To investigate the association between birth weight and excess weight among students aged 6–14 years, adjusted for life course confounding factors.

MethodsCross-sectional study with 6–14-year-old schoolchildren in 2010; 795 school children from two public schools. In addition, a sub-sample was selected using a case-cohort study approach. Sociodemographic, breastfeeding, food introduction, previous weight gain, family history, current clinical and behavioral variables as well as maternal variables related to pregnancy, were collected. Multivariable weighted logistic regression was used to evaluate the association between birth weight and overweight. All prevalent cases of overweight (n = 160) were selected to compose the case group and a random sub-sample of all students participating in the study (n = 276 students, of whom 88 were cases) were the control group.

ResultsAn unadjusted 6% increase in the excess weight prevalence ratio (p-value = 0.004) was found for each 100 g increase in birth weight. With adjustment for age, sex and behavioral variables (models 1 and 2), the association of birth weight with excess weight was positive and statistically significant, but it was no longer significant in the final model (model 3) when clinical variables were considered.

ConclusionsAlthough some of the secondary associations were statistically significant, we could not identify a significant association between birthweight and excess weight in adolescents.

The global increase in the prevalence of childhood obesity, the persistence of excess weight gain during childhood and adolescence into adult life,1 and the possible metabolic health benefits of early intervention during childhood2 have stimulated life course research that focuses on the effects of long-term exposures acting since the gestation to adult life or across generations and the life-course pathways.3,4

Studies conducted by Barker and Osmond5 suggested that there is an association of perinatal and childhood factors with greater risk of disease in adult life. These studies introduced the fetal programming hypothesis, which suggests that babies in a restricted intrauterine environment are more likely to be born smaller than expected, while growing in a nutrient-rich environment increases the risk of developing metabolic diseases in which maternal, fetal and environmental factors interact.4 Birth weight as a proxy for fetal growth has been found to be associated with risk of cardiovascular disease in adults6, excess weight during childhood and central body fat during adolescence.7 A systematic review8 conducted in 2012 exploring risk factors in the first year of life for excess weight during childhood showed that high birth weight, rapid early weight gain, excess pre-pregnancy weight, and smoking during pregnancy increased the risk of child overweight and obesity. The review also reported that breastfeeding and late introduction of solid foods were moderate protective factors against excess weight during childhood.

Results of studies have been inconsistent, and there are knowledge gaps about fetal programming in developing countries such as Brazil.9,10 Analyzing multiple exposures and outcomes related to fetal programming, metabolic changes, and risk factors for chronic non-communicable diseases in a developing country will contribute to life course research.

The present study is justified by the high prevalence of overweight and obesity in the Brazilian population, conflicting findings regarding the association between birth weight and excess childhood weight, and dearth of research on the influence of other maternal, fetal and environmental factors. Thus, this study investigated the association between birth weight and excess weight among schoolchildren from ages 6–14 years, based on fetal programming that composes the life course epidemiology.

MethodsDesign and study populationA case-control study was conducted in 2010, which included schoolchildren from ages 6–14 years. The study sample was selected from a nutrition survey11 involving 795 school children conducted in two public schools in Niterói, Rio de Janeiro State, Brazil, which were part of the Family Physician Program (acronym in Portuguese: PMF). This life course research, based on fetal programming, aimed to investigate associations between intrauterine growth restriction, the components of the metabolic syndrome, and the thickness of carotid arteries considering the growth and socioeconomic trajectories. Further details about the study can be found elsewhere.11

