To analyze the available evidence regarding the efficacy of interventions on parents whose children were aged 2–5 years to promote parental competence and skills for children's healthy lifestyles.

SourceArticles published in English and Spanish, available at PubMed, Psycinfo, CINAHL, Web of Science, Eric, and Cochrane Library were reviewed.

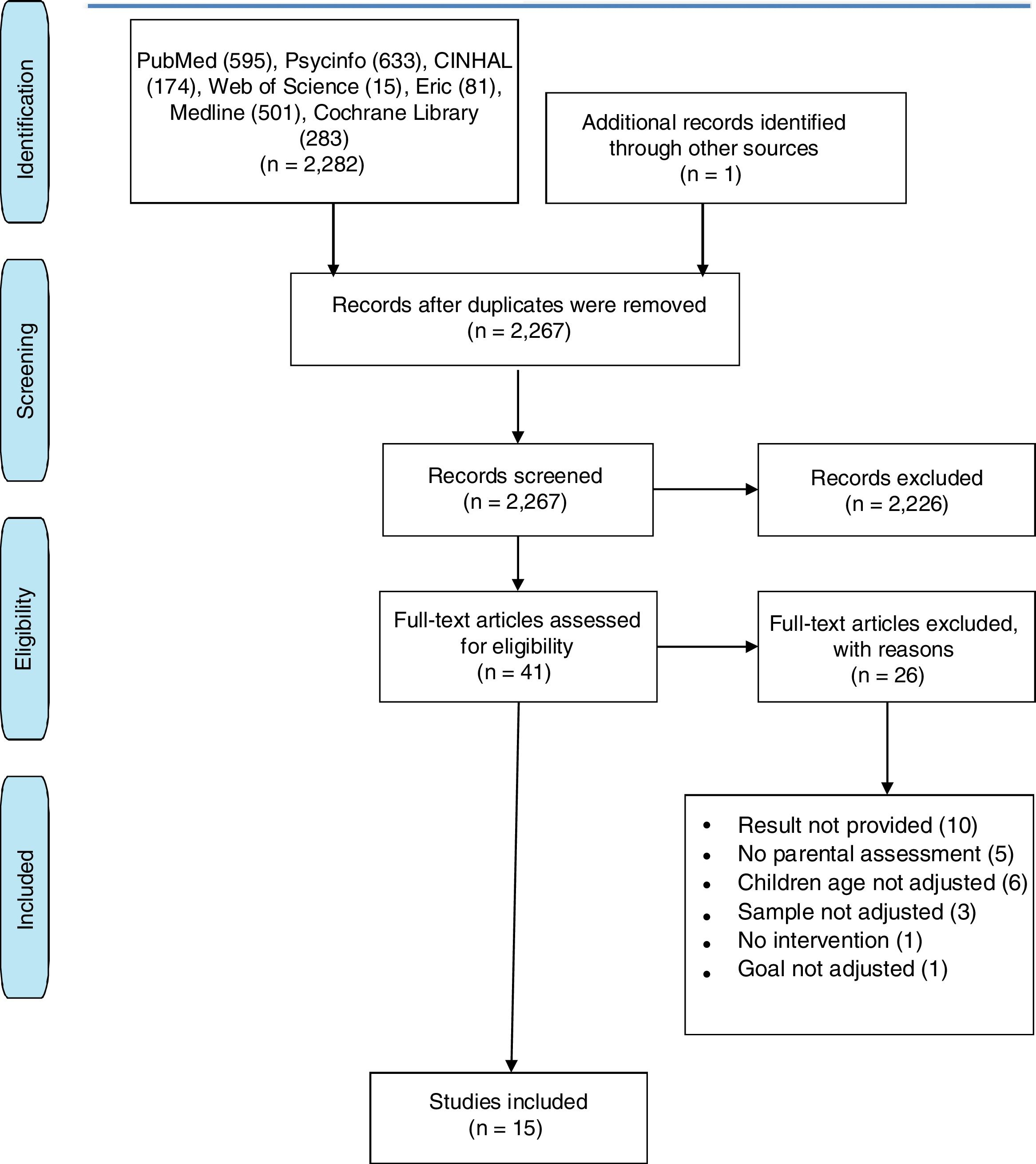

Summary of the findingsThe literature search yielded 2282 articles. Forty-one full texts were retrieved and assessed for inclusion using the PRISMA flow diagram. Twenty-six articles were excluded, as they did not meet the inclusion criteria. In the end, 15 studies were included. The studies were conducted between 2003 and 2016, nine in North America, four in Europe, and two in Asia. Extracted data were synthesized in a tabular format. CASPe guide was used to assess the quality of studies that was moderate overall. Parental self-efficacy was the main construct assessed in most studies. Four studies reported an increase in parental self-efficacy, although most of them were studies without control groups.

ConclusionsOutcomes of interventions to improve parental competence in order to promote children's lifestyles are promising, but inconsistent. Additional studies with higher methodological and conceptual quality are needed.

Analisar as evidências disponíveis com relação à eficácia de intervenções em pais de filhos com idade entre 2 e 5 anos para promover a competência e as habilidades dos pais a respeito de estilos de vida saudáveis para as crianças.

FonteForam analisados artigos publicados em PubMed, Psycinfo, CINAHL, Web of Science, Eric e Biblioteca Cochrane. Inglês e espanhol.

