To assess spontaneous reports of suspected adverse drug reactions in children aged 0–12 years from the Brazilian Health Regulatory Agency between 2008 and 2013.

MethodsA cross-sectional study on suspected adverse drug reactions reports related to medicines and health products in children was carried out for a six-year period (2008–2013). Year of report, origin of report by Brazilian state, gender, age, suspected drug, adverse reaction description and seriousness were included in the analysis. The data obtained was compared to the number of pediatric beds in health services and to global data from the VigiBase (World Health Organization).

ResultsA total of 3330 adverse drug reactions were reported in children in Brazil in the investigated period (54% were in boys). About 28% of suspected adverse drug reactions reports involved 0 to 1-year-old children. Almost 40% of reports came from the Southeast region. Approximately 60% were classified as serious events. There was death in 75 cases. Nearly 30% of deaths involved off-label use; 3875 medicines (465 active substances) were considered suspected drugs. Anti-infective (vancomycin, ceftriaxone, oxacillin, and amphotericin), nervous system (metamizole) and alimentary tract and metabolism medicines were more frequent in reports.

ConclusionsThe distribution of suspected adverse drug reactions reports by sex and age group corresponded to the profile of children hospitalized in Brazil. Data about seriousness and medicines reported may be useful to encourage regulatory actions and improve the safe use of medicines in children.

Analisar relatos espontâneos de suspeitas de Reação Adversa a Medicamento (RAM) em crianças de 0 a 12 anos notificadas pela Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária entre 2008 e 2013.

MétodosUm estudo transversal a partir de notificações de suspeitas de RAM relacionadas a medicamentos e produtos para a saúde em crianças foi realizado por um período de seis anos (2008-2013). O ano da notificação, a origem do relato por estado brasileiro, sexo, idade, o medicamento suspeito, a descrição da reação adversa e a gravidade foram incluídos na análise, bem como o número de leitos nos serviços de saúde e dados global da VigiBase.

ResultadosUm total de 3330 reações adversas foram relatadas em crianças no Brasil no período investigado (54% em meninos). Cerca de 28% dos relatos de suspeitas de RAM envolveram crianças de 0 a 1 ano de idade. Quase 40% dos relatos vieram da região Sudeste. Aproximadamente 60% foram classificados como eventos graves. Houve ocorrência de morte em 75 casos. Quase 30% das mortes envolveram o uso off-label dos medicamentos. Um total de 3875 medicamentos (465 substâncias ativas) foram considerados fármacos suspeitos. Medicamentos anti-infecciosos (vancomicina, ceftriaxona, oxacilina e anfotericina), com ação no sistema nervoso (dipirona) e no trato digestivo foram os mais frequentemente notificados.

ConclusõesAs notificações de suspeitas de RAM por sexo e faixa etária corresponderam ao perfil de crianças hospitalizadas no Brasil. Os dados sobre gravidade e medicamentos relatados podem ser úteis para encorajar ações reguladoras e melhorar o uso seguro de medicamentos em crianças.

Children are especially vulnerable to adverse drug reactions (ADRs) and incidence rates range from 0.6% to 16.8% of children exposed to a drug during a hospital stay.1 These susceptibilities are explained in part by physiological changes during growth, influencing drug bioavailability and disposition. Lack of information from clinical trials increases the uncertainties about the benefit–risk profile of commonly used medicines in pediatrics.2,3

ADRs are defined as a response to a drug that is noxious and unintended, and which occurs at doses normally used in humans for the prophylaxis, diagnosis, and therapy of disease, or for the modification of a physiological function.4 Currently, several methods and approaches for detection of suspected ADR and for receiving and analyzing reports of safety alerts are used. Spontaneous reports of suspected ADRs – the main activity of National Pharmacovigilance Centers – are considered an accessible, cheap strategy that is especially useful for the discovery of rare and previously unreported reactions.4 On the other hand, underreporting, low quality of reports and difficulty in estimating frequencies and suspected ADR rates are some of its limitations.5

Star et al. found a higher proportion of reports involving children originating from Latin America, compared to Europe, North America and Oceania, based on the WHO global ICSR database, VigiBase.2 In Brazil – the biggest country in Latin America, with a multiethnic population estimated at almost 200 million inhabitants – data reporting and collection has been planned under health surveillance for four decades. However, the Brazilian Health Regulatory Agency (Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária, or Anvisa) was only was founded by law in 1999. Brazil was admitted as the 62nd International Program Member, and its National Center for Drug Monitoring (Centro Nacional de Monitorização de Medicamentos) was established in 2001, when the national census reported over 170 million inhabitants. The Brazilian online system for ADR reporting (Sistema Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária, Notivisa) was created on a web platform in 2006.6,7 Notivisa receives reports of suspected ADRs from health professionals, industry, and health facilities. Most reports come from risk managers in the Sentinel Network that has been supported by hospitals since 2004 across the whole country, though distribution of network sites is unequal.8,9

In comparison with the United States and with European health regulatory agencies Brazil does not have any specific regulation or governmental initiatives to improve clinical research in children. The lack of governmental initiatives in pediatrics creates a scenario that is conducive to irrational drug use like unlicensed and off-label uses followed by an increased risk of children hospitalization.10,11

Considering these aspects, as well as the necessity to know the profile of suspected ADRs among children in Brazil – where medication use will be specific to the public health problems in this tropical, socially diverse country –, this study aims to describe and assess spontaneous reports of suspected adverse drug reactions (ADRs) in children aged 0–12 years from Notivisa.

MethodsThe authors carried out a cross-sectional study on suspected ADR reports related to medicines and health products (excluding vaccines) made by health professionals, the pharmaceutical industry and health services between 2008 and 2013 in Brazil. Anvisa supplied data from Notivisa website reports in an unlinked, anonymized format as a Microsoft Excel® file.

Data on suspected ADRs in children (0–12 years old) was identified and included in two ways: (i) combination of age information variables on the date of adverse event occurrence or (ii) calculation of the difference between the date of commencement of the suspected ADR and the patient's birth date. There were no linkage processes with other databases. Records in which the date of birth was not informed were excluded from the study.

A report of suspected ADR was considered as being the analytical unit and study ordered variable. Variables related to patient (gender and age), suspected drug (name, dose administered, route, frequency), suspected ADR (description, duration and seriousness) and origin of report (year, city and state) were investigated in this study.

Drugs were encoded using the Anatomic Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification system, and their frequency was analyzed regarding therapeutic group and subgroup. Off-label drug information in children was verified with the Anvisa electronic package insert list and complemented by the Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC) and patient information leaflet (PIL) on the electronic Medicines Compendium (eMC) and Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). Both sources contain up-to-date, easily accessible information about medicines licensed for use in the United Kingdom and were considered because the UK has specific information policies about medicines for children.

The suspected ADRs were classified by WHO Adverse Reaction Terminology (WHO-ART). All suspected ADRs were classified in (i) serious: death, life-threatening, prolonged hospitalization, congenital abnormalities, persistent or significant disability, medically important events or (ii) not serious.12

Data from the Brazilian pediatric population, morbidity profile and number of pediatric beds in health services in states were collected from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística, or IBGE), and the Brazilian Health System Informatics Department (Departamento de Informática do SUS – DATASUS)13 was considered to compare suspected ADR reports and relative frequency.

Global data was sourced from the database VigiAccess to gain public access to VigiBase, the World Health Organization (WHO)’s global database for suspected ADRs, maintained by the Uppsala Monitoring Center (UMC).14 The number of global reports of suspected ADRs in 0 to 11-year-old children between 2008 and 2013 was estimated from the total reported during the period multiplied by the percentage of suspected ADRs in that age group informed in the VigiAccess.

This study was approved by a Brazilian Research Ethics Committee (registry number 931.400).

ResultsThere were 41,657,159 children aged 0–12 years in Brazil according to national estimates in 2013. The suspected ADRs in this population (n=3330) represented 10.4% of total suspected ADRs from Notivisa between 2008 and 2013. About 4% of reports did not have the date of birth of the patient and thus were excluded.

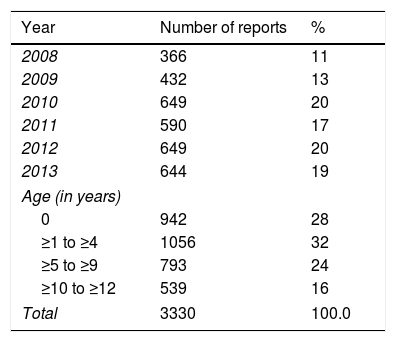

The annual number of reports in children aged 0–12 years ranged from 365 to 644 in Brazil (Table 1). There were suspected ADR reports from all five Brazilian regions. Almost 40% of the reporting was carried out in the Southeast region. The Midwest had the worse results (Supplementary Table 1). Two Brazilian states (Roraima and Amapá) have not reported events in children. Roraima is the state with the largest proportion of children in Brazil (45%). São Paulo (n=908; 27.3%), Pará (n=353; 10.6%), Santa Catarina (n=329; 9.9%), Rio Grande do Sul (n=318; 9.5%), Ceará (n=305; 9.1%) and Minas Gerais (n=217; 6.5%) were the states with the largest number of reports.

