To study the occurrence of alexithymia in obese adolescents.

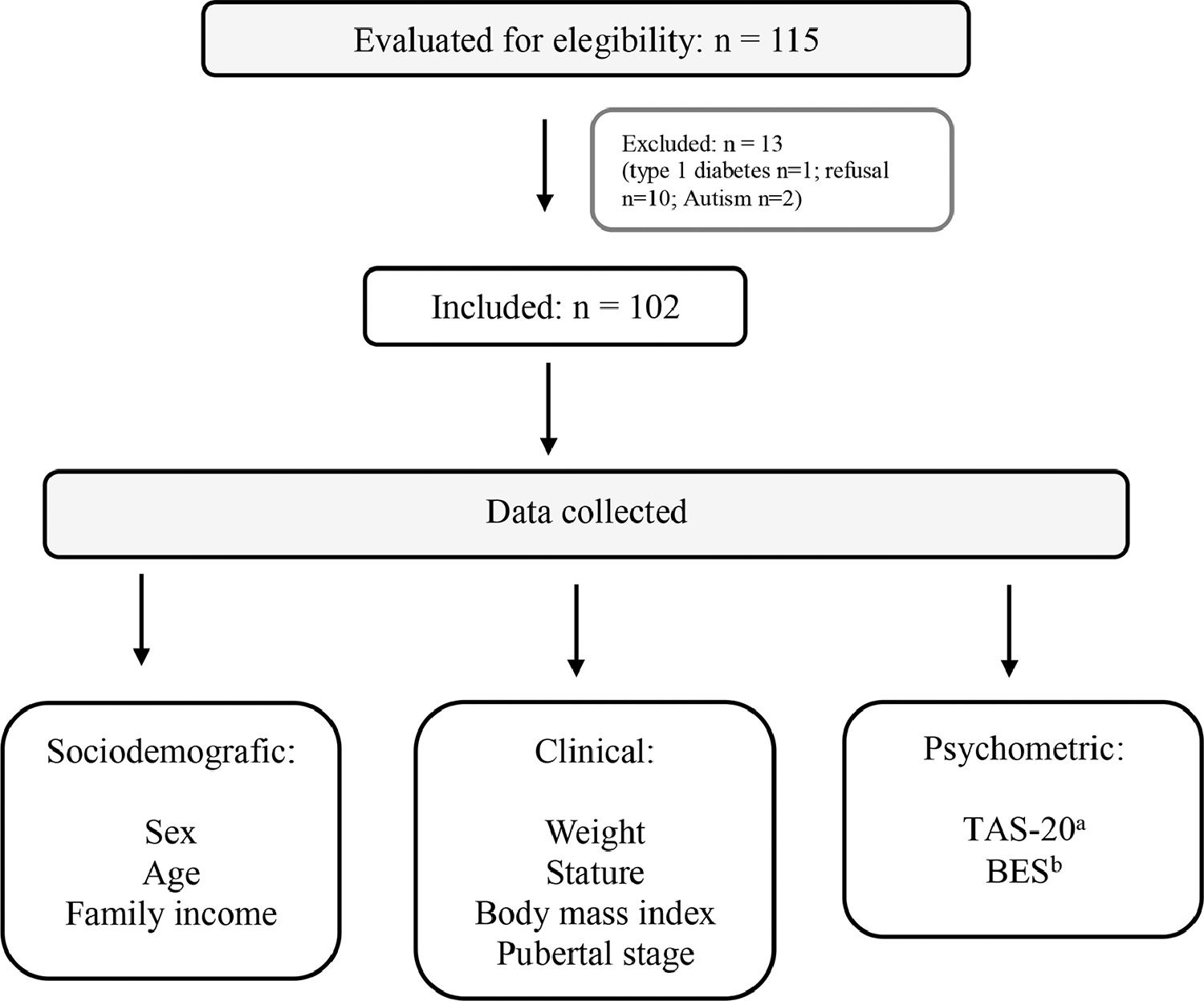

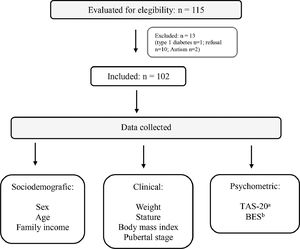

MethodsCross-sectional study with 102 obese adolescents. Sociodemographic, clinical, and psychometric data (alexithymia and binge eating) were analyzed The Brazilian version of the Toronto Alexithymia Scale and Binge Eating Scale were used for psychometric data collection. Statistical analysis was performed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, Student's t-test, ANOVA, chi-square, linear regression, and logistic regression. The study was approved by Research Ethics Committee.

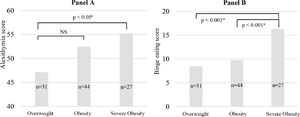

ResultsA 22% occurrence of alexithymia was observed. Considering the category “possible alexithymia”, half of the participants presented some alexithymic behavior. Adolescents with alexithymia had higher binge eating scores (alexithymia 16,2 versus possible alexithymia 11,7 versus no alexithymia 8,5; ANOVA p < 0,0005) and three times more binge eating behavior than adolescents with no alexithymia or possible alexithymia (alexithymia 36.4% versus 17.2% possible alexithymia versus 11.8% no alexithymia; chi-square = 6,2, p = 0.04). In simple linear regression, alexithymia scores were positively associated with binge eating scores (r2 = 0,4; p = 0,002). Binary logistic regression showed a three times higher probability of an adolescent with severe obesity to meet the criteria for alexithymia.

ConclusionsThere was a 22% occurrence of alexithymia in obese adolescents. It was positively associated with obesity severity and higher binge eating scores, suggesting a relationship between severe obesity, alexithymia, and binge eating behavior.

Obesity is one of the most common chronic noncommunicable diseases in adolescence. It has considerable health impacts in adolescence and adulthood such as the appearance of metabolic and chronic-degenerative diseases, especially in cases where the disease is considered severe. Obesity has a multifactorial and complex etiology with biological, environmental, and emotional components.1

Emotion regulation is an ability developed in childhood, its function is to control impulses and affective processes. Emotional regulation can be influenced by negative experiences early in life, often leading to a higher food intake, even in the absence of hunger, in an attempt to regulate and reduce negative emotions like sadness and anxiety.2,3 Emotional eating is the tendency to eat in response to any emotions. A causal relationship between negative mood and greater food intake has previously been described in clinical4 and general populations.5 Some individuals cannot regulate their emotions effectively. These individuals have difficulties identifying, processing, and describing feelings, all of which characterize an alexithymic personality.6 In alexithymic individuals, negative feelings may trigger a somatic response like excessive food intake, considered an emotional eating pattern.7 The binge eating behavior, a loss of control over eating with episodes of rapid consumption of large amounts of food,8 is also related to emotional eating.4,5,9 When binge eating episodes are recurrent (at least once a week for three months), a binge eating disorder may be present.10

The term alexithymia comes from the Greek a (no), lexis (word) and timia (affection),11 meaning “no words for emotions”. Alexithymia involves three defining characteristics: difficulty in adopting appropriate language to describe and express feelings as different from body sensations, reduced capacity to imagine and fantasize, and a concrete cognitive style focused on the external environment.6 The etiology of alexithymia seems to involve genetic, physiological, psychosocial, neurochemical, and neuroanatomical factors.11 In people with obesity, alexithymic behavior may appear more frequently as a mechanism to deal with stressor agents.12

There are little data in the literature about alexithymic behavior in obese adolescents. A study addressed specifically to obese adolescents describes a 15% occurrence of alexithymia in a group of 56 female adolescents with obesity aged 12−17 years.13 In adults, alexithymia was significantly more frequent among obese patients compared to control subjects.14

Thus, the aim of this study is to evaluate the presence of alexithymic behavior in obese adolescents by analyzing possible associations with clinical and sociodemographic profiles and binge eating behavior.

