To determine the prevalence of life support limitation (LSL) in patients who died after at least 24h of a pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) stay, parent participation and to describe how this type of care is delivered.

MethodsRetrospective cohort study in a tertiary PICU at a university hospital in Brazil. All patients aged 1 month to 18 years who died were eligible for inclusion. The exclusion criteria were those brain death and death within 24h of admission.

Results53 patients were included in the study. The prevalence of a LSL report was 45.3%. Out of 24 patients with a report of LSL on their medical records only 1 did not have a do-not-resuscitate order. Half of the patients with a report of LSL had life support withdrawn. The length of their PICU stay, age, presence of parents at the time of death, and severity on admission, calculated by the Pediatric Index of Mortality 2, were higher in patients with a report of LSL. Compared with other historical cohorts, there was a clear increase in the prevalence of LSL and, most importantly, a change in how limitations are carried out, with a high prevalence of parental participation and an increase in withdrawal of life support.

ConclusionsLSLs were associated with older and more severely ill patients, with a high prevalence of family participation in this process. The historical comparison showed an increase in LSL and in the withdrawal of life support.

Medicine has evolved gradually and steadily with important technological advances over the past 50 years, such as with mechanical ventilation and renal replacement therapy. Treatment in intensive care units (ICUs) has made it possible to prolong the life of a series of patients with irreversible diseases and a poor prognosis who would otherwise inevitably die.1,2 However, these treatments can be accompanied by great suffering for both patients and family members. In Brazil, the Brazilian Society of Pediatrics follows the recommendations of the World Health Organization (WHO) for the treatment of patients under palliative care.3 The good medical practice recommends that patients in the ICU should die peacefully, with comfort and dignity, which is often achieved by using some form of life support limitation (LSL).4

Since the 2000s, 90% of ICU deaths in adult patients in North America have been preceded by some form of LSL.5 Studies investigating modes of death in pediatric ICUs (PICUs) in Europe and the United States have reported a prevalence of LSL ranging from 30 to 60%,6,7 while a study that investigated deaths occurring in 2002 at 3 PICUs located in the same city in Brazil reported that only 31.6% of patients had some form of LSL.2

Brazilian studies have shown a relatively modest growth in the prevalence of LSL. When present, this practice basically consists of do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders. In our country, there is a very low prevalence of withholding and withdrawal of life support from dying patients.8–10

The aim of the present study was to determine the prevalence of LSL and to describe how this type of care is delivered in a PICU in Brazil, including a historical comparison with previous studies conducted in the same region over the past 30 years.

MethodsThis retrospective study was conducted in a tertiary PICU in southern Brazil and was approved by the research ethics committee of the institution (approval number 08966518.4.0000.5336). The study setting was a 12-bed medical-surgical PICU affiliated with a medical school that provides care to patients aged 28 days to 18 years old. It has a mean of 400 admissions per year, with a mortality rate of 4–6%. Although this is a private hospital, access to care is also provided through the Brazilian Unified Health System, and approximately 70% of patients are admitted through this system. Patients are admitted through the hospital’s emergency department, ward, and surgical unit, in addition to patient transfers from other centers. The hospital also has a medical residency program in Pediatrics and Pediatric Intensive Care Medicine, in addition to the master’s and doctoral programs in Pediatrics and Child Health.

All deaths occurring in the PICU from March 1, 2015, to February 28, 2019, were included in the study. Exclusion criteria were diagnosis of brain death and length of PICU stay <24h. The reason for this was that medical care decided upon after the diagnosis of brain death is not considered as LSL, since there is national legislation that directs the procedures after this diagnosis. We also consider that the length of stay in the PICU <24h is not enough to allow the team to properly decide on LSL. Data on death were collected by a review of the death record files of the unit.

Data on the following variables were collected for all patients included in the study: age, sex, weight, type of patient (medical or surgical), Pediatric Index of Mortality 2 (PIM2) score,11 organ failure on admission, origin (emergency department, ward, surgical unit, or transfer from another hospital), complex chronic condition according to Feudtner et al.,12 mechanical ventilation, length of hospital stay, and length of PICU stay.

Information on the mode of death was collected from the patients’ medical records, and included reports of LSL, palliative care, DNR order, cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), psychological counseling, palliative extubation, lack of nutritional support in the 24h prior to death, presence of parents at the time of death, and behavior of vasoactive and sedative drugs in the 24h prior to death.

