To compare different neonatal outcomes according to the different types of treatments used in the management of gestational diabetes mellitus.

MethodsThis was a retrospective cohort study. The study population comprised pregnant women with gestational diabetes treated at a public maternity hospital from July 2010 to August 2014. The study included women aged at least 18 years, with a singleton pregnancy, who met the criteria for gestational diabetes mellitus. Blood glucose levels, fetal abdominal circumference, body mass index and gestational age were considered for treatment decision-making. The evaluated neonatal outcomes were: type of delivery, prematurity, weight in relation to gestational age, Apgar at 1 and 5min, and need for intensive care unit admission.

ResultsThe sample consisted of 705 pregnant women. The neonatal outcomes were analyzed based on the treatment received. Women treated with metformin were less likely to have children who were small for gestational age (95% CI: 0.09–0.66) and more likely to have a newborn adequate for gestational age (95% CI: 1.12–3.94). Those women treated with insulin had a lower chance of having a preterm child (95% CI: 0.02–0.78). The combined treatment with insulin and metformin resulted in higher chance for a neonate to be born large for gestational age (95% CI: 1.14–11.15) and lower chance to be born preterm (95% CI: 0.01–0.71). The type of treatment did not affect the mode of delivery, Apgar score, and intensive care unit admission.

ConclusionsThe pediatrician in the delivery room can expect different outcomes for diabetic mothers based on the treatment received.

Comparar diferentes desfechos neonatais de acordo com as diferentes modalidades de tratamentos do diabetes mellitus gestacional.

MétodosTrata-se de uma coorte retrospectiva. A população do estudo foi composta por gestantes com diabetes gestacional atendidas em uma maternidade pública desde Julho de 2010 a Agosto de 2014. Foram incluídas mulheres com idade mínima de 18 anos, gestação única e com critérios para diabetes mellitus gestacional. Para decisão terapêutica foram considerados glicemias, circunferência abdominal fetal, índice de massa corporal e idade gestacional. Os desfechos neonatais avaliados foram: via de parto, prematuridade, relação do peso com idade gestacional, Apgar no 1° e 5° minuto e necessidade de internação em unidade de terapia intensiva.

ResultadosA amostra foi composta por 705 gestantes. Os desfechos neonatais foram analisados com base na terapêutica recebida. Mulheres tratadas com metformina tiveram menor chance de terem filhos pequenos para a idade gestacional (IC 95%: 0,09-0,66) e maior chance de terem um filho adequado para a idade gestacional (IC 95%: 1,12-3,94). A gestante tratada com insulina teve menor chance de ter um filho prematuro (IC 95%: 0,02-0,78). O tratamento feito com a associação de insulina e metformina resultou em maior chance de um recém-nascido grande para a idade gestacional (IC 95%: 1,14-11,15) e menor chance de prematuridade (IC 95%: 0,01-0,71). A modalidade de tratamento não interferiu na via de parto, Apgar e internação em terapia intensiva.

ConclusõesO pediatra na sala de parto pode esperar diferentes desfechos para o filho de mãe diabética, com base no tratamento recebido.

According to a Latin American multicentric study, gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is the most prevalent metabolic disorder during pregnancy.1 It occurs in women whose pancreatic function is insufficient to overcome the insulin resistance due to the secretion of diabetogenic hormones by the placenta.2 In Brazil, the estimated prevalence of GDM varies from 2.4% to 7.2%.3

Both the mother and baby are affected by GDM, as both have a risk of developing undesirable outcomes.4 GDM affects the newborn as it increases the chance of macrosomia, fetal distress, metabolic disorders, hyperbilirubinemia, growth imbalance, and other complications.5 In order to minimize the consequences, it is necessary that the disease is diagnosed and treated early, because the outcomes are also related to the onset and duration of glucose intolerance, as well as the severity of GDM.5

Insulin has been used as the standard treatment for GDM for a long time. However, researchers have demonstrated the safety of oral hypoglycemic agents, such as metformin, in the initial treatment when diet alone is not enough to achieve the desired glucose levels.6,7

Studies that compared the use of metformin and insulin in the management of GDM demonstrated benefits with the use of oral hypoglycemic agents, such as fewer premature births and cesarean deliveries, reduction in maternal weight gain, and fewer adverse neonatal outcomes, such as macrosomia,6,8 hypoglycemia, jaundice, and admission to special neonatal care services.9

Thus, the study aimed to compare different neonatal outcomes according to the different treatment modalities used in the management of GDM.