MethodsSubjectsThis is a cross-sectional study in a group of obese adolescents attending a two secondary outpatient clinic from the Brazilian Unified Health System (SUS) in the city of Blumenau, SC. The subjects were sequentially included adolescents who attended medical appointments between June 2017 and February 2018 for treatment of obesity. Exclusion criteria were the presence of dietary restrictions due to illness, short stature (Z-score < −2), genetic syndrome, neurological disease, endocrine disease (hypothyroidism, Cushing's disease, growth hormone deficiency, Type 1 diabetes), or refusal to participate (Fig. 1). Before medical appointments, two trained interviewers applied psychometric tests and collected sociodemographic data while clinical variables were collected from medical records (Fig. 1).

AssessmentSociodemographic dataSex (female or male), age (10–14 or 15–19 years), and family income categorized into one of the following: low socioeconomic status (income ≤ R$ 2,673.00), middle socioeconomic status (income between R$ 2,674.00 and R$ 9,896.00) and high socioeconomic status (income ≥ R$ 9,897.00) (Secretaria de Assuntos Estratégicos – SAE, 2018).

Clinical dataAnthropometric data, pubertal stage, and degree of obesity. Bodyweight and stature were measured using an anthropometric scale, and body mass index (BMI) obtained through Quetelet index and transformed into Z-score (BMI Z-score). It was considered overweight a BMI Z-score between +1 and +2, obesity a BMI Z-score between +2 and +3, and severe obesity a BMI Z-score higher than +3 according to World Health Organization criteria. The pubertal stage was evaluated by Tanner criteria and categorized in pre-pubertal and pubertal. The presence of breast development in girls and gonadal development in boys was considered puberty.

Psychometric dataAlexithymia was assessed using the Brazilian version of the Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20).15 This instrument contains 20 phrases related to moods and emotions. Each question is assessed by the 5-point Likert scale. Cutoff points are alexithymia (score ≥ 61), possible alexithymia (score between 52 and 60) and absence of alexithymia (score ≤ 51). Binge eating was estimated using the Brazilian version of the Binge Eating Scale (BES).16 This instrument consists of 16 questions and has the following cutoff points: absence of binge eating (score ≤ 17), moderate binge eating (score between 18 and 26) and severe binge eating (score ≥ 27). For statistical analysis, moderate binge eating, and severe binge eating were grouped into a single category titled “with binge eating”.

Statistical analysis and ethical proceduresDescriptive statistics were used to present results. All variables had parametric distribution by Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. A student's t-test and ANOVA with Tukey-Kramer were used to compare clinical, sociodemographic, and psychometric data between alexithymia and obesity severity. Chi-square test was used to access differences in the occurrence of alexithymia by age range, sex, the severity of obesity, presence of binge eating, family income, and pubertal stage. Multivariate binary logistic regression was used in multivariate analysis. The level of significance adopted was p < 0.05. The database was built in Excel® program and statistical analyses were performed using StatPlus® and EPIINFO version 7. The study was approved by the Human Ethics Committee of the Regional University of Blumenau (CAAE: 22787213.3.0000.5370 /1.902.652) and all participants signed the Free and Informed Consent Form.

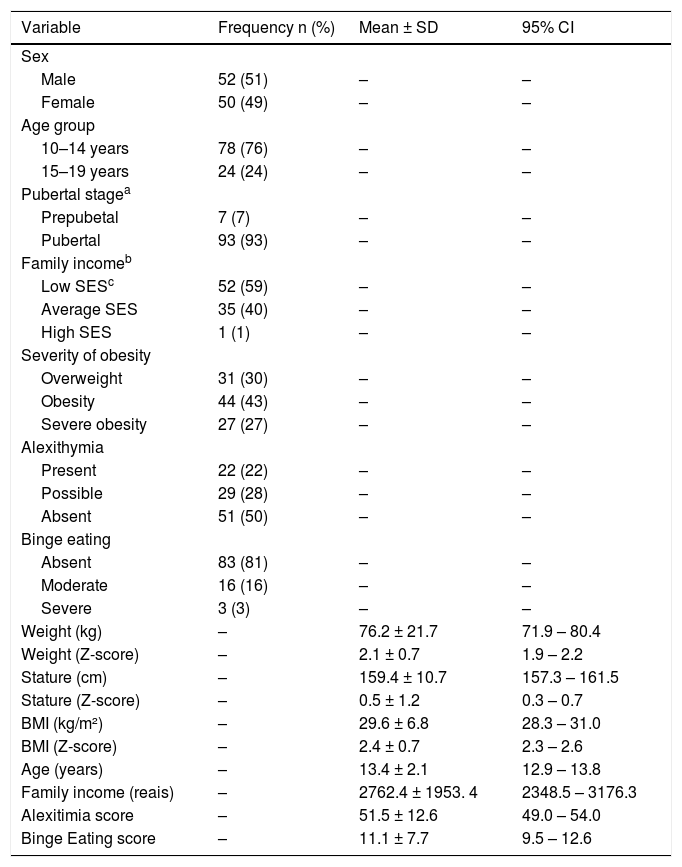

ResultsTable 1 presents descriptive data of participants. There was an occurrence of 22% (n = 22) of alexithymia and 28% (n = 29) of possible alexithymia. Patients with severe obesity had twice the occurrence of alexithymia compared to overweight adolescents (overweight 34% versus obesity 49% versus severe obesity 70%; chi-square = 7.6; p < 0.05).

Characteristics of participants.

| Variable | Frequency n (%) | Mean ± SD | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Male | 52 (51) | – | – |

| Female | 50 (49) | – | – |

| Age group | |||

| 10–14 years | 78 (76) | – | – |

| 15–19 years | 24 (24) | – | – |

| Pubertal stagea | |||

| Prepubetal | 7 (7) | – | – |

| Pubertal | 93 (93) | – | – |

| Family incomeb | |||

| Low SESc | 52 (59) | – | – |

| Average SES | 35 (40) | – | – |

| High SES | 1 (1) | – | – |

| Severity of obesity | |||

| Overweight | 31 (30) | – | – |

| Obesity | 44 (43) | – | – |

| Severe obesity | 27 (27) | – | – |

| Alexithymia | |||

| Present | 22 (22) | – | – |

| Possible | 29 (28) | – | – |

| Absent | 51 (50) | – | – |

| Binge eating | |||

| Absent | 83 (81) | – | – |

| Moderate | 16 (16) | – | – |

| Severe | 3 (3) | – | – |

| Weight (kg) | – | 76.2 ± 21.7 | 71.9 – 80.4 |

| Weight (Z-score) | – | 2.1 ± 0.7 | 1.9 – 2.2 |

| Stature (cm) | – | 159.4 ± 10.7 | 157.3 – 161.5 |

| Stature (Z-score) | – | 0.5 ± 1.2 | 0.3 – 0.7 |

| BMI (kg/m²) | – | 29.6 ± 6.8 | 28.3 – 31.0 |

| BMI (Z-score) | – | 2.4 ± 0.7 | 2.3 – 2.6 |

| Age (years) | – | 13.4 ± 2.1 | 12.9 – 13.8 |

| Family income (reais) | – | 2762.4 ± 1953. 4 | 2348.5 – 3176.3 |

| Alexitimia score | – | 51.5 ± 12.6 | 49.0 – 54.0 |

| Binge Eating score | – | 11.1 ± 7.7 | 9.5 – 12.6 |

SD, Standard deviation, CI, Confidence interval, BMI, Body mass index.

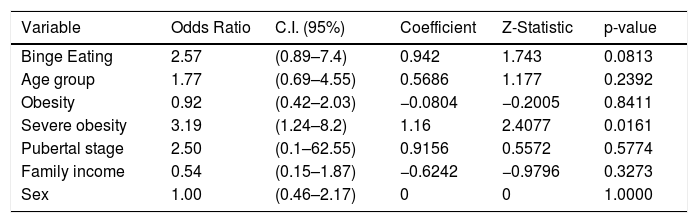

Adolescents with alexithymia presented three times more binge eating behavior compared to adolescents with possible alexithymia or without alexithymia (36.4% versus 17.2% versus 11.8% respectively; chi-square = 6,2, p = 0.04). In multivariate binary logistic regression, the final model was summarized in a simple binary logistic regression where severe obesity was significant. The model showed a three times higher probability of an adolescent with severe obesity to meet the criteria for alexithymia (Table 2). There was no association between the presence of alexithymia and the categories of sex, pubertal stage, age group, and family income.

