this systematic review aims to explore and describe the studies that have as a primary outcome the identification of mothers’ perception of the nutritional status of their children.

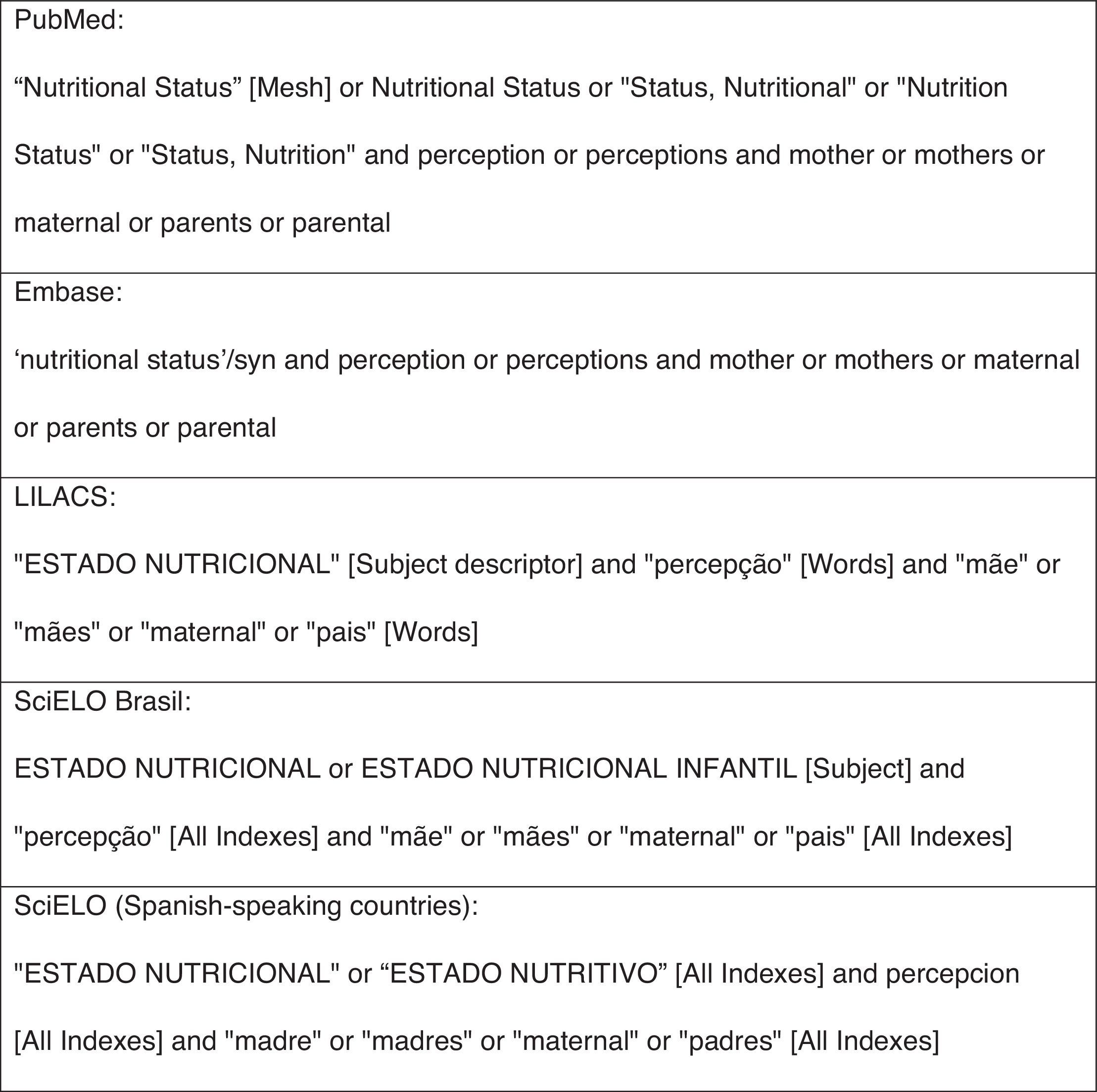

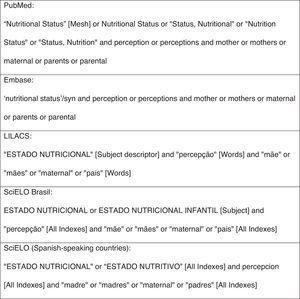

Sourcesthe PubMed, Embase, LILACS, and SciELO databases were researched, regardless of language or publication date. The terms used for the search, with its variants, were: Nutritional Status, Perception, Mother, Maternal, Parents, Parental.

