To evaluate the association between total physical activities, physical activity in free time and nutritional status with self-perceived health in adolescents of both genders.

MethodsThis is a quantitative study that integrates the school-based, cross-sectional epidemiological survey with statewide coverage, whose sample consisted of 6261 adolescents (14–19 years old) selected by random conglomerate sampling. Data were collected using the Global School-based Student Health Survey. The chi-squared test (χ2) and the Poisson regression model with robust variance were used in the data analyses.

ResultsIt was observed that 27.3% of the adolescents had a negative health self-perception, which was higher among girls (33.0% vs. 19.0%, p<0.001). After adjusting for potential confounding factors, it was observed that boys who did not practice physical activity during free time (PR=1.44, 95% CI: 1.15–1.81) and were classified as insufficiently active (PR=1.27, 95% CI: 1.04–1.56), as well as girls who did not practice physical activity during free time (PR=1.15, 95% CI: 1.02–1.29) and were classified as overweight (PR=1.27, 95% CI: 1.01–1.29) had a greater chance of negative health self-perception.

ConclusionBehavioral issues may have different effects on health self-perception when comparing boys with girls. Negative health self-perception was associated with nutritional status in girls and a lower level of physical activity in boys, and the practice of physical activity in the free time was considered a protective factor against a negative health self-perception for adolescents of both genders.

Avaliar a associação entre atividade física total, atividade física no tempo livre e estado nutricional com a autopercepção de saúde em adolescentes de ambos os sexos.

MétodosTrata-se de um estudo com abordagem quantitativa, que integra o levantamento epidemiológico transversal de base escolar e abrangência estadual, cuja amostra foi constituída por 6.261 adolescentes (14 a 19 anos) selecionados por meio de uma estratégia de amostragem aleatória de conglomerados. Os dados foram coletados a partir do questionário Global School-based Student Health Survey. O teste de qui-quadrado (χ2) e o modelo de regressão de Poisson com variância robusta foram usados nas análises dos dados.

ResultadosObservou-se que 27,3% dos adolescentes tinham uma autopercepção de saúde negativa, sendo maior entre as meninas (33,0% vs. 19,0%; p<0,001). Após o ajuste pelos potenciais fatores de confusão, constatou-se que tinham maior chance de ter uma autopercepção de saúde negativa os meninos que não praticavam atividade física no tempo livre (RP=1,44; IC 95%: 1,15-1,81) e que eram classificados como insuficientemente ativos (RP=1,27; IC 95%: 1,04-1,56) e as meninas que não praticavam atividade física no tempo livre (RP=1,15; IC 95%: 1,02-1,29) e que eram classificadas como sobrepesadas (RP=1,27; IC 95%: 1,01-1,29).

ConclusãoQuestões comportamentais podem ter diferentes repercussões na autopercepção de saúde quando comparados os meninos e meninas. A autopercepção de saúde negativa esteve associada ao estado nutricional entre as meninas e a um menor nível de atividade física entre os meninos e a prática de atividade física no tempo livre foi tida como fator de proteção para uma autopercepção de saúde negativa para os adolescentes de ambos os sexos.

Health self-perception (HSP) is an indicator used in surveys and albeit subjective it is strongly related to morbidity, mortality, longevity and health status in different population subgroups.1,2 Specifically in adolescence, HSP comprises continuous body, social, behavioral and mental changes.3 The prevalence of negative HSP in this age range varies from 1.2% to 38%, with girls showing the highest prevalence of negative HSP when compared to boys.4

Epidemiological studies have shown that there is an association between physical activity (PA) and the adoption of other health-related behaviors, with a consequent impact on quality of life5,6 and HSP improvement.6–10 A systematic review including 16 cross-sectional studies with adolescents found that 88% of the studies showed a significant association between PA practice and positive HSP.11 However, the positive effects of PA can be attained in different ways, and one important limitation is that most studies have only evaluated total PA. Therefore, other domains, such as leisure PA and PA types in free time (exercise, sports, dance, and martial arts) have not been investigated.

