To evaluate height, sexual maturation, and the difference between final and expected height in girls with juvenile idiopathic arthritis and no glucocorticoid treatment for at least six months, as compared to a group of healthy girls.

MethodsThis cross-sectional study involved 44 girls with juvenile idiopathic arthritis, diagnosed according to the International League of Associations for Rheumatology criteria, and 59 healthy controls aged between 8 and 18 (incomplete) years with no comorbid chronic diseases. Demographic data were collected from all participants, and disease and treatment variables were compiled for the patient group. Anthropometric measurements were converted into Z-scores based on World Health Organization standards. Sexual maturation was classified according to Tanner stages.

ResultsBody mass index and height Z-scores were lower in girls with juvenile idiopathic arthritis as compared to control participants. These values differed significantly in Tanner stage II. Three (6.8%) girls with juvenile idiopathic arthritis had height-for-age Z-scores <−2 (short stature). Girls with polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis and higher cumulative glucocorticoid doses were significantly more likely to present with short stature. The percentage of prepubertal girls in the juvenile idiopathic arthritis group was significantly higher than that observed in the control group, (p=0.012). Age of menarche, adult height, and the difference between actual and expected height did not differ between groups.

ConclusionThese findings suggest that even six months after the suspension of glucocorticoid treatment, children with polyarticular/systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis subtypes are still susceptible to low height and delayed puberty.

Avaliar a estatura, maturação sexual e a diferença entre a estatura final e a esperada em meninas com artrite idiopática juvenil (AIJ) sem tratamento com glicocorticoides por pelo menos seis meses, em comparação com um grupo de meninas saudáveis.

MétodosEste estudo transversal avaliou 44 meninas com artrite idiopática juvenil, diagnosticadas de acordo com os critérios da International League of Associations for Rheumatology e 59 controles saudáveis, entre oito e 18 anos (incompletos) sem comorbidades por doenças crônicas. Os dados demográficos foram coletados de todos os participantes e as variáveis de doença e tratamento foram compiladas para o grupo de pacientes. As medidas antropométricas foram convertidas em escores-z com base nos padrões da Organização Mundial da Saúde. A maturação sexual foi classificada de acordo com os estágios de Tanner.

ResultadosÍndice de massa corporal e escores-z de estatura foram menores em meninas com artrite idiopática juvenil em comparação com os participantes-controle. Esses valores diferiram significativamente no estágio II de Tanner. Três (6,8%) meninas com artrite idiopática juvenil tinham escores-z de estatura para idade<-2 (baixa estatura). Meninas com artrite idiopática juvenil poliarticular e doses cumulativas de glicocorticoides foram significativamente mais propensas a apresentar baixa estatura. A porcentagem de meninas pré-púberes no grupo artrite idiopática juvenil foi significativamente maior do que a observada no grupo controle (p=0,012). A idade da menarca, a estatura adulta e a diferença entre a estatura real e a esperada não diferiram entre os grupos.

ConclusãoEsses achados sugerem que, mesmo após seis meses da suspensão do tratamento com glicocorticoides, as crianças com os subtipos poliarticular/sistêmico de AIJ ainda são suscetíveis a baixa estatura e atraso na puberdade.

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is a heterogeneous group of diseases with onset before the age of 16 years and joint inflammation as a main feature.1 It is a chronic, inflammatory, and progressive disease mediated by cytokines – interleukin 6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), and interleukin 1 beta (IL-1ß) – produced during the inflammatory process and affecting various body systems.1–3

The etiology of delayed growth in children with JIA is multifactorial and strongly associated with prolonged inflammatory activity, since proinflammatory cytokines, especially IL-6, reduce pituitary growth hormone secretion and act directly on the growth plate of long bones.4–6 Other factors such as malnutrition and glucocorticoid treatment may also be implicated in this phenomenon.7,8 According to the literature, the incidence of disturbed growth, that is, height-for-age below the 3rd percentile or <−2 SD, ranges from 10% to 40% in patients with JIA, and is more severe in those with polyarticular or systemic forms of the disease, as well as in children with more severe joint damage.9–11

A few recent studies have found that two to three years after the control of disease activity and the suspension of glucocorticoid treatment, some patients may restore their genetic growth potential and nearly achieve their expected final height.11–13 High levels of glucocorticoids are known to inhibit longitudinal bone growth by acting directly on the growth plate; however, this may also delay growth plate senescence and decrease chondrocyte proliferation, which may explain the phenomenon of catch-up growth after treatment suspension.14,15

Chronic diseases in childhood may delay puberty, especially if they have a prepubertal onset or are so prolonged and severe as to lead to chronic and intense malnutrition.15,16

Delayed puberty may be defined as the lack of pubertal development at an age of 2 standard deviations above the mean, which corresponds to an age of approximately 13 years old for girls (breast development being the first signal).16–19

The aims of this study were to evaluate height and sexual maturation in girls with JIA and no glucocorticoid treatment for at least six months, as compared to a group of healthy girls, as well as to analyze the difference between final and expected height in girls with JIA and control subjects with more than two years post-menarche.

MethodsThis was a cross-sectional study performed between August 2013 and July 2015, involving patients from the Departments of Pediatric Rheumatology of the Hospital. Two participant groups were recruited: one consisting of girls with JIA, and a control group of healthy girls. All participants were aged between 7 and 18 (incomplete) years and received no glucocorticoid treatment in the six months preceding the study. Patients with JIA were classified according to the 2001 International League of Associations for Rheumatology (ILAR) guidelines1 and had been diagnosed for at least one year. Participants with any chronic diseases in addition to arthritis were excluded from the study.

Clinical assessmentAfter written consent was obtained from participants and/or guardians, the following epidemiological data were collected from both patients and control subjects: age, years of education, age of menarche (if applicable), maternal age, maternal and paternal height, and age of maternal menarche.

In the JIA group, additional data were collected regarding the patients’ current and past medical history (subtype of JIA, age of disease onset, date of diagnosis, medications used, current medication, and dosage). Disease activity and cumulative glucocorticoid and methotrexate doses were also measured.

JIA activityJIA activity was measured using the Disease Activity Score (DAS 28) developed by Prevoo in 1995,20 which evaluates the following parameters: 28-joint counts measuring tender and swollen joints, laboratory tests of inflammatory activity (C-reactive protein [CRP] or blood sedimentation rate) and general health (10-cm visual analog scale) These scores are then used to classify disease activity as mild (DAS 2.8≤3.2), moderate (3.2–5.1), or high (>5.1). Scores below 2.6 are indicative of remission.

Cumulative glucocorticoid doseThis variable was calculated as the total sum of daily glucocorticoid doses received by the patient over the course of treatment, according to their electronic medical records. The value was adjusted for the body surface area.

Cumulative methotrexate doseThis was calculated based on the weekly dose of methotrexate received by each patient (orally or parenterally), according to their electronic medical records.

Patients with JIA were divided into two groups according to the number of affected joints. Those with four or less joints affected were classified into the oligoarticular disease group, while those with five or more joints involved were classified as having polyarticular arthritis. Patients with systemic JIA who evolved into polyarticular disease were included in this group.

Anthropometric assessmentAll anthropometric measurements were collected by the same investigator (SHM) and evaluated based on World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines. Patients were weighed on an electronic scale (Filizola® – Porto Alegre, Brazil) accurate to 0.1g with a maximum capacity of 150kg, while barefoot and wearing a standard hospital gown. Height was measured using a stadiometer attached to the weighing scale, accurate to 0.1cm, with a maximum length of 200cm. Each subject was tested barefoot, with feet together and heels against the wall. Height measurements were rounded to the nearest 0.5cm. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing body mass in kg by height in m2. This value was then converted into age-adjusted Z-scores.

Final height was measured in all girls who were at least two years post-menarche and were in Tanner stages IV or V. Target height was estimated using the following formula: (mother's height (measured)+father's height (reported) – 13)/2cm. The Δ target height (father/mother) was calculated as the difference between the subject's final height and the expected target height.

Pubertal stagingPubertal stages were determined performed by visual inspection using Tanner's criteria defined as follows: stage I – no breast bud or pubic hair; stage II – breast bud present,21 small amount of long, downy hair with slight pigmentation on the genitalia; stage III – breast becomes more elevated, pubic hair becomes more coarse and curly; stage IV – areola and papilla project from the surrounding breast, adult-like pubic hair quality; stage V – breast reaches final adult size, pubic hair resembles adult in quantity and type. All girls were examined alone or with their mothers, according to their privacy preferences. Pubertal stages were determined based on breast and pubic hair development. However, when these two differed, staging was based on breast development only, since thelarche tends to be more closely associated with the production of sex hormones.19

Patients were then classified according to pubertal maturation as prepubertal (TI), pubertal (TII and TIII), or postpubertal (TIV and TV). The age of first menstruation was also collected from all participants and their mothers.

Biochemical analysisSamples for biochemical analysis were collected from all patients with JIA after an 8-hour fast. Inflammatory activity was determined based on CRP levels, determined by turbidimetry (reference values<3.0mg/L) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), assessed using the Westergren method (reference value: 0 to 10mm/h).

Statistical analysisQuantitative variables were described as mean and standard deviation, or median and interquartile range. Categorical variables were summarized as absolute and relative frequencies. Group means were compared using Student's t-test for independent samples. Asymmetrical variables were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U test. Percentages were compared using Pearson's chi-squared tests or Fisher's exact tests. The association between continuous and ordinal variables was analyzed using Pearson's or Spearman's correlation coefficients. Potential confounders were selected based either on the current literature or on the presence of correlations significant at 0.2. These variables were controlled using linear regression models. Significance was set to 5% (p≤0.05), and all analyses were performed in SPSS, version 21.0.

Ethical concernsThis study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital and registered in the Department of Graduate Studies and Research of the Hospital under project number 13-0324.

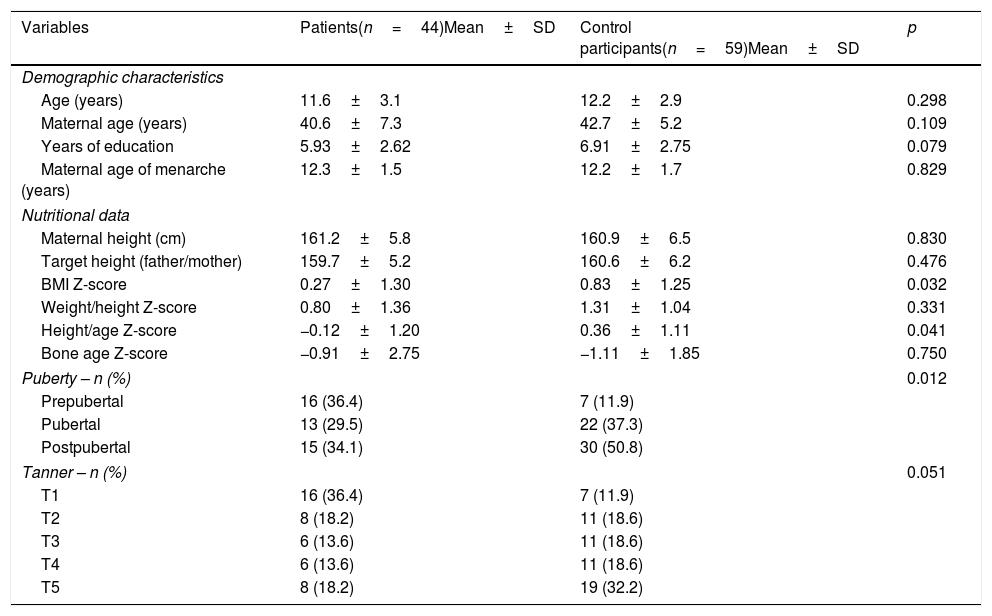

ResultsThe sample included 44 girls with JIA and 59 healthy controls. The groups did not differ in terms of age, maternal age, mean parental height, mother's age of first menstruation, and number of years of education (Table 1).

Sample characteristics.

| Variables | Patients(n=44)Mean±SD | Control participants(n=59)Mean±SD | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | |||

| Age (years) | 11.6±3.1 | 12.2±2.9 | 0.298 |

| Maternal age (years) | 40.6±7.3 | 42.7±5.2 | 0.109 |

| Years of education | 5.93±2.62 | 6.91±2.75 | 0.079 |

| Maternal age of menarche (years) | 12.3±1.5 | 12.2±1.7 | 0.829 |

| Nutritional data | |||

| Maternal height (cm) | 161.2±5.8 | 160.9±6.5 | 0.830 |

| Target height (father/mother) | 159.7±5.2 | 160.6±6.2 | 0.476 |

| BMI Z-score | 0.27±1.30 | 0.83±1.25 | 0.032 |

| Weight/height Z-score | 0.80±1.36 | 1.31±1.04 | 0.331 |

| Height/age Z-score | −0.12±1.20 | 0.36±1.11 | 0.041 |

| Bone age Z-score | −0.91±2.75 | −1.11±1.85 | 0.750 |

| Puberty – n (%) | 0.012 | ||

| Prepubertal | 16 (36.4) | 7 (11.9) | |

| Pubertal | 13 (29.5) | 22 (37.3) | |

| Postpubertal | 15 (34.1) | 30 (50.8) | |

| Tanner – n (%) | 0.051 | ||

| T1 | 16 (36.4) | 7 (11.9) | |

| T2 | 8 (18.2) | 11 (18.6) | |

| T3 | 6 (13.6) | 11 (18.6) | |

| T4 | 6 (13.6) | 11 (18.6) | |

| T5 | 8 (18.2) | 19 (32.2) | |

SD, standard deviation.

Girls with JIA had a lower BMI Z-score than those in the control group. Nine (20.4%) girls in the JIA group and four (6.7%) control participants had a Z-score <−1. No girls in the sample were considered underweight (BMI Z-score <−2) according to WHO standards (Table 1).

With regards to height, nine (20.4%) girls with JIA and five (8.4%) control participants had a height-for-age Z-score of less than −1, while three (6.8%) girls with JIA and one (1.6%) control participant had a Z-score below −2. Between-group differences in height-for-age Z-scores differed only in Tanner stage II (−0.51±1.39 in patients vs. 0.80±1.10 in controls; p=0.034), although in all stages, girls in the control group tended to be taller than those with JIA.

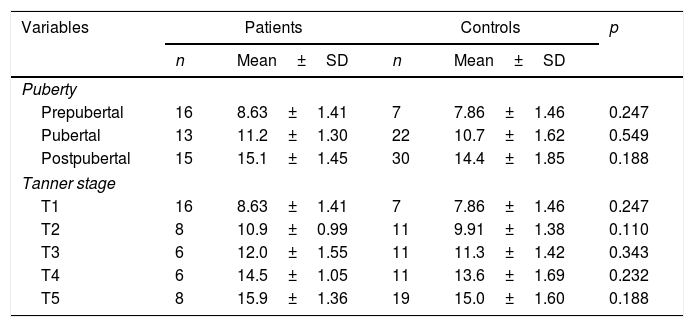

Although the percentage of girls in each Tanner stage did not differ between groups (Table 1), the proportion of prepubertal girls in the JIA group was significantly higher than that observed among control participants (Table 1). However, mean age at each Tanner stage did not differ between groups (Table 2).

Mean age (±standard deviation), in years, of participants in each Tanner and pubertal stage, per group.

| Variables | Patients | Controls | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean±SD | n | Mean±SD | ||

| Puberty | |||||

| Prepubertal | 16 | 8.63±1.41 | 7 | 7.86±1.46 | 0.247 |

| Pubertal | 13 | 11.2±1.30 | 22 | 10.7±1.62 | 0.549 |

| Postpubertal | 15 | 15.1±1.45 | 30 | 14.4±1.85 | 0.188 |

| Tanner stage | |||||

| T1 | 16 | 8.63±1.41 | 7 | 7.86±1.46 | 0.247 |

| T2 | 8 | 10.9±0.99 | 11 | 9.91±1.38 | 0.110 |

| T3 | 6 | 12.0±1.55 | 11 | 11.3±1.42 | 0.343 |

| T4 | 6 | 14.5±1.05 | 11 | 13.6±1.69 | 0.232 |

| T5 | 8 | 15.9±1.36 | 19 | 15.0±1.60 | 0.188 |

SD, standard deviation.