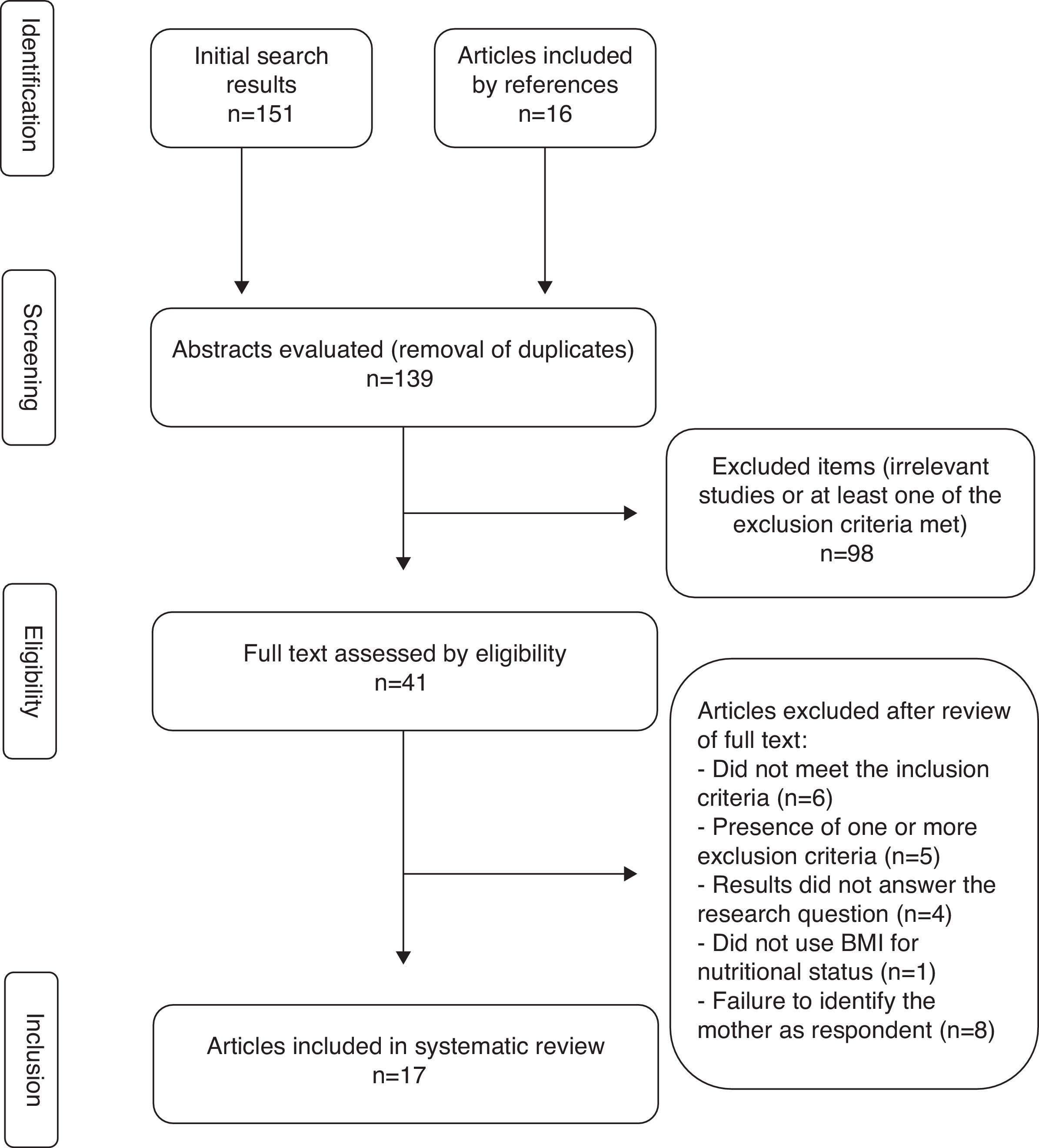

Summary of the findingsafter screening of 167 articles, 41 were selected for full text reading, of which 17 were included in the review and involved the evaluation of the perception of mothers on the nutritional status of 57,700 children and adolescents. The methodological quality of the studies ranged from low to excellent. The proportion of mothers who inadequately perceived the nutritional status of their children was high, and was the most common underestimation for children with overweight or obesity.

Conclusiondespite the increasing prevalence of obesity in pediatric age, mothers have difficulty in properly perceiving the nutritional status of their children, which may compromise referral to treatment programs.

esta revisão sistemática tem por objetivo explorar e descrever os estudos que apresentam como desfecho primário a identificação da percepção das mães quanto ao estado nutricional de seus filhos.

Fonte dos dadosforam utilizadas as bases de dados PubMed, Embase, LILACS e SciELO, sem distinção de idioma ou data de publicação. Os termos utilizados para a busca, com suas variações, foram: Nutritional Status, Perception, Mother, Maternal, Parents, Parental.

Síntese dos dadosapós triagem dos 167 artigos encontrados, restaram 41 artigos para leitura do texto completo, sendo incluídos 17 artigos, que envolveram a avaliação da percepção de mães sobre o estado nutricional de 57.700 crianças e adolescentes. A qualidade metodológica dos artigos variou de baixa a excelente. A proporção de mães que percebiam inadequadamente o estado nutricional dos filhos foi elevada, sendo mais comum a subestimativa para crianças com sobrepeso ou obesidade.

Conclusãoapesar do aumento da prevalência de obesidade em faixas pediátricas, as mães têm dificuldade de perceber adequadamente o estado nutricional de seus filhos, o que pode comprometer o encaminhamento para programas de tratamento.

Obesity is one of the most common non-communicable chronic diseases in childhood, with a tendency to extend into adulthood,1,2 resulting in the early onset of other associated chronic diseases, such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, and type 2 diabetes, among other cardiometabolic risk factors.3–5

A study conducted in Porto Alegre, state of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, demonstrated that obese adolescents from municipal schools had metabolic syndrome prevalence of 51.2% and insulin resistance of 80.1%, very close to the results of other studies performed in Brazil and in other countries.6

The prevalence of excess weight has increased in all age groups in Brazil, similar to what has occurred worldwide. Data from the Family Budget Survey7 has demonstrated that the proportion of obese children has quadrupled in the last 20 years, whereas it has tripled in adolescents during the same period. These findings do not differ significantly from trends observed in developed countries.8,9

Considering that the treatment programs for obesity in childhood and adolescence have not shown significant results,2,10,11 the key point on the fight against this disease should be prevention, based on an active lifestyle and healthy eating habits.12

Several studies have demonstrated that obesity is a multifactorial disease, showing a strong association with family dynamics; thus, the success of prevention and treatment programs depends on the involvement of the family as a whole.13–15 Hence, the first step is the acknowledgement by the parents of the nutritional status of their children, identifying excess weight as a health risk.16,17

Not many studies have assessed the mothers’ perception of the nutritional status of their children, and most of them have demonstrated that there is a tendency for the mothers to underestimate the nutritional status of their children, not recognizing their obese children as such.

This fact deserves much attention, since if the parents, particularly the mother, do not recognize their obese children as such, they will not be concerned about referring them for treatment, nor will encourage them to change their lifestyle.18

In this sense, this systematic review aimed to investigate and describe the studies that have as primary outcome the identification of mothers’ perception regarding the nutritional status of their children.

MethodsFor the literature review of the perception of mothers about the nutritional status of their children the PubMed, Embase, LILACS, and SciELO databases were researched, regardless of language or publication date. The terms used for the search and their variants were: Nutritional Status, Perception, Mother, Maternal, Parents, and Parental, as described in Fig. 1. The terms were adapted to the search engines in each database used.

The inclusion criteria for this review were: articles that investigated the perception of mothers on the nutritional status of their children; studies of children aged between 2 and 19 years where the outcome was the assessment of the difference between the actual nutritional status (classified by body mass index [BMI]) and nutritional status perceived by the mother.

The estimate of nutritional status by BMI can be performed with different cutoff points obtained in different studies; the criteria most often reported in the literature are those proposed by the International Obesity Task Force (IOTF),19 by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC),20,21 and by the World Health Organization (WHO).22

The percentile curves used by IOTF for children and adolescents aged 2 to 17 years define overweight as ≥ the 85th percentile and obesity ≥ the 95th percentile, identifying these points as similar to the cutoffs used for adults, which are 25kg/m2 for overweight and 30kg/m2 for obesity. The cutoffs used by the WHO for children and adolescents aged 2 to 19 years define overweight as ≥ the 85th percentile and obesity as ≥ the 97th percentile. The CDC classification for children and adolescents aged from 2 to 19 years establishes overweight as ≥ the 85th percentile and obesity as ≥ the 95th percentile.

Some studies used specific cutoffs for the study population, which differ from the aforementioned criteria.23,24

For studies that assessed the perception of both parents, only the results related to the mother's perception were extracted.

Exclusion criteria were the presence, in the study samples, of diseases that affect nutritional status, such as eating disorders and genetic syndromes, as well as studies that were aimed at the perception of nutritional status in children with different types of cancer.

The search was performed by two reviewers, separately, who selected studies first by reading the titles, then by reading the abstracts, and then proceeded to read the full article. In addition to the articles selected from the databases, a review of the references of each selected article was performed, in order to find studies that were not retrieved in the main article databases. Article eligibility was independently assessed by two reviewers, and discrepancies were resolved jointly by all authors.

