to meta-analyze studies that have assessed the medication errors rate in pediatric patients during prescribing, dispensing, and drug administration.

Sourcessearches were performed in the PubMed, Cochrane Library, and Trip databases, selecting articles published in English from 2001 to 2010.

Summary of the findingsa total of 25 original studies that met inclusion criteria were selected, which referred to pediatric inpatients or pediatric patients in emergency departments aged 0-16 years, and assessed the frequency of medication errors in the stages of prescribing, dispensing, and drug administration.

Conclusionsthe combined medication error rate for prescribing errors to medication orders was 0.175 (95% Confidence Interval: [CI] 0.108-0.270), the rate of prescribing errors to total medication errors was 0.342 (95% CI: 0.146-0.611), that of dispensing errors to total medication errors was 0.065 (95% CI: 0.026-0.154), and that ofadministration errors to total medication errors was 0.316 (95% CI: 0.148-0.550). Furthermore, the combined medication error rate for administration errors to drug administrations was 0.209 (95% CI: 0.152-0.281). Medication errors constitute a reality in healthcare services. The medication process is significantly prone to errors, especially during prescription and drug administration. Implementation of medication error reduction strategies is required in order to increase the safety and quality of pediatric healthcare.

analisar estudos de meta-análise que avaliaram o índice de erros de medicação em pacientes pediátricos na prescrição, liberação e administração de medicamentos.

Fontes dos dadosforam feitas buscas nas bases de dados Pubmed, Biblioteca Cochrane e Trip, selecionando artigos publicados em inglês de 2001 a 2010.

Síntese dos dadosum total de 25 estudos originais que atenderam aos critérios de inclusão foi selecionado e está relacionado a pacientes pediátricos internados ou pacientes pediátricos nos Serviços de Emergência, com idades entre 0-16 anos. Esses estudos avaliaram a frequência de erros de medicação nas etapas de prescrição, liberação e administração de medicamentos.

Conclusõeso índice combinado de erros de medicação para erros na prescrição/solicitação de medicação foi igual a 0,175 (com intervalos de confiança (IC) de 95%: 0,108-0,270); para erros na prescrição/total de erros de medicação foi 0,342, com IC de 95%: 0,146-0,611; para erros na liberação/total de erros de medicação foi 0,065, com IC de 95%: 0,026-0,154; e para erros na administração/total de erros de medicação foi 0,316, com IC de 95%: 0,148-0,550. Adicionalmente, o índice combinado de erros de medicação para erros na administração/administração de medicamentos foi igual a 0,209, com IC de 95%: 0,152-0,281. Erros de medicação constituem uma realidade nos serviço de saúde. O processo de medicação é significativamente propenso a erros, principalmente na prescrição e administração de medicamentos. Precisa haver a implementação de estratégias de redução dos erros de medicação para aumentar a segurança e a qualidade na prestação de cuidados de saúde pediátrica.

Medication errors constitute a reality in healthcare systems, and are considered to be the most common type of medical errors, according to the Joint Commission.1 The pediatric population is under the risk of medication errors due to the wide variation in body mass, which requires unique drug doses to be calculated, based on the patient's weight or body surface, age, and clinical condition.2 Particularly, medication errors with the potential to cause harm are three times more likely in pediatric inpatients than in adults.3 The great majority of medication errors in children pertain to the stages of prescription and drug administration, according the results of systematic reviews and original studies.3–6

Consequently, according to the National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention, the aim of each healthcare organization should be the constant improvement of its systems in order to prevent harm caused by medication errors.7 Thus, the development of medication error reduction strategies is an important part of ensuring the safety and quality of patient care in pediatric population.8 The aim of this study was to meta-analyze studies that have evaluated the frequency of pediatric medication errors during prescribing, dispensing, and drug administration, in order to highlight the vulnerability to errors of each step, and to improve medication process, leading to error reduction.

