This systematic review of national or regional guidelines published in English aimed to better understand variance in pre-hospital and emergency department treatment of status epilepticus.

SourcesSystematic search of national or regional guidelines (January 2000 to February 2017) contained within PubMed and Google Scholar databases, and article reference lists. The search keywords were status epilepticus, prolonged seizure, treatment, and guideline.

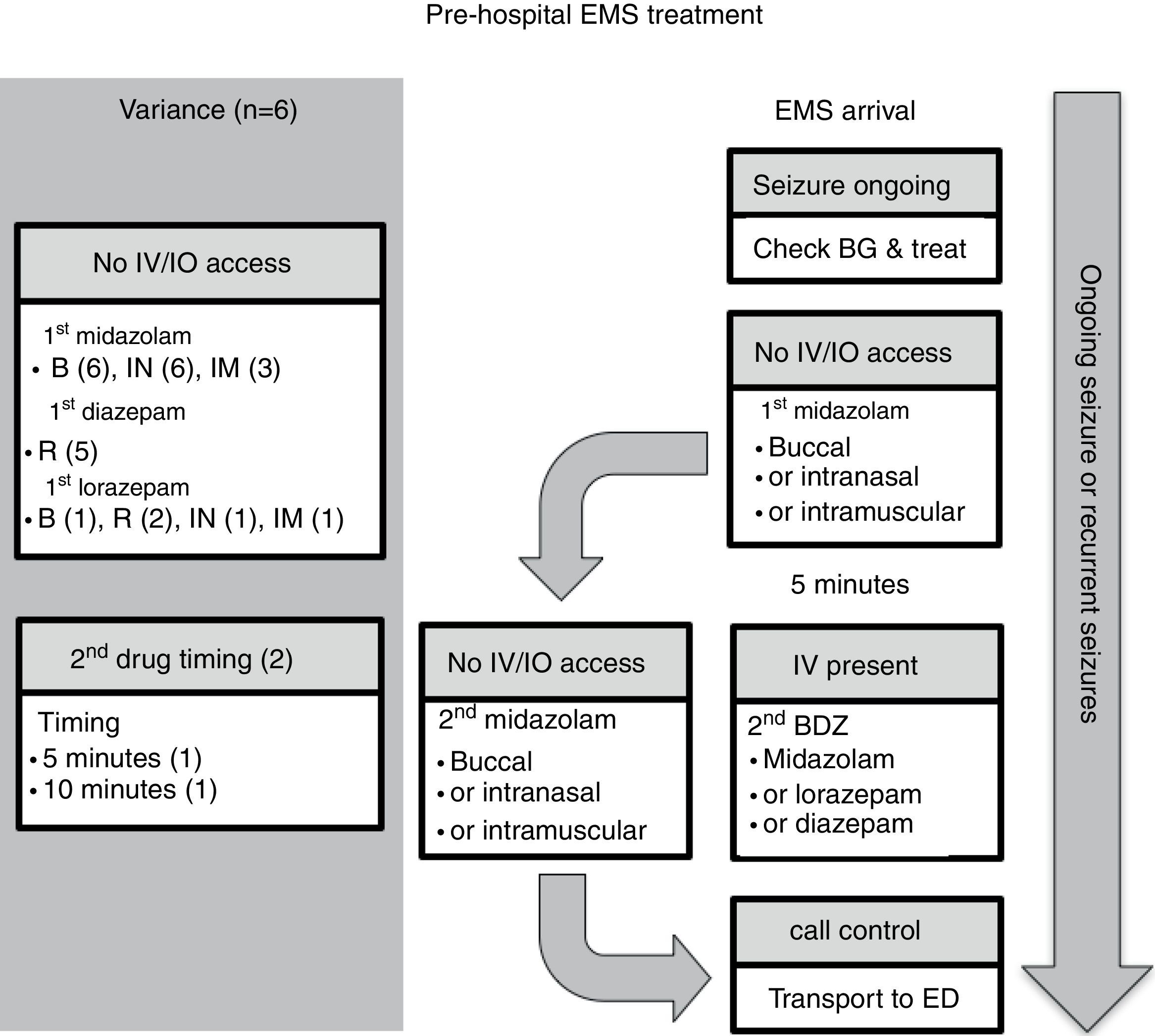

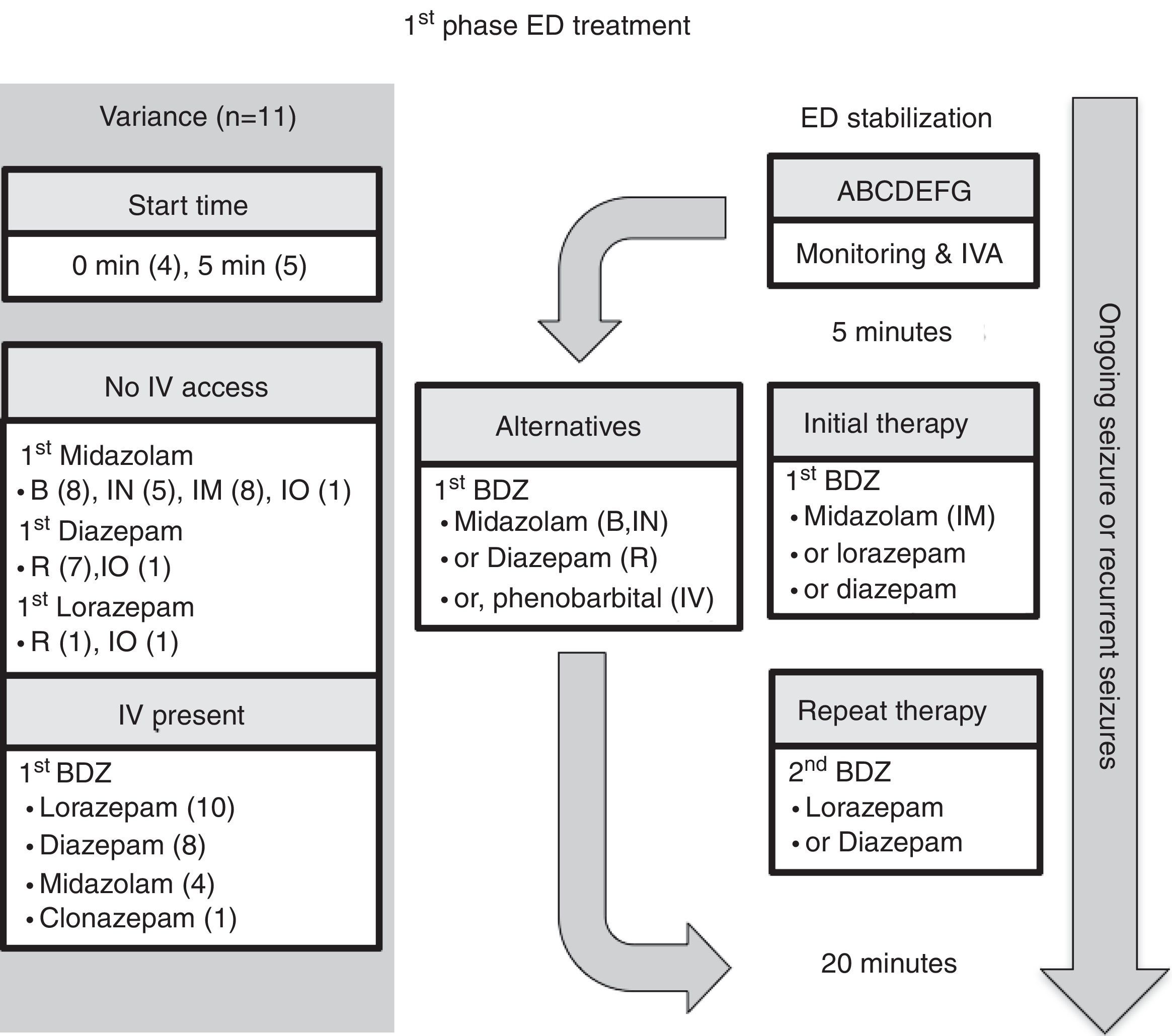

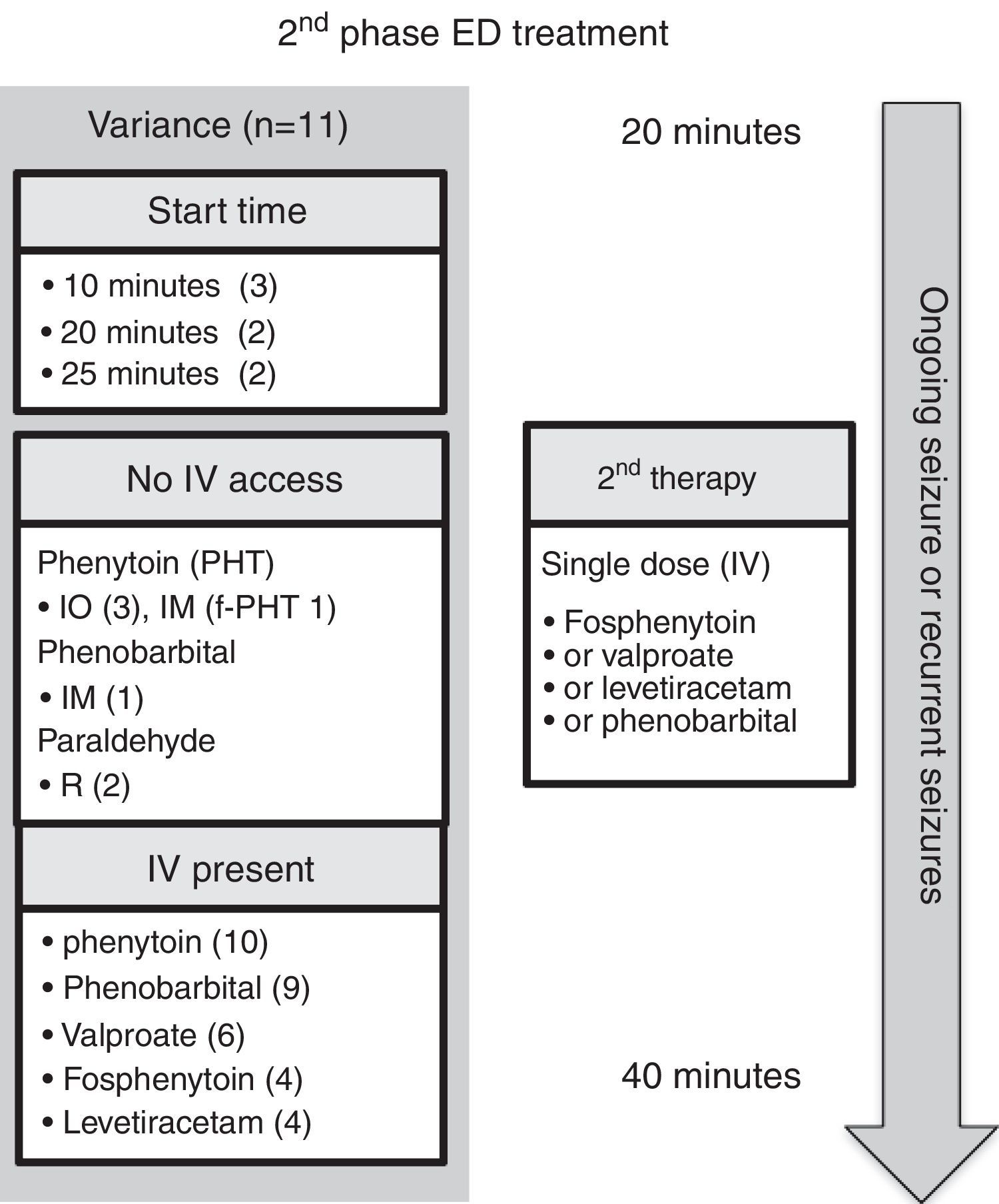

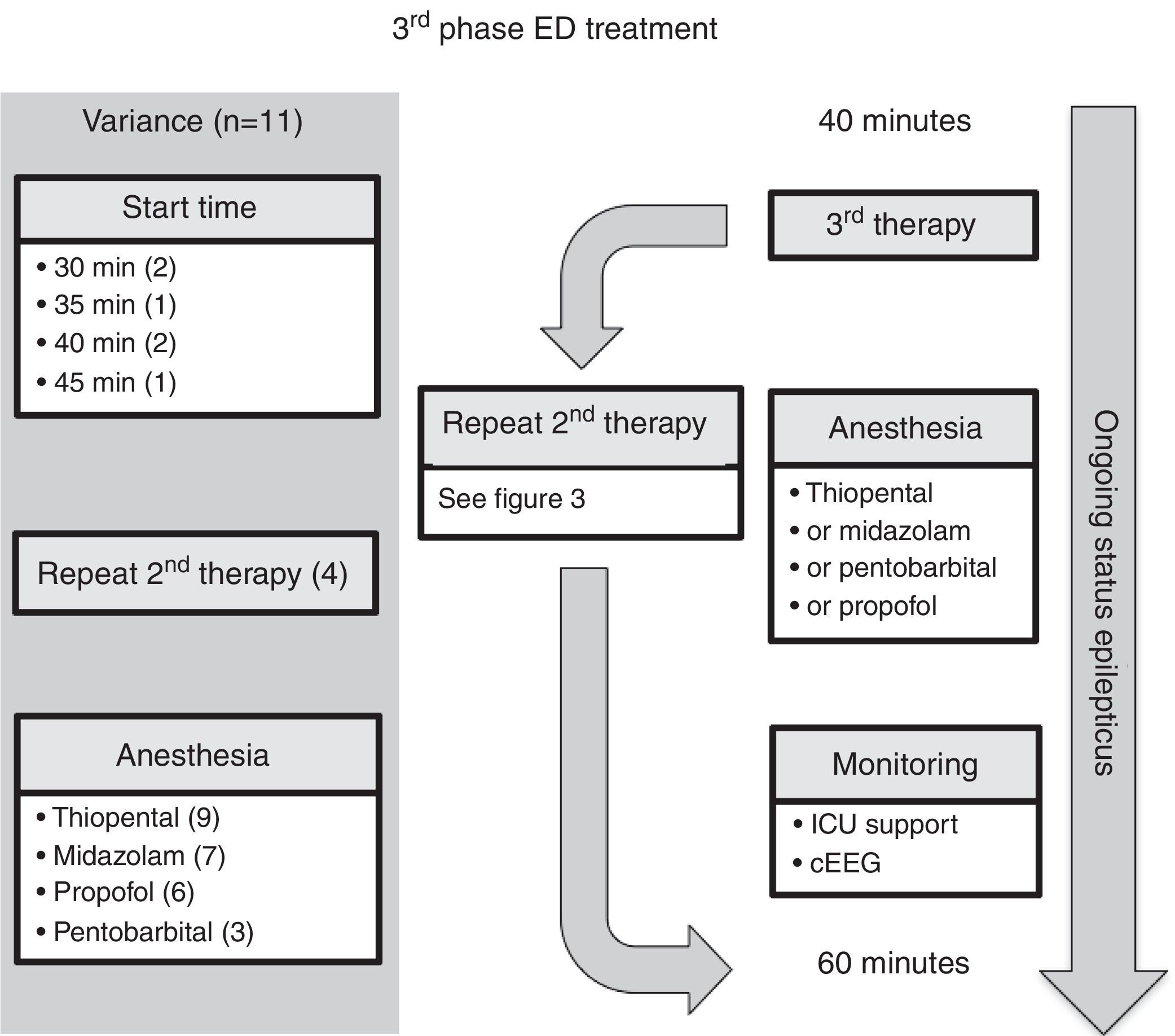

Summary of findings356 articles were retrieved and 13 were selected according to the inclusion criteria. In all six pre-hospital guidelines, the preferred route of medication administration was to use alternatives to the intravenous route: all recommended buccal and intranasal midazolam; three also recommended intramuscular midazolam, and five recommended using rectal diazepam. All 11 emergency department guidelines described three phases in therapy. Intravenous medication, by phase, was indicated as such: initial phase – ten/11 guidelines recommended lorazepam, and eight/11 recommended diazepam; second phase – most (ten/11) guidelines recommended phenytoin, but other options were phenobarbital (nine/11), valproic acid (six/11), and either fosphenytoin or levetiracetam (each four/11); third phase – four/11 guidelines included the choice of repeating second phase therapy, whereas the other guidelines recommended using a variety of intravenous anesthetic agents (thiopental, midazolam, propofol, and pentobarbital).

ConclusionsAll of the guidelines share a similar framework for management of status epilepticus. The choice in route of administration and drug type varied across guidelines. Hence, the adoption of a particular guideline should take account of local practice options in health service delivery.