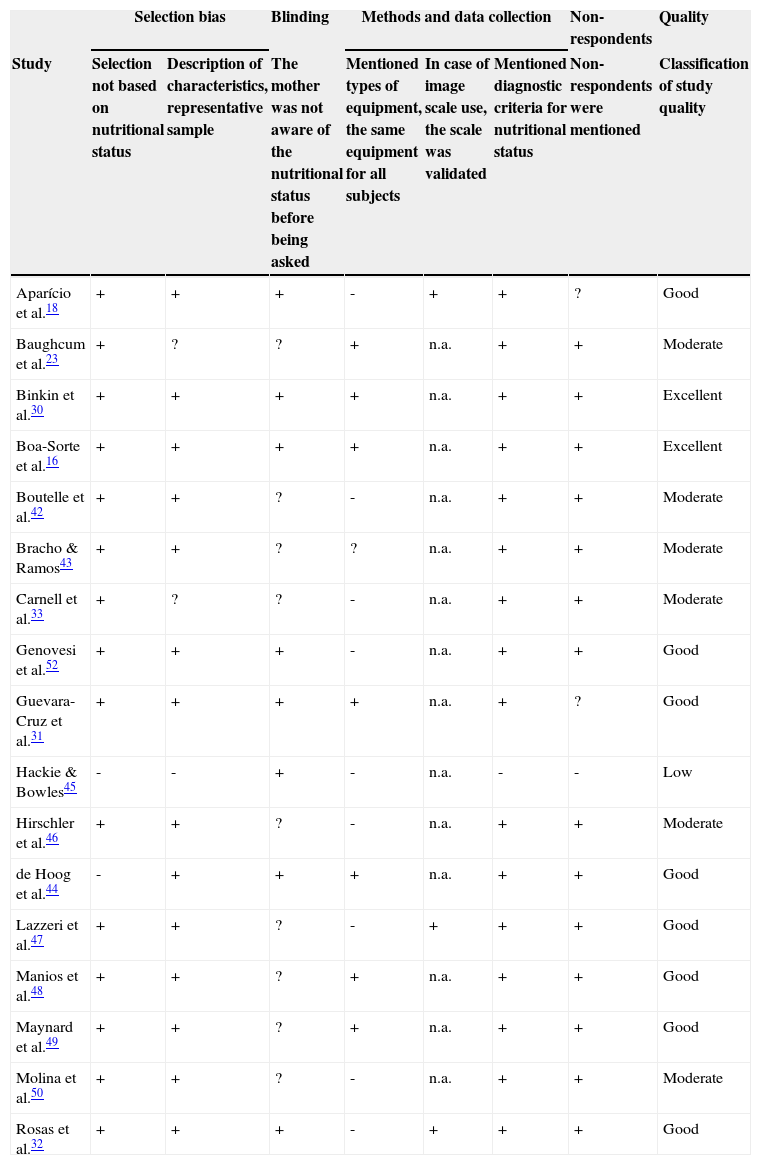

Considering that there is no article quality assessment tool for descriptive and cross-sectional studies, and in order to meet the purpose of this study, a tool adapted by Rietmeijer-Mentink et al.25 was used in this review, which is based on the Cochrane criterion for the assessment of diagnostic studies (Table 1). Thus, the methodological quality of the articles that included a verbal description of the maternal perception regarding the nutritional status of their children was based on six items; the articles were categorized as low (zero to two positive items), moderate (three to four positive items), good (five positive items), and excellent quality (six positive items). The quality of the articles that used body image scales was based on seven items; the categorization was similar, except for the good (five to six positive items) and excellent quality (seven positive items) range.

Results of the evaluation of the quality of the articles included in the review.

| Selection bias | Blinding | Methods and data collection | Non- respondents | Quality | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Selection not based on nutritional status | Description of characteristics, representative sample | The mother was not aware of the nutritional status before being asked | Mentioned types of equipment, the same equipment for all subjects | In case of image scale use, the scale was validated | Mentioned diagnostic criteria for nutritional status | Non-respondents were mentioned | Classification of study quality |

| Aparício et al.18 | + | + | + | - | + | + | ? | Good |

| Baughcum et al.23 | + | ? | ? | + | n.a. | + | + | Moderate |

| Binkin et al.30 | + | + | + | + | n.a. | + | + | Excellent |

| Boa-Sorte et al.16 | + | + | + | + | n.a. | + | + | Excellent |

| Boutelle et al.42 | + | + | ? | - | n.a. | + | + | Moderate |

| Bracho & Ramos43 | + | + | ? | ? | n.a. | + | + | Moderate |

| Carnell et al.33 | + | ? | ? | - | n.a. | + | + | Moderate |

| Genovesi et al.52 | + | + | + | - | n.a. | + | + | Good |

| Guevara-Cruz et al.31 | + | + | + | + | n.a. | + | ? | Good |

| Hackie & Bowles45 | - | - | + | - | n.a. | - | - | Low |

| Hirschler et al.46 | + | + | ? | - | n.a. | + | + | Moderate |

| de Hoog et al.44 | - | + | + | + | n.a. | + | + | Good |

| Lazzeri et al.47 | + | + | ? | - | + | + | + | Good |

| Manios et al.48 | + | + | ? | + | n.a. | + | + | Good |

| Maynard et al.49 | + | + | ? | + | n.a. | + | + | Good |

| Molina et al.50 | + | + | ? | - | n.a. | + | + | Moderate |

| Rosas et al.32 | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | Good |

n.a., not applicable.