Simple binary logistic regression.

CI, Confidence interval.

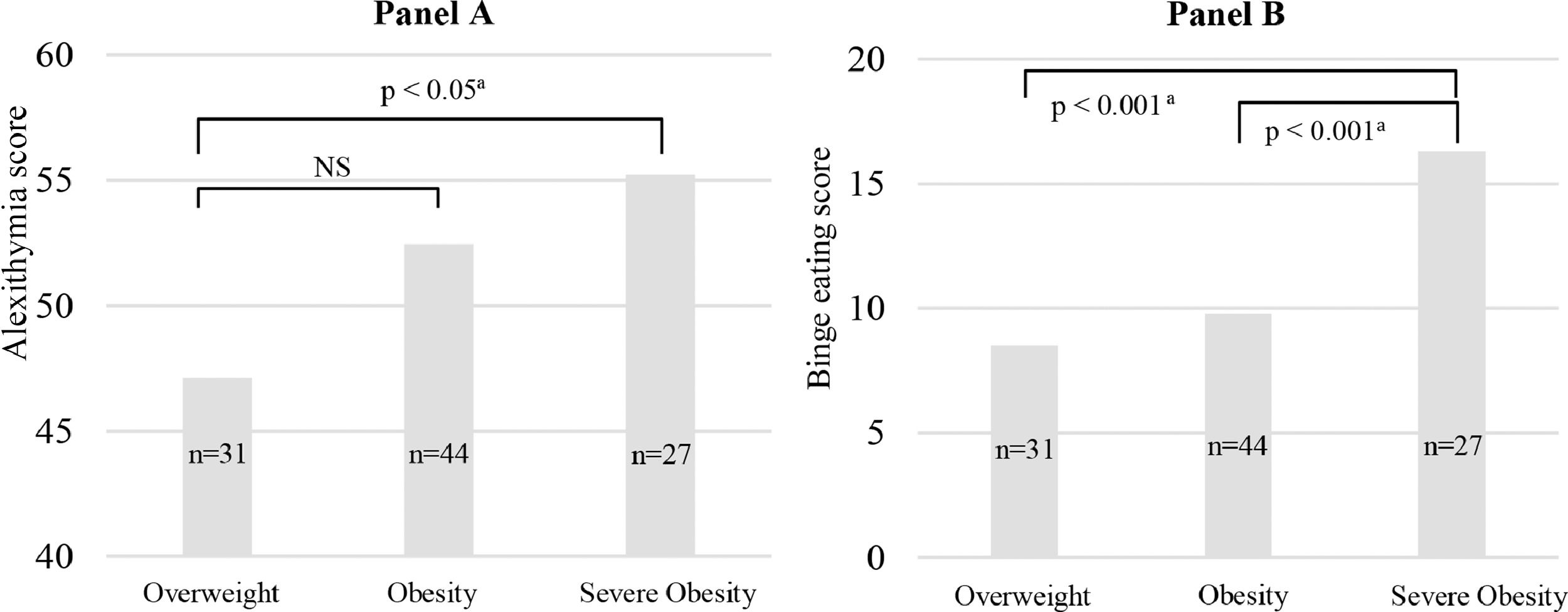

Alexithymia and binge eating scores increased progressively throughout categories of obesity severity. Adolescents with severe obesity had higher scores for alexithymia and binge eating (Fig. 2), suggesting a continuum of emotional and uncontrolled eating in relation to the obesity severity.

DiscussionThe present study evaluated alexithymia in adolescents with obesity, finding a 22% occurrence of alexithymia, higher than that described before.13 Considering participants with “possible alexithymia”, 50% presented some alexithymic behavior. The higher occurrence of alexithymia observed compared to the previous study may be explained by the difference in participants’ profiles, which were predominantly obese in this study in contrast to majoritarily overweight in the previous. Alexithymic behaviors are being considered a risk factor for the development of eating disorders, especially binge eating disorder,17 and seems to be related to food addiction, a condition present in a subpopulation of individuals experiencing substance-dependence symptoms toward specific foods.18 Difficulties in identifying emotions and/or describing feelings may result in overeating during stressful periods, a strategy used to deal with negative emotions in adults9 and adolescents19 with obesity.

Alexithymic behavior may be a possible trigger for binge eating behavior in adolescents with obesity. Cognitive deficits that occur during the process of differentiating feelings from bodily sensations like hunger or satiety may explain this interrelation.20 In fact, an association was found between alexithymia and binge eating behavior. This is the first study to demonstrate this association in adolescents with obesity. Alexithymic behavior is more frequent in adult individuals with binge eating disorders.21 In adult women, alexithymia mediates the relationship between childhood neglect and disordered eating symptoms like binge eating.3 It seems that individuals that present binge eating behaviors have trouble describing their feelings and find comfort in food during certain emotional situations. Most difficulties in identifying and regulating emotions do not seem to be associated with obesity itself, but with the psychopathology of binge eating disorder.22

The observed association between alexithymia score and obesity severity highlights the role of emotional dysregulation in severe obesity during adolescence. In a group of people of different ages diagnosed with obesity or anorexia nervosa, it was observed that obese participants had more difficulty in identifying negative emotions. Both children and adults with obesity present mental rigidity and difficulties in shifting attention.23 Neuroscience studies have demonstrated weak responses in brain structures necessary for the representation of emotion used in conscious cognition and stronger autonomic responses. Consequently, people with alexithymia present inflexible emotional guiding decision making.24

A positive association was found between the presence of alexithymia, the presence of binge eating and obesity severity. These findings suggest that alexithymia, when present, can cause an abnormal progressive increase in body weight resulting in severe obesity over time. The alexithymic adolescent, in face of their difficulties in identifying and verbalizing feelings, starts the process of overeating, sometimes accompanied by binge eating, to ameliorate a negative emotional state. Adolescents with alexithymia experience more loss of control eating and eating in the absence of hunger.25

Alexithymia also may play a role in the maintenance of obesity. In adults, the presence of alexithymia was associated with severe obesity.26 Individuals with severe obesity and alexithymia who underwent bariatric surgery present lower weight loss at 12 months after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy than non-alexithymic individuals.27 Many individuals with alexithymia have inaccurate perceptions of their body weight, such as the severity of obesity, and have different reactions in dealing with visual food stimulations.26 A historical pattern of emotional eating throughout life cycles is considered a negative factor for therapeutic success in obesity.27

The authors of the present study recommend considering the systematic approach to emotional eating in adolescents with severe obesity. Identification of alexithymia allows a specific intervention on emotional health in order to improve emotional regulations and, consequently, result in therapeutic success. Recently, a systematic review pointed out the impact of emotional eating in overeating behaviors in children and adolescents. There is longitudinal data demonstrating a negative association between maladaptive emotional regulation and being overweight.28 This approach could identify and treat precociously alexithymic behavior in younger individuals before it turns into a binge eating disorder later in life.

As a limitation of this study, the authors mention data transversality and non-probabilistic sample. Data transversality hinders the establishment of a temporal relationship between events and causality, and a non-probabilistic sample does not guarantee a representative sample of adolescents with obesity. However, despite limitations in generalizing results, a non-probabilistic sample can be useful and even preferable in some situations as in homogeneous samples like in this study.

ConclusionsA 22% occurrence of alexithymia was found in obese adolescents. It was positively associated with severity of obesity and binge eating scores, suggesting a relationship between severe obesity, alexithymia, and binge eating behavior. Severely obese adolescents showed a three times higher probability to meet the criteria for alexithymia.

Difficulty in regulating emotions should be considered in the clinical evaluation and monitoring of adolescents with severe obesity, especially in those with difficulties in achieving weight loss. The affective dimension of alexithymia could be a target in the treatment of emotional regulation in this group of adolescents.