This study aimed to correlate amplitude-integrated electroencephalography findings with early outcomes, measured by mortality and neuroimaging findings, in a prospective cohort of infants at high risk for brain injury in this center in Brazil.

MethodsThis blinded prospective cohort study evaluated 23 preterm infants below 31 weeks of gestational age and 17 infants diagnosed with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy secondary to perinatal asphyxia, with gestational age greater than 36 weeks, monitored with amplitude-integrated electroencephalography in a public tertiary center from February 2014 to January 2015. Background activity (classified as continuous, discontinuous high-voltage, discontinuous low-voltage, burst-suppression, continuous low-voltage, or flat trace), presence of sleep-wake cycling, and presence of seizures were evaluated. Cranial ultrasonography in preterm infants and cranial magnetic resonance imaging in infants with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy were performed.

ResultsIn the preterm group, pathological trace or discontinuous low-voltage pattern (p=0.03) and absence of sleep-wake cycling (p=0.019) were associated with mortality and brain injury assessed by cranial ultrasonography. In patients with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, seizure patterns on amplitude-integrated electroencephalography traces were associated with mortality or brain lesion in cranial magnetic resonance imaging (p=0.005).

ConclusionThis study supports previous results and demonstrates the utility of amplitude-integrated electroencephalography for monitoring brain function and predicting early outcome in the studied groups of infants at high risk for brain injury.

Este estudo visou correlacionar os achados do eletroencefalograma de amplitude integrada (aEEG) com resultados precoces, medidos por mortalidade e achados de neuroim- agem, em uma coorte prospectiva de neonatos com risco elevado de lesão cerebral em nosso centro no Brasil.

MétodosO estudo prospectivo de coorte cego avaliou 23 neonatos prematuros abaixo de 31 semanas de idade gestacional (IG) e 17 neonatos diagnosticados com Encefalopatia Hipóxico-Isquêmica (EHI) secundária à asfixia perinatal, com IG superior a 36 semanas, monitorados com aEEG em um centro terciário público de fevereiro de 2014 a janeiro de 2015. Foram avaliadas a atividade de base (classificada como padrão contínuo, descontínuo de alta voltagem, descontínuo de baixa voltagem, supressão de explosão, contínuo de baixa voltagem ou traço plano), a presença de ciclo do sono-vigília e a presença de convulsões. Foram feitas a ultrassonografia craniana em prematuros e a ressonância magnética (RM) craniana em neonatos com EHI.

ResultadosNo grupo de prematuros, o traço patológico ou padrão descontínuo de baixa voltagem (p=0,03) e a ausência de ciclo do sono-vigília (p=0,019) foram associados a mortalidade e lesão cerebral avaliada por ultrassonografia craniana. Em pacientes com EHI, os padrões de convulsão nos traçados do aEEG foram associados a mortalidade ou lesão cerebral na RM craniana (p=0,005).

ConclusãoEste estudo corrobora os resultados anteriores e demonstra a utilidade do aEEG no monitoramento da função cerebral e na predição de alterações precoces nos grupos de neonatos estudados com risco elevado de lesão cerebral.

The incidence of neurodevelopmental impairment in extremely preterm infants and those with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) secondary to perinatal asphyxia remains high in spite of advances in perinatal care. Studies have estimated a global incidence of 345,000 premature infants and 233,000 infants with HIE per year with moderate/severe neurological impairment.1,2 Both populations are considered at high risk for brain injury.