Nutritional status is another relevant aspect associated with HSP in adolescents, with overweight and obese adolescents showing more negative HSP compared to adolescents with normal weight,12 which has also not been considered by the studies that tested the association between PA and HSP. In addition, another important gap is due to the fact that the associations are not being stratified by gender, which would be necessary, considering that girls show a higher prevalence of negative HSP and greater dissatisfaction with body weight, a fact that is directly related to nutritional status.13,14

The identification of factors (total PA, leisure PA, PA in free time and nutritional status) associated to HSP in adolescents stratified by gender may provide specific subsidies for adolescents, aiding interventions aimed at improving their HSP. Thus, the objective of this study was to evaluate the association of total PA, PA in free time, and nutritional status with HSP in adolescents of both genders.

MethodsThis is a secondary analysis of the data from a cross-sectional, school-based, statewide epidemiological survey called “Physical activity practice and health risk behaviors in high school students in the state of Pernambuco”, carried out between the first (May and June) and second semesters (August, September, October and November) of 2011. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Universidade de Pernambuco (CAAE no. 0158.0.097.000-10/CEP-UPE: 159/10). All the norms of Resolution no. 196/96 of the National Health Council were observed.

The target population, estimated at 373,386 subjects, consisted of high school students aged between 14 and 19 years enrolled in state public schools of Pernambuco. A random sampling procedure with a stratified two-stage cluster sampling design was utilized: (1) school size (fewer than 200 students; 200 to 499 students; and 500 students or more), considering the 17 Regional Education Offices (GREs, Gerências Regionais de Educação) of the state of Pernambuco; and (2) shift (day and night) and grades (1st, 2nd and 3rd grades). Schools and classes were selected using a randomizer program, which provided random numbers.

For sample size calculation the following parameters were used: 95% Confidence Interval; statistical power of 80%; maximum tolerable error of 2 percentage points; design effect (deff)=2; and because it was a study covering the analysis of multiple risk behaviors with different frequencies of occurrence the estimated prevalence was defined as 50%.

The tool used for data collection was an adapted version of the Global School-based Student Health Survey (GSHS). Before starting the data collection, the tool was validated (content and face validity) and submitted to a pilot study, and it showed good consistency in measurements. Most questions showed moderate to high reproducibility indicators, and the coefficients of agreement (kappa index) ranged from 0.62 to 1.00.

The questionnaires were applied in the classroom as a collective interview, without the presence of teachers, and students had the opportunity to clarify any doubts while completing the questionnaires (duration: 30 and 40min). A consent form was used to obtain parental permission for students under the age of 18 to participate in the study. Furthermore, all the students who participated in the study signed the Free and Informed Consent Form (FICF) and indicated their agreement to participate.

The dependent variable of this study was the HSP, in which the adolescents answered the question, “Overall, you consider your health to be...?” with the following options: bad, regular, good and excellent. For the purposes of analysis, the alternatives were categorized in a dichotomous manner: positive (excellent/good) and negative (regular/poor), as shown in similar studies.4

The sociodemographic variables measured in this study were: “age” (14–15 years, 16–17 years, 18–19 years), “occupation” (works or does not work), “area of residence” (urban and rural), and “maternal schooling”, which was stratified as ≤8 years of study and >8 years of study. Regarding the variable “PA Level”, two GSHS questions were considered: (1) “Over the last 7 days, how many days were you physically active for a total of at least 60minutes a day?”; and (2) “During a typical or normal week, how many days are you physically active for a total of at least 60minutes a day?” To estimate the PA level the procedure suggested by Prochaska, Sallis and Longo15 was adopted regarding Questions 1 and 2, using the following formula: (Question 1+Question 2)/2. If the result obtained was a value <5 days, the adolescents were considered insufficiently active; that is, they did not follow the PA recommendations.16 The practice of PA in the free time was determined by the question: “Do you regularly perform some type of physical activity in your free time, such as exercise, sports, dance or martial arts?”, with the dichotomous answer being “yes or no”. The preferred leisure activity was dichotomously categorized into active leisure (exercising, playing sports, biking, or swimming) and passive leisure (watching TV, playing video games, using the computer, talking to friends, playing dominoes or cards).

At the anthropometric assessments all adolescents wore light clothing and remained barefoot. The body mass was evaluated using a Beurer electronic scale with a maximum capacity of 150kg and a precision of 100g. Height was measured using a Wiso portable stadiometer with a 0.5cm precision. The Body Mass Index (BMI) was calculated by dividing the body mass in kilograms by the height in meters squared. The overweight and obesity classification in adolescents considers the cutoff points proposed by the International Obesity Task Force (IOTF) and published by Cole et al. (2000).17

Data tabulation was carried out using the EpiData software (version 3.1). The data were typed in duplicate to verify data entry errors, which, when identified, were corrected based on the original variable values. Data analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 17.0 for Windows. The distribution of absolute and relative frequencies was used in the descriptive analysis.

Bivariate analyses were performed to evaluate the association between the dependent variable and independent variables using Pearson's Chi-squared test (χ2), and the variables that showed a descriptive level (p-value) up to 0.20 were selected for the multiple analysis. The Poisson regression model with robust variance was used in the multiple analysis to estimate the prevalence ratio (PR) and to evaluate the magnitude of the association between the dependent variable and the assessed independent variables. A significance level of 0.05 was set at this stage of modeling.

Multicollinearity analysis was performed assuming Variance Inflation Factor – VIF<5 and a tolerance of <0.20. The quality of data adjustment to the constructed model was tested using the Hosmer–Lemeshow test (p>0.05). Those associations that showed α=5% were considered significant.

ResultsA total of 7195 students from 85 schools in 48 municipalities in Pernambuco were interviewed. After 285 refusals, of which 269 were by the adolescents and 16 by the parents, and the exclusion of 651 questionnaires from students aged under 14 and over 19 years of age the final sample comprised 6259 students, of which 59.7% were females with a mean age of 16.6 years (SD≥1.3 years), who did not work (77.7%), lived in urban areas (74.5%) and had a lower level of maternal schooling (64.7%).

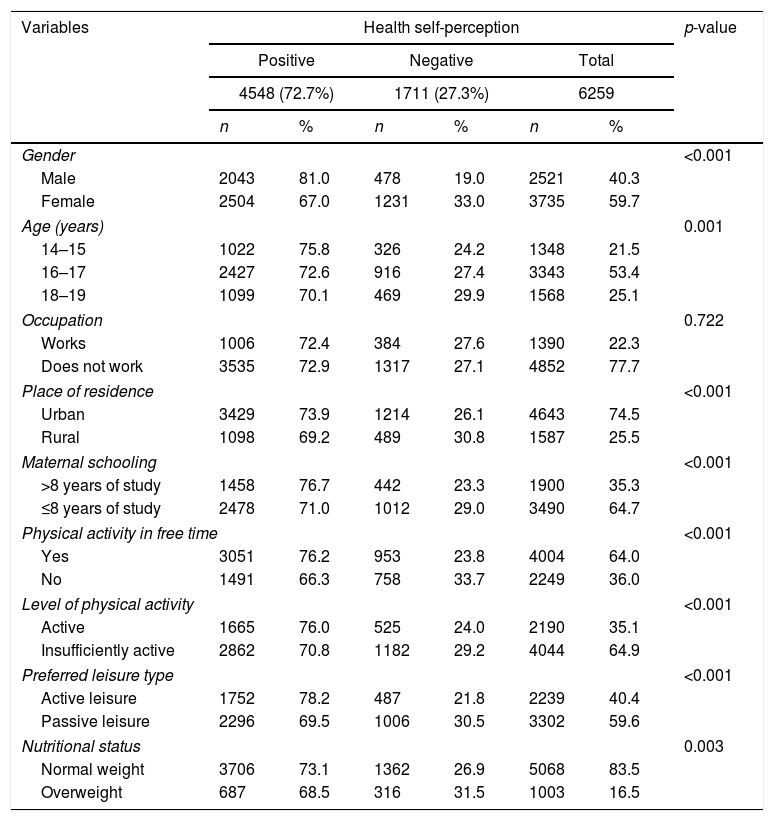

It was observed that 27.3% (95% CI: 26.2–28.5) of the subjects reported a negative HSP, the incidence of which was higher among the girls 33% (95% CI: 31.5–34.5) compared to the boys 19% (95% CI: 17.5–20.6). The proportion of adolescents who negatively evaluated the HSP was more frequent among those who lived in rural areas; those whose mother had a lower level of schooling; those who did not practice physical exercises, were insufficiently active, overweight and preferred more passive leisure activities (Table 1).

Socioeconomic and demographic characteristics and prevalence of nutritional status, preferred leisure type, total physical activity and physical activity in free time of high-school students of the public school system of the state of Pernambuco.

| Variables | Health self-perception | p-value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | Total | |||||

| 4548 (72.7%) | 1711 (27.3%) | 6259 | |||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Gender | <0.001 | ||||||

| Male | 2043 | 81.0 | 478 | 19.0 | 2521 | 40.3 | |

| Female | 2504 | 67.0 | 1231 | 33.0 | 3735 | 59.7 | |

| Age (years) | 0.001 | ||||||

| 14–15 | 1022 | 75.8 | 326 | 24.2 | 1348 | 21.5 | |

| 16–17 | 2427 | 72.6 | 916 | 27.4 | 3343 | 53.4 | |

| 18–19 | 1099 | 70.1 | 469 | 29.9 | 1568 | 25.1 | |

| Occupation | 0.722 | ||||||

| Works | 1006 | 72.4 | 384 | 27.6 | 1390 | 22.3 | |

| Does not work | 3535 | 72.9 | 1317 | 27.1 | 4852 | 77.7 | |

| Place of residence | <0.001 | ||||||

| Urban | 3429 | 73.9 | 1214 | 26.1 | 4643 | 74.5 | |

| Rural | 1098 | 69.2 | 489 | 30.8 | 1587 | 25.5 | |

| Maternal schooling | <0.001 | ||||||

| >8 years of study | 1458 | 76.7 | 442 | 23.3 | 1900 | 35.3 | |

| ≤8 years of study | 2478 | 71.0 | 1012 | 29.0 | 3490 | 64.7 | |

| Physical activity in free time | <0.001 | ||||||

| Yes | 3051 | 76.2 | 953 | 23.8 | 4004 | 64.0 | |

| No | 1491 | 66.3 | 758 | 33.7 | 2249 | 36.0 | |

| Level of physical activity | <0.001 | ||||||

| Active | 1665 | 76.0 | 525 | 24.0 | 2190 | 35.1 | |

| Insufficiently active | 2862 | 70.8 | 1182 | 29.2 | 4044 | 64.9 | |

| Preferred leisure type | <0.001 | ||||||

| Active leisure | 1752 | 78.2 | 487 | 21.8 | 2239 | 40.4 | |

| Passive leisure | 2296 | 69.5 | 1006 | 30.5 | 3302 | 59.6 | |

| Nutritional status | 0.003 | ||||||

| Normal weight | 3706 | 73.1 | 1362 | 26.9 | 5068 | 83.5 | |

| Overweight | 687 | 68.5 | 316 | 31.5 | 1003 | 16.5 | |

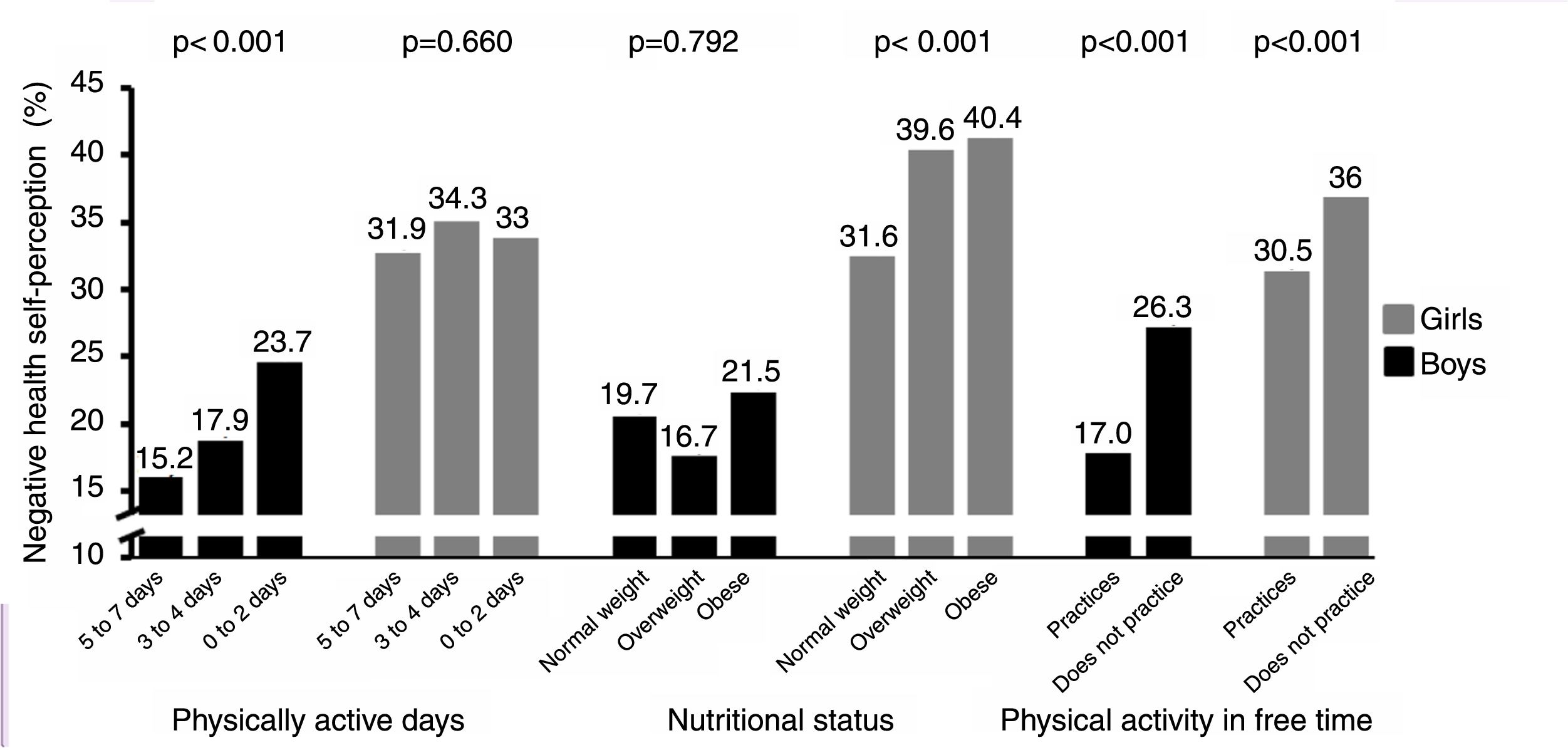

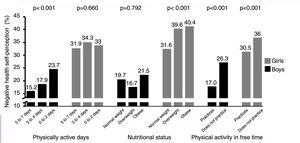

A higher prevalence of negative HSP was observed in boys who practiced PA for two or fewer days (p<0.001) and among girls who were classified as overweight or obese (p<0.001). Regarding PA in free time, a higher prevalence of negative HSP was observed both in boys and girls who did not practice PA in their free time (p<0.001) (Fig. 1).

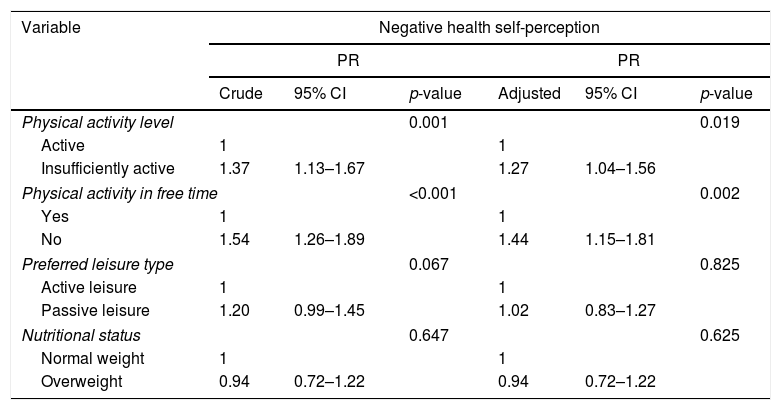

The need for stratification by gender was verified after testing the interaction. Thus, it was observed that boys who did not practice PA in their free time (PR=1.44, 95% CI: 1.15–1.81) and who were classified as insufficiently active (PR=1.27, 95% CI: 1.04–1.56) were more likely to have a negative HSP even after adjusting for potential confounding factors (Table 2).

Association between negative health self-perception and physical activity level, physical activity in free time and nutritional status in boys.

| Variable | Negative health self-perception | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PR | PR | |||||

| Crude | 95% CI | p-value | Adjusted | 95% CI | p-value | |

| Physical activity level | 0.001 | 0.019 | ||||

| Active | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Insufficiently active | 1.37 | 1.13–1.67 | 1.27 | 1.04–1.56 | ||

| Physical activity in free time | <0.001 | 0.002 | ||||

| Yes | 1 | 1 | ||||

| No | 1.54 | 1.26–1.89 | 1.44 | 1.15–1.81 | ||

| Preferred leisure type | 0.067 | 0.825 | ||||

| Active leisure | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Passive leisure | 1.20 | 0.99–1.45 | 1.02 | 0.83–1.27 | ||

| Nutritional status | 0.647 | 0.625 | ||||

| Normal weight | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Overweight | 0.94 | 0.72–1.22 | 0.94 | 0.72–1.22 | ||

Adjusted for age, maternal schooling, place of residence and other independent variables.

Active leisure: practicing sports, exercising, swimming, and biking.

Passive leisure: playing dominoes or cards, watching TV, playing video games, using the computer and chatting with friends.

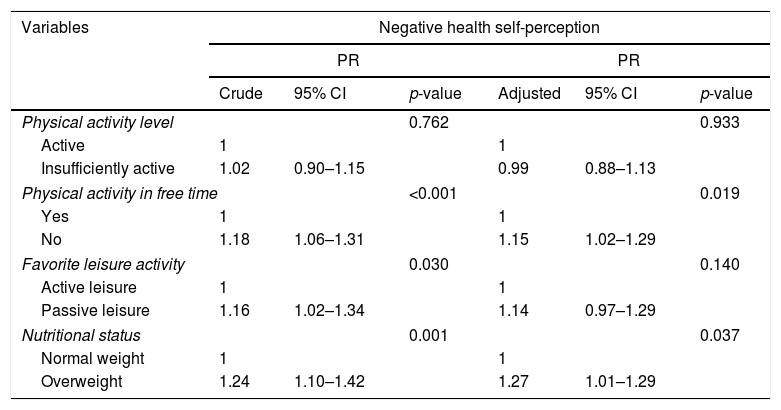

Regarding the girls, it was observed after the adjustment that those who did not practice PA in their free time (PR=1.15, 95% CI: 1.02–1.29) and were classified as overweight (PR=1.27; 95% CI: 1.01–1.29) were more likely to have a negative HSP (Table 3).

Association between negative health self-perception and physical activity level, physical activity in free time and nutritional status in girls.

| Variables | Negative health self-perception | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PR | PR | |||||

| Crude | 95% CI | p-value | Adjusted | 95% CI | p-value | |

| Physical activity level | 0.762 | 0.933 | ||||

| Active | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Insufficiently active | 1.02 | 0.90–1.15 | 0.99 | 0.88–1.13 | ||

| Physical activity in free time | <0.001 | 0.019 | ||||

| Yes | 1 | 1 | ||||

| No | 1.18 | 1.06–1.31 | 1.15 | 1.02–1.29 | ||

| Favorite leisure activity | 0.030 | 0.140 | ||||

| Active leisure | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Passive leisure | 1.16 | 1.02–1.34 | 1.14 | 0.97–1.29 | ||

| Nutritional status | 0.001 | 0.037 | ||||

| Normal weight | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Overweight | 1.24 | 1.10–1.42 | 1.27 | 1.01–1.29 | ||

Adjusted for age, maternal education, place of residence and other independent variables.

Active leisure: practicing sports, exercising, swimming, and biking.

Passive leisure: playing dominoes or cards, watching TV, playing video games, using the computer and chatting with friends.

The main objective of this study was to evaluate the association of total PA, PA in free time, and nutritional status with HSP in adolescents. The main results were: (i) a high prevalence of negative HSP was observed, particularly among girls; (ii) adolescents living in rural areas, whose mothers had a lower level of schooling, who did not practice PA in their free time, were insufficiently active, were overweight, and preferred more passive leisure activities had a higher negative HSP; (iii) a negative HSP was associated with nutritional status in girls and a lower level of PA in boys; and (iv) adolescents of both genders who did not practice PA during their free time were more likely to have a negative HSP.

The prevalence of negative HSP observed in the present study was 27.3% higher than that found in other national3,7,18–21 and international8,9,22 studies with adolescents. In Brazil, national surveys are not available for this population subgroup; however, state and municipal studies show a prevalence of negative HSP in adolescents ranging from 11.5%21 to 25.7%.20 The differences found in Brazilian studies may be due to different socioeconomic, cultural and environmental characteristics, as well as access to and quality of health services and care offered to the population.23

As in most studies,7,8,18–21 girls have a higher prevalence of negative HSP compared to boys. In agreement with this result, a study carried out to assess the temporal tendency of HSP in adolescents from 32 countries in Europe and North America observed that girls report a higher negative HSP than boys in all the assessed countries.24 This difference in HSP between genders may be related to cultural issues related to a belief that girls undergo more routine examinations and have more doctor's appointments, all of which increases the chance of early diagnosis of a disease.25 Moreover, girls are more aware, sensitive and better informed about health, thus perceiving it in a broader manner.8,25 Therefore, compared to boys they consider a larger set of factors when making overall health classifications, such as psychological factors and small subjective health complaints.25 Additionally, studies have highlighted greater body dissatisfaction among girls, perhaps due to an exacerbated media pressure on the female body, and such dissatisfaction may have repercussions on the HSP.13,14

The present study showed that sociodemographic factors, such as living in rural areas and having a lower level of maternal schooling were associated with a negative HSP. Similar results were found in other national studies7,18,21; they demonstrate the importance of social and economic issues among the aspects that can influence HSP in adolescents. Specifically in Brazil it can be observed that vulnerabilities are not evenly distributed within the society–space ratio, especially in rural areas, and they are mainly perceivable by the scarcity of choices of leisure, culture and sports practice, as well as a lack of public communal areas, which in turn affects the quality of life of adolescents, especially regarding health-related aspects.26 Moreover, in a study carried out with adolescents living in rural areas in Brazil it was possible to observe that health conceptions revealed the inequalities and difficulties regarding their access to health care,27 which may partially explain the results that were found.

Regarding the social issues, a higher purchasing power is a determining factor for greater access to other forms of leisure activities, education, housing, and health services, and thus it can act as a mediator of the HSP level.23,24 Moreover, parents with higher levels of schooling tend to better understand what being healthy means and what their children need, which leads them to have better health levels.28

Another interesting point found in the present study is that behavioral issues may have different effects on HSP when comparing adolescents of both genders. It is noteworthy that boys and girls have different understandings regarding their health status.25 In this sense, it was observed that only among boys a negative HSP is associated with the level of total PA. It is believed that the practice of PA in adolescence has a positive effect on self-image and the reduction of anxiety and depression symptoms; therefore, those effects combined are capable of generating a more positive HSP.11

It was observed that the nutritional status among girls, which may be related to esthetics, was associated with HSP, as those who were classified as overweight were more likely to have a negative HSP, an association not found in boys. In a study carried out with the same target audience of the present investigation it was emphasized that there is a tendency for boys to feel good about their body image regardless of the nutritional status, unlike what happens with girls, who tend to overestimate their weight and show a greater dissatisfaction with their body image.13

In this sense, it can be observed that anthropometric issues such as overweight interfere with the HSP mainly in girls. The results of the study by Heshmat et al.12 showed a significant association between girls with higher BMI and a negative HSP; the same result was not found among boys. Adolescents with excess weight are more vulnerable to social discrimination, and particularly girls are more concerned with body fat and more likely to consider themselves fat, when compared to boys. The latter, in turn, are less interested in weight loss and more concerned with masculinity-related issues, such as increasing muscle mass.29 Those differences in body image between both genders may partially explain the association between anthropometric issues in girls and negative HSP.

It was observed that not practicing PA in the free time was associated with a negative HSP in both genders. In this sense, a study with Swedish adolescents showed that the ones who did not practice sports and showed a low level of PA had a higher prevalence of negative HSP.8 One of the possible explanations for this association is focused on the beneficial effect of PA on monoamines in the brain, which affect neurotransmission by attenuating anxiety, tension and stress,30 or on the production of endorphins and reduction of pain, thus increasing the sense of well-being, which has clear consequences on mental health.11 These findings are consistent with those from other studies, such as the one carried out in the city of João Pessoa, in the state of Paraíba, Brazil, which found that adolescents who did not reach the recommendations for PA practice and those who were overweight were three times more likely to have negative HSP when compared to their sufficiently active peers and those with normal weight.7 However, the results in that study were not stratified by gender and the participation of adolescents in other domains and types of PA was not observed.

Certain limitations of the present study should be considered. While we acknowledge that direct methods would bring more accurate information, the levels of total PA and PA practiced in the free time were obtained by indirect measurement. Moreover, despite the use of a representative sample the generalization of the collected data to all adolescents should be treated with caution, since the study was restricted to students from the state public school system. Additionally, there is also the possibility of reverse causality as an inherent characteristic of cross-sectional studies.

Among the strengths of the present research we can highlight the representativeness of the student population of public high schools in the state of Pernambuco, the use of a previously tested questionnaire that had a moderate-to-high reproducibility level, and the control of variables affecting the analysis.

It was concluded that a negative HSP was associated with nutritional status in girls and with a lower level of PA in boys. Furthermore, the practice of PA in the free time was considered a protective factor for a negative HSP in adolescents of both genders.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

We would like to thank the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (Capes), Fundação de Amparo à Ciência e Tecnologia do Estado de Pernambuco (Facepe), Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) and the Secretariat of Education of the state of Pernambuco.

Please cite this article as: Silva AO, Diniz PR, Santos ME, Ritti-Dias RM, Farah BQ, Tassitano RM, et al. Health self-perception and its association with physical activity and nutritional status in adolescents. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2019;95:458–65.

Study conducted at Universidade de Pernambuco (UPE), Recife, PE, Brazil.