MethodsThis was a retrospective cohort study based on the analysis of medical records, carried out from July 2010 to August 2014. The study sample was chosen by convenience; the population comprised pregnant women with GDM treated at a high-risk pregnancy outpatient clinic of a public maternity hospital. The project was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Hospital Regional Hans Dieter Schmidt, Joinville, SC, Brazil.

The study included all women aged ≥18 years with a singleton pregnancy and who met the criteria for GDM.10 The diagnosis of GDM was made based on the oral glucose tolerance test. The presence of at least one of the three following criteria confirmed the diagnosis: fasting glucose ≥92mg/dL, blood glucose within the first hour ≥180mg/dL, and glucose levels in the second hour ≥153mg/dL.11 Women whose babies had no malformations, who were followed-up at the outpatient clinic, and whose delivered occurred at the hospital were included.

Cases of intrauterine death (n=3) were excluded. Of these, two were part of the group treated with a combination of metformin and insulin and one had been treated with diet alone.

The first follow-up consultation of diabetic patients usually involves obstetrical ultrasound and routine screening for GDM. Furthermore, the pregnant women also attended a welcome lecture with a nutritionist and a physical therapist, in order to receive information regarding lifestyle changes (diet and physical exercise). Then, blood glucose was measured twice on consultation day (fasting and 1h after breakfast) and once per month at four different times (fasting and 1h after the start of each meal). The interval between consultations was of 15–21 days.

The blood glucose measurements (fasting and postprandial), fetal abdominal circumference, body mass index (BMI), and gestational age were considered for the therapeutic decision-making. Diet therapy was recommended to all pregnant women. In mild cases of GDM, the choice of therapy was metformin. When no glycemic control was achieved with a maximum dose of metformin (2.5g), it was associated with insulin therapy; insulin therapy was promptly started in more severe cases, without an attempt to use metformin. GDM cases were considered severe when fetal abdominal circumference was >90th percentile and maternal fasting glucose was >100mg/dL and postprandial (1h)>140mg/dL.

The collected data related to the women were full name, date of last menstrual period, probable date of delivery, gestational age, number of vaginal deliveries, cesarean sections and miscarriages, pre-pregnancy weight and height, results of oral glucose tolerance test, treatment used, and blood glucose level.

After birth, the medical records of the children born to diabetic mothers were analyzed in order to collect information about type of delivery, gestational age at birth, birth length and weight, Apgar score at the first and fifth minutes, morphology, and admission to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU).

The collected data were stored in a Microsoft Excel 2013 (Microsoft®, USA) spreadsheet. All the information obtained was analyzed using SPSS (IBM Corp. Released 2012. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0. USA). Means and standard deviations were calculated for the quantitative variables, whereas absolute and relative frequencies were used for qualitative variables. Binomial logistic regression models were constructed to assess the influence of different therapies on neonatal outcomes and adjust the effect of confounding variables. 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were established and p values <0.05 were considered significant.

ResultsThe study sample consisted of 705 pregnant women diagnosed with GDM and their respective babies. After the medical records were analyzed, the participants were grouped into four treatment groups: (1) diet, (2) metformin, (3) insulin, and (4) metformin+insulin.

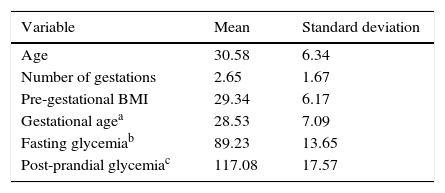

Table 1 shows the general characteristics of the study participants. Briefly, the patients had a mean age of 30.6 years (SD±6.34) and mean number of pregnancies of 2.65 (SD±1.67). Cesarean section was the type of delivery in 52.1% of the cases. Regarding GDM treatment, most pregnant women were prescribed diet therapy as the treatment of choice (41.6%); 35.5% of the women were treated with metformin, 15% with insulin, and the remainder with a metformin and insulin association (7.9%).

