To determine the prevalence of benign febrile seizures of childhood and describe the clinical and epidemiological profile of this population.

MethodsThis was a population-based, cross-sectional study, carried out in the city of Barra do Bugres, MT, Brazil, from August 2012 to August 2013. Data were collected in two phases. In the first phase, a questionnaire that was previously validated in another Brazilian study was used to identify suspected cases of seizures. In the second phase, a neurological evaluation was performed to confirm diagnosis.

ResultsThe prevalence was 6.4/1000 inhabitants (95% CI: 3.8–10.1). There was no difference between genders. Simple febrile seizures were found in 88.8% of cases. A family history of febrile seizures in first-degree relatives and history of epilepsy was present in 33.3% and 11.1% of patients, respectively.

ConclusionsThe prevalence of febrile seizures in Midwestern Brazil was lower than that found in other Brazilian regions, probably due to the inclusion only of febrile seizures with motor manifestations and differences in socioeconomic factors among the evaluated areas.

Estabelecer a prevalência das crises febris e descrever o perfil clínico e epidemiológico dessa população.

MétodosEstudo transversal de base populacional realizado na cidade de Barra do Bugres (MT), no período de agosto de 2012 a agosto de 2013. Os dados foram coletados em duas etapas. Na primeira fase utilizamos um questionário validado previamente em outro estudo brasileiro, para identificação de casos suspeitos de crises epilépticas. Na segunda etapa realizamos a avaliação neuroclínica para confirmação diagnóstica.

ResultadosA prevalência de crise febril foi de 6,4/1000 habitantes (IC95% 3,8; 10,1). Não houve diferença entre os sexos. As crises febris simples foram encontradas em 88,8% dos casos. A história familiar de crise febril e epilepsia em parentes de 1° grau esteve presente em 33,3% e 11,1% dos pacientes, respectivamente.

ConclusõesA prevalência da crise febril na região centro-oeste foi menor do que a encontrada em outras regiões brasileiras, provavelmente relacionado à inclusão apenas das crises febris com manifestações motoras e as diferenças de fatores socioeconômicos entre as regiões pesquisadas.

Febrile seizures are the most common seizures in children younger than 5 years, affecting 2–5% of the pediatric population1; they are considered to be benign and self-limited,2 and are classified as simple and complex.1 Upper airway viral infections are the most common triggering factors.3,4 The risk of subsequently developing epilepsy is 6.9%5; although they have an excellent prognosis, they bring anxiety to parents and family members.6

The clinical signs of febrile seizures are not different among populations, but the clinical and demographic characteristics are not identical in the different parts of the world,7 thus justifying the necessity of the present study. There is no Brazilian study that has described the clinical and epidemiological characteristics of patients with febrile seizures.

This study aimed to determine the prevalence and describe the clinical and epidemiological characteristics of patients with febrile seizures.

MethodsStudy site and assessed populationThe study was conducted in the municipality of Barra do Bugres, state of Mato Grosso, Brazil, from August 2012 to August 2013. The estimated population in 2013 was 33,022 inhabitants,8 with 3445 inhabitants aged between 0 and 5 years and 11 months, of whom 1775 were males and 1670 females.8 Approximately 60% of the population is of African descent. In the municipality, 77% of the households have sewerage and 55% have water supply services. The Human Development Index of the municipality is 0.693 and the per capita income, based the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of 2012 was US$ 6740.00.8 The municipality has six healthcare teams working for the Family Health Program (FHP) and forty-six healthcare workers attending to 75% of the population; the population that is not assisted by the FHP receives health care in a Basic Health Unit located downtown. The fact that the municipality has good FHP coverage and that the program works regularly facilitated this study.