MethodsDefinitions termsFor the needs of this meta-analysis, some basic definitions related to the medication errors were used, with the approval of the review of the institution. The definition of medication process includes prescribing, transcribing or documenting, dispensing, administering, and monitoring the patient.9 Medication error is considered as every error during the medication use process.10 Prescribing errors include incomplete, incorrect, inappropriate request at the time of physician order, illegibility and/or need for further interpretation, or any missing route, interval, concentration, rate, dose, and patient data (such as weight, age, or allergies).11 Dispensing error is assumed as any deviation or error deriving from the receipt of the prescription in the pharmacy to the supply of a dispensed medicine to the patient.12 Finally, administration error is defined as any discrepancy occurring between the drug received by the patient and the drug therapy intended by the physician.12

Literature reviewA systematic literature review was conducted from January of 2001 to December of 2010 using the PubMed, Cochrane, and Trip databases, using the key words “medication errors”, “children”, “drug errors”, “pediatric patients”, “medication process”, and “meta-analysis”. The literature search was based on original studies that met the inclusion criteria quoted below:

- •

Studies published in English from January 1, 2001 to December 31, 2010.

- •

Studies that referred to pediatric inpatients or pediatric patients in emergency departments.

- •

Studies that included patients aged 0 to 16 years.

- •

Studies that assessed the frequency of medication errors in the stages of prescribing, dispensing, and drug administration.

- •

Studies that had the same numerators and denominators for the data grouping.

The exclusion criteria involved studies with incomplete data whose clarification was not feasible, despite the researchers’ assistance for the retrieval of required information. Furthermore, the exclusion criteria involved studies that exclusively referred to:

- •

pediatric outpatients;

- •

specific drug categories, such as cardiological and antineoplastics, among others;

- •

specific patient categories, such as oncology; and

- •

adverse drug events (ADEs).

The studies used for this meta-analysis contained clear and unambiguous data related to pediatric medication errors, in these three stages of the process of medication, and described the frequency of medication errors in each stage. The majority of these studies were systematic reviews, and their quality was assessed through the use of two scales. Due to the absence of a universal scale for the quality assessment of observational studies (that constitute the majority of the studies involved in this meta-analysis), and following the recommendations of the meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology guidelines,13 the quality of key design components was assessed separately, and then used to generate a single aggregate score.14 For the measurement of cohort studies quality, a scale of four questions (such as cohort inclusion criteria, exposure definition, clinical outcomes, and adjustment for confounding variables) was used, while each question was scored on a scale of 0 to 2, with a maximum quality score of 8, representing the highest quality score.14

The quality of the one randomized clinical control trial was assessed by a modified Jadad scale with a maximum of 3 points. A maximum of 2 points were earned for the randomization method, and a maximum of 1 point for the description of withdrawals and dropouts.15

Two independent reviewers screened the title and the abstract of each study for their correspondence to the inclusion criteria. In full text articles, two reviewers decided their eligibility, while the relevant information was extracted sequentially, so that the second reviewer was able to study the first reviewer's extracted information.

Statistical AnalysisFor each study, the following error rates were computed from the reported data: prescribing errors to medication orders, prescribing errors to total medication errors, dispensing errors to total medication errors, administration errors to total medication errors, and administration errors to drug administrations. For each error rate, the pooled estimates and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were calculated using the random effects model, due to evidence of significant heterogeneity. Heterogeneity was investigated by use of I2 statistic. Publication bias was tested statistically with Egger's test, which estimates the publication bias by linear regression approach. Analyses were performed using the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software (Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Software) (CMA) (Biostat, Inc.). CMA uses computational algorithms to weight studies by inverse variance. Statistical significance was set at a p-value level of 0.05.

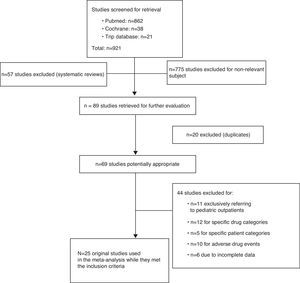

ResultsLiterature searchThrough the systematic literature review, 921 original studies and systematic reviews were identified, while 775 of those were excluded due to the absence of subject relevance, and 57 because they were systematic reviews. 89 studies remained and were evaluated further, while 20 of those were rejected due to the existence of the same studies in different databases. Finally, from the remaining 69 studies, 44 were excluded because they didn’t meet the inclusion criteria. Consequently, 25 original studies were included in this meta-analysis. Fig. 1 represents the flow diagram and provides an overview of the literature review and studies’ selection.