Hypertensive disease of pregnancy was present in 72 patients. Twenty-six mothers were treated with metformin, 16 with diet therapy, 15 with insulin alone, and 15 with the association of insulin and metformin. Those who received the combination of metformin and insulin had a higher chance of having hypertensive disease of pregnancy (AOR 2.38 [1.07–5.28]) when compared with those under the diet treatment. The other GDM treatments showed no difference in relation to this maternal outcome.

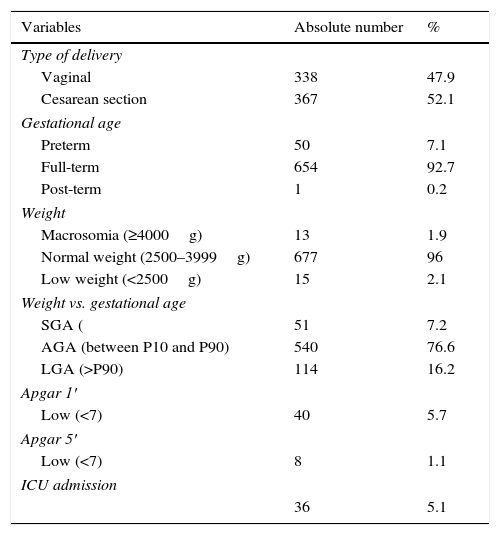

Regarding the characteristics of the newborns (Table 2), the mean GA at delivery was 38.6 weeks (SD±1.38). Thirty-four babies were preterm (4.8%); 40 (5.6%) had low Apgar score at the first minute and eight (1.1%) had low Apgar score at the fifth minute. A total of 114 (16.1%) newborns were large for gestational age and 51 (7.2%) were born small for gestational age. Thirty-six (5.1%) newborns needed NICU admission.

General characteristics of the newborns (n=705).

| Variables | Absolute number | % |

|---|---|---|

| Type of delivery | ||

| Vaginal | 338 | 47.9 |

| Cesarean section | 367 | 52.1 |

| Gestational age | ||

| Preterm | 50 | 7.1 |

| Full-term | 654 | 92.7 |

| Post-term | 1 | 0.2 |

| Weight | ||

| Macrosomia (≥4000g) | 13 | 1.9 |

| Normal weight (2500–3999g) | 677 | 96 |

| Low weight (<2500g) | 15 | 2.1 |

| Weight vs. gestational age | ||

| SGA ( | 51 | 7.2 |

| AGA (between P10 and P90) | 540 | 76.6 |

| LGA (>P90) | 114 | 16.2 |

| Apgar 1′ | ||

| Low (<7) | 40 | 5.7 |

| Apgar 5′ | ||

| Low (<7) | 8 | 1.1 |

| ICU admission | ||

| 36 | 5.1 | |

SGA, small for gestational age; AGA, adequate for gestational age; LGA, large for gestational age; ICU, intensive care unit.

