To estimate the costs of hospitalization in premature infants exposed or not to antenatal corticosteroids (ACS).

MethodRetrospective cohort analysis of premature infants with gestational age of 26–32 weeks without congenital malformations, born between January of 2006 and December of 2009 in a tertiary, public university hospital. Maternal and neonatal demographic data, neonatal morbidities, and hospital inpatient services during the hospitalization were collected. The costs were analyzed using the microcosting technique.

ResultsOf 220 patients that met the inclusion criteria, 211 (96%) charts were reviewed: 170 newborns received at least one dose of antenatal corticosteroid and 41 did not receive the antenatal medication. There was a 14–37% reduction of the different cost components in infants exposed to ACS when the entire population was analyzed, without statistical significance. Regarding premature infants who were discharged alive, there was a 24–47% reduction of the components of the hospital services costs for the ACS group, with a significant decrease in the length of stay in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). In very-low birth weight infants, considering only the survivors, ACS promoted a 30–50% reduction of all elements of the costs, with a 36% decrease in the total cost (p=0.008). The survivors with gestational age <30 weeks showed a decrease in the total cost of 38% (p=0.008) and a 49% reduction of NICU length of stay (p=0.011).

ConclusionACS reduces the costs of hospitalization of premature infants who are discharged alive, especially those with very low birth weight and <30 weeks of gestational age.

Estimar os custos da internação hospitalar de prematuros, cujas mães receberam ou não corticoide antenatal (CEA).

MétodoCoorte retrospectiva de prematuros sem malformações congênitas com idade gestacional de 26 a 32 semanas, nascidos entre janeiro/2006 e dezembro/2009, em hospital público, terciário e universitário brasileiro. Coletaram-se dados demográficos maternos e dos recém-nascidos (RN), a morbidade neonatal e utilização de recursos de saúde durante a internação hospitalar. Os custos foram analisados pela técnica de microcosting.

ResultadosDos 220 nascidos que obedeciam a critérios de inclusão, 211 (96%) prontuários foram revisados: 170 receberam CEA e 41 não receberam a medicação. Analisando-se toda a população, houve redução de 14-37% entre os diferentes componentes do custo nos pacientes expostos ao CEA, sem significância estatística. Na análise de prematuros que receberam alta hospitalar vivos, o grupo com CEA teve redução de 24-47% nos vários componentes dos custos hospitalares, com diminuição significante dos dias de internação em terapia intensiva. Os nascidos com peso <1500g, considerando-se somente os sobreviventes, são aqueles que mais se beneficiaram da administração do CEA, com redução significante de todos componentes dos custos em 30-50%, sendo tal diminuição de 36% no custo total (p=0,008). Para o grupo com idade gestacional <30 semanas, também sobreviventes, houve diminuição do custo total de 38% (p=0,008) e redução de 49% dos dias de internação em UTI neonatal (p=0,011).

ConclusõesO CEA reduz o custo hospitalar de prematuros que sobrevivem à internação após o parto, principalmente naqueles abaixo de 1500g e 30 semanas de idade gestacional.

There has been great progress in reducing child mortality in the last two decades.1,2 Since 1990, the global neonatal mortality rate was reduced by 37%, from 33 to 21 deaths per 1000 live births,3 and now the World Health Organization (WHO), with the Every Newborn program, proposes a reduction to 10 deaths per 1000 live births until the year 2035. For this goal to be achieved, it will be necessary to increase the use of effective interventions to reduce the leading causes of neonatal deaths, particularly prematurity.4

Antenatal corticosteroids (ACS) participate in this context as one of the proven effective interventions to reduce complications of prematurity, as they induce fetal maturity.5 In 2010, a systematic review6 of 18 randomized controlled trials involving the use of ACS was conducted in 14 high-income countries that participated in the meta-analysis of the Cochrane Library5 and in four middle-income countries, including Brazil. While the Cochrane meta-analysis suggested that ACS reduced neonatal mortality by 31%, the new review showed that ACS decreased neonatal mortality by 53% (RR 0.47; 95% CI: 0.35–0.64) and neonatal morbidity by 37% (RR: 0.63; 95% CI: 0.49–0.81). It is believed that, in low-income countries with few neonatal intensive care resources, the beneficial effects of corticosteroids in reducing neonatal morbidity and mortality could be even greater.6

Data on the use of ACS in Brazil demonstrate that much remains to be done to increase its prescription to Brazilian pregnant women. The Brazilian Neonatal Research Network annual report in 2012, involving 20 Brazilian university hospitals, showed low use of ACS: 67% of pregnant women who gave birth to preterm infants weighing less than 1500g received the antenatal medication (ranging from 62% to 75% among the centers).7

Among preterm infants with birth weight <1000g, a recent study in the Brazilian population demonstrated that two thirds of them received ACS.8 It is noteworthy that the WHO considers ACS as a priority intervention for the prevention of prematurity complications.9,10 It is unacceptable that countries with high rates of prematurity, such as Brazil, do not universally use ACS for risk pregnancies, which demonstrates missed opportunities to increase the chance of survival of preterm infants.

If ACS use was prevalent in Brazil, there could be a reduction in morbidity and mortality associated with prematurity and, consequently, in hospital costs. In 1991, Mugford et al.11 estimated that the administration of corticosteroids to pregnant women with less than 35 weeks of gestational age (GA) would reduce the mean costs per infant by 10%, with a 14% decrease in the mean cost per survivor. In another study involving ACS and costs, published in 1995, Simpson & Lynch12 used an analytical decision-making model and estimated a reduction of three to 17 deaths and cost savings of 200,000 to 500,000 dollars per 100 babies exposed to ACS.

In Brazil, there have been few studies involving costs related to preterm infants whose mothers received or not ACS. Therefore, the present study aimed to analyze the hospital costs of hospitalization of preterm infants born in a Brazilian public university hospital exposed to antenatal corticosteroids, compared to those who were not.

MethodsThis was a retrospective analysis of a cohort of preterm infants born between January of 2006 and December of 2009, after it was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the institution. Preterm infants born between 26 and 32 weeks GA, as determined by the best obstetric estimate, were included in the analysis. Infants with congenital malformations were excluded.13

Data were collected from the neonatal unit of Hospital Universitário da Escola Paulista de Medicina–Universidade Federal de São Paulo, a tertiary public hospital whose neonatal unit is classified as Level III by the National Register of Healthcare Facilities (Cadastro Nacional de Estabelecimentos de Saúde [CNES]).14 At the time of the study, the unit had eight intensive care beds, eight conventional neonatal intermediate care beds, and four intermediate kangaroo-care beds. The maternity ward treated approximately 1000 newborns a year, and is specialized in pregnant women with severe medical or obstetric complications and/or fetuses with clinical diseases or malformations. Of the total number of births, 30–40% were admitted to the neonatal unit annually.

Maternal demographic data, pregnancy complications, information about delivery, and neonatal demographic data were collected from medical records of newborns. Data on ACS administration was assessed, considering infants as belonging to the group exposed to corticosteroids if the mother had received any dose of the medication for the purpose of fetal maturation. Data were also collected on neonatal morbidity and days of hospitalization, divided into neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) and intermediate care units.

The cost analysis was conducted using the microcosting process,15 which identifies and measures each resource used by assigning them values and integrating this information. Thus, the costs were divided into respiratory, laboratory, medication, tests, hospital daily rates, and total costs, defined as follows:

- •

Respiratory cost: evaluation of mechanical ventilation time, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), and inhaled oxygen therapy, in addition to the need for and number of surfactant doses administered. The estimated respiratory cost was based on the maintenance costs of mechanical ventilators, the CPAP circuit, gas consumption (oxygen) by the mechanical ventilation equipment, and cubic meter of oxygen. Therefore, a daily mechanical ventilation rate was calculated, as well as that of CPAP and oxygen inhalation, in addition to the cost of the surfactant dose, using the drug price list by the National Health Surveillance Agency (Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária [ANVISA]).16

- •

Laboratory cost: all laboratory tests performed during hospitalization and costs were provided by the central laboratory of the hospital. Costs of tests performed at the unit, such as glycemia and capillary hematocrit, were also estimated, taking into account only the cost of materials provided by the hospital's purchasing department.

- •

Imaging test costs and others: all imaging tests (X-rays, ultrasound, computed tomography [CT], magnetic resonance imaging [MRI], and contrast studies), echocardiogram and electrocardiogram (ECG), fundus examination, otoacoustic emissions, and neonatal screening for inborn errors of metabolism were considered. The costs were estimated based on the payment system of the Brazilian Unified Health System (Sistema Único de Saúde [SUS]).

- •

Nutritional cost: comprised the daily neonatal parenteral nutrition cost, whose value was provided by the hospital pharmacy, as well as the cost of enteral feeding, calculated with the help of the Unit's nutritionist, through the mean consumption of preterm and term infants formula and the market price of the formula.

- •

Cost of medications: the cost of the materials used for drug administration, whether by infusion pump or direct administration, was calculated. It was also verified, through the nursing staff, the duration of antibiotics and drugs reused after the bottles were opened. The mean cost of drugs was estimated based on March 2013 ANVISA's price list16 (conformity list), considering the maximum selling price to the government.

- •

Hospital daily rates: considering the rates provided by the hospital accounting department, direct costs were verified (wages) at the cost center of the neonatal unit and indirect costs (electricity, water, and sewage system), as well as the costs of cleaning and office supplies and distribution of costs from other hospital sectors.

At the time of the study, the team had 54 nurses, two physical therapists, and five attending physicians who were included in the hospital cost sheets. As for the other members of the medical staff (assistants, professors, and residents) and other professionals (speech therapists, nutritionists, pharmacists, and social workers), they were not included in the unit cost sheets, as they were employees of the university. Thus, the mean costs during the study period were calculated and divided by the number of patients admitted to the unit in the same period, yielding a daily cost per patient of USD 142.00. To calculate this cost component, the number of hospitalization days was multiplied by the estimated hospital daily rate.

- •

Total cost: comprised the respiratory costs, medications, nutritional costs, and laboratory tests, as well as other costs with blood therapy, phototherapy, cost of catheters, surgeries, and other eventual procedures, in addition to the hospital rates.

Aiming to compare the study results with international studies, the costs were converted from Brazilian reals to US dollars at an exchange rate of 2.249 (mean annual rate in 2013).17

For the statistical analysis, categorical variables were expressed by the number and frequency of each event in the study groups, and compared by Pearson's chi-squared test or Fisher's exact test. Numerical variables were expressed as means and compared by Student's t-test or Mann–Whitney test, according to data normality. To compare the clinical outcomes between the groups with and without ACS, relative risks and confidence intervals were calculated. SPSS (SPSS Inc. Released 2008. SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 17.0, IL, USA) and EPI INFO (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, version 7, GA, USA) were used for the statistical analysis. Significance level was set at 0.05 for all tests.

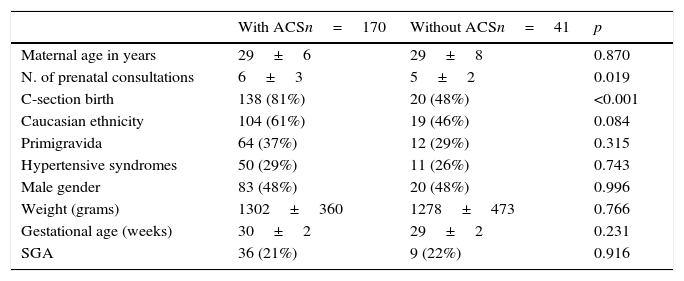

ResultsDuring the study period, 220 neonates between 26 and 32 completed weeks of GA met the inclusion criteria. Of these, nine records were lost and 211 (96%) were reviewed, of which 170 (80%) received at least one dose of ACS and 41 (20%) did not receive the medication. The demographic data of the groups are shown in Table 1 and those related to neonatal morbidity are shown in Table 2.

Maternal demographic characteristics and of newborns exposed or not to antenatal corticosteroids (ACS), expressed in number (%) or mean±standard deviation.

| With ACSn=170 | Without ACSn=41 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age in years | 29±6 | 29±8 | 0.870 |

| N. of prenatal consultations | 6±3 | 5±2 | 0.019 |

| C-section birth | 138 (81%) | 20 (48%) | <0.001 |

| Caucasian ethnicity | 104 (61%) | 19 (46%) | 0.084 |

| Primigravida | 64 (37%) | 12 (29%) | 0.315 |

| Hypertensive syndromes | 50 (29%) | 11 (26%) | 0.743 |

| Male gender | 83 (48%) | 20 (48%) | 0.996 |

| Weight (grams) | 1302±360 | 1278±473 | 0.766 |

| Gestational age (weeks) | 30±2 | 29±2 | 0.231 |

| SGA | 36 (21%) | 9 (22%) | 0.916 |

SGA, small for gestational age.

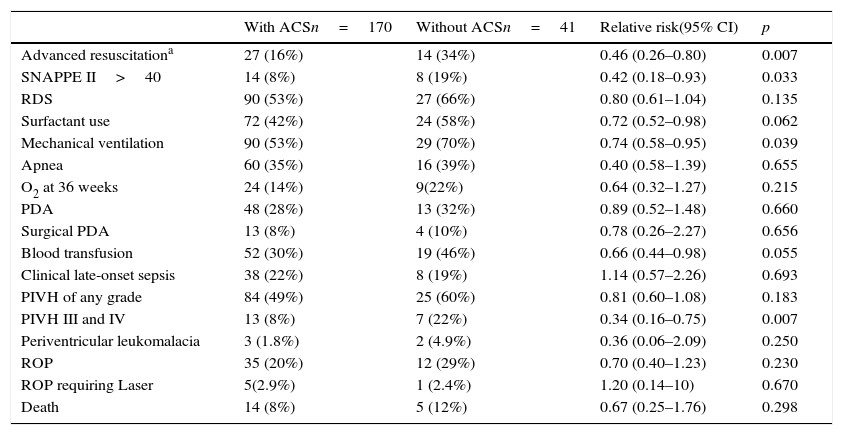

Morbidity of newborns exposed to antenatal corticosteroids (ACS) or not, expressed in numbers (%) and relative risk with 95%confidence interval (95% CI).

| With ACSn=170 | Without ACSn=41 | Relative risk(95% CI) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Advanced resuscitationa | 27 (16%) | 14 (34%) | 0.46 (0.26–0.80) | 0.007 |

| SNAPPE II>40 | 14 (8%) | 8 (19%) | 0.42 (0.18–0.93) | 0.033 |

| RDS | 90 (53%) | 27 (66%) | 0.80 (0.61–1.04) | 0.135 |

| Surfactant use | 72 (42%) | 24 (58%) | 0.72 (0.52–0.98) | 0.062 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 90 (53%) | 29 (70%) | 0.74 (0.58–0.95) | 0.039 |

| Apnea | 60 (35%) | 16 (39%) | 0.40 (0.58–1.39) | 0.655 |

| O2 at 36 weeks | 24 (14%) | 9(22%) | 0.64 (0.32–1.27) | 0.215 |

| PDA | 48 (28%) | 13 (32%) | 0.89 (0.52–1.48) | 0.660 |

| Surgical PDA | 13 (8%) | 4 (10%) | 0.78 (0.26–2.27) | 0.656 |

| Blood transfusion | 52 (30%) | 19 (46%) | 0.66 (0.44–0.98) | 0.055 |

| Clinical late-onset sepsis | 38 (22%) | 8 (19%) | 1.14 (0.57–2.26) | 0.693 |

| PIVH of any grade | 84 (49%) | 25 (60%) | 0.81 (0.60–1.08) | 0.183 |

| PIVH III and IV | 13 (8%) | 7 (22%) | 0.34 (0.16–0.75) | 0.007 |

| Periventricular leukomalacia | 3 (1.8%) | 2 (4.9%) | 0.36 (0.06–2.09) | 0.250 |

| ROP | 35 (20%) | 12 (29%) | 0.70 (0.40–1.23) | 0.230 |

| ROP requiring Laser | 5(2.9%) | 1 (2.4%) | 1.20 (0.14–10) | 0.670 |

| Death | 14 (8%) | 5 (12%) | 0.67 (0.25–1.76) | 0.298 |

SNAPPEII, Score for Neonatal Acute Physiology Perinatal Extension II; RDS, respiratory distress syndrome; PDA, Patent ductus arteriosus; PIVH, peri-intraventricular hemorrhage; ROP, Retinopathy of prematurity.

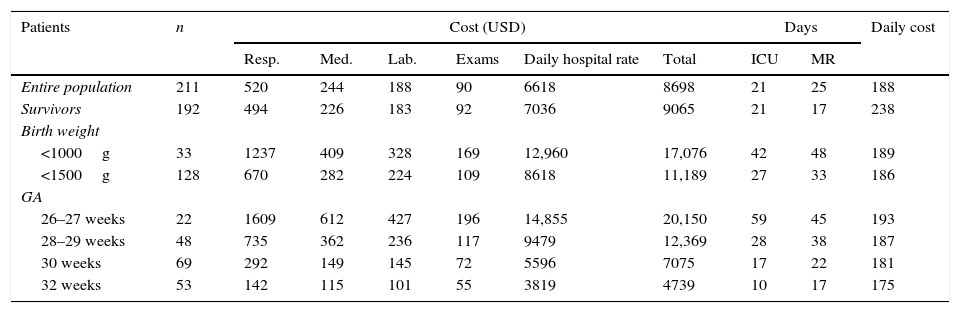

Table 3 shows the mean hospital costs subdivided among its main components, and also the mean days of hospitalization in the NICU and intermediate care unit for the entire study population and for the survivors; the latter were subdivided between those weighing less than 1000g and 1500g and in different GA ranges. The costs of all the components increased as birth weight and GA decreased. The highest cost component was that related to staff salary, here encompassed by hospital daily rates.

Average cost in US dollars, subdivided among its five components, days of intensive care unit (ICU) stay and medium risk, with daily costs for the entire study population, for those that were discharged alive and according to different weight and gestational age ranges.

| Patients | n | Cost (USD) | Days | Daily cost | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resp. | Med. | Lab. | Exams | Daily hospital rate | Total | ICU | MR | |||

| Entire population | 211 | 520 | 244 | 188 | 90 | 6618 | 8698 | 21 | 25 | 188 |

| Survivors | 192 | 494 | 226 | 183 | 92 | 7036 | 9065 | 21 | 17 | 238 |

| Birth weight | ||||||||||

| <1000g | 33 | 1237 | 409 | 328 | 169 | 12,960 | 17,076 | 42 | 48 | 189 |

| <1500g | 128 | 670 | 282 | 224 | 109 | 8618 | 11,189 | 27 | 33 | 186 |

| GA | ||||||||||

| 26–27 weeks | 22 | 1609 | 612 | 427 | 196 | 14,855 | 20,150 | 59 | 45 | 193 |

| 28–29 weeks | 48 | 735 | 362 | 236 | 117 | 9479 | 12,369 | 28 | 38 | 187 |

| 30 weeks | 69 | 292 | 149 | 145 | 72 | 5596 | 7075 | 17 | 22 | 181 |

| 32 weeks | 53 | 142 | 115 | 101 | 55 | 3819 | 4739 | 10 | 17 | 175 |

GA, gestational age; Resp, respiratory costs; Med, medication costs; Lab, laboratory costs; Exams, examination costs, except laboratory; Daily, daily hospital rate; ICU days, days of hospitalization in intensive care unit; MR days, days of hospitalization at medium risk.

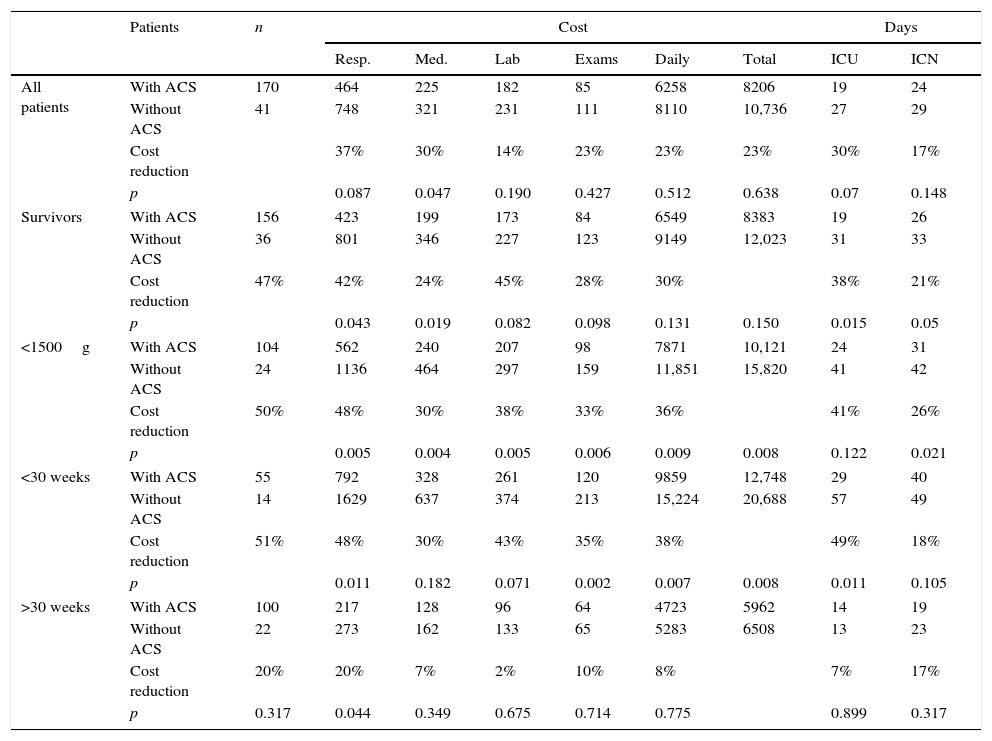

Table 4 shows the costs according to several categories of the analyzed sample, comparing hospital costs among newborns exposed or not to ACS. For the entire study population, there was no cost reduction with statistical significance between the groups, although an absolute reduction of 14–37% between the different cost components in patients receiving ACS was observed. At the analysis of preterm infants that were discharged alive, the group exposed to ACS showed a reduction of 24–47% in the various cost components, with statistical significance for the respiratory and drug components and significant decrease in hospital length of stay.

Average cost in US dollars, subdivided among its five components, days of intensive care unit (ICU) stay and medium risk for all patients, for those that were discharged alive, according to different weight and gestational age ranges, classified according to exposure to antenatal corticosteroids (ACS) or not.

| Patients | n | Cost | Days | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resp. | Med. | Lab | Exams | Daily | Total | ICU | ICN | |||

| All patients | With ACS | 170 | 464 | 225 | 182 | 85 | 6258 | 8206 | 19 | 24 |

| Without ACS | 41 | 748 | 321 | 231 | 111 | 8110 | 10,736 | 27 | 29 | |

| Cost reduction | 37% | 30% | 14% | 23% | 23% | 23% | 30% | 17% | ||

| p | 0.087 | 0.047 | 0.190 | 0.427 | 0.512 | 0.638 | 0.07 | 0.148 | ||

| Survivors | With ACS | 156 | 423 | 199 | 173 | 84 | 6549 | 8383 | 19 | 26 |

| Without ACS | 36 | 801 | 346 | 227 | 123 | 9149 | 12,023 | 31 | 33 | |

| Cost reduction | 47% | 42% | 24% | 45% | 28% | 30% | 38% | 21% | ||

| p | 0.043 | 0.019 | 0.082 | 0.098 | 0.131 | 0.150 | 0.015 | 0.05 | ||

| <1500g | With ACS | 104 | 562 | 240 | 207 | 98 | 7871 | 10,121 | 24 | 31 |

| Without ACS | 24 | 1136 | 464 | 297 | 159 | 11,851 | 15,820 | 41 | 42 | |

| Cost reduction | 50% | 48% | 30% | 38% | 33% | 36% | 41% | 26% | ||

| p | 0.005 | 0.004 | 0.005 | 0.006 | 0.009 | 0.008 | 0.122 | 0.021 | ||

| <30 weeks | With ACS | 55 | 792 | 328 | 261 | 120 | 9859 | 12,748 | 29 | 40 |

| Without ACS | 14 | 1629 | 637 | 374 | 213 | 15,224 | 20,688 | 57 | 49 | |

| Cost reduction | 51% | 48% | 30% | 43% | 35% | 38% | 49% | 18% | ||

| p | 0.011 | 0.182 | 0.071 | 0.002 | 0.007 | 0.008 | 0.011 | 0.105 | ||

| >30 weeks | With ACS | 100 | 217 | 128 | 96 | 64 | 4723 | 5962 | 14 | 19 |

| Without ACS | 22 | 273 | 162 | 133 | 65 | 5283 | 6508 | 13 | 23 | |

| Cost reduction | 20% | 20% | 7% | 2% | 10% | 8% | 7% | 17% | ||

| p | 0.317 | 0.044 | 0.349 | 0.675 | 0.714 | 0.775 | 0.899 | 0.317 | ||

Resp, respiratory costs; Med, medication costs; Lab, laboratory costs; Exams, examination costs, except laboratory; Daily, daily hospital rate; ICU days, days of hospitalization in intensive care unit; ICN, intermediate care nursery.

The group of newborns with birthweight <1500g, also considering only the survivors, benefited the most from ACS administration, with significant reduction in all cost components, ranging from 30% to 50%, with a decrease of 36% in the total cost (p=0.008). For the group of neonates with GA <30 weeks and survivors, a significant reduction of some of the cost components and decrease in the total cost of 38% (p=0.008) were observed, accompanied by a reduction of 49% in days of hospitalization in the NICU (p=0.011).

DiscussionThe results of this study showed a significant reduction in several components of hospital costs of preterm infants submitted to ACS therapy in Brazil, which are more evident in those who were discharged alive, with birth weight <1500g, and/or GA <30 weeks. It is noteworthy that, from a clinical point of view, preterm infants exposed to ACS, when compared to those who were not, had less need for resuscitation in the delivery room, lower SNAPPE II,18 and less need for mechanical ventilation, similar to the results reported to date for Brazilian neonates.19

Therefore, this study, a pioneer in a developing country such as Brazil, reinforces the WHO guidelines in its aim to reduce neonatal mortality, demonstrating the benefits of universal ACS for pregnant women at risk for preterm delivery, now considering the financial aspects and decrease in healthcare costs.

For four decades, ACS therapy for women at risk of preterm delivery has been recommended as one of the most effective interventions to reduce neonatal mortality and morbidity.5,10 Considering the previously demonstrated benefits, not using ACS is considered bad practice in developed countries. Therefore, this study had to be retrospective, focusing on the use of healthcare resources and hospital costs.

With advances in neonatal intensive care, preterm survival is increasing, albeit accompanied by an increase in hospital costs. Petrous et al.20 retrieved 19 publications that analyzed the initial costs of hospitalization of preterm infants and observed huge differences in cost estimates between the studies, making comparisons difficult. The authors provide a number of explanations for this variability, emphasizing the difference between the time when the studies were conducted and geographic diversity, which may reflect variations in medical practices and healthcare organizations. Nonetheless, there is a consistent inverse association between hospitalization costs and GA or birthweight, similar to the results obtained in the present study.

In that review, the initial costs of hospitalization were shown to be related to preterm mortality, being higher among the survivors. Thus, it was decided that the present study would make separate analyses for the entire population and for the survivors, taking into account the morbidity and resource utilization during hospital stay.

Regarding the difference between the several hospital cost components, it was observed that wages and indirect costs accounted for 76% of the total costs, and the direct costs, for 24%; the latter were divided into respiratory costs, 25%; pharmacy, 12%; radiology, 5%; laboratory, 9%; and others (nutrition, procedures, blood therapy, etc.), 49%. These results are similar to those obtained when analyzing 25 units of the Vermont Oxford network, which collects data on preterm infants whose birth weight is lower than 1500g: accommodation costs, which include salaries and costs on equipment and daily rates, accounted for 72% of the total cost, while the direct costs amounted to 28% (respiratory, 22%; laboratory, 24%; radiology, 7%; pharmacy, 16%; and others, 31%).21

Some Brazilian publications have analyzed the cost of treating preterm infants. In 2011, Desgualdo et al.22 evaluated hospital costs for newborns with 22 to 36 weeks GA who were born in a referral hospital in São Paulo, Brazil. The authors showed that the mean cost per day for preterm infants whose weight was <1000g was USD 115.00.

More recently, Mwamakamba et al.23 estimated the direct hospital costs of 84 preterm infants with 22–36 weeks GA, born to adolescent mothers in a tertiary public hospital in São Paulo, Brazil. In that study, the highest cost component was hospital services (72%); the mean cost for those weighing less than 1000g was USD 8930.00, with a mean daily cost of USD 157.00. Despite the different methodology, the daily cost value for preterm infants weighing less than 1000g found in the present study was estimated at USD 189.00, a value comparable to that described by Mwamakamba et al.,23 especially when considering the fact that those authors did not consider indirect hospital costs, which may correspond to 16% of the total cost.

There are a few publications in the literature showing the impact of ACS on cost reduction. The first meta-analysis conducted by Crowley et al.24 in 1990 mentions a decrease of USD 17,300.00 in mean hospital costs associated with antenatal corticosteroid therapy, based on the findings of a single study. In 1991, Mugford estimated a decrease in hospital costs of patients with ACS, taking as reference the cost of care for patients with and without respiratory distress syndrome. The use of ACS for pregnant women under 35 weeks gestation would reduce the mean cost per infant by 10% and the mean cost per survivor by 14%.10

The study by Carlan et al.25 estimated a reduction of resources associated with ACS, with a decrease of seven days in hospital length of stay and of USD 5000.00 in costs. Based on the study by Simpson & Lynch,12 the cost reduction estimate promoted by ACS was 19%. The results of the present study showed a reduction in hospital costs associated with antenatal corticosteroids ranging from 23% to 38%, depending on the weight and GA, which are considerable values that must be considered in an attempt to expand the prescription of ACS to Brazilian pregnant women at risk of premature birth. Considering the national scenario, where approximately 40,000 preterm infants with birth weight <1500g are born annually,26 and based on a cost difference of USD 6000 found in this study among very-low birth weight neonates exposed or not to ACS, a decrease in costs of approximately 230 million dollars a year can be estimated, if the antenatal medication was administered to 95% of pregnant women with threatened labor.

It is worth mentioning the study's limitations regarding cost estimates, highlighting the fact that these data are from a single tertiary and teaching hospital, which makes it difficult to compare it with non-university and/or smaller hospitals; the lack of a single cost estimate system among Brazilian public hospitals; and the small sample of patients, particularly the lower GA groups that did not receive ACS.

However, regarding costs, it can be stated that there is a huge variation in the data analysis methods reported in the literature20 and the objective was to attain an approximation of hospital costs to compare the newborns exposed to ACS or to those who were not exposed. Despite these limitations, it was a pioneering study in Brazil, comparing the economic impact of antenatal medication according to WHO guidelines that encourage the use of simple and effective technologies in low and middle-income countries to reach the global aim of reducing neonatal mortality by the year 2035.

It can be concluded that the use of ACS is a simple measure that contributes to reduce prematurity complications and the use of health resources, reducing hospital costs for preterm infants with GA between 26 and 32 weeks in Brazil. This effect is predominant among those weighing <1500g and/or under 30 weeks GA who survive until hospital discharge.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Ogata JF, Fonseca MC, Miyoshi MH, Almeida MF, Guinsburg R. Costs of hospitalization in preterm infants: impact of antenatal steroid therapy. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2016;92:24–31.

Discipline of Neonatal Pediatrics, Escola Paulista de Medicina (EPM), Universidade Federal de São Paulo (UNIFESP), São Paulo, SP, Brazil.