Different imaging methods can evaluate brain injury and assess neurological prognosis.3–5 Acute electroencephalographic abnormalities result from neuronal disorganization and correlate with cognitive impairment.6,7 Amplitude-integrated electroencephalography (aEEG) provides a clinically accessible method for continuous observation of cerebral background activity in ill infants at the bedside. Thus, the utility of early aEEG for the assessment of the severity of cerebral injury and adverse outcomes in premature infants has been investigated as a tool for assessing initial neonatal risk.8–10

The aEEG pattern is well correlated with conventional EEG, and results in term newborns with perinatal asphyxia showed good predictive value of short- and long-term neurological prognosis.11–13 Other studies have shown that severe electroencephalographic abnormalities in preterm neonates evaluated during the first 72h of life are related to neurodevelopmental impairment.14,15

Given the severity of brain injury, as well its high morbidity and mortality rate, the identification of prognostic factors with appropriate timing to provide early future interventions is relevant. Therefore, this study aimed to correlate aEEG findings with early outcomes, measured by mortality and neuroimaging findings, in a prospective cohort of infants at high risk for brain injury in this center in Brazil.

MethodsThis study was performed in a public tertiary center in Brazil. All infants born between February 2014 and January 2015, with gestational age (GA) above 36 weeks with HIE secondary to perinatal asphyxia or with GA below 31 weeks, were prospectively included in the study after parental consent was obtained. All subjects included were inborn. The study was approved by the institutional ethics committee. Infants with genetic syndromes or congenital malformations incompatible with life were excluded, as these conditions could affect the results.

The criteria for perinatal hypoxic-ischemic events included the presence of at least two of the following: (a) Apgar score below 5 at 5min; (b) need for ventilation up to 10min of life (intubation or ventilation under continuous positive airway pressure); (c) gas analysis of cord blood in the first hour of life with pH<7.10 or BE>−12. The modified clinical Sarnat score was used to grade HIE.16 The aEEG was recorded for 72h as a two-channel EEG from biparietal surface disk electrodes using an EEG device (Neuron-Spectrum-4 and 5 systems with Neurospectrum software module for aEEG and trending – Neurosoft, Russia). Newborns with HIE who were treated with the institutional hypothermia protocol were evaluated for an additional 24h in order to monitor the rewarming phase. In brief, the obtained signal was filtered, rectified, smoothed, and amplitude-integrated before it was printed out or digitally available on the monitor at a slow speed (6cm/h), directly at the bedside.

The recordings were analyzed by two independent readers and registered as shown below17:

- 1)

Background activity:

- -

Continuous voltage pattern (CVP): continuous activity with minimum amplitude above 5μV and maximum amplitude above 10μV.

- -

Discontinuous voltage pattern (DC): discontinuous activity with minimum amplitude below 5μV and maximum amplitude above 10μV. For preterm evaluation this study also used the sub-classification proposed by Olischar et al.18 and this pattern was further subdivided into: (a) discontinuous high voltage pattern (DHVP) – minimum range between 3 and 5μV; (b) discontinuous low voltage pattern (DLVP) – minimum range below 3μV.

- -

Burst suppression: discontinuous activity with minimum amplitude without variability at 0–1/2μV, and bursts with amplitude >25μV.

- -

Inactive, flat trace (FT): mainly inactive background (electrocerebral inactivity) with amplitude always below 5μV.

- -

- 2)

Sleep-wake cycling (SWC): characterized by sinusoidal smooth cyclic variations, mainly of the minimum amplitude. It was further categorized as developed SWC, immature SWC, and no SWC.

- 3)

Seizures: characterized as an abrupt rise in minimum and maximum amplitude, categorized as single seizures (no more than one seizure per each period of 30min of analysis), repetitive seizures (more than one electrographic seizure per each 30min period of analysis but no more than one electrographic seizure over a 10min period), or status epilepticus (ongoing seizure activity >30min, present as “sawtooth pattern” or as continuous increase of the lower and upper margins, or more than one electrographic seizure over a 10min period).19

- 4)

Newborns with HIE were further assessed by time to normal trace (TTNT): calculated by the number of hours of life to regain normal aEEG activity (continuous voltage pattern).