A search of the electronic databases resulted in 151 articles, from which 28 duplicates were discarded. Screening for titles and abstracts of the remaining 123 articles resulted in 31 articles to be read as full text. Moreover, after reading the references of these articles, 16 extra article abstracts were read, from which ten were selected to be read as full text. After applying the exclusion criteria, a total of 17 articles remained in this systematic review (Fig. 2).

The assessment of methodological quality of the articles demonstrated that only one had low quality and two had excellent quality; six were classified as moderate quality and eight as good quality (Table 1).

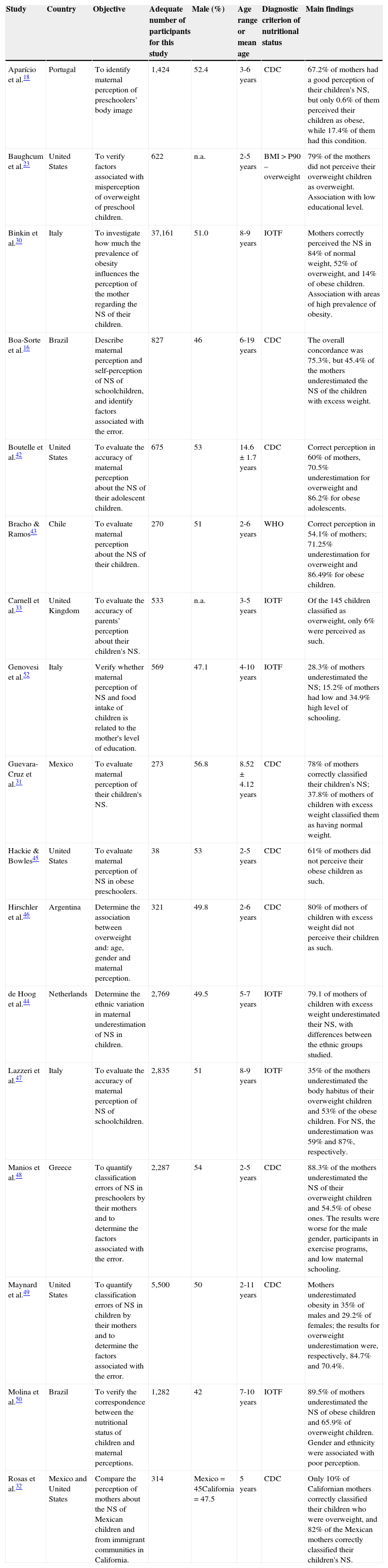

The description of the articles, including the country of origin, objective, sample characteristics, diagnostic criterion used for the nutritional status, and main results are shown in Table 2.

Characteristics of studies included in the review.

| Study | Country | Objective | Adequate number of participants for this study | Male (%) | Age range or mean age | Diagnostic criterion of nutritional status | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aparício et al.18 | Portugal | To identify maternal perception of preschoolers’ body image | 1,424 | 52.4 | 3-6 years | CDC | 67.2% of mothers had a good perception of their children's NS, but only 0.6% of them perceived their children as obese, while 17.4% of them had this condition. |

| Baughcum et al.23 | United States | To verify factors associated with misperception of overweight of preschool children. | 622 | n.a. | 2-5 years | BMI > P90 – overweight | 79% of the mothers did not perceive their overweight children as overweight. Association with low educational level. |

| Binkin et al.30 | Italy | To investigate how much the prevalence of obesity influences the perception of the mother regarding the NS of their children. | 37,161 | 51.0 | 8-9 years | IOTF | Mothers correctly perceived the NS in 84% of normal weight, 52% of overweight, and 14% of obese children. Association with areas of high prevalence of obesity. |

| Boa-Sorte et al.16 | Brazil | Describe maternal perception and self-perception of NS of schoolchildren, and identify factors associated with the error. | 827 | 46 | 6-19 years | CDC | The overall concordance was 75.3%, but 45.4% of the mothers underestimated the NS of the children with excess weight. |

| Boutelle et al.42 | United States | To evaluate the accuracy of maternal perception about the NS of their adolescent children. | 675 | 53 | 14.6 ± 1.7 years | CDC | Correct perception in 60% of mothers, 70.5% underestimation for overweight and 86.2% for obese adolescents. |

| Bracho & Ramos43 | Chile | To evaluate maternal perception about the NS of their children. | 270 | 51 | 2-6 years | WHO | Correct perception in 54.1% of mothers; 71.25% underestimation for overweight and 86.49% for obese children. |

| Carnell et al.33 | United Kingdom | To evaluate the accuracy of parents’ perception about their children's NS. | 533 | n.a. | 3-5 years | IOTF | Of the 145 children classified as overweight, only 6% were perceived as such. |

| Genovesi et al.52 | Italy | Verify whether maternal perception of NS and food intake of children is related to the mother's level of education. | 569 | 47.1 | 4-10 years | IOTF | 28.3% of mothers underestimated the NS; 15.2% of mothers had low and 34.9% high level of schooling. |