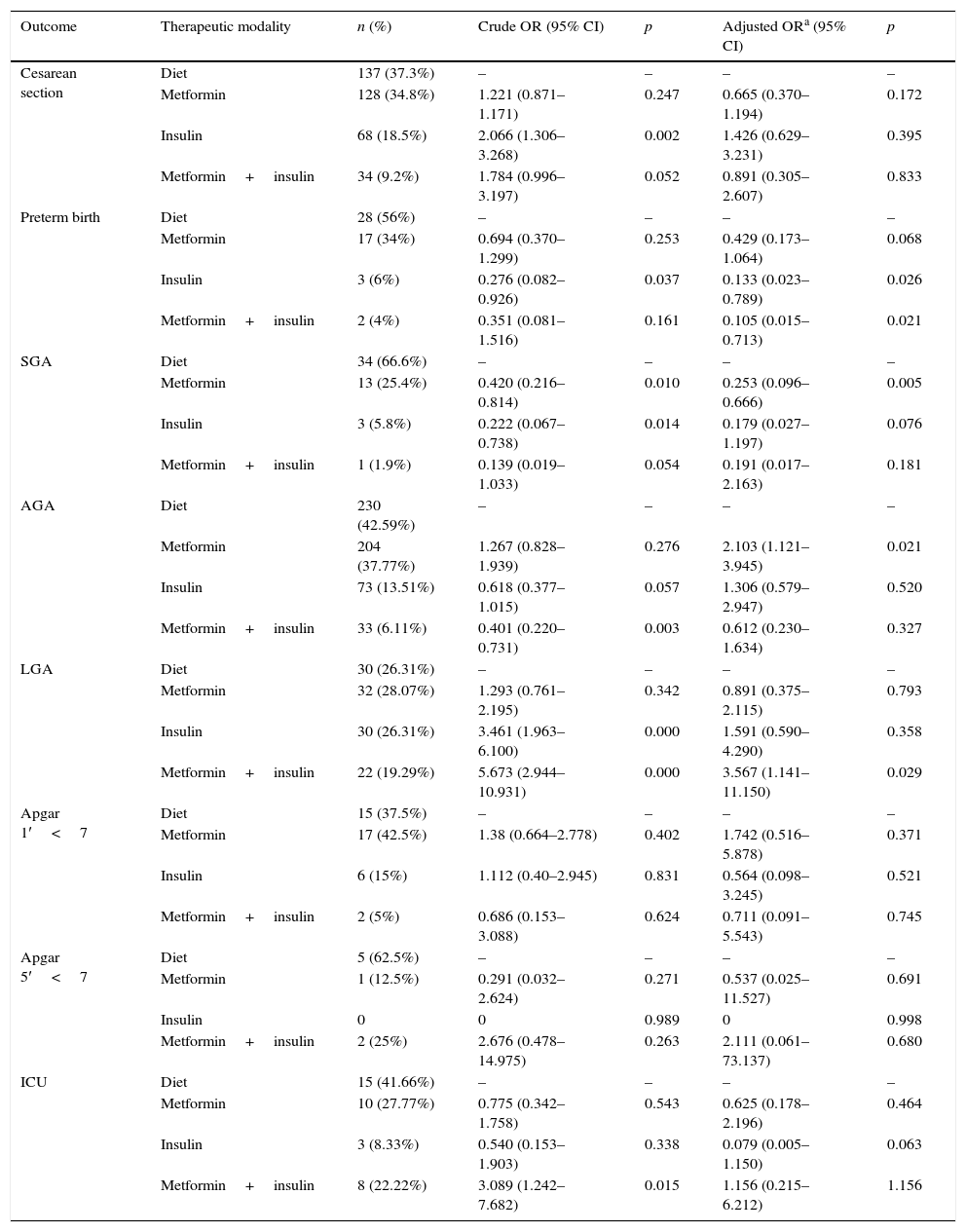

The neonatal outcomes were analyzed based on the GDM therapy used (Table 3), taking into account that the treatments were compared with the diet therapy.

Multivariate analysis of neonatal outcomes according to type of gestational diabetes mellitus therapy (n=705).

| Outcome | Therapeutic modality | n (%) | Crude OR (95% CI) | p | Adjusted ORa (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cesarean section | Diet | 137 (37.3%) | – | – | – | – |

| Metformin | 128 (34.8%) | 1.221 (0.871–1.171) | 0.247 | 0.665 (0.370–1.194) | 0.172 | |

| Insulin | 68 (18.5%) | 2.066 (1.306–3.268) | 0.002 | 1.426 (0.629–3.231) | 0.395 | |

| Metformin+insulin | 34 (9.2%) | 1.784 (0.996–3.197) | 0.052 | 0.891 (0.305–2.607) | 0.833 | |

| Preterm birth | Diet | 28 (56%) | – | – | – | – |

| Metformin | 17 (34%) | 0.694 (0.370–1.299) | 0.253 | 0.429 (0.173–1.064) | 0.068 | |

| Insulin | 3 (6%) | 0.276 (0.082–0.926) | 0.037 | 0.133 (0.023–0.789) | 0.026 | |

| Metformin+insulin | 2 (4%) | 0.351 (0.081–1.516) | 0.161 | 0.105 (0.015–0.713) | 0.021 | |

| SGA | Diet | 34 (66.6%) | – | – | – | – |

| Metformin | 13 (25.4%) | 0.420 (0.216–0.814) | 0.010 | 0.253 (0.096–0.666) | 0.005 | |

| Insulin | 3 (5.8%) | 0.222 (0.067–0.738) | 0.014 | 0.179 (0.027–1.197) | 0.076 | |

| Metformin+insulin | 1 (1.9%) | 0.139 (0.019–1.033) | 0.054 | 0.191 (0.017–2.163) | 0.181 | |

| AGA | Diet | 230 (42.59%) | – | – | – | – |

| Metformin | 204 (37.77%) | 1.267 (0.828–1.939) | 0.276 | 2.103 (1.121–3.945) | 0.021 | |

| Insulin | 73 (13.51%) | 0.618 (0.377–1.015) | 0.057 | 1.306 (0.579–2.947) | 0.520 | |

| Metformin+insulin | 33 (6.11%) | 0.401 (0.220–0.731) | 0.003 | 0.612 (0.230–1.634) | 0.327 | |

| LGA | Diet | 30 (26.31%) | – | – | – | – |

| Metformin | 32 (28.07%) | 1.293 (0.761–2.195) | 0.342 | 0.891 (0.375–2.115) | 0.793 | |

| Insulin | 30 (26.31%) | 3.461 (1.963–6.100) | 0.000 | 1.591 (0.590–4.290) | 0.358 | |

| Metformin+insulin | 22 (19.29%) | 5.673 (2.944–10.931) | 0.000 | 3.567 (1.141–11.150) | 0.029 | |

| Apgar 1′<7 | Diet | 15 (37.5%) | – | – | – | – |

| Metformin | 17 (42.5%) | 1.38 (0.664–2.778) | 0.402 | 1.742 (0.516–5.878) | 0.371 | |

| Insulin | 6 (15%) | 1.112 (0.40–2.945) | 0.831 | 0.564 (0.098–3.245) | 0.521 | |

| Metformin+insulin | 2 (5%) | 0.686 (0.153–3.088) | 0.624 | 0.711 (0.091–5.543) | 0.745 | |

| Apgar 5′<7 | Diet | 5 (62.5%) | – | – | – | – |

| Metformin | 1 (12.5%) | 0.291 (0.032–2.624) | 0.271 | 0.537 (0.025–11.527) | 0.691 | |

| Insulin | 0 | 0 | 0.989 | 0 | 0.998 | |

| Metformin+insulin | 2 (25%) | 2.676 (0.478–14.975) | 0.263 | 2.111 (0.061–73.137) | 0.680 | |

| ICU | Diet | 15 (41.66%) | – | – | – | – |

| Metformin | 10 (27.77%) | 0.775 (0.342–1.758) | 0.543 | 0.625 (0.178–2.196) | 0.464 | |

| Insulin | 3 (8.33%) | 0.540 (0.153–1.903) | 0.338 | 0.079 (0.005–1.150) | 0.063 | |

| Metformin+insulin | 8 (22.22%) | 3.089 (1.242–7.682) | 0.015 | 1.156 (0.215–6.212) | 1.156 |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; SGA, small for gestational age; AGA, adequate for gestational age; LGA, large for gestational age; ICU, intensive care unit.

The type of treatment did not affect the outcome type of delivery, Apgar scores at the first and fifth minutes, and need for NICU admission.

Pregnant women who were treated with metformin had a lower chance of having a small for gestational age (SGA) child and also had slightly over twice the chance of having a baby with adequate weight for gestational age (AGA). Mothers who received insulin treatment had a lower chance that their children would be born preterm. Similarly, mothers treated with the combination of metformin and insulin were also less likely to have preterm children. In addition, women treated with this combination therapy had more than three times the chance of having a large for gestational age (LGA) child.

DiscussionThe present study evaluated different neonatal outcomes according to the treatment of choice for GDM. In the present population, 16.2% of newborns were classified as LGA. Treatment with the association of insulin and metformin was responsible for a 3.5-fold higher chance of an LGA child (AOR 3.56 [1.14–11.15]). The rate of SGA newborns was 7.2%, and the chance was lower in the group of women treated with metformin (AOR 0.25 [0.09–0.66]). The percentage of AGA newborns was 76.6%; the use of metformin was associated with a two-fold higher chance of AGA newborns (AOR 2.10 [1.12–3.94]).

The percentage of preterm infants was 7.1%. Those treated with insulin had a lower chance for this outcome (AOR 0.13 [0.023–0.78]), as well as those treated with a combination of insulin and metformin (AOR 0.10 [0.01–0.71]). NICU admission rate was 5.1%; the treatment modalities did not affect the need for it. The percentage of cesarean deliveries was 52.1%, and the GDM treatment modalities did not affect the type of delivery. There was no increased chance of low Apgar score, both at the first and the fifth minutes, according to the therapy used.

The present study is important, because although insulin is considered the standard classical treatment for the disease, metformin has demonstrated good results in GDM control and appears to attenuate the possible neonatal outcomes.6,7

The physicians responsible for pregnant women with GDM need to be aware of the maternal and neonatal risks related to this metabolic disorder.12 One of the most common complications of GDM is an LGA child.12 When the newborn is classified as LGA, in addition to the fact that the birth is associated with increased risk of obstetric traumas and shoulder dystocia, immediate effects such as hypoglycemia and respiratory dysfunction may also occur.12

In the present study, 16.2% of newborns were classified as LGA. In the literature, this percentage ranges from 13.4 to 30%.13–16 Patients who received the association of insulin and metformin had a 3.5-fold higher risk of having an LGA baby. There was no difference for the other treatments. The literature showed higher rates of LGA births in women treated with insulin when compared with those treated with metformin or diet therapy.6

Among the perinatal complications of an LGA newborn, are noteworthy the increased risk of meconium aspiration, clavicle fracture, perinatal hypoxia, hypoglycemia, hyperbilirubinemia, transient tachypnea, brachial plexus injury, shoulder dystocia, and even neonatal death.17 These babies were also at increased risk at the moment of treatment choice, which was more aggressive due to the fetal characteristics observed during prenatal care.

An intensive therapy for GDM may result in a decrease of fetal weight, preventing LGA newborns. However, one consequence is the increase in the number of SGA newborns.18 Such disorders are also related to early neonatal complications and diseases in adulthood.18,19

In this study, the incidence of SGA infants was 7.2%, while in the literature it ranged from 3% to 10.5%.19,20 The chance of having an SGA newborn was lower in the group of women treated with metformin. The study by Goh et al. showed no difference for the SGA outcome according to the different treatments.6

Being SGA is as unfavorable as being LGA, since both are associated with higher morbidity and mortality in the short- and long-term. Therefore, preventing the occurrence of SGA is as important as preventing that of LGA.20 In a select group of pregnant women, when there is indirect evidence of fetal hyperinsulinization at the ultrasound, the drug dose could be reduced.

For that purpose, it might be necessary to consider the fetal weight estimated by the ultrasound in the therapeutic option of patients treated with metformin, as there was a higher risk of SGA. Thus, an approach based on ultrasound parameters can provide a more flexible therapeutic model for those patients whose newborn weight estimated by the ultrasound is reduced and therefore, the dose can be decreased.20

The quality of the treatment provided to diabetic pregnant women has a direct effect on the newborn weight classification. Considering that AGA is the treatment goal, treatment success can be assessed by this parameter. In the present study, the incidence of AGA infants was 76.6%. The literature reports that AGA rates are around 86.6%.20 Metformin was shown to be very satisfactory in this regard, as its use was associated with a two-fold higher chance of AGA newborns.