Distribution of suspect ADR reports in children (0–12 years old) by year and age range (Brazil, 2008–2013).

| Year | Number of reports | % |

|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 366 | 11 |

| 2009 | 432 | 13 |

| 2010 | 649 | 20 |

| 2011 | 590 | 17 |

| 2012 | 649 | 20 |

| 2013 | 644 | 19 |

| Age (in years) | ||

| 0 | 942 | 28 |

| ≥1 to ≥4 | 1056 | 32 |

| ≥5 to ≥9 | 793 | 24 |

| ≥10 to ≥12 | 539 | 16 |

| Total | 3330 | 100.0 |

ADR, adverse drug reaction.

About 28% of suspected ADR reports involved 0 to 1-year-old children. Mean and median ages were 4 and 3 years old, respectively (Table 1). The number of reports by gender was 1788 (53.7%) in boys; in 73 (2.2%) of the reports that variable was missing. Distribution of suspected ADR reports by sex and age group corresponded to the profile of children hospitalized in Brazil.13

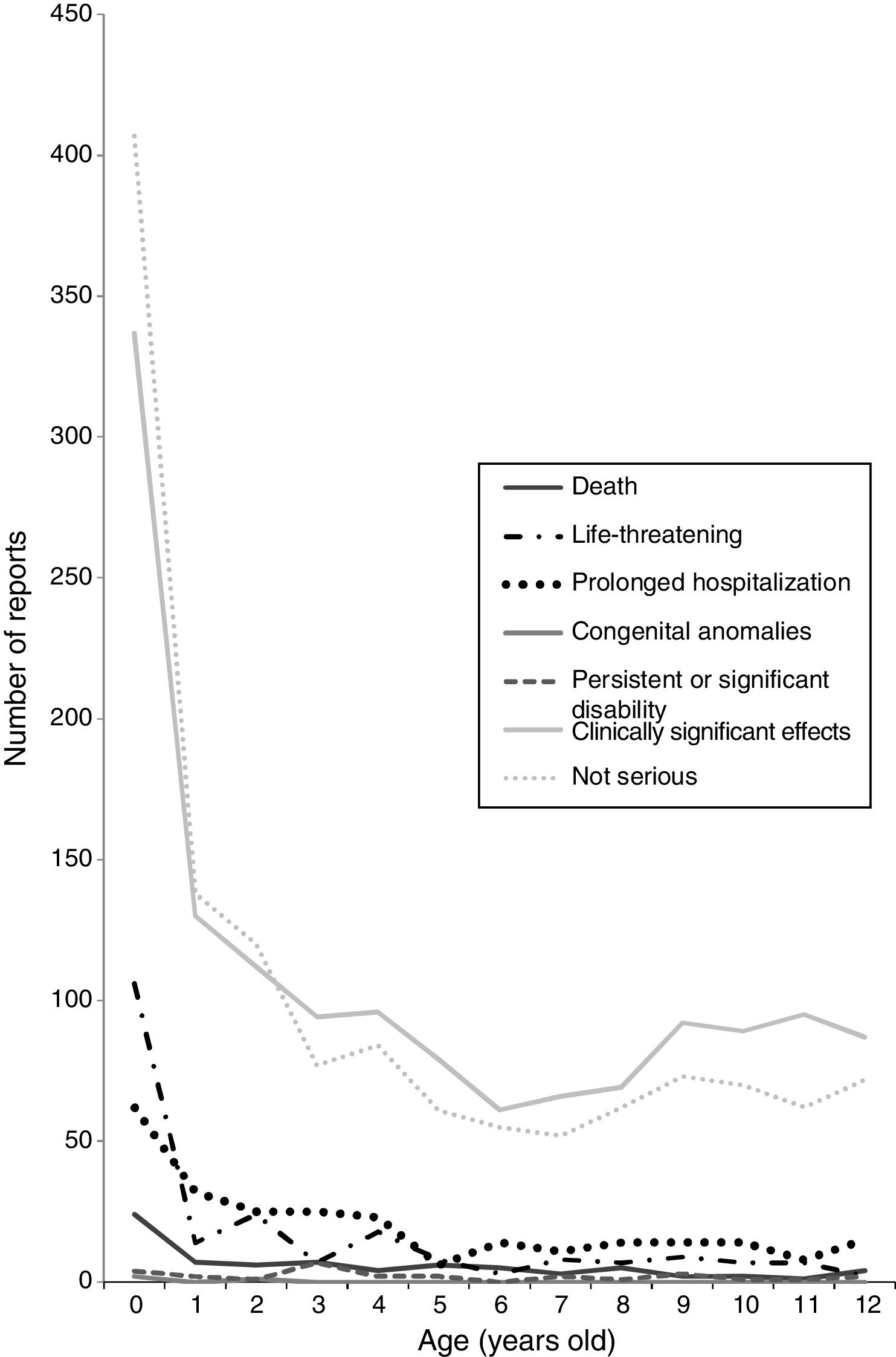

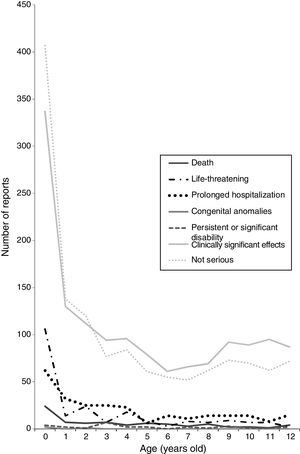

Approximately 60% of reports were classified as serious suspected ADRs (Fig. 1). Death, life-threatening, prolonged hospitalization, congenital abnormalities and persistent or significant disability corresponded to 18% of the reports. There were death and life-threatening events in 75 (2.3%) and 213 (6.4%) cases respectively. The deaths were related to “other” alimentary tract and metabolism products such as enzymes, antibacterial drugs for systemic use and antineoplastic agents. Twenty-three death cases (30%) involved off-label use. Younger children tend to present more serious suspected ADRs (Supplementary Fig. 1).