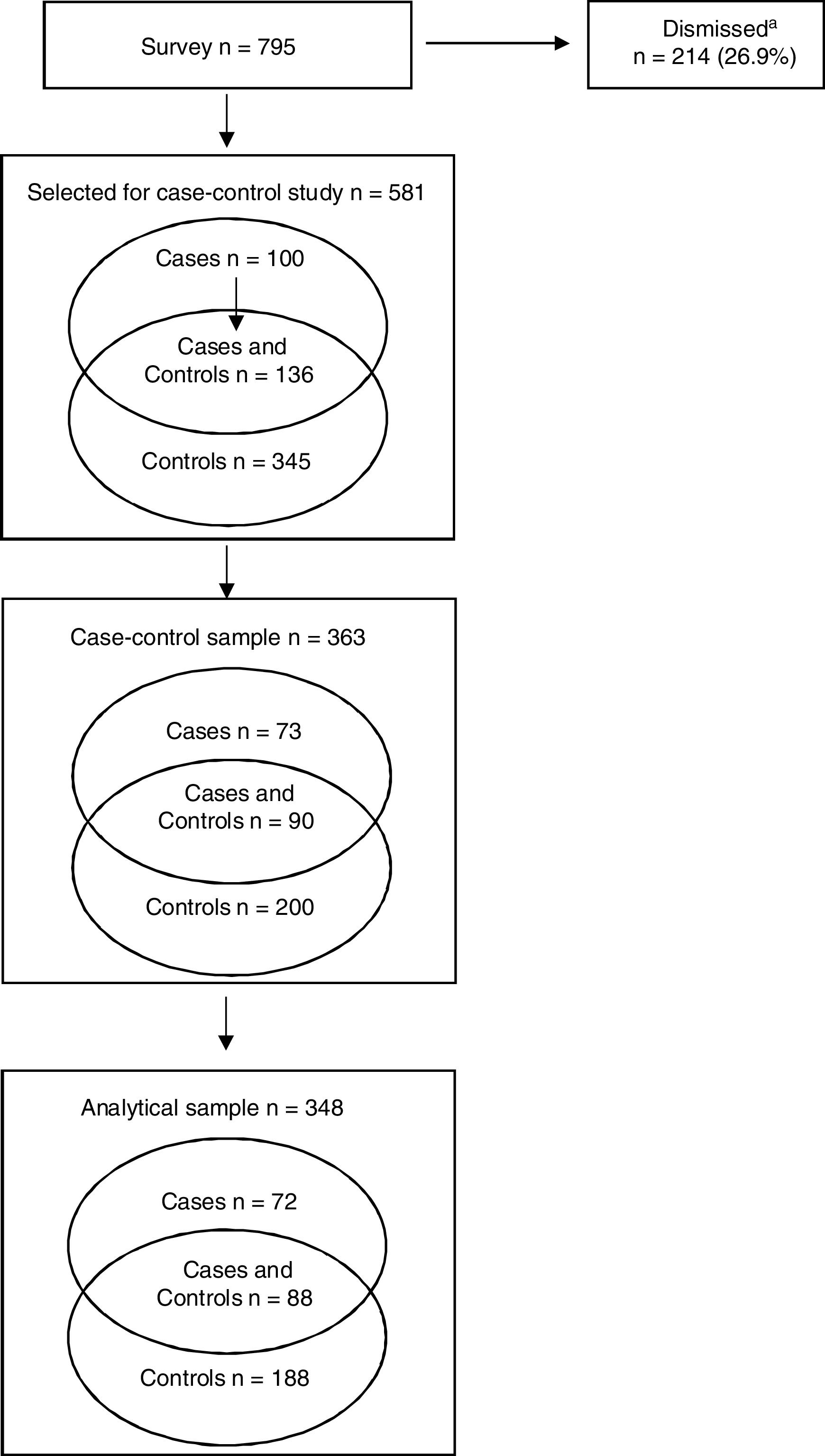

Point prevalence rates of excess weight and low birth weight (<2500 g) were 29.7% and 7.7%, respectively. All cases of excess weight from the cross-sectional study sample were selected to form the case group. Of the 236 schoolchildren selected, 32.2% refused participation, leaving an analytic sample of 160 cases (Fig. 1). Of 481 school children comprising a random subsample of all children included in the cross-sectional survey, representing the controls in the present study, 276 were included in the present analysis (67.4%). Among these 276 children, 88 were also included in the case group (Fig. 1). The two groups were stratified by school (schools A and B) and age group (6–9 years and 10–14 years). The case-control ratio was 1:1.8. Since the control group comprised a subsample of the total sample, the calculation of the point prevalence odds ratio (cases/subsample) yielded a point prevalence ratio (PR).12 This strategy was used because when the prevalence of the outcome is high, as in the present study, selecting only non-cases for the control group yields the prevalence odds ratio, which overestimates the prevalence ratio.

Data were collected by trained health professionals and post-graduate students, who were supervised by the main investigators (AJLC, MLTC, PLK).

Age- and sex-adjusted body mass index (BMI, kg/m2) z-score ≥ +1.00 was defined as excess weight.13 Height and weight were measured using a portable stadiometer with accuracy of ±0.5 cm and a calibrated digital scale with a capacity of 150 kg and accuracy of ±100 g, respectively.14 Height was measured twice. Participants were remeasured when there was a difference greater than 0.5 cm between the two measurements.

Blood pressure (BP) was measured twice using an electronic blood pressure monitor and an interval of five minutes between each measurement. The average (mean) systolic BP and diastolic BP (mmHg) was calculated. Pressure was remeasured when the difference between measurements was ≥ 5 mmHg; the measurement with the greatest discrepancy was discarded. Blood samples were collected after a 12 -h fast and two plasma samples were stored in a freezer.

The schoolchildren’s parents/guardians were interviewed to obtain information about family socioeconomic and demographic characteristics; reproductive history of the biological mother; schoolchildren’s history of breastfeeding, introduction of solid foods, and previous excessive weight gain; and family history of asthma, cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. The schoolchildren aged between 10 and 14 years were also interviewed about their life habits.

Data were also linked to neonatal medical records kept at the PMF database; 268 records were found, comprising 63.1% of cases and 60.5% of controls (subsample). Linkage to the data obtained from the State of Rio de Janeiro’s Live Birth Information System (acronym in Portuguese, SINASC) yielded 250 pairs of records, comprising 57.5% of cases and 57.2% of controls.

The validity of the information on the schoolchildren’s birth weight had been tested in a previous study.15 Perinatal information was obtained from four sources, including SINASC (official date birth data, the most reliable information). The intra-class correlation coefficients (ICCs) of the SINASC birth weight with each one of the three other sources of information varied from 0.90 to 0.99. In the absence of SINASC information, data on birth weight were obtained from other sources of information, following a decreasing order of the estimated ICCs by two-way mixed-effect-models: PMF, followed by the parent/guardian interview and self-completion of the parent/guardian questionnaire. Although records closer to the time of birth have advantages, the study conducted by Noronha et al.15 showed that recalling birth weight between 6 and 14 years after birth is a reliable option. The same algorithm used to complete the variable birth weight was used for the variable gestational age. The international standards for fetal growth,16 INTERGROWTH-21 Project, was used to identify and exclude inconsistencies between gestational age and birth weight.

Definition of exposure and covariatesBased upon the fetal programming hypothesis, the main exposure of interest was birth weight as a continuous measure that is associated with long-term disease risk.2 Birth weight measurements were converted into 100-g units to facilitate the interpretation of the results.

The following covariates were considered as potentially confounding: a) demographic variables—biological mother’s race/color (white, black, brown), household income, parent/guardian level of schooling at the time of the study (under eight years of schooling, equal to or over eight years of schooling), family size, maternal age at birth, and age in years and sex of the students; b) morbidity and behavioral maternal variables – complications during pregnancy, such as high blood pressure and diabetes (yes/no); active and passive smoking at home or work at least once a week during pregnancy (yes/no); c) clinical variables – length at birth (cm); and gestational age (preterm <37 weeks, or full-term ≥ 37 weeks to < 43 weeks); breastfeeding (months); introduction before 6 months of solid and semi-solid healthy meals (e.g. meat and/or egg and/or fruit and/or vegetables); introduction of unhealthy foods before 12 months (coffee and/or cookies and/or industrialized drinks and/or sugar); parents’/guardians’ perceptions of excessive weight gain prior to the study. Weight gain was ascertained before 2 years of age, between 2 and 6 years, between 7 and 9 years, and between 10 and 14 years. These age groups were defined considering catch-up growth in the first two years of life,17 prepubertal repletion phase, characterized by an increase of adipose tissue in preparation for the pubertal growth spurt between 7 and 10 years, and beginning of adolescence from 10 years of age on.

Additional variables included family history of cardiovascular and metabolic diseases (high blood pressure, stroke, acute myocardial infarction, diabetes, dyslipidemia, obesity) and asthma among parents and/or grandparents (yes/no); meal consumption patterns based on Prochnik Estima et al.,18 as follows: main meal frequency (breakfast, lunch, and dinner), categorized as “daily”, “three to six times a week”, “once or twice a week”, and “never or almost never”. A score of “zero” for “daily” and “three” for “never or almost never” was given for each meal, resulting in a total score for the three meals of between zero and nine. A score of zero or one was regarded as satisfactory. Comorbidities and health problems included asthma19 (yes/no); hypertension;20 high fasting blood glucose level;21 lipid profile;22 high fasting blood insulin level;21 and high C-reactive protein (CRP) blood level.22

We also investigated the association between birth weight and excess weight among schoolchildren included in the whole cross-sectional sample, which increased the sample size to 661, but limited the number of covariates. These included demographic variables, except household income and family size. The clinical variables included in the whole sample were only length at birth (cm), gestational age, exclusive breastfeeding (until 6 months), and blood pressure.

Statistical analysisMean and standard deviations were calculated for continuous variables, and proportions were calculated for the categorical variables for cases and controls. Student's t-test or the chi-squared test were used to calculate statistical significance. Linearity between the continuous variables and outcome was also tested. For adjustment for confounding variables, weighted logistic regression was used.

First, univariate analysis was conducted adopting a significance level of 0.20 for inclusion in the multivariate analysis, so as to minimize the beta error. The variables weight gain between seven and nine years and weight gain between 10 and 14 years were controlled for age and sex. Collinearity and independence between variables were tested using Pearson’s correlation matrix and the chi-squared test, respectively. Multiple regression was performed adopting a significance level of 0.05. Goodness of fit was evaluated using the Hosmer-Lemeshow test. Statistical analysis was performed using the statistical software package Stata, version 12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, United States).

Ethical standardsThis study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving research study participants were approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Institute for Collective Health Studies of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro – IESC/UFRJ (application number 77-2008). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects/patients.

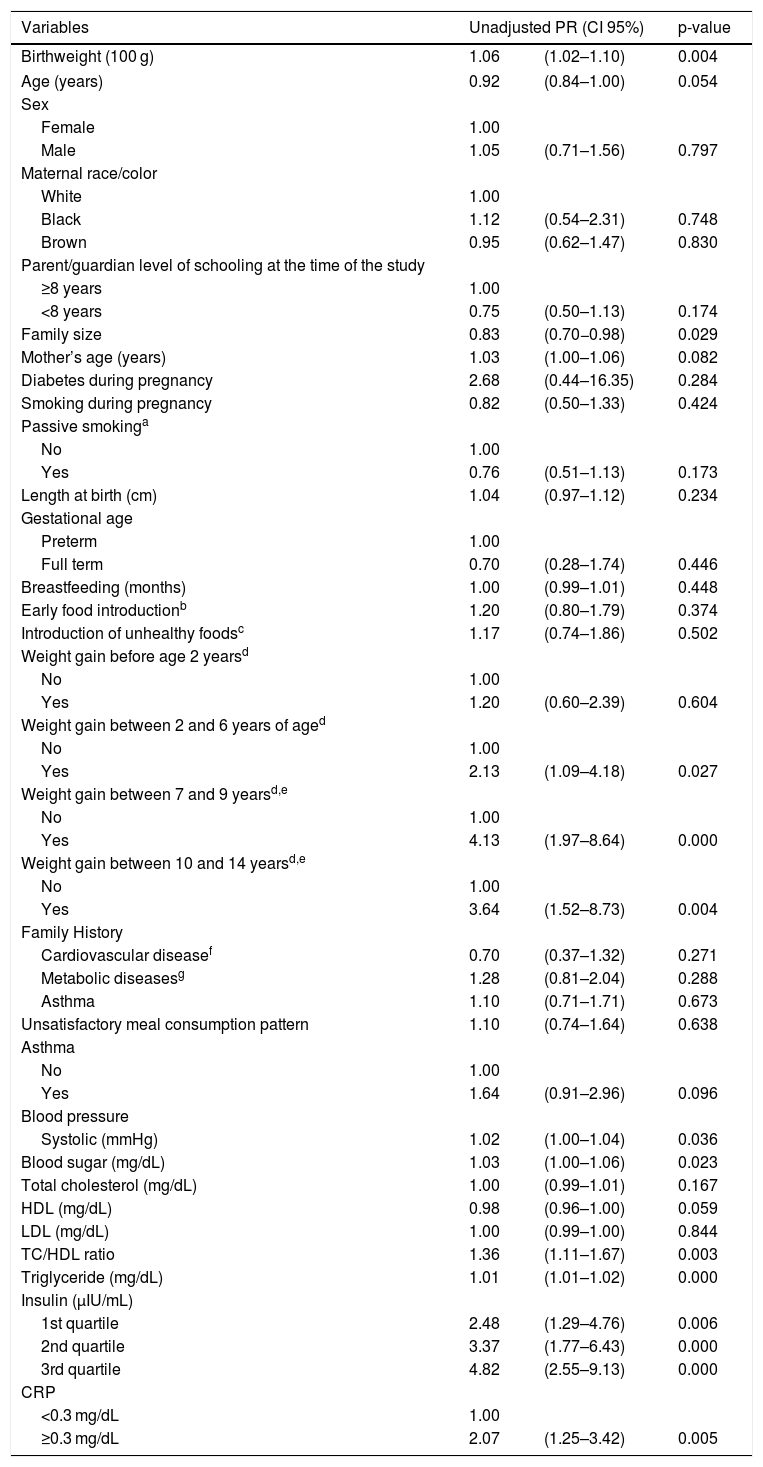

ResultsCase-control studyUnadjusted PRs of excess weight according to selected variables are shown in Table 1. This unadjusted model shows a 6% increase in the excess weight PR (p-value = 0.004) for each 100-g increase of birth weight. The following variables had a p < 0.20: age, parent/guardian level of schooling, family size, mother’s age, passive smoking, weight gain between 2 and 14 years of age, history of asthma, blood pressure, blood sugar, total cholesterol, high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL), total cholesterol/HDL ratio, triglyceride, insulin and CRP. These variables were included in the multiple regression models (Table 2). Although not statistically significant at p = 0.20, sex was entered in the multiple regression model as it could be a conditional confounder.

Unadjusted prevalence ratios of excess weight according to selected variables in schoolchildren aged between 6 and 14 years. Niterói, Rio de Janeiro, 2010.

| Variables | Unadjusted PR (CI 95%) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Birthweight (100 g) | 1.06 | (1.02–1.10) | 0.004 |

| Age (years) | 0.92 | (0.84–1.00) | 0.054 |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 1.00 | ||

| Male | 1.05 | (0.71–1.56) | 0.797 |

| Maternal race/color | |||

| White | 1.00 | ||

| Black | 1.12 | (0.54–2.31) | 0.748 |

| Brown | 0.95 | (0.62–1.47) | 0.830 |

| Parent/guardian level of schooling at the time of the study | |||

| ≥8 years | 1.00 | ||

| <8 years | 0.75 | (0.50–1.13) | 0.174 |

| Family size | 0.83 | (0.70−0.98) | 0.029 |

| Mother’s age (years) | 1.03 | (1.00–1.06) | 0.082 |

| Diabetes during pregnancy | 2.68 | (0.44–16.35) | 0.284 |

| Smoking during pregnancy | 0.82 | (0.50–1.33) | 0.424 |

| Passive smokinga | |||

| No | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 0.76 | (0.51–1.13) | 0.173 |

| Length at birth (cm) | 1.04 | (0.97–1.12) | 0.234 |

| Gestational age | |||

| Preterm | 1.00 | ||

| Full term | 0.70 | (0.28–1.74) | 0.446 |

| Breastfeeding (months) | 1.00 | (0.99–1.01) | 0.448 |

| Early food introductionb | 1.20 | (0.80–1.79) | 0.374 |

| Introduction of unhealthy foodsc | 1.17 | (0.74–1.86) | 0.502 |

| Weight gain before age 2 yearsd | |||

| No | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 1.20 | (0.60–2.39) | 0.604 |

| Weight gain between 2 and 6 years of aged | |||

| No | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 2.13 | (1.09–4.18) | 0.027 |

| Weight gain between 7 and 9 yearsd,e | |||

| No | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 4.13 | (1.97–8.64) | 0.000 |

| Weight gain between 10 and 14 yearsd,e | |||

| No | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 3.64 | (1.52–8.73) | 0.004 |

| Family History | |||

| Cardiovascular diseasef | 0.70 | (0.37–1.32) | 0.271 |

| Metabolic diseasesg | 1.28 | (0.81–2.04) | 0.288 |

| Asthma | 1.10 | (0.71–1.71) | 0.673 |

| Unsatisfactory meal consumption pattern | 1.10 | (0.74–1.64) | 0.638 |

| Asthma | |||

| No | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 1.64 | (0.91–2.96) | 0.096 |

| Blood pressure | |||

| Systolic (mmHg) | 1.02 | (1.00–1.04) | 0.036 |

| Blood sugar (mg/dL) | 1.03 | (1.00–1.06) | 0.023 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 1.00 | (0.99–1.01) | 0.167 |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 0.98 | (0.96–1.00) | 0.059 |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 1.00 | (0.99–1.00) | 0.844 |

| TC/HDL ratio | 1.36 | (1.11–1.67) | 0.003 |

| Triglyceride (mg/dL) | 1.01 | (1.01–1.02) | 0.000 |

| Insulin (μIU/mL) | |||

| 1st quartile | 2.48 | (1.29–4.76) | 0.006 |

| 2nd quartile | 3.37 | (1.77–6.43) | 0.000 |

| 3rd quartile | 4.82 | (2.55–9.13) | 0.000 |

| CRP | |||

| <0.3 mg/dL | 1.00 | ||

| ≥0.3 mg/dL | 2.07 | (1.25–3.42) | 0.005 |

PR, prevalence ratio; BMI, body mass index; HDL, high density lipoprotein; LDL, low density lipoprotein; CT, total cholesterol; CRP, C-reactive protein.

