To organize the main findings and list the most frequent recommendations from systematic reviews of interventions developed at the school environment aimed at reducing overweight in children and adolescents.

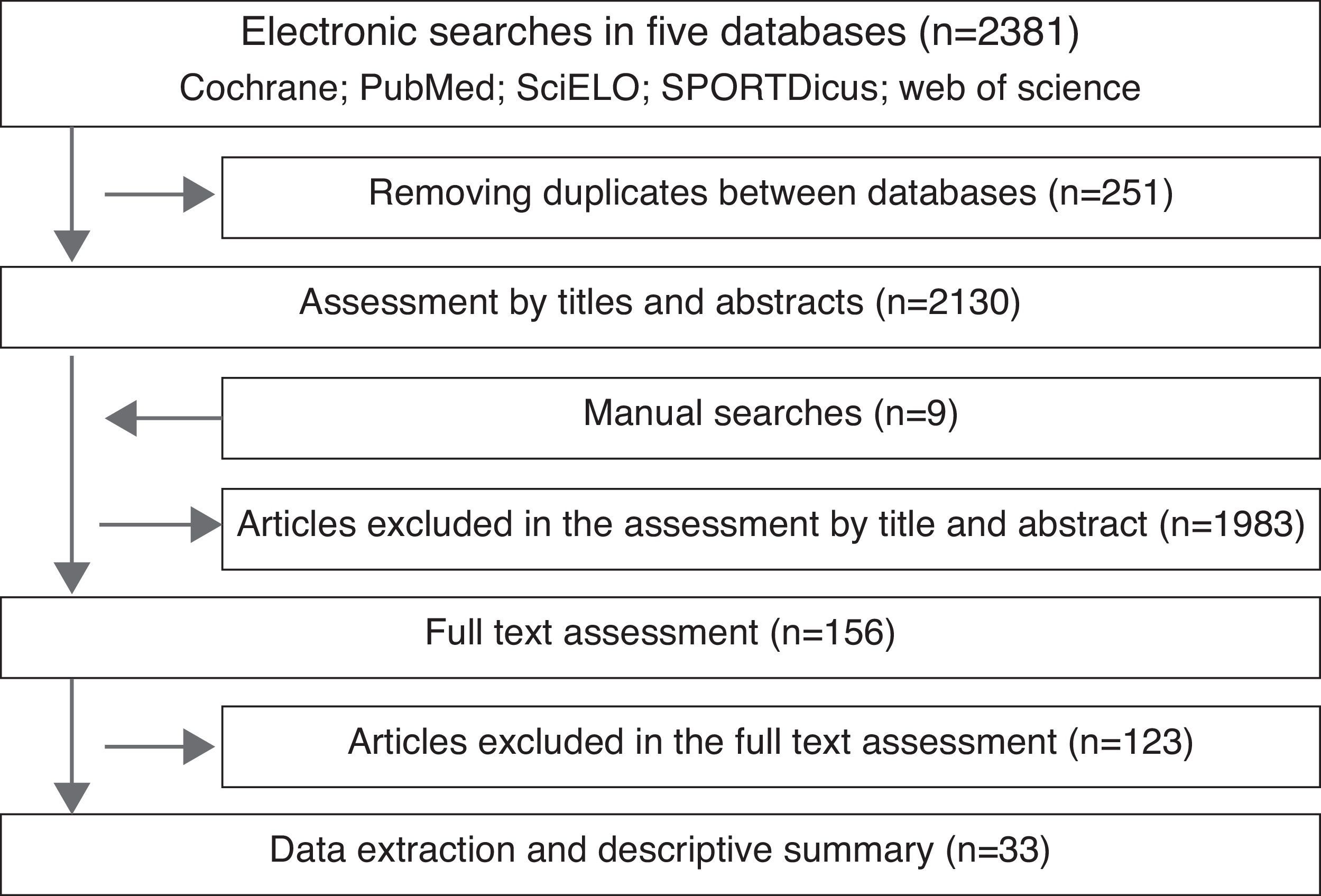

Data sourceSearches for systematic reviews available until December 31, 2014 were conducted in five electronic databases: Cochrane, PubMed, SciELO, SPORTDiscus, and Web of Science. Manual search for cross-references were also performed.

Summary of the findingsOf the initial 2139 references, 33 systematic reviews adequately met the inclusion criteria and were included in the descriptive summary. In this set, interventions with periods of time greater than six months in duration (nine reviews), and parental involvement in the content and/or planned actions (six reviews) were identified as the most frequent and effective recommendations. Additionally, it was observed that boys respond more effectively to structural interventions, whereas girls respond to behavioral interventions. None of the included reviews was able to make inferences about the theoretical basis used in interventions as, apparently, those in charge of the interventions disregarded this component in their preparation.

ConclusionsAlthough the summary identified evidence with important applications in terms of public health, there are still gaps to be filled in this field of knowledge, such as the effectiveness of different theoretical models, the identification of the best strategies in relation to gender and age of participants and, finally, the identification of moderating variables to maximize the benefits provided by the interventions.

Organizar os principais achados e elencar as recomendações mais frequentes das revisões sistemáticas de intervenções desenvolvidas no ambiente escolar com fins na redução do excesso de peso em crianças e adolescentes.

Fonte dos dadosBuscas por revisões sistemáticas disponíveis até 31 de Dezembro de 2014 foram realizadas em cinco bases de dados eletrônicas: Cochrane, PubMed, SciELO, SPORTDiscus, e Web of Science. Buscas manuais por referências cruzadas também foram desenvolvidas.

Síntese dos dadosDas 2.139 referências iniciais, 33 revisões sistemáticas responderam adequadamente aos critérios de inclusão e compuseram a síntese descritiva. Neste conjunto, identificou-se como recomendações mais frequentes e efetivas intervenções que possuem períodos de tempo superior a seis meses de duração (9 revisões), e o envolvimento dos pais nos conteúdos e/ou ações previstas (6 revisões). Além disso, observou-se que meninos respondem de forma mais efetivas as intervenções estruturais enquanto as meninas às intervenções comportamentais. De modo consistente entre as revisões incluídas, nenhuma delas conseguiu realizar inferências sobre a base teórica utilizada nas intervenções, uma vez que, aparentemente, os responsáveis pelas intervenções desconsideraram esse componente em sua elaboração.

ConclusõesEmbora a síntese tenha identificado evidências com aplicações importantes em termos de saúde coletiva, ainda existem lacunas a serem preenchidas nesse campo do conhecimento, tais como a efetividade de diferentes modelos teóricos, o reconhecimento das melhores estratégias em relação ao sexo e a idade dos participantes e, por fim, a identificação de variáveis moderadoras para potencializar os benefícios proporcionado pelas intervenções.

In children and adolescents, the high prevalence of overweight observed in different parts of the world1 has reinforced the need to implement new preventive strategies, highlighting the important role of physical activity (PA) and nutrition education (NE).2

Researchers and health professionals agree on the school's potential as a favorable place for the development of interventions that involve practices and contents in PA and/or NE, considering some advantages offered by this environment, for instance, the scope of actions; the large number of students receiving the same stimulus at the same time; the continuity of the strategies over time, due to the permanence of children and/or adolescents in schools; and the possibility of both structural and operational changes.2–4

As a result of this consensus, the scientific literature has received reports of a large number of interventions developed in the school environment with the purpose of preventing and/or reducing child obesity after the early 2000s,5 which favored the development of the first systematic reviews on the subject.6–8 However, apart from the associated goals, it is noteworthy that these reviews have conflicting and inconclusive results, mostly due to the great variability of the methods employed in the original publications (e.g., theoretical basis, time of duration, actions developed), as well as due to the type and number of assessed studies.5,9

Aiming to correct these uncertainties, other systematic reviews were conducted, seeking to provide plausible explanations for the high variability among the original results,10–12 increasing the number of correlated reviews with discordant results, which probably has limited their acceptance in practice, as well as their implementation as public policy. Conversely, while the debate on the inconclusive results of these reviews was expanded, the confirmation of the common evidence of these reviews was relegated to the background. In practical terms, for school professionals, these evidence could guide the design and implementation of new interventions, aimed at preventing childhood overweight.

By retrieving correlated systematic reviews, this study aimed to organize the main findings and list the most frequent recommendations from systematic reviews of interventions developed at the school environment with the purpose of reducing overweight in children and adolescents.

MethodsEligibility criteriaFor the summary composition, the authors sought systematic reviews of intervention studies whose strategies were developed in the school environment, aiming at preventing and/or reducing overweight in children and/or adolescents. Interventions could include theoretical and/or practical contents of PA and/or NE.

Narrative reviews, essays, overviews, and meta-analyses were not included. Specifically, the non-inclusion of meta-analyses aimed to improve the comparability between the results of systematic reviews, which have a more descriptive approach. Reviews published in oriental languages were not included either, due to the difficulty of access and translation.

Search strategiesTwo strategies were used for retrieving references of interest: (i) systematic searches in five electronic databases (Cochrane, PubMed, SciELO, SPORTDiscus, Web of Science), using a previous referential model adapted to each database5: (school) AND (physical activity) OR (physical education) OR (exercise) OR (physical fitness) OR (sports) OR (nutrition) OR (nutritional science) OR (child nutrition sciences) OR (nutrition education) OR (diet) OR (energy intake) OR (energy density) OR (calories) OR (calorie) OR (food) OR (fruit) OR (vegetable)) AND ((weight) OR (obese) OR (overweight) OR (weight reduction) OR (anthropometric) OR (anthropometry) OR (nutritional status) OR (nutrition assessment) OR (body mass index) OR (BMI) OR (body weights and measures) OR (waist circumference) OR (adipose tissue)) AND review or overview or meta-analysis or metanalysis and (ii) manual searches for references in the individual collections of articles by each author, as well as by identifying cross-references. This research included studies published until December 31, 2014.

Selection, extraction and synthesis of dataOne reviewer (PG) processed the data in three phases: (i) conference and removal of duplicates among the databases; (ii) title and abstract reading, where all works characterized as reviews were included; (iii) data extraction and preparation of the descriptive summary.

ResultsThe electronic and manual searches retrieved 2139 relevant references, which were evaluated by their titles and abstracts. After this phase, 156 remained and were evaluated regarding the full text; among these, only 33 reviews adequately met the eligibility criteria, and were then used to constitute the descriptive summary (Fig. 1).6–8,10–39

Among the papers included in this systematic reviews, 25 assessed the effectiveness of interventions conducted at schools aiming at obesity prevention and/or control.6–8,10–12,14–18,20,23,24,27,30–39 Even though many of the reviews recovered data from different anthropometric measures in their respective summaries, most of the interventions sought changes in body mass index. In four publications, obesity was verified as a secondary outcome (Table 1).19,21,22,28 Regarding the geographical aspect, eight reviews restricted their goals to interventions developed in specific countries or continents, such as Latin America, Canada, China, United States, Europe, and the United Kingdom.8,10,12,18,28,29,32,36 Conversely, other reviews sought to assess the role of interventions in specific groups, such as those developed in populations with overweight,39 low socioeconomic status,33,35 and specific ethnicities, such as the publication that aimed to determine the effects of interventions directed to children of Hispanic origin living in the USA.38

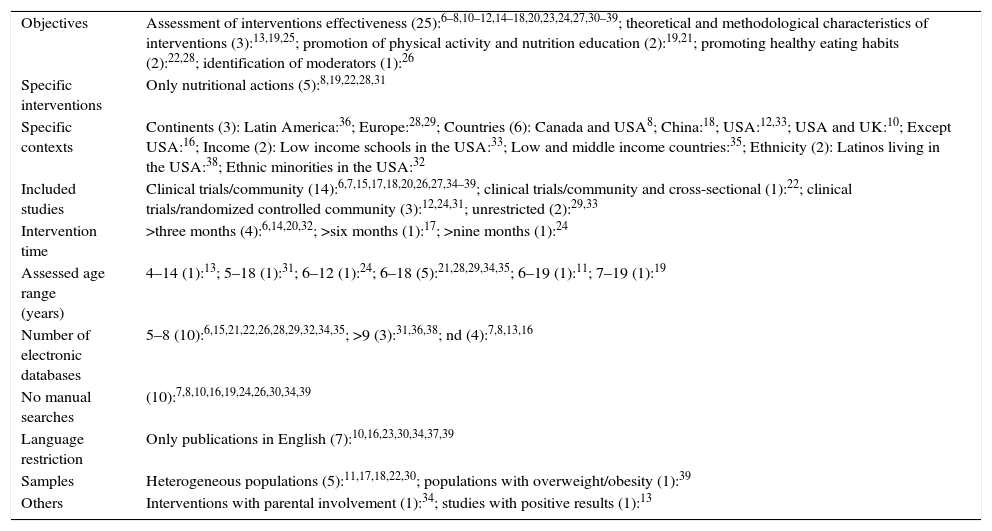

Methodological characteristics of the included systematic reviews (n=33).

| Objectives | Assessment of interventions effectiveness (25):6–8,10–12,14–18,20,23,24,27,30–39; theoretical and methodological characteristics of interventions (3):13,19,25; promotion of physical activity and nutrition education (2):19,21; promoting healthy eating habits (2):22,28; identification of moderators (1):26 |

| Specific interventions | Only nutritional actions (5):8,19,22,28,31 |

| Specific contexts | Continents (3): Latin America:36; Europe:28,29; Countries (6): Canada and USA8; China:18; USA:12,33; USA and UK:10; Except USA:16; Income (2): Low income schools in the USA:33; Low and middle income countries:35; Ethnicity (2): Latinos living in the USA:38; Ethnic minorities in the USA:32 |

| Included studies | Clinical trials/community (14):6,7,15,17,18,20,26,27,34–39; clinical trials/community and cross-sectional (1):22; clinical trials/randomized controlled community (3):12,24,31; unrestricted (2):29,33 |

| Intervention time | >three months (4):6,14,20,32; >six months (1):17; >nine months (1):24 |

| Assessed age range (years) | 4–14 (1):13; 5–18 (1):31; 6–12 (1):24; 6–18 (5):21,28,29,34,35; 6–19 (1):11; 7–19 (1):19 |

| Number of electronic databases | 5–8 (10):6,15,21,22,26,28,29,32,34,35; >9 (3):31,36,38; nd (4):7,8,13,16 |

| No manual searches | (10):7,8,10,16,19,24,26,30,34,39 |

| Language restriction | Only publications in English (7):10,16,23,30,34,37,39 |

| Samples | Heterogeneous populations (5):11,17,18,22,30; populations with overweight/obesity (1):39 |

| Others | Interventions with parental involvement (1):34; studies with positive results (1):13 |

Table 1 also shows that six reviews established cut-off points for the duration of the interventions, seeking strategies that were developed for minimum periods of three,6,14,20,32 six,17 and nine months.24 Eight reviews sought original articles specifically reported in English.10,16,23,25,30,34,37,39 However, it is noteworthy that only one of these reviews focused specifically on studies conducted in countries whose official language is English, i.e., the United Kingdom and United States.10 Additionally, there was a high heterogeneity concerning the search methods in the scientific literature in relation to the number of searched databases (ranging from one to 14), use of manual searches (n=23), and year of publication (23 used articles published after 1990).

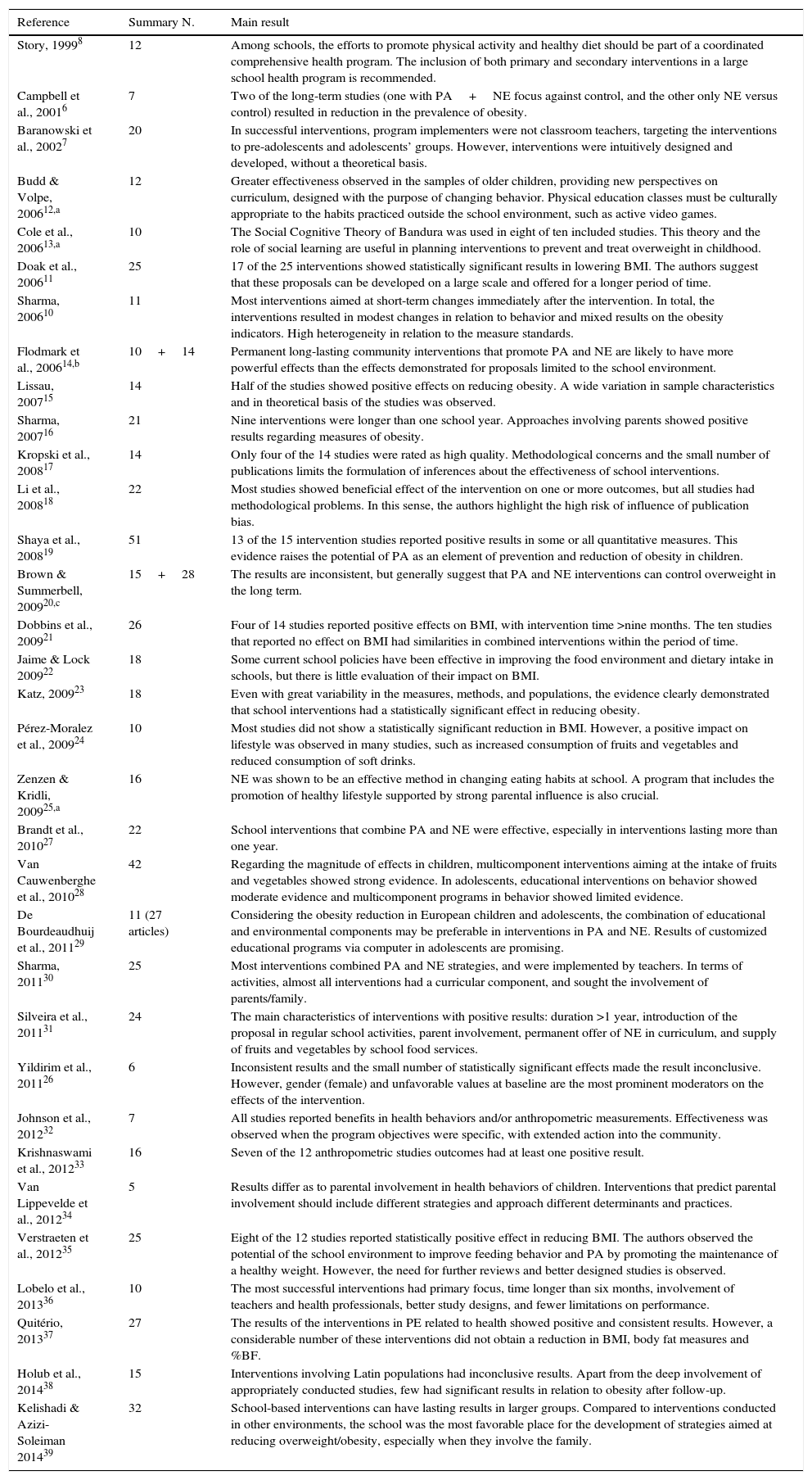

Table 2 shows that the oldest systematic review in this summary was published in 1999.8 However, an increase in the frequency of reviews published from 2006 onwards (n=30; 91.8%) was observed10–39; 2009 was the year with the highest number of publications (n=6; 21.1%).20–25 Also, it was observed that, after 2006, at least two correlated systematic reviews were published annually. As a consequence of the different methodological options, the selected reviews showed great variability in the number of included articles, with a minimum of five34 and maximum of 51 original studies.19

Main results of systematic reviews included in the summary (n=33).

| Reference | Summary N. | Main result |

|---|---|---|

| Story, 19998 | 12 | Among schools, the efforts to promote physical activity and healthy diet should be part of a coordinated comprehensive health program. The inclusion of both primary and secondary interventions in a large school health program is recommended. |

| Campbell et al., 20016 | 7 | Two of the long-term studies (one with PA+NE focus against control, and the other only NE versus control) resulted in reduction in the prevalence of obesity. |

| Baranowski et al., 20027 | 20 | In successful interventions, program implementers were not classroom teachers, targeting the interventions to pre-adolescents and adolescents’ groups. However, interventions were intuitively designed and developed, without a theoretical basis. |

| Budd & Volpe, 200612,a | 12 | Greater effectiveness observed in the samples of older children, providing new perspectives on curriculum, designed with the purpose of changing behavior. Physical education classes must be culturally appropriate to the habits practiced outside the school environment, such as active video games. |

| Cole et al., 200613,a | 10 | The Social Cognitive Theory of Bandura was used in eight of ten included studies. This theory and the role of social learning are useful in planning interventions to prevent and treat overweight in childhood. |

| Doak et al., 200611 | 25 | 17 of the 25 interventions showed statistically significant results in lowering BMI. The authors suggest that these proposals can be developed on a large scale and offered for a longer period of time. |

| Sharma, 200610 | 11 | Most interventions aimed at short-term changes immediately after the intervention. In total, the interventions resulted in modest changes in relation to behavior and mixed results on the obesity indicators. High heterogeneity in relation to the measure standards. |

| Flodmark et al., 200614,b | 10+14 | Permanent long-lasting community interventions that promote PA and NE are likely to have more powerful effects than the effects demonstrated for proposals limited to the school environment. |

| Lissau, 200715 | 14 | Half of the studies showed positive effects on reducing obesity. A wide variation in sample characteristics and in theoretical basis of the studies was observed. |

| Sharma, 200716 | 21 | Nine interventions were longer than one school year. Approaches involving parents showed positive results regarding measures of obesity. |

| Kropski et al., 200817 | 14 | Only four of the 14 studies were rated as high quality. Methodological concerns and the small number of publications limits the formulation of inferences about the effectiveness of school interventions. |

| Li et al., 200818 | 22 | Most studies showed beneficial effect of the intervention on one or more outcomes, but all studies had methodological problems. In this sense, the authors highlight the high risk of influence of publication bias. |

| Shaya et al., 200819 | 51 | 13 of the 15 intervention studies reported positive results in some or all quantitative measures. This evidence raises the potential of PA as an element of prevention and reduction of obesity in children. |

| Brown & Summerbell, 200920,c | 15+28 | The results are inconsistent, but generally suggest that PA and NE interventions can control overweight in the long term. |

| Dobbins et al., 200921 | 26 | Four of 14 studies reported positive effects on BMI, with intervention time >nine months. The ten studies that reported no effect on BMI had similarities in combined interventions within the period of time. |

| Jaime & Lock 200922 | 18 | Some current school policies have been effective in improving the food environment and dietary intake in schools, but there is little evaluation of their impact on BMI. |

| Katz, 200923 | 18 | Even with great variability in the measures, methods, and populations, the evidence clearly demonstrated that school interventions had a statistically significant effect in reducing obesity. |

| Pérez-Moralez et al., 200924 | 10 | Most studies did not show a statistically significant reduction in BMI. However, a positive impact on lifestyle was observed in many studies, such as increased consumption of fruits and vegetables and reduced consumption of soft drinks. |

| Zenzen & Kridli, 200925,a | 16 | NE was shown to be an effective method in changing eating habits at school. A program that includes the promotion of healthy lifestyle supported by strong parental influence is also crucial. |

| Brandt et al., 201027 | 22 | School interventions that combine PA and NE were effective, especially in interventions lasting more than one year. |

| Van Cauwenberghe et al., 201028 | 42 | Regarding the magnitude of effects in children, multicomponent interventions aiming at the intake of fruits and vegetables showed strong evidence. In adolescents, educational interventions on behavior showed moderate evidence and multicomponent programs in behavior showed limited evidence. |

| De Bourdeaudhuij et al., 201129 | 11 (27 articles) | Considering the obesity reduction in European children and adolescents, the combination of educational and environmental components may be preferable in interventions in PA and NE. Results of customized educational programs via computer in adolescents are promising. |

| Sharma, 201130 | 25 | Most interventions combined PA and NE strategies, and were implemented by teachers. In terms of activities, almost all interventions had a curricular component, and sought the involvement of parents/family. |

| Silveira et al., 201131 | 24 | The main characteristics of interventions with positive results: duration >1 year, introduction of the proposal in regular school activities, parent involvement, permanent offer of NE in curriculum, and supply of fruits and vegetables by school food services. |

| Yildirim et al., 201126 | 6 | Inconsistent results and the small number of statistically significant effects made the result inconclusive. However, gender (female) and unfavorable values at baseline are the most prominent moderators on the effects of the intervention. |

| Johnson et al., 201232 | 7 | All studies reported benefits in health behaviors and/or anthropometric measurements. Effectiveness was observed when the program objectives were specific, with extended action into the community. |

| Krishnaswami et al., 201233 | 16 | Seven of the 12 anthropometric studies outcomes had at least one positive result. |

| Van Lippevelde et al., 201234 | 5 | Results differ as to parental involvement in health behaviors of children. Interventions that predict parental involvement should include different strategies and approach different determinants and practices. |

| Verstraeten et al., 201235 | 25 | Eight of the 12 studies reported statistically positive effect in reducing BMI. The authors observed the potential of the school environment to improve feeding behavior and PA by promoting the maintenance of a healthy weight. However, the need for further reviews and better designed studies is observed. |

| Lobelo et al., 201336 | 10 | The most successful interventions had primary focus, time longer than six months, involvement of teachers and health professionals, better study designs, and fewer limitations on performance. |

| Quitério, 201337 | 27 | The results of the interventions in PE related to health showed positive and consistent results. However, a considerable number of these interventions did not obtain a reduction in BMI, body fat measures and %BF. |

| Holub et al., 201438 | 15 | Interventions involving Latin populations had inconclusive results. Apart from the deep involvement of appropriately conducted studies, few had significant results in relation to obesity after follow-up. |

| Kelishadi & Azizi-Soleiman 201439 | 32 | School-based interventions can have lasting results in larger groups. Compared to interventions conducted in other environments, the school was the most favorable place for the development of strategies aimed at reducing overweight/obesity, especially when they involve the family. |

PA, physical activity; PE, physical education; NE, nutrition education; % BF, body fat percentage; BMI, body mass index.

Regarding the most frequent recommendations, Table 2 indicates that nine reviews highlighted the effectiveness of interventions with a duration of at least six months.6,11,14,16,20,21,27,31,36 Six reviews also showed the importance of the involvement of parents and/or guardians in intervention strategies.16,25,30,31,34,39 One review17 demonstrated that gender could be a key differentiator for strategy effectiveness: structural interventions were more effective on boys, whereas behavioral interventions were more effective in girls. Finally, the following inconsistencies were observed in a few studies: (i) adequacy of strategies according to the different age groups7,12 (ii) implementation of strategies by teachers7,30,36; (iii) theoretical basis of interventions13,15; (iv) inclusion of strategies in the school curriculum31; and (v) methodological quality of available interventions.17,18,35

DiscussionThis summary was based on data from 33 systematic reviews of interventions developed at the school environment aimed to prevent and/or reduce overweight. A large number of publications recommended the development of continued strategies with at least six months of duration,3,6,11,14,16,20,21,27,31 and that included parents/guardians in the planned contents and/or actions.16,25,30,31,34,39

Duration of interventionsThe evidence assessed in this summary showed the importance of the time variable for interventions to promote positive changes in the practice of PA and/or in the impact of NE on the consumption of fruits and vegetables, resulting in a decrease in overweight.

Nine reviews observed more relevant findings in interventions that had longer periods of time.6,11,14,16,20,21,27,31,36 Some specific time periods were observed, such as “six months,”36 “one school year (seven to nine months),”16,21 and “over one year”.27,31 Apart from the divergence regarding the minimum duration of the intervention to attain positive effects, these recommendations support the theory of Prochaska & DiClemente,40 who identified six months as the minimum time for stabilizing behavior change involving PA practice. Thus, the summary of the available evidence recommends that future interventions carried out in the school environment comprise periods longer than six, for better consolidation of healthy habits.

Throughout the development of this summary, there was a gradual effort on the part of the authors to clarify the issues related to the intervention duration, with specific focus on the most recent systematic reviews. Although Campbell et al. had6 already considered this factor in their 2001 review design, it was not until 2006 that this criterion became more frequent, allowing the authors to explore other intervention characteristics that would indicate more effectiveness in the control and/or prevention of excessive weight gain among children and adolescents.

Complementary to the main finding of this study, two pieces of evidence suggest that, in addition to time, community involvement leads to positive impacts on anthropometric outcomes.14,32 Conversely, evidence recovered from reviews that had a more specific focus suggest that the findings related to the intervention duration are independent from geographic, socioeconomic, or cultural characteristics of the target populations.8,10,18,36

Environment and communityThe findings of this summary also indicate that individual, family, and community variables can influence the adoption of a healthy lifestyle.

Due to its positive effects on the original studies, as the second most frequent recommendation, six systematic reviews recommended the involvement of parents (or guardians) in the interventions.16,25,30,31,34,39 This strategy seeks to extend the impact of healthy behavioral changes beyond the school environment, aiming at extending these changes into the family, so that parents can become role models of healthy habits, favoring the expansion of the child and adolescents’ protection network.

At the individual level, one of the reviews found that positive results in promoting PA and healthy diet could be achieved by adding educational intervention to environmental changes.29 In addition, it was observed that some of the interventions also sought to promote increased access and availability of healthy foods (either at home or in its surroundings), as well as to restrict the consumption of ultra-processed foods and sugary drinks.

For adolescents, the possibility of intervention in the virtual environment, overcoming any barrier regarding distance for participation in programs, represents a feasible alternative for changes in diet and PA. A recent systematic review suggests that interventions offered by technological means (text messages and smartphone applications) have positive impacts both on PA promotion and overweight reduction.41 In this regard, it raises the possibility that future interventions can provide digital content as complementary strategies.

Regarding the community, two reviews indicated that interventions with positive results in diet PA, and body weight had joint actions between the school and the community32,33; one of them included low-income populations.33 Extending the activities to the surrounding community represents the possibility of creating a healthy environment, so that the behavior learned at school can be reproduced in the community in which it is inserted,. This evidence is supported by Shaya et al.,19 who recommended the creation of a collaboration network among community schools.

Finally, De Bourdeaudhuij et al.,14 in a review that considered only individual and environmental strategies, observed that the use of computers as an educational tool showed consistent results for both PA level changes and changes in the nutritional status of students.

Age and genderAmong the main results from the review by Budd and Volpe,12 it was observed that samples with older age responded better to interventions, benefitting more from its contents. Moreover, interventions that promoted greater energy expenditure within the school environment, aiming at compensating the low energy expenditure of leisure activities outside school, were considered to be appropriate strategies.

Brown and Summerbell20 found that younger and female children had better results with the interventions. Regarding the review by Van Cauwenberghe et al.,28 which involved interventions carried out in European countries, it was observed that educational interventions led to behavior change in adolescents, and that encouraging the consumption of fruits and vegetables had an effect on children, but with inconsistent results regarding anthropometric variables. One hypothesis for this controversial result lies on the design of the analyzed studies.

While the studies selected by Brown and Summerbell were community trials, the interventions analyzed by Budd and Volpi were randomized controlled trials, that is, the latter had greater control of external variables that could interfere in the final results. Conversely, the review by Kropski et al.,17 in addition to having as differential the quality classification of the included articles, found that girls and boys respond better to different types of interventions: structural interventions have greater impact on boys and behavioral interventions result in deeper changes in girls.

Theoretical basis of interventionsAn important aspect, albeit little explored in most studies, is the theoretical models used for the preparation and implementation of programs. These models help researchers to observe and analyze a theoretical object. In the case of interventions to modify PA levels or eating habits, a theoretical model helps in the intervention design, variable selection, form of analysis, and evaluation of interventions.

In the descriptive summary, only two published reviews aimed to investigate the theoretical models used in interventions conducted at the school environment. The absence of a solid reference can lead to doubts or inconsistencies regarding the variables to be analyzed and how to perform, evaluate, and analyze the process, which may explain in part the difficulty of many studies to measure or even prove the effectiveness of their interventions. Baranowski et al.,7 when analyzing 20 studies, found that one of the difficulties was the lack of a theoretical basis for the design and implementation of interventions at the school environment. Such limitation was also emphasized by Cole et al.,13 who identified eight interventions based on Albert Bandura's social cognitive theory (SCT). For the record, interventions based on the SCT consider both the social characteristics of children who receive the intervention and the potential action of teachers, who in turn, will be responsible for implementing the strategies.

The lack of a theoretical basis to support an educational intervention can be seen as a reflection of the biological education of health professionals, ignoring or giving little value to different aspects of learning at each age group. This characteristic is observed in studies where the authors work with broader age ranges, offering the same activity protocol to all, without any adjustment to age group and/or gender. In this sense, observing that many studies do not even mention the theoretical model of intervention, it is reasonable to wonder whether the absence of satisfactory results is not due to the limited capacity of the studies (in terms of the specificity of the intervention structure) but rather to the degree of comprehension of the problem by the researchers.

Moderating variablesThe analysis of the included publications demonstrated that one of the main objectives of an intervention involving the promotion of PA and/or NE in children and adolescents is to promote a healthy behavior pattern. However, there are different variables that, when included among the proposed interventions and their outcomes, can produce different results in individuals or groups; they are called moderating variables. Based on the review by Yildirim et al.,26 which aimed to identify which moderating variables were more consistent in the analyzed interventions, it could be observed that female individuals and those with worse indicators of obesity at the beginning of the intervention showed better results in the analyzed interventions.

LimitationsThe main limitation of this research lies in the fact that the phases of reading and data extraction of the reviews were conducted by a single investigator (PG). Seeking to minimize the loss of relevant evidence, articles were excluded only when elements other than those of interest for the present research were identified in full texts.

Another limitation of this study is the difficulty in comparing studies, given the great heterogeneity between the methods used by the included systematic reviews; for this reason, the present study was designed to give feasible recommendations to be implemented in school units that showed to be more effective in the prevention/reduction of overweight in children and adolescents. Moreover, it focused on specific aspects for further studies in this line of research.

ConclusionsThe available evidence allows for the recommendation of future strategies that consider long-term interventions involving not only children and adolescents, but also their parents or guardians. Additionally, it was observed that boys respond more effectively to structural interventions, whereas girls respond better to behavioral interventions. In contrast, this summary highlights the need for further studies to test different theoretical models of interventions, to identify the best strategies regarding gender and age of the participants, and to determine which are the moderating variables for overweight.

FundingPaulo H Guerra is a postdoctoral fellow of Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo_FAPESP (Case: 2013/22204-7). This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

This work is dedicated to Eduardo Vieira Guerra, that was born in the date that we received the first review of this manuscript. His coming into the world bring us a lot of joy and motivation.

Please cite this article as: Guerra PH, Silveira JA, Salvador EP. Physical activity and nutrition education at the school environment aimed at preventing childhood obesity: evidence from systematic reviews. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2016;92:15–23.