To characterize background activity, 4-h periods of adequate monitoring were evaluated daily on days 1, 2, and 3 of life. Both aEEG readers were blinded to the clinical history. Cranial ultrasound (cUS) was performed at least once a week in the neonatal period and cranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed in all infants with HIE between days four and ten of life. Clinical and imaging data were collected including with pre-established interest variables, such as demographic (sex, maternal age, race), clinical (birth weight, gestational age, Apgar scores, diagnosis of early-onset sepsis, presence of clinical seizure, need for ventilatory support, surfactants, and vasoactive drugs), and imaging data. The MRI examinations were assessed by two independent neuroradiologists without knowledge of the clinical data or aEEG findings. Since the interpretation agreement among different MRI raters may affect the reliability of results, the interobserver agreement was also evaluated in this study. MRI was performed with T1 spin echo sequences; T1 MTC; T2 FSE; diffusion; and T2 gradient-echo. Four radiographic findings were evaluated: lesions in the posterior limb of the internal capsule (PLIC) – labeled as present or absent; lesions in the basal ganglia and thalamus (BGT), white matter, and cortical gray matter, labeled as normal, mild, moderate, or severe.

In the premature group, good early outcome was defined as survival to 28 days without severe periventricular/intraventricular hemorrhage (PIVH), defined as grade III or IV, or peri-ventricular leukomalacia (PVL), while poor early outcome was considered as neonatal death or presence of severe PIVH or PVL. In newborns from the HIE group, good early outcome was defined as survival without moderate/severe lesion assessed by cranial MRI, while poor early outcome was considered as death or moderate/severe lesion assessed by cranial MRI. Presence of PIVH was evaluated according to Papile classification. The HIE cohort pattern of brain injury was classified according to abnormalities in brain regions known to be susceptible in HIE, based on criteria published by Rutherford et al.20

Statistical analysisA descriptive analysis was performed using percentage and number of valid cases for categorical variables as well as mean, standard deviation, and number of valid cases for continuous variables in order to identify the main characteristics of patients with high risk for brain injury monitored with aEEG. Fisher's exact test was used for analysis of categorical variables and the t-test for comparisons of continuous variables using Stata software (Stata Corp. 2013, Stata Statistical Software, version 13, USA), considering a 5% significance level for all tests. Positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and risk ratio (RR) were evaluated. For inter-rater agreement analysis, the kappa coefficient (κ) was applied, using the SPSS v. 19.0 software.

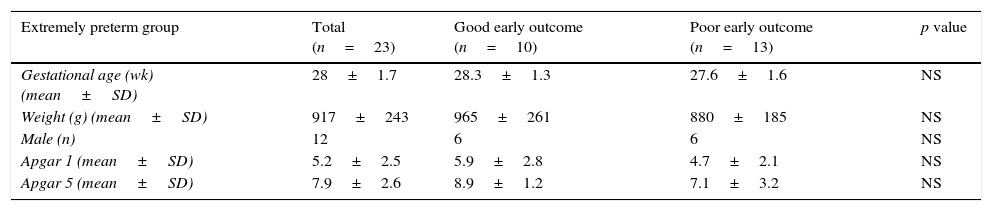

ResultsPatientsDuring the study period, a total of 40 patients were included; 23 extremely premature neonates and 17 with HIE. In the group of extremely preterm infants, gestational age ranged from 26 to 30.4 weeks, with a mean of 28 weeks; birth weight ranged from 610g to 1310g, with a mean of 938g. Eight infants in this group died during the study period. In the HIE group, gestational age ranged from 36 to 40.6 weeks, with a mean of 39 weeks; birth weight ranged from 2280g to 3940g, with a mean of 3100g, and one infant died. The baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of monitored groups.

| Extremely preterm group | Total (n=23) | Good early outcome (n=10) | Poor early outcome (n=13) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational age (wk) (mean±SD) | 28±1.7 | 28.3±1.3 | 27.6±1.6 | NS |

| Weight (g) (mean±SD) | 917±243 | 965±261 | 880±185 | NS |

| Male (n) | 12 | 6 | 6 | NS |

| Apgar 1 (mean±SD) | 5.2±2.5 | 5.9±2.8 | 4.7±2.1 | NS |

| Apgar 5 (mean±SD) | 7.9±2.6 | 8.9±1.2 | 7.1±3.2 | NS |

| HIE group | Total (n=17) | Good early outcome (n=11) | Poor early outcome (n=6) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational age (wk) (mean±SD) | 39±1.5 | 39.3±1 | 38.6±2.2 | NS |

| Weight (g) (mean±SD) | 3100±422 | 3139±217 | 3029±680 | NS |

| Male (n) | 14 | 8 | 6 | NS |

| Apgar 1 (mean±SD) | 2.2±1 | 2.2±0.9 | 2.3±1.3 | NS |

| Apgar 5 (mean±SD) | 4.7±1.3 | 4.8±1 | 4.7±1.8 | NS |

| Sarnat score (n) | ||||

| Mild encephalopathy | 0 | 0 | 0 | NS |

| Moderate encephalopathy | 10 | 6 | 4 | NS |

| Severe encephalopathy | 7 | 5 | 2 | NS |

| Therapeutic hypothermia (n) | 17 | 11 | 6 | NS |

HIE, hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy; wk, weeks; SD, standard deviation.

All patients started monitoring within the first day of life (mean 6.2h of life, range 2–16h of life) and were monitored for 72–96h after birth. Pathological aEEG trace was defined as flat tracing, burst-suppression, and continuous low-voltage pattern.

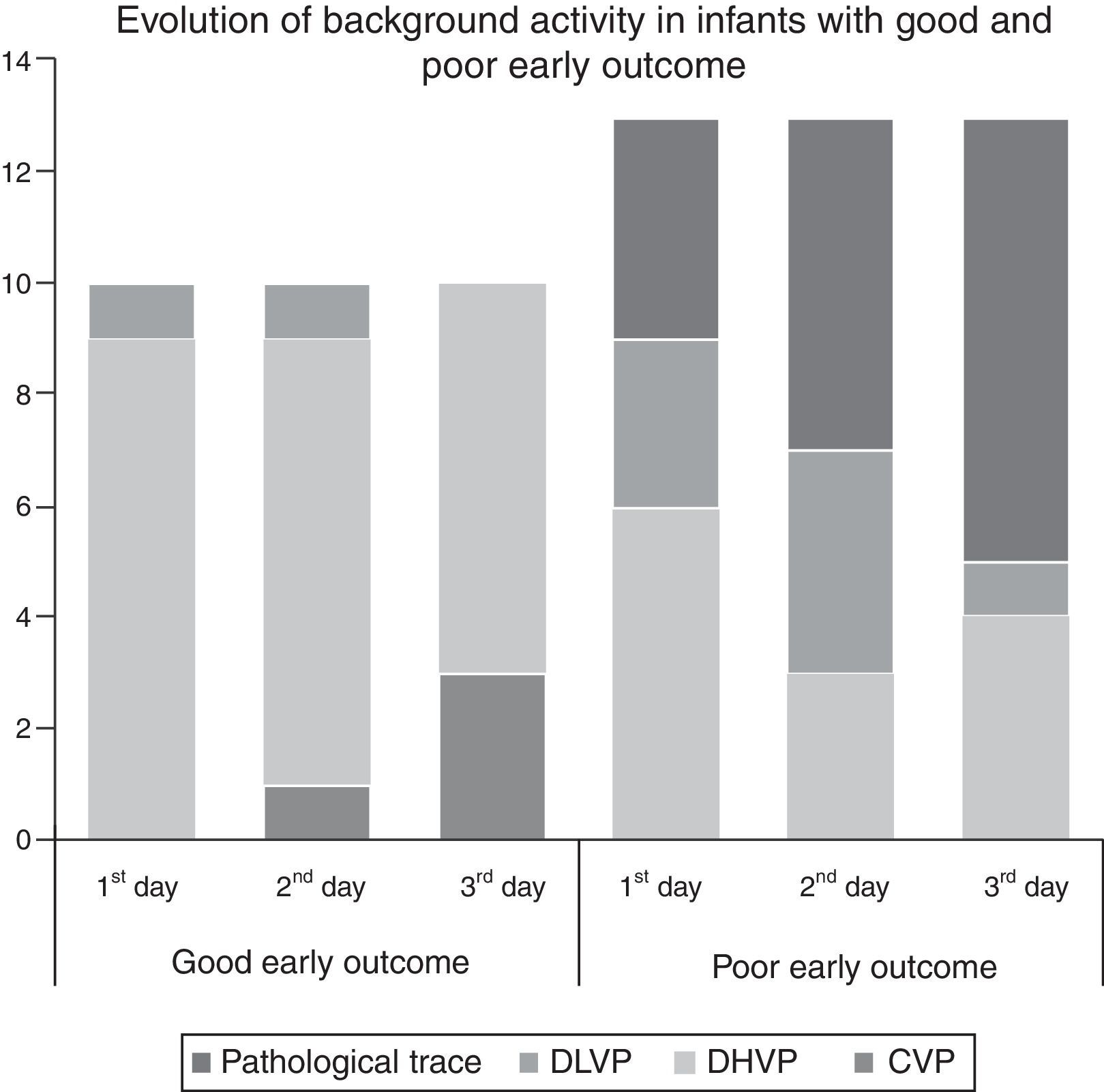

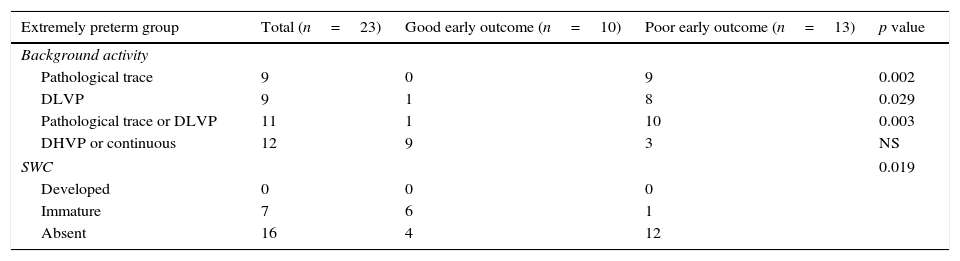

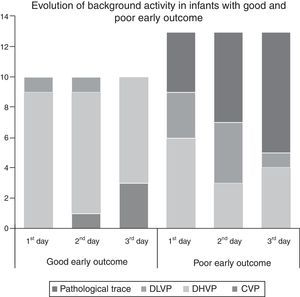

Extremely preterm newbornsIn the preterm group, mean time to initiate aEEG monitoring was 5.2 (±1.2) h of life, and pathological trace or DLVP were associated with higher rates of poor early outcome (p=0.03, PPV 90.9%, NPV 75%, RR=3.63). Absence of SWC was associated with poor early outcome (p=0.019, PPV 75%, NPV 87.5%, RR=1.53). The results are shown in Table 2. The background activity of patients with poor early outcome changed from normal to pathological aEEG pattern in five patients (38.4%), while in one (7.6%) it changed from pathological to normal aEEG pattern. None of the patients with good early outcome developed pathological aEEG pattern during the period of monitoring. Evolution of aEEG background activity in patients with poor early outcome and good early outcome is shown in Fig. 1.

aEEG findings related to outcome in extremely preterm and HIE groups.

| Extremely preterm group | Total (n=23) | Good early outcome (n=10) | Poor early outcome (n=13) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Background activity | ||||

| Pathological trace | 9 | 0 | 9 | 0.002 |

| DLVP | 9 | 1 | 8 | 0.029 |

| Pathological trace or DLVP | 11 | 1 | 10 | 0.003 |

| DHVP or continuous | 12 | 9 | 3 | NS |

| SWC | 0.019 | |||

| Developed | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Immature | 7 | 6 | 1 | |

| Absent | 16 | 4 | 12 | |

| HIE group | Total (n=17) | Good early outcome (n=11) | Poor early outcome (n=6) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| aEEG background activity, 3–6h of life | NS | |||

| Continuous | 11 | 9 | 2 | NS |

| Not continuous | 6 | 2 | 4 | NS |

| TTNT (mean) | 12.17 | 5.36 | 24.7 | 0.015 |

| Presence of SWC | 11 | 9 | 2 | NS |

| Seizures (n) | 6 | 1 | 5 | 0.005 |

| Single seizures | 0 | 0 | 0 | NS |

| Repetitive seizures | 3 | 1 | 2 | NS |

| Status epilepticus | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0.029 |

| Repetitive or status epilepticus | 6 | 1 | 5 | 0.005 |

| Clinical seizures | 4 | 1 | 3 | NS |

aEEG, amplitude-integrated electroencephalography; HIE, hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy; DLVP, discontinuous low-voltage pattern; DHVP, discontinuous high-voltage pattern; SWC, sleep-wake cycling; TTNT, time to normal trace.

Patients with HIE were assessed for background activity in the first hours of life, TTNT, presence of SWC, and seizures. Seizure patterns on aEEG traces (p=0.005, PPV 83.3%, NPV 90.9%, RR=5.45) and longer TTNT (p=0.015) were associated with poor early outcome. All the patients with HIE underwent therapeutic hypothermia. The results are shown in Table 2.

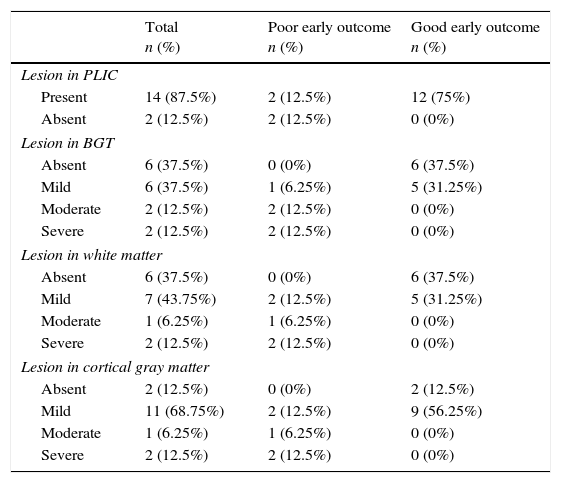

Imaging findingsCranial ultrasound findings in the extremely preterm group were as follows: nine (39%) had normal cranial ultrasound, one (4.3%) had PIVH grade I, four (17.3%) had PIVH grade II, four (17.3%) had PIVH grade III, and three (13%) had PIVH grade IV. Three (13%) infants developed PVL and cranial ultrasound was not performed in two due to early premature death. MRI findings in infants with HIE are shown in Table 3. MRI was not performed in one of the patients due to premature death.

MRI findings in infants with HIE.

| Total n (%) | Poor early outcome n (%) | Good early outcome n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lesion in PLIC | |||

| Present | 14 (87.5%) | 2 (12.5%) | 12 (75%) |

| Absent | 2 (12.5%) | 2 (12.5%) | 0 (0%) |

| Lesion in BGT | |||

| Absent | 6 (37.5%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (37.5%) |

| Mild | 6 (37.5%) | 1 (6.25%) | 5 (31.25%) |

| Moderate | 2 (12.5%) | 2 (12.5%) | 0 (0%) |

| Severe | 2 (12.5%) | 2 (12.5%) | 0 (0%) |

| Lesion in white matter | |||

| Absent | 6 (37.5%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (37.5%) |

| Mild | 7 (43.75%) | 2 (12.5%) | 5 (31.25%) |

| Moderate | 1 (6.25%) | 1 (6.25%) | 0 (0%) |

| Severe | 2 (12.5%) | 2 (12.5%) | 0 (0%) |

| Lesion in cortical gray matter | |||

| Absent | 2 (12.5%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (12.5%) |

| Mild | 11 (68.75%) | 2 (12.5%) | 9 (56.25%) |

| Moderate | 1 (6.25%) | 1 (6.25%) | 0 (0%) |

| Severe | 2 (12.5%) | 2 (12.5%) | 0 (0%) |

MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; HIE, hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy.

