This study aimed to identify markers of metabolic syndrome (MS) in patients with phenylketonuria (PKU).

MethodsThis was a cross-sectional study consisting of 58 PKU patients (ages of 4-15 years): 29 patients with excess weight, and 29 with normal weight. The biochemical variables assessed were phenylalanine (phe), total cholesterol, HDL-c, triglycerides, glucose, and basal insulin. The patients had Homeostasis Model Assessment (HOMA) and waist circumference assessed.

ResultsNo inter-group difference was found for phe. Overweight patients had higher levels of triglycerides, basal insulin, and HOMA, but lower concentrations of HDL-cholesterol, when compared to the eutrophic patients. Total cholesterol/HDL-c was significantly higher in the overweight group. A positive correlation between basal insulin level and HOMA with waist circumference was found only in the overweight group.

ConclusionThe results of this study suggest that patients with PKU and excess weight are potentially vulnerable to the development of metabolic syndrome. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct clinical and laboratory monitoring, aiming to prevent metabolic changes, as well as excessive weight gain and its consequences, particularly cardiovascular risk.

Determinar marcadores bioquímicos da síndrome metabólica em pacientes com PKU.

MétodosForam avaliados dois grupos de pacientes com PKU, 4 a 15 anos de idade, com excesso de peso (29) e eutróficos (29). As variáveis bioquímicas avaliadas foram a fenilalanina (phe), colesterol total, HDL-c, triglicérides, glicose e insulina basal. Foi determinado o HOMA e mensurada a circunferência da cintura.

ResultadosAs concentrações de phe, de colesterol total e de glicose foram equivalentes entre os grupos. Os pacientes com excesso de peso apresentaram maiores concentrações de triglicérides, de insulina basal, maiores valores da determinação do HOMA, menores concentrações de HDL colesterol e valores mais elevados da relação do colesterol total/HDL-c. Houve correlação positiva entre a dosagem de insulina basal e do HOMA com a circunferência da cintura nos pacientes do grupo com excesso de peso.

ConclusõesOs resultados deste estudo sugerem que pacientes com PKU e excesso de peso são potencialmente vulneráveis ao desenvolvimento da síndrome metabólica. Há, portanto, necessidade de acompanhamento clínico-laboratorial que previna as alterações metabólicas, o ganho excessivo de peso e as suas consequências, em especial o risco cardiovascular.

Phenylketonuria (PKU), an inborn error of amino acid metabolism characterized by the loss or reduction in the activity of hydroxylase phenylalanine (phe) enzyme, leads to elevated blood levels of phe and its metabolites, resulting in neurological damage that culminates in irreversible mental retardation.1,2 Disease control is accomplished by prescribing a diet free of animal protein and with restricted vegetable protein consumption. Due to the diet characteristics, some researchers have associated PKU to a tendency of excessive weight gain and metabolic syndrome (MS).3–6 Conversely, excess weight and metabolic alterations associated with it have been associated to increased cardiovascular risk, which has prompted researchers worldwide to consider the importance of early identification and damage prevention in at-risk populations.7–11

Due to the particularities of their diet, PKU patients can be considered a vulnerable group to metabolic abnormalities and excess weight. Protein restriction favors – and even stimulates – the consumption of carbohydrate-rich foods (especially simple carbohydrate) and lipids, in particular, increasing the risk of weight gain.

MS would be present in this population due to both the diet and the disease itself. The detection of parameters that identify the presence of MS may prevent the emergence of other diseases in these patients, for instance, diabetes and cardiovascular disease. The International Diabetes Federation (IDF) considers the measurement of waist circumference (WC), associated with the measurements of HDL cholesterol (HDL-c), triglycerides (TG), and glucose to be parameters for the identification of MS. The latter would be defined by WC measurements > 90th percentile, associated with at least two of the following findings: high levels of TG, reduced HDL-c, and increase in blood pressure and fasting glucose.11

This study sought to determine some markers of MS in patients with PKU treated at the Special Genetics Department of Hospital das Clinícas, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (SEG-HC-UFMG), to identify risks and to promote better clinical and laboratory control of the disease and the adoption of special protocols for preventing cardiovascular damage.

MethodsA study of case series involving 58 children and adolescents with PKU, aged 4 to 15 years was conducted. Data collection was performed between October of 2008 and November of 2009. Patients were selected, scheduled, and submitted to clinical and laboratory assessment.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (COEP-UFMG). An informed consent was signed by a parent, legal guardian, and/or PKU patient older than 6 years old, after due explanations.

The groups were defined according to the body mass index (BMI) calculated according to the formula: BMI=weight (kg)/height2 (m). The value obtained was assessed using the growth curves of the World Health Organization (WHO) for children aged 0-5 years (2006) and 5-19 years (2007), considering as cutoffs for overweight and obesity BMI > 85th percentile and > 97th percentile, respectively. The groups were constituted as follows: 29 patients with normal weight and 29 with excess weight.

Measures of waist circumference were analyzed in accordance with the percentile suggested by MacCarthy et al.7

As for the laboratory tests, patients underwent a 10-hour fast, with a maximum of 14hours of fasting. Serum concentrations of fasting phe, total cholesterol (TC), HDL-c, triglycerides, glucose, and basal insulin were determined. Lipid and glucose levels were analyzed enzymatically, using the dry chemical technique. Insulin resistance was calculated using the mathematical model of Matthews et al.12 Lipid measurements were conducted in accordance with the I Guideline of Atherosclerosis in Childhood and Adolescence.13 The mean phe (control phe) was determined by the arithmetic mean of the last 12 measurements and was considered inadequate when higher than the maximum reference value for the age range.14 Phe levels were obtained by ultramicrofluorometry, using the ultramicro-fluorometric test (UMTEST PKU).15

The results obtained were stored, tabulated in an electronic spreadsheet, and analyzed using SPSS, release 15.0. Sample distribution was verified by the Shapiro-Wilk's test. Student's t-test was used for variables with normal distribution, whereas the nonparametric Mann Whitney test was used for those with non-normal distribution. The association analysis was performed using Pearson's chi-squared test and correlation analysis using Spearman's test.

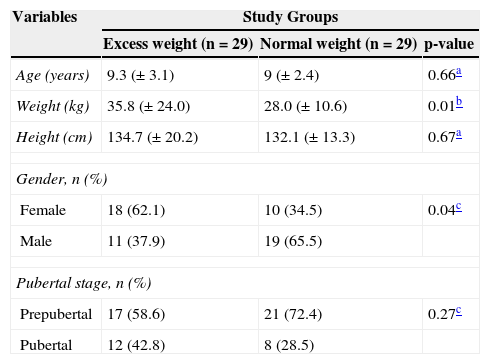

ResultsTable 1 describes the anthropometric characteristics, gender distribution, and pubertal stage of each group.

Characterization of two groups of phenylketonuria patients aged 4 to 15 years that participated in the study.

| Variables | Study Groups | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Excess weight (n=29) | Normal weight (n=29) | p-value | |

| Age (years) | 9.3 (± 3.1) | 9 (± 2.4) | 0.66a |

| Weight (kg) | 35.8 (± 24.0) | 28.0 (± 10.6) | 0.01b |

| Height (cm) | 134.7 (± 20.2) | 132.1 (± 13.3) | 0.67a |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Female | 18 (62.1) | 10 (34.5) | 0.04c |

| Male | 11 (37.9) | 19 (65.5) | |

| Pubertal stage, n (%) | |||

| Prepubertal | 17 (58.6) | 21 (72.4) | 0.27c |

| Pubertal | 12 (42.8) | 8 (28.5) | |

The groups showed similar results in relation to blood phe control. There was no significant difference (p=1) in mean phe levels of the individual: 50% of the tests were adequate in both groups. Regarding the phe levels collected after fasting (p=0.14), 58.6% of tests were adequate in the excess weight group and 41.4% in the normal weight group.

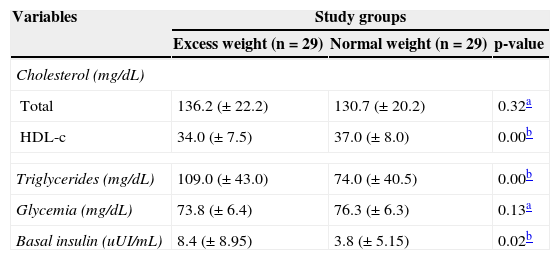

Patients from the excess weight group had higher basal triglyceride and insulin levels, but lower HDL-cholesterol, when compared to normal weight individuals (Table 2).

Blood levels of total cholesterol and HDL-c, triglycerides, blood glucose, and basal insulin in phenylketonuria patients with excess weight and normal weight.

| Variables | Study groups | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Excess weight (n=29) | Normal weight (n=29) | p-value | |

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) | |||

| Total | 136.2 (± 22.2) | 130.7 (± 20.2) | 0.32a |

| HDL-c | 34.0 (± 7.5) | 37.0 (± 8.0) | 0.00b |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 109.0 (± 43.0) | 74.0 (± 40.5) | 0.00b |

| Glycemia (mg/dL) | 73.8 (± 6.4) | 76.3 (± 6.3) | 0.13a |

| Basal insulin (uUI/mL) | 8.4 (± 8.95) | 3.8 (± 5.15) | 0.02b |

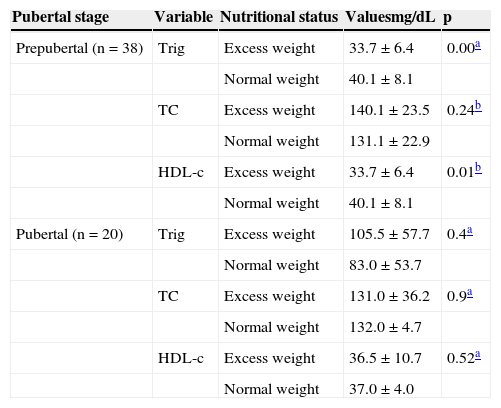

The patients’ lipid profile, when analyzed according to pubertal stage, showed higher triglyceride and lower HDL-c levels in the group of prepubertal patients with excess weight. No statistically significant differences were observed between the two groups of patients at pubertal stage (Table 3).

Comparison between the mean or median of serum levels of triglycerides, total cholesterol, and HDL-c in phenylketonuria patients with normal weight and excess weight, according to pubertal stage.

| Pubertal stage | Variable | Nutritional status | Valuesmg/dL | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prepubertal (n=38) | Trig | Excess weight | 33.7±6.4 | 0.00a |

| Normal weight | 40.1±8.1 | |||

| TC | Excess weight | 140.1±23.5 | 0.24b | |

| Normal weight | 131.1±22.9 | |||

| HDL-c | Excess weight | 33.7±6.4 | 0.01b | |

| Normal weight | 40.1±8.1 | |||

| Pubertal (n=20) | Trig | Excess weight | 105.5±57.7 | 0.4a |

| Normal weight | 83.0±53.7 | |||

| TC | Excess weight | 131.0±36.2 | 0.9a | |

| Normal weight | 132.0±4.7 | |||

| HDL-c | Excess weight | 36.5±10.7 | 0.52a | |

| Normal weight | 37.0±4.0 |

Trig, triglycerides; TC, total cholesterol.

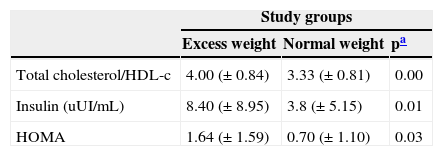

The group with excess weight had significantly higher values of total cholesterol/HDL-c ratio, blood levels of basal insulin, and HOMA determination (Table 4).

Comparison between total cholesterol/HDL-c, blood levels of basal insulin, and HOMA in phenylketonuria patients with excess weight and normal weight.

| Study groups | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Excess weight | Normal weight | pa | |

| Total cholesterol/HDL-c | 4.00 (± 0.84) | 3.33 (± 0.81) | 0.00 |

| Insulin (uUI/mL) | 8.40 (± 8.95) | 3.8 (± 5.15) | 0.01 |

| HOMA | 1.64 (± 1.59) | 0.70 (± 1.10) | 0.03 |

There was a positive correlation between basal insulin level (p=0.00) and HOMA (p=0.08) with WC, but only in the group with excess weight.

DiscussionExcess weight is a current public health problem in many parts of the world. In Brazil, despite prevention programs undertaken by health managers and professionals, prevalence rates have increased in all age groups.16

The concern for obesity in PKU patients resulted from the routine observation of clinical care to patients in SEG-HC/UFMG, confirmed by assessments performed in 2007 and 2009.

Cross-sectional investigations identified increasing prevalence rates of excess weight and obesity, going from 16.8% and 8.8% in 2007 to 19.8% and 9.6% in 2009, respectively.

The occurrence of excess weight in a population with PKU, whose diet is periodically monitored by nutritionists, has one of its possible justifications in the restrictive and monotonous character of the diet, especially for older children and adolescents, who have autonomy in dietary choices.

Dietary transgressions cause variations in the laboratory control of the disease starting at this age group and metabolic abnormalities that, in the medium term, can translate into excessive weight gain and increased cardiovascular risk. Several studies confirmed these control difficulties in patients that acquired dietary autonomy.17–20 In this study, the group of overweight patients was expected to have higher concentrations of blood phe – due to dietary transgressions – as reported by McBurnie et al.,3 which could explain the excess weight in these patients. However, it was verified that most mean blood phe tests were elevated in both groups and that the excess weight group showed a higher number of adequate tests for the variable fasting phe.

Belanger-Quintan et al.5 and Rocha et al.20 suggested that the excess weight of PKU patients was related to disease severity. As in the present study most of the participants in both groups had the severe form of the disease, it was not possible to correlate excess weight with disease severity. Therefore, it appears that the excess weight detected in these patients is not necessarily related to food transgression or disease severity.

Non-adherence to or inadequacy of nutritional guidelines for the treatment of PKU can cause abnormalities resulting from lack or excess of nutrients,21–24 and excess weight (and its consequences) is the most frequent. Thus, as demonstrated by Freedman et al.,25 patients with excess weight evaluated in this study showed a positive correlation between measures of WC and levels of basal insulin and HOMA determinations.

The low concentrations of cholesterol observed in this study may be explained by genetic factors, by cholesterol biosynthesis inhibition, and also by an exclusive vegetarian diet.10,26–29 PKU patients with excess weight, in addition to central obesity expressed by the WC, had high blood concentrations of triglycerides and reduced HDL-c, suggesting the presence of MS.11 Low concentrations of HDL-c and high concentrations of LDL-c, even isolated, have been considered as good predictors of cardiovascular risk.29,30

According to Burrows et al.,8 children and adolescents have a three-fold higher risk of developing MS when basal insulin and HOMA are > 75th percentile. In this study, a higher percentage of patients with high levels of basal insulin and HOMA was identified among those with excess weight and at pubertal stage (31% vs. 14%). Dietary characteristics of PKU patients associated with the physiological changes of puberty may explain these findings, which should constitute warning factors for the diagnosis of MS. The WHO (World Health Organization)31 and EGIR (European Group for the Study of Insulin Resistance)32 consider insulin resistance to be one of the markers of MS. In patients with PKU and excess weight, elevated HOMA values were also found.

As in the study by Rocha et al.,20 the present results demonstrate that patients with PKU and excess weight behave similarly to obese individuals without a genetic disease. However, PKU patients with excess weight may be more susceptible to MS due to factors inherent to the disease. Thus, a review of the treatment protocol used for these patients is advisable, characterized by the introduction of simple procedures that can be conducted in any outpatient care facility. General guidelines should emphasize the need to maintain the food free of phe, control the over-consumption of sugar, as well as the importance of incorporating physical activity into everyday life, as appropriate to each individual. Clinical control must include regular measurement of WC and, when necessary, monitoring of blood concentrations of cholesterol, triglycerides, glucose, and basal insulin.

Patients with excess weight showed higher blood concentrations of triglycerides and basal insulin, higher values of total cholesterol/HDL-C ratio and HOMA and lower HDL-c levels. The results of this study suggest that patients with PKU and excess weight are potentially vulnerable to the development of MS. It is, therefore, necessary to conduct clinical and laboratory monitoring to prevent metabolic changes, as well as excessive weight gain and its consequences, particularly cardiovascular risk. Additionally, specific dietary guidelines should be emphasized in clinical practice, especially for patients with excess weight, in order to prevent metabolic inadequacies.

FundingFAPEMIG (Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do estado de Minas Gerais).

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Kanufre VC, Soares RD, Alves MR, Aguiar MJ, Starling AL, Norton RC. Metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents with phenylketonuria. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2015;91:98–103.

Study conducted at Núcleo de Ações e Pesquisa em Apoio Diagnóstico (NUPAD), Hospital das Clínicas, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG), Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil.