofluoric (HF), nitric (HNO3), sulfuric acid (H2SO4), or their salts. All other products are classified as risk 2.

For this study, the products considered to be health risk were manufactured products classified as risk 2 by ANVISA, including acid and alkali-based decrusting and degreasing agents, disinfectants, and bleach, as well as homemade or illicit products, for containing various concentrations of lye in their formulas. The storage of these products was considered to be safe when they were stored in a locked cupboard and/or in high place, above the eye level of an adult.

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee (REC) of the University of Brasília. Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), version 15. The level of significance was set with a confidence interval of 95%.

ResultsThe study included 419 households, from 27 ARs of the Federal District, of which 80 (19.1%) were located in Region I, 113 (27%) in Region II, and 226 (53.9%) in Region III.

The number of household members ranged from one to 11, with a mean of 3.8 people per household. There were children in 239 (57%) households. Of the respondents, 374 (89%) were females and 45 (11%) were males. There was a female homeowner in 410 (97.8%) households and a male homeowner in 308 (73.5%). The mean age of respondents was 37.3±12.5 years, with a median of 36 years. Among them, 21 (5%) were illiterate, 52 (12.4%) had not finished elementary school, 80 (19.1%) had finished elementary school, 151 (36.0%) had finished high school, and 115 (27.4%), had a college/university degree. Regarding income, 61 (14.6%) households belonged to class A, 141 (33.6%) belonged to class B, 182 (43.4%) belonged to class C, and 35 (8.4%) belonged to class D/E.

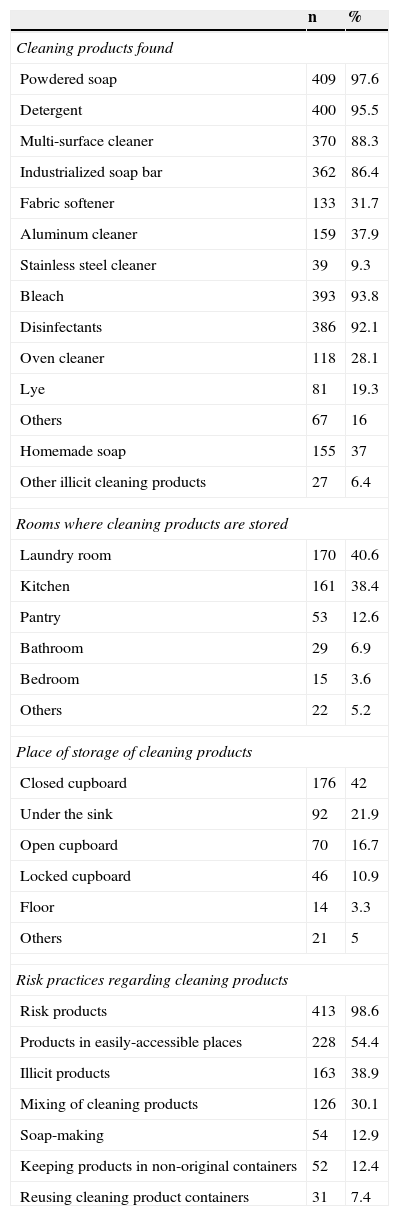

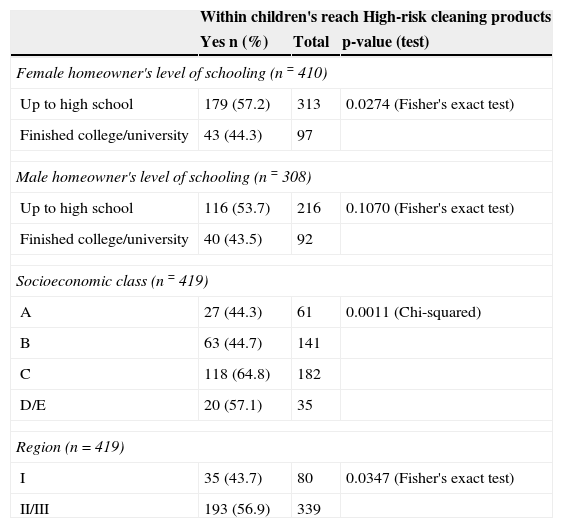

Of the 419 households assessed, 40% stored sanitizing products in the laundry room, and 38% used the kitchen, and in 228 households (54.4%) the products were stored in easily accessible places. A statistically significant association was observed between this health-risk practice and the level of education of the female homeowners, socioeconomic class, and region; it was more common in households where the highest level of education was high school, class C (low-income), and in regions II and III (lower income), respectively. Table 1 presents the data related to sanitizing products found in the households and how they were used, and Table 2 correlates the risk products stored in easily accessible places with the population's characteristics.

Use and storage of cleaning products.

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Cleaning products found | ||

| Powdered soap | 409 | 97.6 |

| Detergent | 400 | 95.5 |

| Multi-surface cleaner | 370 | 88.3 |

| Industrialized soap bar | 362 | 86.4 |

| Fabric softener | 133 | 31.7 |

| Aluminum cleaner | 159 | 37.9 |

| Stainless steel cleaner | 39 | 9.3 |

| Bleach | 393 | 93.8 |

| Disinfectants | 386 | 92.1 |

| Oven cleaner | 118 | 28.1 |

| Lye | 81 | 19.3 |

| Others | 67 | 16 |

| Homemade soap | 155 | 37 |

| Other illicit cleaning products | 27 | 6.4 |

| Rooms where cleaning products are stored | ||

| Laundry room | 170 | 40.6 |

| Kitchen | 161 | 38.4 |

| Pantry | 53 | 12.6 |

| Bathroom | 29 | 6.9 |

| Bedroom | 15 | 3.6 |

| Others | 22 | 5.2 |

| Place of storage of cleaning products | ||

| Closed cupboard | 176 | 42 |

| Under the sink | 92 | 21.9 |

| Open cupboard | 70 | 16.7 |

| Locked cupboard | 46 | 10.9 |

| Floor | 14 | 3.3 |

| Others | 21 | 5 |

| Risk practices regarding cleaning products | ||

| Risk products | 413 | 98.6 |

| Products in easily-accessible places | 228 | 54.4 |

| Illicit products | 163 | 38.9 |

| Mixing of cleaning products | 126 | 30.1 |

| Soap-making | 54 | 12.9 |

| Keeping products in non-original containers | 52 | 12.4 |

| Reusing cleaning product containers | 31 | 7.4 |

High-risk cleaning products within children's reach and association with the characteristics of the population.

| Within children's reach High-risk cleaning products | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes n (%) | Total | p-value (test) | |

| Female homeowner's level of schooling (n=410) | |||

| Up to high school | 179 (57.2) | 313 | 0.0274 (Fisher's exact test) |

| Finished college/university | 43 (44.3) | 97 | |

| Male homeowner's level of schooling (n=308) | |||

| Up to high school | 116 (53.7) | 216 | 0.1070 (Fisher's exact test) |

| Finished college/university | 40 (43.5) | 92 | |

| Socioeconomic class (n=419) | |||

| A | 27 (44.3) | 61 | 0.0011 (Chi-squared) |

| B | 63 (44.7) | 141 | |

| C | 118 (64.8) | 182 | |

| D/E | 20 (57.1) | 35 | |

| Region (n=419) | |||

| I | 35 (43.7) | 80 | 0.0347 (Fisher's exact test) |

| II/III | 193 (56.9) | 339 | |

It was observed that lye was used in 81 (19.3%) of the 419 households, and it was purchased in bulk by 22 (27.2%) of them. Regarding storage, in 15 households (22.7%) lye was not stored at home, and in 26 (32.1%) households, it was stored in easily accessible places.

Homemade products, which may also have lye in their composition, were present in almost 40% of the households visited.

When comparing the practices that may be associated with a higher risk of accidents with the presence of children in the 239 households where there were children, it was observed that in 117 households (48.9%), sanitizing products were kept in easily accessible places (p=0.01); 40 households (16.7%) had lye (p=0.13) and 72 (30.1%) had illicit products (p=0.46); and 28 households (11.7%) produced soap at home (p=0.46).

Regarding disposal of containers, in 350 (83.5%) households, empty containers were thrown in the trash, in 65 (15.5%) they were taken to be recycled, and in four (0.9%) they were disposed in a different way.

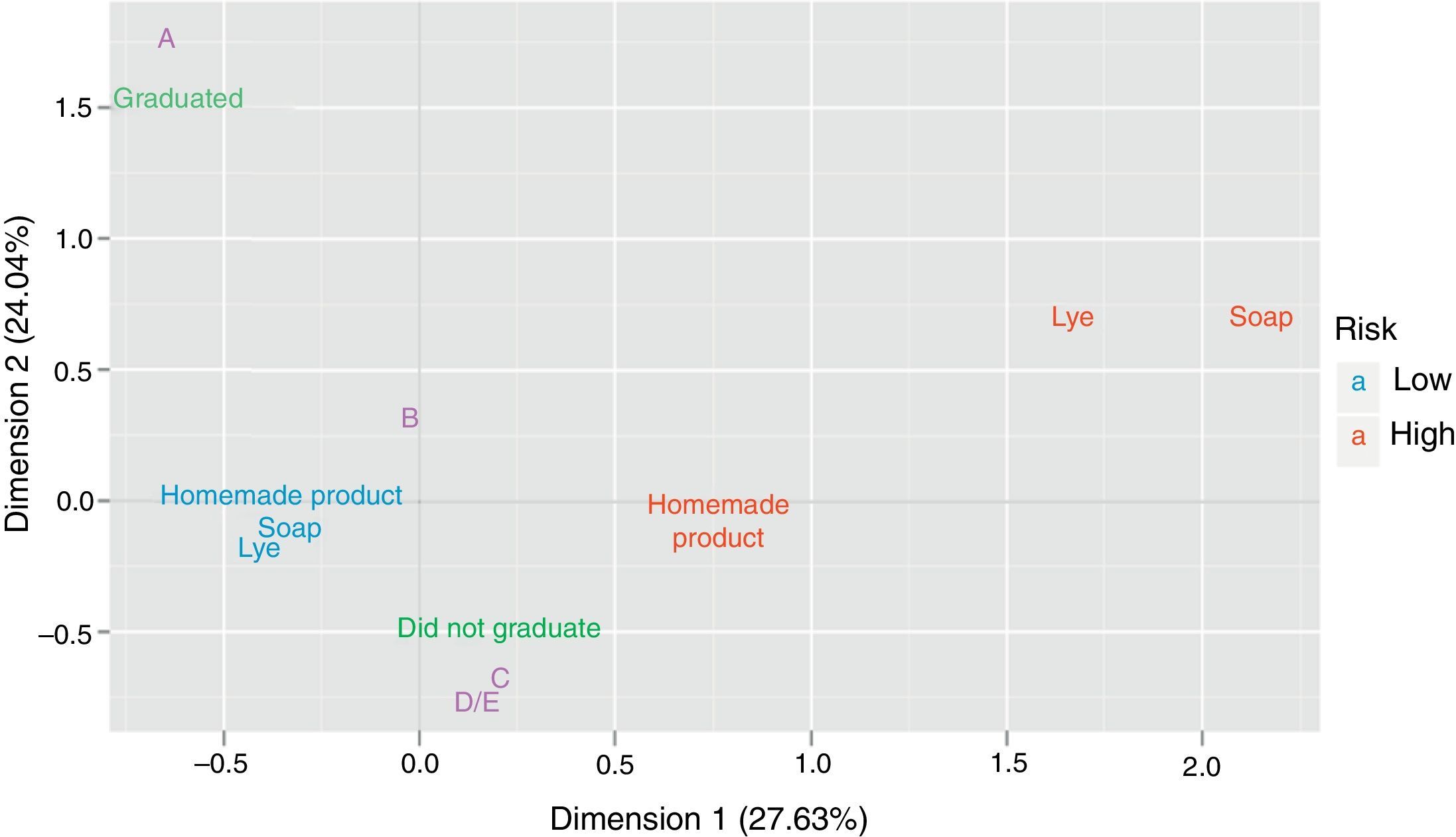

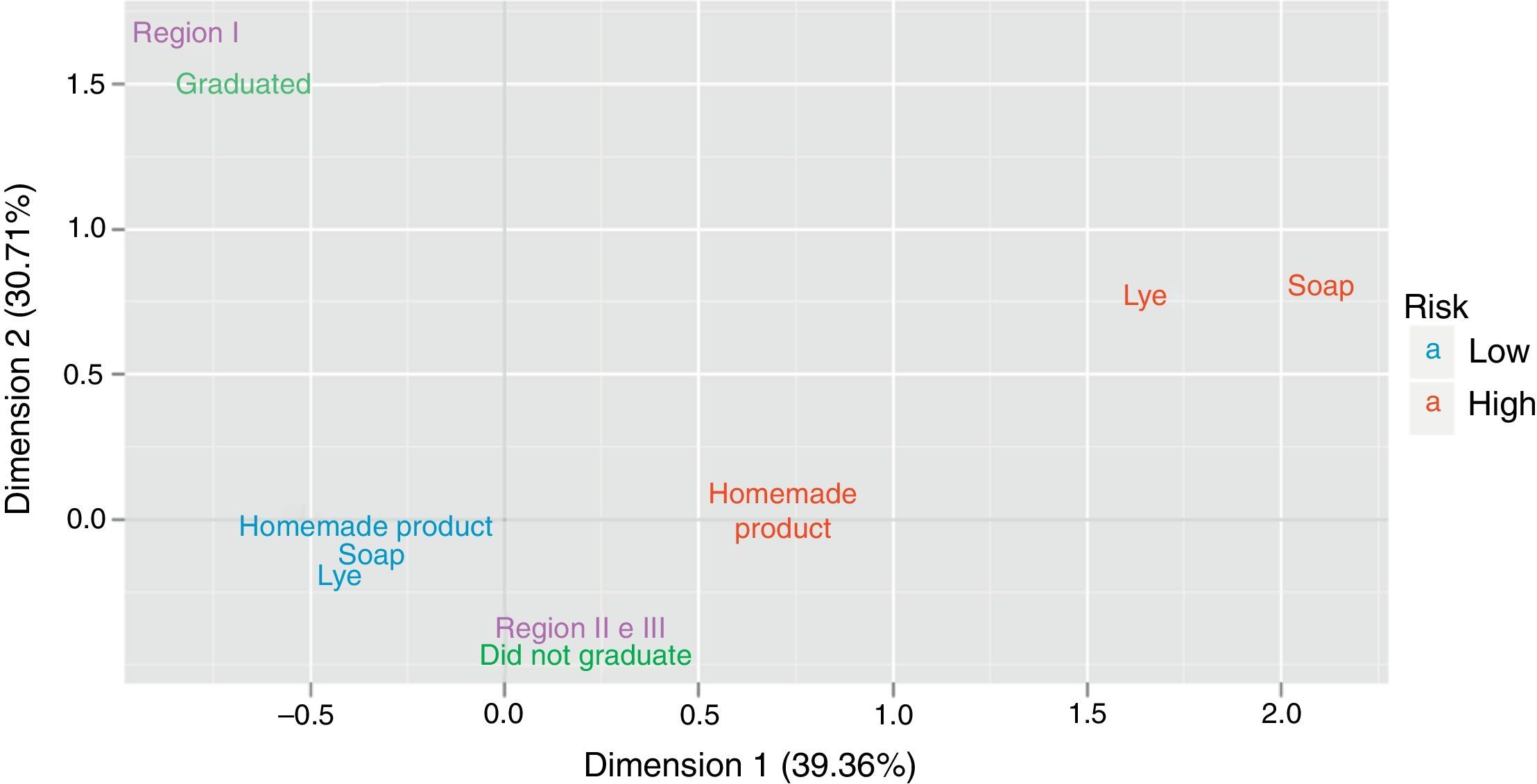

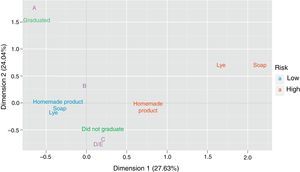

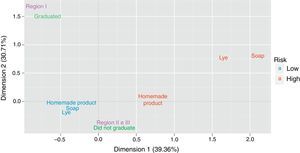

Through analysis of correspondence using charts (Figs. 1 and 2), it is suggested that factors such as lower educational level (up to high school); belonging to classes C and D/E, and living in regions II and III (lower income), were associated with a greater chance of using illicit products, making soap at home, and using lye at home.

Regarding the knowledge related to home use, of the 419 respondents asked about the risks of sanitizing products, 316 (75.4%) answered that these products posed a risk to health, 58 (13.8%) answered that they did not offer any risk, and 45 (10.7%) said they did not know. Of the 419 respondents, 231 (55%) stated that they read the labels of these products and 209 (49.9%) claimed to follow the instructions written on the labels.

DiscussionThe sociodemographic data of the study population, when analyzed, are suggestive of a representative sample of the different social classes, whose schooling levels were within the estimated values for the population of the Federal District, according to the census performed by the IBGE in 2010.15

In this study, the products that were most often found were: powdered soap and soap bars, detergents, bleach, and disinfectants, present in almost all households in which the survey was performed. In the study by Nickmilder et al, disinfectants were the most often used products.16 In the study by Sawalha, bleach was the one most frequently found (96.7%), followed by acid products (86.4%).11

It was observed that the laundry room was the most common place to store these products, followed by the kitchen, different from study by Beirens et al., conducted in the Netherlands, in which the kitchen (90.9%) was the main storage room.17 In the present study, it is noteworthy that over half of the products were stored in low or intermediate levels, including the floor and under the sink or laundry tub. According to Schwartsman, one of the main factors leading to poisoning in children appears to be the easy access to toxic substances,18 often stored in cupboards or under sinks (low areas). Therefore, it is observed that half of the studied population is exposed to a greater chance of accidents.

It is worth noting the high rate of homemade products present in households, as well as lye, often bought in bulk (a practice prohibited by law19) and stored in easily accessible places in most cases.

Common risk practices were observed in the households of the Federal District, such as mixing cleaning products, reuse of the original packaging, and storing products in non-original containers. In the study by Sawalha, which included 735 households, these products were stored in suboptimal places and were within the reach of children. It was mixed cleaning products (22%) in a smaller proportion of cases and, most frequently, reused product containers (20.5%) and stored the products out of the original containers (26.9%).11 In the study by Smolinske and Kaufman, bleach was stored in low places in 21.8% of the 357 households, and in 19% they stored sanitizing products out of the original container.20

In approximately half of the households where there were children, there were sanitizing products in easily accessible places (p=0.01). These data were similar to those from a study conducted in the city of Porto Alegre, Southern Brazil, where 309 parents of children treated at the pediatric clinic of a university hospital were interviewed, and 184 (59.5%) stored their cleaning products in potentially hazardous locations.21 The data observed in the present study is also similar to those of the Institute of Medicine of the National Academies, according to which over half of the households that had children younger than 6 years had chemicals stored in unlocked cupboards,22 and to that of the study by Beirens, in which almost all children (99%) were potentially exposed to cleaning products, which were stored in easily accessible places in half of the households.17

Interestingly, although most of the respondents considered that the sanitizing products were a health risk, there was a low incidence of reading and following the directions on labels. Moreover, these numbers may be even lower, as a study performed in Pennsylvania demonstrated that of the 76% of respondents who claimed to have read the labels, less than 5% had actually done so.23

Based on the data from this study, it appears that a large part of the population of the Federal District, particularly in the pediatric age group, is exposed to a high risk of accidents at home, caused by the inadequate storage of sanitizing products, including those that offer greater health risk. Thus, it is important and urgent to implement public health policies, including educational measures, to clarify how sanitizing products should be correctly stored, as well as the risks and consequences of their inappropriate use, especially in low-income areas and where educational levels are lower, in order to prevent accidents in childhood.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Silva AA, Passos RS, Simeoni LA, Neves FA, Carvalho E. Use of sanitizing products: safety practices and risk situations. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2014;90:149–54.