| Guevara-Cruz et al.31 | Mexico | To evaluate maternal perception of their children's NS. | 273 | 56.8 | 8.52 ± 4.12 years | CDC | 78% of mothers correctly classified their children's NS; 37.8% of mothers of children with excess weight classified them as having normal weight. |

| Hackie & Bowles45 | United States | To evaluate maternal perception of NS in obese preschoolers. | 38 | 53 | 2-5 years | CDC | 61% of mothers did not perceive their obese children as such. |

| Hirschler et al.46 | Argentina | Determine the association between overweight and: age, gender and maternal perception. | 321 | 49.8 | 2-6 years | CDC | 80% of mothers of children with excess weight did not perceive their children as such. |

| de Hoog et al.44 | Netherlands | Determine the ethnic variation in maternal underestimation of NS in children. | 2,769 | 49.5 | 5-7 years | IOTF | 79.1 of mothers of children with excess weight underestimated their NS, with differences between the ethnic groups studied. |

| Lazzeri et al.47 | Italy | To evaluate the accuracy of maternal perception of NS of schoolchildren. | 2,835 | 51 | 8-9 years | IOTF | 35% of the mothers underestimated the body habitus of their overweight children and 53% of the obese children. For NS, the underestimation was 59% and 87%, respectively. |

| Manios et al.48 | Greece | To quantify classification errors of NS in preschoolers by their mothers and to determine the factors associated with the error. | 2,287 | 54 | 2-5 years | CDC | 88.3% of the mothers underestimated the NS of their overweight children and 54.5% of obese ones. The results were worse for the male gender, participants in exercise programs, and low maternal schooling. |

| Maynard et al.49 | United States | To quantify classification errors of NS in children by their mothers and to determine the factors associated with the error. | 5,500 | 50 | 2-11 years | CDC | Mothers underestimated obesity in 35% of males and 29.2% of females; the results for overweight underestimation were, respectively, 84.7% and 70.4%. |

| Molina et al.50 | Brazil | To verify the correspondence between the nutritional status of children and maternal perceptions. | 1,282 | 42 | 7-10 years | IOTF | 89.5% of mothers underestimated the NS of obese children and 65.9% of overweight children. Gender and ethnicity were associated with poor perception. |

| Rosas et al.32 | Mexico and United States | Compare the perception of mothers about the NS of Mexican children and from immigrant communities in California. | 314 | Mexico = 45California = 47.5 | 5 years | CDC | Only 10% of Californian mothers correctly classified their children who were overweight, and 82% of the Mexican mothers correctly classified their children's NS. |

NS, nutritional status; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; IOTF, the International Obesity Task Force; WHO, World Health Organization

The studies were published between 2000 and 2013. The age of the children ranged from 2 to 19 years, and studies with children aged 2 to 6 years predominated. In total, 57,700 mother-child pairs were part of this review, of which 18,656 children were overweight or obese (32.3%). Obesity was detected in 6,666 children (11.6%). According to the mothers’ perception, only 5,501 children were overweight or obese (9.53%).

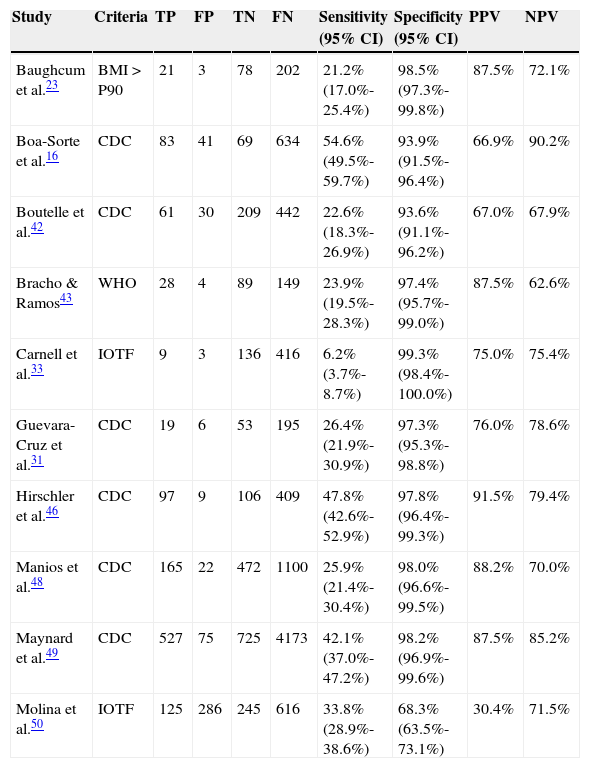

In ten of the 17 articles included in the review, extracted data allowed for the calculations of sensitivity and specificity of mothers’ perception about the nutritional status of their children (Table 3). The sensitivity ranged from 6.2% to 54.6%, indicating low capacity of mothers to perceive overweight in their children. Specificity was higher than 90.0% for nine of the ten studies, indicating good capacity of mothers to recognize the nutritional status of their children when they had normal weight.