Characteristics of the studiesTable 1 shows the basic characteristics of the 25 studies included in the meta-analysis. In a total of 25 studies, there were nine cohort studies,3,5,11,16–21 three retrospective cohort studies,22–24 seven retrospective studies,4,25–30 two interventional studies,31,32 one quasi-experimental study,33 one cross-sectional study,34 one randomized controlled trial,35 and one observational study.36 Furthermore, the majority of the studies relied on chart review for the data collection (17 of 25),3,5,11,18,20–22,24,26–32,34,35 while four of the 25 studies relied on error reporting systems,4,17,18,23,25 three of 25 studies on observation,16,19,36 and one study on chart review and interviews.33 Regarding the types of medication errors identified through these studies, nine of 25 reported prescribing errors;11,24,26,28,30–33,35 three of 25 studies, administration errors;16,19,36 five of 25 studies, prescribing and administration errors;21,22,29,34 seven studies, all types of medication errors;3–5,17,18,23,25 and one study reported prescribing and dispensing errors.27 Finally, 17 studies referred to pediatric inpatients,3–5,11,16–21,23,25,28,31–32,34,36 seven studies to pediatric patients in emergency departments,22,24,26,29,30,33,35 and one study to pediatric inpatients and patients in emergency departments.27

Characteristics of the studies included in the meta-analysis.

| Studies | StudyDesign | Setting | Duration | Instruments used for the data collection | Error types | Results | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cowley et al.,4 2001USA | Retrospective | PediatricInpatients | 01/1999 –12/2000 | Error reporting system | All types | 143 prescribing errors,449 dispensing errors,1007 administration errors, in a total of 1,956 medication errors | - |

| Kaushal et al.,3 2001USA | Cohort | PICU,Medical/surgicalwards, short-stay medical ward | 04/1999 –05/1999 | Chart review | All types | 454 prescribing errors,6 dispensing errors, 78administration errors, in a total of 616 medication errors | 7 |

| Sangtawesin et al.,25 2003Thailand | Retrospective | PICU, NICU | 09/2001 –11/2002 | Error reporting system | All types | 114 prescribing errors,112 dispensing errors, 49 administration errors, in a total of 322 medication errors | - |

| Kozer et al.,22 2002Canada | Retrospective cohort | Emergencydepartment | 12 randomly days of 2000 | Chart review | Prescribing,administration | 271 prescribing errorsper 1,678 medication orders, 59 administration errors per 1,532 charts | 7 |

| Cimino et al.,31 2004USA | Interventional | PICU | 2 weeks | Chart review | Prescribing | 3,259 errors per 12,026medication orders | - |

| Potts et al.,112004USA | Cohort | PICU | 10/2001 –12/2001(1st phase) | Chart review | Prescribing | 2,049 errors per 6,803medication orders | 6 |

| Prot et al.,162005France | Cohort | PICU, NICU,general pediatric,and nephrologicalunit | 04/2002 –03/2003 | Observation | Administration | 538 errors per 1,719drug administrations | 7 |

| Frey et al.,172002Switzerland | Cohort | PICU | 01/01/2000 –31/12/2000 | Error reporting system | All types | 102 prescribing errors,162 dispensing errors, 200 administration errors in a total of 275 medication errors | 7 |

| Porter et al.,332008USA | Quasi-experimental | Emergencydepartment | 06/2005 –06/2006 | Chart review, interviews | Prescribing | 1,755 errors per 2,234medication orders | - |

| Taylor et al.,26 2005USA | Retrospective | Emergencydepartment | 01/1998 -06/1998 | Chart review | Prescribing | 311 errors per 358medication orders | - |