Resumo dos achadosA pesquisa da literatura encontrou 2282 artigos. 41 textos completos foram selecionados e avaliados para inclusão utilizando o fluxograma PRISMA. 26 artigos foram excluídos, pois não atendiam aos critérios de inclusão. Por fim, 15 estudos foram incluídos. Os estudos foram realizados entre 2003 e 2016. Nove estudos foram conduzidos na América do Norte, quatro eram de origem europeia e dois de origem asiática. Os dados extraídos foram sintetizados em formato de tabela. O guia CASPe foi utilizado para avaliar a qualidade dos estudos, que, em geral, foi moderada. A autoeficácia dos pais foi o principal dado avaliado na maioria dos estudos. Quatro estudos relataram um aumento na autoeficácia dos pais, apesar de que a maioria eram estudos sem grupo de controle.

ConclusõesOs resultados de intervenções para melhorar a competência dos pais para promover os estilos de vida das crianças são promissores, porém incoerentes. São necessários estudos adicionais com melhor qualidade metodológica e conceitual.

Childhood health promotion that fosters the adoption of attitudes and healthy lifestyles might be considered one of the most cost-effective interventions, given the potential impact throughout the life course of individuals.1,2 Child development is crucial between 2 and 5 years, as this stage is characterized by emotional, social, cognitive, language, and motor skills development. Early childhood is therefore the best time to carry out activities that promote the acquisition of healthy lifestyles.3,4 This period in children's development has a peculiarity; parents play a vital role in providing their children a positive environment and atmosphere to ensure a healthy development and lifestyle. Therefore, parents represent a key target if children's health is to be promoted.5–7

Identifying the underlying mechanisms through which parents exert healthy parenting is key to developing effective interventions. Parenting is influenced by multiple determinants including personal resources of parents, child's characteristics, and social sources of stress and support.8 The interaction between this amalgam of factors modulates parental competence, which has been defined as the feelings, abilities, and skills that parents have in raising their children.9,10 Depending on the development of this parental competence, parents will be able to promote healthy lifestyles in their children.9–12

There is evidence suggesting the need to help parents in promoting healthy lifestyles among their children within a positive parenting framework.13–16 The aim of this systematic review was to explore the available evidence on intervention studies directed at parents whose children were aged 2–5 years to promote parental competence and skills for children's healthy lifestyles. This review also set out to specifically assess the interventions and the underlying mechanisms in detail, as well as to explore their impact.

MethodsData sourcesSearches were conducted in a number of databases, including PubMed, Psycinfo, Cinhal, Web of Science, Eric, and the Cochrane Library. Search terms encompassed terms related to parental competence and intervention strategies. These included: parenting, parental competence, positive parenting, parenting practices, strategies, intervention, programme, program, treatment, and health promotion. All terms were combined with the Boolean operators AND and OR. The interventions considered in this review were those carried out more on an individual level than on a health policy level. No attempt was made to search for unpublished works, such as dissertations and theses, neither limits were established in relation to the year of publication. Articles in English and Spanish were reviewed.

Inclusion and exclusion criteriaThis review focused on intervention studies that sought to increase the development of parental competence or any of the abilities that parents need in order to promote healthy lifestyles among their children.9 For this purpose, studies were included in the review if they met the inclusion criteria. These were established according to the different characteristics shown below.

Type of participants- •

Mothers or fathers (or both) whose children were aged between 2 and 5 years old.

- •

Educational, motivational, training, or informational approach targeting parental competence or skills.

- •

Main focus should be parents, regardless of whether the intervention also involved participation of children and/or teachers.

- •

Interventions conducted in childhood-relevant contexts such as home, school, healthcare services, or community.

- •

Studies should assess parental competence or skills in at least one of its two forms (objective or subjective) before and after the intervention.11

As for the exclusion criteria, studies were rejected if they were not intervention studies; did not provide results in terms of parental competence; included parents of children not aged between 2 and 5 years; or were exclusively directed to parents of teenagers or children with chronic illnesses, as it was most likely that these features could impact on the development of the intervention.

Data extraction and data synthesisInitial screening was undertaken to identify potential articles meeting the inclusion criteria from the titles and abstracts. Full texts were obtained for the relevant articles. Full texts were also obtained for any study whose inclusion was unclear. All articles were examined to ensure that they met all the inclusion criteria. Any uncertainties were resolved by discussion. PRISMA flow diagram procedure was used to ensure rigor in the selection process.17