Sensitivity and specificity values of maternal perception, calculated based on data provided by the studies.

| Study | Criteria | TP | FP | TN | FN | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | PPV | NPV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baughcum et al.23 | BMI > P90 | 21 | 3 | 78 | 202 | 21.2% (17.0%-25.4%) | 98.5% (97.3%-99.8%) | 87.5% | 72.1% |

| Boa-Sorte et al.16 | CDC | 83 | 41 | 69 | 634 | 54.6% (49.5%-59.7%) | 93.9% (91.5%-96.4%) | 66.9% | 90.2% |

| Boutelle et al.42 | CDC | 61 | 30 | 209 | 442 | 22.6% (18.3%-26.9%) | 93.6% (91.1%-96.2%) | 67.0% | 67.9% |

| Bracho & Ramos43 | WHO | 28 | 4 | 89 | 149 | 23.9% (19.5%-28.3%) | 97.4% (95.7%-99.0%) | 87.5% | 62.6% |

| Carnell et al.33 | IOTF | 9 | 3 | 136 | 416 | 6.2% (3.7%-8.7%) | 99.3% (98.4%-100.0%) | 75.0% | 75.4% |

| Guevara-Cruz et al.31 | CDC | 19 | 6 | 53 | 195 | 26.4% (21.9%-30.9%) | 97.3% (95.3%-98.8%) | 76.0% | 78.6% |

| Hirschler et al.46 | CDC | 97 | 9 | 106 | 409 | 47.8% (42.6%-52.9%) | 97.8% (96.4%-99.3%) | 91.5% | 79.4% |

| Manios et al.48 | CDC | 165 | 22 | 472 | 1100 | 25.9% (21.4%-30.4%) | 98.0% (96.6%-99.5%) | 88.2% | 70.0% |

| Maynard et al.49 | CDC | 527 | 75 | 725 | 4173 | 42.1% (37.0%-47.2%) | 98.2% (96.9%-99.6%) | 87.5% | 85.2% |

| Molina et al.50 | IOTF | 125 | 286 | 245 | 616 | 33.8% (28.9%-38.6%) | 68.3% (63.5%-73.1%) | 30.4% | 71.5% |

CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; IOTF, the International Obesity Task Force; WHO, World Health Organization; TP, true positive; FP, false positive; FN, false negative; TN, true negative; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value.

This systematic review aimed to explore and describe the studies that had as primary outcome the identification of mothers’ perception about the nutritional status of their children. A total of 57,700 mother-child pairs were part of this review and overweight or obesity was present in 18,656 children (32.3%). As for obesity, it was detected in 6,666 children (11.6%). However, according to the perception of mothers, only 5,501 children were overweight or obese (9.53%).

Other review studies investigated the perception of the mother or of the parents about the nutritional status of their children,26–29 but the approaches were different from those of the present study, making it difficult to establish a parallel with the present results.

Rietmeijer-Mentink et al.25 conducted a comprehensive systematic review study with meta-analysis, which was the basis for this review, mainly regarding how to evaluate study quality. The aforementioned study included the assessment of 35,103 children and adolescents, of whom 11,530 were overweight (32.9%). This proportion was very similar to that found in the present review; however, in that study, 7,191 mothers (62.4%) believed their overweight children had normal weight, different from the proportion found in the present study (90.47%). This difference can be explained by the inclusion of recent studies that demonstrated high levels of underestimation of nutritional status.18,30–32

As most studies that aim to identify the perceptions of parents about the nutritional status of their children are limited to the mother's perception, the present study assessed only the perception of the mother, but a study that addressed the perception of both parents was included, in which it was possible to separate the results related to the mother.33 Several studies could not be included in the present review, since the results of both parents were shown without distinction.34–41

In the majority of the included studies, the mothers’ perception showed high agreement with the actual nutritional status of their children when they had normal weight; however, they tended to significantly underestimate the nutritional status of overweight children.18,23,30,33,42–50 In studies whose results were stratified for overweight and obesity, it was be observed that a higher proportion of underestimated perception of nutritional status occurs when children are obese.30,42,43,47,50 Only two studies observed greater underestimation for overweight children; that by Manios et al.,48 with Greek preschool children aged 2 to 5 years, and the study performed in the United States by Maynard et al.,49 for the age range from 2 to 11 years. However, the reading of these studies did not provide an explanation for this divergence.

It would appear that the mothers would have better perception of the nutritional status of overweight and particularly obese children, considering that, as extreme values, the clinical signs are more visually perceptible;51 however, this is not the case, suggesting that many other factors can be involved in the mother's ability to perceive the nutritional status of their children.

Most studies aimed to investigate the possible factors that lead mothers to incorrectly perceive the nutritional status of their children. In addition to the excess weight of the children themselves, the factors that have the greatest association with poor perception are low maternal education;18,23,30,30,44,48,52 male children,42,48–50 children's age,16,43,49 overweight mother,23,42,43 and ethnicity.44,50 Other factors appeared without repetition, such as the number of children43 and the involvement of children in physical exercise programs.48 In the first case, a larger number of children indicated greater chance of underestimation of nutritional status. In the second case, the participation of children in physical exercise programs increased the chance of the mother's underestimation of the nutritional status of children.

The area or environment also appears to influence how the mother sees her children. In the study of Binkin et al.,30 who assessed the mothers’ perception in regions of Italy with low, moderate, and high prevalence of obesity, there was an association with the region; the highest rates of nutritional status underestimation were observed in the region with the highest prevalence of obesity. Similarly, the study by Rosas et al.,32 which compared the perceptions of mothers in Mexico with mothers from a community of Mexican immigrants in California, demonstrated that only 10.0% of Californian mothers correctly classified their children as were overweight, while 82.0% of those who lived in Mexico correctly assessed the nutritional status of their children.

Given the increasing prevalence of obesity worldwide and in all age groups, it is possible that the mothers perceive overweight in their children and adolescents as a normal condition, especially when the whole family is obese, or when excess weight is something recurrent in the community in which they live.

There is no consensus among studies regarding the tool used to assess the mothers’ perceptions. Among the articles included, three used silhouette scales, in which mothers chose the image they believe best represented the body of the children.18,32,47 The remaining studies used questionnaires in which mothers marked the alternative that best represented the nutritional status of their children, but the way used to represent the nutritional status also varied between these studies.

By simply assessing the results obtained with different tools, it was not possible to identify differences in the mothers’ perception capacity using image scales or questionnaires. However, the study by Lazzeri et al.47 used two instruments to assess the mothers’ perception, and observed that when the silhouette scale was used, 35.0% of the mothers underestimated the nutritional status of their overweight children and 53.0%, of their obese children; when using a questionnaire, the underestimation values increased to 59.0% and 87.0% for overweight and obesity, respectively.

Another point of divergence between studies that could influence the mothers’ accuracy rate is the diagnostic criteria used for nutritional status, since the results obtained by different criteria may be different for the same child or adolescent, as well as studies conducted in different countries.53–57

The most often used criteria for the assessment of nutritional status by BMI, stratified by age and gender, are those of the IOTF,19 CDC,20,21 and WHO.22 In the present review, only one article used a different criterion, defining overweight for children as BMI > 90th percentile.23 Also, only one article used the criteria of the WHO,43 whereas the IOTF criteria appeared in six articles,30,33,44,47,50,52 and the CDC classification was used in nine.16,18,31,32,42,45,46,48,49

The observation of the results analyzed in this review does not allow for the identification of any trends in the mothers’ perception depending on the diagnostic criteria used. No studies comparing the perception of mothers of the nutritional status of their children, determined by different diagnostic criteria were retrieved. However, the meta-analysis by Rietmeijer-Mentink et al.25 demonstrated that the combination of data from different studies showed no statistically significant differences between the scores of sensitivity for different cutoff points used by the three criteria.

In this sense, in the present study, the sensitivity and specificity of maternal perception about the nutritional status of their children were calculated for all studies in which the available data made this analysis possible, totaling ten articles (Table 3). Regardless of the diagnostic criteria used, overall, the studies showed high sensitivity and low specificity, or low capacity of the mother to identify the excess weight in their children and good capacity to identify normal weight for those who had it.

It was observed that most studies concentrated the results and discussion on the underestimation of the nutritional status, as this appears to be the main problem regarding maternal perception. Moreover, most studies observed a low proportion of mothers who overestimate the nutritional status of their eutrophic or overweight children. However, in studies that included children with low weight, most mothers perceived their children as having normal weight.

In the study of Binkin et al.,30 for 37,590 children evaluated, only 3.2% of mothers overestimated their nutritional status; however, for the 344 children who were underweight, 43.2% of their mothers perceived them as having normal weight. In Brazil, the study by Molina et al.50 demonstrated that 2.7% of the mothers overestimated the nutritional status of their children, but when the data referred only to those with low weight, the proportion of underestimation was 26.0%.

In this context, the trend of mothers to overestimate the nutritional status of children with low weight also deserves attention and should be further investigated in studies on this subject.

Considering the quality of the studies reviewed and the results obtained, the present systematic review can contribute to the understanding of aspects related to the mothers’ perception about the nutritional status of their children, as well serve as a basis for further studies in this area.

ConclusionMost studies demonstrated that mothers scarcely perceive the nutritional status of their children, tending to underestimate it, especially in cases of overweight and obesity. This fact deserves attention, since if the excess weight is not noticed, the child or adolescent will not likely be referred to a treatment program, which may contribute to the increasing prevalence of overweight in pediatric populations.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Francescatto C, Santos NS, Coutinho VF, Costa RF. Mothers’ perceptions about the nutritional status of their overweight children: a systematic review. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2014;90:332–43.

Study conducted at the institution Universidade Gama Filho (UGF), Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil.