To evaluate idiopathic musculoskeletal pain, musculoskeletal pain syndromes, and use of electronic devices in adolescents with asthma and healthy controls.

MethodsCross-sectional study was conducted on 150 asthmatic adolescents and 300 controls. Adolescents completed a self-administered questionnaire regarding painful symptoms, use of electronic devices, and physical activity. Seven musculoskeletal pain syndromes were evaluated, and Asthma Control Test (ACT) was assessed.

ResultsMusculoskeletal pain (42% vs. 61%, p = 0.0002) and musculoskeletal pain syndromes (2.7% vs. 15.7%, p = 0.0006) were significantly lower in asthmatic adolescents than in controls. The frequency of pain in the hands and wrists was reduced in asthmatic than in controls (12.6% vs. 31.1%, p = 0.004), in addition to cell phone use (80% vs. 93%, p < 0.0001), simultaneous use of at least two electronic media (47% vs. 91%, p < 0.0001), myofascial syndrome (0% vs. 7.1%, p = 0.043), and tendinitis (0% vs. 9.2%, p = 0.008). Logistic regression analysis, including asthma with musculoskeletal pain as the dependent variable, and female sex, ACT > 20, simultaneous use of at least two electronic devices, cell phone use, and weekends and weekdays of cell phone use, as independent variables, showed that female sex (odds ratio [OR], 2.06; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.929–6.316; p = 0.0009) and ACT ≥ 20 (OR, 0.194; 95% CI, 0.039–0.967; p = 0.045) were associated with asthma and musculoskeletal pain (Nagelkerke R2 = 0.206).

ConclusionsMusculoskeletal pain and musculoskeletal pain syndromes were lower in adolescents with asthma. Female sex was associated with musculoskeletal pain in asthmatic, whereas patients with asthma symptoms and well-controlled disease reported a lower prevalence of musculoskeletal pain.

Asthma is a major public health issue with high morbidity and mortality, being one of the most common chronic inflammatory diseases in children and adolescents. Early diagnosis and treatment have an impact on the prognosis of this chronic condition, including the adolescence period.1–3

Idiopathic musculoskeletal pain is the most important cause of non-inflammatory recurrent pain in adolescents, ranging between 30% and 65%.4–9 The use of digital media (computer, internet, electronic devices, and cell phones) is a risk factor for musculoskeletal pain and musculoskeletal pain syndromes in healthy and obese adolescents.9–12

However, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, no study has evaluated musculoskeletal pain and digital media use in adolescents with asthma. In addition, no studies have systematically assessed idiopathic musculoskeletal pain syndromes, such as benign joint hypermobility syndrome, juvenile fibromyalgia, myofascial syndrome, tendinitis, bursitis, epicondylitis, and complex regional pain syndrome in adolescents with asthma.

The hypothesis of the present study is that musculoskeletal pain is frequent in asthmatic patients, particularly in females and non-controlled disease. Therefore the aim of this study was to evaluate idiopathic musculoskeletal pain, musculoskeletal pain syndromes, and the use of electronic devices in asthmatic adolescents and healthy controls.

MethodsA cross-sectional study was performed at a tertiary university hospital in the city of São Paulo, Brazil. The inclusion criteria were asthma according to GINA criteria² and adolescents with current age between 10 and 19 years. All of them were recruited between January 2017 and March 2018. The pre-established exclusion criteria were: absence of musculoskeletal inflammatory pain or musculoskeletal pain syndromes secondary to infectious, rheumatic, oncological, genetic, diabetes mellitus, or thyroid diseases, nor did these patients experience any recent trauma. The healthy control group included 300 adolescents (10–19 years of age) without chronic diseases, recruited from a public school in the same area covered by the study's hospital. The Ethics Committee of the present hospital approved this study (identification number: 1.907.909/2013). Informed consent was obtained from all adolescents and their legal guardians.

Of the 155 recruited asthma patients, three parents did not give consent and two were excluded due to recusal in the clinical examination. Thus, 150 asthmatic adolescents were assessed in this study.

All adolescents completed an anonymous and self-administered questionnaire before physician's appointment.4,5,12,13 The latest version of this questionnaire had excellent reliability in adolescents’ responses.12 The median duration of the survey answers was 20 minutes (range, 15–30 minutes). This questionnaire covered the following aspects: demographic data (age, sex, socioeconomic classes, and years of education), physical activities, musculoskeletal pain symptoms, and use of digital media (computer, internet, electronic devices, and cell phones). The electronic devices evaluated in this study were mobile handheld devices. Socioeconomic classes were classified according to the Brazilian Association of Research Companies criteria.13

Adolescents who answered “yes” to the question, “Have you had at least one pain in your muscles, bones, or joints in the past 3 months?” underwent a systematic physical examination of the musculoskeletal system by a trained physician.4,5,11,12,14 The median duration of musculoskeletal system examination was 10 minutes.

Seven musculoskeletal pain syndromes were evaluated. Juvenile fibromyalgia and benign joint hypermobility syndrome were diagnosed according to the American College of Rheumatology criteria15 and Beighton criteria,16 respectively. The myofascial syndrome was diagnosed in the presence of active trigger points evaluated bilaterally in the following specific muscles or muscular groups: trapezius, subscapular, posterior cervical muscles, biceps, triceps, brachioradial, extensor, and flexor musculature of the hand, wrist, and fingers, and intrinsic hand muscles. The clinical diagnosis of tendinitis was established based on the localized pain or tenderness upon palpation of the tendons of the shoulders, elbows, wrists, knees, and heels; bursitis according to localized pain of the bursae; and epicondylitis by localized pain or tenderness upon palpation of the epicondyles.17 Complex regional pain syndrome was diagnosed according to the Budapest criteria.18

Asthma was diagnosed according to the guidelines of the Global Initiative for Asthma (2019)2 and all 150 patients with asthma answered the Brazilian version of the validated self-administered Asthma Control Test (ACT)19 questionnaire, which contained five questions that were related to the frequency of asthma symptoms and rescue medication used during the previous 4 weeks. The ACT scores ranged between ≤19 (poor control) and ≥20 (partial/total control). Young adolescents (10–11 years of age) answered the Brazilian validated version of childhood ACT, which contained seven short-answer questions.19

Statistical analysisThe sample size provided a power of 80% to detect differences in the frequency of musculoskeletal pain among the asthmatic adolescents and healthy controls (GraphPad StatMate 1.01, GraphPad Software, Inc., CA, USA). The results for continuous variables are presented as median (minimum and maximum value) or mean ± standard deviation, and for categorical variables, as frequency (percentage). The scores that had a normal distribution were compared using Student's t-test, and those with abnormal distribution were evaluated by the Mann–Whitney U test. In the case of categorical variables, the differences were calculated using the Fisher's exact test or chi-square test, as appropriate. A logistic regression analysis (backward stepwise) was performed in asthmatic adolescents with musculoskeletal pain by including independent variables that presented a level of statistical significance of ≤ 20% in the univariate analyses. Statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.05.