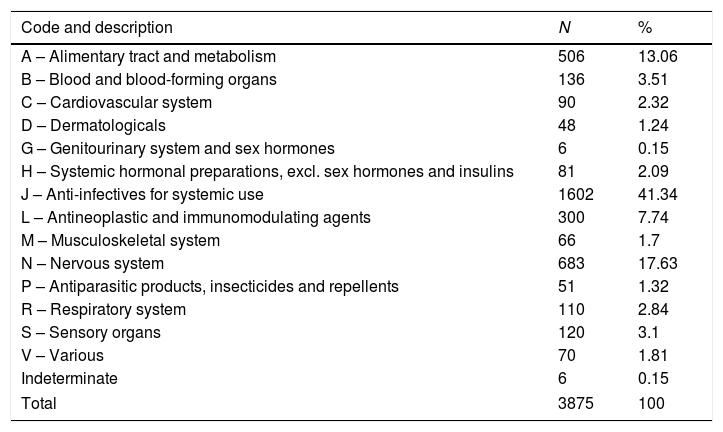

A total of 3875 medicines (465 active substances) were identified in 3330 reports (mean: 1.2 suspected drugs per report; range from 1 to 14). Anti-infectives (41%), nervous system (17%) and alimentary tract and metabolism (13%) medicines were more frequent in the reports (Table 2).

Drug groups (ATC) implicated in suspect ADRs in children aged 0–12 years (Brazil, 2008–2013).

| Code and description | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| A – Alimentary tract and metabolism | 506 | 13.06 |

| B – Blood and blood-forming organs | 136 | 3.51 |

| C – Cardiovascular system | 90 | 2.32 |

| D – Dermatologicals | 48 | 1.24 |

| G – Genitourinary system and sex hormones | 6 | 0.15 |

| H – Systemic hormonal preparations, excl. sex hormones and insulins | 81 | 2.09 |

| J – Anti-infectives for systemic use | 1602 | 41.34 |

| L – Antineoplastic and immunomodulating agents | 300 | 7.74 |

| M – Musculoskeletal system | 66 | 1.7 |

| N – Nervous system | 683 | 17.63 |

| P – Antiparasitic products, insecticides and repellents | 51 | 1.32 |

| R – Respiratory system | 110 | 2.84 |

| S – Sensory organs | 120 | 3.1 |

| V – Various | 70 | 1.81 |

| Indeterminate | 6 | 0.15 |

| Total | 3875 | 100 |

ADR, adverse drug reaction; ATC, Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Code.

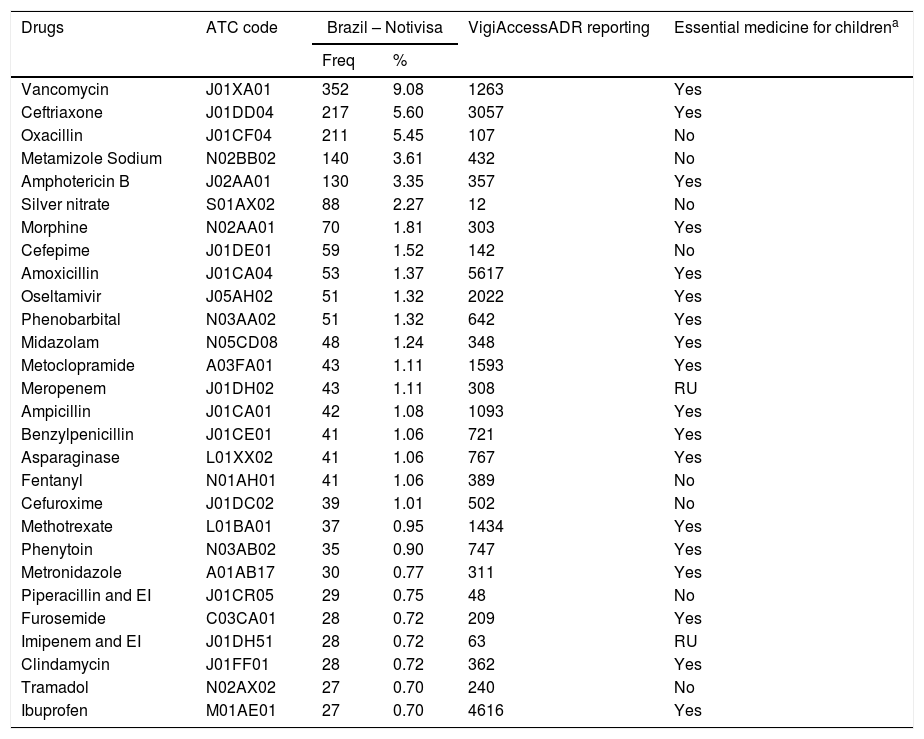

Vancomycin was the medicine most frequently (352 reports) involved in suspected ADRs among Brazilian children (as well as serious events), followed by ceftriaxone (217), oxacillin (211), metamizole (140) and amphotericin (130). The most frequently reported active substances are shown by 5th-level ATC codes in Table 3. According to VigiBase, there were over 13,000 reports involving ibuprofen, amoxicillin and ceftriaxone use in children around the world between 2008 and 2013 (Table 3). Those medicines were suspected in 5155 reactions (average 1.56 reactions per report), and reactions were classified in 662 different codes. Dermatological reactions were the most frequently reported. The most frequently reported events (frequency above 1%) are shown in Supplementary Table 2.

Drugs more implicated in suspect ADRs reported in children (Brazil, 2008–2013).

| Drugs | ATC code | Brazil – Notivisa | VigiAccessADR reporting | Essential medicine for childrena | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freq | % | ||||

