The Pediatric Assessment Triangle is a rapid assessment tool that uses only visual and auditory clues, requires no equipment, and takes 30–60s to perform. It's being used internationally in different emergency settings, but few studies have assessed its performance. The aim of this narrative biomedical review is to summarize the literature available regarding the usefulness of the Pediatric Assessment Triangle in clinical practice.

SourcesThe authors carried out a non-systematic review in the PubMed®, MEDLINE®, and EMBASE® databases, searching for articles published between 1999–2016 using the keywords “pediatric assessment triangle,” “pediatric triage,” “pediatric assessment tools,” and “pediatric emergency department.”

Summary of the findingsThe Pediatric Assessment Triangle has demonstrated itself to be useful to assess sick children in the prehospital setting and make transport decisions. It has been incorporated, as an essential instrument for assessing sick children, into different life support courses, although little has been written about the effectiveness of teaching it. Little has been published about the performance of this tool in the initial evaluation in the emergency department. In the emergency department, the Pediatric Assessment Triangle is useful to identify the children at triage who require more urgent care. Recent studies have assessed and proved its efficacy to also identify those patients having more serious health conditions who are eventually admitted to the hospital.

ConclusionsThe Pediatric Assessment Triangle is quickly spreading internationally and its clinical applicability is very promising. Nevertheless, it is imperative to promote research for clinical validation, especially for clinical use by emergency pediatricians and physicians.

O Triângulo de Avaliação Pediátrica é uma ferramenta de avaliação rápida que utiliza apenas pistas visuais e auditivas, não necessita de equipamentos e leva de 30-60 segundos para realização. Ele tem sido utilizado internacionalmente em diferentes configurações de emergência, porém poucos estudos avaliaram seu desempenho. O objetivo dessa análise biomédica narrativa é resumir a literatura disponível com relação à utilidade do Triângulo de Avaliação Pediátrica na prática clínica.

FontesRealizamos uma análise não sistemática nas bases de dados do PubMed®, MEDLINE® e EMBASE® buscando artigos publicados entre 1999-2016 utilizando as palavras-chave “triângulo de avaliação pediátrica”, “triângulo pediátrico”, “ferramentas de avaliação pediátrica” e “departamento de emergência pediátrica”.

Resumo dos achadosO Triângulo de Avaliação Pediátrica demonstrou ser útil na avaliação de crianças doentes na configuração pré-hospitalar e na tomada de decisões de transporte. Ele foi incorporado, como um instrumento essencial na avaliação de crianças doentes, em diferentes cursos de suporte de vida, apesar de pouco ter sido escrito sobre a eficácia de ensino do Triângulo de Avaliação Pediátrica. Pouco foi publicado sobre o desempenho do Triângulo de Avaliação Pediátrica na avaliação inicial no departamento de emergência (DE). No DE, o Triângulo de Avaliação Pediátrica é útil para identificar, na triagem, crianças que exigem cuidado mais urgente. Estudos recentes avaliaram e provaram a eficácia do Triângulo de Avaliação Pediátrica também na identificação dos pacientes com doenças de saúde mais graves e, eventualmente, são internados no hospital.

ConclusõesO Triângulo de Avaliação Pediátrica está se difundindo rapidamente de forma internacional e sua aplicabilidade clínica é muito promissora. Contudo, é essencial promover pesquisa para validação clínica, principalmente para o uso clínico por pediatras e médicos de emergência.

Is this child sick? Should I begin any emergency intervention? Any provider should be able to answer quickly these questions whenever the provider comes in front of a child seeking for urgent medical attention (in the prehospital setting or emergency department [ED]).

