Childhood obesity has become a priority health concern worldwide. Socioeconomic status is one of its main determinants. This study aimed to assess the socioeconomic inequality of obesity in children and adolescents at national and provincial levels in Iran.

MethodsThis multicenter cross-sectional study was conducted in 2011–2012, as part of a national school-based surveillance program performed in 40,000 students, aged 6–18-years, from urban and rural areas of 30 provinces of Iran. Using principle component analysis, the socioeconomic status of participants was categorized to quintiles. Socioeconomic status inequality in excess weight was estimated by calculating the prevalence of excess weight (i.e., overweight, generalized obesity, and abdominal obesity) across the socioeconomic status quintiles, the concentration index, and slope index of inequality. The determinants of this inequality were determined by the Oaxaca Blinder decomposition.

ResultsOverall, 36,529 students completed the study (response rate: 91.32%); 50.79% of whom were boys and 74.23% were urban inhabitants. The mean (standard deviation) age was 12.14 (3.36) years. The prevalence of overweight, generalized obesity, and abdominal obesity was 11.51%, 8.35%, and 17.87%, respectively. The SII for overweight, obesity and abdominal obesity was −0.1, −0.1 and −0.15, respectively. Concentration index for overweight, generalized obesity, and abdominal obesity was positive, which indicate inequality in favor of low socioeconomic status groups. Area of residence, family history of obesity, and age were the most contributing factors to the inequality of obesity prevalence observed between the highest and lowest socioeconomic status groups.

ConclusionThis study provides considerable information on the high prevalence of excess weight in families with higher socioeconomic status at national and provincial levels. These findings can be used for international comparisons and for healthcare policies, improving their programming by considering differences at provincial levels.

A obesidade infantil se tornou uma preocupação de saúde prioritária em todo o mundo. A situação socioeconômica (SSE) é um de seus principais determinantes. Este estudo tem como objetivo avaliar a desigualdade socioeconômica com relação à obesidade entre crianças e adolescentes em nível nacional e subnacional no Irã.

MétodosEste estudo transversal multicêntrico foi conduzido em 2011-2012 como parte de um programa nacional de vigilância escolar realizado com 40000 alunos, com idade entre 6-18 anos, de áreas urbanas e rurais de 30 províncias do Irã. Utilizando a análise de componentes principais, a SSE dos participantes foi categorizada em quintis. A desigualdade da SSE no excesso de peso foi estimada pelo cálculo da prevalência de excesso de peso (ou seja, sobrepeso, obesidade geral e obesidade abdominal) em todos os quintis da SSE, o índice de concentração (C) e o slope index of inequality (SII). Os determinantes dessa desigualdade foram determinados pela decomposição de Oaxaca-Blinder.

ResultadosNo total, 36529 alunos completaram o estudo (taxa de resposta: 91,32%), dos quais 50,79% eram meninos e 74,23%, habitantes urbanos. A idade média (DP) foi 12,14 (3,36) anos. A prevalência de sobrepeso, obesidade geral e obesidade abdominal foi 11,51%, 8,35% e 17,87%, respectivamente. A SSE com relação a sobrepeso, obesidade e obesidade abdominal foi -0,1, -0,1 e -0,15, respectivamente. O índice C com relação a sobrepeso, obesidade geral e obesidade abdominal foi positivo, o que indica que a desigualdade estava em favor de grupos de baixa SSE. A área de residência, o histórico familiar de obesidade e a idade foram os fatores que mais contribuíram para a desigualdade da prevalência de obesidade observados entre os grupos em SSE mais alta e mais baixa.

ConclusãoEste estudo fornece informações consideráveis sobre a alta prevalência de excesso de peso em famílias em SSE mais alta em nível nacional e subnacional. Esses achados podem ser utilizados para comparações internacionais e políticas de saúde, melhorando a programação ao considerar as diferenças em nível subnacional.

In recent years, the increasing prevalence of childhood obesity has become a health concern worldwide.1 According to a report by the World Health Organization (WHO), obesity is a major risk factor for non-communicable diseases including cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, and some types of cancer.2 Obesity, as a complex disorder, can be influenced by several factors. The relationship between socioeconomic status (SES) and obesity in children and adolescents has been well documented; however, conflicting results where observed according to the country's income.3 Most studies revealed that in low-and middle-income countries, obesity in children and adults has strong positive association with SES.4 In turn, an inverse association is observed in high-income countries.5 Moreover, some studies suggest that the relationship between SES and obesity may vary according to demographic factors search as age, gender, chronic disorders, and the region.6

The Middle East has one of the world's highest prevalence rates of obesity. Iran, as one of the countries in this region, is facing an increasing trend in obesity in children and adolescents, as confirmed by a recent meta-analysis.7 Health in childhood and adolescence is the basis of health in adulthood. Therefore, recognizing the factors that affect the prevalence of childhood obesity in relation to socioeconomic and demographic characteristics may provide a framework for policymakers and families to develop a health strategy for preventing obesity-related health consequences.

Previous studies in Iran have indicated a positive association between SES and obesity among adolescents8; however, no comprehensive national and provincial survey based on SES and demographic factors where retrieved for the Iranian pediatric population. Therefore, the objectives of the current study were: 1) to describe the prevalence of childhood obesity across the different regions of Iran; 2) to assess differences in the prevalence of overweight, generalized obesity, and abdominal obesity between school-aged children stratified into five levels of SES; and 3) to use Blinder–Oaxaca decomposition to determine how much demographics, screen time, physical activity, area of residence, and family history of obesity explain the inequality in obesity prevalence observed between highest and lowest levels of SES.

MethodsIn the present study, the authors analyzed combined data from the comprehensive national survey of school-based surveillance system entitled Childhood and Adolescence Surveillance and Prevention of Adult Non-communicable diseases (CASPIAN-IV) study,9 part focused on weight disorders.10

Overall, 40,000 school students were selected through multistage random cluster sampling in 2011–2012. They were aged 10–18 years, and lived in urban and rural areas of 30 provinces of Iran. By using the WHO-Global School-Based Student Health Survey (GSHS-WHO) instructions, trained healthcare experts followed all processes of examinations and inquiry with calibrated instruments. Information was recorded in the checklists and validated questionnaires for all participants.11 Aiming to provide the highest quality of data in multi-center data gathering, all levels of quality assurance were closely supervised and monitored by the Data and Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) of the project.9

DefinitionsDemographic informationDemographic information was collected for all participants through interview with one of their parents. These information included age, sex, residence area, family characteristics, family history (FH) of obesity, parental level of education, possessing a family private car, and type of home (private/rental), among others. Some complementary information on screen time, physical activity, and some other lifestyle habits were also collected.

Socioeconomic status (SES)Family SES was categorized according to the standard that was previously approved in the Progress in the International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) for Iran.12 Using principle component analysis (PCA), variables including parents’ education, parents’ job, possessing private car, school type (public/private), type of home (private/rental), and having personal computer in the house were summarized in one main component SES. SES was categorized into quintiles, in which the first quintile was the lowest SES and the fifth quintile, the highest.

Screen time (ST)In this study, ST was considered as the sum of the mean daily hours spent watching television or video, as well as leisure time using a personal computer (PC) or playing electronic games (EG). ST was asked separately for weekdays and weekends. For the analysis of correlates of ST, according to the international ST recommendations,13 this criteria was categorized into two groups: less than 2h per day (low), and 2h per day or more (high).

Physical activity (PA)For PA, the information of activities in the prior week to the study was collected. Participants reported the weekly frequency of their leisure time PA outside the school. For PA, two questions were asked: 1) “During the past week, on how many days were you physically active for over 30minutes?” (response options: from zero to seven days); and 2) “How much time do you spend in exercise class in school per week?” (response options: from zero to three or more hours). A frequency of less than two times per week was considered as low; two to four times a week was considered as moderate; and more than four times a week was considered as high.

MeasurementsWeight was measured to the nearest 200g, with the participant barefoot and wearing light clothes. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height squared (m2). Waist circumference (WC) was measured using a non-elastic tape to the nearest 0.1cm at the end of expiration, at the midpoint between the top of iliac crest and the lowest rib in standing position.9

Abdominal obesity was defined as WC ≥90th percentile value for age and sex. The BMI percentiles for the Iranian pediatric population were used; patients were considered underweight when <5th percentile; as normal weight, when between the 5th and 84th percentiles; as overweigh, when between the 85th and 94th percentiles; and as obese, when ≥95th percentile.14

Ethical concernsThe study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The ethics committees and other relevant national and provincial regulatory organizations approved the study.

After complete explanation of the objectives and protocols, participants and one of their parents were assured that their responses would remain anonymous and confidential. Participation in the study was voluntary and all of potential participants had the right to withdraw from the study at any time. Oral assent and written informed consent were obtained from students and one of their parents/legal guardians, respectively.

Statistical analysisContinuous data were presented as means (SD). Prevalence of weight disorders was reported with 95% confidence intervals (CI). The association of independent variables with excess weight was assessed using univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis. The results of logistic regression analysis were presented as OR (95% CI).

SES inequality in obesity was estimated by calculating the prevalence of obesity across SES quintiles, the concentration index (CCI), and the slope index of inequality (SII). To assess the association of obesity across SES quintiles, the CCI was used, which interpreted on the basis of the distribution of target variable versus SES distribution.15,16 CCI was estimated using the following equation:

where hi is the amount of obesity for the i-th individual, Ri is the relative rank of the i-th individual in the distribution of the SES variable, and μ is the mean value of the obesity. The negative and positive values of CCI show that inequality was in favor of high and low SES groups, respectively.16The decomposition of the gap in obesity between the first and fifth quintiles of SES was assessed using the Blinder–Oaxaca decomposition method.17 This method is based on two regression models, fitted separately for the two population groups (in this study, high and low economic groups):

where Y is the outcome variable; β is the coefficient including the intercept; X is the explanatoryvariable, and ɛ is the error. The gap between the two groups is calculated as:andThe first part of the right-hand side of the above equations is the observable difference in the variables in the two groups (the endowment or explained component), and the second part is related to the differences in the variable coefficients in the two groups (the coefficient or unexplained component). This technique divides the gap between the mean values of an outcome into two components. The explained or endowment component arises because of differences in the groups’ characteristics, such as differences in region or family size. An unexplained or coefficient component is attributed to different influences of these characteristics in each group.16 To perform the decomposition, a logistic regression model was constructed with independent variables in each economic group to determine the regression coefficients (β) as the main effect and their interactions with other independent variables.

Statistical measures were assessed using survey data analysis methods in the Stata software (version 11.1, Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA). p<0.05 was considered as statistically significant. Missing data were imputed using Amelia package version 1.7.3 in R statistical package (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Viena, Áustria). The Oaxaca command was performed in Stata software (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA).

ResultsOverall, 36,529 students participated in this survey (response rate: 91.32%). Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of students according to gender. The mean (SD) age of students was 12.14 (3.36) years; they consisted of 49.21% girls and 74.23% urban resident.

Demographic characteristics of students according to sex: the weight disorders survey of the CASPIAN-IV study.

| Total | Males | Females | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year)a | 12.14 (3.36) | 12.04 (3.39) | 12.25 (3.33) | <0.001 |

| Area of residenceb | ||||

| Urban | 26,989 (74.23) | 13,483 (73.10) | 13,506 (75.39) | <0.001 |

| Rural | 9371 (25.77) | 4961 (26.90) | 4410 (24.61) | |

| SESb | ||||

| Q1 | 6369 (20.0) | 3245 (20.09) | 3124 (19.92) | 0.13 |

| Q2 | 6391 (20.07) | 3240 (20.05) | 3151 (20.09) | |

| Q3 | 6374 (20.02) | 3227 (19.97) | 3147 (20.07) | |

| Q4 | 6337 (19.90) | 3140 (19.44) | 3197 (20.39) | |

| Q5 | 3304 (20.45) | 3063 (19.35) | 6367 (20.0) | |

| PAb | ||||

| Low | 14,652 (40.45) | 5629 (30.63) | 9023 (50.56) | <0.001 |

| Moderate | 16,019 (44.22) | 9070 (49.36) | 6949 (38.94) | |

| High | 5552 (15.33) | 3677 (20.01) | 1875 (10.51) | |

| STb | ||||

| Low | 23,965 (67.64) | 12,145 (67.45) | 11,820 (67.83) | 0.44 |

| High | 11,465 (32.36) | 5860 (32.55) | 5605 (32.17) | |

| FH of obesityb | ||||

| Yes | 24,790 (68.28) | 12,720 (69.08) | 12,070 (67.45) | 0.001 |

| No | 11,519 (31.72) | 5694 (30.92) | 5825 (32.55) | |

Q, quintile; SES, socioeconomic status; PA, physical activity; ST, screen time; FH, family history.

Supplementary material 1–3 present the socioeconomic inequality in the prevalence of overweight, obesity, and abdominal obesity in Iranian children and adolescents at national and provincial levels.

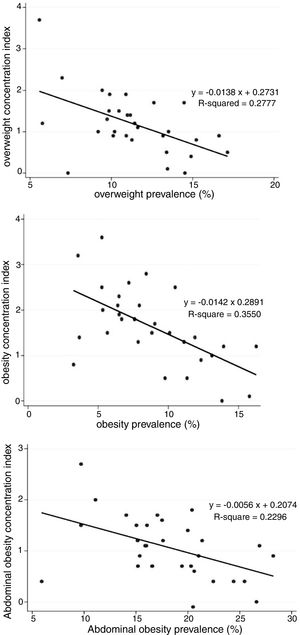

The estimations of the national prevalence of overweight, obesity, and abdominal obesity were 11.51% (95% CI: 11.16–11.86), 8.35% (95% CI: 8.05–8.66), and 17.87% (95% CI: 17.46–18.3), respectively. The prevalence of overweight, obesity, and abdominal obesity at national level presented unexpected changes between different SES quintiles. Based on the CCI, at national level the inequality for overweight, obesity, and abdominal obesity was in favor of low SES groups. The more detailed information regarding prevalence of overweight, obesity and abdominal obesity and their absolute and relative differences across the SES at provincial level are presented in supplementary material 1–3.

In supplementary material 4, the CCI of overweight, obesity, and abdominal obesity is mapped at the provincial level. Also, Fig. 1 shows the association of CCI with the prevalence of overweight, obesity, and abdominal obesity at the provincial level.

Table 2 presents the crude and adjusted association of independent variables with overweight, obesity, and abdominal obesity. In the adjusted model, students with higher SES had significantly higher odds of overweight, obesity, abdominal obesity, and excess weight (p<0.001).

Association of independent variables with overweight, obesity, and abdominal obesity in Iranian children and adolescents at national level in logistic regression model: the weight disorders survey of the CASPIAN-IV study.

| Variables | Overweight | Obesity | Abdominal obesity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | |

| SES(Q1) | ||||||

| Q2 | 1.33 (1.17–1.51)a | 1.27 (1.11–1.45)a | 1.22 (1.05–1.42)a | 1.18 (1.01–1.38)a | 1.30 (1.17–1.44)a | 1.22 (1.10–1.36)a |

| Q3 | 1.81 (1.60–2.04)a | 1.70 (1.49–1.93)a | 1.46 (1.26–1.69)a | 1.40 (1.21–1.64)a | 1.56 (1.41–1.72)a | 1.45 (1.30–1.61)a |

| Q4 | 2.03 (1.80–2.30)a | 1.84 (1.63–2.09)a | 1.90 (1.66–2.19)a | 1.79 (1.54–2.08)a | 1.91 (1.73–2.11)a | 1.70 (1.53–1.88)a |

| Q5 | 2.30 (2.04–2.58)a | 2.06 (1.82–2.34)a | 2.85 (2.50–3.26)a | 2.44 (2.11–2.81)a | 2.35 (2.13–2.58)a | 1.97 (1.78–2.18)a |

| PA (low) | ||||||

| Moderate | 0.96 (0.89–1.03) | 1.02 (0.94–1.10) | 1.04 (0.96–1.13) | 0.97 (0.88–1.07) | 0.98 (0.92–1.04) | 0.97 (0.91–1.03) |

| High | 0.84 (0.76–0.92)a | 0.90 (0.80–1.00) | 1.34 (1.20–1.48)a | 1.09 (0.97–1.23) | 1.07 (0.99–1.16) | 1.04 (0.95–1.13) |

| Sex (male) | ||||||

| Female | 1.01 (0.95–1.08) | 0.99 (0.92–1.06) | 0.70 (0.65–0.75)a | 0.70 (0.64–0.76)a | 0.84 (0.79–0.88)a | 0.82 (0.77–0.87)a |

| ST (≤2h) | ||||||

| >2h | 1.13 (1.05–1.21)a | 1.04 (0.96–1.12) | 1.03 (0.96–1.12) | 0.97 (0.88–1.06) | 1.07 (1.01–1.13)a | 1.00 (0.93–1.06) |

| Area of residence (urban) | ||||||

| Rural | 0.58 (0.54–0.63)a | 0.71 (0.65–0.79)a | 0.57 (0.52–0.63)a | 0.69 (0.62–0.77)a | 0.55 (0.51–0.59)a | 0.65 (0.60–0.70)a |

| FH of obesity (no) | ||||||

| Yes | 1.07 (1.00–1.14) | 1.07 (0.99–1.16) | 1.83 (1.70–1.97)a | 1.84 (1.69–2.00)a | 1.32 (1.25–1.39)a | 1.32 (1.25–1.41)a |

| Age (year) | 1.04 (1.03–1.05)a | 1.03 (1.02–1.04)a | 0.97 (0.96–0.97)a | 0.97 (0.96–0.98)a | 1.01 (1.00–1.02)a | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) |

Q, quintile; SES, socioeconomic status; PA, physical activity; FH, family history; ST, screen time.

When compared with boys, girls had lower odds of obesity (OR: 0.70; 95% CI: 0.64–0.76), and abdominal obesity (OR: 0.82; (95% CI: 0.77–0.87; p<0.001). Likewise, compared with urban inhabitants, participants from rural areas had lower odds of overweight (OR: 0.71; 95% CI: 0.65–0.79), obesity (OR: 0.69; 95% CI: 0.62–0.77), abdominal obesity (OR: 0.65; 95% CI: 0.60–0.70), and excess weight (OR: 0.68; 95% CI: 0.63–0.73; p<0.001).

Table 3 discloses that that 7.15% of the first quintile of SES group (low SES) and 15.20% of the last quintile of SES group (high SES) were overweight. This accounts for an 8.04% gap in favor of low SES group. Approximately 85% of this gap is related to the different effects of the variables studied in the two groups (unexplained component). That is, if the low SES groups were similar to the high SES group, in terms of the studied variables, the difference in overweight prevalence would decrease from 8.04% to 6.82%. In the explained part (Table 2), area of residence and age are significant, which indicate that they are the most effective variables responsible for the gap.

Decomposition of the gap in overweight, obesity, and abdominal obesity prevalence between the first and fifth quintiles of socioeconomic status in Iranian children and adolescents: the weight disorders survey of the CASPIAN IV study.

| Overweight | Obesity | Abdominal obesity | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prediction | |||

| % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | |

| Prevalence in first quintile | 7.15 (6.50,7.80)a | 5.17 (4.62,5.73)a | 12.08 (11.26,12.89)a |

| Prevalence in fifth quintile | 15.20 (14.30,16.09)a | 13.58 (12.72,14.44)a | 24.38 (23.30,25.45)a |

| Differences (total gap) | −8.04 (−9.15,−6.94)a | −8.41 (−9.43,−7.38)a | −12.30 (−13.65,−10.95)a |

| Due to endowments (explained) | |||

| PA | 0.02 (0.02,0.05) | 0.00 (−0.03,0.04) | 0.00 (−0.04,0.04) |

| Sex | 0.00 (−0.01,0.01) | −0.03 (−0.08,0.03) | −0.03 (−0.08,0.03) |

| ST | −0.12 (−0.30,0.06) | 0.03 (−0.12,0.19) | −0.15 (−0.36,0.07) |

| Area of residence | −1.15 (−1.64,−0.66)a | −1.13 (−1.59,−0.68)a | −2.10 (−2.72,−1.48)a |

| FH of obesity | −0.04 (−0.12,0.03) | −0.34 (−0.46,−0.22)a | −0.27 (−0.39,−0.16)a |

| Age | 0.07 (0.01,0.13)a | −0.05 (−0.10,−0.01)a | 0.00 (−0.03,0.03) |

| Subtotal | −1.22 (−1.76,−0.68)a | −1.52 (−2.01,−1.02)a | −2.54 (−3.21,−1.87) |

| Due to coefficients (unexplained) | |||

| PA | −0.30 (−0.72,0.12) | −0.06 (−0.47,0.36) | −0.50 (−1.03,0.03) |

| Sex | 2.37 (−0.99,5.73) | 6.20 (3.12,9.28)a | 10.64 (6.57,14.72)a |

| ST | −0.26 (−0.93,0.42) | −0.12 (−0.71,0.47) | 0.02 (−0.79,0.84) |

| Area of residence | 0.86 (−2.93,4.65) | −2.35 (−6.19,1.48) | −1.45 (−6.23,3.34) |

| FH of obesity | 0.18 (−0.63,0.98) | −1.96 (−2.75,−1.18)a | −0.36 (−1.37,0.64) |

| Age | −3.97 (−7.92,−0.03)a | 1.20 (−2.31,4.71) | −2.18 (−6.96,2.59) |

| Subtotal | −6.82 (−8.08,−5.56)a | −6.89 (−8.05,−5.73)a | −9.76 (−11.31,−8.21) |

PA, physical activity; FH, family history; ST, screen time.

The gap between the low and high SES groups for prevalence of obesity and abdominal obesity was 8.41% and 12.30%, respectively. In the explained component, area of residence, age, and family history of obesity made a significant contribution to the gap between the two SES groups for the prevalence of obesity. For abdominal obesity, area of residence and FH of obesity are the most effective variables responsible for the gap.

DiscussionThe findings of this study clearly indicate that, in Iranian children and adolescent, there is a positive association between socioeconomic inequalities and the prevalence of obesity at national and provincial levels. Similar trends were observed in some previous studies in developing countries.4 It is suggested that the higher prevalence of obesity in higher SES in Iran might be because of higher access to high-calorie foods, as well as higher frequency of sedentary habits. In turn, most studies in developed countries revealed an inverse association between SES and obesity. This might be due to the fact that consumption of vegetables and high-fiber diets are more common among the high SES than low-income families.18 A previous study demonstrated that the BMI in Iranian adolescents increased with consumption of fatty/salty snacks and fast foods, and decreased with consumption of fruits and vegetables.19 Changing dietary patterns, especially in the developing country, to energy-dense foods with high fat and sugar content and low fiber content is a well-observed nutrition transition phenomenon.20 In turn, in some countries, including Iran, “chubby” children are traditionally considered as attractive and as a sign of healthiness.21 These factors, especially in affluent families, might explain the higher prevalence of childhood obesity in families with higher SES observed in the current study.

In this study, the prevalence of excess weight (overweight and obesity) and abdominal obesity was high. This finding is consistent with a previous study by this group that demonstrated that the prevalence of abdominal obesity in Iranian children and adolescents was higher than that of general obesity.22 Moreover, in the current study boys showed higher risk of abdominal obesity and excess weight than girls. One of the causes of this difference can be the increasing importance of body image among girls. However, this finding is not consistent with a study conducted in children aged less than 10 years in 18 European countries, in which the prevalence of obesity was higher in girls than in boys.23 Similarly, a study among Swedish children and adolescents found a higher risk of overweight in girls when compared with boys.24 The present findings are in line with some other studies that showed higher risk of obesity in boys compared with girls.25 Generally, it is found that in developing countries, the prevalence of obesity and overweight in children and adolescents is higher among girls, whereas in developed countries, it is more prevalent in boys.26

In the current study, living in urban areas increased the risk of generalized obesity and abdominal obesity in children and adolescents. This finding is consistent with the majority of previous studies.27 Differences in lifestyle patterns can explain this phenomenon. It may be mainly linked to higher consumption of high-calorie foods and snacks,28 as well as with low physical activity due to motorized transport, low level of outdoor activities, and prolonged sedentary leisure time.29

The findings of this study indicate that the risk of overweight increased with age. This finding is consistent with a previous study, which also reported an inverse association between age and SES during childhood.30

The results of the current study clearly demonstrate the alarming prevalence of excess weight among children and adolescents at national and provincial level in Iran. In addition, the present findings revealed that obesity was strongly influenced by SES and demographic characteristics including gender, rural/urban residence, and age. Similarly to many other developing countries, in Iran the prevalence of childhood obesity is higher in those with higher SES. Nutrition transition, sedentary lifestyle, and cultural beliefs might be the possible reasons for the emergence of this trend. The current findings highlight the need for implementing primary prevention programs at national level that consider the inequalities at provincial level.

As study limitation, it should be noted that the causal relationship could not be assessed in the current study due to its cross-sectional design; more prospective studies are needed to evaluate the causality of the relationship of the independent variables with the studied outcome.

This study had several strengths. It has a large sample size, which allowed assessing the socioeconomic inequality in the prevalence of different outcomes in Iranian children and adolescents in national and even in provincial levels. Moreover, the differences in the prevalence of overweight, generalized obesity, and abdominal obesity were assessed between school-aged children at five SES levels. Finally, a sophisticated method, the Blinder–Oaxaca decomposition, was used to determine the contribution of different independent variables in the inequality of the prevalence of three different outcomes observed between the highest and lowest SES.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Kelishadi R, Qorbani M, Heshmat R, Djalalinia S, Sheidaei A, Safiri S, et al. Socioeconomic inequality in childhood obesity and its determinants: a Blinder–Oaxaca decomposition. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2018;94:131–9.