| Vancomycin | J01XA01 | 352 | 9.08 | 1263 | Yes |

| Ceftriaxone | J01DD04 | 217 | 5.60 | 3057 | Yes |

| Oxacillin | J01CF04 | 211 | 5.45 | 107 | No |

| Metamizole Sodium | N02BB02 | 140 | 3.61 | 432 | No |

| Amphotericin B | J02AA01 | 130 | 3.35 | 357 | Yes |

| Silver nitrate | S01AX02 | 88 | 2.27 | 12 | No |

| Morphine | N02AA01 | 70 | 1.81 | 303 | Yes |

| Cefepime | J01DE01 | 59 | 1.52 | 142 | No |

| Amoxicillin | J01CA04 | 53 | 1.37 | 5617 | Yes |

| Oseltamivir | J05AH02 | 51 | 1.32 | 2022 | Yes |

| Phenobarbital | N03AA02 | 51 | 1.32 | 642 | Yes |

| Midazolam | N05CD08 | 48 | 1.24 | 348 | Yes |

| Metoclopramide | A03FA01 | 43 | 1.11 | 1593 | Yes |

| Meropenem | J01DH02 | 43 | 1.11 | 308 | RU |

| Ampicillin | J01CA01 | 42 | 1.08 | 1093 | Yes |

| Benzylpenicillin | J01CE01 | 41 | 1.06 | 721 | Yes |

| Asparaginase | L01XX02 | 41 | 1.06 | 767 | Yes |

| Fentanyl | N01AH01 | 41 | 1.06 | 389 | No |

| Cefuroxime | J01DC02 | 39 | 1.01 | 502 | No |

| Methotrexate | L01BA01 | 37 | 0.95 | 1434 | Yes |

| Phenytoin | N03AB02 | 35 | 0.90 | 747 | Yes |

| Metronidazole | A01AB17 | 30 | 0.77 | 311 | Yes |

| Piperacillin and EI | J01CR05 | 29 | 0.75 | 48 | No |

| Furosemide | C03CA01 | 28 | 0.72 | 209 | Yes |

| Imipenem and EI | J01DH51 | 28 | 0.72 | 63 | RU |

| Clindamycin | J01FF01 | 28 | 0.72 | 362 | Yes |

| Tramadol | N02AX02 | 27 | 0.70 | 240 | No |

| Ibuprofen | M01AE01 | 27 | 0.70 | 4616 | Yes |

ADR, adverse drug reaction; ATC, Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Code; RU, restrict use; EI, enzyme inhibitor.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first work on suspected ADRs in children from the Brazilian pharmacovigilance system.

The increase in patients with suspected ADRs was observed both in children and in adults and it can be related to Anvisa actions and the consolidation of the Sentinel Network (Rede Sentinela) in Brazil.6 Regulations on pharmacovigilance for drug manufacturers and post-marketing drug safety surveillance were published in 2009. Following that, the Patient Safety National Program (Programa Nacional de Segurança do Paciente, PNSP)’s actions were established by law. As of 2010, however, the number of patients did not vary greatly among children, though continuing to grow among adults, which may be due to stagnation in the number of pediatric hospitals in the sentinel network. In its initial phase, the Sentinel Network was a project focused on training professionals from 96 participating hospitals and it aimed to promote the management of hospital health risks. There were 195 hospitals registered in the network in 2013.15

According to Anvisa, nearly 80% of suspected ADR for all ages in Brazil were reported by hospitals.15 Our findings corroborate that statement and also show a low rate of reporting from the Midwestern region, which may indicate underreporting. However, the variation between regions suggests that it is possible to improve suspected ADR reporting.

Among the 215 hospitals registered in the Sentinel Network, the highest number – 60 hospitals (25%) – is located in the state of São Paulo. The states of Minas Gerais and Rio de Janeiro (Southeast) had the same number of health facilities (22) as Paraná and Rio Grande do Sul (South) (12). Santa Catarina (South), Ceará (Northeast) and Pará (North) had 19, 9 and 4 registered hospitals, respectively.15 Pioneering initiatives to implement pharmacovigilance projects occurred in Ceará, Paraná and São Paulo in the 1990s.8

Differences between sexes also can be related to the profile of hospitalization among Brazilian children during the study period, which is more frequent in male patients (55%).16 Moore et al. evaluated the occurrence of ADRs in children under 2 years of age and found that boys accounted for 57% of reports. ADRs occurred with a higher incidence at younger ages.17

Age appears to influence the incidence of serious reports. Studies on drug safety are less common among younger children, despite the specific pharmacokinetics that are found in children aged 0–3 years that may hinder the monitoring and management of adverse reactions.18

Deaths related to off-label use (30% of deaths associated with a suspected ADR) are an important finding. This percentage was not expected, considering a certain reluctance to report deaths caused by the suspected use of off-label or unlicensed prescribing.19 Nevertheless, the major potential harm associated with unlicensed and off-label drug uses is the increase in adverse drug reactions.10

The main classes of suspected drugs – ATC groups J, N and A – are widely administered to hospitalized children in Brazil as well as in European countries.20,21 Diarrhea, lower respiratory and other infections in children and adolescents are more common in Brazil than in developed countries.16