Every day, thousands of children are brought to different emergency settings worldwide. Children account for about one-fourth of the visits to hospital EDs in the United States, and around 30 million children are assessed by general practitioners or pediatricians annually.1 Infants younger than 12 months are the age group with the highest per capita rate of visits to the ED (91.3 per 100 infants in 2005). In the prehospital setting, 10% to 13% of ambulance transports are for children.2 In Europe, in the UK, 25–30% of all Accident and Emergency attendances are children.3

In pediatric emergency medicine, stabilizing the patient must be performed before establishing a diagnosis; a problem solving approach is required. It is, therefore, essential to have a tool that allows a rapid initial assessment and identifies the problem that must be solved. Unfortunately, initial assessment of a critically ill or injured child is often difficult, even for the experienced clinician. Physical examination and vital signs assessment, the cornerstone of the adult assessment, may be compromised with a hands-on evaluation. Initial assessment of the child presenting to emergency should ideally be via an “across the room” assessment.4

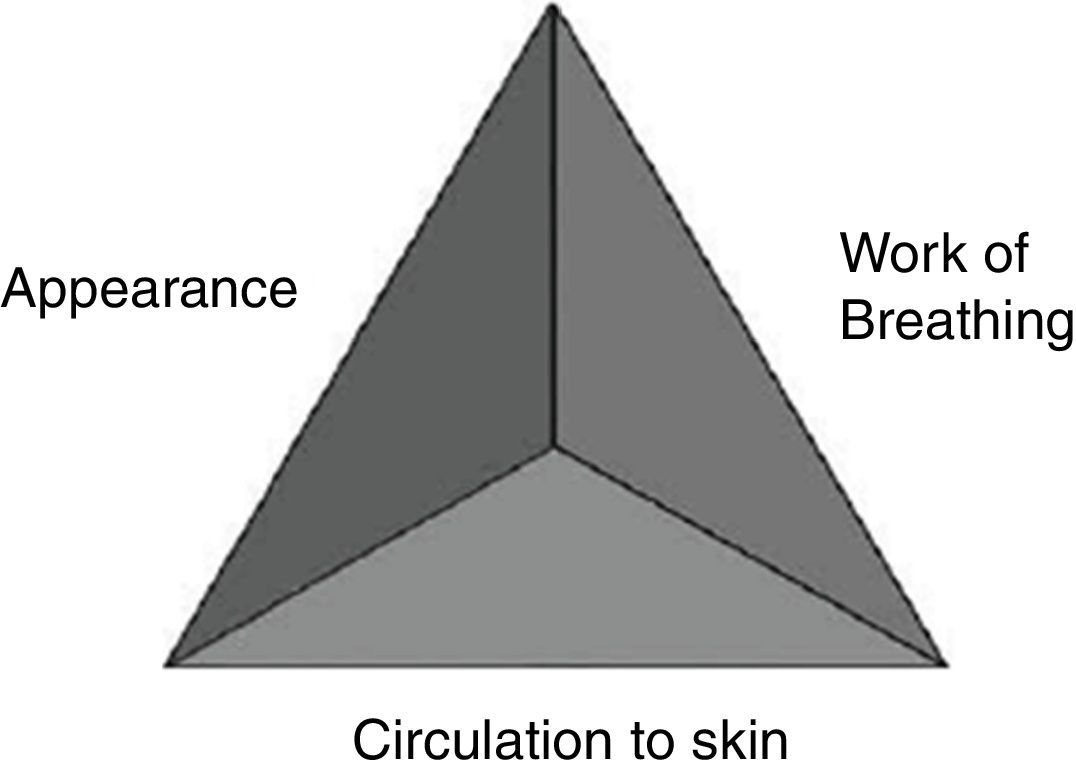

The Pediatric Assessment Triangle: definitionIn 2000, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) published the first national pediatric educational program for prehospital providers, which introduced a new rapid assessment tool, called the Pediatric Assessment Triangle (PAT). The PAT is not a diagnostic tool, it was designed to enable the provider to articulate formally a general impression of the child, establish the severity of the presentation and category of pathophysiology, and determine the type and urgency of intervention.5 The PAT somehow summarizes “gut feeling” findings, and promotes consistent communication among medical professionals about the child's physiological status.

Intended for use in rapid assessment, the PAT uses only visual and auditory clues, requires no equipment, and takes 30–60s to perform. The three components of the PAT are appearance, work of breathing, and circulation to the skin (Fig. 1). Each component of the PAT is evaluated separately, using specific predefined physical, visual, or auditory findings. If the clinician detects an abnormal finding, the corresponding component is, by definition, abnormal. Together, the three components of the PAT reflect the child's overall physiologic status, or the child's general state of oxygenation, ventilation, perfusion, and brain function.2

Appearance is the most important component when determining how severe the illness or injury is, the need for treatment, and the response to therapy. It reflects the adequacy of ventilation, oxygenation, brain perfusion, body homeostasis, and central nervous system function. This arm of the PAT is delineated by the “TICLS” mnemonic: Tone, Interactiveness, Consolability, Look or Gaze, and Speech or Cry. Important clues such as the infant's tone, consolability, interaction with caregivers and others, and strength of cry can inform the provider of the child's appearance as normal or abnormal (for age and development). The interaction with the environment and expected normal behavior varies according to the age of the patient. Knowledge of normal development in childhood is essential for the assessment of the appearance.

The other elements of the PAT provide more specific information about the type of physiologic derangement.

Work of breathing describes the child's respiratory status, especially the degree to which the child must work in order to oxygenate and ventilate. Assessing work of breathing requires listening carefully for audible abnormal airway sounds (e.g., stridor, grunting, and wheezing), and looking for signs of increased breathing effort (abnormal positioning, retractions, or flaring of the nostrils on inspiration). The type of abnormal airway noise provides information about the location of the disease, while the number and location of retractions and the position of the patient report the intensity of respiratory work.

Circulation to the skin reflects the general perfusion of blood throughout the body. The provider notes the color and color pattern of the skin and mucous membranes. In the context of blood loss/fluid loss or changes in venous tone, compensatory mechanisms shunt blood to vital organs such as the heart and brain, and away from the skin and the periphery of the body. By noting changes in skin color and skin perfusion (such as pallor, cyanosis, or mottling), the provider may recognize early signs of shock.

An abnormality noted in any of the arms of the PAT denotes an unstable child; i.e., a child who will require some immediate clinical intervention. The pattern of affected arms within the PAT further categorizes the child into 1 of 5 categories: respiratory distress, respiratory failure, shock, central nervous system or metabolic disorder, and cardiopulmonary failure. The specific category then dictates the type and urgency of intervention.2,6

In 2005, an Emergency Medical Services for Children (EMSC) task force was convened to review definitions and assessment approaches for national-level pediatric life support programs and courses. Representatives from the AAP, the American College of Emergency Physicians, the American Heart Association Emergency Nurses Association, the National Association of EMTs, the Children's National Medical Center, and the New York Center for Pediatric Emergency Medicine met to adopt consensus definitions and approaches to pediatric emergency care. The group concluded that a standard algorithm for pediatric emergency assessment should start with the PAT.5

Since its creation as a rapid assessment tool, the PAT has been taught to and used internationally by health professionals in various different settings, although there have been very few validation studies.

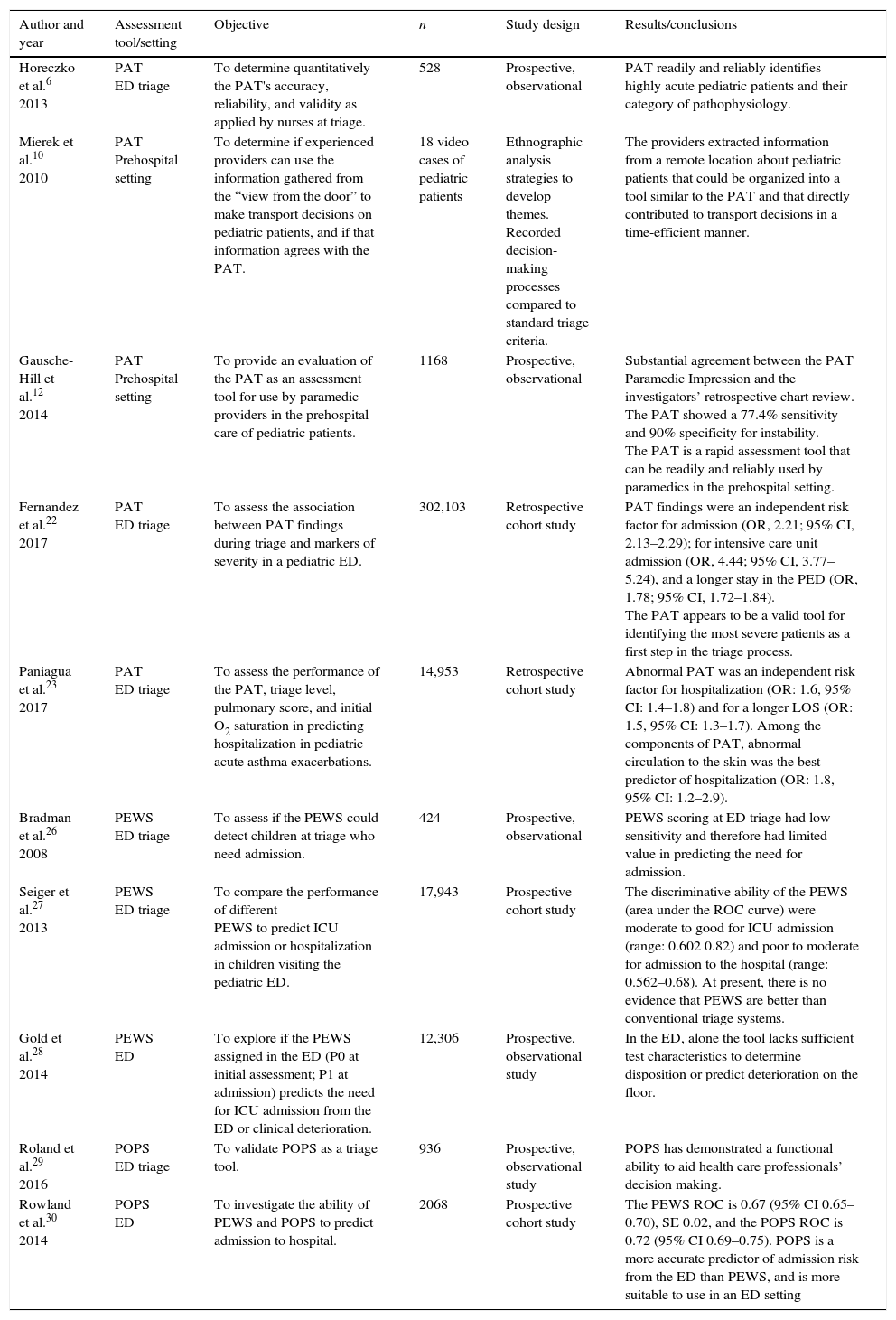

This non-systematic review aims to update the professionals involved in the care of children in EDs in relation to the literature available regarding the clinical use of the PAT. It was carried out using the keywords “pediatric assessment triangle,” “pediatric triage,” “pediatric assessment tools,” and “pediatric emergency department” in the PubMed®, MEDLINE®, and EMBASE® databases, searching for articles published between 1999–2016 (Table 1).

Pediatric assessment tools.

| Author and year | Assessment tool/setting | Objective | n | Study design | Results/conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Horeczko et al.6 2013 | PAT ED triage | To determine quantitatively the PAT's accuracy, reliability, and validity as applied by nurses at triage. | 528 | Prospective, observational | PAT readily and reliably identifies highly acute pediatric patients and their category of pathophysiology. |

| Mierek et al.10 2010 | PAT Prehospital setting | To determine if experienced providers can use the information gathered from the “view from the door” to make transport decisions on pediatric patients, and if that information agrees with the PAT. | 18 video cases of pediatric patients | Ethnographic analysis strategies to develop themes. Recorded decision-making processes compared to standard triage criteria. | The providers extracted information from a remote location about pediatric patients that could be organized into a tool similar to the PAT and that directly contributed to transport decisions in a time-efficient manner. |

| Gausche-Hill et al.12 2014 | PAT Prehospital setting | To provide an evaluation of the PAT as an assessment tool for use by paramedic providers in the prehospital care of pediatric patients. | 1168 | Prospective, observational | Substantial agreement between the PAT Paramedic Impression and the investigators’ retrospective chart review. The PAT showed a 77.4% sensitivity and 90% specificity for instability. The PAT is a rapid assessment tool that can be readily and reliably used by paramedics in the prehospital setting. |

| Fernandez et al.22 2017 | PAT ED triage | To assess the association between PAT findings during triage and markers of severity in a pediatric ED. | 302,103 | Retrospective cohort study | PAT findings were an independent risk factor for admission (OR, 2.21; 95% CI, 2.13–2.29); for intensive care unit admission (OR, 4.44; 95% CI, 3.77–5.24), and a longer stay in the PED (OR, 1.78; 95% CI, 1.72–1.84). The PAT appears to be a valid tool for identifying the most severe patients as a first step in the triage process. |

| Paniagua et al.23 2017 | PAT ED triage | To assess the performance of the PAT, triage level, pulmonary score, and initial O2 saturation in predicting hospitalization in pediatric acute asthma exacerbations. | 14,953 | Retrospective cohort study | Abnormal PAT was an independent risk factor for hospitalization (OR: 1.6, 95% CI: 1.4–1.8) and for a longer LOS (OR: 1.5, 95% CI: 1.3–1.7). Among the components of PAT, abnormal circulation to the skin was the best predictor of hospitalization (OR: 1.8, 95% CI: 1.2–2.9). |

| Bradman et al.26 2008 | PEWS ED triage | To assess if the PEWS could detect children at triage who need admission. | 424 | Prospective, observational | PEWS scoring at ED triage had low sensitivity and therefore had limited value in predicting the need for admission. |

| Seiger et al.27 2013 | PEWS ED triage | To compare the performance of different PEWS to predict ICU admission or hospitalization in children visiting the pediatric ED. | 17,943 | Prospective cohort study | The discriminative ability of the PEWS (area under the ROC curve) were moderate to good for ICU admission (range: 0.602 0.82) and poor to moderate for admission to the hospital (range: 0.562–0.68). At present, there is no evidence that PEWS are better than conventional triage systems. |

| Gold et al.28 2014 | PEWS ED | To explore if the PEWS assigned in the ED (P0 at initial assessment; P1 at admission) predicts the need for ICU admission from the ED or clinical deterioration. | 12,306 | Prospective, observational study | In the ED, alone the tool lacks sufficient test characteristics to determine disposition or predict deterioration on the floor. |

| Roland et al.29 2016 | POPS ED triage | To validate POPS as a triage tool. | 936 | Prospective, observational study | POPS has demonstrated a functional ability to aid health care professionals’ decision making. |

| Rowland et al.30 2014 | POPS ED | To investigate the ability of PEWS and POPS to predict admission to hospital. | 2068 | Prospective cohort study | The PEWS ROC is 0.67 (95% CI 0.65–0.70), SE 0.02, and the POPS ROC is 0.72 (95% CI 0.69–0.75). POPS is a more accurate predictor of admission risk from the ED than PEWS, and is more suitable to use in an ED setting |

PAT, Pediatric Assessment Triangle; PEWS, Pediatric Early Warning Score; POPS, Pediatric Observation Priority Score; ED, emergency department.

The tool has been incorporated, as an essential instrument for assessing sick children, into different life support courses, including the Advanced Pediatric Life Support (APLS), Emergency Nursing Pediatric Course, Pediatric Advanced Life Support (PALS), Pediatric Education for Prehospital Professionals (PEPP), Special Children's Outreach and Prehospital Education, and Teaching Resource for Instructors in Prehospital Pediatrics.5

The APLS course aims to improve the early management of acutely ill and injured children through training and education of health care professionals. It is a valuable resource for pediatric residents and it is part of the program of continuing education of pediatricians and emergency physicians in the United States.7

The first APLS course was implemented in 1984 in the United States. The first edition of the APLS course student manual was published by the AAP and ACEP in 1989. All editions were guided by the APLS Joint Task Force, and all were built on the foundation laid by Dr. Brushore-Fallis and her colleagues.8

Nowadays, APLS course directors can be found in more than 15 countries worldwide. Despite its widespread dissemination, little has been written about the effectiveness of teaching the PAT. It was possible to retrieve only one article, published by Benito et al., where the official directors of APLS courses in Spain were asked for specific information regarding the courses given to date. The authors focused on the results of the course evaluation survey conducted among students at the end of the course. The Spanish Society of Pediatric Emergency Medicine (SEUP) introduced the APLS course in Spain in 2005. The first official instructor course was offered in Bilbao, Spain. Since then, SEUP members have offered 44 courses in different regions of Spain, in which 1520 students have participated. Currently, the APLS course is taught at six specific sites located in different regions of Spain, and there are 11 official APLS course directors and more than 90 instructors. In the satisfaction surveys analyzed by Benito et al., 94.8% of the APLS students agreed that the course was very useful for daily clinical practice. In addition, more than 80% of respondents indicated that they always use the PAT approach in their clinical practice. Almost all respondents believed that the APLS course should be included in the pediatric residency-training program and that it should be a requirement.9

PAT in the prehospital settingThe PAT was initially designed to be used in the prehospital setting. Thus, first attempts to validate the tool were carried out in this setting. In 2010, Mierek et al. published a study in which 12 EMS providers were recruited to observe two videos of pediatric patients and make a transport decision based on their observations. After each case, the participants were interviewed to determine why they made their decision. Interviews were then transcribed and analyzed separately by three researchers. They concluded that providers could extract information from a remote location about pediatric patients that could be organized into a tool similar to the PAT. This remotely-obtained information directly contributed to transport decisions and supported that the tool was a time-efficient method of triaging patients. They stated that the PAT could be taught with more confidence and greater emphasis, and ultimately, applied more broadly to prehospital medicine.10

In 2011, Horeczko et al. published an article presenting the PAT to prehospital providers as a tool for the recognition and treatment of the acutely ill or injured child.11

The first study to evaluate the performance of the PAT by paramedics in the prehospital setting was published by the same group in 2014. In that study, a group of paramedics from Los Angeles Fire Department selected a convenience sample of assessments of the pediatric patients transported to 29 participating institutions, during 18 months, after been trained in the Pediatric Education for Prehospital Professionals course, PAT study procedures, and in applying the PAT to assess children 0–14 years of age. Two investigators then, blinded to the paramedic PAT assessment, reviewed the ED medical records and entered the data into the secure web-based database. “PAT Investigator Impression” served as the criterion standard for the PAT general impression. The PAT Paramedic Impression completed on first contact with the patient showed “substantial agreement” (κ=0.62, 95% CI: 0.57–0.66) with the investigators’ retrospective chart review, which reflected the final diagnosis and disposition. When categorized as stable vs. unstable agreement between the PAT Paramedic Impression and PAT Investigator Impression, agreement was also “substantial” (κ=0.66, 95% CI: 0.62–0.71). The PAT Paramedic Impression for instability demonstrated a sensitivity of 77.4% (95% CI: 72.6–81.5%), a specificity of 90.0% (95% CI: 87.1–91.5%), with a positive likelihood ratio (LR+) of 7.7 (95% CI: 5.9–9.1) and a negative likelihood ratio (LR-) of 0.3 (95% CI: 0.2–0.3). The authors concluded that paramedics constructed and applied the PAT reliably, accurately predicting the instability and stability. Further, the PAT as used by paramedics was consistent with the performance of appropriate prehospital interventions.12

PAT and triageThe aim of triage is to identify patients who are more urgent. Urgency incorporates concepts of risk of deterioration and timeliness in medical assessment and treatment. Because urgency may differ between patients with the same diagnosis, triage should focus on the patient's condition at presentation instead of the diagnosis. To identify patients with such acute conditions, easy and quick assessment tools must be incorporated in triage systems.13

Currently, the most commonly used structured triage systems begin the patient's classification by an assessment of this general impression regardless of the presenting problem.14–16 Systems such as the Manchester triage system widely used in European EDs which do not include this initial assessment, have shown to be less accurate for the classification of the pediatric patient.17–21

To assess this general impression, knowledge and experience are necessary but not sufficient. The other factor found to be important is gut instinct or the sixth sense.15 As was said before, the PAT somehow summarizes “gut feeling” findings, and this makes it the ideal academic tool to teach this initial assessment.

The PAT also appears to be a potentially ideal tool to guide triage decisions because it can be applied easily and quickly, stratifying stable and unstable patients to different care pathways. The pediatric version of the Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale (PaedCTAs) uses the PAT as the initial assessment tool.16

Horeczko et al. demonstrated for the first time that a structured assessment based on PAT, performed by nurses during patient triage, rapidly and reliably identifies clinically urgent pediatric patients and their pathophysiological status. They conducted a prospective observational study where triage nurses performed the PAT on all patients presenting to the pediatric ED of an urban teaching hospital. Researchers performed blinded chart review using the physician's initial assessment and final diagnosis as the criterion standard for comparison. In their study, the PAT accurately and reliably identified acutely ill or injured infants and children in triage, as evidenced by a low negative LR for instability. Furthermore, the PAT reliably categorized unstable children by pathophysiology, as evidenced by high positive LRs for disease, thus aiding in identifying priorities of management.6

In addition, the PAT also helps to identify those patients who, after complete diagnosis and treatment in the ED, have more serious health conditions and are eventually admitted to the hospital. In a large single-center retrospective study including around 300,000 episodes classified using the PaedCTAS, Fernandez et al. analyzed the percentage of children hospitalized related to the PAT findings made by nurses at the time of triage. As secondary outcomes, they also analyzed the percentage of patients admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU), the length of stay (LOS) in the pediatric ED (<3h and ≥3h), and the percentage of patients in which blood tests were obtained in relation to PAT findings at triage. The presence of abnormal PAT findings at triage was associated with a higher probability of hospitalization (odds ratio [OR], 5.14; 95% CI, 4.97–5.32) especially in the case of appearance (OR, 7.87; 95% CI, 7.18–8.62). In the multivariate analysis, abnormal PAT findings were confirmed to be independent risk factors for hospitalization. Regarding secondary outcome measures, abnormal PAT findings, mainly appearance, and combinations of more than one component of the PAT were associated with longer LOS in the pediatric ED, and higher probability of admission to the PICU (OR for abnormal PAT 12.75; 95% CI, 10.86–14.97).22

More recently, the same group assessed the performance of the PAT along with the triage level given by PaedCTAS, a clinical score of asthma (pulmonary score), and oxygen saturation, as predictors of admission to a pediatric ED for children with asthma exacerbations. The presence of abnormal PAT findings was an independent risk factor for hospitalization (OR: 1.6, 95% CI: 1.4–1.8) and for a longer LOS (OR: 1.5, 95% CI: 1.3–1.7). Among the components of PAT, abnormal circulation to the skin was the best predictor of hospitalization (OR: 1.8, 95% CI: 1.2–2.9), whereas increased work of breathing was associated with longer LOS (OR: 1.4, 95% CI: 1.3–1.6). No relationship was found between abnormal PAT findings and PICU admission. The authors concluded that the PAT identifies patients who require more urgent treatment, helping to optimize patient flow within the pediatric ED, and also those more likely to be eventually admitted or requiring a longer stay. ED managers could use this information in real time to make decisions regarding the need for additional resources.23

Other more complex initial assessment tools, such as the Pediatric Early Warning Score (PEWS) and the Paediatric Observation Priority Score (POPS), have been assessed in the first step of the triage process. These tools incorporate measurement of vital signs. Traditionally, vital signs were considered an integral component of the initial nursing assessment and were often used as a decision making tool, but newer triage models advocate selective use of physiological parameters at triage. Vital sign measurements may be operator dependent, and the definition of normal vital signs varies according to the reference consulted. This is especially true for infancy and childhood, periods of enormous physiological and developmental change, particularly in the early months and years. There is a lack of consensus in the literature regarding normal pediatric vital sign parameters, and furthermore, most references for normal vital signs derive from studies of healthy children. Even under the best conditions, vital signs are not always reliable or accurate.1,24,25

Some trials could be found that include the Pediatric Early Warning Score (PEWS) in European EDs triage systems. The PEWS was modified from adult early warning scores to provide a reproducible assessment of a child's clinical status. The tool was developed to detect clinical deterioration in children admitted to hospital, ultimately to prevent cardiopulmonary arrest. Currently, several PEWS are being used in Europe, all of them based on the measurement of physiological parameters, with little difference between the scoring systems. In 2008 Bradman & Maconochie studied the use of a PEWS-system as a triage tool to predict hospital admission from the pediatric ED. They found that PEWS scoring in the ED had a low sensitivity and therefore had a limited value in predicting the need for admission, probably because the physiological parameters measured can be raised secondarily to pain, pyrexia, and anxiety, all common presentations in a pediatric ED.26

In 2013, Seiger et al. published a study comparing the validity of different PEWs in a pediatric ED. Although the authors found that PEWS could identify patients at risk in the ED for ICU admission and, to a lesser extent, could identify patients at risk for hospitalization, they did not advise using warning scores as triage tools to prioritize patients, because at present, there is no evidence that PEWS are better than conventional triage systems.27

In 2014, Gold et al. explored whether the PEWS utilized in an ED of an urban, tertiary care children's hospital predicted the need for ICU admission from the ED or clinical deterioration in admitted patients. Their study confirmed that, actually, an elevated PEWS is associated with need for ICU admission directly from the ED and as a transfer, but lacks the necessary test characteristics to be used independently in the ED environment. Using the optimal cutoff score to predict disposition from the ED would result in a two- to four-fold increase in intensive care unit admission rate, as well as incorrectly place roughly 25% of ICU patients on the floor. The ED is a dynamic environment, with patients frequently having alterations in physiologic parameters due to the acuity of illness or injury, medication, pain, fear, and anxiety. Such factors would result in elevated PEWS scores that do not reflect actual illness.28

The POPS includes, in addition to vital signs, subjective observation criteria, and has proven to be more suitable to use in an ED setting than PEWS. The POPS is a bespoke assessment tool for use in pediatric EDs incorporating traditional physiological parameters alongside more subjective observational criteria. It is a physiological and observational scoring system designed for use by health care professionals of varying clinical experience. POPS has demonstrated a functional ability to aid health care professionals’ decision making and has been shown to be a more accurate predictor of admission risk from the ED than PEWS.29,30

PAT and clinical practiceBeyond the clinical application of the PAT in triage, articles on its usefulness in medical practice were not found. In the aforementioned study published by Benito et al., most participants in the APLS courses acknowledged that they used the PAT approach in clinical practice and more than a half assured that their management of the critically-ill patients had improved after course completion. In addition, 82% stated that the PAT and ABCDE (Airway, Breathing, Circulation, Disability, Exposure) approaches helped them in the diagnosis and indication of the most appropriate initial treatment.9 Although this study does not give evidence on the direct impact of the PAT in clinical practice, the opinion of providers who have introduced this tool in the management of their patients appears to support its usefulness.

ConclusionsThe PAT has been incorporated, as an essential instrument for assessing sick children, into different life support courses, although little has been written about the effectiveness of teaching it.

The PAT has demonstrated to be useful to assess sick children in the prehospital setting and to make transport decisions.

In the ED, the PAT is useful to identify children at triage who require more urgent care, and recent studies have assessed and proved the efficacy of the PAT to also identify those patients having more serious health conditions who are eventually admitted to the hospital. Little has been published about performance of the PAT administered by pediatricians or emergency physicians in the initial evaluation at the ED.

The PAT is quickly spreading internationally and its clinical applicability is very promising. Nevertheless, it is imperative to promote research for clinical validation.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Fernandez A, Benito J, Mintegi S. Is this child sick? Usefulness of the Pediatric Assessment Triangle in emergency settings. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2017;93:60–7.