To identify the differences between the prevalence and factors associated with involvement in bullying among schoolchildren from Recife, in the role of victim and perpetrator.

MethodThis is an epidemiological, cross-sectional, analytical study, with a probabilistic cluster sample of 1,402 students enrolled in high schools in Recife. Data analysis consisted of a descriptive analysis, followed by the application of Pearson's chi-squared test with statistical significance of 0.05 and 95% confidence interval. For the association analysis, multilevel modeling was used to control the cluster effect.

ResultsIt was observed that adolescents who feel different from other peers were associated with bullying, regardless of the role played. Being a victim was associated with being female, having low self-esteem, and using tranquilizers; being a transgressor was a protective factor. As for the role of perpetrator, being male, excessive alcohol consumption, having poor school performance, being a transgressor, and accepting peer violence were the associated variables; in turn, not defending their ideas when among friends showed to be a protective factor for bullying.

ConclusionThe differences between the adolescents, whether in the role of victim or perpetrator, indicate that the advocacy and prevention actions should focus on these aspects, mainly in the school environment.

Identificar as diferenças entre prevalências e os fatores associados ao envolvimento em bullying entre adolescentes escolares do Recife no papel de vítima e agressor.

MétodoEstudo epidemiológico de corte transversal analítico, com amostra probabilística por conglomerados de 1.402 estudantes matriculados no ensino médio de escolas do Recife. A análise dos dados foi constituída de uma análise descritiva, seguida da aplicação do teste de Qui-Quadrado de Pearson com significância estatística de 0,05 e Intervalo de Confiança de 95%. Para a análise de associações foi empregada a modelagem multinível para controle do efeito do conglomerado.

ResultadosObservou-se que o adolescente que se sente diferente dos outros colegas apresentou associação com o bullying independente do papel desempenhado. A condição de ser vítima mostrou associação com ser do sexo feminino, ter baixa autoestima e utilizar tranquilizantes, além disso, ser transgressor mostrou ser fator de proteção. No papel de agressor de bullying ser do sexo masculino, fazer uso de álcool em excesso, ter um ruim desempenho escolar, ser transgressor e aceitar violência entre pares foram as variáveis associadas; por sua vez, não defender suas ideias com amigos revelou ser fator de proteção para prática do bullying.

ConclusãoAs diferenças apresentadas entre os adolescentes, seja no papel de vítima ou de agressor, apontam que condutas de promoção e prevenção tenham enfoque que considerem tais aspectos principalmente no ambiente escolar.

Violence among schoolchildren is a worldwide problem of great relevance to public health, representing a critical and challenging issue due to the social and developmental impact on those involved.1 The reality of Brazilian schools is no different, and these manifestations have taken frightening proportions nowadays.2

In the school environment, there is a specific category of violence or aggressive behavior known as bullying, which is a subcategory of peer violence with specific characteristics, such as intentional behavior, repetition, and power imbalance.3 This phenomenon has four types of involvement: victims, perpetrators, victim-perpetrators, and witnesses.4

Among the involvement roles, the victims stand out, who are individuals who have repeatedly experienced an intentional aggression, and who think they have at least one characteristic, whether physical, social, or psychological, that puts them in a situation of power imbalance in relation to their aggressor,5 while the perpetrators are individuals who assault others, without necessarily being provoked by the victim.5 They sometimes feel that their conduct can bring material and social benefits, and are usually popular.

Bullying is a practice that leads to short-term to long-term behavioral, physical, and emotional problems for those involved.6 The literature has indicated that the consequences of the involvement differ according to the role played, among which are those observed in victims: difficulties in school activities and relationships, presence of mental disorders in adulthood, decreased self-esteem, greater propensity to drop out of school,7 self-mutilation, and suicidal behavior.8 For the perpetrators, this exposure can lead to problems in affective and social relationships, difficulty in respecting the laws, less self-control, and greater likelihood of becoming more aggressive and becoming involved in criminality.7

Data from a study conducted in 40 countries with 202,056 school adolescents found a prevalence of 12.6% for bullying victims and of 10.7% for perpetrators.9 Studies carried out with Brazilian schoolchildren have found a prevalence of bullying victims ranging from 7.1% to 37.6%6,10,11 in public schools and from 7.6% to 35% in private ones.6,11 The prevalence of bullying perpetrators ranged from 15% to 39.7%.6,12,13 Thus, there is a wide variation in prevalence between studies, a fact that may be related to the different bullying classification criteria and the use of different scales when measuring it, in addition to the social contexts where this phenomenon occurs.

The literature points out that the damage and consequences resulting from exposure to this phenomenon are numerous, but they may vary according to the role played. However, it is noteworthy that most studies carried out on this topic were concerned with the analysis of risk and protective factors separately, and only regarding the victims. Therefore, this study is important, as it estimates the magnitude of this problem and identifies the factors associated with the condition of bullying victim and perpetrator among school adolescents from the city of Recife.

MethodsThis research is part of a larger study entitled “Bullying among school-aged adolescents: a bioecological approach,” approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Instituto Aggeu Magalhães, under CAAE registration No. 33233014.6.000.5190 and Plat Br Opinion No. 745.886, according to the norms of Resolution 466/12 of the National Health Council on research involving humans.

This is a cross-sectional epidemiological analytical study, which allowed estimation of the prevalence and identification of the differences between the personal characteristics of bullying victims and perpetrators by applying a questionnaire, consisting of scales and questions about bullying and risk factors associated with adolescents, aged 15–19 years, enrolled in the second year of high school in public and private schools in Recife, state of Pernambuco, Brazil, who attended school during daytime. The use of students attending the second year of high school is due to the need to approach a population with greater maturity and understanding to answer the questions about violence contained in the questionnaire; at the same time, it was decided to avoid the third year, which is academically overloaded due to the proximity to the selection processes for higher education (college/university).

The sample size calculation was performed with an estimated population of 20,404 students attending the second year of high school (15–19 years), according to data provided by the Pernambuco State Board of Education in 2013. This study applied a confidence interval of 95%, a sampling error of five percentage points, an estimated prevalence of 30% among the students, 20% sample loss, and the sample design effect was set at twice the minimum sample size. The estimate obtained was 625 students from public schools and 625 from private ones. Considering 20% loss, the total sample consisted of 1563 students.

The sampling was performed by clusters and followed a sequence of stages, in an attempt to obtain a representative sample of students regarding the distribution according to the type of school and grade. At the first stage, the parameters used to estimate the number of schools according to the government level were prevalence of bullying in 95% of schools, sampling error=10%, and design effect=1, resulting in an estimate of 32 schools, 16 public schools and 16 private ones. Expecting 20% loss, the final sample included a total of 40 schools equally distributed in both strata.

At the second stage, the classes were randomly drawn within each school. To reach the expected number of participants, approximately 40 questionnaires were applied in each school.

This article analyzed issues about the bullying victim and perpetrator, classified as the dependent variable, and personal characteristics were considered independent variables. The involvement in bullying as the victim was defined based on the California Bullying Victimization Scale (CBVS),14 which consists of seven items that inquire about the types and frequency of victimization episodes the students may have experienced at school, considered examples of bullying behavior. Each scale item consists of a sequence of five points, classified as: 0 = never, 1 = only once last month, 2 = two or three times last month, 3 = only once during this week, and 4 = several times during this week. Subsequently, it is necessary to indicate whether this previously classified behavior was purposeful and important (hurt him/her) by answering “yes” or “no.” Finally, the CBVS assesses the power imbalance between the victim and the perpetrator through ten characteristics that can describe what the other person is like, asking individuals to compare themselves to the “main person who did such things to you” through answers to the three-point scale, classifying as: “less than me”, “like me,” and “more than me.” Therefore, adolescents who experienced some type of victimization two or three times a month or more were considered victims of bullying.

Regarding being considered a bully, it was evaluated based on the question based on the Olweus15 concept and the CBVS,14 as described below: “Among your classmates, is there anyone who you consider inferior to you? If so, answer the next question thinking only about that person. Have you ever done things on purpose to hurt your classmate, such as: A) Mocking, cursing or giving nicknames? B) Spreading rumors or gossip, ignoring or leaving him/her out of your group? C) Pushing, physically assaulting, threatening, or damaging his/her things?” The following answer options were available for each item: 0. Never; 1. Only once last month; 2. Two or three times last month; 3. Only once during this week; 4. Several times during this week. The individual who marked one of items 2, 3, or 4 in any of the alternatives was considered a bully.

The classification “victim-perpetrator” was determined considering the classification, at the same time, of the above description of victim and perpetrator; i.e., if the student answered having suffered some kind of intentional violence at least two or three times in the previous month, which hurt him/her, made by a classmate with different characteristics from his/hers, and at the same time answering that he/she bullied someone at least two or three times in the previous month.

Regarding the independent variables, some were assessed by isolated questions and others by scales, as described below: Gender: self-reported as female or male; Age: self-reported as between 15 and 19 years old; Skin color/ethnicity: self-reported as white, black, brown, yellow, or indigenous; Religious practice: self-reported; Having a physical disability: self-reported; School performance: The student was asked about his/her grades in the last year. The response options were: very good, good, bad, and very bad. Self-esteem: It is a tool consisting of ten items designed to globally assess the positive or negative attitude towards oneself. There are four types of response options: totally agree, agree, disagree, totally disagree. A high score indicates high self-esteem. The version used in this study was adapted in Brazil by Avanci et al. in 200716; Self confidence/defend their ideas or opinions: It was assessed based on the question of whether the adolescent defends their ideas and opinions with their friends/classmates; Drug use by the adolescent in the previous year: Categorized as the absence or presence of at least one of the following behaviors: alcohol consumption until getting intoxicated (getting “drunk”); use of cannabis, cocaine, crack, or cocaine paste, weight loss medication, downers/tranquilizers, or anabolic steroids (“drugs to make you stronger”). The response options were: often, a few times, and never; Feeling different: The adolescents were asked if they had any characteristics that made them feel different; Excess weight: Students answered if they thought they had excess weight and if they had suffered any discrimination or humiliation for it; Young offender: Part of United Nations Latin American Institute for the Prevention of Crime and the Treatment of Offenders (ILANUD/UN) tools on self-reported violations.17 It consists of nine dichotomous questions (yes/no) about acts performed in the past year: falsifying someone’s signature on documents, purposely damaging others’ possessions, severely assaulting someone, humiliating someone by showing superiority, taking part in a fight in which a group of friends fight against another group, carrying a cold weapon, carrying a firearm, theft; Sexual orientation: A question from an adapted version of the Minnesota Adolescent Health Survey by Berlan et al., 2010,18 was used. This question was also translated into Portuguese and adapted for use in this research. The students were asked how they felt about their sexual orientation, answering according to five options: 1. Fully heterosexual, 2. More heterosexual, 3. Bisexual, 4. More homosexual, and 5. Fully homosexual. The answers were categorized for analysis in three groups: Heterosexual (1), Bisexual (2, 3, and 4), and Homosexual (5); Having siblings: Question about whether the adolescent had siblings, with the response options: yes and no; Accepting peer violence: The students were asked how they felt about the acts: “boy humiliating boy,” “girl humiliating girl,” “boy physically assaulting boy,” “girl physically assaulting girl,” and “brawling between peers” regarding the relationship between adolescents. Students who answered “not serious” were considered as accepting of violence, while adolescents who answered “very serious” and “serious” when responding about these acts were considered as not accepting of peer violence.

All assessed variables and tools used in this study are described in Table 1.

Description of variables, operationalization and categorization of the studied variables.

| Variable | Operationalization | Categorization |

|---|---|---|

| Dependent | ||

| Bullying | California Bullying Victimization Scale, adapted and validated by Soares in 2015,14 plus a question developed by the author | 1. Victim 2. Perpetrator |

| Independent | ||

| Gender | Self-reported | 1.Female 2.Male |

| Age (in years) | Self-reported | (15–16) |

| 17–19 | ||

| Skin color/Ethnicity | Self-reported | 1.White 2.Black 3.Yellow/Indigenous |

| Having a physical disability | Self-reported | 1.Yes 2.No |

| Religious practice | Self-reported | 1.Yes 2.No |

| School performance regarding grades | Self-reported | 1 (1.Very good and 2.Good) 2 (3.Bad and 4.Very Bad) |

| Self-esteem | Rosenberg scale adapted in Brazil by Avanci et al. 200716 | 1.Low self-esteem 2.High self-esteem |

| Feeling different | Self-reported | 1.Yes 2.No |

| Self-confidence (defending one’s ideals and opinions) | Self-reported | 1. Does have 2. Does not have |

| Excess alcohol consumption | Self-reported | 1.Yes 2.No |

| Use of illicit drugs | Self-reported | 1.Yes 2.No |

| Use of medications to lose weight | Self-reported | 1.Yes 2.No |

| Downers/Tranquilizers | Self-reported | 1.Yes 2.No |

| Anabolic drugs | Self-reported | 1.Yes 2.No |

| Excess weight | Self-reported | 1.Yes 2.No |

| Being a transgressor | ILANUD/UN tool about self-reported violations17 | 1.Yes 2.No |

| Sexual orientation | Question fromthe Minnesota Adolescent Health Survey,adapted by Berlan in 20108 | 1.Heterosexual 2.Bisexual and Homosexual |

| Having siblings | Developed question | 1.Yes 2.No |

| Accepting peer violence | Developed question | 1.Yes 2.No |

ILANUD/UN, United Nations Latin American Institute for the Prevention of Crime and the Treatment of Offenders.

Data collection took place in 18 public and 18 private schools, between August and November 2014. The days and times of collection were previously scheduled with the coordination of each school.

To apply the questionnaires, permission was requested from the principals of the selected schools, who signed an informed consent. Adolescents aged 18–19 years were asked to sign an informed consent to participate in the research, as recommended in Resolution 466/12 of the National Health Council, which regulates research with humans.

Adolescents aged 15 to 17 years were asked to sign a term of assent to participate in the study. In this case, the parents were not consulted, since the research would address issues related to violence suffered by the adolescent in the domestic environment, and often in this type of violence the main perpetrators are the fathers, mothers, and other guardians, such as stepparents. This issue is common in studies on violence against children and adolescents, and is supported by the CFP Resolution No. 016/2000. Anonymity was guaranteed to all participants, and students were informed that they were free to withdraw from the study at any time.

After the research was explained and the term of assent was signed, the questionnaires were applied by a team of two researchers from LEVES who provided a brief explanation about completing the questionnaire and who remained in the classroom throughout the process. The questionnaire took an average of 60min to be completed in each class.

A total of 1411 students participated in the survey; however, nine of them did not adequately complete the questionnaire, thus totaling 1402 adolescents who participated in the study.

For data analysis, masking was used for tabulation in the database, which were entered into the Epi-Info program (Epi: A Package for Statistical Analysis in Epidemiology. R package version 2.38. URL) by double typing. Thus, after consolidation and validation of the entered data, the analysis was performed using STATA software (Stata Statistical Software: Release 12. College Station, TX, USA). The analysis consisted of descriptive analysis of the variables, followed by the use of Pearson's chi-squared test, with a statistical significance of 0.05 and 95% confidence interval.

Regarding the analysis of associations, multilevel modeling was used to control the cluster effect, weighted by type of school. The stepwise forward multivariate method was used, considering a statistical significance of 10% as a criterion for applying the model. The hypotheses of concomitance were tested, and variables were considered in the model according to causal plausibility.

ResultsThe sample consisted of 1402 adolescents, among whom the prevalence of bullying victims was 8.35% (95% CI: 6.75–9.94%) and perpetrators, 21.26% (95% CI: 17.84–24.39%), while the prevalence of victim-perpetrators was 2% (95% CI: 1.17–3.05%). Due to the small percentage of victim-perpetrators, it was not possible to calculate the association of this group with the studied variables.

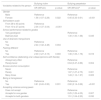

Based on the univariate analysis, the variables with p≤0.10 were selected for the multivariate analysis, as described in Table 2.

Univariate analysis of the variables related to the person associated with the occurrence of bullying, either as a victim or a perpetrator.

| Variables related to the person | Bullying victim (n=1402) | Perpetrator (n=1402) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95%CI)a | p-value | OR (95% CI)a | p-value | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | Reference | Reference | ||

| Female | 1.95 (1.34–2.84) | <0.001 | 0.41 (0.31–0.56) | 0.000 |

| Age | ||||

| From 15 to 16 years old | Reference | Reference | ||

| From 17 to 19 years old | 0.91 (0.54–1.52) | 0.715 | 1.17 (0.90–1.52) | 0.223 |

| Skin color/ethnicity | ||||

| White | Reference | Reference | ||

| Non-white | 1.30 (0.77–2.19) | 0.320 | 1.12 (0.84–1.49) | 0.428 |

| Having a physical disability | ||||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.22 (0.16–9.10) | 0.846 | 2.11 (0.48–9.16) | 0.315 |

| Sexual orientation | ||||

| Heterosexual | Reference | Reference | ||

| Bisexual/ Homosexual | 2.09 (1.21–3.62) | 0.009 | 1.39 (1.00–1.94) | 0.048 |

| Religious practice | ||||

| Yes | Reference | Reference | ||

| No | 1.04 (0.78–1.39) | 0.803 | 1.51 (1.14–1.98) | 0.003 |

| School performance related to grades | ||||

| Very good/good | Reference | Reference | ||

| Bad/very bad | 0.84 (0.56–1.24) | 0.375 | 2.03 (1.56–2.65) | <0.001 |

| Scale of self-esteem | ||||

| From 28 to 40 points | Reference | Reference | ||

| From 10 to 27 points | 2.40 (1.59–3.60) | <0.001 | 1.32 (1.05–1.67) | 0.017 |

| Feeling different | ||||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.94 (1.29–2.93) | 0.002 | 1.46 (1.13–1.89) | 0.003 |

| Self-confidence (defending one’s ideas/opinions with friends) | ||||

| Always/very often | Reference | Reference | ||

| Rarely/never | 0.90 (0.60–1.34) | 0.598 | 0.73 (0.56–0.94) | 0.016 |

| Excess alcohol consumption | ||||

| Never | Reference | – | Reference | |

| A few times | 0.80 (0.46–1.41) | 0.439 | 3.06 (2.22–4.22) | 0.000 |

| Many times | 0.97 (0.61–1.57) | 0.913 | 1.68 (1.31–2.15) | 0.000 |

| Consumption of illicit drugs | ||||

| No | Reference | – | Reference | |

| Yes | 0.63 (0.26–1.53) | 0.311 | 1.58 (1.05–2.37) | 0.026 |

| Use of medications | ||||

| To lose weight | 2.17 (1.16–4.09) | 0.015 | 1.39 (0.77–2.49) | 0.266 |

| Downers/tranquilizers | 2.81 (1.57–5.02) | <0.001 | 1.45 (1.04–2.04) | 0.028 |

| Anabolic steroids | Not calculated | – | 1.57 (0.78–3.15) | 0.199 |

| Excess weight | ||||

| No | Reference | – | Reference | |

| Yes | 1.34 (0.97–1.84) | 0.075 | 0.89 (0.67–1.18) | 0.449 |

| Being a transgressor | ||||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.75 (0.52–1.06) | 0.103 | 3.44 (2.72–4.34) | 0.000 |

| Having siblings | ||||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.48 (0.66–3.31) | 0.346 | 0.65 (0.41–1.01) | 0.057 |

| Accepts violence among peers | ||||

| Boy against boy | ||||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.69 (0.33–1.42) | 0.310 | 2.54 (1.73–3.72) | <0.001 |

| Girl against girl | ||||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.81 (0.37–1.79) | 0.605 | 2.31 (1.56–3.43) | <0.001 |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Statistical significance: p≤0.10.

After the multivariate analysis, the variable “feeling different” showed a higher risk for bullying, regardless of the role played, with females showing a value of p=0.003 and males, p=0.016. However, there was a difference according to the roles and other variables associated with bullying. Three variables were associated with the condition of being a victim: low self-esteem (p<0.001), using downers/ tranquilizers (p=0.004), and being female (p=0.022). Moreover, being a transgressor showed to be a protective factor (p=0.031). Regarding the role of being a bully, male gender (p<0.001), drinking too much alcohol a few times (p=0.001) or often (p=0.005), having poor school performance regarding grades (p=0.045), being a transgressor (p<0.001) and accepting peer violence, whether for one (p=0.007) or both genders (p=0.030), were associated with this practice. However, not defending one’s ideas (p=0.004) showed to be a protective factor for bullies (Table 3).

Multivariate analysis by multilevel modeling of factors related to the person as a bullying victim and as a perpetrator.

| Variables related to the person | Bullying victim | Bullying perpetrator | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95%CI) | p-value | OR (95%CI)a | p-value | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | Reference | Reference | ||

| Female | 1.56 (1.07–2.28) | 0.022 | 0.45 (0.33–0.61) | <0.001 |

| Self-esteem scale | ||||

| From 28 to 40 points | Reference | |||

| From 10 to 27 points | 2.04 (1.37–3.04) | <0.001 | ||

| School performance related to grades | ||||

| Very good/good | Reference | |||

| Bad/very bad | 1.30 (1.00–1.68) | 0.045 | ||

| Use of downers/ tranquilizers | ||||

| No | Reference | |||

| Yes | 2.44 (1.32–4.48) | 0.004 | ||

| Feeling different | ||||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 2.00 (1.27–3.15) | 0.003 | 1.36 (1.05–1.76) | 0.016 |

| Self-confidence (defending one’s ideas/opinions with friends) | ||||

| Always/very often | Reference | |||

| Rarely/never | 0.64 (0.47–0.86) | 0.004 | ||

| Excess alcohol consumption | ||||

| Never | Reference | |||

| Rarely | 1.87 (1.27–2.75) | 0.001 | ||

| Many times | 1.49 (1.12–1.97) | 0.005 | ||

| Being a transgressor | ||||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.61 (0.40–0.95) | 0.031 | 2.80 (2.14–3.66) | <0.001 |

| Accepting violence among peers | ||||

| Does not accept | Reference | |||

| Accepts for one gender | 2.25 (1.25–4.05) | 0.007 | ||

| Accepts for both genders | 1.51 (1.04–2.20) | 0.030 | ||

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Statistical significance: p<0.05.

This study observed a prevalence of involvement with bullying of 27.6%, with a significant difference between roles, with the role of perpetrator being more prevalent than that of victim. This fact corroborates a study carried out in Brazil with adolescents from public and private schools in Brazilian state capitals and the Federal District, which showed a prevalence of 7.2% for victims and 20.8% for perpetrators.6 This difference can be explained by the fact that often only one individual is bullied by more than one student or a group, as the victim is usually part of a minority group.

Regarding gender, a significant association was observed between being female and being bullied. A possible explanation would be the reproduction in the school environment of the cultural logic that considers women inferior to men, and because women are more physically fragile than men, they are more likely to suffer some kind of violence. In this study, differences were identified between boys and girls regarding the role played, with boys being associated with bullying as perpetrators and girls as victims. This is a situation that can be understood based on social and cultural aspects, as these conceptions attribute differences to the genders and consolidate distinct models of masculinity and femininity, considering the macho culture that encourages boys to take risks in pursuit of their socialization, self-sufficiency, and independence. Therefore, male adolescents are often expected to assume aggressive, more competitive behaviors, with a connotation of courage to affirm their social characteristics of masculinity.

Regarding the victim condition, there was also a significant association with lower levels of self-esteem and feeling different. The literature has shown that adolescents who are victims of bullying are characterized by their inhibited behavior, and tend to feel vulnerability, fear, and low self-esteem, consequently increasing the likelihood of persistent victimization.19 Moreover, adolescents with low self-esteem tend to develop mechanisms that distort their thoughts and feelings, leading them to lack faith in themselves,20 therefore justifying the presence of such feelings in the assessed students.

Other relevant data refer to the fact that when adolescents did not defend their personal ideas and opinions among their friends, it constituted a protective factor for bullying, while playing the role of perpetrator showed a higher probability of defending one’s ideas and opinions. This result favors the concept that the perpetrators are more self-confident and can impose their judgments and values on others as they wish, possibly to the point of promoting the involvement of other adolescents with this bullying practice, being considered a leader.

Another aspect to be highlighted is the association of poor school performance with adolescent perpetrators, which raises some hypotheses. The first is related to the possibility that the existing difficulties in performing school activities expose their weaknesses, thus these students seek to show their superiority and importance through their aggressive behavior, in an attempt to be respected by their peers.4 Another possibility would be that involvement in bullying in the role of perpetrator, and as a result the frequent search for recognition and power, become a priority in the school environment, thus interfering with school activities and, consequently, reflecting on their school performance.

Regarding the association between using downers/tranquilizers and being a victim, it only ratifies the observed facts about the profile of those involved, who show low self-esteem and feel different to the point of using substances, aiming at altering their feelings and sensations, to resolve the issues in a more immediate way.

Also on this subject, it is important to consider not only the possible complications resulting from the prolonged use of tranquilizers, but also to reflect on how easy it is for the adolescent population to get access to medications that should be partially or totally controlled by the health authorities, a fact already discussed in a study carried out by Muza et al.21

Regarding alcohol consumption, being a perpetrator was associated with the use of this substance.22,23 This is a matter of concern, since alcohol consumption has been starting among adolescents at an increasingly earlier age, and frequently among high school students in South America, and it is associated with peer violence.24,25

Another fact that deserves attention is related to students who exhibit transgressive behavior associated with bullying, as studies have shown that these individuals are more likely to develop criminal behavior or to be criminally convicted in adulthood,26 as well as to have relationship and psychotic problems.27 At the same time, being a victim is a protective factor against such behavior.

Corroborating this information, studies have shown that the involvement of adolescents with violence is due to several factors, including adolescence itself, substance abuse, family conflicts and violence, exposure to violence, and situations of violence or marital conflict, which may induce violent behaviors by adolescents.28,29

The significant association of students who practice bullying with the variable “acceptance of peer violence” is noteworthy, as it is a matter of concern to consider the aggression suffered or committed by a peer of same or opposing gender as a natural occurrence.

However, such naturalization may be related to situations of violence due to parents or other family members experienced during one’s life.30 Moreover, the literature reinforces that different types of mistreatment experienced during childhood are considered risk factors for the occurrence of interpersonal violence in adolescence.30

It is worth noting that the current study has some limitations that refer to the fact that all provided data were collected from those self-reported by the students, so it allows different interpretations about bullying and other variables, minimized by the use of an adapted tool validated for the population. Moreover, this is a cross-sectional study, which offers a precise perception of reality and does not allow establishing a cause-and-effect relationship. Thus, longitudinal and/or qualitative studies with the same variables are suggested, in order to establish causal relationships.

The data showed the involvement of adolescents with bullying, with the condition of perpetrator being more prevalent. However, the difference between victims and perpetrators considering their personal characteristics is noteworthy.

The results show that the profile of bullying perpetrator found in this study is associated with the male gender, excessive alcohol consumption, practice of illicit behaviors, and acceptance of peer violence. These are important data for developing and planning practices against bullying.

Based on the risk factors found for both the role of victim and perpetrator, schools should be concerned about providing greater support and supervision to these adolescents, encouraging group discussions about ethics and respect for differences, as well as developing activities that encourage solidarity among classmates. However, the difference in the role played in bullying should be discussed in all environments, especially in family and school settings.

The present study allows, through a more integrative view, a better understanding of those involved in bullying, pointing out the need for effective actions that consider the personal factors related to the role played (victim and perpetrator).

FundingThis study was funded by PAPES VI/FIOCRUZ/CNPq (process 407738/2012.6).

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Silva GR, Lima ML, Barreira AK, Acioli RM. Prevalence and factors associated with bullying: differences between the roles of bullies and victims of bullying. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2020;96:694–702.