An early and accurate recognition of success in treating obesity may increase the compliance of obese children and their families to intervention programs. This observational, prospective study aimed to evaluate the ability and the time to detect a significant reduction of adiposity estimated by body mass index (BMI), percentage of fat mass (%FM), and fat mass index (FMI) during weight management in prepubertal obese children.

MethodsIn a cohort of 60 prepubertal obese children aged 3–9 years included in an outpatient weight management program, BMI, %FM, and FMI were monitored monthly; the last two measurements were assessed using air displacement plethysmography. The outcome measures were the reduction of >5% of each indicator and the time to achieve it.

ResultsThe rate of detection of the outcome was 33.3% (95% CI: 25.9–41.6) using BMI, significantly lower (p<0.001) than either 63.3% using %FM (95% CI: 50.6–74.8) or 70.0% (95% CI: 57.5–80.1) using FMI. The median time to detect the outcome was 71 days using FMI, shorter than 88 days using %FM, and similar to 70 days using BMI. The agreement between the outcome detected by FMI and by %FM was high (kappa 0.701), but very low between the success detected by BMI and either FMI (kappa 0.231) or %FM (kappa 0.125).

ConclusionsFMI achieved the best combination of ability and swiftness to identify reduction of adiposity during monitoring of weight management in prepubertal obese children.

O reconhecimento precoce e preciso do sucesso no tratamento da obesidade pode aumentar a adesão de crianças obesas e suas famílias a programas de intervenção. Este estudo observacional prospectivo visa avaliar a capacidade e o tempo de detecção de uma redução significativa na adiposidade estimada pelo índice de massa corporal (IMC), no percentual de massa gorda (% MG) e no índice de massa gorda (IMG) durante o controle de peso em crianças obesas pré-púberes.

MétodosEm uma coorte de 60 crianças obesas pré-púberes com idades entre 3 e 9 anos, incluídas em um programa ambulatorial de controle de peso, o IMC, o % MG e o IMG foram monitorados mensalmente, e as duas últimas medições avaliadas foram feitas utilizando pletismografia por deslocamento de ar. As medições resultantes foram redução de>5% de cada indicador e atingir o tempo para tanto.

ResultadosA taxa de detecção do resultado foi de 33,3% (IC de 95% 25,9-41,6) utilizando IMC, significativamente menor (p<0,001) que 63,3% utilizando % MG (IC de 95% 50,6-74,8) ou 70,0% (IC de 95% 57,5-80,1) utilizando IMG. O tempo médio para detectar o resultado foi de 71 dias utilizando o IMG, menos que 88 dias utilizando %MG e semelhante a 70 dias utilizando o IMC. A concordância entre o resultado detectado pelo IMG e pelo % MG foi elevada (kappa 0,701), porém muito baixa entre o sucesso detectado pelo IMC e pelo IMG (kappa 0,231) ou %MG (kappa 0,125).

ConclusõesO IMG atingiu a melhor combinação de capacidade e precocidade para identificar redução na adiposidade durante o monitoramento do controle de peso em crianças obesas pré-púberes.

While definition of obesity is based on excessive adiposity,1 the best measurement for degree of body fatness remains controversial.2 The heterogeneity of outcome measures used to assess the effectiveness of interventions in childhood obesity has made it difficult to compare results.3

In large-scale population surveys and clinical or public health screening, body mass index (BMI) is commonly used as a surrogate measure for body fat content1,4; it is typically adjusted for age and sex, and expressed as centiles or Z-scores.5 While BMI is a good index of cardio-metabolic risk, it may be not a good index of adiposity.6 In a recent meta-analysis, BMI was found to have high specificity but low sensitivity for detection of excess adiposity in children.7 BMI may be particularly biased as a proxy for longitudinal adiposity assessment in children since strong correlations exist between BMI and components of weight other than body fat mass (FM), such as lean mass and bone mass.6,8 In addition, it is not certain that a child tracking along a given BMI centile will also maintain this position in the distribution of body fat.9 Consequently, BMI may not be recommended to monitor adiposity changes in children.9–11

The percentage of fat mass (%FM), defined as fat mass/body weight×100, has been commonly used as a more reliable index of body-size-adjusted adiposity.1 Being a proportion, with FM included both in numerator and denominator (as component of body mass), %FM may be difficult to interpret either as a measure of adiposity2 or as an indicator of its changes.9 Adjusting FM to an unrelated measure of body size, such as a linear measure (i.e., height), has been suggested as a strategy to improve interpretation.12 The FM index (FMI), defined as FM (kg) divided by height squared (m2), has been proposed to better discriminate adiposity than %FM,2 and reference values for children have been published.8,13

Air displacement plethysmography (ADP) is a reliable two-compartment model to evaluate changes in adiposity in children by measuring FM and %FM.14 It has been validated in children aged 7–10 years.15

Performance of BMI, %FM, and FMI in detecting adiposity changes has been assessed and compared in growing children,9–11,16 but data are scarce on the performance of these indicators in obese children participating in weight management programs.17 It is postulated that earlier positive reinforcement will contribute to the success of weight management programs.

This study evaluated the performance of BMI, %FM, and FMI in monitoring adiposity changes during weight management intervention in prepubertal obese children, in order to identify which indicator has the highest early detection rate of adiposity reduction. The authors hypothesize that FMI is a better early indicator of adiposity reduction than %FM and BMI.

MethodsThis prospective, observational study included a convenience cohort of 60 prepubertal obese children (34 females) consecutively referred during a period of one year to a tertiary pediatric hospital outpatient clinic for confirmed childhood obesity. Obesity was defined as BMI over the 95th centile for age and sex.18,19 Puberty was excluded based on Tanner stages.20 The median age at recruitment was 7.6 years (3–9 years), with no statistical difference between sexes. The study was approved by the institutional ethics committee.

A customized weight management program was applied to all patients, in compliance with the outpatient clinic protocol, including oral and written prescriptions for: (1) a planned diet or daily eating plan with balanced macronutrients, in proportions consistent with Dietary Reference Intake recommendations for age, especially foods low in energy density, such as those with high fiber or water content21,22 and (2) exercising more than one hour per day at least three times per week.23 Prescriptions and scheduled assessments were provided by the same pediatrician (CD) and the same dietician (AA).

These children were assessed in the Nutrition Lab for anthropometry and body composition measurement at admission, and scheduled for monthly follow-up. Individuals not complying with this scheduled were not included in the analysis. No additional assessment was undertaken for the purposes of this study. Body mass, measured by the Bod Pod device (Life Measurements – Concorde, CA, USA), was considered as body weight. Height was measured using the Seca 240 Wall-Mounted Stadiometer (3M, A&D Medical, S, USA) by the same trained observer (ED) according to the recommended technique,24 and the average of three measurements was recorded for analysis. The World Health Organization's AnthroPlus software (http://who-anthroplus.software.informer.com/) was used for calculation of BMI and BMI Z-scores.

Body composition was measured by the same observer (MPGD) using the ADP method (Bod Pod; Life Measurements – Concorde, CA, United States). According to the manufacturer's instructions, measurements were obtained with the subjects wearing tight-fitting swimsuit and swim cap only. This method measures body mass, FM, and fat-free mass (FFM) expressed in kg, with precision of 0.1kg. The %FM was calculated by the equipment, assuming the density of fat to be 0.9007kg/L, and pre-determined age- and gender-specific densities of FFM.14 The FMI was computed as FM (kg) divided by height squared (m2).

The primary outcome was the detection rate of 5% reduction in adiposity by each indicator (BMI, %FM, and FMI), a convenience threshold. Time (days) to achieve detection of 5% reduction in adiposity was a secondary outcome. Precision of the detection rate is given by the 95% confidence interval (CI), calculated using OpenEpi (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention – Atlanta, GA, USA), and proportions were compared using chi-squared or Fisher's exact test, as indicated. Time to achieve detection for the whole sample and for each indicator was described with Kaplan–Meyer survival curves. Time to achieve detection of 5% reduction in adiposity, in cases in which it occurred, was described with median and extremes for each indicator of adiposity, and compared using the Kruskal–Wallis test. Cohen's kappa statistic (k) was used to measure the agreement between cases detected by each adiposity indicator. Statistics were calculated using SPSS 22.0 (IBM Corp. – Armonk, NY, USA).

ResultsThe median (extremes) time of follow-up of recruited children was 105 (35–561) days.

Body composition assessed before the intervention and at the end of the follow-up is presented in Table 1.

Body composition assessments before and after the weight management intervention.

| Intervention | Females | Males | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI Z-score mean (SD) | Before | 3.27 (0.89) | 4.46 (1.65) | 3.78 (1.39) |

| After | 2.91 (0.82) | 4.15 (1.91) | 3.45 (1.52) | |

| %FM median (min–max) | Before | 37.9 (28.0–47.7) | 39.3 (26.8–52.9) | 38.3 (26.8–52.9) |

| After | 34.8 (23.4–45.1) | 36.5 (24.7–52.5) | 35.3 (23.4–52.5) | |

| FMI median (min–max) | Before | 8.7 (6.2–13.2) | 9.8 (6.0–19.7) | 9.0 (6.0–17.9) |

| After | 7.4 (5.1–12.8) | 8.9 (5.1–17.8) | 8.0 (5.1–17.8) |

BMI, body mass index; %FM, percent of fat mass; FMI, fat mass index.

Detection rates for 5% reduction in adiposity were 33.3% (95% CI: 25.9–41.6) using BMI, 63.3% (95% CI: 50.6–74.8) using %FM, and 70.0% (95% CI: 57.5–80.1) using FMI. Detection rate was significantly lower using BMI (p<0.001), but did not differ between use of %FM or FMI (p=0.657).

The detection rate using any of the indicators was not significantly different between sexes.

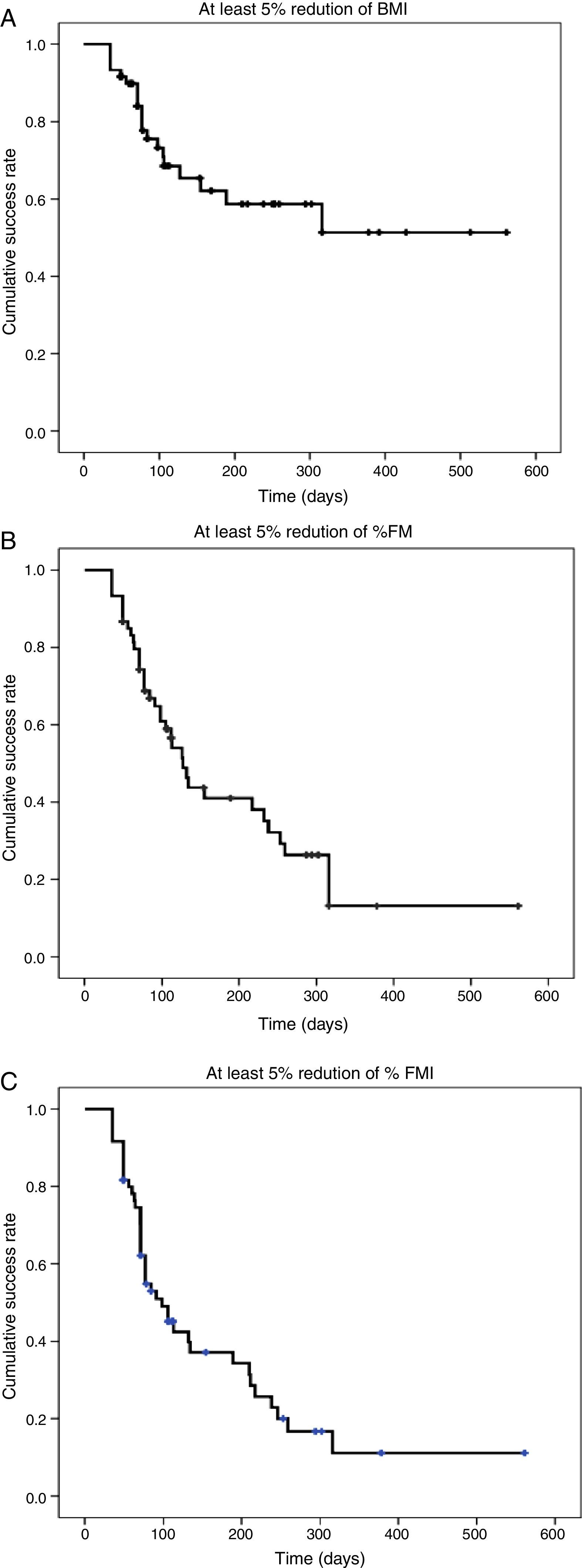

Time to achieve detection using each indicator for the whole sample, expressed with Kaplan–Meyer survival curves, is presented in Fig. 1. The detection of 5% reduction in adiposity in 50% of the cohort was achieved at 98 days (95% CI: 70.0–126.0) using FMI, and at 127 days (95% CI: 102.9–151.1) using %FM; less than 50% of the cohort achieved the threshold for detection of reduction in adiposity using BMI (Fig. 1).

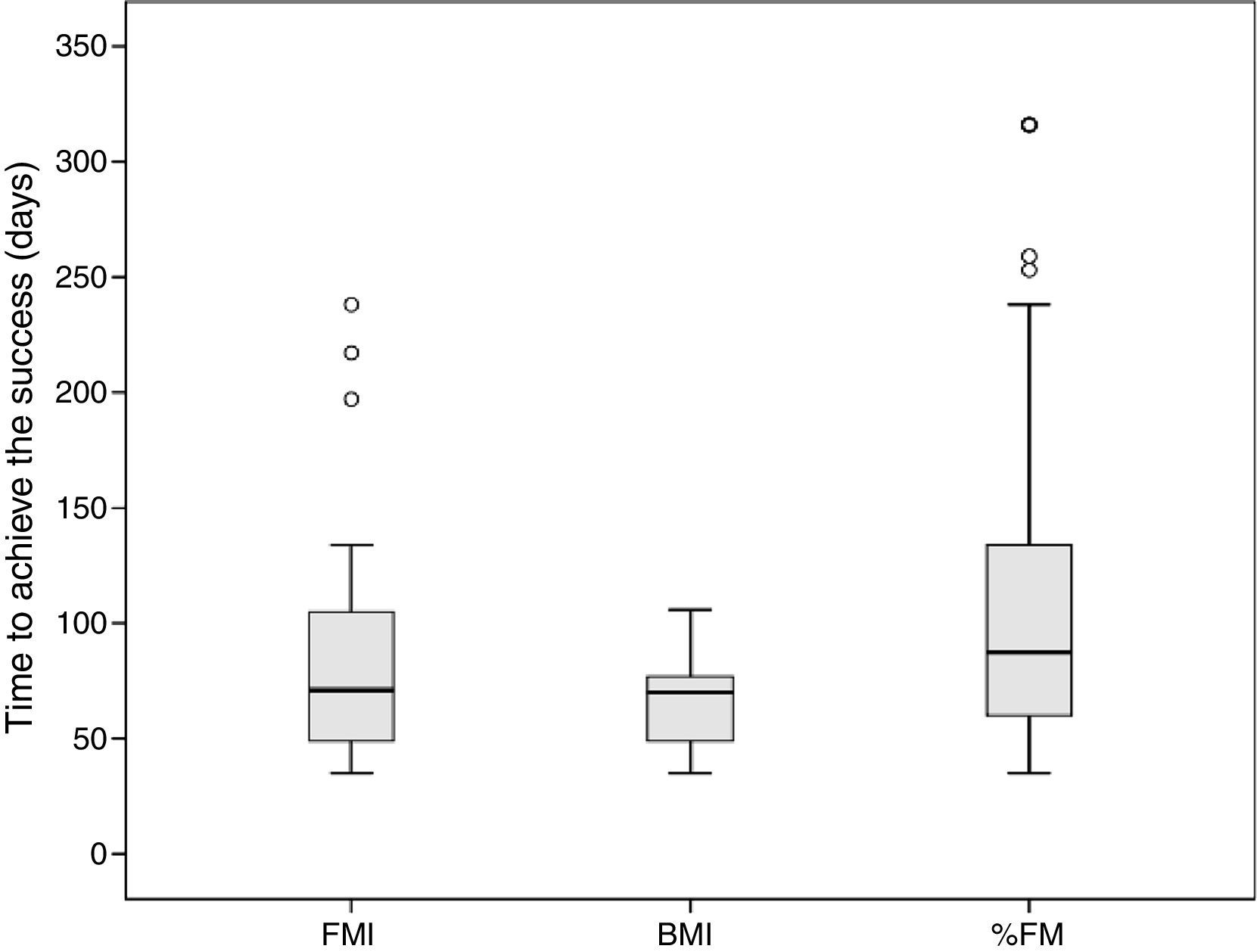

The median time to detect 5% reduction in adiposity was 71 (35–238) days using FMI, similar to 70 (35–316) days using BMI (p=0.223), and with weak evidence (p=0.067) of being shorter than 88 (35–316) days using %FM (Fig. 2). The median time to detect 5% reduction in adiposity using BMI was significantly shorter than using %FM (p=0.009). In the cohort of males, no significant differences in the time to detect 5% reduction in adiposity were found between the indicators. In the cohort of females, the time to detect 5% reduction in adiposity was significantly shorter using BMI than %FM (p=0.018). At recruitment, the median age of females in whom 5% reduction in adiposity was detected using BMI was 7.8 years vs. 6.0 years for those in whom success was not detected (Mann–Whitney test, p=0.083); no difference in age was found in males.

The median (extremes) time to achieve the success (reduction ≥5% in each indicator) was 71 (35–238) days using FMI, 70 (35–316) days using BMI, and 88 (35–316) days using %FM. The median time to detect success using BMI was significantly shorter than using %FM (Kruskal–Wallis test; p=0.009).

FMI, fat mass index; BMI, body mass index; %FM, percent of fat mass.

The agreement between the detection of 5% reduction in adiposity by FMI and by %FM was high (k=0.701), but very low between the success detected by either FMI or %FM and BMI (k=0.231 and k=0.125, respectively).

DiscussionIn this observational, prospective cohort of prepubertal obese children included in a weight management program, the detection rate of early decrease in adiposity using the BMI estimation was low (33.3%). However, both FMI and %FM were found to have greater ability to detect early adiposity changes (70% and 63.3%, respectively).

Time to detect reduction in adiposity was shorter for FMI and BMI than for %FM. The best combination of ability and swiftness to detect a significant reduction in the adiposity estimate was achieved by FMI. The %FM had a good ability to detect adiposity change, but it took longer than FMI or BMI. Although BMI detected adiposity change earlier, it had a lower detection rate than the other indicators.

This study aimed to compare the performance of three indicators of adiposity detecting differences over time, and not to assess the effectiveness of the management of obesity. Additionally, the accuracy of the studied adiposity indicators in obese children has already been verified using diverse gold-standard methods7,9 and is beyond the aim of this study.

To assess adiposity change as an outcome of weight management intervention in growing children, the indicators of outcome can be measured as raw units, percentages, Z-scores, or centiles; however, the suitability of the different measures is not known.10 To the best of the authors’ knowledge, no Z-scores or centiles are available for ADP-measured FM for this targeted age group. Therefore, a 5% reduction in the magnitude of the studied indicators (BMI, %FM, and FMI) was considered a convenient cut-off for short-term indicators of success.

In childhood, the BMI has different performances depending on whether the purpose is to detect excess of adiposity, change of adiposity in the general population, or change of adiposity in obese children participating in weight management programs. In a systematic review and meta-analysis, BMI was found to have low sensitivity and failed to identify over one-quarter of children with excess %FM.7 In some cohort studies, BMI was reported to have low performance for detecting changes of adiposity in childhood.9–11,16 Nonetheless, BMI charts were found to provide a reasonably accurate indication of body fat changes measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry in obese children aged 8–15 years participating in a weight management program.17

Parallel variations of FM and body weight may reduce the performance of %FM to detect changes in adiposity9 and impact its ability to monitor response to obesity treatment. FMI, associating an accurate estimate of FM with measured height, overcomes this interference, potentially improving its performance to detect short-term changes in adiposity in prepubertal children aged 3–9 years, in whom height velocity is relatively constant and lower than in other age groups.20 Limitations of %FM and advantages of FMI have already been addressed in both the diagnosis of obesity2,8,13 and the identification of adiposity changes in children.9

Interventions for treating obesity in children have included dietary intervention and promotion of physical activity.25 Low levels of patient and family compliance have influenced the success of some of these interventions.26 Early positive reinforcement may increase the compliance of obese children and their families. Using either FMI or BMI to monitor treatment detects adiposity reduction around two weeks earlier than using %FM; however, BMI failed to detect reduction of adiposity in more than half the children detected by FMI. Although FMI and %FM detect reduction of adiposity at similar rate, the increased time of detection using %FM delays the opportunity for positive reinforcement by approximately two weeks and, thus, may interfere with intervention compliance and effectiveness.26

Limitations of this study should be acknowledged. Firstly, recruitment was based on the clinical diagnosis of obesity and not on accurate indicators of excessive adiposity, such as indices based on FM measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry.7 The ADP method has been validated in children aged 7–10 years,15 but not yet in younger children, making it unreliable for ascertainment of the recruitment of obese children. Instead, BMI18 was used for recruitment, as it is the most widely used clinical criterion to screen obesity in outpatient children.7 Conceptually, this might have introduced a selection bias for including children with less adiposity, but the high BMI Z-scores found in the assessment before the intervention (Table 1) makes this bias unlikely. Secondly, the difference between genders found in the time taken to detect success may be due to the different size of the two small subsamples, as only prepubertal children were included and the detection rates for the outcome measures were similar. Nevertheless, a potential interference of the adiposity rebound in females cannot be excluded, considering the weak evidence that females in whom success was detected using BMI are older than those who did not achieve success.

To conclude, the best combination of ability and swiftness to detect a 5% reduction in adiposity for monitoring weight management in prepubertal obese children was achieved using FMI. The present data suggest that outpatient clinics specialized in treatment of childhood obesity equipped with methods able to accurately detect early changes in FM are able to provide earlier positive reinforcement.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The authors are grateful to Kayla M. Bridges, MS, RD, CSP, CNSC, St. John Providence Children's Hospital, Detroit, Michigan, United States, for the critical review of the manuscript.

Please cite this article as: Pereira-da-Silva L, Pitta-Grós Dias M, Dionísio E, Virella D, Alves M, Diamantino C, et al. Fat mass index performs best in monitoring management of obesity in prepubertal children. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2016;92:421–6.

Study linked to the Nutrition Lab, Hospital de Dona Estefânia, Centro Hospitalar de Lisboa Central, Lisbon, Portugal.