Spontaneous and medically indicated preterm birth occurs more often in diabetic pregnant women than in their non-diabetic peers.5 Preterm newborns have a higher rate of infant mortality and morbidity when compared with children born at term. Short-term complications of prematurity are related to the cardiovascular and respiratory systems21; disorders such as cerebral palsy may occur as a long-term neurodevelopmental complication.22 Preterm newborns are more likely to develop hypertension, obesity, and cardiovascular disease in adulthood.23

The percentage of preterm infants in this study was 7.1%. In other studies, the percentage of preterm infants ranged from 4% to 16%.5,6 The present study showed that preterm infants are more commonly born to mothers treated with insulin or the combination of metformin and insulin than to those under diet therapy. These data corroborate the results of a similar study.6 Furthermore, the comparison of the prematurity outcome between the diet and metformin therapies showed no significant difference,6 similarly to the present study.

Given the various complications to which the child of a mother with GDM is predisposed, sometimes a more intensive therapy is necessary. Reasons for NICU admission include congenital abnormalities (such as cardiovascular malformations), prematurity, perinatal asphyxia, respiratory distress, and metabolic complications (hypoglycemia, hypocalcemia, polycythemia, and hyperbilirubinemia), among others.5 In the present study, the NICU admission rate was 5.1%. This value corroborates other values found in the literature (2%–6%),1,20 but is dissimilar from others, in which the need for NICU admission ranged from 15%6 to 23.5%.5

In the present study, the type of treatment did not affect the need for NICU admission, while other authors found that infants born to women treated with insulin had higher rates of NICU admission when compared with pregnant women who received treatment with metformin or diet therapy.6

Since pregnant diabetic women have a higher risk of having LGA children, the indication for cesarean deliveries may increase. The purpose of this type of delivery is to prevent trauma during the birth of infants with estimated weight ≥4500g.17

The percentage of cesarean deliveries in the study was 52.1%. This is similar to the percentage of cesarean sections in other Brazilian studies,24,25 but rates are lower in the international scenario.6,26 This difference may be due to the dissemination of cesarean practice in Brazil, unlike other countries. GDM treatment modalities did not affect the type of delivery. In contrast, another study showed that the cesarean section was more prevalent in women treated with insulin.6

The Apgar score is used as an evaluation method of the newborn's birth quality between the first and fifth minutes of life.27 It assesses the immediate adjustment of the newborn to extrauterine life, analyzing the baby's vitality. It consists of the evaluation of five items of the newborn's physical examination: heart rate, respiratory effort, muscle tone, reflex irritability, and skin color.27

The Apgar score at the first minute is considered a diagnosis of the present situation, an index that can represent a sign of asphyxiation and the need for mechanical ventilation.27 As for the Apgar score at the fifth minute, it is considered to be more accurate, leading to the prognosis of neurological health and outcomes such as neurological sequelae or death.27

In the present population, similarly to other studies,5,26 there was no increased risk of low Apgar, either at the first or the fifth minute, according to the therapy used. This may demonstrate the success in the care provided to newborns of diabetic mothers.28

The outcomes of cesarean delivery and Apgar scores at the first and fifth minutes and need for NICU admission were not different between the treatments.

Due to the methodology used in the study, there were some limitations to the comparison of results, since few studies used the same method. Another point to be highlighted is the heterogeneity of participants in each therapeutic modality group, because each treatment was aimed at a distinct profile of pregnant women.

It can be concluded that the pediatrician in the delivery room can expect different outcomes for children born to diabetic mothers based on the treatment that she received during pregnancy. Women treated with metformin are less likely to have SGA children and more likely to have an AGA child. A pregnant woman who was treated with insulin has a lower chance of having a preterm child. If the GDM treatment of was a combination of insulin and metformin, there is a higher chance of the child being born LGA and a lower chance of being preterm.

For the other assessed outcomes (type of delivery, Apgar score, and need for NICU admission), there were no differences between treatment modalities.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

To Darcy Vargas Maternity Hospital.

Please cite this article as: Silva AL, Amaral AR, Oliveira DS, Martins L, Silva MR, Silva JC. Neonatal outcomes according to different therapies for gestational diabetes mellitus. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2017;93:87–93.

Study carried out at Maternidade Darcy Vargas, Joinville, SC, Brazil.