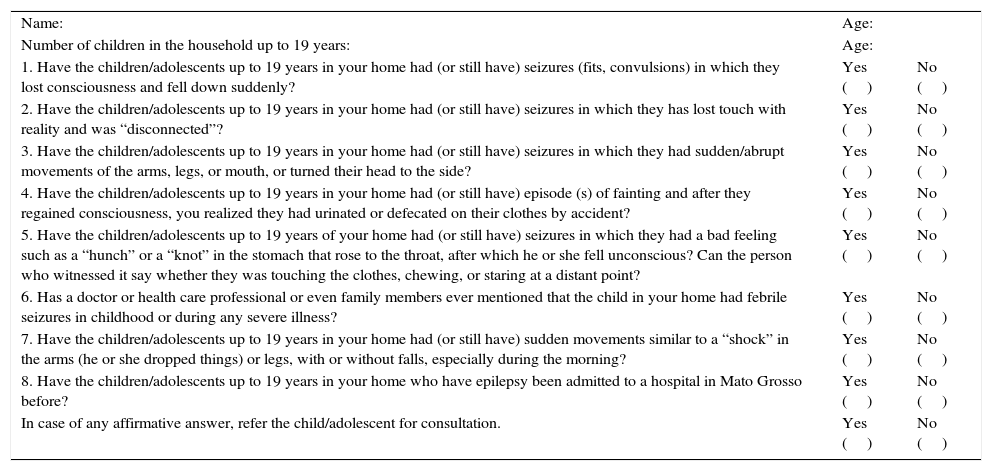

Study phasesThis was a cross-sectional, population-based study, performed in two phases. In the first phase, the healthcare workers performed an active search at the households, seeking suspected cases of seizures. A questionnaire with eight questions was used (Table 1). The questions were modified from the guidelines of the World Health Organization and are similar to the questions used in epidemiological studies conducted in Ecuador,9 and were previously validated in a Brazilian study with a sensitivity of 95.8% and specificity of 97.8%.10 This screening questionnaire was also used in a prevalence study of epilepsy in childhood in the state of São Paulo.11 The healthcare workers were previously trained and received explanations on seizures/epilepsy and how to apply the questionnaire. The cases in which there was at least one affirmative response to the eight questions were referred to the second phase of the evaluation (diagnostic confirmation), when the clinical history was obtained and the neurological examination was performed.

Screening questionnaire.10

| Name: | Age: | |

| Number of children in the household up to 19 years: | Age: | |

| 1. Have the children/adolescents up to 19 years in your home had (or still have) seizures (fits, convulsions) in which they lost consciousness and fell down suddenly? | Yes () | No () |

| 2. Have the children/adolescents up to 19 years in your home had (or still have) seizures in which they has lost touch with reality and was “disconnected”? | Yes () | No () |

| 3. Have the children/adolescents up to 19 years in your home had (or still have) seizures in which they had sudden/abrupt movements of the arms, legs, or mouth, or turned their head to the side? | Yes () | No () |

| 4. Have the children/adolescents up to 19 years in your home had (or still have) episode (s) of fainting and after they regained consciousness, you realized they had urinated or defecated on their clothes by accident? | Yes () | No () |

| 5. Have the children/adolescents up to 19 years of your home had (or still have) seizures in which they had a bad feeling such as a “hunch” or a “knot” in the stomach that rose to the throat, after which he or she fell unconscious? Can the person who witnessed it say whether they was touching the clothes, chewing, or staring at a distant point? | Yes () | No () |

| 6. Has a doctor or health care professional or even family members ever mentioned that the child in your home had febrile seizures in childhood or during any severe illness? | Yes () | No () |

| 7. Have the children/adolescents up to 19 years in your home had (or still have) sudden movements similar to a “shock” in the arms (he or she dropped things) or legs, with or without falls, especially during the morning? | Yes () | No () |

| 8. Have the children/adolescents up to 19 years in your home who have epilepsy been admitted to a hospital in Mato Grosso before? | Yes () | No () |

| In case of any affirmative answer, refer the child/adolescent for consultation. | Yes () | No () |

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hospital Geral Universitário (Registered under n.128 CEP/UNIC–protocol n. 2011-128).

Inclusion and exclusion criteriaChildren with a history of at least one episode of febrile seizure residing in Barra do Bugres and aged 0–5 years were included in the study. Patients whose condition did not fit the definition of febrile seizures were excluded. Febrile seizures without motor symptoms were not considered, due the difficulty in ascertaining whether they were really epileptic seizures according to the description of the family members.

DefinitionsFebrile seizures were defined as seizures occurring in children older than 1 month and younger than 5 years associated with febrile illness. This definition excluded seizures that occurred in the presence of central nervous system infection or cases with a history of epileptic seizures in the neonatal period, unprovoked seizures, and acute symptomatic seizures.12 Febrile seizures can be classified as simple or complex; simple seizures are primarily generalized, lasting less than 15min with no recurrence within 24h, whereas complex seizures are focal, last longer than 15min, and show recurrence within 24h.1

Data processing and statistical analysisThe data collected during the interview in pre-coded questionnaires were processed in a personal computer, typed in duplicate to reduce typos, in an electronic database using Excel (Microsoft 2003. Microsoft Excel [computer software]. Redmond, Washington, USA). When inconsistent data were found, they were verified in the original questionnaire and the necessary corrections were performed. Data were analyzed descriptively, and 95% confidence intervals were built for their respective prevalence in the inferential analysis. This technique was used because the comparison measurement scale was categorical or non-quantitative.

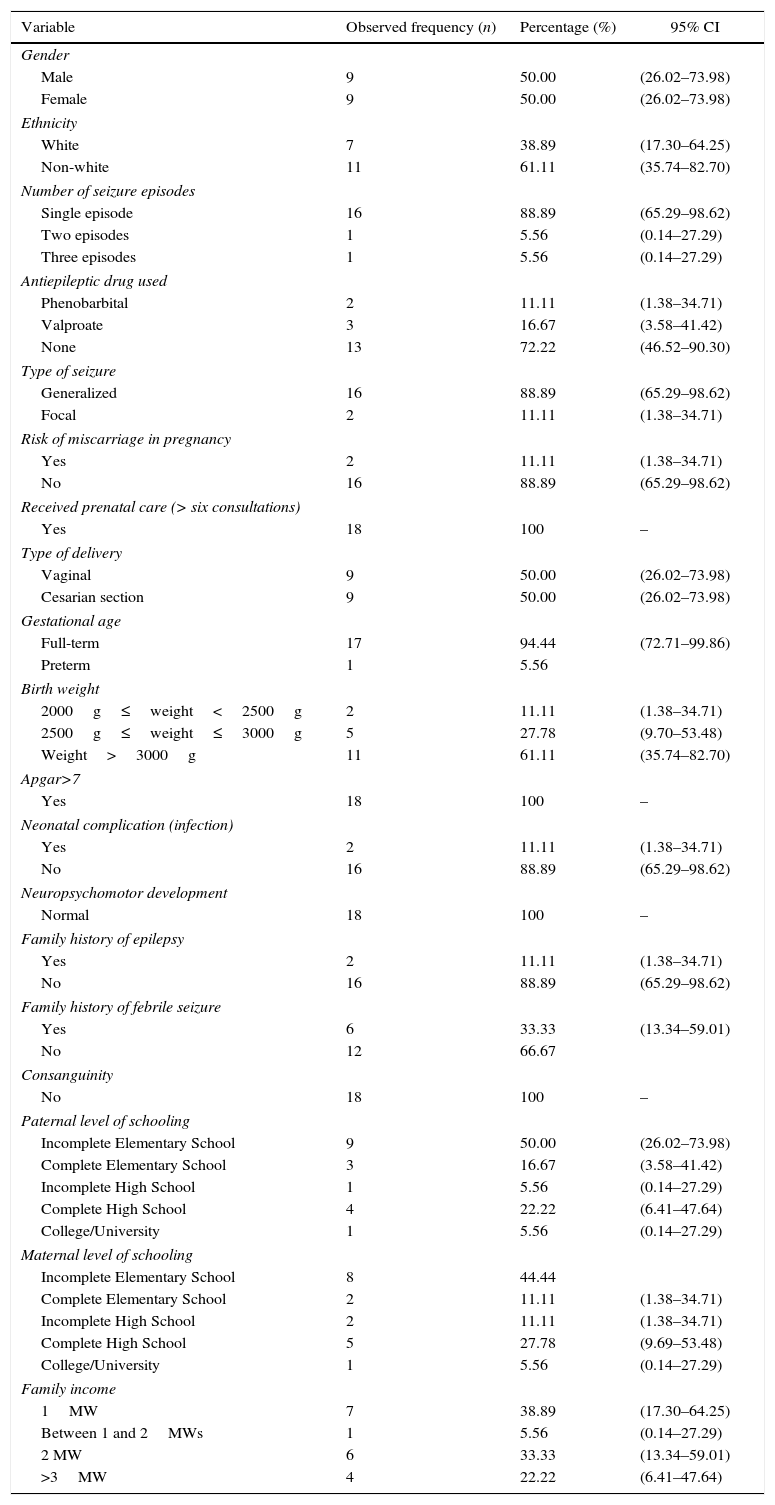

ResultsThe municipality of Barra do Bugres has a population of 3445 inhabitants at the age range of 0–5 years and 11 months; a total of 2811 inhabitants (81.6%) were screened. The losses in the first phase of the study occurred because it was not possible to find residents in the households in more than one visit by the healthcare workers. The prevalence of febrile seizures in this sample was 6.40/1000 inhabitants (95% CI: 3.8–10.10). The age at the first seizure ranged from 1 month to 60 months (mean of 19.38 months). Clinical and sociodemographic variables are shown in Table 2.

Observed frequency distribution, percentage, and 95% CI of 18 patients with febrile seizures according to clinical and sociodemographic variables. Barra do Bugres, MT, Brazil, 2014.

| Variable | Observed frequency (n) | Percentage (%) | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 9 | 50.00 | (26.02–73.98) |

| Female | 9 | 50.00 | (26.02–73.98) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| White | 7 | 38.89 | (17.30–64.25) |

| Non-white | 11 | 61.11 | (35.74–82.70) |

| Number of seizure episodes | |||

| Single episode | 16 | 88.89 | (65.29–98.62) |

| Two episodes | 1 | 5.56 | (0.14–27.29) |

| Three episodes | 1 | 5.56 | (0.14–27.29) |

| Antiepileptic drug used | |||

| Phenobarbital | 2 | 11.11 | (1.38–34.71) |

| Valproate | 3 | 16.67 | (3.58–41.42) |

| None | 13 | 72.22 | (46.52–90.30) |

| Type of seizure | |||

| Generalized | 16 | 88.89 | (65.29–98.62) |

| Focal | 2 | 11.11 | (1.38–34.71) |

| Risk of miscarriage in pregnancy | |||

| Yes | 2 | 11.11 | (1.38–34.71) |

| No | 16 | 88.89 | (65.29–98.62) |

| Received prenatal care (> six consultations) | |||

| Yes | 18 | 100 | – |

| Type of delivery | |||

| Vaginal | 9 | 50.00 | (26.02–73.98) |

| Cesarian section | 9 | 50.00 | (26.02–73.98) |

| Gestational age | |||

| Full-term | 17 | 94.44 | (72.71–99.86) |

| Preterm | 1 | 5.56 | |

| Birth weight | |||

| 2000g≤weight<2500g | 2 | 11.11 | (1.38–34.71) |

| 2500g≤weight≤3000g | 5 | 27.78 | (9.70–53.48) |

| Weight>3000g | 11 | 61.11 | (35.74–82.70) |

| Apgar>7 | |||

| Yes | 18 | 100 | – |

| Neonatal complication (infection) | |||

| Yes | 2 | 11.11 | (1.38–34.71) |

| No | 16 | 88.89 | (65.29–98.62) |

| Neuropsychomotor development | |||

| Normal | 18 | 100 | – |

| Family history of epilepsy | |||

| Yes | 2 | 11.11 | (1.38–34.71) |

| No | 16 | 88.89 | (65.29–98.62) |

| Family history of febrile seizure | |||

| Yes | 6 | 33.33 | (13.34–59.01) |

| No | 12 | 66.67 | |

| Consanguinity | |||

| No | 18 | 100 | – |

| Paternal level of schooling | |||

| Incomplete Elementary School | 9 | 50.00 | (26.02–73.98) |

| Complete Elementary School | 3 | 16.67 | (3.58–41.42) |

| Incomplete High School | 1 | 5.56 | (0.14–27.29) |

| Complete High School | 4 | 22.22 | (6.41–47.64) |

| College/University | 1 | 5.56 | (0.14–27.29) |

| Maternal level of schooling | |||

| Incomplete Elementary School | 8 | 44.44 | |

| Complete Elementary School | 2 | 11.11 | (1.38–34.71) |

| Incomplete High School | 2 | 11.11 | (1.38–34.71) |

| Complete High School | 5 | 27.78 | (9.69–53.48) |

| College/University | 1 | 5.56 | (0.14–27.29) |

| Family income | |||

| 1MW | 7 | 38.89 | (17.30–64.25) |

| Between 1 and 2MWs | 1 | 5.56 | (0.14–27.29) |

| 2 MW | 6 | 33.33 | (13.34–59.01) |

| >3MW | 4 | 22.22 | (6.41–47.64) |

MW, Brazilian minimum wage; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

The prevalence of febrile seizures in this sample was 6.4/1000 inhabitants; in the literature, it ranges from 3.5/100013 to 17/1000.14 Two Brazilian studies assessed the prevalence of febrile seizures, showing a rate of 13.9/1000 in São Paulo, SP, Brazil and 16/1000 in Pelotas, RS, Brazil.11,15 In the assessed area, it was observed that the prevalence was lower than that found in the South and Southeast regions of Brazil. These differences in prevalence rates may be justified by different methodologies used for patient recruitment, socioeconomic factors, and particularities of the populations from each region studied. In the present study, active search in households was used for patient recruitment, with 18.4% of losses in this age group.

When comparing with the study conducted in Pelotas, RS, Brazil, which used a birth cohort, the losses consisted of 26.2% individuals that could not be assessed, thereby indicating a larger population analysis in the present study. The study conducted in São Paulo, SP, Brazil used a convenience sample to assess individuals treated at Complexo Einstein in the Paraisópolis community, thus creating a bias that could justify a higher prevalence in that study.

Socioeconomic differences may also explain the lower prevalence found in Mato Grosso; when comparing the basic sanitation in the municipality (sewerage and water supply services), per capita income, and Human Development Index of the municipality with other studied regions, better socioeconomic indicators were observed in Barra do Bugres.

Although over 60% of the population is of African descent, the region has been colonized by populations originating from different regions of Brazil. Thus, the population is very particular, reflecting the miscegenation observed in this country. This is different from other Brazilian regions, where the population is more homogeneous, indicating that Barra do Bugres bears more resemblance to the general Brazilian population profile. In this study, only febrile seizures with motor manifestations were included. This, together with the abovementioned factors, may explain the lower prevalence found in the present study.

Studies have shown a variation in simple febrile seizure prevalence ranging from 55.2% to 85.6%16,17; in the present study, this proportion was 88.8%, similar to that reported in Tunisia, Turkey, Cameroon, India, China, Iran, and England.16–23 Status epilepticus secondary to febrile seizure was not observed in the present study, unlike the one conducted in Cameroon, which identified it in 10% of cases.24

When analyzing the frequency of febrile seizures in relation to gender, no difference was observed, similar to the research by Pavlovic et al.25 differing from some studies in which the authors described a higher frequency in the male gender,7,16,19,26 whereas only Sillanpää et al. found a predominance in the female gender.27

The family history of febrile seizures and epilepsy in first-degree relatives was found respectively in 33.3% and 11.1% of cases. Studies have shown a variation from 14.7% to 39.3%16,17,19,20,22–24,28 in relation to family history of febrile seizures and from 2.7% to 12.71%16,17,20,24 regarding epilepsy.

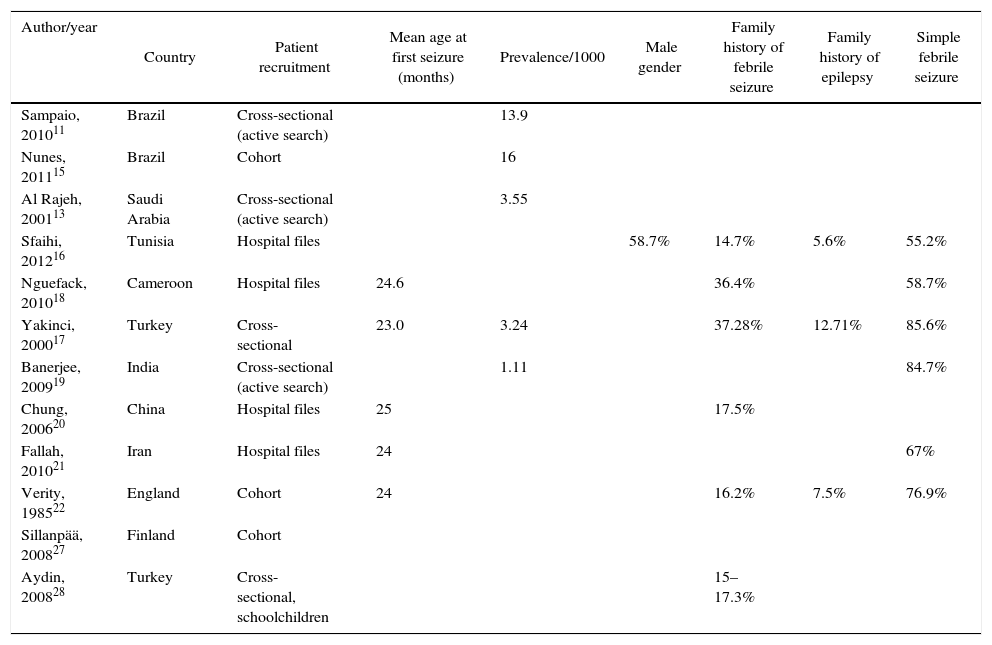

Family income was up to two minimum wages in 77.7% of cases. Studies have shown that the prevalence of febrile seizures is not associated with social class and parental level of schooling.22,23Table 3 shows a summary of the main variables in articles published to date, demonstrating the lack of data regarding the pre- and perinatal periods and the heterogeneity of the studied variables, which hinders data comparison and the development of meta-analyses related to the subject.

Characteristics assessed in the main studies on febrile seizures.

| Author/year | Country | Patient recruitment | Mean age at first seizure (months) | Prevalence/1000 | Male gender | Family history of febrile seizure | Family history of epilepsy | Simple febrile seizure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sampaio, 201011 | Brazil | Cross-sectional (active search) | 13.9 | |||||

| Nunes, 201115 | Brazil | Cohort | 16 | |||||

| Al Rajeh, 200113 | Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional (active search) | 3.55 | |||||

| Sfaihi, 201216 | Tunisia | Hospital files | 58.7% | 14.7% | 5.6% | 55.2% | ||

| Nguefack, 201018 | Cameroon | Hospital files | 24.6 | 36.4% | 58.7% | |||

| Yakinci, 200017 | Turkey | Cross-sectional | 23.0 | 3.24 | 37.28% | 12.71% | 85.6% | |

| Banerjee, 200919 | India | Cross-sectional (active search) | 1.11 | 84.7% | ||||

| Chung, 200620 | China | Hospital files | 25 | 17.5% | ||||

| Fallah, 201021 | Iran | Hospital files | 24 | 67% | ||||

| Verity, 198522 | England | Cohort | 24 | 16.2% | 7.5% | 76.9% | ||

| Sillanpää, 200827 | Finland | Cohort | ||||||

| Aydin, 200828 | Turkey | Cross-sectional, schoolchildren | 15–17.3% |

It can be concluded that the prevalence of febrile seizures in the Midwest region was lower than that found in other Brazilian regions, probably due to the inclusion only of febrile seizures with motor manifestations and to the socioeconomic differences among the assessed regions.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The authors would like to thank the Health Secretariat of the municipality of Barra do Bugres, the Family Health Program, and the technical-administrative team of Centro de Saúde do Maracanã who spared no efforts to conduct this research.

Please cite this article as: Dalbem JS, Siqueira HH, Espinosa MM, Alvarenga RP. Febrile seizures: a population-based study. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2015;91:529–34.