Esta análise sistemática de diretrizes nacionais ou regionais publicadas em inglês tem como objetivo entender melhor a diferença no tratamento do estado de mal epiléptico pré-hospitalar e no departamento de emergência.

FontesPesquisa sistemática de diretrizes nacionais ou regionais (janeiro de 2000 a fevereiro de 2017) contidas nas base de dados do Pubmed e do Google Acadêmico e listas de referência de artigos. As palavras-chave da busca foram estado de mal epiléptico, convulsão prolongada, tratamento e diretriz.

Resumo do achados356 artigos foram identificados, e 13 foram selecionados de acordo com os critérios de inclusão. Em todas as seis diretrizes pré-hospitalares, o caminho preferencial de administração da medicação foi utilizar alternativas à via intravenosa: todas recomendaram midazolam bucal e intranasal; três também recomendaram midazolam intramuscular; e cinco recomendaram utilizar o diazepam via retal. Todas as 11 diretrizes de departamento de emergência descreveram três fases na terapia. No que diz respeito à medicação intravenosa, por fase, temos: fase inicial – 10/11 diretrizes recomendaram lorazepam e 8/11 recomendaram diazepam; segunda fase – a maioria (10/11) das diretrizes recomendou fenitoína, porém outras opções foram fenobarbital (9/11), ácido valpróico (6/11) e fosfenitoína ou levetiracetam (individualmente, 4/11); terceira fase – 4/11 diretrizes incluíram a opção de repetir a terapia da segunda fase, ao passo que as outras diretrizes recomendaram utilizar diversos agentes anestésicos intravenosos (tiopental, midazolam, propofol e pentobarbital).

ConclusõesTodas as diretrizes compartilham uma estrutura semelhante para manejo do estado de mal epiléptico. A escolha da via de administração e do tipo de medicamento variou em todas as diretrizes. Assim, a adoção de uma diretriz específica deve levar em consideração as opções da prática local na prestação de serviços de saúde.

Status epilepticus (SE) is defined as “a condition resulting either from the failure of mechanisms responsible for seizure termination or from the initiation of mechanisms which lead to abnormally prolonged seizures (after time point t1), and a condition that can have long-term consequences (after time point t2), including neuronal death, neuronal injury, and alteration of neuronal networks, depending on the type and duration of seizures, etc. In the case of convulsive (tonic–clonic) SE, both time points (t1 at 5min and t2 at 30min) are based on animal experiments and clinical research”.1

Therefore, in children, there are two subgroups of patients presenting with a seizure: those with brief episodes <5min duration (before t1) that are highly likely to resolve without treatment; and those with episodes >7min, who are more likely to progress to prolonged episodes necessitating acute treatment to stop the seizure. The consensus of the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) task force on the classification of SE is that treatment of convulsive seizures should therefore be initiated at around 5min.1

This article discusses some of the issues related to emergency anticonvulsant treatment of acute, prolonged seizures and SE in children with particular emphases on pre-hospital, emergency medical services (EMS), and emergency department (ED) guidelines, as well as protocols used by national and regional societies, organizations, and authorities. The reader interested in other management, investigations, and subsequent clinical follow-up in the outpatient department or by the primary care practitioner should review recent practice reviews and the American Academy of Neurology recommendations.2,3

MethodsSource of dataA systematic review of articles available in the PubMed and Google Scholar databases was carried out. Reference lists of articles identified were also checked. The search strategy included the combination of the following keywords in English: status epilepticus, prolonged seizure, treatment, and guideline.

Selection criteriaIn this qualitative review, articles were selected for consideration using the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) group 2009 statement.4 Published articles were included in the review when they met the following criteria: (1) protocol or guideline on the use of anticonvulsant drug treatment for prolonged seizure or SE published January 1st, 2000 to February 28th, 2017; (2) publication that featured a national or regional guideline for the pediatric population in the EMS or ED setting; and (3) when more than one article was identified from the same organization or society, the most recent publication was included.

All articles that met the inclusion criteria were submitted to data extraction and critical evaluation by each author. The main characteristics were summarized following data extraction: authorship; period of management; EMS or ED; time course of treatment; and recommended medication and administration route.

Data synthesis/analysisThe search strategy of the databases identified a total of 356 listed titles. Each abstract was screened and 344 were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Twelve articles were eligible for full review, and their reference lists identified one further article. A total of 13 articles were therefore included in the qualitative synthesis, and their findings were descriptively analyzed.5–17

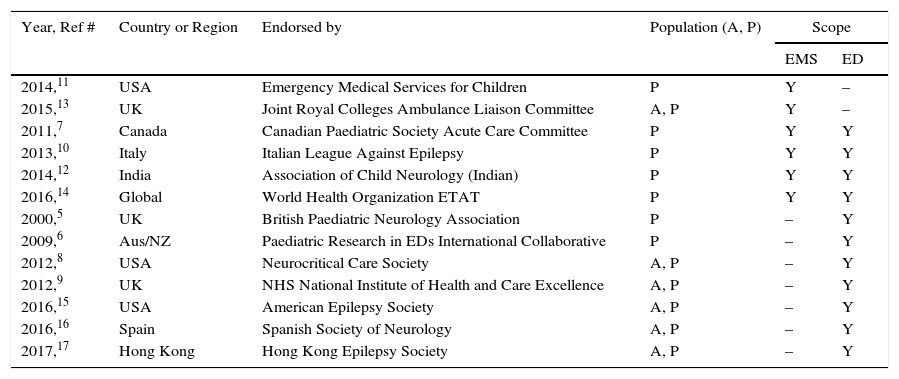

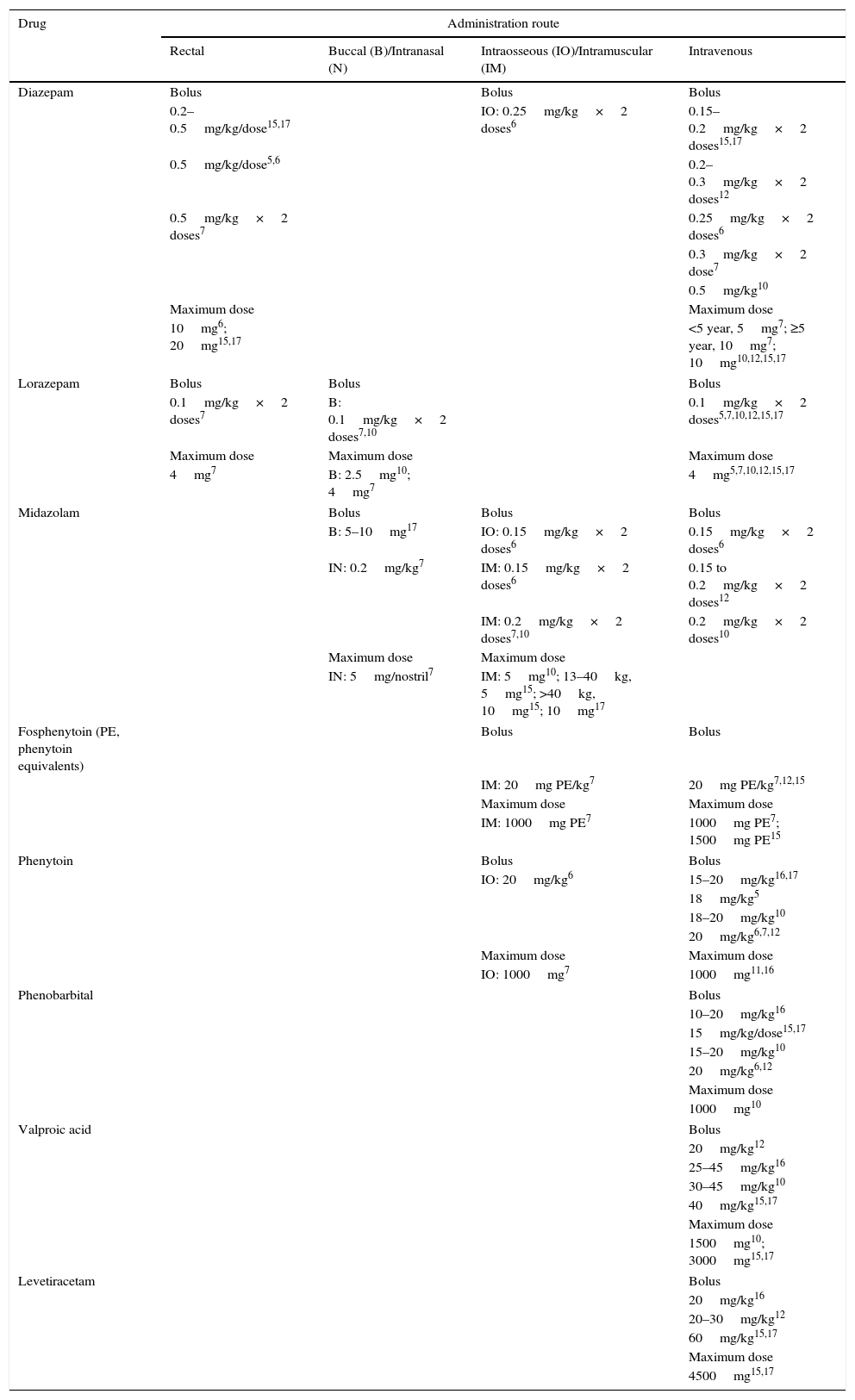

Results and discussionTable 1 describes the characteristics of the treatment guidelines. Table 2 presents use of immediate (“STAT” or statim [Latin]) anticonvulsant drug by type, dosing and route of administration covered in the guidelines. It is evident that the guidelines do not recommend exactly the same dosing for each anticonvulsant drug. However, these differences may be due to regional preference, history, or experience. Developers of new guidelines should take into account the spread in dosing and the maxima recommended, as well as any new clinical drug studies that are published after 2017.

Guideline or protocol characteristics.

| Year, Ref # | Country or Region | Endorsed by | Population (A, P) | Scope | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EMS | ED | ||||

| 2014,11 | USA | Emergency Medical Services for Children | P | Y | – |

| 2015,13 | UK | Joint Royal Colleges Ambulance Liaison Committee | A, P | Y | – |

| 2011,7 | Canada | Canadian Paediatric Society Acute Care Committee | P | Y | Y |

| 2013,10 | Italy | Italian League Against Epilepsy | P | Y | Y |

| 2014,12 | India | Association of Child Neurology (Indian) | P | Y | Y |

| 2016,14 | Global | World Health Organization ETAT | P | Y | Y |

| 2000,5 | UK | British Paediatric Neurology Association | P | – | Y |

| 2009,6 | Aus/NZ | Paediatric Research in EDs International Collaborative | P | – | Y |

| 2012,8 | USA | Neurocritical Care Society | A, P | – | Y |

| 2012,9 | UK | NHS National Institute of Health and Care Excellence | A, P | – | Y |

| 2016,15 | USA | American Epilepsy Society | A, P | – | Y |

| 2016,16 | Spain | Spanish Society of Neurology | A, P | – | Y |

| 2017,17 | Hong Kong | Hong Kong Epilepsy Society | A, P | – | Y |

A, adult; P, pediatric; Aus/NZ, Australia and New Zealand; ED, Emergency Department; EMS, Emergency Medical Services; ETAT, pediatric emergency triage assessment and treatment; NHS, National Health Service; UK, United Kingdom; USA, United States of America; Y, yes.

Commonly used immediate anticonvulsant drug, administration route and dose.

| Drug | Administration route | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rectal | Buccal (B)/Intranasal (N) | Intraosseous (IO)/Intramuscular (IM) | Intravenous | |

| Diazepam | Bolus | Bolus | Bolus | |

| 0.2–0.5mg/kg/dose15,17 | IO: 0.25mg/kg×2 doses6 | 0.15–0.2mg/kg×2 doses15,17 | ||

| 0.5mg/kg/dose5,6 | 0.2–0.3mg/kg×2 doses12 | |||

| 0.5mg/kg×2 doses7 | 0.25mg/kg×2 doses6 | |||

| 0.3mg/kg×2 dose7 | ||||

| 0.5mg/kg10 | ||||

| Maximum dose | Maximum dose | |||

| 10mg6; 20mg15,17 | <5 year, 5mg7; ≥5 year, 10mg7; 10mg10,12,15,17 | |||

| Lorazepam | Bolus | Bolus | Bolus | |

| 0.1mg/kg×2 doses7 | B: 0.1mg/kg×2 doses7,10 | 0.1mg/kg×2 doses5,7,10,12,15,17 | ||

| Maximum dose | Maximum dose | Maximum dose | ||

| 4mg7 | B: 2.5mg10; 4mg7 | 4mg5,7,10,12,15,17 | ||

| Midazolam | Bolus | Bolus | Bolus | |

| B: 5–10mg17 | IO: 0.15mg/kg×2 doses6 | 0.15mg/kg×2 doses6 | ||

| IN: 0.2mg/kg7 | IM: 0.15mg/kg×2 doses6 | 0.15 to 0.2mg/kg×2 doses12 | ||

| IM: 0.2mg/kg×2 doses7,10 | 0.2mg/kg×2 doses10 | |||

| Maximum dose | Maximum dose | |||

| IN: 5mg/nostril7 | IM: 5mg10; 13–40kg, 5mg15; >40kg, 10mg15; 10mg17 | |||

| Fosphenytoin (PE, phenytoin equivalents) | Bolus | Bolus | ||

| IM: 20mg PE/kg7 | 20mg PE/kg7,12,15 | |||

| Maximum dose | Maximum dose | |||

| IM: 1000mg PE7 | 1000mg PE7; 1500mg PE15 | |||

| Phenytoin | Bolus | Bolus | ||

| IO: 20mg/kg6 | 15–20mg/kg16,17 | |||

| 18mg/kg5 | ||||

| 18–20mg/kg10 | ||||

| 20mg/kg6,7,12 | ||||

| Maximum dose | Maximum dose | |||

| IO: 1000mg7 | 1000mg11,16 | |||

| Phenobarbital | Bolus | |||

| 10–20mg/kg16 | ||||

| 15mg/kg/dose15,17 | ||||

| 15–20mg/kg10 | ||||

| 20mg/kg6,12 | ||||

| Maximum dose | ||||

| 1000mg10 | ||||

| Valproic acid | Bolus | |||

| 20mg/kg12 | ||||

| 25–45mg/kg16 | ||||

| 30–45mg/kg10 | ||||

| 40mg/kg15,17 | ||||

| Maximum dose | ||||

| 1500mg10; 3000mg15,17 | ||||

| Levetiracetam | Bolus | |||

| 20mg/kg16 | ||||

| 20–30mg/kg12 | ||||

| 60mg/kg15,17 | ||||

| Maximum dose | ||||

| 4500mg15,17 | ||||

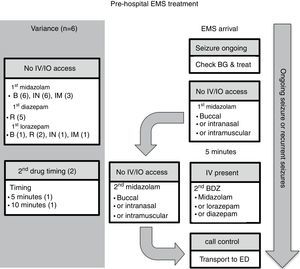

Six guidelines focused on EMS management.7,10–14Fig. 1 presents the algorithm by the Emergency Medical Services for Children (EMSC) for comparison.11 This guideline should be applied to children with a witnessed seizure that was not due to trauma, and was ongoing at the time of arrival of the EMS.

Pre-hospital EMS treatment. B, buccal; BDZ, benzodiazepine; BG, blood glucose; ED, emergency department; EMS, emergency medical system; IO, intraosseous; IN, intranasal; IM, intramuscular; IV, intravenous; R, rectal. Note: the number in parentheses is guidelines-out-of-six in this category (see text for details).

Overall, all six guidelines recommended buccal midazolam or intranasal midazolam, and three recommended intramuscular midazolam.10,11,14 Five guidelines recommended rectal diazepam as an option.7,10,12–14 A second dose of benzodiazepine was recommended in two of the guidelines, one at 5min11 and the other at 10min.13 All of the guidelines stated a preference for alternative non-intravenous routes of administration rather than gain intravenous access on arrival. Two of the guidelines11,13 recommended attempting to place either intravenous or intraosseous access in specific situations. Finally, only one of the guidelines provided criteria for patient transfer to ED.13

Comment on pre-hospital EMS guidelinesMidazolam through the buccal or intranasal route was recommended in the six pre-hospital guidelines. This guidance likely reflects the efficacy of midazolam versus diazepam, and the ease of administration by these access routes. However, rectal diazepam was still present in most of the pre-hospital guidelines. Buccal midazolam is more effective than rectal diazepam for stopping seizures and reducing their recurrence within 1h of onset, and as safe as rectal diazepam in relation to the incidence of respiratory depression.18 The effectiveness of intranasal midazolam is similar to, or more effective than rectal diazepam. Intranasal midazolam also has a shorter drug administration time and faster action to seizure cessation than rectal diazepam. Intranasal midazolam is easy to administer, but it has a short-lasting nasal irritant effect. A systematic review demonstrated that midazolam, by any route, is superior in seizure cessation than diazepam, by any route.19

Besides efficacy and ease of administration, the choice of non-intravenous benzodiazepines depends on local availability, expertise, and preference. For example, according to Osborne et al.,13 ambulances in the United Kingdom did not carry midazolam, and so EMS staff would administer the patient's own buccal or intranasal midazolam, if available; otherwise, rectal diazepam would be used because of the difficulty gaining intravenous access in children. For similar reasons, rectal diazepam was commonly available and recommended in the Italian League Against Epilepsy pre-hospital guideline.10 The World Health Organization (WHO) pediatric emergency triage assessment and treatment (ETAT) guideline14 recommends that, when oral and intranasal preparations of midazolam and lorazepam are not readily available, especially in resource-limited settings, the available intravenous preparations could be administered through the oral or intranasal routes. Last, intramuscular midazolam was recommended in three of the six guidelines.10,11,14 Such administration requires additional expertise, and it is effective and safe. For example, in the Rapid Anticonvulsant Medication Prior to Arrival Trial (RAMPART), intramuscular midazolam was as effective as intravenous lorazepam in the pre-hospital setting.20 Similar rates of endotracheal intubation and recurrence of seizures were observed in both the midazolam and lorazepam groups. Considered together, all of the guidelines recommended the non-intravenous route of administration.

Two of the guidelines recommend attempting intravenous or intraosseous access only in specific situations.11,13 The EMSC algorithm11 in the United States considers obtaining intravenous or intraosseous access when the expected transport time was long, or when it would be required for other aspects of patient care such as intravenous fluid or other medications. The United Kingdom Joint Royal Colleges Ambulance Liaison Committee (JRCALC) algorithm13 recommends a second dose of diazepam if the seizure continues after rectal diazepam, and that must be given via the intravenous or intraosseous route. Establishing intravenous access could be difficult, however, in a child with an ongoing seizure in the pre-hospital setting. It requires trained EMS providers and equipment, which may be lacking in resource-limited settings (see ETAT guideline14). Furthermore, the seizure may stop before intravenous access is obtained, making the procedure unnecessary11; the time needed to set-up intravenous access may prolong the time at the scene and delay drug administration.13

Two of the guidelines recommended administering a second dose of benzodiazepines in the pre-hospital setting.11,13 The other four guidelines did not include this option. Maintaining adequate airway, breathing, and circulation while the patient is transferred to the ED,7,10,12,13 as well as communicating with the medical control center for advice, are recommended.11 One guideline provided guidance on criteria for transfer to hospital. The JRCALC guideline13 recommends transfer to hospital for children under 1 year of age, cases with their first seizure or first febrile convulsion, and cases with serial seizures or difficulty monitoring. The JRCALC guideline13 also recommends a time-critical transfer to the hospital if any of the following are present: difficulty with airway, breathing, circulation, or disability problems; serious head injury; SE after failed treatment; or, underlying infection.

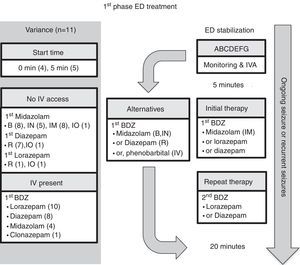

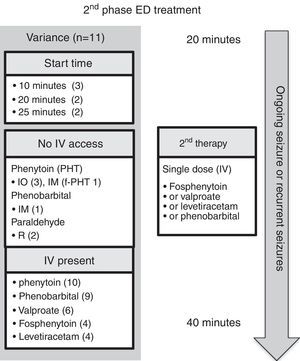

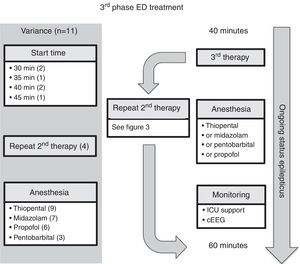

Emergency department managementEleven guidelines focused on ED management.5–10,12,14–17 For comparison, the authors have selected the American Epilepsy Society (AES) algorithm for convulsive seizure lasting at least 5min.15 The structure of this algorithm follows three phases of therapy (Figs. 2–4, and Table 3). The first phase of therapy is initial stabilization and the administration of a benzodiazepine. The second phase of therapy is the administration of a non-benzodiazepine second anticonvulsant drug, when benzodiazepines have failed. The third phase of therapy is the administration of a general anesthetic drug under intensive care support when SE has become refractory to at least two anticonvulsant drugs from the first and second therapy phases.

First-phase ED treatment. ABCDEFG, stabilization support with intervention for Airway, Breathing, Circulation, Dextrose, Essential neurology, Fluids, Global picture; BDZ, benzodiazepine; ED, emergency department; EMS, emergency medical system; IO, intraosseous; IN, intranasal; IM, intramuscular; IV, intravenous; IVA, intravenous access; R, rectal. Note: the number in parentheses is guidelines-out-of-11 in this category (see text for details).

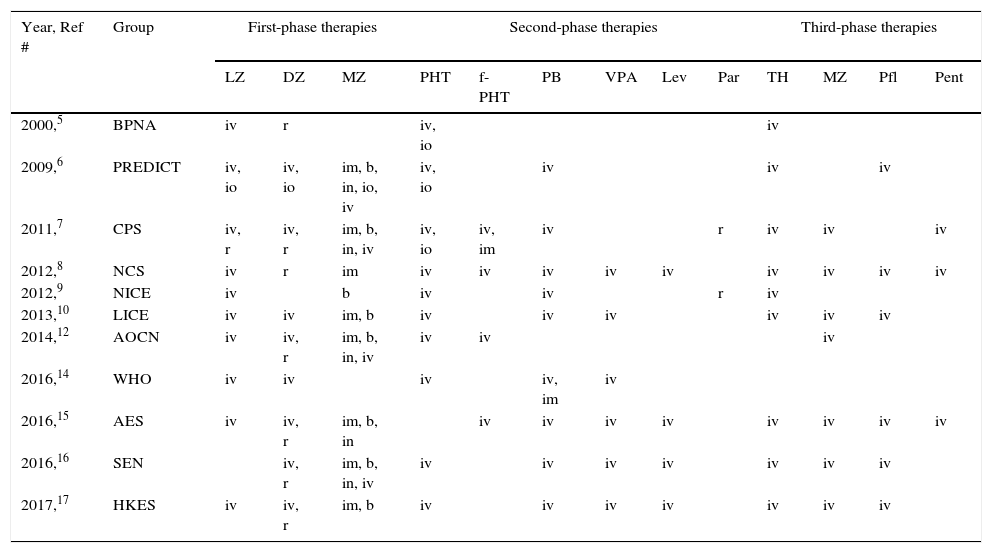

Comparison of anticonvulsant drugs used in each of the three phases of therapy and their administration routes (see also, Tables 1 and 2).

| Year, Ref # | Group | First-phase therapies | Second-phase therapies | Third-phase therapies | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LZ | DZ | MZ | PHT | f-PHT | PB | VPA | Lev | Par | TH | MZ | Pfl | Pent | ||

| 2000,5 | BPNA | iv | r | iv, io | iv | |||||||||

| 2009,6 | PREDICT | iv, io | iv, io | im, b, in, io, iv | iv, io | iv | iv | iv | ||||||

| 2011,7 | CPS | iv, r | iv, r | im, b, in, iv | iv, io | iv, im | iv | r | iv | iv | iv | |||

| 2012,8 | NCS | iv | r | im | iv | iv | iv | iv | iv | iv | iv | iv | iv | |

| 2012,9 | NICE | iv | b | iv | iv | r | iv | |||||||

| 2013,10 | LICE | iv | iv | im, b | iv | iv | iv | iv | iv | iv | ||||

| 2014,12 | AOCN | iv | iv, r | im, b, in, iv | iv | iv | iv | |||||||

| 2016,14 | WHO | iv | iv | iv | iv, im | iv | ||||||||

| 2016,15 | AES | iv | iv, r | im, b, in | iv | iv | iv | iv | iv | iv | iv | iv | ||

| 2016,16 | SEN | iv, r | im, b, in, iv | iv | iv | iv | iv | iv | iv | iv | ||||

| 2017,17 | HKES | iv | iv, r | im, b | iv | iv | iv | iv | iv | iv | iv | |||

Groups: AES, American Epilepsy Society; AOCN, Association of Child Neurology (India); BPNA, British Paediatric Neurology Association; CPS, Canadian Paediatric Society; HKES, Hong Kong Epilepsy Society; LICE, Italian League Against Epilepsy; NCS, Neurocritical Care Society; NICE, National Health Service National Institute of Health and Care Excellence; PREDICT, Paediatric Research in Emergency Departments International Collaborative; SEN, Spanish Society of Neurology; WHO, World Health Organization. Therapies: DZ, diazepam; Lev, levetiracetam; LZ, lorazepam; MZ, midazolam; Par, paraldehyde; Pent, pentobarbital; PB, phenobarbital; f-PHT, fosphenytoin; PHT, phenytoin; Pfl, propofol; TH, thiopental; VPA, valproic acid. Routes: b, buccal; im, intramuscular; in, intranasal; io, intraosseous; iv, intravenous; r, rectal.

The time to starting each phase of therapy was similar across the guidelines. In the initial phase of therapy, nine of the guidelines reported a start time equal to, or earlier than the AES algorithm.5–7,9,10,12,15–17 The onset of the second and third phases of therapy were equal to, or earlier than, the AES start times in five of the guidelines that stated the start time.5–7,12,15 Endotracheal intubation was considered in the stabilization phase in two of the guidelines,8,15 and in the context of rapid sequence intubation in four of the guidelines.5–7,9

In regard to the route of anticonvulsant drug administration, intravenous access may be available after the pre-hospital stage of therapy (Fig. 1). When there is no intravenous access at the start of the ED stage of treatment, the guidelines recommend intraosseous access in the initial (n=1)6 or second phase of treatment (n=2).5,7 In both of these phases, benzodiazepines and phenytoin could be administered through the intraosseous route.

Comment on ED time courseNo significant discrepancies were observed among the guidelines in regard to the timing for starting each phase of anticonvulsant drug therapy. All guidelines recommended “starting the clock” when a seizure lasts longer than 5min, which can be assumed to be whenever an actively seizing patient arrives in the ED. This time point is also consistent with the new ILAE definition and classification of SE.1 A minor difference in timing in the guidelines is observed in the period needed for a stabilization phase, and the different intervals between administering the options in anticonvulsant drugs.

ED first phase anticonvulsant therapyIn regard to the choice of anticonvulsant drug treatment, a benzodiazepine was universally recommended in the initial phase of therapy (Fig. 2 and Table 3). Intravenous lorazepam was recommended in ten of the guidelines,5–10,12,14,15,17 followed by intravenous diazepam in eight of the guidelines.6,7,10,12,14–17 If no intravenous access was available, the most commonly recommended anticonvulsant drug was midazolam: intramuscular midazolam (n=8),6–8,10,12,15–17 buccal midazolam (n=8),6,7,9,10,12,15–17 or intranasal midazolam (n=5).6,7,12,15,16 As an alternative, rectal diazepam (n=7) was commonly recommended.5,7,8,12,15–17 A repeated dose of benzodiazepine was recommended in five guidelines; four of them considered the pre-hospital dose received,6,7,9,10 while the other excluded the pre-hospital dose.5 Intravenous phenobarbital was recommended as a non-benzodiazepine alternative in two of the guidelines.8,15

Comment on ED first phase anticonvulsant therapyIntravenous lorazepam and diazepam were the most commonly recommended intravenous benzodiazepines in the first phase of therapy. All except for one guideline (from the Spanish Society of Neurology) recommended intravenous lorazepam.16 In Spain, in 2016, intravenous lorazepam was not available; thus, intravenous clonazepam is recommended instead. Intravenous lorazepam or diazepam are efficacious and safe to use. For example, in one randomized controlled trial21 comparing intravenous lorazepam and intravenous diazepam, 72.9% of the lorazepam group and 72.1% of the diazepam group had cessation of SE within 10min without recurrence within 30min, with similar rates of assisted ventilation (17.6% in the lorazepam group and 16.0% in the diazepam group). In the resource-limited setting, one additional consideration with lorazepam use is the need for refrigeration of the drug, because of its degradation at high temperature. Although both intravenous lorazepam and diazepam are included in the WHO model list of essential medicines for children, the ETAT guideline recommends intravenous diazepam in high temperature regions with no refrigeration facility.14

When a repeat dose of benzodiazepine is required because of an ongoing seizure, four of the 11 guidelines6,7,9,10 recommended taking account of whether any pre-hospital benzodiazepine dose(s) had been administered, since EMS dosing would affect the choice of next anticonvulsant drug. Interestingly, these four guidelines were published after 2008, which is when Chin et al.22 showed that in community-onset childhood convulsive SE there was an association between no pre-hospital anticonvulsant drug treatment, or use of more than two doses of benzodiazepines, and SE lasting more than 60min. Moreover, their study demonstrated that treatment with more than two doses of benzodiazepines was associated with respiratory depression. Only one guideline, from 2000, recommended excluding consideration of prior EMS treatment,5 and that was on the basis of possible variability in pre-hospital dosing.

ED second phase anticonvulsant therapyIn the second phase of therapy (Fig. 3 and Table 3), guideline recommendations for intravenous medications included: phenytoin (n=10),5–10,12,14,16,17 phenobarbital (n=9),6–10,14–17 valproic acid (n=6),8,10,14–17 fosphenytoin (n=4),7,12,14,15 and levetiracetam (n=4).8,15–17 If no intravenous access was available, intraosseous phenytoin was recommended in three guidelines,5–7 and the other options presented were intramuscular fosphenytoin,7 phenobarbital,14 and rectal paraldehyde.5,7

Comment on ED second phase anticonvulsant therapyIntravenous phenytoin was the most commonly recommended therapy for benzodiazepine-refractory SE. Together with intravenous fosphenytoin (the prodrug of phenytoin), they were the second phase therapy of choice in all guidelines. There are a number of reasons why fosphenytoin should be recommended in preference to phenytoin: it does not require the excipient propylene glycol; it has less risk of hypotension and cardiac dysrhythmia; it does not cause the serious extravasation reaction, purple glove syndrome; and, it can be administered via the intramuscular route when intravenous access is not available.7

Intravenous phenobarbital was recommended in nine of the 11 guidelines.6–10,14–17 Of note, two guidelines recommended phenobarbital only if the patient had received phenytoin,9,16 the reasoning being that phenobarbital has more depressant side effects than phenytoin (e.g., respiratory depression and sedation), especially when benzodiazepines have already been used. The evidence for using intramuscular phenobarbital is based on pediatric practice in cerebral malaria.23 For example, an intramuscular dose of 20mg/kg reduces seizure frequency, but it causes an increased risk of respiratory depression and mortality, especially in those who have already received multiple doses of diazepam.23

Valproic acid was recommended in six of the 11 guidelines.8,10,14–17 Valproic acid may be hepatotoxic and may lead to hyperammonemia. Three of the guidelines point out that it should be avoided or used with caution in liver disease (or suspected metabolic disease) and in children younger than 2–3 years with uncertain seizure etiology.10,12,14 Valproic acid causes less hypotension or respiratory depression when compared with phenytoin or phenobarbital. For example, in a randomized controlled trial, although rapid intravenous loading of valproic acid stopped seizures in a comparable rate to intravenous phenobarbital (90% versus 77%, no statistical difference), the rate of adverse effects were lower (24% versus 74%); the phenobarbital group experienced more lethargy, vomiting, or respiratory depression.24 In comparison with intravenous phenytoin, valproic acid is as effective in seizure control, and better tolerated in regard to risk of hypotension and respiratory depression, but it does cause mild elevation of liver enzymes.25 Taken together, valproic acid can be considered an effective option for second phase anticonvulsant drug therapy.

Levetiracetam was recommended in four of the 11 guidelines.8,15–17 It has the advantages of good tolerability, intravenous administration over relatively short time, and absence of hemodynamic and sedative effects.10 Nonetheless, no randomized controlled trials of levetiracetam in pediatric convulsive SE have been conducted. A randomized, pilot open study has demonstrated equivalence of effectiveness in seizure control with lorazepam, and it has less associated respiratory depression and hypotension.26

Lastly, of relevance to the future of second phase anticonvulsant drug treatment, there is an on-going multicenter randomized comparative effectiveness study, the Established Status Epilepticus Treatment Trial (ESETT; ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT01960075; due to be completed on December 2019), which aims to determine the most effective ED treatment out of fosphenytoin, levetiracetam, and valproic acid for benzodiazepine-refractory SE, and provide information on effectiveness and safety in children.

ED third phase anticonvulsant therapyIn the third phase of therapy (Fig. 4 and Table 3), four guidelines included the choice for repeating second phase therapy.7,10,12,15 Nine guidelines recommended inducing anesthesia with thiopental5–9,12,15–17; all four of the guidelines which recommended rapid sequence intubation suggested thiopental as the inducting agent.5–7,9 Seven of the guidelines recommended using midazolam infusion,7,8,10,12,15–17 six recommended propofol infusion,6,8,10,15–17 and three recommended pentobarbital infusion.7,8,15

Comment on ED third phase anticonvulsant therapyAt the time of starting the third phase of anticonvulsant drug treatment, four of the 11 guidelines included the choice for repeating second phase therapy.7,10,12,15 The Canadian Pediatric Society Acute Care Committee guideline7 recommended a combination of using two second-phase drug therapies, each separated by a 5-minute interval, before proceeding to the induction of anesthesia. The Association of Child Neurology (India, 2013)12 guideline group considered the scenario when no intensive care bed is available, and recommended the following before a midazolam infusion: either valproic acid and phenobarbital, or levetiracetam. The Italian League Against Epilepsy guideline10 recommended valproic acid after second phase therapy, if delay or difficulty in endotracheal intubation was expected.

Finally, in regard to the choice of anesthetic agent, the guidelines do not have clear recommendations for preference between thiopental, midazolam, propofol, and pentobarbital. Rather, specific drug selection is deferred to local expertise. It should be noted, however, that although propofol is used in adult practice of refractory SE, the risk of propofol infusion syndrome in children is unacceptable and, therefore, continuous infusion is not recommended in a number of countries. In regard to the other anesthetic agents, the data on intensive care treatment of pediatric refractory SE are of poor quality, yet they show a hierarchy in strategies: early midazolam by continuous infusion, then barbiturates, and then trial of other anesthetic therapies.27,28 Recently, a two-year prospective observational study assessed the use of continuous infusion of anesthetic agent in pediatric patients (age range, 1 month to 21 years) with refractory SE not responding to two anticonvulsant drug classes.29 The United States Pediatric SE Research Group found that, in their 11 centers, midazolam and pentobarbital remain the mainstay of continuous infusion therapy.

ConclusionManaging a child who presents in an emergency with a seizure is a challenge; knowing how to best deal with acute interventions and follow-up is an important part of pediatric practice.30 Guidelines on anticonvulsant drug therapy for a seizure or SE before and after arrival in the ED serve as important reference documents in acute care. In this qualitative systematic review of 13 regional/national guidelines, we have found that each share similar frameworks for practice and time points. Different routes of benzodiazepine administration are feasible in the pre-hospital (EMS) and first phase of ED therapy. The choice of benzodiazepines depends on presence of intravenous access, local availability, skills of healthcare providers, and the resource setting. Valproic acid and levetiractam have better side effect profiles than phenytoin or fosphenytoin. Direct comparison of effectiveness and safety of different second phase therapy for SE awaits further clinical study. Finally, regarding the use of anesthetic agents in children, most of the experience and literature is in using midazolam and then pentobarbital by continuous infusion.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Au CC, Branco RG, Tasker RC. Management protocols for status epilepticus in the pediatric emergency room: systematic review article. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2017;93:84–94.