Psychological counseling was defined as at least one psychologist’s record on the patient’s electronic medical record. We had a team of psychologists monitored for all patients admitted to the PICU. Psychological counseling was offered to family members and also to children, when possible. Lack of nutritional support in the 24h prior to death was defined as no enteral feeding, excluding parenteral nutrition and glucose maintenance solution. The patients’ medical records were searched for reports of LSL, DNR order, and terminal palliative care. As a retrospective study, it is impossible to access the professionals who treated patients at the time of death, so LSL was defined as any report of such an occurrence by any member of the multidisciplinary team in charge of the patient at any time after admission to the PICU. DNR order and palliative care were defined as the exact report of these terms in any section of the patient’s medical record (list of problems, evaluation and/or management, and plans). Family participation was defined as a medical record of family participation at any time after the definition of LSL. The start dates of all measures and monitoring efforts were collected.

The behavior of vasoactive and sedative/analgesic drugs in the 24h prior to death was defined as a change, for more than 1h, in the dose of any continuous infusion drug: norepinephrine, epinephrine, dobutamine, milrinone, dopamine, vasopressin or morphine, midazolam, ketamine, clonidine, fentanyl, and dexmedetomidine. For analysis, we considered patients who maintained or increased the dose of any of these drugs.

Variables related to the forms of LSL were classified as follows: received CPR, DNR order, withholding of life support, and withdrawal of life support.13 For further analysis, patients were divided into 2 groups of patients with and without a report of LSL on their medical record, and the demographic, clinical, and death-related management variables were compared.

For statistical analysis, categorical variables were expressed as a number and percentage analyzed by Pearson’s chi–square test or Fisher’s exact test. Continuous variables were expressed as median and interquartile range (IQR) and analyzed by the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test A p-value <0.05 was considered significant. Data analysis was performed in SPSS, version 17.0 (IBM SPSS Statistic, Armonk, NY).

Finally, we compared the prevalence rates of LSL, CPR, and brain death with of those with other similar historical cohorts in the studies conducted by Kipper et al. (1988; 1998; and 1999−2000)8 and Lago et al.2 To determine an evolution over time, patients with a diagnosis of brain death were included only in this final analysis.

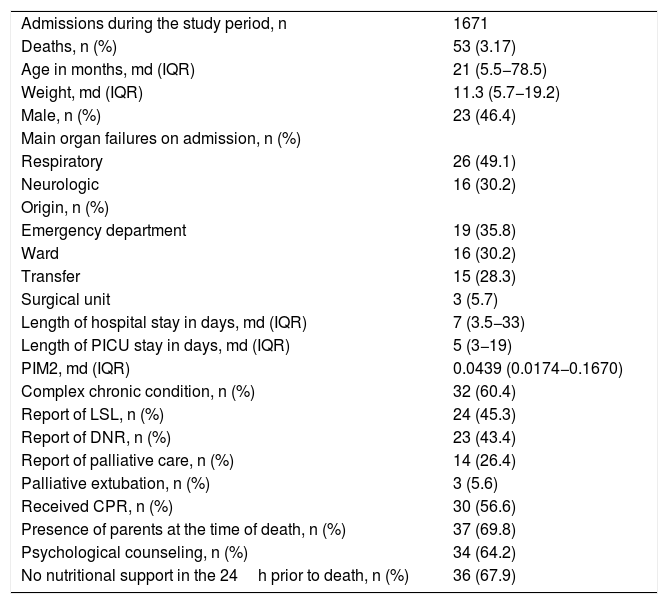

ResultsOf 1671 patients admitted during the study period, 72 died. Of these dead, 53 were eligible for inclusion. Among the 19 excluded patients, 11 died before 24h of PICU admission (of these, 6 stayed <8h in the PICU) and 8 had a confirmed diagnosis of brain death. Table 1 shows the clinical and demographic characteristics and death-related management strategies in the total sample.

Clinical and demographic characteristics and death-related management in the study sample.

| Admissions during the study period, n | 1671 |

| Deaths, n (%) | 53 (3.17) |

| Age in months, md (IQR) | 21 (5.5−78.5) |

| Weight, md (IQR) | 11.3 (5.7−19.2) |

| Male, n (%) | 23 (46.4) |

| Main organ failures on admission, n (%) | |

| Respiratory | 26 (49.1) |

| Neurologic | 16 (30.2) |

| Origin, n (%) | |

| Emergency department | 19 (35.8) |

| Ward | 16 (30.2) |

| Transfer | 15 (28.3) |

| Surgical unit | 3 (5.7) |

| Length of hospital stay in days, md (IQR) | 7 (3.5−33) |

| Length of PICU stay in days, md (IQR) | 5 (3−19) |

| PIM2, md (IQR) | 0.0439 (0.0174−0.1670) |

| Complex chronic condition, n (%) | 32 (60.4) |

| Report of LSL, n (%) | 24 (45.3) |

| Report of DNR, n (%) | 23 (43.4) |

| Report of palliative care, n (%) | 14 (26.4) |

| Palliative extubation, n (%) | 3 (5.6) |

| Received CPR, n (%) | 30 (56.6) |

| Presence of parents at the time of death, n (%) | 37 (69.8) |

| Psychological counseling, n (%) | 34 (64.2) |

| No nutritional support in the 24h prior to death, n (%) | 36 (67.9) |

md, median; IQR, interquartile range; PICU, pediatric intensive care unit; PIM2, Pediatric Index of Mortality 2; LSL, life support limitation; DNR, do-not-resuscitate order; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

The main organ failure on admission was respiratory failure. Most patients had complex chronic conditions. Of 24 patients with a report of LSL on their medical records, only 1 did not have a DNR order. Only this patient received CPR maneuvers. In the group of patients with a report of LSL, 3 were palliatively extubated and 2 were not intubated. In the remaining 19 patients, death was due to invasive mechanical ventilation. Only 14 patients (26.4%) had a report of palliative care (Table 1).

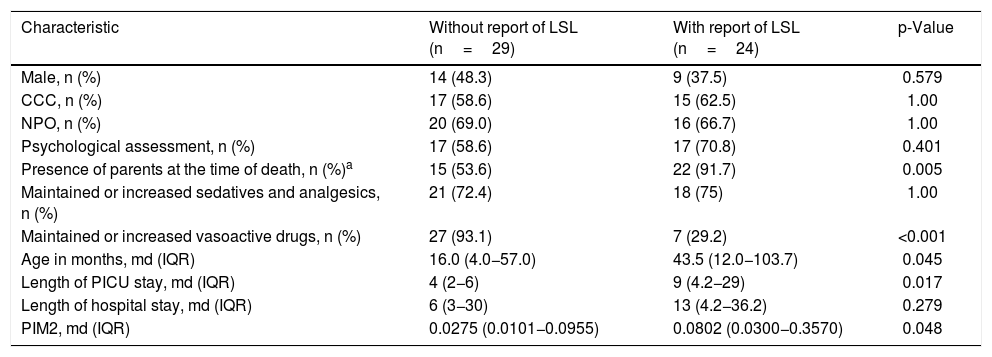

Table 2 shows the clinical and demographic characteristics, as well as death-related management strategies in patients with vs without a report of LSL on the medical records.

Clinical and demographic characteristics and death-related management between patients with and without a report of life support limitation on medical records.

| Characteristic | Without report of LSL (n=29) | With report of LSL (n=24) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male, n (%) | 14 (48.3) | 9 (37.5) | 0.579 |

| CCC, n (%) | 17 (58.6) | 15 (62.5) | 1.00 |

| NPO, n (%) | 20 (69.0) | 16 (66.7) | 1.00 |

| Psychological assessment, n (%) | 17 (58.6) | 17 (70.8) | 0.401 |

| Presence of parents at the time of death, n (%)a | 15 (53.6) | 22 (91.7) | 0.005 |

| Maintained or increased sedatives and analgesics, n (%) | 21 (72.4) | 18 (75) | 1.00 |

| Maintained or increased vasoactive drugs, n (%) | 27 (93.1) | 7 (29.2) | <0.001 |

| Age in months, md (IQR) | 16.0 (4.0−57.0) | 43.5 (12.0−103.7) | 0.045 |

| Length of PICU stay, md (IQR) | 4 (2−6) | 9 (4.2−29) | 0.017 |

| Length of hospital stay, md (IQR) | 6 (3−30) | 13 (4.2−36.2) | 0.279 |

| PIM2, md (IQR) | 0.0275 (0.0101−0.0955) | 0.0802 (0.0300−0.3570) | 0.048 |

CCC, complex chronic condition; NPO, nil per os; md, median; IQR, interquartile range; PICU, pediatric intensive care unit; PIM2, Pediatric Index of Mortality 2; LSL, life support limitation.

The 2 groups differed in the maintenance or increase of vasoactive drug dose, where more patients without a report of LSL maintained or increased the dose of these drugs. Parents were present at the time of death for almost all patients with a report of LSL. There was no difference between the 2 groups in sex, complex chronic condition, lack of nutritional support in the 24h prior to death, psychological assessment, and maintenance or increase of sedatives. Patients with a report of LSL were older, stayed longer in the PICU, and had higher severity scores on admission (PIM2). Length of hospital stay did not differ between the groups (Table 2).

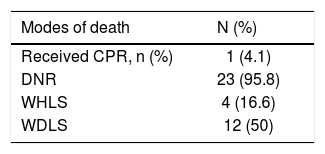

Table 3 shows the mode of death in patients with a report of LSL. Family participation in the decision-making process was reported for all patients. This means that there was at least one meeting between a medical or multidisciplinary team where the limitation of life support was addressed and its pros and cons were explained. Half of them had life support withdrawn.

Mode of death in 24 patients with a report of life support limitation.

| Modes of death | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Received CPR, n (%) | 1 (4.1) |

| DNR | 23 (95.8) |

| WHLS | 4 (16.6) |

| WDLS | 12 (50) |

CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; DNR, do-not-resuscitate order; WHLS, withholding of life support; WDLS, withdrawal of life support.

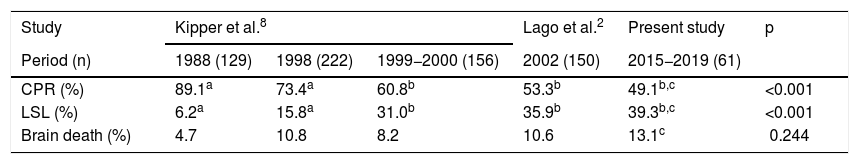

In the historical comparison of PICUs in the same geographic region, we observed a percentage increase in patients who had some form of LSL and a decrease in CPR maneuvers (Table 4). The data analysis showed a difference mainly in relation to the 2 older cohorts in the study by Kipper et al.8: the diagnosis of brain death was slightly lower in the group of the year 1988, with similar percentages thereafter (Table 4).

Comparison with previous studies of similar populations regarding modes of death.

| Study | Kipper et al.8 | Lago et al.2 | Present study | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Period (n) | 1988 (129) | 1998 (222) | 1999−2000 (156) | 2002 (150) | 2015−2019 (61) | |

| CPR (%) | 89.1a | 73.4a | 60.8b | 53.3b | 49.1b,c | <0.001 |

| LSL (%) | 6.2a | 15.8a | 31.0b | 35.9b | 39.3b,c | <0.001 |

| Brain death (%) | 4.7 | 10.8 | 8.2 | 10.6 | 13.1c | 0.244 |

CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; LSL, life support limitation.

a,bSame superscript letters indicate no difference between the groups.

cPercentage considering n=61 patients (53 patients eligible for the study+8 patients with a diagnosis of brain death).

In our study, we found a prevalence of LSL of 45.3%. When compared with other historical cohorts, a growing trend was observed for this rate over the years. The same was observed in similar studies conducted in Latin America.9,10,14 We believe that the increase in LSL mainly results from a change in mentality among multidisciplinary teams in the face of imminent death of the patient. Until the late 1980s, the practice of therapeutic obstinacy was widely used and supported in medical schools, where ethics in LSL received scant attention.15 By failing to prevent or postpone death, physicians may feel confronted by a sense of finitude and powerlessness which leads to a difficulty in accepting treatment failure and the inevitable death of the patient. LSL can be more stressful when healthcare professionals are unaware of the laws and legal implications of this practice. Therefore, proper training is essential for every physician to approach the families and make the most appropriate decision about limitation of supportive care for their patients.16

When comparing Latin American studies with studies conducted in Europe, The United States, Japan and Australia, major discrepancies are observed between them in relation to LSL. The prevalence of LSL is much higher in non-Latin American countries.17–22 However, an interesting finding of our study was the high participation of parents in decisions at the end of life, contrary to the traditional paternalistic approach in Latin American countries. According to this approach, physicians tend to assume the position of decision makers in treatment choices, without hearing the family’s opinion or the opinion of other teams involved in patient care. This increase in parental participation may indicate a change in end-of-life practices.23

Life support (vasoactive drugs or palliative extubation) was withdrawn in half of the patients with a report of LSL, a result much higher than that of previous Brazilian studies, in which the prevalence of withdrawal of life support was lower than 3.3%.2,9,10 In these studies, LSL basically consisted of DNR orders. We believe that much of this progress has resulted from the increase in the approach and importance given to the topic within PICUs, which may have helped the intensivists to better understand that treatment limitation and palliative care are different from euthanasia, which is prohibited in Brazil. Our data point to a clear change in the behavior of PICU teams. It is worth noting that at the time this study was conducted, the hospital had no multidisciplinary team to specifically treat palliative care patients, which is a common practice today in Brazil. Another important point is that previous studies have considered the fear of legal issues and lack of medical knowledge about the topic as the main reason for therapeutic obstinacy.24–26 It was only in 2010 that articles and items addressing the need and ethical duty to provide palliative care to patients with incurable and terminal illness were added to the Brazilian code of medical ethics.

In the present study, at least one family meeting was held to decide on the form of care for all patients with a report of LSL. This result is similar to that observed in studies that showed better quality of end-of-life care with LSL.19,20 However, in studies reporting rates of withholding and withdrawal of life support close to zero, parental participation was low.2,8–10 We believe that listening to family members, addressing their fears and concerns, which are common feelings in those who have a loved one in the PICU, are part of a humanized and ethical approach at the end of life. The medical record of family participation in all patients with LSL may represent that the team had this concern.

When patients were stratified into those with and without a report of LSL, it was clear that the former actually had their life-sustaining treatment limited, going far beyond the usual DNR order or minimal palliative care. Patients with a report of LSL more often had their vasoactive medication reduced or discontinued. Conversely, the 2 groups did not differ in the maintenance or increase of sedatives and analgesics in the 24h prior to death: 75% of patients with versus 72.4% of patients without a report of LSL. The number of reports of psychological counseling was also similar in both groups. These data indicate that even patients who had no LSL plan received sedatives and analgesics, in addition to psychological assessment. Therefore, despite not being properly reported in the medical records (only 26.4% of the total sample had a report of palliative care), it seems reasonable to assume that patients in general must have somehow received this type of care. A possible explanation is that, in Brazil, the term “palliative care” is culturally confused with and used to define terminal palliative care.

Longer PICU stay was associated with LSL, which is consistent with the findings of most studies. We believe that longer hospitalization gives the medical team more time to define the diagnosis, prognosis, and actions to limit life-sustaining treatment.9,27 Most studies have reported an association between longer hospitalization and complex chronic conditions, but this association was not found in the present study. Regarding severity, predicted by the PIM2 score, more severely ill patients received more LSL. Keele et al., in a large cohort in the USA, showed that catastrophic events 24h prior to hospital admission, PICU admission and high mortality scores on the first day of admission were associated to a higher likelihood of discussing limitation or withdrawal of life support.28 We speculate that this association results from the fact that it is more ethically permissible for the medical team to limit treatment of patients with worse prognosis, but this association has not been found in all previous studies evaluating severity scores.10,20

As in most retrospective studies on death, our study has some specific limitations. The study of death and of the decisions to limit life support is very complex for a number of reasons, including the use of non-validated instruments, lack of consistency in the definitions, the use of data that is not always complete, and the usual absence of objective documentation. These limitations may lead to inaccurate conclusions, which may underestimate the actual prevalence of LSL. Data were obtained by reviewing medical records, which are possibly subject to recording bias. An aggravating factor for the poor reporting of this practice in medical records is the fear of physicians of legal consequences that may result from writing about treatment limitation.23 Information in medical records about the participation of families in the LSL process was scarce, especially in the group classified as not receiving LSL, making it difficult to carry out detailed analyses. In addition, our study was conducted in a single center, which may represent the behaviors of a specific group. However, as mentioned earlier, a strength of this study is that it was conducted prior to the implementation of palliative care teams, which are now broadly used worldwide. Therefore, it will be hardly possible to perform a similar study.

In summary, our study demonstrated that LSLs were associated with older and more severely ill patients. These patients had limited life support treatment through measures such as reduction or suspension of vasoactive drugs. In addition, parental participation was high in our sample. In comparison with other historical cohorts, there was an increase in the prevalence of LSL which may be related to a change in behavior in medical and multidisciplinary teams. Knowledge about end-of-life care is still scarce in Brazil and there are still many gaps, such as the reasons that doctors do not indicate LSL or the real influence that families play in this process.

Ethical approvalThis study was approved by the institutional Research Ethics Committee. Due to its purely retrospective and descriptive design, the requirement to obtain informed consent was waived (Ethics Approval number 08966518.4.0000.5336).

FundingThis study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nivel Superior–Brasil (CAPES)–Finance Code 001. Dr. Furtado disclosed that this study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nivel Superior–Brasil (CAPES)–Finance Code 001. The funding source did not interfere in any stage of this research. The other authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Study conducted at Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul (PUCRS), Faculdade de Medicina e Terapia Intensiva Pediátrica, Hospital São Lucas, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil.