To review the literature on sialorrhea in children with cerebral palsy.

Source of dataNon-systematic review using the keywords “sialorrhea” and “child” carried out in the PubMed®, LILACS®, and SciELO® databases during July 2015. A total of 458 articles were obtained, of which 158 were analyzed as they were associated with sialorrhea in children; 70 had content related to sialorrhea in cerebral palsy or the assessment and treatment of sialorrhea in other neurological disorders, which were also assessed.

Data synthesisThe prevalence of sialorrhea is between 10% and 58% in cerebral palsy and has clinical and social consequences. It is caused by oral motor dysfunction, dysphagia, and intraoral sensitivity disorder. The severity and impact of sialorrhea are assessed through objective or subjective methods. Several types of therapeutic management are described: training of sensory awareness and oral motor skills, drug therapy, botulinum toxin injection, and surgical treatment.

ConclusionsThe most effective treatment that addresses the cause of sialorrhea in children with cerebral palsy is training of sensory awareness and oral motor skills, performed by a speech therapist. Botulinum toxin injection and the use of anticholinergics have a transient effect and are adjuvant to speech therapy; they should be considered in cases of moderate to severe sialorrhea or respiratory complications. Atropine sulfate is inexpensive and appears to have good clinical response combined with good safety profile. The use of trihexyphenidyl for the treatment of sialorrhea can be considered in dyskinetic forms of cerebral palsy or in selected cases.

Revisar a literatura referente a sialorreia em crianças com paralisia cerebral.

Fonte de dadosRevisão não sistemática utilizando as palavras-chave “sialorreia” e “criança” realizada nas bases de dados Pubmed®, Lilacs® e Scielo® em julho de 2015. Foram recuperados 458 artigos, 158 foram analisados por terem relação com sialorreia em crianças, 70 com conteúdo relativo à sialorreia na paralisia cerebral ou a avaliação e tratamento da sialorreia em outros distúrbios neurológicos foram aproveitados.

Síntese dos dadosA sialorreia tem prevalência entre 10% e 58% na paralisia cerebral e implica em consequências clínicas e sociais. É causada por disfunção motora oral, disfagia e distúrbio da sensibilidade intraoral. A gravidade e o impacto da sialorreia são avaliados através de métodos objetivos ou subjetivos. Estão descritas diversas formas de manejo terapêutico: treino para consciência sensorial e habilidades motoras orais, terapia farmacológica, injeção de toxina botulínica e tratamento cirúrgico.

ConclusõesO tratamento mais eficaz e que aborda a causa da sialorreia nas crianças com paralisia cerebral é o treino para consciência sensorial e habilidades motoras orais, realizado por um fonoaudiólogo. Injeção de toxina botulínica e o uso de anticolinérgicos têm efeito transitório e são auxiliares ao tratamento fonoaudiológico ou devem ser consideradas nos casos de sialorreia moderada a grave ou com complicações respiratórias. O sulfato de atropina tem baixo custo e parece ter boa resposta clínica com bom perfil de segurança. O uso de triexifenidil para o tratamento da sialorreia pode ser considerado nas formas discinéticas de paralisia cerebral ou em casos selecionados.

Sialorrhea is the involuntary loss of saliva and oral content1,2 that usually occurs in infants; however, at 24 months of age children with typical development should have the ability to perform most activities without loss of saliva.3 After the age of 4 years, sialorrhea is abnormal and often persists in children with neurological disorders, including neuromuscular incoordination of swallowing and intellectual disabilities.1 The term cerebral palsy (CP) describes a group of movement and posture development disorders, with activity restrictions or motor disabilities caused by malformations or injuries that occur in the developing fetal or child's brain.4,5 Worldwide, the prevalence of CP is 1–5 per 1000 live births, representing the most common cause of motor disability in children.6 The prevalence of sialorrhea in CP is seldom studied, and the results cannot be compared due to variation in the study designs and patient selection.1 Some authors reported a prevalence of 10–58%,7–10 thus it is reasonable to accept that one in three patients with CP has drooling at some degree.1

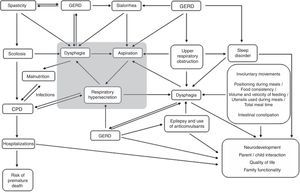

Although underestimated, sialorrhea implies clinical and social consequences and has several impacts related to the overall health of children with CP, regarding dysphagia and respiratory health, their socio-emotional development, and emotional and work overload for families and caregivers.

This non-systematic review aims to update the professionals involved in the care of children with CP in relation to the literature on sialorrhea in these patients; it was carried out using the keywords “sialorrhea” and “child” in the PubMed®, LILACS®, and SciELO® databases during July 2015. A total of 458 articles were retrieved, of which 158 were analyzed, as they were associated with sialorrhea in children; 70 were related to sialorrhea in cerebral palsy or the assessment and treatment of sialorrhea in other neurological disorders, which were also assessed.

Physiology of salivationThe parotid glands produce more serous, watery saliva as a result of stimulation during meals. The sublingual and submandibular glands produce more viscous saliva, more constantly, throughout the day.11,12 On average, a person swallows approximately 600mL of saliva every day; however, in some individuals, this volume can reach up to 1000mL/day.11 Afferents of the fifth, seventh, ninth, and tenth cranial nerves reach the solitary tract and salivatory nuclei in the medulla. The parasympathetic stimulation reaches the submandibular salivary glands through the seventh cranial nerve and the parotid through the ninth nerve.

The preganglionic sympathetic fibers originate at the lateral intermediate column of the first and second thoracic segments and connect with the postganglionic fibers in the upper cervical sympathetic ganglion. These postganglionic sympathetic fibers reach the salivary glands passing through the section along the external carotid artery. Salivary secretion is regulated indirectly by the hypothalamus-solitary circuit and by effects directly modulated by tactile, mechanical, and gustatory reflexes. It is questionable whether an interruption can occur in this regulatory mechanism as part of encephalopathy in CP.11 Sialorrhea may vary from minute to minute, depending on factors such as hunger, thirst, fatigue, anxiety, emotional state, and the circadian rhythm of salivary production.1

Predisposing factors, physiopathology, and etiologyReid et al. analyzed the predisposing factors of sialorrhea in children with CP (385 individuals) aged 7–14 years of age, which include the following: non-spastic types, the quadriplegic topographical pattern, absence of cervical control, severe difficulties in gross motor coordination/function, epilepsy, intellectual disability, lack of speech, open anterior bite, and dysphagia.13

Currently, it is widely accepted that sialorrhea in children with CP is not caused by hypersalivation, but by oral motor dysfunction, dysphagia, and/or intraoral sensitivity disorder.1,3,9,11,12 Senner et al. published a study that compared groups of children with CP with sialorrhea (n=14); children with CP without sialorrhea (n=14), and children with normal neurodevelopment (n=14) through quantification of saliva using the Saxon test described by Kohler et al. in 1985;14 the results showed lower scores in oral motor function without excess saliva production in the CP group with sialorrhea, suggesting that the hypersalivation is not one of the factors responsible for sialorrhea in CP.3 Erasmus et al. studied groups of children with CP (n=100) and healthy children (n=61) through collection of saliva using the method described by Rottevel et al.15 and concluded that there were no differences between salivary flow rates in both groups of patients.11

A proper swallowing reflex is essential for the swallowing of saliva. This complex, fundamental function is mediated by orofacial neuromuscular systems, and involves a series of sequential reflexes and coordinated movements of the muscles of the mandible, lips, tongue, pharynx, larynx, and esophagus.12 Several studies have shown a positive correlation between sialorrhea in children with CP and the following factors: difficulties in the formation of the food bolus,3,7 inefficient labial sealing, suction disorder, increased food residue,3,16 difficulty controlling the lips, tongue, and mandible,3,8 reduced intraoral sensitivity,3,17 reduced frequency of spontaneous swallowing,18 esophageal phase dysphagia,3,7 and dental malocclusion.3,19 Significant negative correlations have been found between sialorrhea and chewing capacity, as well as other swallowing skills in general.3 Other factors, all common in CP, influence the presence and severity of sialorrhea: open mouth position, inadequate body posture, particularly of the head, intellectual disabilities, emotional state, and degree of concentration.1,12,20

Association between sialorrhea and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)Saliva plays an important role in protecting the esophageal mucosa against lesions caused by GERD. In children with sialorrhea, the constant loss of saliva can impair the removal of gastric acid reflux into the esophagus, which can perpetuate esophageal dysmotility and esophagitis.3,21 Heine et al., in a study carried out in 1996, showed that approximately one-third of the 24 children with sialorrhea had evidence of GERD in the 24-hour pH monitoring or esophagoscopy. In this study, drug treatment with cisapride and ranitidine for GERD did not reduce the severity and frequency of sialorrhea in most children, and in the authors’ opinion, saliva secretion stimulated by GERD should have clinical significance only in those patients with significant esophagitis.21

For Erasmus et al., chemical irritation caused by GERD can lead to increased production of saliva through the mediation of the parasympathetic nervous system and vagovagal reflex, aiming to protect the oropharyngeal and esophageal mucosa. In children with oral motor dysfunction, this increase in saliva production could accumulate in the pharynx and/or esophagus, increasing the risk of aspiration. In the authors’ opinion, it is still a matter of debate whether GERD alone can cause severe sialorrhea and if GERD treatment can reduce its intensity in children with CP.10

Classification and clinical, social, and family implicationsFrom a clinical point of view, sialorrhea can be classified as anterior and posterior; both can occur separately or simultaneously. Anterior sialorrhea is the unintentional loss of saliva from the mouth. Posterior sialorrhea is the flowing of saliva from the tongue to the pharynx.1,10,22

Anterior sialorrhea can lead to psychosocial, physical, and educational consequences. One of them is social isolation, which can have negative effects on self-esteem. The most severely affected children may have an unpleasant odor, and may be rejected by their peers and even by their caregivers. Individuals may be perceived negatively and their intellectual capacity may be underestimated. The extent of this impact varies according to sociocultural characteristics, depending on age and cognitive ability. Severe anterior sialorrhea requires frequent changes of clothes and can damage books, computers, and keyboards, threatening essential education and communication tools. There can also be perioral infections and damage to the dentition.1,3,10,23–28 These consequences affect the lives of patients and also have an impact on the quality of life of families and caregivers. A Dutch group demonstrated the considerable demands placed on caregivers in terms of workload, such as having to frequently remind the individual to swallow saliva, clean the excess saliva on the mouth, chin, and other areas, and change and wash towels and clothes.27,28

Posterior sialorrhea occurs in children with more severe pharyngeal phase dysphagia. These children are at risk for saliva aspiration, which can cause recurrent pneumonia and may even go undiagnosed before significant lung injury develops.10 Park et al. described two cases in which saliva aspiration into the tracheobronchial tree was successfully documented through a radionuclide assessment known as a salivagram. This same method was used and showed a total reduction in saliva aspiration after botulinum toxin was applied to patients’ salivary glands.29 Vijayasekaran et al. studied a group of 62 children submitted to surgical treatment for sialorrhea, and showed an increase in the mean oxygen saturation and reduction in the frequency of pneumonia. Thus, therapeutic interventions can effectively improve respiratory health in these patients.30

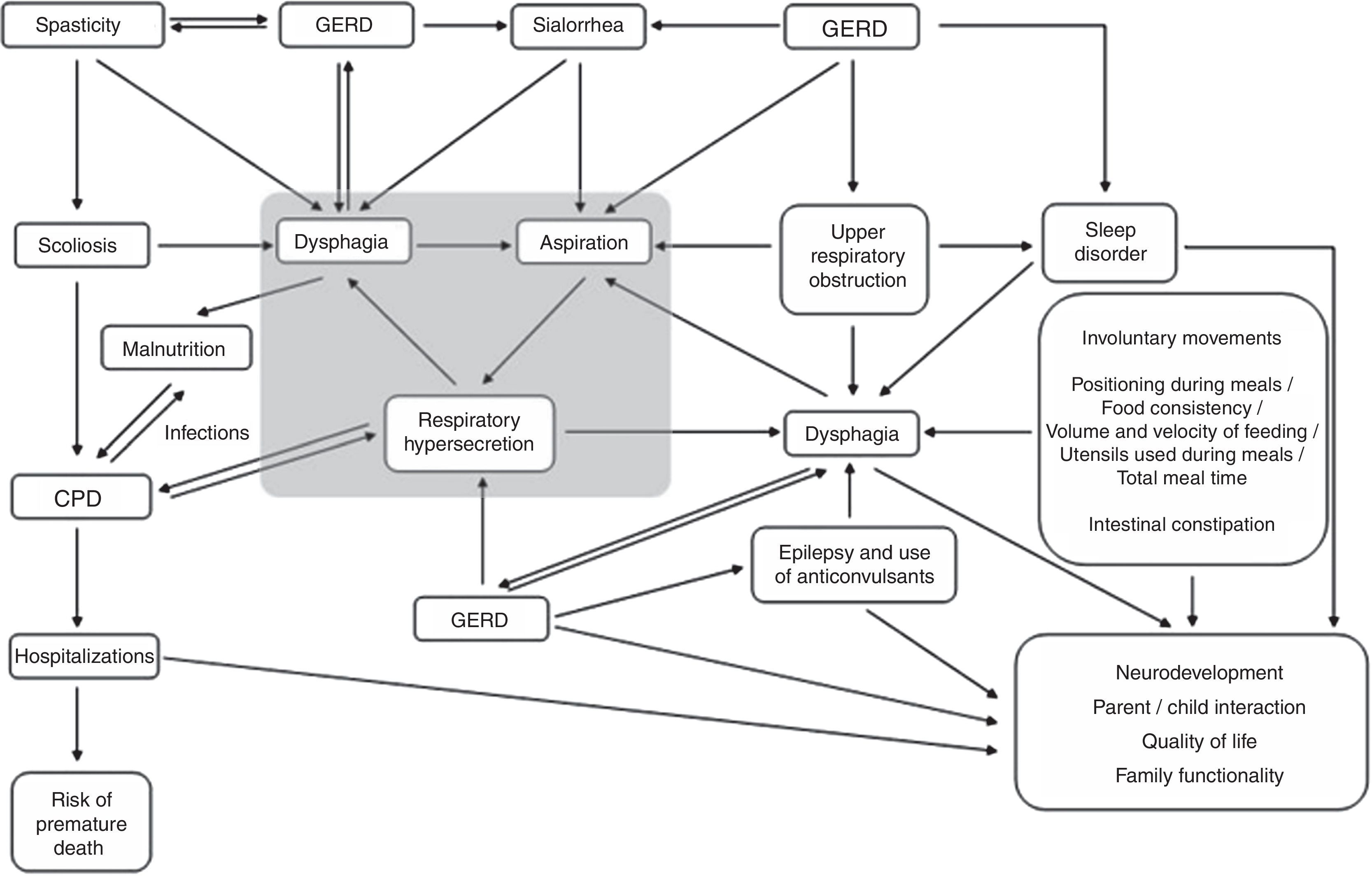

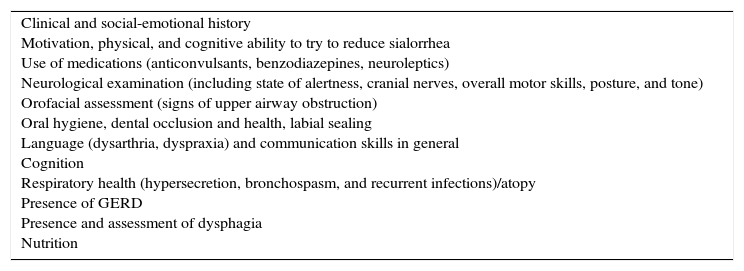

Sialorrhea assessmentClinical assessmentThe different clinical aspects involved in the health status of children with CP can influence the occurrence and severity of sialorrhea and, conversely, their severity can be influenced by their presence (Fig. 1). Therefore, when evaluating sialorrhea, these several factors (Table 1) should be actively assessed by history-taking and through observation of the child.1

Clinical factors to be investigated.

| Clinical and social-emotional history Motivation, physical, and cognitive ability to try to reduce sialorrhea Use of medications (anticonvulsants, benzodiazepines, neuroleptics) Neurological examination (including state of alertness, cranial nerves, overall motor skills, posture, and tone) Orofacial assessment (signs of upper airway obstruction) Oral hygiene, dental occlusion and health, labial sealing Language (dysarthria, dyspraxia) and communication skills in general Cognition Respiratory health (hypersecretion, bronchospasm, and recurrent infections)/atopy Presence of GERD Presence and assessment of dysphagia Nutrition |

GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease.

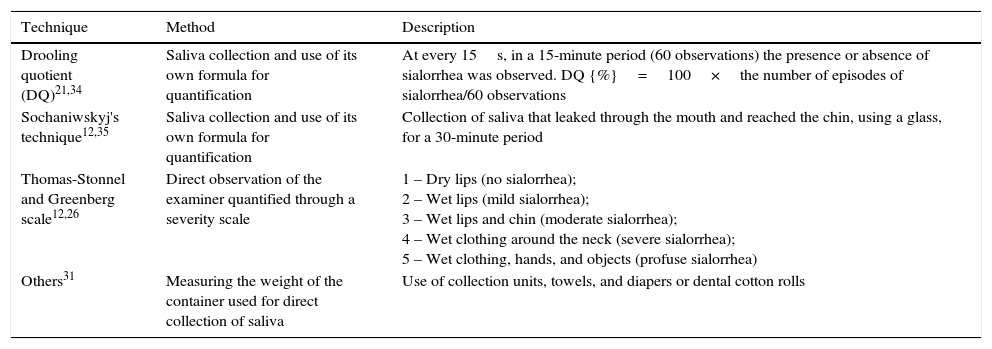

It is difficult to measure sialorrhea. The child must not realize that he/she is being observed and should be assessed during everyday situations. Nevertheless, it is necessary to quantify the frequency and severity of sialorrhea, as well as its impact on the quality of life of children and their caregivers. The severity and impact of sialorrhea can be evaluated through objective or subjective methods.31

Objective methods include measurement of salivary flow and direct observation of saliva loss; some of these techniques are described in Table 2.12,21,25,26,31–35 The development of direct (objective) measurement methods for anterior sialorrhea, which are validated and actually feasible, are still a challenge both in the research field and in clinical practice.31

Objective methods to measure sialorrhea.

| Technique | Method | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Drooling quotient (DQ)21,34 | Saliva collection and use of its own formula for quantification | At every 15s, in a 15-minute period (60 observations) the presence or absence of sialorrhea was observed. DQ {%}=100×the number of episodes of sialorrhea/60 observations |

| Sochaniwskyj's technique12,35 | Saliva collection and use of its own formula for quantification | Collection of saliva that leaked through the mouth and reached the chin, using a glass, for a 30-minute period |

| Thomas-Stonnel and Greenberg scale12,26 | Direct observation of the examiner quantified through a severity scale | 1 – Dry lips (no sialorrhea); 2 – Wet lips (mild sialorrhea); 3 – Wet lips and chin (moderate sialorrhea); 4 – Wet clothing around the neck (severe sialorrhea); 5 – Wet clothing, hands, and objects (profuse sialorrhea) |

| Others31 | Measuring the weight of the container used for direct collection of saliva | Use of collection units, towels, and diapers or dental cotton rolls |

Subjective scales are useful and appropriate methods to measure changes in sialorrhea, because the impact on families, caregivers, and the patients themselves is of utmost importance when assessing satisfaction with the effectiveness of any treatment. According to some researchers, the definitive method for evaluating the effectiveness of any treatment for sialorrhea is one that measures how much the life of the caregiver has been facilitated and that quantifies the improvement in the child's quality of life.33,36 Subjective scales such as the Drooling Rating Scale, the Drooling Frequency and Severity Scale, visual analog scales, and the Drooling Impact Scale31,33,36 are filled out by patients or their caregivers, which express their qualitative and quantitative impressions of the severity and impact of sialorrhea.31

TreatmentObjectivesThe main objectives in the treatment of sialorrhea are: reduction in social-affective and health impacts caused by anterior sialorrhea; reduction in health impacts caused by posterior sialorrhea; improved quality of life for patients and caregivers; and reduction in the burden experienced by caregivers.

Quality of life and burden on family/caregivers, self-esteem, and child's healthIn general, after several treatment modalities, the demands related to the care of these children are reduced, particularly regarding the frequency of the need to clean the mouth, lips, and chin; the number of changes of towels and clothes; and damage to books, school supplies, toys, and electronic equipment.36,37 Additionally, reduction in sialorrhea improves social contact between children and their peers. Even in children with intellectual disabilities, a German study has shown that the perception of parents concerning their children's satisfaction in relation to their physical appearance and life in general can improve after therapeutic interventions.36,38 van der Burg et al. published a study in which they evaluated changes in quality of life and necessity of care as a result of sialorrhea treatment. The impact of sialorrhea was investigated before and after treatment, using a questionnaire designed specifically for this study. The results demonstrated that the decrease in salivary flow had a significantly positive effect on the need for daily care. The authors conclude that reduced salivary flow should not be the only goal in the treatment of sialorrhea. It is recommended that the several therapeutic modalities be assessed in relation to the impact they bring to the patient's daily life.38

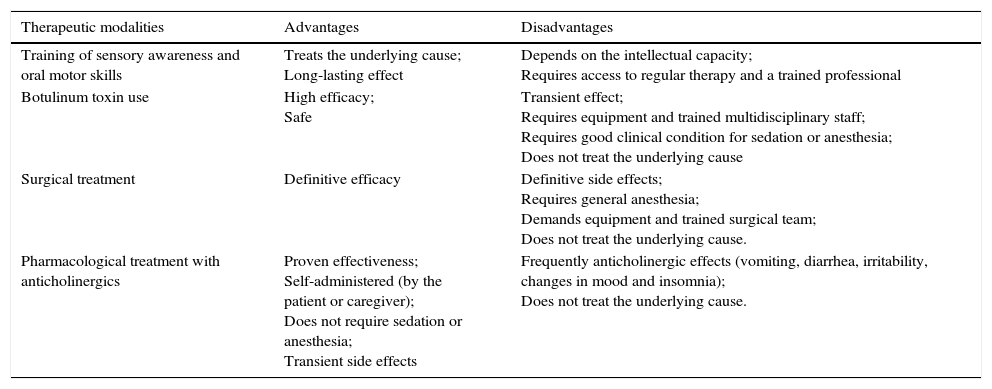

Therapeutic modalitiesThe literature describes several forms of therapeutic management. The advantages and disadvantages of the main treatment modalities are summarized in Table 3.

Advantages and disadvantages of the main therapeutic modalities.

| Therapeutic modalities | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Training of sensory awareness and oral motor skills | Treats the underlying cause; Long-lasting effect | Depends on the intellectual capacity; Requires access to regular therapy and a trained professional |

| Botulinum toxin use | High efficacy; Safe | Transient effect; Requires equipment and trained multidisciplinary staff; Requires good clinical condition for sedation or anesthesia; Does not treat the underlying cause |

| Surgical treatment | Definitive efficacy | Definitive side effects; Requires general anesthesia; Demands equipment and trained surgical team; Does not treat the underlying cause. |

| Pharmacological treatment with anticholinergics | Proven effectiveness; Self-administered (by the patient or caregiver); Does not require sedation or anesthesia; Transient side effects | Frequently anticholinergic effects (vomiting, diarrhea, irritability, changes in mood and insomnia); Does not treat the underlying cause. |

For children capable of obeying commands and cooperating with the training, this is the foundation of intervention and should be tested before other treatment options. Initial maneuvers include improvements in the sitting position, lip movements, and closing of the mandible and tongue. In its simplest form, it consists of exercises that are carried out in a playful manner, such as the use of different textures around the mouth (ice cubes, electric toothbrush, etc.) to stimulate sensory awareness and exercises to improve lip sealing and tongue movement (using a straw, lipstick kisses on paper, filling party balloons, etc.). The constant guidance of the speech therapist is necessary. Unlike children with more severe neurological symptoms and less capacity for cooperation and understanding, those with mild sialorrhea can achieve significant benefits through such a program.39

Body modification through biofeedbackBody modification through biofeedback is based on the monitoring of the target muscle group for electromyographic stimulation. When the muscle contracts, electromyography informs of the change in muscle activity through acoustic or light signals. Thus, the patient can consciously correct or improve certain components of swallowing. The technique can have a positive impact on patient training and improving oromotor function.12,20

Orthodontic therapyIt should be used as complementary to any other treatment, and aims to prevent or correct an anterior open bite and other vertical occlusion abnormalities.12

Pharmacological and surgical therapiesDespite indications that hypersalivation is not one of the factors responsible for sialorrhea in children with CP, most available treatments – including the use of oral (OR), transdermal (TD), and sublingual (SL) medications, botulinum toxin, or surgical management – aim at the reduction in saliva production.3

There are advantages and disadvantages to the use of these techniques (Table 3) when compared with nonpharmacological and nonsurgical treatments. In general, the options aimed at reducing salivary production quickly lead to an effective reduction in sialorrhea, but with a profile of side effects inherent to each treatment modality. Another important aspect is related to the possible exacerbation of GERD and esophagitis.3 Therefore, in those patients undergoing a treatment whose mechanism of action is to reduce salivary production, early and effective GERD treatment becomes essential. In this group of treatments, each type has its peculiarities, as described below.

Botulinum toxinThe intraglandular injection of botulinum toxin inhibits the release of acetylcholine from cholinergic nerve terminals, thereby reducing salivary secretion and sialorrhea. Some prospective, controlled studies have investigated the use of botulinum toxin type A (BoNTA) for the treatment of sialorrhea. A significant reduction in sialorrhea was observed in these studies using objective (Class I) and subjective control scales. The injection sites are the parotid and submandibular glands. Older children (cooperative) and adults may undergo local anesthesia.1,40,41 Some disadvantages (Table 3) hinder patients’ access to the procedure: the injection sites should be accessed, ideally, by ultrasound; the technique requires the presence of medical and nursing staff with experience; and it should be assessed whether the patient meets the clinical requirements to undergo sedation or anesthesia.

Surgical treatmentThe first surgical treatment for sialorrhea was parotid ductal relocation,42 followed by further removal of submandibular glands.43,44 Radical procedures such as bilateral division of the parotid ducts with removal of the submandibular glands and neurectomies have been proposed, but with unpredictable results.43–48 Surgeries were carried out mostly in adults, and their efficacy was questionable, as symptoms recurred after some time.43,44 In 1974, Ekedahl described the rearrangement of ducts from the submandibular glands into the tonsilar fossa.49 The glands maintained their function with normal passage of saliva to the oropharynx, preventing the accumulation of saliva in the anterior mouth floor, ensuring the presence of saliva in the oral cavity, while keeping its contribution to the swallowing process. Over the subsequent years, it has undergone few modifications (the removal of the sublingual glands is performed concomitantly) and it has become the surgical technique of choice for severe sialorrhea.44,49 Due to the risk of permanent consequences (especially xerostomia), it is indicated only in severe cases, those non-responsive to non-surgical therapies and in which sialorrhea has great impact on the health and quality of life of the children and family members/caregivers.1

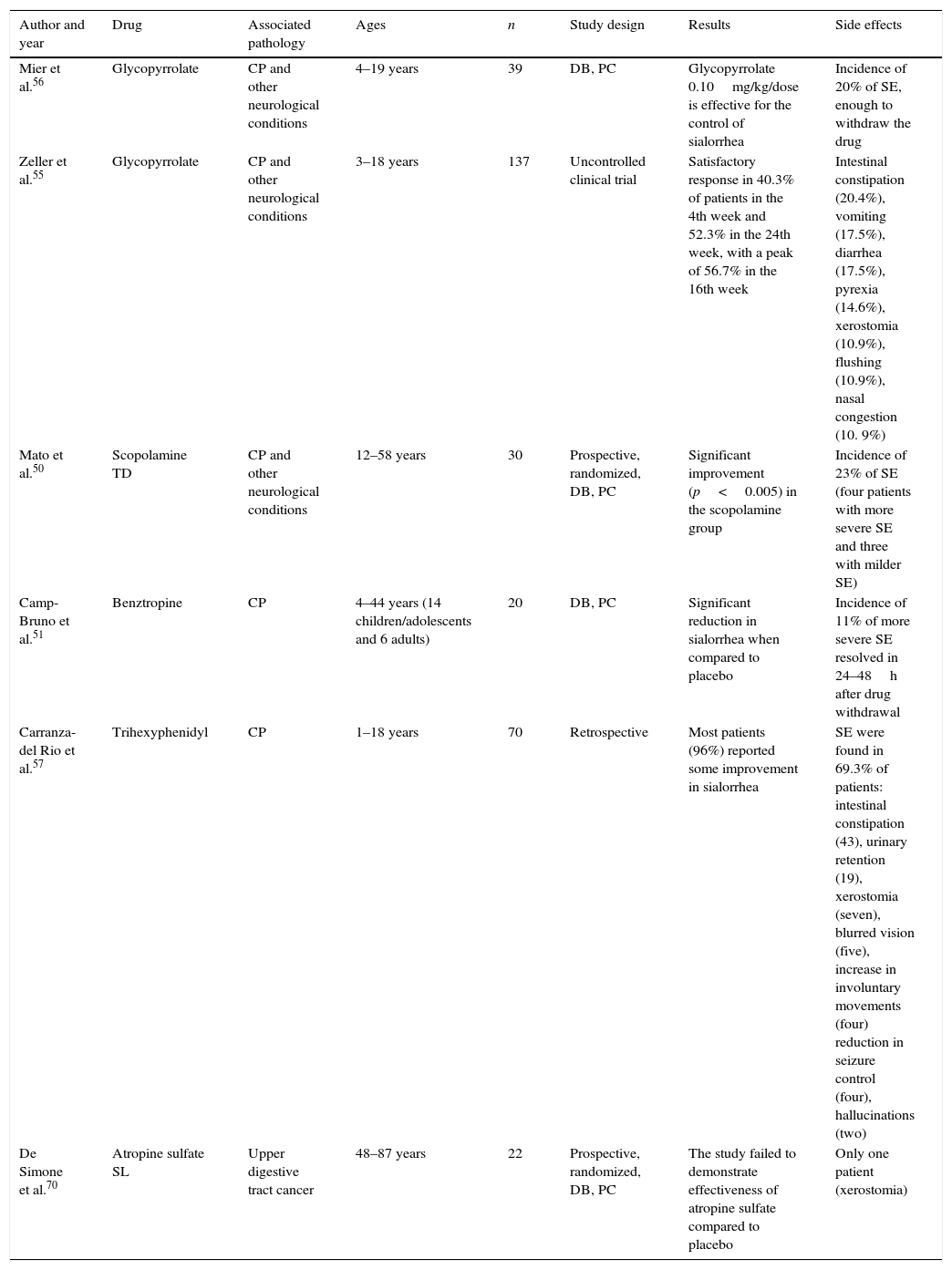

Oral, transdermal, or sublingual drug treatmentThe salivary glands are controlled by the parasympathetic autonomic nervous system and, therefore, anticholinergic drugs induce a significant reduction in salivary flow, being the most often used drugs. The advantages and disadvantages of the oral (OR), transdermal (TD), or sublingual (SL) use of anticholinergic drugs are summarized in Table 3.12,50–57 The most widely used systemic anticholinergic drugs are glycopyrrolate, benztropine, scopolamine, atropine, and trihexyphenidyl; however, only trihexyphenidyl and atropine sulfate are available in Brazil; the results of some studies with these drugs are summarized in Table 4.

Pharmacological treatment.

| Author and year | Drug | Associated pathology | Ages | n | Study design | Results | Side effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mier et al.56 | Glycopyrrolate | CP and other neurological conditions | 4–19 years | 39 | DB, PC | Glycopyrrolate 0.10mg/kg/dose is effective for the control of sialorrhea | Incidence of 20% of SE, enough to withdraw the drug |

| Zeller et al.55 | Glycopyrrolate | CP and other neurological conditions | 3–18 years | 137 | Uncontrolled clinical trial | Satisfactory response in 40.3% of patients in the 4th week and 52.3% in the 24th week, with a peak of 56.7% in the 16th week | Intestinal constipation (20.4%), vomiting (17.5%), diarrhea (17.5%), pyrexia (14.6%), xerostomia (10.9%), flushing (10.9%), nasal congestion (10. 9%) |

| Mato et al.50 | Scopolamine TD | CP and other neurological conditions | 12–58 years | 30 | Prospective, randomized, DB, PC | Significant improvement (p<0.005) in the scopolamine group | Incidence of 23% of SE (four patients with more severe SE and three with milder SE) |

| Camp-Bruno et al.51 | Benztropine | CP | 4–44 years (14 children/adolescents and 6 adults) | 20 | DB, PC | Significant reduction in sialorrhea when compared to placebo | Incidence of 11% of more severe SE resolved in 24–48h after drug withdrawal |

| Carranza-del Rio et al.57 | Trihexyphenidyl | CP | 1–18 years | 70 | Retrospective | Most patients (96%) reported some improvement in sialorrhea | SE were found in 69.3% of patients: intestinal constipation (43), urinary retention (19), xerostomia (seven), blurred vision (five), increase in involuntary movements (four) reduction in seizure control (four), hallucinations (two) |

| De Simone et al.70 | Atropine sulfate SL | Upper digestive tract cancer | 48–87 years | 22 | Prospective, randomized, DB, PC | The study failed to demonstrate effectiveness of atropine sulfate compared to placebo | Only one patient (xerostomia) |

DB, double-blind; CP, cerebral palsy; PC, placebo-controlled; SE, side effects.

The oral solution of glycopyrrolate is currently the only formulation of an anticholinergic drug approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat sialorrhea in children aged 3–16 years. Glycopyrrolate is not available in Brazil.

ScopolamineSeveral studies have shown a reduction in saliva secretion with use of scopolamine. The transdermal route effectively reduces salivary secretion in approximately 67% of patients and its action can be demonstrated 15min after the transdermal patch is applied. The main side effects are pupil dilation and urinary retention.53 Lewis et al. observed that 66% of the patients had pupil dilation, which occurred a few days after the start of the treatment.52

BenztropineThere has been only one study with benztropine involving children. The drug was considered effective in a controlled, randomized clinical trial published by Camp-Bruno et al.51

TrihexyphenidylIn the largest study in children with trihexyphenidyl, a drug commonly used in the treatment of extrapyramidal syndromes such as dystonia, the indications for use were dystonia (28.7%), sialorrhea (5.9%), and dystonia and sialorrhea (65.4%). The initial mean dose was 0.095mg/kg/day and the maximum mean dose was 0.55mg/kg/day, two to three times a day. Side effects were found in 69.3% of patients. Most patients reported some improvement in dystonia, sialorrhea, and specific language. The authors concluded that trihexyphenidyl was better tolerated in this population of children and adolescents (with CP and extrapyramidal syndrome) when compared to the adult population, and that improvement in sialorrhea may have occurred due to the anticholinergic effect of the drug, but also through central action, resulting in greater control motor of muscles involved in swallowing.57 Other studies have reported the successful use of trihexyphenidyl in adults to treat sialorrhea induced by clozapine.58–60

Atropine sulfateAlthough atropine has been for many years acknowledged as effective, it has never been widely accepted for the treatment of chronic sialorrhea.54 The first mention of its use for treatment of sialorrhea was made in an article published in October 1970 by Smith et al. in the New England Journal of Medicine.61 Subsequently, some studies reported its use to treat drug-induced sialorrhea62–68 and patients with Parkinson's disease.69 De Simone et al. published the only prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled, double blind study with atropine SL, which failed to demonstrate effectiveness of atropine when compared to placebo.70 In 2010, Rapoport reported the case of 14-year old boy with metachromatic leukodystrophy and excess oral secretions who needed frequent aspirations, which caused recurrent drops in oxygen saturation caused by saliva aspiration, successfully treated with atropine sulfate SL, representing the only reported case in the literature on atropine sulfate SL in children or adolescents.54

There are no specific studies published in children with CP, but there is ongoing research using atropine SL (0.5% eye drops) in children with CP, which suggests good efficacy with low incidence of side effects. Such data will be available for publication soon.

Final considerationsIn practice, to indicate any type of treatment for sialorrhea in children with CP, one should take into account the patient's access to the proposed treatment, as well as the socioeconomic and cultural characteristics of each family, in order for the individual choice of methods to be efficient, more specific, and to be less of a burden for each patient/family. The most effective treatment and the one that effectively addresses the cause of sialorrhea in children with CP is training of sensory awareness and oral motor skills, performed or supervised by a trained and qualified speech therapist.

Drug therapies, such as the use of botulinum toxin and anticholinergics, have a transient effect and should ideally be adjuvant to speech therapy, or should be considered in specific cases of patients with moderate to severe sialorrhea or respiratory complications. Among the available drugs, atropine sulfate is a low-cost, easy-access drug and appears to have good clinical response with good safety profile. The use of trihexyphenidyl for the treatment of sialorrhea in children may be considered for dyskinetic forms of CP or in some selected cases.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.