Interobserver agreements between radiologists regarding injury of the BGT, white matter, and cortical gray matter were: 75% (κ=0.636; p<0.001); 56.3% (κ=0.321; p=0.029), and 81.3% (κ=0.586; p<0.001), respectively. The observed agreement between radiologists regarding the PLIC was 100% (κ=1.0; p<0.001). Analyses of the normal/mild and moderate/severe injury groups of the BGT, white matter, and cortical gray matter were: 100% (κ=1.0; p<0.001); 87.5% (κ=0.589; p=0.009), and 93.8% (κ=0.764; p<0.001), respectively.

DiscussionThis study was performed to evaluate the correlation between electroencephalic disorders and early outcome in a prospective cohort of infants at high risk for brain injury in a sample of the Brazilian population. The absence of SWC in the first 72h of life and the presence of pathological trace or DLVP activity were associated with severe PIVH or death in the neonatal period. Infants with poor early outcome more commonly changed from normal to pathological aEEG pattern than the opposite. These findings support the findings of Soubasi et al.,10 which showed a sensitivity of 89% and 70%, and specificity of 80% and 80.7% for background activity (pathological trace or DLVP) and absence of SWC, respectively, for the occurrence of adverse outcomes (PIVH grade III/IV, PVL, or death). A recent prospective cohort study demonstrated that preterm infants with severe cerebral lesions already manifest a maturational delay in the aEEG cyclic activity soon after birth.21 Others studies have also reported a significant positive correlation between the degree of abnormality of the aEEG and both USG abnormalities and poor neurodevelopmental prognosis.22,23

In newborns with HIE, the presence of seizures (repetitive seizures or status epilepticus) patterns on aEEG/EEG traces and longer TTNT were associated with moderate to severe lesions observed on MRI and death. Earlier studies also found an association between electrographic seizures and severity of findings on cranial MRI.24,25 A retrospective review of continuous aEEG data from encephalopathic newborns treated with whole-body hypothermia found association between delay of aEEG background recovery as increasingly predictive of adverse early outcome over time in newborns being treated with therapeutic hypothermia.26 Thoresen et al. have described that the recovery time to normal background pattern was the best predictor of poor outcome by the age at 2 years in neonates with birth asphyxia.27 A recent meta-analysis showed that aEEG can be used as predictive and prognostic tool in preterm infants, with a specificity of 93% and sensitivity of 84%.28

The present study showed a good interobserver agreement in MRI evaluations; however, should this be interpreted with caution due to the small sample size.

Strengths of this study included an independent and blinded radiographic review and the use of two-channel montage associated with the interpretation of raw EEG technique (aEEG/EEG), as it is known to increase the sensitivity and specificity of the method.29,30 Limitations of the study were the relatively small sample size, the lack of stratification by the use of antiepileptic drugs, sedation or other medications which might potentially influence the aEEG trace, and lack of knowledge regarding timing of brain injury, especially in the preterm group, in which injury could occur after the period of aEEG monitoring.

In conclusion, this study confirms that previous results are applicable to the studied population, and thus aEEG is a justified tool in the neonatal intensive care unit to monitor this group of neonates at high risk for brain injury.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Variane GF, Magalhães M, Gasperine R, Alves HC, Scoppetta TL, Figueredo RJ, et al. Early amplitude-integrated electroencephalography for monitoring neonates at high risk for brain injury. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2017;93:460–6.