A systematic review about suspected ADRs in children found that anti-infective and anti-epileptic drugs were the most commonly reported drug classes in 52 studies.1 Among the drugs listed in Table 3, 5 (metamizole sodium, oxacillin, ceftriaxone, furosemide and phenobarbital) are the most prescribed in pediatric wards at a maternal and children's hospital in Brasília.22 Midazolam, metamizole sodium, fentanyl, cefepime, vancomycin, diazepam, and furosemide were presented as the most frequently used drugs in the intensive care unit of the Hospital das Clínicas de Porto Alegre.23 Metamizole sodium (dipyrone) use was also indicated in recent studies conducted in the states of São Paulo and Minas Gerais,24,25 but this drug was banned in the United States, United Kingdom, Sweden and India due to the risk of agranulocytosis.26 Still, ibuprofen is a commonly used drug in Europe.21

Despite the similarities between classes, drug profiles involved in suspected ADRs found in this study were different from the data from other pediatric studies and VigiAccess. A few drugs (amoxicillin, ampicillin, methotrexate, furosemide and ibuprofen) were commonly reported by Anvisa (Brazil) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Adverse Event Reporting System (AERS).27

Vancomycin and oxacillin are related to a greater frequency of suspected ADRs in hospitalized children in Brazil and are widely used in high-complexity care.28 Cloxacillin is the isoxazolyl penicillin recommended for children, but it is not registered in Brazil.

Shalviri et al.29 analyzed the records of suspected ADRs in adults and children in Iran over a period of ten years (1999–2008). These authors concluded that ceftriaxone was the most common drug in notifications (5.8%), accounting for 49 deaths. The concomitant use of ceftriaxone and calcium-containing solutions appears to result in severe reactions.29 Bradley et al. described 9 serious suspected ADR cases related to the association between ceftriaxone and calcium in children, especially neonates.30

Skin disorders and vomiting were the main suspected ADRs reported in this study, in agreement with similar studies and systematic reviews of ADRs in children.1,27,28,31 Skin also was the most affected organ according to Vigibase reports in children, and authors suggest that it may relate to physiological differences increasing the predisposition for skin reactions.2

Although all events were collected from Anvisa, detailed information is incomplete in some cases, making a causality analysis difficult. Suspected ADR underreporting is estimated in the literature as likely to be more than 90%.32 This is an important problem, as it makes it impossible to know the real frequency.31 Other limitations related to secondary databases for this study included coding errors, inability to link to parental data and birth weight, current height and weight.33

A heterogeneous distribution of hospitals by region (70% in the Southern and Southeastern regions) and the focus on cases of greater complexity in those services may have introduced some bias, as it is not possible to know common events in the general population. However, it is clear that Brazilian hospital services generate a specific pattern of suspected ADRs. The general population is also likely to have a Brazil-specific pattern of ADRs, and this deserves future work.

Reports involving drugs like oxacillin, ceftriaxone and metamizole indicate the relevance of new studies approaching pediatric pharmacoepidemiology and market regulation differences. There are some distinct features of practice in Brazil – as, for example, cloxacillin unavailability and metamizole over-the-counter availability – which implies the need for country-specific pharmacovigilance and careful pediatric drug monitoring. The health of Brazilian children is not adequately protected by legislative requirements compared to the US and European countries. Finally, studies about causality and avoidability of serious suspected ADRs also appear to be extremely important, and they need to be done in Brazil.

This investigation showed that the overall distribution of suspected ADR reports by sex and age group corresponded to the profile of children hospitalized in Brazil in the same period. Similarly, the main classes of suspect drugs – anti-infective (vancomycin, ceftriaxone, oxacillin and amphotericin), nervous system (metamizole) and alimentary tract and metabolism medicines – are widely administered to hospitalized children in Brazil and in European countries.

Our findings suggest that suspected ADR reporting can be improved, especially in the Midwest. Considering the lack of specific regulation for pediatric medicines in Brazil, we suggest that the country develop its own approach to pharmacovigilance practice and policy.

FundingBrazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico – CNPq).

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The authors would like to thank the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development for research funding and Anvisa for its support through data access.

Please cite this article as: Lima EC, Matos GC, Vieira JM, Gonçalves IC, Cabral LM, Turner MA. Suspected adverse drug reactions reported for Brazilian children: cross-sectional study. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2019;95:682–8.

Study conducted at Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Faculdade de Farmácia, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil.