To identify prenatal, perinatal and postnatal risk factors in children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) by comparing them to their siblings without autistic disorders.

MethodThe present study is cross sectional and comparative. It was conducted over a period of three months (July–September 2014). It included 101 children: 50 ASD's children diagnosed according to DSM-5 criteria and 51 unaffected siblings. The severity of ASD was assessed by the CARS.

ResultsOur study revealed a higher prevalence of prenatal, perinatal and postnatal factors in children with ASD in comparison with unaffected siblings. It showed also a significant association between perinatal and postnatal factors and ASD (respectively p=0.03 and p=0.042). In this group, perinatal factors were mainly as type of suffering acute fetal (26% of cases), long duration of delivery and prematurity (18% of cases for each factor), while postnatal factors were represented principally by respiratory infections (24%). As for parental factors, no correlation was found between advanced age of parents at the moment of the conception and ASD. Likewise, no correlation was observed between the severity of ASD and different factors. After logistic regression, the risk factors retained for autism in the final model were: male gender, prenatal urinary tract infection, acute fetal distress, difficult labor and respiratory infection.

ConclusionsThe present survey confirms the high prevalence of prenatal, perinatal and postnatal factors in children with ASD and suggests the intervention of some of these factors (acute fetal distress and difficult labor, among others), as determinant variables for the genesis of ASD.

Identificar fatores de risco pré-natal, perinatal e pós-natal em crianças com transtorno do espectro do autismo (TEA) ao compará-las a irmãos sem transtornos de autismo.

MétodoEste estudo é transversal e comparativo. Ele foi conduzido em um período de três meses (julho a setembro de 2014). Incluiu 101 crianças: 50 crianças com TEAs diagnosticadas de acordo com os critérios do DSM-5 e 51 irmãos não afetados. A gravidade do TEA foi avaliada pela Escala de Avaliação do Autismo na Infância (CARS).

ResultadosNosso estudo revelou uma prevalência maior de fatores pré-natais, perinatais e pós-natais em crianças com TEA em comparação a irmãos não afetados. Também mostrou uma associação significativa entre fatores perinatais e pós-natais e TEA (respectivamente p=0,03 e p=0,042). Nesse grupo, os fatores perinatais foram principalmente do tipo sofrimento fetal agudo (26% dos casos), longa duração do parto e prematuridade (18% dos casos em cada fator), ao passo que fatores pós-natais foram representados principalmente por infecções respiratórias (24%). No que diz respeito a fatores dos pais, nenhuma correlação foi encontrada entre a idade avançada dos pais no momento da concepção e o TEA. Da mesma forma, nenhuma correlação foi estabelecida entre a gravidade do TEA e fatores diferentes.

Após regressão logística, os fatores de risco de autismo encontrados no modelo final foram: sexo masculino, infecção pré-natal do trato urinário, sofrimento fetal agudo, parto difícil e infecção respiratória.

ConclusõesEsta pesquisa confirma a alta prevalência de fatores pré-natais, perinatais e pós-natais em crianças com TEA e sugere a intervenção de alguns desses fatores (sofrimento fetal agudo, parto difícil…) como variáveis determinantes para a gênese do TEA.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a complex neurodevelopmental condition. Based on the 5th edition of Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), specific diagnostic criteria for childhood autism include social skills and communication deficit associated with restrictive and repetitive behaviors, interests, or activities.1 ASD is currently one of the most common childhood morbidities, presenting in various degrees of severity. The most recent global prevalence of autism was estimated at 0.62%.2

This disorder has grown into a constant challenge for many countries such as Tunisia, as it has a severe impact on both the affected individuals and their families. The financial burden, which has become more acute since the Tunisian revolution, along with the lack of scientific knowledge about the epidemiology, etiology, and natural course of this condition, have rendered the situation more complex.3–5

The spectrum of symptoms and the extreme complexity in the developmental and associated medical conditions within ASD do not necessarily mean a single etiology. Several hypotheses concerning the pathogenesis have been proposed, including the interaction of environmental factors and various genetic predispositions.5,6 Studies based on concordance rates among monozygotic twins and families suggest a possible role of both genetic and environmental factors in the etiology of ASD.7

A recent study suggests that genetic factors account for only 35–40% of the contributing elements.8,9 The remaining 60–65% are likely due to other factors, such as prenatal, perinatal, and postnatal environmental factors. Since ASDs are neurodevelopmental disorders, neonatally-observed complications that are markers of events or processes that emerge early during the perinatal period may be particularly important to consider.8

To the best of our knowledge, in Tunisia, there are no studies that have considered the relationship between prenatal, perinatal, and postnatal risk factors and ASD.

Thus, the aim of the present study was to identify the pre-, peri-, and postnatal factors associated to ASD by comparing children with ASD to their siblings who do not present any autistic disorders.

MethodsStudyThis was a cross sectional and comparative study. It was conducted over a period of three months from July to September 2014.

PopulationParticipantsThe sample included 101 children divided into two groups:

- 1.

The first group was composed of 50 autistic children previously identified and followed regularly in the child and adolescent psychiatry department of the Hedi CHAKER Hospital of Sfax (Tunisia). These patients came from different regions of Tunisia, as there are only three child psychiatry departments in the entire country. Subject ages ranged between 3 and 7 years.

- 2.

The second group was composed of 51 non-autistic children, aged between 3 and 12 years.

- -

For the first group, the study included children who both met the DSM-5 criteria for ASD and whose score at the Child Autistic Rating Scale (CARS) was ≥30.

- -

For the second group, the unaffected siblings were included as controls.

In both groups, the children were aged at least 3 years. This criterion for age selection is based on the fact that ASD is identified with a high degree of certainty at the age of 3.

Exclusion criteriaExclusion criteria: known neurogenetic conditions (e.g., tuberous sclerosis, neurofibromatosis, fragile X syndrome, Down syndrome).

The control group shared the same exclusion criteria.

ToolsDSM-5 diagnostic criteria for ASDIn DSM-5, ASD encompasses the previous DSM-IV autistic disorder (autism), Asperger's disorder, childhood disintegrative disorder, and pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified.1

CARSCARS assesses the intensity of ASD symptomatology. It evaluates the severity of autistic behaviors in 14 functional areas by assigning a score from 1 to 4. An overall score is calculated by adding all the grades, to stratify patients into three levels: “severely autistic” (score between 37 and 60), “mildly to moderately autistic” (score between 30 and 36.5), and “absence of ASD” (score less than 30).10 The time for administering this questionnaire is around 20–30min.

ProceduresAll study procedures were approved by the local Research Ethics Committee.

Informal consent from parents or legal guardians of participants was obtained after the nature of the procedures had been fully explained.

The interviews were conducted with mothers in 78% of the cases, with fathers in 4% of the cases, and with both parents in 18% of the cases, by a properly trained child psychiatrist.

Parents completed a medical history questionnaire with a combination of closed and open-ended questions regarding pregnancy, labor, and complications during and after birth. Additionally, data were collected with reference to medical record and medical birth book.

The studied variables were designed according to the probable risk factors of ASD from existing literature. The following variables, which were considered for both groups, were classified as parental factors, pre-, peri-, and postnatal characteristics and were codified as binary variables (yes/no).

Parental factors: Advanced maternal and paternal age at the time of childbirth (≥35 years), consanguinity.

Prenatal factors: These consisted of conditions that arose during pregnancy, such as gestational diabetes, which usually develops in the second half of pregnancy; high and low blood pressure; gestational infections; and fetal distress inducing threatened abortion conditions, such as amniotic fluid loss, bleeding during gestation, and suboptimal intrauterine conditions. Perinatal factors: delivery characteristics, such as term birth (premature or post-term birth); delivery types, including forceps or cesarean section; acute fetal distress; and birth weight (low birth weight [<2500g] and macrosomia [>4000g])

Postnatal factors: All conditions occurring in the first six weeks after birth, such as respiratory and urinary infections; auditory deficit (a loss of 30dB); and blood disorders such as anemia and thrombopenia.

The diagnosis of respiratory and urinary infections was achieved during hospitalizations in pediatric services.

Statistical analysisStatistical analysis was done using SPSS software for Windows, release 20.0 (IBM Corp. Released 2011. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 20.0, USA). The analysis included a descriptive study, observing the frequencies for the quantitative variables and means and standard deviations for the qualitative variables, as well as an analytical study, using Pearson's correlation coefficient to establish correlations between the two groups. The level of statistical significance was set at p<0.05 (alpha level of 5%).

In the multivariable analysis, logistic regression was performed to identify risk factors for autism, taking into account confounding factors and using the down method of Wald.

Initially, all the variables significantly associated with autism were included in the univariable analysis, as well as those found as risk factors in the literature. The significance level was set at 20%. The final model accuracy was verified and calculated according to the Hosmer and Lemeshow test. The results were expressed by the adjusted odds ratio (ORa) with their confidence intervals, 95% CI (ORa).

ResultsClinical profile of children with ASDThis study included 50 children. A male predominance (37 boys and 13 girls) was observed, as well as a moderate socioeconomic level in 90% of cases, and a predominance of the mild to moderate form of ASD at the CARS (62% vs. 38% for the severe form).

Parental factorsTable 1 shows the distribution of parental age at the moment of conception in both groups. It indicates that the rate of advanced age (≥35 years) among parents at the moment of conception was higher in children with ASD than in their siblings (66% vs. 49.01% for fathers and 24% vs. 19.6% for mothers), but the difference was statistically non-significant.

In the present study, the rate of consanguinity was 28% (first degree in 31% of cases, second degree in 26% of cases, and third degree in 43% of cases).

Prenatal, perinatal, and postnatal factors (Table 2)Table 2 displays a comparison of prenatal, perinatal, and postnatal factors between both groups. Despite the fact that no statistically significant differences were observed between prenatal factors in the groups (p=0.13), the prevalence was higher in the first group (50% vs. 35.3%). Table 2 shows that perinatal factors were more frequent in the first group, with a rate of 60% vs. 11.8% in the second group, a statistically significant difference (p=0.03). The most frequent perinatal factors found in the ASD group were acute fetal distress (26%), prematurity, and difficult labor observed in 18% in each case.

Correlation between pre-, peri-, and postnatal factors in both groups.

| Group 1 (n=50) | Group 2 (n=51) | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Prenatal factors | 25 | 50 | 18 | 35.3 | 0.13 |

| Exposure to cigarette smoking | 11 | 22 | 6 | 11.8 | 0.16 |

| Urinary infection | 6 | 12 | 2 | 3.9 | 0.16 |

| Hypertension in pregnancy | 5 | 10 | 3 | 5.9 | 0.48 |

| Threatened abortion | 5 | 10 | 3 | 5.9 | 0.48 |

| Gestational diabetes | 4 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 0.2 |

| Hypotension | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0.49 |

| Perinatal factors | 30 | 60 | 6 | 11.8 | <0.01 |

| Acute fetal distress | 13 | 26 | 3 | 5.9 | 0.006 |

| Prematurity | 9 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 0.001 |

| Exceeding the term | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Difficult labor | 9 | 18 | 3 | 5.9 | 0.06 |

| Low birth weighta | 6 | 12 | 1 | 2 | 0.06 |

| Macrosomiab | 3 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 0.36 |

| Postnatal factors | 20 | 40 | 5 | 9.8 | <0.01 |

| Respiratory infection | 12 | 24 | 1 | 2 | 0.001 |

| Urinary infection | 3 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 0.36 |

| Auditory deficitc | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0.24 |

| Blood diseased | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3.9 | 1 |

As for postnatal factors, they were associated with ASD (40% in the first group vs. 9.8% in the second group, p=0.042); these postnatal factors were primarily a type of respiratory infection (24% of the cases in the first group).

Table 3 shows that after logistic regression, the risk factors for autism that remained in the final model were: male gender, prenatal urinary tract infection, acute fetal distress, difficult labor, and respiratory infection.

Adjusted analysis of risk factors of ASD.

| Covariates | Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | p-Value | ORa | 95% CI (ORa) | p-Value | |

| Gender | 2.15 | 0.07 | 2.5 | [0.9–6.9] | 0.07 |

| Exposure to cigarette smoking | 2.11 | 0.16 | – | – | – |

| Urinary infection | 3.34 | 0.16 | 5.7 | [0.8–38.2] | 0.07 |

| Gestational diabetes | 4.34 | 0.2 | – | – | – |

| Acute fetal distress | 5.6 | 0.006 | 5.2 | [1.2–21.6] | 0.02 |

| Prematurity | 0.001 | – | – | – | |

| Difficult labor | 3.51 | 0.06 | 3.6 | [0.8–16] | 0.09 |

| Low birth weight | 6.8 | 0.06 | – | – | – |

| Respiratory infection | 15.7 | 0.001 | 22.2 | [2.5–191.03] | 0.005 |

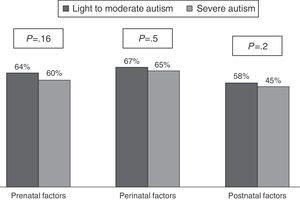

Fig. 1 shows the distribution of prenatal, perinatal, and postnatal factors according to the severity of autism.

No association was observed between the severity of autism and the prenatal, perinatal, and postnatal factors.

DiscussionThe present study discusses prenatal, perinatal, and postnatal complications, as well as some parental characteristics, that could be considered as risk factors for ASD.

Parental factorsPrevious studies have linked advanced maternal and paternal age to increased risk for ASDs.11,12

In the present study, the chose 35 years as the age cut-off for both parents. This choice was based the recommendations of many authors.11–13 Despite the fact that a correlation between advanced age at the moment of the conception of both parents and ASD was not observed, the frequency of parents aged over 35 years was higher in children with ASD than their siblings (respectively 24% vs. 19.6% for maternal age and two-thirds vs. almost 50% for paternal age).

Theories advocating the association between parental age and increased risk for ASDs include the potential for more genetic mutations in the gametes of older fathers and mothers, as well as a less favorable in utero environment in older mothers, with more obstetrical complications such as low birth weight, prematurity, and cerebral hypoxia.11

Moreover, according to some studies, high prevalence of chronic diseases among older women could contribute to expand the risk of adverse birth outcomes.12,14 Data from the literature trying to explain the increased risk for ASD's among older mothers have incriminated the high risk of obstetric complications observed in these mothers.11,12,14

Furthermore, congenital anomalies are also more common in the fetuses and infants of older mothers, and these conditions contribute in increasing the risk of ASD.

In the present study, a rate of 28% of consanguinity was observed. In the literature, it is stated that consanguinity increases the chances of inheriting a bad DNA fit, which will definitely result in a birth defect. Inbred disorders may cause other abnormalities, and ASD can also be brought on by other conditions.15 Since the control group, in the present study, was represented by the siblings conceived and born from the same biological parents, consanguinity could not be evaluated as a risk factor for ASD.

Prenatal, perinatal and postnatal factorsIn the present survey, no correlation was observed between the severity of ASD and prenatal, perinatal, and postnatal factors. The present results are in agreement with some recent studies.16,17 Conversely, some hypothesis have been raised, indicating that the light form of autism would show weaker or no association with obstetric risk factors.

Prenatal factorsIn the present study, the occurrence of maternal infection was higher among cases when compared to controls (12% for the first group vs. 3.9% for controls).

According to many studies, adverse intrauterine environment resulting from maternal bacterial and viral infections during pregnancy is a significant risk factor for several neuropsychiatric disorders including ASD.15 The association between intrauterine inflammation, infection, and ASD is based on both epidemiological studies and case reports. This association is apparently related to maternal inflammatory process; hence, maternal immune activation may play a role in neuro-developmental perturbation.

In large population studies, researchers have not identified a specific infection, but rather an increased rate of ASD, especially when the maternal infection is rather severe and requires hospitalization.15,18

Among the prenatal factors identified in this study, exposure to cigarette tobacco (passive smoking) was noted in 22% of cases. Retrospective epidemiological studies have observed, among mothers of children with ASD, a significantly increased percentage of women who were exposed to tobacco during the conception of the child. Therefore, maternal smoking was considered as a potential maternal confounding factor, as well as other toxic chemicals.6

Some authors have demonstrated that maternal cigarette smoking during pregnancy may have a commutative impact on the lineage of her reproductive cells; it is also associated with an increased rate of spontaneous abortions, preterm delivery, reduced birth weight, among others.19 The findings regarding its relation with ASD are still controversial.20–22

The present study showed that the frequency of gestational diabetes was higher in the first group (8% vs. 2% in the second group).

According to some authors, gestational diabetes is mainly associated with disturbed fetal growth and increased rate of a variety of pregnancy complications.23 It also affects fine and gross motor development and increases the rate of learning difficulties and of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, a common comorbid neurobehavioral problem in ASD. The negative effects of maternal diabetes on the brain may result from intrauterine increased fetal oxidative stress and epigenetic changes in the expression of several genes. The increased risk observed might be related to other pregnancy complications that are common in diabetes, or to effects on fetal growth rather than to complications of hyperglycemia. It is also unknown whether optimal control of diabetes will further decrease this association.23

Because of its rising incidence, maternal diabetes has been considered, by several studies, as an obvious candidate to be associated with ASD, whereas others have failed to demonstrate such associations.15,20,23

In the current survey, hypertension, hypotension, and threatened abortion were more frequent in the first group (respectively 10% vs. 5.9%, 2% vs. 0%, and 10% vs. 5.9% in the second group). These conditions are generally related to fetal loss and adverse infant outcomes, such as prematurity, intrauterine growth retardation, still birth, and neonatal death indicating fetal distress. Likewise, fetal hypoxia is one of the manifestations of fetal distress and has been reported to induce conditions such as placental abruption, threatened premature delivery, emergency cesarean section, forceps delivery, spontaneous abortion, and varying degrees of cerebral damage.4,5 Accordingly, ASD was linked to fetal distress: oxygen deprivation could damage vulnerable regions in the brain, such as the basal ganglia, hippocampus, and lateral ventricles. Some neuroimaging studies have demonstrated abnormalities in these regions among patients with ASD compared with controls.5,14

Perinatal factorsIn the present series, perinatal factors were very significantly associated with ASD (p=0.03). This result is consistent with the literature.4,24 In fact, complications occurring during labor affect the neurodevelopment of the fetus and infant in later stages, and can contribute toward the risk of ASD.

The current research also suggests that obstetric factors occur more frequently in ASD children than in their unaffected siblings. The present results corroborate other studies reporting an association between perinatal factors and ASD.

Perinatal factors were represented by a long duration of delivery and prematurity in 18% of the cases each one and suffering acute fetal in 26% of the cases. Therefore, it is admitted that these conditions may lead to fetal distress and asphyxia, resulting in brain damage. Fetal oxygen deprivation has been proposed to increase the risk for ASD. Recently, research has highlighted the occurrence of ASDs in very preterm infants, in addition to already identified developmental disorders.4,14,24

Postnatal factorsThe present findings are in agreement with previous studies suggesting that postnatal events may increase the risk for ASDs in some children.4 In fact, a significant association between postnatal factors and ASD (p=0.042) has been observed.

In the present study, an association was observed between both urinary and respiratory infections and ASD. These findings could be explained by the release of cytokines as immune responses of the baby to these infections, which can affect neural cell proliferation and differentiation. These impairments are known to be associated with ASD.5,25

Hearing deficits were more common in the first group (4% vs. 0% in the second group). The present results corroborate those of Fombonne,26 who reported, in a meta-analysis, that the prevalence of sensory deficits in autism vary from 0.9% to 5.9%.

Rosenhall et al.,27 in a study conducted on 199 children and adolescents with ASD, estimated that the prevalence of hearing impairment in autism is ten times higher than in general population (11%). They also observed that 7.9% of the patients had an moderate hearing loss, 3.5% were profoundly deaf, and 18% had hyperacusis in the audiogram, even after controlling for the age factor. More recently, Kielinen et al.28 observed, in a population of children with autism, that 8.6% had a mild hearing loss, 7% a moderate deficit, and 1.6% severe deficiency (hearing loss in more than 60dB at audiometry).

The strength of the present study lies in its precise confirmation of the ASD, the active participation of parents, and resorting to unaffected siblings as controls. This last feature may help to identify risk factors and to control for hereditary background, family environment, and maternal predisposition to complications in pregnancy or birth. Nonetheless, there are some limitations, namely the limited number of samples. Therefore, the present results should be completed by epidemiological studies with a larger scale and in larger populations. To face the issue of ASD and consanguinity, a larger population with and without consanguinity should be evaluated.

In the present study, no individual factor in the prenatal period was consistently significant as a risk factor for ASD. In the literature, some of these factors were associated with autism; therefore, they should be considered as potential risk factors, as well as perinatal and postnatal events.

Prenatal, perinatal, and postnatal factors for ASD should be considered in the broadest sense: these events of the fetal, newborn, and infant environment could interact or contribute in combination with other co-factors (environmental and genetic, among others) to characterize ASD. Scores indicate that rather than focusing on a single factor, future studies should investigate the combination of several factors.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Hadjkacem I, Ayadi H, Turki M, Yaich S, Khemekhem K, Walha A, et al. Prenatal, perinatal and postnatal factors associated with autism spectrum disorder. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2016;92:595–601.