Multivariate-adjusted prevalence ratios of excess weight according to selected variables in schoolchildren aged between 6 and 14 years. Niterói, Rio de Janeiro, 2010.

| Variables | Model 1a PR (CI 95%) | p-value | Model 2b PR (CI 95%) | p-value | Model 3c PR (CI 95%) | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birth weight (in 100 g) | 1.05 | 1.01−1.10 | 0.010 | 1.05 | 1.01−1.10 | 0.019 | 1.04 | 0.99−1.09 | 0.110 |

| Age (years) | 0.92 | 0.83−1.02 | 0.121 | 0.92 | 0.83−1.02 | 0.123 | 0.84 | 0.73−0.95 | 0.010 |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Female | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Male | 1.04 | 0.67−1.59 | 0.864 | 1.00 | 0.65−1.54 | 0.992 | 1.43 | 0.83−2.45 | 0.199 |

| Parent/guardian level of schooling at the time of the study | |||||||||

| ≥8 years | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| <8 years | 0.87 | 0.56−1.36 | 0.554 | 0.85 | 0.54−1.33 | 0.479 | 0.78 | 0.46−1.32 | 0.361 |

| Family size | 0.81 | 0.67−0.98 | 0.030 | 0.80 | 0.66−0.97 | 0.025 | 0.82 | 0.65−1.02 | 0.079 |

| Mother’s age (years) | 1.02 | 0.99−1.06 | 0.167 | 1.02 | 0.99−1.05 | 0.181 | 1.01 | 0.97−1.04 | 0.581 |

| Passive smokingd | |||||||||

| No | – | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Yes | – | 0.87 | 0.55−1.36 | 0.538 | 0.74 | 0.43−1.27 | 0.281 | ||

| Weight gain between 2 and 6 years of agee | |||||||||

| No | – | – | 1.00 | ||||||

| Yes | – | – | 1.11 | 0.42−2.91 | 0.825 | ||||

| Weight gain between 7 and 9 yearse | |||||||||

| No | – | – | 1.00 | ||||||

| Yes | – | – | 2.82 | 1.07−7.45 | 0.036 | ||||

| Weight gain between 10 and 14 yearse | |||||||||

| No | – | – | 1.00 | ||||||

| Yes | – | – | 3.01 | 0.91−9.98 | 0.070 | ||||

| Asthma | |||||||||

| No | – | – | 1.00 | ||||||

| Yes | – | – | 1.70 | 0.80−3.63 | 0.169 | ||||

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | – | – | 1.00 | 0.97−1.03 | 0.716 | ||||

| Blood sugar (mg/dL) | – | – | 1.00 | 0.97−1.04 | 0.739 | ||||

| CT/HDL ratio | – | – | 1.05 | 0.81−1.36 | 0.692 | ||||

| Triglyceride (mg/dL) | – | – | 1.01 | 1.01−1.02 | 0.042 | ||||

| Insulin (μIU/mL) | |||||||||

| 1st quartile | – | – | 1.80 | 0.87−3.76 | 0.113 | ||||

| 2nd quartile | – | – | 2.54 | 1.16−5.54 | 0.019 | ||||

| 3rd quartile | – | – | 2.29 | 0.94−5.54 | 0.067 | ||||

| CRP | |||||||||

| <0.3 mg/dL | – | – | 1.00 | ||||||

| ≥0.3 mg/dL | – | – | 1.52 | 0.78−2.97 | 0.212 | ||||

PR, prevalence ratio; CT, total cholesterol; HDL, high density lipoprotein; CRP, C-reactive protein.

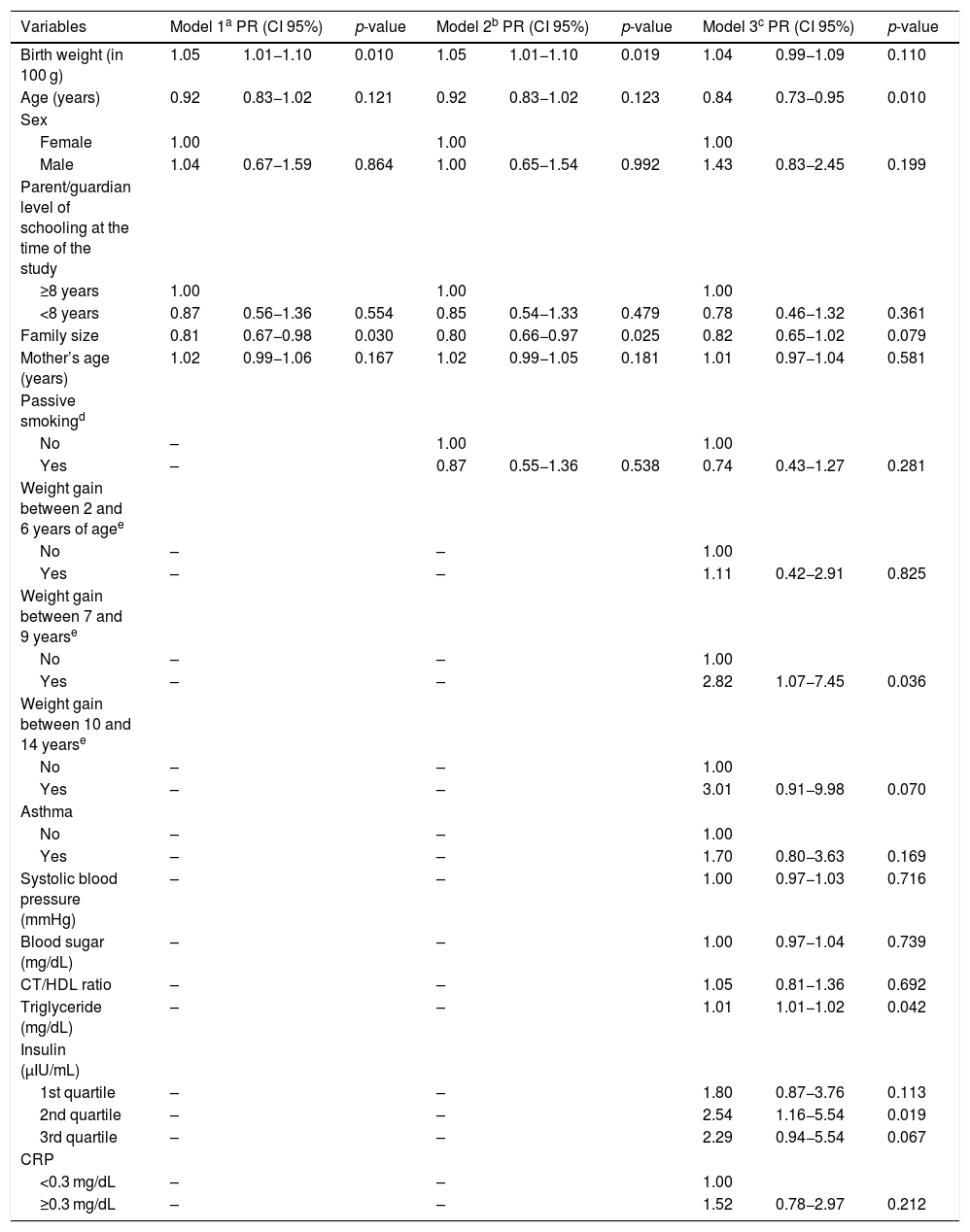

Model 1: demographic variables (age, sex, parent/guardian level of schooling at the time of the study, number of people in the family [or family size], mother’s age).

With adjustment for age, sex and behavioral variables (models 1 and 2), the association of birth weight with excess weight was positive and statistically significant, but it was no longer significant in the final model (model 3) when clinical variables (previous parents’/guardians’ perceptions of excessive weight gain, asthma, systolic blood pressure, blood sugar, total cholesterol/HDL ratio, triglyceride, insulin, CRP) were considered.

The following additional covariables showed a significant association with excess weight: age, weight gain between 7–9 years, and blood triglyceride and insulin levels. The final model showed a good fit to the data (p-value = 0.485), and the assumptions of linearity and no collinearity were preserved.

Cross-sectional analysis of the whole sampleThe unadjusted model shows a 6% increase in the excess weight PR (p-value < 0.0001) for each 100-g increase of birth weight, as in the case-control study. In the multivariate model, birth weight was statistically and positively associated with excess weight (PR = 1.05 p-value = 0.025) after adjustment for age, sex, mother’s age, race/color, schooling, length at birth and systolic blood pressure.

DiscussionIn this study, we didn´t find a statistically significant association between birth weight and excess weight during childhood and adolescence, which therefore failed to support the hypothesis of fetal programming of excess weight. Several studies have shown inconsistent results, suggesting that further research on this topic is necessary.9,23–26

In a systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between birth weight and excess weight among children and adolescents,24 14 studies reported a positive association between high birth weight (>4000 g) and risk of excess weight, and 10 studies showed a negative association between low birth weight (<2500 g) and excess weight. In the latter studies, the association disappeared when two studies including children of low socioeconomic status were excluded.

In a large-scale cross-sectional population-based survey26 conducted in China that included 70,284 children aged 3–12 years, low birth weight (< 2500 g at birth, irrespective of gestational age) was positively associated with an increased risk of thinness and severe obesity but not associated with moderate obesity. On the other hand, high birth weight seemed to have a protective effect on thinness26 and was associated with an increased risk of childhood obesity.27 In a study in Poland,25 birth weight was positively related to BMI in 747 4−15-year-old children; however, no significant differences were found in birth weight with overweight/obese children.

A matched case-control study of the impact of prenatal, perinatal and postnatal risk factors for obesity in children aged between 4 and 8 years conducted with 1024 pairs in various European countries9 reported negative and positive associations between obesity and low birth weight (below 2500 g) and obesity and high birth weight (over 4000 g), respectively. After weighting the data using an indicator of fat-free mass, the association of birth weight with obesity risk disappeared completely.

A cohort study conducted in 1993 with 5160 newborns in Pelotas, Brazil,23 showed in the adjusted analysis that for each increase of unit (Z-score) in birth weight, the BMI increases 0.46 kg m−2 in BMI at age 11 years, regardless of sex.

Although not the focus of this study, the associations we found between the covariables and excess weight, previous excessive weight gain,10,28 high blood insulin,29,30 and triglyceride levels29 are consistent with the findings of other studies. During pubescence, there is a physiological increase in circulating insulin, thus contributing to rapid growth and body modification.30 Nevertheless, the association between a lower proportion of muscle tissue, derived from intrauterine growth restriction, and a greater proportion of fat mass, derived from catch-up growth, may increase predisposition to chronic non-communicable diseases in the future.10 In individuals who have suffered malnutrition in the uterine environment and start to have a diet rich in calories, their fetal programming to develop an economic metabolism becomes harmful.4 Fetal metabolic adaptation increases the risk of obesity, diabetes, and other chronic diseases.4 There is strong evidence that cardiovascular diseases begin to develop early in life, meaning that it is vital to monitor main risk factors from childhood, particularly among people who are overweight.29

Life course epidemiological studies of excess weight tend to be prospective birth cohort studies, which have proved to be ideal for evaluating etiological hypotheses. However, they are particularly complex and require long periods of time, which can result in losses to follow-up and the need for substantial funding, often rendering research difficult.4 Considering these limitations, case-cohort study designs can enhance the feasibility of research, as they are less costly and more efficient, making them a useful alternative for obtaining almost as much information as in a full cohort.12 Furthermore, the availability of multiple, wide-ranging secondary sources of data on the period up to 2 years of age allowed our study to capture reliable and valid information on the main exposure variable, birth weight.15 In addition, and notwithstanding the cross-sectional study design, temporality of the events, birth weight and overweight in childhood and adolescence are accurately recorded.

The study had a number of limitations. First, the sample size resulted in a low frequency of low birthweight. Second, previous weight gain depended not only on the parents’/guardians’ memory, but also on their perceptions. Third, the limited availability of accurate data on gestational age meant that it was only possible to consider a single dichotomous variable (preterm or full term). Finally, it was not possible to identify the time of the occurrence of the outcome.

In conclusion, the present study provides valuable information on the association between birth weight and excess weight in a sample of schoolchildren aged 6–14 years. Although the main relationship hypothesized in this study was not statistically significant, statistically significant associations were found between excess weight and age, weight gain between 7 and 9 years of age, blood triglyceride and insulin levels.

Financial SupportConselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico-CNPq- (MCT/CNPq 15/2007–Universal; n° 481094/2007-5); Fundação Carlos Chagas Filho de Amparo à Pesquisa no estado do Rio de Janeiro-FAPERJ (E-26 110.986/2008); Financiadora de Estudos e Projetos- FINEP/ Ministério da Ciência e Tecnologia – FINEP; Departamento de Ciência e Tecnologia – DECIT- Ministério da Saúde (0436/08).

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The authors would like to acknowledge the insightful comments from IESC teachers and doctoral students, in particular Dr. Katia Vergetti Bloch. We also thank all the schoolchildren and guardians who agreed to participate in the study.