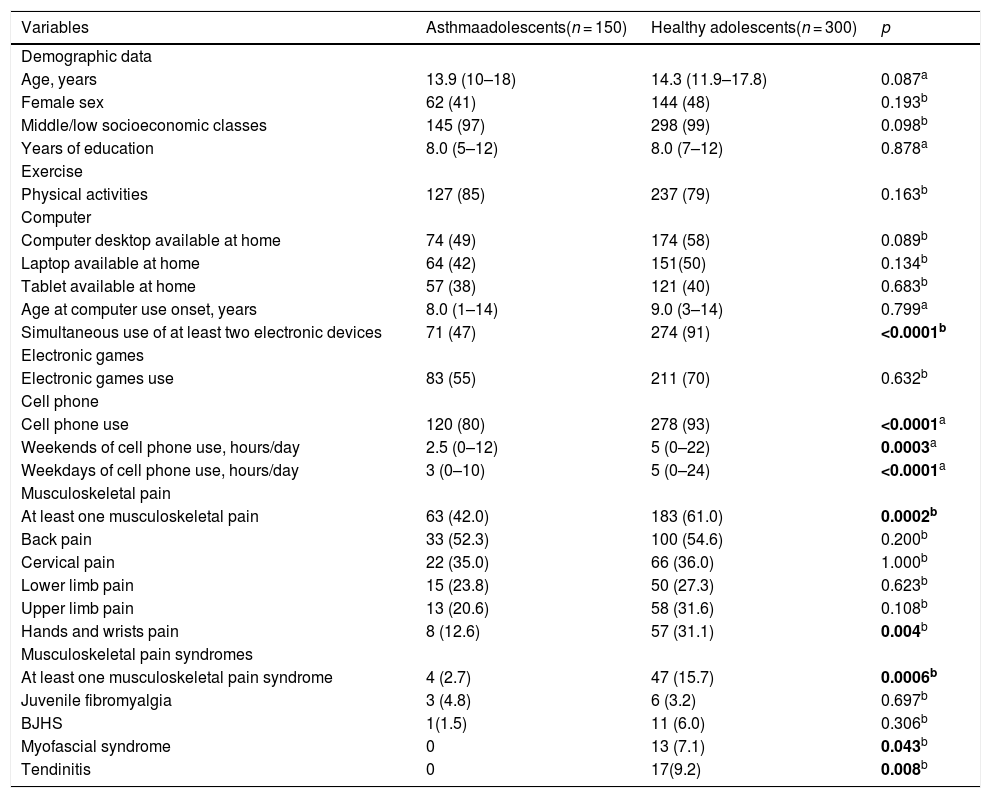

ResultsTable 1 shows the demographic data, physical activity, characteristics of computer and electronic device use, musculoskeletal pain, and musculoskeletal pain syndrome in adolescents with asthma compared to healthy adolescents. The median age was similar in asthmatic patients versus controls (13.9 years [10–18 years] vs. 14.3 years [11.9–17.8 years], p = 0.087), and years of schooling (8.0 years [5–12 years] vs. 8.0 years [7–12 years], p = 0.878). The frequencies of cell phone use (80% vs. 93%, p < 0.001) and simultaneous use of at least two electronic media (computer, electronic device, internet, and cell phone) (47% vs. 91%, p < 0.0001) were significantly lower in adolescents with asthma than in healthy adolescents. The median of weekends of cell phone use (2.5 h/day [0–12 h/day] vs. 5 h/day [0–22 h/day], p = 0.0003) and weekdays of cell phone use (3 h/day [0–10 h/day] vs. 5 h/day [0–24 h/day], p < 0.0001) were significantly lower in the former group than in the healthy adolescents.

Demographic data, physical activity, characteristics of computer and electronic game use, musculoskeletal pain and musculoskeletal pain syndrome in asthma adolescents compared to healthy adolescents.

| Variables | Asthmaadolescents(n = 150) | Healthy adolescents(n = 300) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic data | |||

| Age, years | 13.9 (10–18) | 14.3 (11.9–17.8) | 0.087a |

| Female sex | 62 (41) | 144 (48) | 0.193b |

| Middle/low socioeconomic classes | 145 (97) | 298 (99) | 0.098b |

| Years of education | 8.0 (5–12) | 8.0 (7–12) | 0.878a |

| Exercise | |||

| Physical activities | 127 (85) | 237 (79) | 0.163b |

| Computer | |||

| Computer desktop available at home | 74 (49) | 174 (58) | 0.089b |

| Laptop available at home | 64 (42) | 151(50) | 0.134b |

| Tablet available at home | 57 (38) | 121 (40) | 0.683b |

| Age at computer use onset, years | 8.0 (1–14) | 9.0 (3–14) | 0.799a |

| Simultaneous use of at least two electronic devices | 71 (47) | 274 (91) | <0.0001b |

| Electronic games | |||

| Electronic games use | 83 (55) | 211 (70) | 0.632b |

| Cell phone | |||

| Cell phone use | 120 (80) | 278 (93) | <0.0001a |

| Weekends of cell phone use, hours/day | 2.5 (0–12) | 5 (0–22) | 0.0003a |

| Weekdays of cell phone use, hours/day | 3 (0–10) | 5 (0–24) | <0.0001a |

| Musculoskeletal pain | |||

| At least one musculoskeletal pain | 63 (42.0) | 183 (61.0) | 0.0002b |

| Back pain | 33 (52.3) | 100 (54.6) | 0.200b |

| Cervical pain | 22 (35.0) | 66 (36.0) | 1.000b |

| Lower limb pain | 15 (23.8) | 50 (27.3) | 0.623b |

| Upper limb pain | 13 (20.6) | 58 (31.6) | 0.108b |

| Hands and wrists pain | 8 (12.6) | 57 (31.1) | 0.004b |

| Musculoskeletal pain syndromes | |||

| At least one musculoskeletal pain syndrome | 4 (2.7) | 47 (15.7) | 0.0006b |

| Juvenile fibromyalgia | 3 (4.8) | 6 (3.2) | 0.697b |

| BJHS | 1(1.5) | 11 (6.0) | 0.306b |

| Myofascial syndrome | 0 | 13 (7.1) | 0.043b |

| Tendinitis | 0 | 17(9.2) | 0.008b |

Results are presented in number (%) and median (minimum and maximum values).

BJHS, benign joint hypermobility syndrome.

The presence of at least one musculoskeletal pain syndrome was significantly lower in adolescents with asthma than in healthy controls (63/150 [42%] vs. 183/300 [61%], p = 0.0002). The main locations of reported musculoskeletal pain were the back (33/150, 52.3%), cervical region (22/150, 35%), lower limb (15/150, 23.8%), and upper limb (13/150, 20.6%). Eighteen of the 63 evaluated (28.5%) adolescents with asthma and musculoskeletal pain had complaints in more than one location. The frequency of pain in the hands and wrists was significantly lower in asthmatic adolescents than in healthy controls (12.6% vs. 31.1%, p = 0.004), whereas back pain, cervical pain, lower limb pain, and upper limb pain were similar in both groups (p > 0.05). Bursitis, epicondylitis, or complex regional pain syndrome were not observed in adolescents in both groups (Table 1).

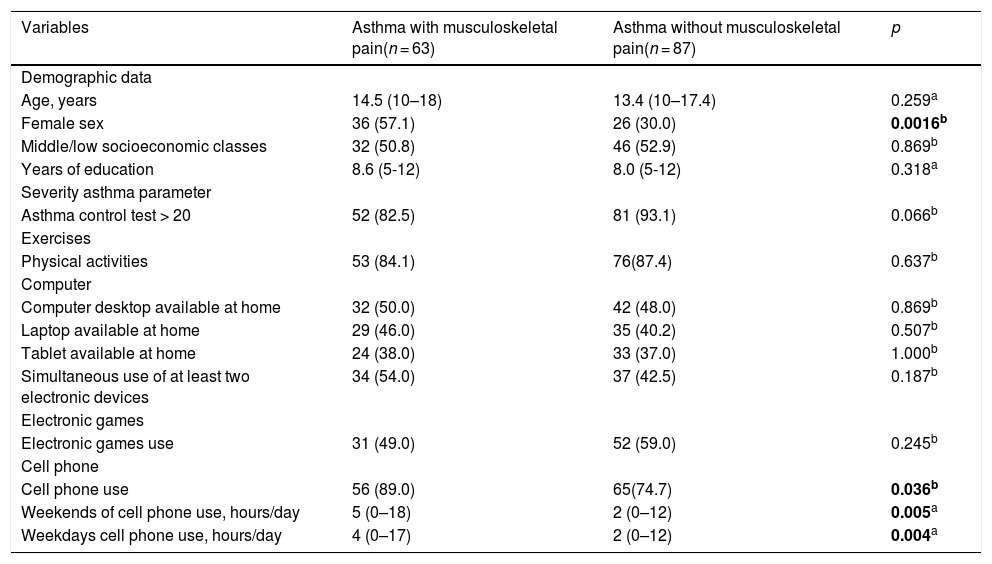

Table 2 illustrates the demographic data, physical activity, and use of digital media in 150 asthmatic adolescents with and without musculoskeletal pain in the last 3 months. The frequency of female patients was significantly higher in asthmatic adolescents with musculoskeletal pain than in those without musculoskeletal pain (57.1% vs. 30.0%, p = 0.0016). Cell phone use (89.0% vs. 74.7%, p = 0.036) was significantly higher in asthmatic adolescents with musculoskeletal pain than in those without musculoskeletal pain. Furthermore, the median of weekends of cell phone use (5 h/day [0–18 h/day] vs. 2 h/day [0–12 h/day], p = 0.005) and weekdays of cell phone use (4 h/day [0–17 h/day] vs. 2 hours/day [0–12 h/day], p = 0.004) were significantly higher in the group with musculoskeletal pain.

Demographic data, physical activity and use of digital media in 150 asthma adolescents with and without musculoskeletal pain in the last three months.

| Variables | Asthma with musculoskeletal pain(n = 63) | Asthma without musculoskeletal pain(n = 87) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic data | |||

| Age, years | 14.5 (10–18) | 13.4 (10–17.4) | 0.259a |

| Female sex | 36 (57.1) | 26 (30.0) | 0.0016b |

| Middle/low socioeconomic classes | 32 (50.8) | 46 (52.9) | 0.869b |

| Years of education | 8.6 (5-12) | 8.0 (5-12) | 0.318a |

| Severity asthma parameter | |||

| Asthma control test > 20 | 52 (82.5) | 81 (93.1) | 0.066b |

| Exercises | |||

| Physical activities | 53 (84.1) | 76(87.4) | 0.637b |

| Computer | |||

| Computer desktop available at home | 32 (50.0) | 42 (48.0) | 0.869b |

| Laptop available at home | 29 (46.0) | 35 (40.2) | 0.507b |

| Tablet available at home | 24 (38.0) | 33 (37.0) | 1.000b |

| Simultaneous use of at least two electronic devices | 34 (54.0) | 37 (42.5) | 0.187b |

| Electronic games | |||

| Electronic games use | 31 (49.0) | 52 (59.0) | 0.245b |

| Cell phone | |||

| Cell phone use | 56 (89.0) | 65(74.7) | 0.036b |

| Weekends of cell phone use, hours/day | 5 (0–18) | 2 (0–12) | 0.005a |

| Weekdays cell phone use, hours/day | 4 (0–17) | 2 (0–12) | 0.004a |

Results are presented in number (%) and median (minimum and maximum values).

Further logistic regression analysis, including asthma with musculoskeletal pain as the dependent variable, and female sex, ACT ≥ 20, simultaneous use of at least two electronic devices, cell phone use, weekends of cell phone use, and weekdays of cell phone use as independent variables, showed that female sex (odds ratio [RO], 2.06; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.929–6.316; p = 0.0009) and ACT ≥20 (OR, 0.194; 95% CI, 0.039–0.967; p = 0.045) were associated with asthma and musculoskeletal pain (Nagelkerke R2 = 0.206).

DiscussionThe authors demonstrated that female sex was associated with musculoskeletal pain in asthmatic adolescents, whereas patients with asthma symptoms and well-controlled disease reported a lower incidence of musculoskeletal pain.

The main strength of this study was the anonymous, self-reported, and standardized survey, including figures of different body parts, to show the multiple localizations of musculoskeletal pain.12 The exclusion of inflammatory or mechanical etiologies of musculoskeletal pain, particularly infectious, rheumatic, oncological, and recent trauma were relevant, since these conditions may induce recurrent and chronic pain, even in patients with mild alterations in the physical examination. Another strength of this study was the assessment of seven diffuse or localized frequent musculoskeletal pain syndromes in adolescents. ACT evaluation is also important since this score can help physicians to determine if asthma symptoms are well-controlled.1,2,9,20

Approximately 40% of asthmatic adolescents presented with musculoskeletal pain, mainly back and cervical pain. Another study using the same questionnaire found recurrent and non-inflammatory musculoskeletal pain in 44% of obese adolescents, particularly lower limb pain.4 This non-inflammatory musculoskeletal pain is generally underdiagnosed and can interfere with daily life activities.

Hand and wrist pain were lower in adolescents with asthma than in healthy controls. The reduced cell phone use and simultaneous use of at least two electronic devices may have contributed to these specific musculoskeletal pains, since the digital media may induce acute and chronic musculoskeletal stress and overuse.5,14

Queiroz et al.18 evaluated adolescents of a private school in the city of São Paulo and observed 61% of musculoskeletal pain. These findings were similar to another study in a private school of Recife, that reported 65% of musculoskeletal pain.5,14 Rebolho et al.21 evaluated students from public schools aged 7 to 11 years in the city of São Paulo and found complaints of back pain in 34%, predominantly in boys. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this was the first study to show lower frequencies of musculoskeletal pain and musculoskeletal pain syndromes, particularly tendinitis and myofascial syndrome, in adolescents with asthma compared to healthy controls.

Musculoskeletal pain was marked in female adolescents, as described in other studies.5,7,12,14 These findings may be related to the fact that women complain more about pain than men. Additionally, the present study showed that the control of chronic and prevalent diseases, such as asthma, could reduce the perception of musculoskeletal pain, even in adolescents using multiple electronic devices. Further longitudinal studies are required to assess the perception of musculoskeletal pain and asthma control to confirm this hypothesis.

Musculoskeletal pain syndromes are one of the main reasons for referral in pediatric patients. These non-inflammatory syndromes, especially juvenile fibromyalgia and benign joint hypermobility syndrome, are rarely observed in adolescents with asthma. Patients with fibromyalgia may have a different perception of pain and may have difficulty in reporting symptoms of dyspnea.20–23 These syndromes can negatively influence physical, academic, and psychosocial functions; therefore, pediatricians must be aware of how to diagnose and treat these chronic conditions.

The present study has several limitations. This study had a cross-sectional design; therefore, causal relationships could not be affirmed. Another limitation of the study is the external validity of the data since this was not population-based, including only asthmatics patients selected from a specialized center in a tertiary hospital. Indeed, the absence of comparison with individuals from a community may have induced selection bias. Another limitation was the absence of an evaluation of medication use in the asthmatic group. These patients were followed up at a tertiary university asthma center, and the vast majority of patients used control medication, either inhaled corticosteroids or associated with long-acting beta-2, and received all medications free of charge. Although the authors did not include the medication data received in the study, most of the controlled or uncontrolled cases used prophylactic medication. Other factors contributing to musculoskeletal pain and musculoskeletal pain syndromes, such as psychosocial functioning,23,24 sleep abnormalities, backpack use, body posture, ergonomic assessment, and corticosteroids doses, were not systematically studied.7-9

In conclusion, musculoskeletal pain and musculoskeletal pain syndromes were lower in adolescents with asthma than in healthy controls. The low use of electronic equipment in asthma patients seems to contribute to the low prevalence of these findings. Female sex was associated with musculoskeletal pain in asthmatic adolescents, whereas patients with asthma symptoms and well-controlled disease reported a lower prevalence of musculoskeletal pain.