The aim of this study was to identify the pattern of pediatric dermatoses of patients evaluated at a dermatologic clinic of a reference center in Brazil and to compare these results to similar surveys conducted in other countries.

MethodsA retrospective study was performed of patients up to 18 years old, evaluated at a dermatologic clinic between January 1, 2017 and December 31, 2017. Variables collected for analysis included age, gender, dermatological diagnosis, multidisciplinary follow-up, hospitalization, and complementary exams.

ResultsA total of 2330 patients were included for analysis, with a mean age of 9.7 years. 295 patients were diagnosed with more than one skin disease, leading to a total of 2668 diagnoses. Skin diseases were organized into categories and inflammatory dermatoses corresponded to the largest group (31.2%), mostly due to atopic dermatitis (18.3%). The other main categories were: genodermatoses (14.2%), infectious diseases (12.6%), adnexal disorders (12.5%), cysts and neoplasms (10.7%), and vascular disorders (7.0%). Fifty-six patients needed to be admitted to the dermatology ward; 25 of them (44.6%) for management of worsening of the skin disease, mainly atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, and drug reactions. There were 885 biopsies performed in 38.0% of the subjects and 751 patients (32.2%) required multidisciplinary care; most of them had some genodermatoses.

ConclusionsDermatologic disorders are very common in the pediatric age group and differ from those in adults, suffering influence from cultural, ethnic, socioeconomic, and environmental factors. Knowing the magnitude and distribution of these dermatoses is important to better plan healthcare policies.

Dermatological complaints correspond up to 30% of pediatric consultations in primary health care.1,2 Ethnic, socioeconomic, and environmental factors influence the incidence of dermatoses, and the disease pattern in the pediatric population differs from that observed in adults.3 Not only does the prevalence of certain conditions vary among age groups, but there are also differences in clinical presentation, therapeutic response, risk of extra-cutaneous involvement, associated comorbidities, and prognosis; even risk factors may diverge in adults and children when the same disease is studied.3

Due to the high prevalence of dermatoses considered non-severe, there may be a misinterpretation that dermatological diseases do not cause a high impact either on the patient or on the health system. However, when considering disability, sequelae, and years of life lived with disability, conditions considered simple, like eczema and acne vulgaris, may cause an important psychological burden on the individual and may represent a high cost to the health system. In childhood, this impact can be even more important, given that skin diseases can influence self-esteem and generate an important family distress.4–7

The pattern of skin diseases is known to vary in different countries and in different regions of the same country.8 Considering the need for better resource allocation in clinical care and research, it is mandatory to know the populations’ requirements and the existing issues.6,9,10 Epidemiologic surveys of the pediatric age group have been conducted in numerous countries, such as Brazil, Greece, Turkey, India, Mexico, Switzerland, and China, allowing an overview of the pediatric dermatology scenario.3,9,11–20

The aim of this study was to identify the pattern of pediatric dermatoses of patients evaluated at a dermatologic clinic of a reference center in Brazil.

Materials and methodsThe authors performed a retrospective study of patients aged up to 18 years evaluated at the Dermatology Division of the Hospital das Clínicas of the University of São Paulo Medical School (HC-FMUSP), São Paulo, Brazil, during a period of one year, between January 1, 2017 and December 31, 2017.

Data were obtained from the internal database of Hospital das Clínicas and patients’ medical records. Variables collected for analysis were patient age, gender, dermatological diagnosis, multidisciplinary follow-up, hospitalization, and complementary testing for diagnostic elucidation, such as histopathology, direct and indirect immunofluorescence, direct mycological examination, microscopy for detection of parasites, Wood's lamp exam, and immunomapping. Patients with incomplete chart data were excluded.

The descriptive analysis of categorical variables was calculated as absolute (n) and relative (%) frequencies. Microsoft Excel was used for data analysis.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of HC-FMUSP.

ResultsDemographicsDuring the one-year period, 2356 patients aged up to 18 years were evaluated in the Dermatology Division of HC-FMUSP. Twenty-six subjects were excluded from the analysis due to incomplete data. Of 2330 patients evaluated, 52.4% were female and 47.6% were male. 295 patients were diagnosed with more than one skin disease, leading to a total of 2668 diagnoses. The mean age was 9.7 years and patients were classified into age groups, based on similar studies3,21 as follows: 59 (2.5%) infants (0–<12 months), 123 (5.3%) toddlers (12–<24 months), 446 (19.2%) preschoolers (24 months to <6 years), 723 (31.0%) schoolchildren (6–<12 years), and 979 (42.0%) adolescents (12–18 years).

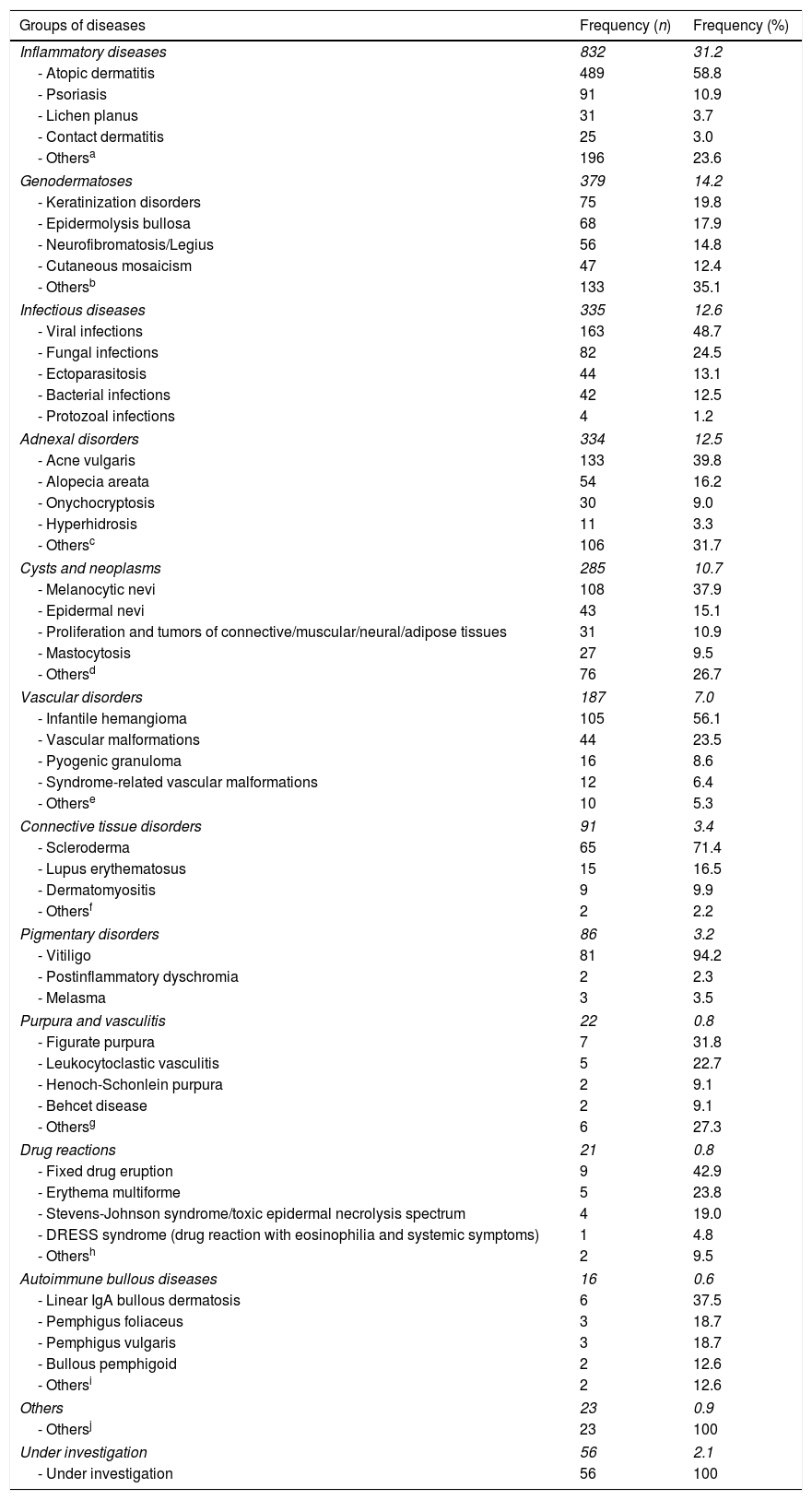

Dermatologic diagnosisSkin diseases were grouped in 13 categories: inflammatory diseases; genodermatoses; infectious diseases; adnexal disorders; cysts and neoplasms; vascular disorders; connective tissue disorders; pigmentary disorders; purpura and vasculitis; drug reactions; autoimmune bullous diseases; diseases under investigation (cases in which a specific diagnosis could not be concluded), and other diseases not otherwise classified (cases that could not be classified in any of the previous categories).

The most frequent category was inflammatory diseases, with 832 patients (31.2%). Atopic dermatitis was the most common disease of this group, with 489 patients (58.8%), followed by psoriasis, with 91 patients (10.9%) and lichen planus, with 31 patients (3.7%).

The second most frequent category was genodermatoses (379 patients, 14.2%). Keratinization disorders were the most common disease group (75 patients, 19.8%), followed by epidermolysis bullosa (68 patients, 17.9%), and neurofibromatosis/Legius syndrome (56 patients, 14.8%).

The third largest category was infectious diseases, with 335 patients (12.6%). Viral infections were the most common disease group, with 163 patients (48.7%), followed by the fungal infections group (82 patients, 24.5%) and ectoparasitosis (44 patients, 13.1%) (Table 1).

Prevalence of skin diseases by groups (n=2668).

| Groups of diseases | Frequency (n) | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Inflammatory diseases | 832 | 31.2 |

| - Atopic dermatitis | 489 | 58.8 |

| - Psoriasis | 91 | 10.9 |

| - Lichen planus | 31 | 3.7 |

| - Contact dermatitis | 25 | 3.0 |

| - Othersa | 196 | 23.6 |

| Genodermatoses | 379 | 14.2 |

| - Keratinization disorders | 75 | 19.8 |

| - Epidermolysis bullosa | 68 | 17.9 |

| - Neurofibromatosis/Legius | 56 | 14.8 |

| - Cutaneous mosaicism | 47 | 12.4 |

| - Othersb | 133 | 35.1 |

| Infectious diseases | 335 | 12.6 |

| - Viral infections | 163 | 48.7 |

| - Fungal infections | 82 | 24.5 |

| - Ectoparasitosis | 44 | 13.1 |

| - Bacterial infections | 42 | 12.5 |

| - Protozoal infections | 4 | 1.2 |

| Adnexal disorders | 334 | 12.5 |

| - Acne vulgaris | 133 | 39.8 |

| - Alopecia areata | 54 | 16.2 |

| - Onychocryptosis | 30 | 9.0 |

| - Hyperhidrosis | 11 | 3.3 |

| - Othersc | 106 | 31.7 |

| Cysts and neoplasms | 285 | 10.7 |

| - Melanocytic nevi | 108 | 37.9 |

| - Epidermal nevi | 43 | 15.1 |

| - Proliferation and tumors of connective/muscular/neural/adipose tissues | 31 | 10.9 |

| - Mastocytosis | 27 | 9.5 |

| - Othersd | 76 | 26.7 |

| Vascular disorders | 187 | 7.0 |

| - Infantile hemangioma | 105 | 56.1 |

| - Vascular malformations | 44 | 23.5 |

| - Pyogenic granuloma | 16 | 8.6 |

| - Syndrome-related vascular malformations | 12 | 6.4 |

| - Otherse | 10 | 5.3 |

| Connective tissue disorders | 91 | 3.4 |

| - Scleroderma | 65 | 71.4 |

| - Lupus erythematosus | 15 | 16.5 |

| - Dermatomyositis | 9 | 9.9 |

| - Othersf | 2 | 2.2 |

| Pigmentary disorders | 86 | 3.2 |

| - Vitiligo | 81 | 94.2 |

| - Postinflammatory dyschromia | 2 | 2.3 |

| - Melasma | 3 | 3.5 |

| Purpura and vasculitis | 22 | 0.8 |

| - Figurate purpura | 7 | 31.8 |

| - Leukocytoclastic vasculitis | 5 | 22.7 |

| - Henoch-Schonlein purpura | 2 | 9.1 |

| - Behcet disease | 2 | 9.1 |

| - Othersg | 6 | 27.3 |

| Drug reactions | 21 | 0.8 |

| - Fixed drug eruption | 9 | 42.9 |

| - Erythema multiforme | 5 | 23.8 |

| - Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis spectrum | 4 | 19.0 |

| - DRESS syndrome (drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms) | 1 | 4.8 |

| - Othersh | 2 | 9.5 |

| Autoimmune bullous diseases | 16 | 0.6 |

| - Linear IgA bullous dermatosis | 6 | 37.5 |

| - Pemphigus foliaceus | 3 | 18.7 |

| - Pemphigus vulgaris | 3 | 18.7 |

| - Bullous pemphigoid | 2 | 12.6 |

| - Othersi | 2 | 12.6 |

| Others | 23 | 0.9 |

| - Othersj | 23 | 100 |

| Under investigation | 56 | 2.1 |

| - Under investigation | 56 | 100 |

The frequencies in italic are related to the prevalence of skin diseases by groups and the frequencies not in italic correspond to the frequency in each group.

Included eczematous dermatitis, seborrheic dermatitis, pityriasis rosea, urticaria, granuloma annulare, pityriasis lichenoides chronica, pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta, strophulus, lichen striatus, lichen nitidus, pityriasis alba, graft-vs.-host disease, and panniculitis.

Included ectodermal dysplasia, tuberous sclerosis, genodermatoses with acromia, genodermatoses with high potential for developing neoplasms, and primary immunodeficiencies.

Included hidradenitis suppurativa, acneiform eruptions, perioral dermatitis, folliculitis decalvans, folliculitis scalp, acne keloidalis nuchae, rosacea, keratosis pilaris, androgenetic alopecia, congenital alopecia, traction alopecia, telogen effluvium, subungual exostosis, melanonychia striata, paronychia, miliaria, hematidrosis, and bromhidrosis.

Considering the frequency of dermatoses by age group, the most three common skin diseases were, respectively: in infants, infantile hemangioma (28.8%), scabies (11.9%), and atopic dermatitis (8.5%); in toddlers, infantile hemangioma (20.2%), atopic dermatitis (15.3%), and scabies (7.6%); in preschoolers, atopic dermatitis (17.0%), infantile hemangioma (8.1%), and molluscum contagiosum (6.1%); in schoolchildren, atopic dermatitis (24.5%), molluscum contagiosum (5.8%), and psoriasis (4.1%); in adolescents, atopic dermatitis (19.8%), acne vulgaris (10.4%), and psoriasis (4.8%).

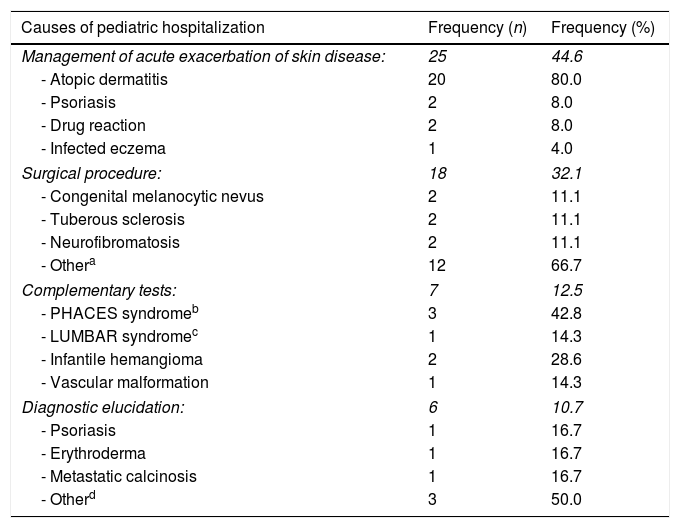

HospitalizationDuring the one-year period, 56 patients were admitted to the Dermatology Division ward. The main reason for admission was management of acute exacerbation of the skin disease, mainly atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, and drug reactions in 25 cases (44.6%). Eighteen patients (32.1%) were admitted for surgical procedures, due to conditions like congenital melanocytic nevus, tuberous sclerosis, and neurofibromatosis. Seven patients (12.5%) were admitted for complementary testing, mostly due to suspected PHACES syndrome (posterior fossa malformations, hemangioma, arterial anomalies, coarctation of the aorta/cardiac defects, eye abnormalities, and malformations of the sternal cleft, supraumbilical raphe, or both). Six patients (10.7%) were admitted for diagnostic elucidation (Table 2).

Prevalence and causes of pediatric hospitalization in the study period (n=56).

| Causes of pediatric hospitalization | Frequency (n) | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Management of acute exacerbation of skin disease: | 25 | 44.6 |

| - Atopic dermatitis | 20 | 80.0 |

| - Psoriasis | 2 | 8.0 |

| - Drug reaction | 2 | 8.0 |

| - Infected eczema | 1 | 4.0 |

| Surgical procedure: | 18 | 32.1 |

| - Congenital melanocytic nevus | 2 | 11.1 |

| - Tuberous sclerosis | 2 | 11.1 |

| - Neurofibromatosis | 2 | 11.1 |

| - Othera | 12 | 66.7 |

| Complementary tests: | 7 | 12.5 |

| - PHACES syndromeb | 3 | 42.8 |

| - LUMBAR syndromec | 1 | 14.3 |

| - Infantile hemangioma | 2 | 28.6 |

| - Vascular malformation | 1 | 14.3 |

| Diagnostic elucidation: | 6 | 10.7 |

| - Psoriasis | 1 | 16.7 |

| - Erythroderma | 1 | 16.7 |

| - Metastatic calcinosis | 1 | 16.7 |

| - Otherd | 3 | 50.0 |

The frequencies in italic are related to the groups of causes of pediatric hospitalization and the frequencies not in italic correspond to the frequency in each group.

Included angiokeratoma, scleroderma, warts, ungual lichen planus, Rothmund–Thomson syndrome, ungual melanoma, molluscum contagiosum, epidermal cysts, onychocryptosis, nevus verrucosus, and pilomatricoma.

PHACES syndrome: posterior fossa brain malformations, hemangioma, arterial lesions, cardiac abnormalities, eye abnormalities, and malformations of the sternal cleft, supraumbilical raphe, or both.

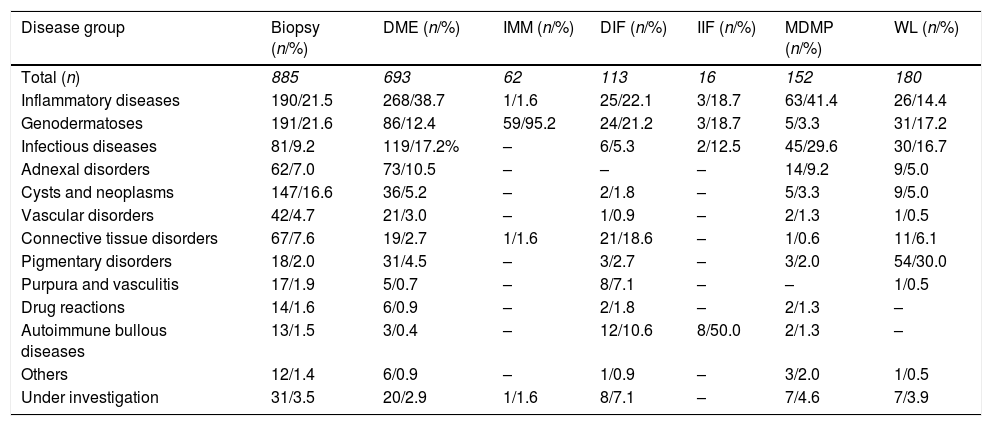

Considering the demand of complementary testing, 885 skin biopsies were performed and the leading group was genodermatoses (21.6%). There were 693 direct mycological examinations performed, with a higher demand in the inflammatory diseases group (38.7%; Table 3).

Complementary diagnostic exams by disease group.

| Disease group | Biopsy (n/%) | DME (n/%) | IMM (n/%) | DIF (n/%) | IIF (n/%) | MDMP (n/%) | WL (n/%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n) | 885 | 693 | 62 | 113 | 16 | 152 | 180 |

| Inflammatory diseases | 190/21.5 | 268/38.7 | 1/1.6 | 25/22.1 | 3/18.7 | 63/41.4 | 26/14.4 |

| Genodermatoses | 191/21.6 | 86/12.4 | 59/95.2 | 24/21.2 | 3/18.7 | 5/3.3 | 31/17.2 |

| Infectious diseases | 81/9.2 | 119/17.2% | – | 6/5.3 | 2/12.5 | 45/29.6 | 30/16.7 |

| Adnexal disorders | 62/7.0 | 73/10.5 | – | – | – | 14/9.2 | 9/5.0 |

| Cysts and neoplasms | 147/16.6 | 36/5.2 | – | 2/1.8 | – | 5/3.3 | 9/5.0 |

| Vascular disorders | 42/4.7 | 21/3.0 | – | 1/0.9 | – | 2/1.3 | 1/0.5 |

| Connective tissue disorders | 67/7.6 | 19/2.7 | 1/1.6 | 21/18.6 | – | 1/0.6 | 11/6.1 |

| Pigmentary disorders | 18/2.0 | 31/4.5 | – | 3/2.7 | – | 3/2.0 | 54/30.0 |

| Purpura and vasculitis | 17/1.9 | 5/0.7 | – | 8/7.1 | – | – | 1/0.5 |

| Drug reactions | 14/1.6 | 6/0.9 | – | 2/1.8 | – | 2/1.3 | – |

| Autoimmune bullous diseases | 13/1.5 | 3/0.4 | – | 12/10.6 | 8/50.0 | 2/1.3 | – |

| Others | 12/1.4 | 6/0.9 | – | 1/0.9 | – | 3/2.0 | 1/0.5 |

| Under investigation | 31/3.5 | 20/2.9 | 1/1.6 | 8/7.1 | – | 7/4.6 | 7/3.9 |

Percentages were calculated according to the number of exams performed by group of disease.

DME, direct mycological examination; IMM, immunological mapping; DIF, direct immunofluorescence; IIF, indirect immunofluorescence; MDMP, microscopy detection of parasites; WL, Wood's light.

In the casuistry, 1579 patients (67.8%) had exclusive follow-up within the Dermatology Division. The other 751 patients (32.2%) required multidisciplinary care. In the latter group, 30.6% of the patients followed up by other specialties presented with some genodermatosis. Inflammatory diseases and adnexal disorders corresponded to 26.9% and 12.9% of the cases, respectively. The most common specialties were as follows: ophthalmology (278 patients, 37.0%), otorhinolaryngology (180 patients, 24.0%), neurology (141 patients, 18.8%), and psychology (134 patients, 17.8%).

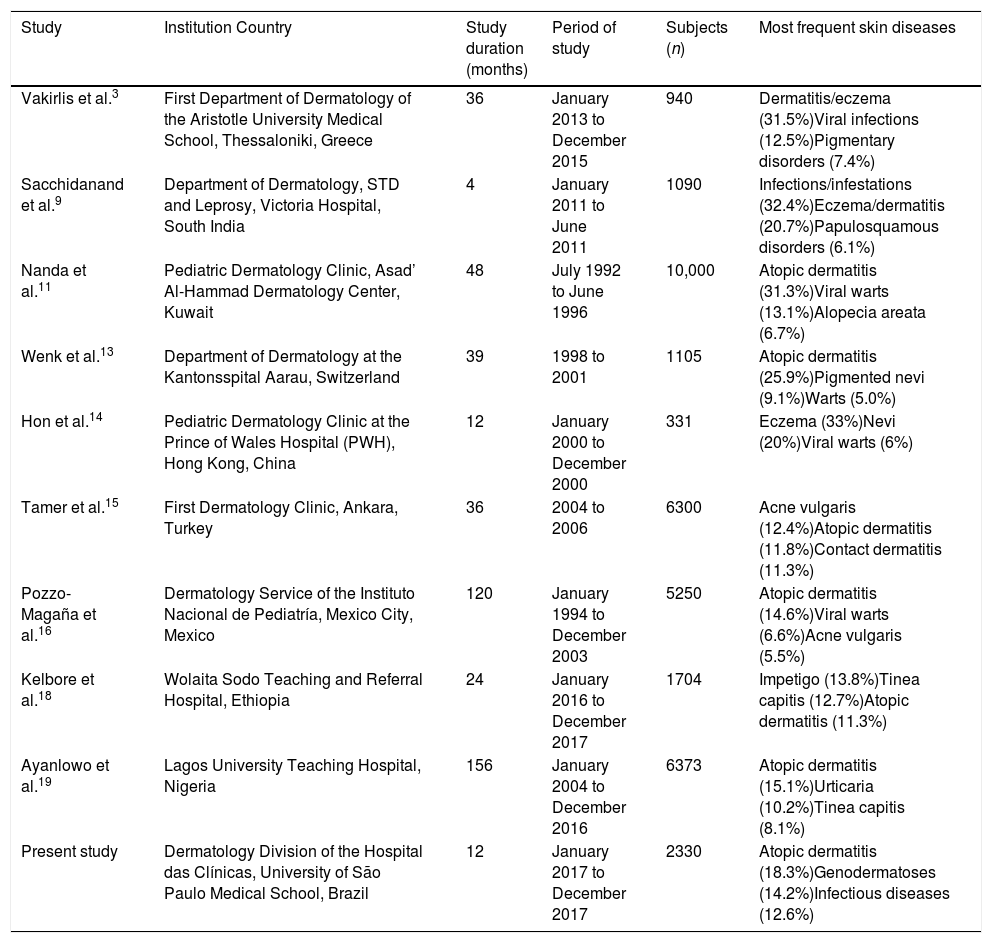

DiscussionThe most common disease among pediatric population in this study was atopic dermatitis (AD), corresponding to 489 cases (18.3%). This result was similar to that observed in other studies and highlights the fact that AD is a major public health problem worldwide3,11,13,14,16,18,19 (Table 4). AD was also the main cause of hospitalization, probably because this service is a referral center and many of the AD patients present with severe disease. A multicentric epidemiologic study conducted in Japan20 with 17,842 patients of all age groups also presented atopic dermatitis as the main diagnosis, not only in the pediatric population but also in the adults up to the age of 40 years. Over this age range, the importance of other eczematous diseases and dermatophytosis rises.

Literature review: comparison with similar studies.

| Study | Institution Country | Study duration (months) | Period of study | Subjects (n) | Most frequent skin diseases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vakirlis et al.3 | First Department of Dermatology of the Aristotle University Medical School, Thessaloniki, Greece | 36 | January 2013 to December 2015 | 940 | Dermatitis/eczema (31.5%)Viral infections (12.5%)Pigmentary disorders (7.4%) |

| Sacchidanand et al.9 | Department of Dermatology, STD and Leprosy, Victoria Hospital, South India | 4 | January 2011 to June 2011 | 1090 | Infections/infestations (32.4%)Eczema/dermatitis (20.7%)Papulosquamous disorders (6.1%) |

| Nanda et al.11 | Pediatric Dermatology Clinic, Asad’ Al-Hammad Dermatology Center, Kuwait | 48 | July 1992 to June 1996 | 10,000 | Atopic dermatitis (31.3%)Viral warts (13.1%)Alopecia areata (6.7%) |

| Wenk et al.13 | Department of Dermatology at the Kantonsspital Aarau, Switzerland | 39 | 1998 to 2001 | 1105 | Atopic dermatitis (25.9%)Pigmented nevi (9.1%)Warts (5.0%) |

| Hon et al.14 | Pediatric Dermatology Clinic at the Prince of Wales Hospital (PWH), Hong Kong, China | 12 | January 2000 to December 2000 | 331 | Eczema (33%)Nevi (20%)Viral warts (6%) |

| Tamer et al.15 | First Dermatology Clinic, Ankara, Turkey | 36 | 2004 to 2006 | 6300 | Acne vulgaris (12.4%)Atopic dermatitis (11.8%)Contact dermatitis (11.3%) |

| Pozzo-Magaña et al.16 | Dermatology Service of the Instituto Nacional de Pediatría, Mexico City, Mexico | 120 | January 1994 to December 2003 | 5250 | Atopic dermatitis (14.6%)Viral warts (6.6%)Acne vulgaris (5.5%) |

| Kelbore et al.18 | Wolaita Sodo Teaching and Referral Hospital, Ethiopia | 24 | January 2016 to December 2017 | 1704 | Impetigo (13.8%)Tinea capitis (12.7%)Atopic dermatitis (11.3%) |

| Ayanlowo et al.19 | Lagos University Teaching Hospital, Nigeria | 156 | January 2004 to December 2016 | 6373 | Atopic dermatitis (15.1%)Urticaria (10.2%)Tinea capitis (8.1%) |

| Present study | Dermatology Division of the Hospital das Clínicas, University of São Paulo Medical School, Brazil | 12 | January 2017 to December 2017 | 2330 | Atopic dermatitis (18.3%)Genodermatoses (14.2%)Infectious diseases (12.6%) |

Another study performed in Brazil21 analyzed data from 9629 patients from all age groups classified as it follows: 0–12 years, 12–24 years, 25–59 years, and 60 years and older, with a total of 13,293 diagnoses. The mean age was 42.8 years. The most frequent diagnoses by groups were: atopic dermatitis, molluscum contagiosum, and viral warts (0–12 years); acne, contact dermatitis, and atopic dermatitis (12–24 years), photoaging, melasma, and psoriasis (25–59 years); nonmelanoma skin cancer, actinic keratosis, and photoaging (60 years and older). The present study included patients aged up to 18 years old, and considering only the group of patients between 0 and 12 years (1351 patients), the most frequent diagnoses were: atopic dermatitis (277 patients, 20.5%), infantile hemangioma (78 patients, 0.6%), and molluscum contagiosum (69 patients, 0.5%). These findings emphasize the difference between age groups and the importance of adequate health services accordingly to the epidemiologic profile.

A high prevalence of rare diseases – such as genodermatoses, autoimmune bullous diseases, and mastocytosis – was observed in this study. Keratinization disorders were the most frequent among the genetic skin diseases group, with 75 patients (2.8%), including ichthyosis, erythrokeratodermia, Darier disease, peeling skin syndrome, and pachyonychia congenita. The second most frequent diagnosis in this group was congenital epidermolysis bullosa, with 68 patients (2.5%). These results can be justified by the fact that HC-FMUSP is a reference center in Brazil, with a specialized pediatric dermatology staff and equipped with complementary tools necessary for the diagnosis and follow-up.

Genodermatoses with high potential for developing neoplasms, although corresponding to only 21 cases (0.8%), are relevant due to their rarity. Those included xeroderma pigmentosum (nine cases), Gorlin-Goltz syndrome (five cases), Rothmund-Thomson syndrome (five cases) and dyskeratosis congenita (two cases). Similar studies conducted did not report these findings3,9,11–20 (Table 4). The estimated incidence of xeroderma pigmentosum and Gorlin-Goltz syndrome is 1:20,000–1,000,000 and 1:50,000–150,000, respectively, with significant variation among countries.22,23 Epidemiologic data for dyskeratosis congenita and Rothmund-Thomson is also scarce.

Another interesting result is the number of patients with the diagnoses of infantile hemangioma (105 cases, 3.9%), scleroderma (65 cases, 2.4%), and autoimmune bullous diseases (16 cases, 0.6%). The authors probably did not observe a high frequency of common diseases in pediatric population – such as infectious diseases (e.g., impetigo, viral warts, herpes simplex), hyperhidrosis, and alopecia areata – because these cases were not referred to HC-FMUSP (a tertiary hospital) and were probably treated at the primary care units. Also, this service is a referral center for the treatment of infantile hemangiomas and most of the referred cases are followed up at the dermatologic clinic. Studies performed in Greece, Mexico, and Turkey showed a lower frequency of infantile hemangioma (2.9%, 2.3%, and 0.3%, respectively) than the present study.3,9,11–21

Considering this study's results on neurofibromatosis and Legius syndrome, a low number of cases (56 cases, 14.8%) was observed in the casuistry, despite of the high prevalence of neurofibromatosis in the general population. The dermatologic clinic follows up some patients and some of them are followed up by other specialties, such as neurology and orthopedics, and they are referred to the clinic only when it is needed. Also, patients with less severe disease are followed up at primary health care units.

This service has a specialized dermatology ward, and in the period of one year under study, 56 patients under 18 years old were admitted. The main cause of hospitalization was atopic dermatitis (35.7%), followed by patients admitted for surgical procedures (32.1%) and additional imaging examination (12.5%). A survey conducted in the United States24 analyzed the pattern of dermatology inpatients over a period of two years in the pediatric population, with a total of 108 admissions and a mean age of 5.8 years. The most common diagnoses were atopic dermatitis (86.1%), psoriasis (3.7%), and eczema herpeticum (2.8%). In another study performed in the United States,25 dermatologic diseases were responsible for 4.2% of all admissions in a pediatric ward, and infectious diseases were the leading cause. Dermatology is based primarily on outpatient treatment, but hospital admission may be needed and plays a substantial role in some skin disorders. Considering severe atopic dermatitis, hospitalization not only addresses treatment of the illness, but also focuses on education of the family.24,26,27

Considering the need for complementary testing, a large number of diseases can be clinically diagnosed, but skin biopsies and direct mycological examination have arisen as important diagnostic tools. There were 885 biopsies performed, totalling 38.0% of the subjects. The most demanding disease group was genodermatoses, with 191 biopsies in 379 subjects (50.4%). A survey conducted in China14 showed a lower rate of skin biopsy conducted in the pediatric age group (6.9%). In that study, most skin conditions were diagnosed clinically.

In the present study, many patients needed a multidisciplinary follow-up. This could be explained by the large number of complex cases followed-up, such as patients with genetic and autoimmune bullous diseases. This data was not addressed by similar studies3,9,11–20 (Table 4).

The different prevalence of some skin diseases among studies may be influenced by local particularities such as socioeconomic, cultural, and climatic conditions. The present study's casuistry is unique as the clinic is a referral center for a huge region, including patients that come from other countries, usually from South America, seeking specialized dermatological care.

Dermatologic disorders are very common in the pediatric age group and are not only addressed by the specialist, but also by pediatricians and family physicians. The casuistry highlights the role of a tertiary hospital in the health system, capable of managing common diseases, such as atopic dermatitis, but also focused on patients with rare pediatric dermatoses. Due to the high frequency of pediatric skin diseases, it is important to establish a specialized, multidisciplinary team in referral centers. Finally, epidemiological data are necessary and useful to better plan healthcare strategies, including allocation of resources and preventive measures.1,2

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.