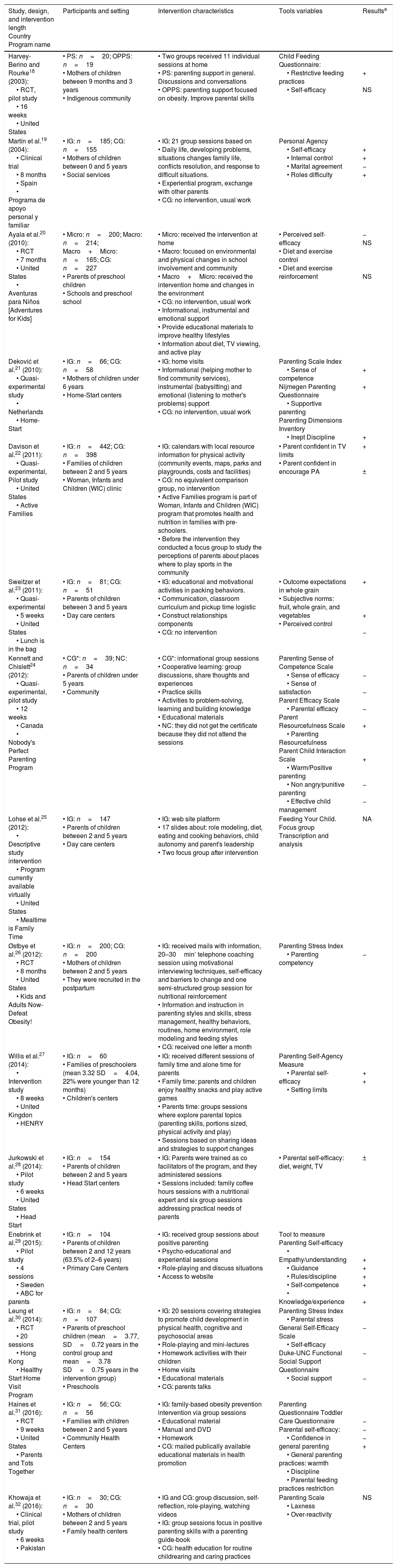

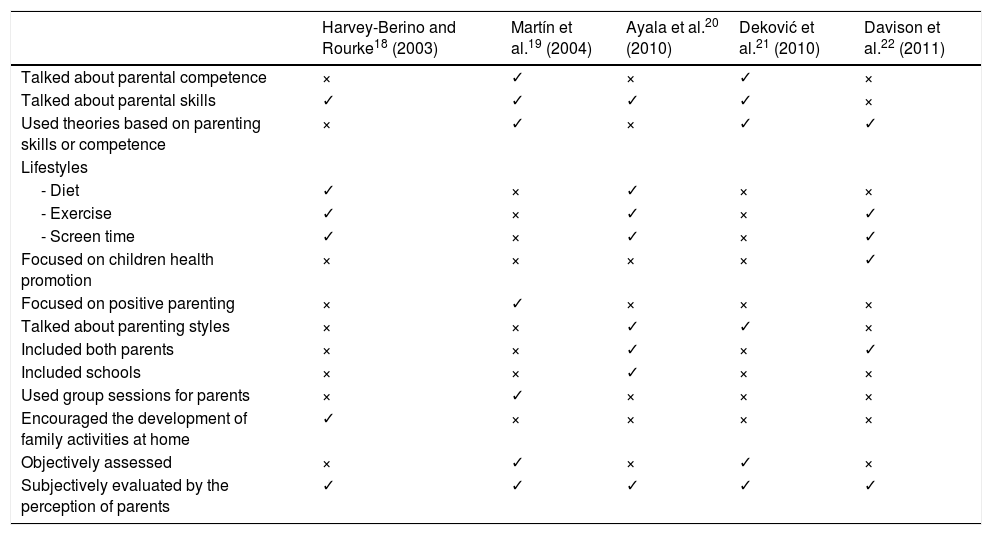

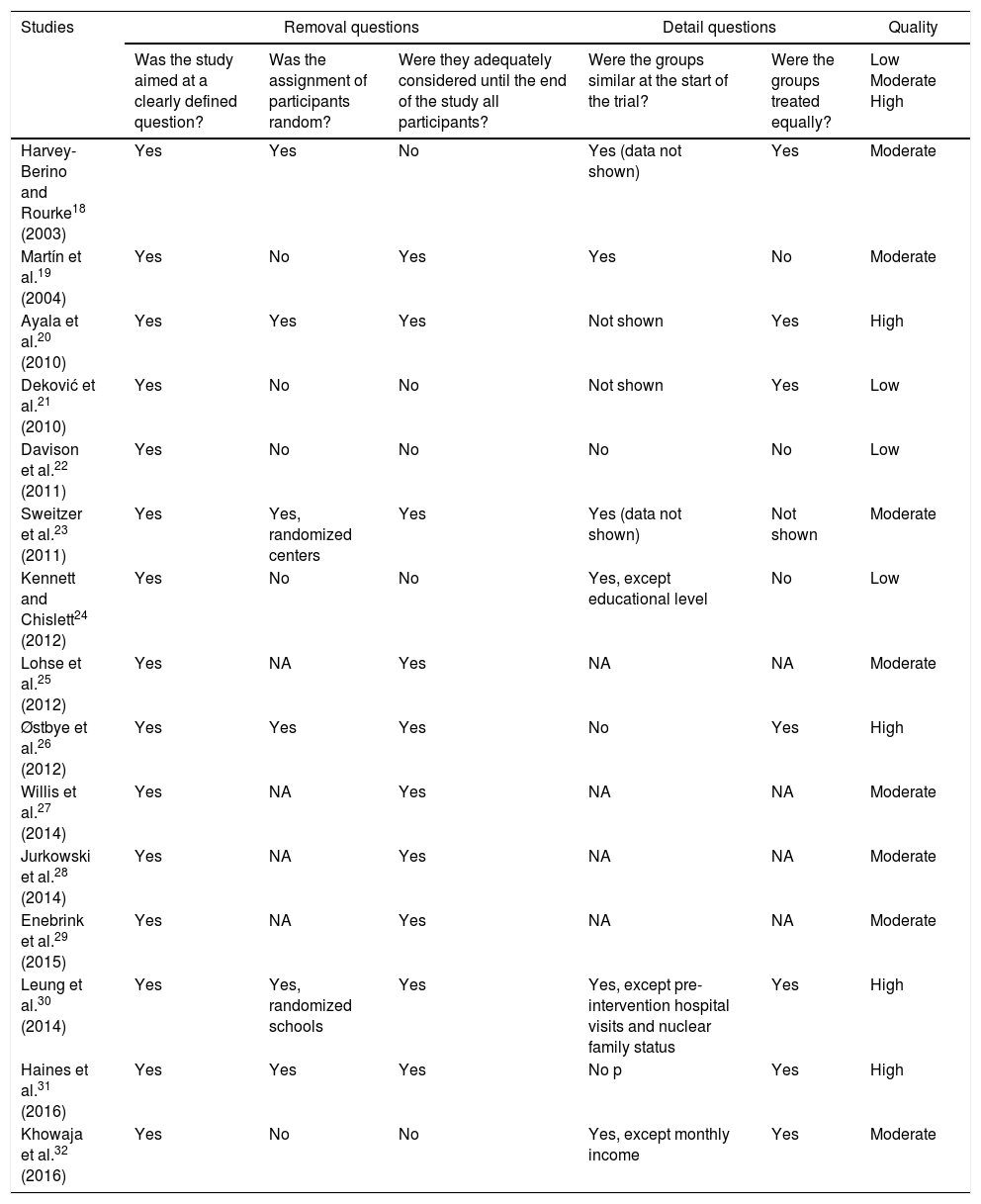

In order to analyze and synthesize the data from the fifteen studies included,18–32 three tables were used. Table 1 provides general information of the studies including author, year of publication, country and name of the program, design, participants and context in which the program took place, the main characteristics of intervention, length, measurement tools, variables, and main results. Quality assessment was considered a key feature for this review and encompassed two components: the adequacy of the interventions in terms of the key components that a parental competence intervention should have and the methodological quality of the studies. Regarding the key components of interventions, the authors assessed whether the articles provided sufficient details about parental competence or skills and the theoretical framework used; included an objective and subjective evaluation of the competence; focused on health promotion and positive parenting; included both parents and childhood-relevant contexts; included group sessions with parents; and encouraged the development of family activities at home (Table 2). For methodological quality assessment, an adaptation of the CASPe guide33 was used (Table 3).

General description of the studies.

| Study, design, and intervention length Country Program name | Participants and setting | Intervention characteristics | Tools variables | Resultsa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harvey-Berino and Rourke18 (2003): • RCT, pilot study • 16 weeks • United States | • PS: n=20; OPPS: n=19 • Mothers of children between 9 months and 3 years • Indigenous community | • Two groups received 11 individual sessions at home • PS: parenting support in general. Discussions and conversations • OPPS: parenting support focused on obesity. Improve parental skills | Child Feeding Questionnaire: • Restrictive feeding practices • Self-efficacy | + NS |

| Martín et al.19 (2004): • Clinical trial • 8 months • Spain • Programa de apoyo personal y familiar | • IG: n=185; CG: n=155 • Mothers of children between 0 and 5 years • Social services | • IG: 21 group sessions based on • Daily life, developing problems, situations changes family life, conflicts resolution, and response to difficult situations. • Experiential program, exchange with other parents • CG: no intervention, usual work | Personal Agency • Self-efficacy • Internal control • Marital agreement • Roles difficulty | + + − + |

| Ayala et al.20 (2010): • RCT • 7 months • United States • Aventuras para Niños [Adventures for Kids] | • Micro: n=200; Macro: n=214; Macro+Micro: n=165; CG: n=227 • Parents of preschool children • Schools and preschool school | • Micro: received the intervention at home • Macro: focused on environmental and physical changes in school involvement and community • Macro+Micro: received the intervention home and changes in the environment • CG: no intervention, usual work • Informational, instrumental and emotional support • Provide educational materials to improve healthy lifestyles • Information about diet, TV viewing, and active play | • Perceived self-efficacy • Diet and exercise control • Diet and exercise reinforcement | − NS NS |

| Deković et al.21 (2010): • Quasi-experimental study • Netherlands • Home-Start | • IG: n=66; CG: n=58 • Mothers of children under 6 years • Home-Start centers | • IG: home visits • Informational (helping mother to find community services), instrumental (babysitting) and emotional (listening to mother's problems) support • CG: no intervention, usual work | Parenting Scale Index • Sense of competence Nijmegen Parenting Questionnaire • Supportive parenting Parenting Dimensions Inventory • Inept Discipline | + + + |

| Davison et al.22 (2011): • Quasi-experimental, Pilot study • United States • Active Families | • IG: n=442; CG: n=398 • Families of children between 2 and 5 years • Woman, Infants and Children (WIC) clinic | • IG: calendars with local resource information for physical activity (community events, maps, parks and playgrounds, costs and facilities) • CG: no equivalent comparison group, no intervention • Active Families program is part of Woman, Infants and Children (WIC) program that promotes health and nutrition in families with pre-schoolers. • Before the intervention they conducted a focus group to study the perceptions of parents about places where to play sports in the community | • Parent confident in TV limits • Parent confident in encourage PA | + ± |

| Sweitzer et al.23 (2011): • Quasi-experimental • 5 weeks • United States • Lunch is in the bag | • IG: n=81; CG: n=51 • Parents of children between 3 and 5 years • Day care centers | • IG: educational and motivational activities in packing behaviors. • Communication, classroom curriculum and pickup time logistic • Construct relationships components • CG: no intervention | • Outcome expectations in whole grain • Subjective norms: fruit, whole grain, and vegetables • Perceived control | + + − |

| Kennett and Chislett24 (2012): • Quasi-experimental, pilot study • 12 weeks • Canada • Nobody's Perfect Parenting Program | • CG*: n=39; NC: n=34 • Parents of children under 5 years • Community | • CG*: informational group sessions • Cooperative learning: group discussions, share thoughts and experiences • Practice skills • Activities to problem-solving, learning and building knowledge • Educational materials • NC: they did not get the certificate because they did not attend the sessions | Parenting Sense of Competence Scale • Sense of efficacy • Sense of satisfaction Parent Efficacy Scale • Parental efficacy Parent Resourcefulness Scale • Parenting Resourcefulness Parent Child Interaction Scale • Warm/Positive parenting • Non angry/punitive parenting • Effective child management | − − − + + − − |

| Lohse et al.25 (2012): • Descriptive study intervention • Program currently available virtually • United States • Mealtime is Family Time | • IG: n=147 • Parents of children between 2 and 5 years • Day care centers | • IG: web site platform • 17 slides about: role modeling, diet, eating and cooking behaviors, child autonomy and parent's leadership • Two focus group after intervention | Feeding Your Child. Focus group Transcription and analysis | NA |

| Østbye et al.26 (2012): • RCT • 8 months • United States • Kids and Adults Now- Defeat Obesity! | • IG: n=200; CG: n=200 • Mothers of children between 2 and 5 years • They were recruited in the postpartum | • IG: received mails with information, 20–30min’ telephone coaching session using motivational interviewing techniques, self-efficacy and barriers to change and one semi-structured group session for nutritional reinforcement • Information and instruction in parenting styles and skills, stress management, healthy behaviors, routines, home environment, role modeling and feeding styles • CG: received one letter a month | Parenting Stress Index • Parenting competency | − |

| Willis et al.27 (2014): • Intervention study • 8 weeks • United Kingdon • HENRY | • IG: n=60 • Families of preschoolers (mean 3.32 SD=4.04, 22% were younger than 12 months) • Children's centers | • IG: received different sessions of family time and alone time for parents • Family time: parents and children enjoy healthy snacks and play active games • Parents time: groups sessions where explore parental topics (parenting skills, portions sized, physical activity and play) • Sessions based on sharing ideas and strategies to support changes | Parenting Self-Agency Measure • Parental self-efficacy • Setting limits | + + |

| Jurkowski et al.28 (2014): • Pilot study • 6 weeks • United States • Head Start | • IG: n=154 • Parents of children between 2 and 5 years • Head Start centers | • IG: Parents were trained as co facilitators of the program, and they administered sessions • Sessions included: family coffee hours sessions with a nutritional expert and six group sessions addressing practical needs of parents | • Parental self-efficacy: diet, weight, TV | ± |

| Enebrink et al.29 (2015): • Pilot study • 4 sessions • Sweden • ABC for parents | • IG: n=104 • Parents of children between 2 and 12 years (63.5% of 2–6 years) • Primary Care Centers | • IG: received group sessions about positive parenting • Psycho-educational and experiential sessions • Role-playing and discuss situations • Access to website | Tool to measure Parenting Self-efficacy • Empathy/understanding • Guidance • Rules/discipline • Self-competence • Knowledge/experience | + + + + + |

| Leung et al.30 (2014): • RCT • 20 sessions • Hong Kong • Healthy Start Home Visit Program | • IG: n=84; CG: n=107 • Parents of preschool children (mean=3.77, SD=0.72 years in the control group and mean=3.78 SD=0.75 years in the intervention group) • Preschools | • IG: 20 sessions covering strategies to promote child development in physical health, cognitive and psychosocial areas • Role-playing and mini-lectures • Homework activities with their children • Home visits • Educational materials • CG: parents talks | Parenting Stress Index • Parental stress General Self-Efficacy Scale • Self-efficacy Duke-UNC Functional Social Support Questionnaire • Social support | − − − |

| Haines et al.31 (2016): • RCT • 9 weeks • United States • Parents and Tots Together | • IG: n=56; CG: n=56 • Families with children between 2 and 5 years • Community Health Centers | • IG: family-based obesity prevention intervention via group sessions • Educational material • Manual and DVD • Homework • CG: mailed publically available educational materials in health promotion | Parenting Questionnaire Toddler Care Questionnaire Parental self-efficacy: • Confidence in general parenting • General parenting practices: warmth • Discipline • Parental feeding practices restriction | − − − + |

| Khowaja et al.32 (2016): • Clinical trial, pilot study • 6 weeks • Pakistan | • IG: n=30; CG: n=30 • Mothers of children between 2 and 5 years • Family health centers | • IG and CG: group discussion, self-reflection, role-playing, watching videos • IG: group sessions focus in positive parenting skills with a parenting guide-book • CG: health education for routine childrearing and caring practices | Parenting Scale • Laxness • Over-reactivity | NS |

RCT, randomized control trial; HENRY, Health Exercise Nutrition for the Really Young; PS, parenting support group; OPPS, obesity prevention plus parenting support; IG, intervention group; CG, control group; CG*, participants who had got the certificate group; NC, participants who had not got the certificate groups; PA, physical activity.

Key components of parental competence interventions.

| Harvey-Berino and Rourke18 (2003) | Martín et al.19 (2004) | Ayala et al.20 (2010) | Deković et al.21 (2010) | Davison et al.22 (2011) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Talked about parental competence | × | ✓ | × | ✓ | × |

| Talked about parental skills | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | × |

| Used theories based on parenting skills or competence | × | ✓ | × | ✓ | ✓ |

| Lifestyles | |||||

| - Diet | ✓ | × | ✓ | × | × |

| - Exercise | ✓ | × | ✓ | × | ✓ |

| - Screen time | ✓ | × | ✓ | × | ✓ |

| Focused on children health promotion | × | × | × | × | ✓ |

| Focused on positive parenting | × | ✓ | × | × | × |

| Talked about parenting styles | × | × | ✓ | ✓ | × |

| Included both parents | × | × | ✓ | × | ✓ |

| Included schools | × | × | ✓ | × | × |

| Used group sessions for parents | × | ✓ | × | × | × |

| Encouraged the development of family activities at home | ✓ | × | × | × | × |

| Objectively assessed | × | ✓ | × | ✓ | × |

| Subjectively evaluated by the perception of parents | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Sweitzer et al.23 (2011) | Kennett and Chislett24 (2012) | Lohse et al.25 (2012) | Østbye et al.26 (2012) | Willis et al.27 (2014) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Talked about parental competence | × | × | × | × | × |

| Talked about parental skills | × | ✓ | × | × | ✓ |

| Used theories based on parenting skills or competence | ✓ | × | × | ✓ | ✓ |

| Lifestyles | |||||

| - Diet | ✓ | × | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| - Exercise | × | × | × | ✓ | ✓ |

| - Screen time | × | × | × | ✓ | × |

| Focused on children health promotion | × | × | ✓ | ✓ | × |

| Focused on positive parenting | × | × | × | × | × |

| Talked about parenting styles | × | × | × | ✓ | ✓ |

| Included both parents | × | × | × | × | × |

| Included schools | × | × | × | × | × |

| Used group sessions for parents | ✓ | ✓ | × | × | ✓ |

| Encouraged the development of family activities at home | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | × | ✓ |

| Objectively assessed | ✓ | a | a | × | × |

| Subjectively evaluated by the perception of parents | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | × | ✓ |

| Jurkowski et al.28 (2014) | Enebrink et al.29 (2015) | Leung et al.30 (2014) | Haines et al.31 (2016) | Khowaja et al.32 (2016) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Talked about parental competence | × | ✓ | × | × | × |

| Talked about parental skills | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Used theories based on parenting skills or competence | × | ✓ | × | × | × |

| Lifestyles | |||||

| - Diet | ✓ | × | ✓ | ✓ | × |

| - Exercise | ✓ | × | ✓ | ✓ | × |

| - Screen time | ✓ | × | × | × | × |

| Focused on children health promotion | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Focused on positive parenting | × | ✓ | × | × | ✓ |

| Talked about parenting styles | × | × | × | × | ✓ |

| Included both parents | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | × |

| Included schools | × | × | × | × | × |

| Used group sessions for parents | ✓ | ✓ | × | ✓ | ✓ |

| Encouraged the development of family activities at home | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Objectively assessed | × | a | × | × | × |

| Subjectively evaluated by the perception of parents | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Study quality based on the CASPe guide.

| Studies | Removal questions | Detail questions | Quality | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Was the study aimed at a clearly defined question? | Was the assignment of participants random? | Were they adequately considered until the end of the study all participants? | Were the groups similar at the start of the trial? | Were the groups treated equally? | Low Moderate High | |

| Harvey-Berino and Rourke18 (2003) | Yes | Yes | No | Yes (data not shown) | Yes | Moderate |

| Martín et al.19 (2004) | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Moderate |

| Ayala et al.20 (2010) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not shown | Yes | High |

| Deković et al.21 (2010) | Yes | No | No | Not shown | Yes | Low |

| Davison et al.22 (2011) | Yes | No | No | No | No | Low |

| Sweitzer et al.23 (2011) | Yes | Yes, randomized centers | Yes | Yes (data not shown) | Not shown | Moderate |

| Kennett and Chislett24 (2012) | Yes | No | No | Yes, except educational level | No | Low |

| Lohse et al.25 (2012) | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | NA | Moderate |

| Østbye et al.26 (2012) | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | High |

| Willis et al.27 (2014) | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | NA | Moderate |

| Jurkowski et al.28 (2014) | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | NA | Moderate |

| Enebrink et al.29 (2015) | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | NA | Moderate |

| Leung et al.30 (2014) | Yes | Yes, randomized schools | Yes | Yes, except pre-intervention hospital visits and nuclear family status | Yes | High |

| Haines et al.31 (2016) | Yes | Yes | Yes | No p | Yes | High |

| Khowaja et al.32 (2016) | Yes | No | No | Yes, except monthly income | Yes | Moderate |

NA, not applicable.

The bibliographic search yielded 2282 articles. After removing duplicates, a total of 2267 abstracts were screened. Out of these, 41 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. In the end, a total of fifteen studies met the inclusion criteria for this review. A summary of the literature identified at each stage of the search process can be found in Fig. 1. Twenty-six full-texts were rejected following the exclusion criteria.

Overview of selected papersOver half of the studies included were carried out within the last five years (Table 1). Nine studies were conducted in North America, four in Europe (Sweden, England, Spain, and the Netherlands), and two in Asia (Hong Kong and Pakistan).

Sample size was highly variable across studies, ranging from 49 to 840 participants. In most studies, the sample was composed by between 100 and 200 participants. While most focused on both parents (n=10),20,22–25,27–31 four studies18,21,26,32 only included mothers in their samples and the remaining study ended up excluding male parents from the analysis, as they only represented 6% of participants.19 Despite the inclusion of both parents, female representation was over 90% in all the studies.

One-third of the studies had a special focus on vulnerable situations: low-income families,25,28,31 disadvantaged families,30 or mothers at psychosocial risk.19

InterventionsInterventions ranged in length from five weeks to eight months, although in general they were short-termed.

Intervention settings included day care centers23; family centers22,27,28,32; community health,24,31 primary care29 or social service centers19; as well as the home.18,20,21,30 In some studies, the interventions were conducted in children's centers, which were specific centers providing support for young families in disadvantaged areas of England (Table 2).27

Seven studies had a preventive focus,18–21,23,24,27 while the remaining eight studies had a positive health promotion approach.22,25,26,28–32 Only three studies explicitly referred to positive parenting.19,29,32 Some adopted a global perspective and helped parents to develop child*raising skills. However, most of the interventions (n=10) focused on specific lifestyles: four on diet, exercise, and screen time18,20,26,28; three on diet or exercise27,30,31; one on exercise and screen time22; and two on one specific lifestyle (Table 2).23,25 The majority (n=8) used group sessions as method to implement their programs.19,23,24,27–29,31,32 Four of the studies used family sessions,18,20,21,30 and the remaining (n=3)22,25,26 based their programs on sending information primarily by email (Table 1). All but five studies included an extension component, involving activities to perform at home18,23–25,27–32 in order to practice the recommendations offered in the program (Table 2).

Study methodsStudy designs included randomized controlled trials18–20,25–32 (n=11) and quasi-experimental studies21–24 (n=4). Ten studies divided the sample into two groups,18,19,21–24,26,30–32 while one divided it into four groups.20 Almost half were pilot studies (Table 1).18,22,24,28,29,32

Parental competence assessment methods varied across studies. Most of them included a subjective evaluation component of the outcome,18–25,27–32 using a variety of scales, and three considered an objective evaluation component through observations based on guidelines.19,21,23 Another three studies reported evaluations through focus groups and recordings to assess parental satisfaction with the program and how it helped them in their parenting (Table 2).24,25,29

Parental self-efficacy was the main variable measured in 12 studies.18–22,24,27–32 A variety of scales or questionnaires was used to evaluate this variable including Parenting Self-Efficacy Scale, General Self-Efficacy Scale, Tool to Measure Parenting Self-Efficacy, Parenting Efficacy Scale, Toddler Care Questionnaire, and Parenting Self-Agency Questionnaire (Table 1).

Studies’ follow-up ranged from eight weeks to 24 months, although generally they were short-termed.

Quality assessmentQuality assessment of the studies had two dimensions: conceptual adequacy of the intervention and the methodological approach of the study. In terms of the former, as it can be seen in Table 2, only three studies referred to some theoretical grounding specifically regarding parental competence.19,21,29 Ten studies made explicit reference to parenting skills,18–21,24,27–30,32 and seven studies developed aspects such as self-efficacy, self-regulation, or parents as role model, using theories based on parenting skills or competence.19,21–23,26,27,29 Five of the included studies referred to parenting styles providing significant value to the development of an authoritative or democratic style for raising children.20,21,26,27,32 Only one study considered schools as a key setting.20 Two studies encompassed strategies to ensure the fidelity of the intervention delivered. More specifically, this was done by recording some of the group sessions in order to evaluate facilitator's adherence to the program content, or using a guide to assess whether the delivery of the sessions was correct.19,29

In terms of methodological quality (Table 3), four studies were regarded as having high quality.20,26,30,31 Eight studies were considered to have a moderate quality,18,19,23,25,27–29,32 and half of them (n=4) lacked a comparison group.25,27–29 Finally, three of them had low methodological quality.21,22,24 Both the lack of a comparison group and non-randomization of the sample were considered important limitations.

Intervention resultsThe primary endpoint was parental self-efficacy in most of the studies. As suggested by Table 1, although parental self-efficacy was targeted in 12 studies, only four considered it as outcome variables, and they all used different outcome measures.19,24,27,29 Only the study by Martín et al.19 reported a higher parental self-efficacy in the post measurement in the intervention group (5.34±0.64) compared to the baseline measurement of the control group (4.49±0.54). Seemingly, Kennett and Chislett24 reported a significant increase in the variable scores of parents who earned the certificate after intervention (post: 37.30±4.63, follow-up: 37.00±4.39). Enebrink et al.29 achieved a significant increase in the components of parental self-efficacy scores as rules and discipline (pre: 42.20±9.97; post: 45.94±8.58; and follow-up: 46.80±9.36) or empathy and understanding (pre: 49.85±7.18; post: 53.69±5.40; and follow-up: 52.41±8.22). Finally, in the fourth study, parental self-efficacy scores increased over time (baseline: 12.55±4.26; post: 14.96±2.70; and follow-up: 15.34±2.72).27

Other three studies reported a higher parental self-efficacy only related to some specific components. Two of them were related to the control of TV viewing (intervention group pre: 3.93±0.81; post: 4.05±0.8228; difference between groups in post: 3.32).22 Another study was related to the parental feeding practices restriction (intervention group post: −0.32±0.61; control group post: −0.04±0.56).31 Three studies did not find changes in parental self-efficacy20,30,31 and two did not reflect the results.18,32

Four of the studies assessed parental sense of competence.21,24,26,29 Only two of them reported significant intervention effects, those who had low and moderate quality. Deković et al.21 reported higher scores in parental sense of competence in the intervention group (0.01±0.01) when compared with the control group (0.03±0.01). The study with only one group found higher scores in parental self-competence (pre: 47.29±7.76; post: 51.02±7.11; and follow-up: 49.86±8.93).29 The other two studies did not report changes in parental self-perception of competency.24,26

DiscussionThe results of this systematic review do not provide evidence that the interventions reviewed made a significant difference in terms of enhancing parental competence for children's health promotion. Nonetheless, there are a number of issues that merit attention. In this review, there appeared to be a tendency that studies considered methodologically sound failed to find statistically significant differences in the primary outcomes. This may be partly due to the heterogeneity of the scales used, including non-validated tools. It might also be that interventions were at their early stage of development. This fact might have entailed researchers to focus on conceptual development at the expense of methodological quality, which may have resulted in them falling under the moderate-low methodological quality subgroup. Previous studies have pointed out that this is not uncommon, highlighting the difficulty in conducting such interventions where the intrinsic components of the individual firstly need to be developed and evaluated.34 This kind of interventions, which encompass several interacting components, present a number of challenges for evaluators, including practical and methodological difficulties, in accordance with the nature of complex interventions.35

Studies that evaluated parental self-efficacy provided limited details on the intervention activities. According to Bandura36,37 and other authors,38 in order to promote self-efficacy, it is necessary to consider the following four strategies: the achievements of execution, vicarious experience, verbal persuasion, and physiological states of the individual. None of the studies appeared to apply them. The lack of explanation regarding the expected mechanisms of change of the evaluated challenged ascertaining whether the marginal effect observed on parental self-efficacy was a direct consequence of the intervention. While assessing fidelity and quality of implementation, clarifying the expected mechanisms and identifying other relevant contextual factors are important aspects for developing these complex interventions; the available evidence appears to be limited in those terms.39

Furthermore, the absence of effect size estimations and the diversity in the measurements applied across the studies hinders comparison. Similarly, the lack of an adequate control group affects the internal validity of some of the studies included.40,41

Another aspect that needs to be emphasized is the limited conceptualization observed in some of the studies regarding parental competence and skills. This area of research might be considered relatively new (most of the studies included in this review were published in the last seven years), and there still appears to be a lack of consensus on which are the skills needed to be a competent parent.42 This might explain the variety in the skills addressed across the interventions. More specifically, the low theorization might imply that most studies were focused on practical skills, often limited to concrete recommendations on diet or exercise. This, in addition to hindering the adoption of a global perspective on parental functioning and its components, implies that interventions have a tendency toward an informative methodology in which parents are usually passive recipients of information.43,44 There is evidence to show that this approach does not offer the best results for the acquisition of skills and health behaviors.45,46

Secondly, several studies were based on parental self-efficacy or perceived parental competence as a key aspect of their interventions with parents. However, the aforementioned lack of conceptualization implies that parental self-efficacy and perceived competence are chosen in isolation, rather than in a set of skills or structure that identifies a group of specific skills.8 As a result, there is no clear distinction between the intervention constructs, or terms are used interchangeably. This might explain the wide variety of tools used. Moreover, most studies lack objective assessment.24,25,29 This is in accordance with previous investigations.47,48

As found in this review, research on parental competences from a health promotion perspective is currently blooming. This is timely with the growing need of supporting parents at a time when busy schedules and professional and social demands leave little space for comprehensive training on the skills needed in parenting.49 It also coincides with a high international interest in developing multi-component health promotion interventions that go beyond traditional healthy lifestyle messages, and are closer to meeting the intrinsic needs of parents, as promulgated by the European Council in the REC recommendations and the American Society for the Positive Care of children.13,50 In order to advance research in this area, a number of issues deriving from this review need to be considered in future research. More rigorous studies are needed in order to contribute to the development of effective interventions to promote parental competences. Prior to the design of large-scale evaluation studies, attention should be paid to the careful and thorough identification of conceptual models and intervention mechanisms to achieve a more comprehensive understanding of the intervention to be designed. In this process, attention should also be paid to evaluation methods. These should encompass an objective dimension, as well as focus on the use of validated scales for the subjective dimension.

ConclusionTo the best of our knowledge, this is the first review to examine health interventions focusing on parental competence to promote healthy lifestyles in children with a focus on conceptual quality. Having identified parental self-efficacy as key component to consider in parenting interventions, it offers a synthesis of the available evidence and insight for future research as well as recommendations.

The authors found inconsistent evidence on the effectiveness of programs to promote parental competence and skills in the context of children's healthy lifestyles. Future studies should ensure a sound theoretical framework on which the intervention is built and assessment methods are established. It is necessary to advance the knowledge on strategies to empower parents in their children's health promotion role. Parental competence and skills need to be scaled up in health promotion practice and research agenda. There is scope to enhance cross-disciplinary collaboration in the implementation of positive parenting programs. More evidence is needed on parental self-efficacy as a central element in the development of parental competences for the promotion of healthy childhood lifestyles.

LimitationsAlthough every effort was made to reduce potential bias in this review, some studies may have been overlooked as a result of the English and Spanish language search filter. Further, due to the differing and poor outcome measurement tools, the authors were unable to synthesize the data quantitatively through meta-analysis. However, the CASPe guide was used in order to minimize the possibility of bias.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The authors would like to thank Asociación de Amigos of the Universidad de Navarra for their support.

Please cite this article as: Ruiz-Zaldibar C, Serrano-Monzó I, Mujika A. Parental competence programs to promote positive parenting and healthy lifestyles in children: a systematic review. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2018;94:238–50.