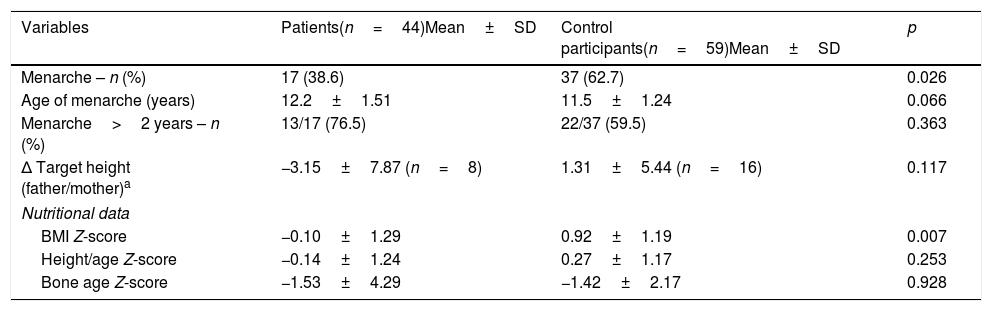

Significant differences were observed in the number of girls experiencing menarche in the JIA and control groups, and although girls with JIA tended to reach menarche at an older age than control participants, this difference was not statistically significant. The comparison of anthropometric characteristics between postmenarcheal girls in each group is shown in Table 3.

Comparison of pre- and postmenarcheal growth parameters between groups.

| Variables | Patients(n=44)Mean±SD | Control participants(n=59)Mean±SD | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Menarche – n (%) | 17 (38.6) | 37 (62.7) | 0.026 |

| Age of menarche (years) | 12.2±1.51 | 11.5±1.24 | 0.066 |

| Menarche>2 years – n (%) | 13/17 (76.5) | 22/37 (59.5) | 0.363 |

| Δ Target height (father/mother)a | −3.15±7.87 (n=8) | 1.31±5.44 (n=16) | 0.117 |

| Nutritional data | |||

| BMI Z-score | −0.10±1.29 | 0.92±1.19 | 0.007 |

| Height/age Z-score | −0.14±1.24 | 0.27±1.17 | 0.253 |

| Bone age Z-score | −1.53±4.29 | −1.42±2.17 | 0.928 |

SD, standard deviation; BMI, body mass index.

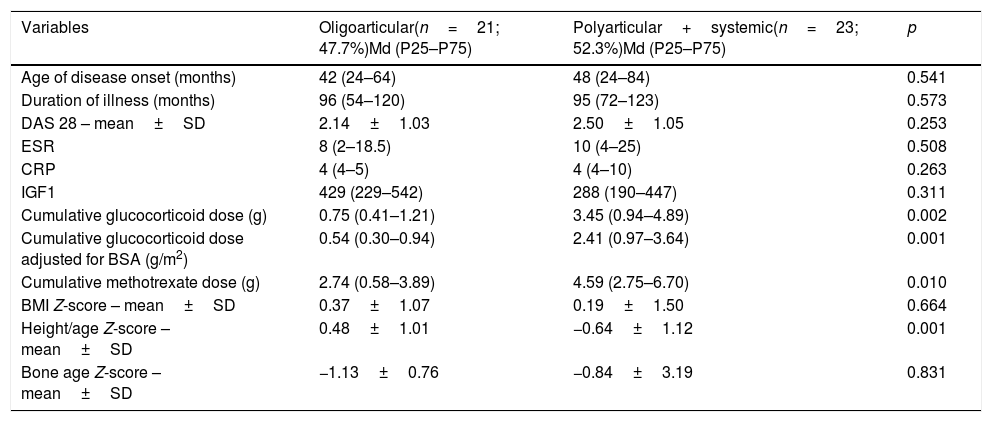

The distribution of participants according to JIA subtypes revealed that 21 (47.7%) girls had oligoarticular disease, while 23 (52.3%) had polyarthritis. The characteristics of each subgroup of patients are described in Table 4. Twenty-three (52.3%) girls with JIA were in remission (DAS 28<2.6), while 10 (22.7%) had mild disease activity (DAS 2.6–3.6). Only one of the nine (20.4%) patients treated with immunobiological therapy had oligoarticular JIA (Table 4).

Comparison between subtypes of juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

| Variables | Oligoarticular(n=21; 47.7%)Md (P25–P75) | Polyarticular+systemic(n=23; 52.3%)Md (P25–P75) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age of disease onset (months) | 42 (24–64) | 48 (24–84) | 0.541 |

| Duration of illness (months) | 96 (54–120) | 95 (72–123) | 0.573 |

| DAS 28 – mean±SD | 2.14±1.03 | 2.50±1.05 | 0.253 |

| ESR | 8 (2–18.5) | 10 (4–25) | 0.508 |

| CRP | 4 (4–5) | 4 (4–10) | 0.263 |

| IGF1 | 429 (229–542) | 288 (190–447) | 0.311 |

| Cumulative glucocorticoid dose (g) | 0.75 (0.41–1.21) | 3.45 (0.94–4.89) | 0.002 |

| Cumulative glucocorticoid dose adjusted for BSA (g/m2) | 0.54 (0.30–0.94) | 2.41 (0.97–3.64) | 0.001 |

| Cumulative methotrexate dose (g) | 2.74 (0.58–3.89) | 4.59 (2.75–6.70) | 0.010 |

| BMI Z-score – mean±SD | 0.37±1.07 | 0.19±1.50 | 0.664 |

| Height/age Z-score – mean±SD | 0.48±1.01 | −0.64±1.12 | 0.001 |

| Bone age Z-score – mean±SD | −1.13±0.76 | −0.84±3.19 | 0.831 |

BMI, body mass index; CRP, C-reactive protein; DAS 28, Disease Activity Score; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; BSA, body surface area, SD, standard deviation.

The cumulative dose of glucocorticoids and methotrexate was inversely associated with height-for-age Z-scores in girls with polyarthritis and systemic JIA. The association between height-for-age Z-scores, polyarticular JIA, and the cumulative glucocorticoid dose remained significant after adjustments in a multivariate model. However, height-for-age Z-scores were not associated with the duration of glucocorticoid treatment (r=0.108; p=0.538) or with bone age Z-scores (r=−0.176; p=0.195).

DiscussionIn this cross-sectional study, a group of girls with JIA was compared to healthy participants with similar characteristics. The authors selected an all-female sample in order to facilitate a uniform assessment of height and puberty, eliminating the variability generated by gender differences in rates of height and pubertal development. The study of patients who had not received glucocorticoids for at least six months allowed us to assess any persistent effects of treatment on height and sexual maturation. Most studies of JIA evaluate patients who are still receiving treatment or whose treatment has been suspended for an unspecified period. By allowing a washout period, this study prevented children with potential for catch-up growth from being classified as having short stature, ensuring this category only included patients with more severe growth impairments.

In this study, although disease activity was adequately controlled in the JIA sample and patients had not received glucocorticoid treatment for at least six months, their BMI and height were still lower than those of control participants. Low height and BMI were associated with polyarticular JIA and a higher cumulative dose of glucocorticoids.

Although all patients had normal weight, girls with JIA were thinner, and 20% of them had BMI Z-scores <−1. Several studies have demonstrated the presence of compromised nutritional status in patients with JIA, especially those with greater disease activity,11,22 polyarticular or extended oligoarticular disease, and with a younger age.23

In 2006, a study performed in a mixed-gender sample of 116 children with JIA found that 16% of participants had BMI values below the 5th percentile, and that this phenomenon was especially pronounced in patients with polyarticular disease.24 In the study in question, 56.9% of the sample had active disease, and those with polyarthritis had a disease duration of 4.5 years (3.0–6.6). In the present study, patients with JIA were shorter than control participants. Eighteen percent of patients with JIA had height Z-scores below −1, and 6% had Z-scores below −2. These values are lower than those observed in the aforementioned investigation. Although this discrepancy may be associated with the inclusion criteria, the authors believe that it is more likely attributable to the increased attention to nutritional issues in the sample and the presence of controlled disease, since 74.9% of participants were in remission or had only mild disease activity.

Although girls with JIA tended to be shorter in stature than control participants across all pubertal stages, this difference was only significant in TII girls, that is, around the beginning of the pubertal growth spurt. With regards to the subtype of JIA, girls with polyarticular disease were shorter in stature than those with oligoarthritis. Interestingly, height was significantly associated with cumulative glucocorticoid dose, but not the duration of treatment. Shorter stature was not associated with age of disease onset or disease activity.

The incidence of short stature in children with JIA has been a growing concern in recent years, as it may lead to psychological problems in adolescence and adulthood. Longitudinal studies of growth in children with JIA have found short stature to be present in 10–20% of patients, depending on the population studied and the method of assessment. The factors associated with short stature in these children are polyarticular or systemic disease, persistent disease activity, and the administration of high doses or prolonged treatment with glucocorticoids.7,11,12,25 Liem et al.12 found that a decrease of more than 2 SD in height-for-age Z-scores was already apparent two years after disease onset in patients with JIA, and Souza et al.,7 who assessed growth rates and their association with IL-6, found that 25.3% of their sample showed decreased growth rates and 60% had elevated IL-6 levels.

In the present study, the prevalence of short stature was 6%, which is lower than that reported in the literature, probably due to the exclusion of patients with recent glucocorticoid exposure. In a longitudinal study of prepubertal children treated with glucocorticoids, Saha et al.26 found reduced growth during the first year of treatment but identified catch-up growth after disease stabilization. The author concluded that improved disease course, lower doses of glucocorticoids, and growth monitoring may contribute to the recovery of growth deficits.

An important limitation of the present study is the cross-sectional design, which does not allow us to analyze the growth velocity calculation across visits and growth impairment over time.

No differences were identified in disease activity or inflammatory markers across different subtypes of JIA. The inclusion criteria may be responsible for these findings, since patients with current or recent glucocorticoid use were excluded. These findings suggest that polyarticular JIA may represent a more severe form of the disease, since its treatment requires higher cumulative doses of glucocorticoids and methotrexate. This conclusion regarding the severity of polyarthritis is in agreement with the current literature.11,12,22,26

Unlawska et al.13 found a prevalence of short stature of 4.6% in a sample of children with JIA. Short stature was associated with polyarticular JIA, disease severity, and a need for higher doses and longer treatment with glucocorticoids.

Adult height is determined by genetic potential and can be estimated based on parental height. Approximately 95% of girls reach adult height within two years of menarche.27 In this study, actual and expected adult height did not differ between groups. Participant and maternal height did not differ between groups, although girls with JIA tended to have lower adult height Z-scores than control participants. The absence of group differences may be partly explained by the small sample.

Based in the mean height obtained in JIA and control groups in this study (−0.14±1.24 vs. 0.27±1.17, respectively) and using an α=0.05 and β=0.10, it was estimated that to confirm the significance of the presented trend between groups (p value <0.05), 80 patients would be necessary in each group.

The control of disease activity before epiphyseal closure, especially in patients with polyarticular disease, may be associated with growth recovery, although at a slower pace. In a study of 24 patients with systemic JIA, Simon et al.11 reported a decrease of −2.7±1.5 in height-for-age Z-scores during glucocorticoid treatment, but identified catch-up growth in 70% of subjects after prednisone treatment was suspended.

Persistent inflammatory activity, low weight, and glucocorticoid treatment may result in low IgF-1 levels, which cause alterations in the secretion of growth hormones and gonadotropins, and result in pubertal delay in children with JIA.4,17,18 The present study's findings regarding pubertal markers were similar to those of El Badri et al.,28 who found that the percentage of prepubertal children in a sample of patients with JIA was higher than that observed in a control group of healthy children. This author found delayed puberty to be present in 16% of the sample, while in the present study, no patients presented with such delays.

In the present investigation, participant groups did not differ as to the mean age of menarche, probably because the patients had little to no disease activity and no glucocorticoid exposure at the time of assessment. These results are in agreement with previous studies which identified no significant differences in the age of menarche between healthy girls and patients with JIA.12,28,29 Some authors have found that in girls with active JIA receiving glucocorticoid treatment, menarche may be delayed by as much as two years.13,29,30

The present findings suggested that even six months after the suspension of glucocorticoid treatment, children with more severe forms of JIA with exposure to higher doses of glucocorticoids are still susceptible to low height and delayed puberty. Although menarche was not delayed, sexual maturation occurred more slowly and gradually in these individuals. Early diagnosis and the control of disease activity are essential in patients with JIA and may prevent the deleterious influence of the disease on growth.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Machado SH, Xavier RM, Lora PS, Gonçalves LM, Trindade LR, Marostica PJ. Height and sexual maturation in girls with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2020;96:100–7.