| Wang et al.,182007USA | Cohort | PICU, NICU,pediatric ward | 02/2002 –04/2002 | Chart review, error reporting system | All types | 464 prescribing errors,2 dispensing errors, 101administration errors in a total of 865 medication errors | 6 |

| King et al.,232003Canada | Retrospectivecohort | Medical andsurgicalward | 04/1993 –03/1996(1st phase) | Error reporting system | All types | 13 prescribing errors,19 dispensing errors, 314 administration errors in a total of 416 medication errors | 7 |

| Kozer et al.,352005Canada | Randomizedcontrolclinical trial | Emergencydepartment | 07/2001 | Chart review | Prescribing | 68 errors per 411medication orders | 3(Jadadscore) |

| Otero et al.,342008Argentina | Cross-sectional | ICU, NICUpediatricsclinic | 06/2002(1st phase) | Chart review | Prescribing,administration | 102 prescribing errorsper 590 medication orders99 administration errors per 1,174 drug administrations | - |

| Fortescueet al.,5 2003USA | Cohort | PICU, NICU,short-stay medicalward, medical/surgical ward | 04/1999 –05/1999 | Chart review | All types | 479 prescribing errors,6 dispensing errors, 79administration errors in atotal of 616 medication errors | 5 |

| Chua et al.,192010Malaysia | Cohort | Pediatric ward | 11/2004 –01/2005 | Observation | Administration | 100 errors per 857drug administrations | 5 |

| Ghaleb et al.,20 2010UK | Cohort | PICU, NICUmedical andsurgicalward | 2004-2005for 22weeks | Chart review | Prescribing,administration | 391 prescribing errorsper 2,955 medication orders429 administration errors per 1,544 drug administrations | 5 |

| Fontan et al.,21 2003France | Cohort | NephrologicalUnit | 02/1999 –03/1999 | Chart review | Prescribing,administration | 937 prescribing errorsper 4,532 medication orders1077 administration errors per 4,135 drug administrations | 6 |

| Raja Lope et al.,36Malaysia | Observational | NICU | 02/2005(1st phase) | Observation | Administration | 59 errors per 188 drugadministrations | - |

| Sard et al.,242008 USA | Retrospectivecohort | Emergencydepartment | 2005 | Chart review | Prescribing | 101 errors per 326medication orders | 7 |

| Jain et al.,272009 India | Retrospective | PICU, Emergencydepartment | 01/2004 –04/2004 | Chart review | Prescribing,dispensing | 67 prescribing errors &14 dispensing errorsper 821 medication orders | - |

| Kadmonet al.,28 2009Israel | Retrospective | PICU | 09/2001(1st phase) | Chart review | Prescribing | 103 errors per 1,250medication orders | - |

| Larose et al.,29 2008Canada | Retrospective | Emergencydepartment | 2003(1st phase) | Chart review | Prescribing,administration | 32 prescribing errors &23 administration errors per 372 medication orders | - |

| Rinke et al.,302008USA | Retrospective | Emergencydepartment | 04/2005 –09/2005 | Chart review | Prescribing | 81 errors per 1,073medication orders | - |

| Campinoet al.,32 2009Spain | Interventional | NICU | 09/2005-02/2006 | Chart review | Prescribing | 868 errors per 4,182medication orders | - |

PICU, pediatric intensive care unit; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit

In studies in which there was intervention,5,11,17–18,21,23–24,28,29,31–36 data was obtained from phase I only, as presented in Table 1.

Therefore, great heterogeneity between the studies was observed, due to the difference in parameters and conditions used for the data collection. Significant heterogeneity was observed in the manner that medication errors and their categories were defined by each study. Namely, there were studies in which administration errors included every error from the stage of drug dispensing in the ward by the nursing staff to drug administration, such as those by Chua et al.,19 Fontan et al.,21 and Jain et al.27 These studies, in this meta-analysis, were classified in the category of administration errors. In other studies, dispensing errors were defined as errors during drug dispensing by the pharmacist.5,8,17,18,23,25

Difference was also noticed between the definitions of prescribing errors across the studies. While the majority of the studies used the broadest sense of the term “prescribing error”,20,24,26,29,32–34 as the one used for this meta-analysis, there were studies that used the term prescribing error solely as any incomplete or ambiguous order.11,28

Moreover, there was a differentiation in the instruments used for the data collection by each study, the studies’ design, the age groups that took part in each study, the settings, and the numerators and denominators used by each study for the assessment of the frequency of medication error occurrence.

Statistical ResultsFor the purposes of this study, five groups based on common numerators and denominators were combined. The numerator and the denominator of each study constitute the estimated relative measure. Through the use of the estimated relative measure (numerator/denominator) of each study, integrated error rates were calculated for each of these groups. Most studies participated in more than one group. The first group, specifically, included prescribing errors in relation to the medication orders. The prescribing errors were defined as numerators and the medication orders as denominators. The prescribing error rate per medication orders was calculated as 0.175 (95% CI: 0.108-0.270; p-value<0.001). The second group related to prescribing errors (numerator) and total medication errors (denominator). The integrated prescribing error rate was 0.342 (95% CI: 0.146-0.611; p-value=0.246). The third group included dispensing errors (numerator) and total medication errors (denominator). The total dispensing error rate was estimated as 0.065 (95% CI: 0.026-0.154; p-value<0.001). The fourth group consisted of administration errors as numerator and total medication errors as denominator, with a total administration error rate of 0.316 (95% CI: 0.148-0.550; p-value=0.119). Finally, the fifth group contained administration errors per drug administration. The integrated administration error rate was 0.209, (95% CI: 0.152-0.281; p-value<0.001).

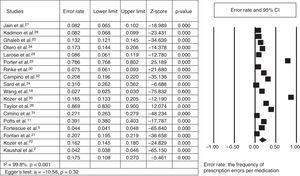

Prescribing errors per medication ordersEighteen studies were used for this group. Nine of 18 studies referred exclusively to prescribing errors;11,26,30–33,35 five of 18, to prescribing and administration errors;20–22,29,34 one of 18, to prescribing and dispensing errors;27 and three of 18, to all types of errors.3,5,18 Furthermore, all studies comprised by this group clearly described the number of medication orders, screened for prescribing errors. On Fig. 2, all 18 studies are represented, as well as the error rates of each study (from the ratio of prescribing errors per medication orders of each study) and the random effect rate. In a total of 78,135 medication orders from these 18 studies, the integrated error rate was calculated as 0.175, (95% CI: 0.108-0.270;and p-value<0.001). In Fig. 2, the forest plot is illustrated. The vertical axis of the forest plot represents the studies, while the horizontal axis, the estimated relative measures. Squares illustrate the estimated relative measures of each study and the diamond, the integrated error rate calculated through the random effect model.

No potential publication bias was found by Egger's test (intercept a=−0.400;95% CI: -1.594 to 0.792; p=0.443).

Moreover, the heterogeneity between the studies was very high, as investigated by the I2 statistic (I2=99.8%; p<0.001).

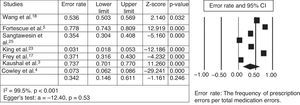

Prescribing errors per total medication errorsIn this group, seven studies3,4,17,18,23,25 concerning all types of errors with the inclusion of prescribing errors were included. Fig. 3 provides an overview of the referred studies with their error rates. The integrated prescribing error rate estimated in a total of 5,066 medication errors from these seven studies was 0.342 (95% CI: 0.146-0.611; p-value=0.246).Additionally, in the forest plot, the significant heterogeneity between the studies is illustrated, as the estimated relative measures of each study (squares) are distributed heterogeneously around the integrated error rate (diamond). No potential publication bias was found by Egger's test (intercept a=-12.40; 95% CI: -60.19 to 35.39; p>0.05), and very high heterogeneity as I2>50% (I2=99.5%; p<0.001).

Dispensing errors per total medication errorsThe same seven studies3,4,17,18,23,25 used for this group refer to all types of errors, including dispensing errors. An overview of the studies and the forest plot is showcased in Fig. 4. The integrated dispensing error rate was 0.065 (95% CI: 0.026-0.154; p-value<0.001). Consequently, in a total of 5,066 medication errors, the random effect rate was measured to 6.5%.

No potential publication bias was found by Egger's test (intercept a=-6.50; 95% CI: -18.17 to 5.15; p=0.21), and very high heterogeneity as I2>50% (I2=98.6%; p<0.001).

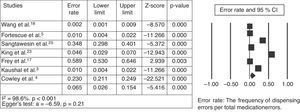

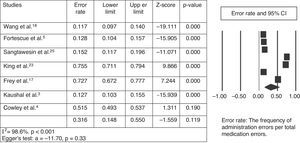

Administration errors per total medication errorsThe same seven studies3,4,17,18,23,25 included in this group reported all types of medication errors, as well as dispensing errors. Fig. 5 shows the estimated relative measures for each study, and the forest plot presents the distribution of the studies around the integrated error rate. The administration error rate was 0.316 (95% CI: 0.148-0.550; p-value=0.119). Thus, in a total of 5,066 medication errors, the random effect rate was 31.6%.

No potential publication bias was found by Egger's test (intercept a=-11.70; 95% CI: -39.90 to 16.49; p=0.33), and very high heterogeneity as I2>50% (I2=98.6%, p<0.001).

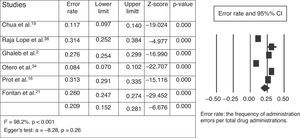

Administration errors per drug administrationsSix studies16,19–21,34,36 with common numerators (administration errors) and denominators (drug administrations) were chosen for this group. For each study, the estimated relative measures were calculated, as well as the integrated administration error rate, which measured 0.209 (95% CI: 0.152-0.281; p-value<0.001). Fig. 6 provides an overview of the ratios of administration errors per drug administration and the forest plot that illustrates the studies’ contribution to the value of the integrated error rate. In a total of 9,167 drug administrations, from these six studies, the random effect error rate was as 20.9%.

No potential publication bias was found by Egger's test (intercept a=-8.28; 95% CI: -25.95 to 9.38; p=0.26), and very high heterogeneity as I2>50% (I2=98.2%; p<0.001).

DiscussionMedication errors cause serious problems in daily clinical practice and are of significant concern, especially for the pediatric population. Many of the members of the disciplinary team may be involved in the causation of medication errors, such as clinicians, nurses, pharmacists, although there is great speculation regarding their management and reduction. In this meta-analysis, the authors tried to estimate a more integrated result in relation to the frequency and nature of medication errors in pediatric patients, during the stages of prescribing, dispensing, and administration. For this objective, five different groups were created, after a careful selection of studies that met the goals of each group. Therefore, the integrated rate in relation to the prescribing errors per medication order was calculated as0.175, and in relation to the prescribing errors per total medication errors, dispensing errors per total medication errors, and administration errors per total medication errors were calculated as 0.342, 0.065, and 0.316, respectively. Moreover, the integrated rate for the ratio of administration errors per drug administration was estimated as 0.209.

This study highlighted the most vulnerable stages in the medication use process. The highest rates were observed in prescribing and drug administration, managed by clinicians and nurses, respectively. Additionally, comparing the results between the groups, the predominance of prescribing errors can be discerned, followed by administration errors; dispensing errors had the lowest rates. Due to the absence of other meta-analyses in relation to medication errors in children, it's impossible to compare the results with other studies. Therefore, because of the occurrence of systematic reviews, the two stages of medication process (prescribing and administration) present the highest error rates, as shown in the study by Miller et al., in which prescribing errors varied between 3% and 37% and administration errors between 72% and 75%.6 Moreover, according to the review of eight studies, which used observation for administration error identification, Ghaleb et al. highlighted administration error rates per drug administration of 0.6% to 27%.2 These rates agree with that of the present meta-analysis, which was calculated as 20.9%. Moreover, Miller et al. estimated that 5% to 27% of medication orders for children contained an error throughout the entire medication process, involving prescribing, dispensing, and administration, based on three studies;6 in the current meta-analysis, the integrated error rate for prescribing errors per medication order approached 17.5%.

Dispensing errors, conversely, presented the lowest rate (6.5%), in contrast to the other two stages of the medication use process. However, in the study by Miller et al., the dispensing error rates ranged between 5% and 58%, as calculated through the use of three studies, due to the heterogeneity presented in the others studies.6

The use of I2 statistic showcased significant heterogeneity between the studies, as I2 was >50% in all five groups. This heterogeneity is reflected in the forest plots of each group, with the heterogeneous distribution of the studies around the integrated error rate. Furthermore, Egger's test indicated the absence of potential publication bias.

The members of the disciplinary team manage the medication delivery system and as a result, they become involved in medication errors of pediatric patients. A medication error is not the direct result of a sole member of the disciplinary team's misconduct, and the accusation of that person should not be pursued or recognized as a reward for reporting the error. The awareness of the existence of medication errors in clinical daily practice, as well as the interactive nature of the medication use process, with the participation of all members of the disciplinary team, leads to a better understanding of the errors. Consequently, the results of this meta-analysis offer useful information for healthcare professionals, as they provide the opportunity of understanding the nature and frequency of medication errors, and the ability to re-evaluate and improve the medication process.

Furthermore, the existence of integrated error rates, related to medication errors in pediatric patients, can contribute to the understanding of the nature, frequency, and consequences of medication errors, as well as the necessity of the development of medication error reduction strategies, staff education, and clinical protocols and guidelines.

LimitationsThe evaluation of the heterogeneity and the identification of its causes constitute parallel limitations of this meta-analysis. The selection of the studies solely published in English was a limitation, as well as the heterogeneity of the studies.

The heterogeneity emanates from the variety of the studies’ characteristics. Initially, the different error definition, as previously mentioned, complicated the studies’ grouping. Another reason was the different conditions under which each study took place. Emergency departments, for example, represented higher prescribing error rates,22,27,29,33 while pediatric intensive care units and neonatal intensive care units presented high rates in all types of medication errors.11,16–18,25,31,32,34,36

There was also a variation in the studies’ design (cohort, randomized controlled trial, cross-sectional, retrospective, interventional), as well as in the age groups that took part in each study. Some of the age groups, such as neonates, may be more vulnerable to medication errors than preschool or school age children, due to their organic prematurity, the very small amounts of therapeutic drug doses, or their serious clinical condition.

The denominators that each study used for the determination of error frequency vary. Certain studies used handwritten orders or computerized orders as denominators, while others were based on drug administrations. Computerized orders are more susceptible to the recognition of prescribing errors, in contrast to handwritten orders, where the identification of the error is at the disposal of the researcher or the professional who reported the error. Finally, there was a variety in the instruments that each study used for the data collection. Some studies used chart reviews or observation, while others used error-reporting systems, thus minimizing the possibility of recognizing more errors, in contrast to using a combination of those instruments.6

In conclusion, medication errors in pediatric patients constitute a daily phenomenon in hospitals. Through this meta-analysis, it has been ascertained that the stages of prescription and administration were more prone to errors, as they demonstrated higher rates than the stage of dispensing. The stage of dispensing had the lowest error rates, with the pharmacist responsible for medication dispensing in the majority of the studies.

The results of this meta-analysis highlight the necessity to improve the way that both clinicians and nurses are managing the medication process during the pediatric care delivering. Furthermore, the communication between the members of the multidisciplinary team regarding medication errors in children should be focused on adoption of common definitions for medication errors and their categories, staff education in recognizing medication errors, and implementation of error reporting in daily clinical practice.

The establishment of medication error reduction strategies should constitute a goal for all healthcare institutions and a stimulus for the improvement of the pediatric care delivery.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Koumpagioti D, Varounis C, Kletsiou E, Nteli C, Matziou V. Evaluation of the medication process in pediatric patients: a meta-analysis. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2014;90:344–55.