to compare physical performance and cardiorespiratory responses in the six-minute walk test (6MWT) in asthmatic children with reference values for healthy children in the same age group, and to correlate them with intervening variables.

Methodsthis was a cross-sectional, prospective study that evaluated children with moderate/severe asthma, aged between 6 and 16 years, in outpatient follow-up. Demographic and spirometric test data were collected. All patients answered the pediatric asthma quality of life (QoL) questionnaire (PAQLQ) and level of basal physical activity. The 6MWT was performed, following the American Thoracic Society recommendations. Comparison of means was performed using Student's t-test and Pearson's correlation to analyze the 6MWT with study variables. The significance level was set at 5%.

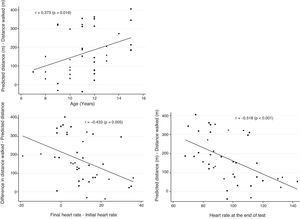

Results40 children with moderate or severe asthma were included, 52.5% males, 70% with normal weight and sedentary. Mean age was 11.3±2.1 years, mean height was 1.5±0.1 m, and mean weight was 40.8±12.6 Kg. The mean distance walked in the 6MWT was significantly lower, corresponding to 71.9%±19.7% of predicted values; sedentary children had the worst values. The difference between the distance walked on the test and the predicted values showed positive correlation with age (r=0.373, p=0.018) and negative correlation with cardiac rate at the end of the test (r=-0.518, p<0.001). Regarding QoL assessment, the values in the question about physical activity limitations showed the worst scores, with a negative correlation with walked distance difference (r=-0.311, p=0.051).

Conclusionsasthmatic children's performance in the 6MWT evaluated through distance walked is significantly lower than the predicted values for healthy children of the same age, and is directly influenced by sedentary life style.

comparar o desempenho físico e cardiorrespiratório do teste de caminhada de seis minutos (TC 6min) em crianças asmáticas com valores de referência para saudáveis da mesma faixa etária e correlacioná-los com variáveis intervenientes.

Métodosestudo transversal, prospectivo, em crianças com asma moderada/grave, entre seis e 16 anos, em acompanhamento ambulatorial. Coletaram-se dados demográficos e espirométricos. Os pacientes responderam questionário de qualidade de vida em asma (PAQLQ) e nível de atividade física basal. O TC 6min foi realizado segundo recomendações da American Thoracic Society. Para comparações de médias usou-se teste t e correlação de Pearson para analisar o TC 6min com variáveis estudadas. Nível de significância de 5%.

Resultadosincluídas 40 crianças, 52,5% meninos, 70% eutróficas e sedentárias. A média de idade 11,3±2,1 anos, altura 1,5±0,1 m e peso 40,8±12,6 Kg. A média da distância percorrida no TC 6min foi significativamente inferior correspondendo a 71,9%±19,7 dos valores previstos, onde as crianças sedentárias exibiram os piores valores. A diferença entre a distância percorrida no teste e os valores preditos mostrou correlação positiva com a idade (r=0,373, p=0,018) e negativa com a frequência cardíaca ao final do teste (r=-0,518, p<0,001). Na avaliação da qualidade de vida, os valores do quesito limitações das atividades físicas, demonstraram pior pontuação com correlação negativa com a diferença das distâncias percorridas (r=-0,311, p=0,051).

Conclusõeso desempenho do TC6min em crianças asmáticas avaliado através da distância percorrida é significativamente inferior aos valores previstos para saudáveis da mesma faixa etária, sendo influenciado diretamente pelo sedentarismo.

Asthma is a common disorder, characterized by an inflammatory status in which many cells and mediators have strong participation.1,2 It affects patients and their families, in a complex and prolonged way.2 The prevalence in Brazil among schoolchildren and adolescents is estimated at 19% and 24%, respectively, with regional variations.3

Asthmatic children are generally less active than their healthy peers.4 This reduction in physical activity is justified by factors such as attitude towards illness, family taboos, poorly grounded advice, and inaccurate perception of symptoms, among others.4,5 The reduced capacity to exercise, participate in recreational activities, and even dyspnea itself result in functional limitations, so that a vicious cycle is created, thus progressively deteriorating cardiac performance.4–6

A sedentary lifestyle can be among the most often cited risk factors for increased prevalence and severity of asthma.6 Rasmussen et al. showed that in 757 Danish children, decreased physical activity correlated with the onset of asthma in adolescence.7 Recently, it was observed that children with asthma have reduced maximal oxygen uptake and muscle endurance in the lower limbs, when compared to healthy children.8

The objective measurement of physical fitness in asthmatic children appears important to determine exercise capacity in order to guide physical activity and rehabilitation that is adequate to disease severity.9

Walking tests are used to evaluate the functional capacity of patients with pulmonary disease with limited effort. They are easy to perform, reproducible, inexpensive, and present good correlation with maximal oxygen consumption obtained in maximal cardiopulmonary exercise testing.10,11

In spite of the description of submaximal exercise tests in adults with pulmonary disease,12 the literature is scarce in asthmatic children, especially those with moderate and severe disease. When researching the past ten years in PubMed (using the keywords

exercise, test, child, asthma), it can be observed that most studies have focused on exercise-induced bronchospasm, leaving unclear the issue of functional capacity assessment and its association with pulmonary function, physical activity, body mass index, medication use, and quality of life (QoL), which justifies this study.

Thus, this study aimed to compare the physical performance and cardiorespiratory responses obtained in the six-minute walking test (6MWT) in children with moderate and severe asthma with reference values for healthy age-matched controls, and to correlate these results with possible intervening variables.

Material and methodsA cross-sectional, prospective study was conducted with a nonrandom sample of children allocated consecutively, with moderate and severe persistent asthma, defined according to the IV Brazilian guidelines for the management of asthma,1 aged between 6 and 16 years. They were recruited from the outpatient pediatric pulmonology and respiratory physical therapy clinic from the Instituto de Medicina Integral Professor Fernando Figueira (IMIP), from October of 2011 to March of 2013. At assessment, the children were clinically stable, outside the crisis period, and had cognitive capacity to perform the procedures.

Patients with other chronic pulmonary or musculoskeletal diseases were excluded from the study, as well as those with a cognitive impairment that prevented understanding of the requirements of the tests. Parents and guardians signed an informed consent, and the study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of IMIP, under number (1900-10). No monetary compensation was offered to any of the study participants.

Test procedure and data collectionAfter an interview to complete patient history and identification, data were collected regarding the assessment of physical activity level at baseline, weight and height measurement, and the QoL questionnaire was applied. Finally, the pulmonary function test was applied, and the children were referred to perform the 6MWT. The tests were performed by the main investigator (LBA) and a properly trained professional (DARGS).

To assess the level of physical activity at baseline, a score was applied, which was adapted from the habitual level of physical activity (HLPA) questionnaire by Santuz et al.13 In it, the gradations were established as: 0 (sedentary), 1 (regular activity up to two hours a week), and 2 (competitive activity or performed for more than two hours a week).

The measurement of height (m) and weight (kg) was performed in an anthropometric scale (Filizola - São Paulo, SP, Brazil) with children barefoot and wearing light clothing (shorts and T-shirts). After the measurements, participants were classified as eutrophic, overweight, and obese, according to body mass index for the gender.

Pulmonary functionThe assessment of pulmonary function by spirometry was performed using a portable digital spirometer (Clement Clarke International - England; OneFlow model) and the technical procedures, and criteria for acceptability and reproducibility followed the norms of ATS/ERS (American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society).14 The forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), forced vital capacity (FVC), peak expiratory flow (PEF), and FEV1/FVC ratio were determined. For spirometry assessment, children did not use a short-acting bronchodilator during the four hours before the test. A five to ten-minute resting period was necessary before the test was performed.

After receiving the instructions, the children were asked to start the test. A maximal inspiration was emphasized, followed by a fast maximal expiration, following the criteria established by ATS.14 The tests were performed individually in the standing position using a nose clip. For best viewing of results, spirometric values were expressed in absolute values and percentages of predicted values.15

6MWTSubmaximal functional capacity was evaluated through the 6MWT, according to ATS standards,11 in a level corridor 30 meters long. After resting for 20minutes, the children were instructed to walk as far as possible for six minutes without running, knowing that they could interrupt the test at any time. They were verbally encouraged at every minute, according to the standardization, and at the end of the six minutes, they were asked to stop where they were and the total distance in meters was recorded.

The parameters evaluated in the pre- and post-test included heart rate (HR) and pulse oxygen saturation (SpO2) by pulse oximetry (EMAI, model OXP-10 Medical Hospital Equipment - São Paulo, Brazil), blood pressure through a sphygmomanometer (CE0050, Tycos, Welch Allyn - Skaneateles Falls, New York, United States), respiratory rate (RR) (counted by chest wall movements per minute), and the score in the modified Borg scale to measure dyspnea intensity.16 The criteria for test interruption were: severe dyspnea or fatigue expressed by the patient, SpO2<85%, or refusal to continue the test.

Based on the reference values suggested by Priesnitz et al.17 for healthy Brazilian children, the predicted walked distance in the 6MWT was calculated for children with asthma using the formula 6MWT=145.343+[11.78×Age (years)]+[292.22×height (m)]+[0.611×(HR Final-HR Initial)] - [2.684×weight (kg)] for evaluation of test performance. The choice of this formula is justified by the fact that it is the only equation developed for Brazilian children, even though it was designed for healthy individuals. Furthermore, the predicted distance calculation takes into account other variables that were evaluated in the study, including age, height, and weight. Based on these values, the mean difference between the distance walked by the patient in the 6MWT (DWpat) and the predicted walked distance (DWpred) were obtained.

QoL in asthmatic patientsQoL assessment was performed using the Pediatric Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (PAQLQ), validated for Portuguese.18 The PAQLQ contains 23 questions for the age group of 7 to 17 years, and comprises three domains: symptoms (ten questions), physical activity limitations (five questions), and emotions (eight questions). Questions are asked in person, without the presence of parents, and were directed to the patient's experiences in the week prior to interview. The assessment is measured through a seven-point response scale, where 1 indicates maximum impairment, and 7, no impairment; thus, the higher the final value, the better the patient's QoL.18,19 The results were expressed as the means of total scores.

Statistical analysisFor numerical variables that showed an approximately normal distribution, data were expressed as mean and standard deviation. Categorical variables were expressed as percentages.

Student's t-test was used for comparison of means. The correlation between the difference in the distance walked in 6MWT and the predicted distance with intervening variables (pulmonary function, weight, height, HR, HR difference, Borg, and QoL) was assessed using Pearson's correlation coefficient (symmetric distribution). The significance level was set at 5%, and the analyses and data processing were performed using STATA 12.1 SE.

ResultsA total of 40 children with moderate and severe asthma, with mean age 11.3±2.1 years, of whom 52.5% were males, were included in the study. The sample characterization with anthropometric and lung function data, trophism, baseline physical activity level, medication use, and distance walked in the 6MWT are shown in Table 1.

Characterization of the study sample.a

| Analyzed variables | Value |

|---|---|

| Age (years) (mean±SD) | 11.3±2.1 |

| Male gender | 52.5% |

| Weight (kg) (mean±SD) | 40.8±12.6 |

| Height (m) (mean±SD) | 1.5±0.1 |

| BMI (mean±SD) | 18.7±3.5 |

| Eutrophic | 70% |

| Overweight/obese | 30% |

| Pulmonary function (% of predicted) | |

| FEV1 | 79%±0.12 |

| FVC | 88%±14 |

| FEV1/FVC ratio | 0.84%±0.09 |

| PEF | 341.3±66.6 |

| Basal level of physical activity (hours/week) | |

| Sedentary | 70% |

| >two activities | 30% |

| Type of asthma | |

| Moderate | 35% |

| Severe | 65% |

| Use of medications | |

| ICs low/medium dose | 40% |

| ICs low/medium dose+long acting β2 | 60% |

| 6MWT | |

| Distance walked by patient (m) | 430.4±116.7 |

| Predicted distance (m) | 600.5±42.9 |

BMI, body mass index; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in one second; FVC, forced vital capacity; ICs, inhaled corticosteroids; PEF, peak expiratory flow; SD, standard deviation; 6MWT, six-minute walk test; β2, beta-agonist bronchodilators.

The mean distance walked in the 6MWT (DWpat) was 430.3±116.7 m, while the mean distance predicted by the formula (DWpred) was 600.5±42.9 m; this difference was significant (p<0.001). DWpat represented 71.9±19.7% of DWpred. The greater the difference between DWpat and DWpred, the lower the physical fitness and conditioning of the child.

Table 2 shows the comparison of means between DWpat with clinical and demographic variables. There was a significant influence of baseline physical activity level, as sedentary children walked a shorter distance than active ones.

Comparison of walked distance, according to demographic and clinical variables.

| Variable | n | Mean | SD | Minimum | Maximum | p-value a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.778 | |||||

| Male | 21 | 435.4 | 136.7 | 240.0 | 650 | |

| Female | 19 | 424.8 | 93.3 | 226.6 | 564 | |

| Type of asthma | 0.807 | |||||

| Moderate | 14 | 424.1 | 105.6 | 240.0 | 602 | |

| Severe | 26 | 433.7 | 124.2 | 226.6 | 650 | |

| Basal level of activity | 0.040b | |||||

| Sedentary | 28 | 409.0 | 110.6 | 226.6 | 602 | |

| Physical activity up to two hours | 10 | 495.9 | 110.2 | 260.0 | 650 | |

| >three hours | 2 | 402.1 | 185.5 | 270.9 | 533 | |

| Weight | 0.515 | |||||

| Eutrophic | 28 | 422.4 | 111.7 | 248.0 | 650 | |

| Overweight/Obesity | 12 | 449.1 | 130.8 | 226.6 | 607 | |

| Medications used | 0.461c | |||||

| ICs low/medium dose | 16 | 418.6 | 133.1 | 240.0 | 649.5 | |

| ICs low/medium dose+long-acting β2 | 23 | 446.5 | 100.9 | 226.6 | 602.2 | |

| ICs high dose+long-acting β2 | 1 | 248.0 | - | 248.0 | 248.0 | |

ICs, inhaled corticosteroids; SD, standard deviation; β2, beta-agonist bronchodilators.

The difference of DWpat with DWpred showed a positive correlation with age (r=0.373, p=0.018), and a negative correlation with HR at the end of the test (r=-0.518, p<0.001) and the difference of HR (before and after the 6MWT) (r=-0.359, p=0.023), as shown in Fig. 1.

Regarding the assessment of QoL, the overall mean of PAQLQ scores was 5.13±1.24. The item that showed the greatest impairment on the children's QoL was physical activity limitations (4.89±0.11), followed by symptoms (5.03±1.55), and finally, emotions (5.18±0.14).

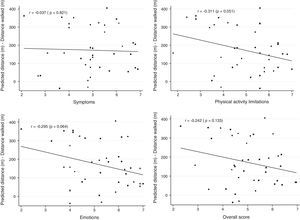

A negative correlation of the difference of DWpat with DWpred was observed only with the activity limitation criterion (r=-0.311, p=0.051). Regarding the criteria of emotions and symptoms, as well as the overall mean of the questionnaire, no significant correlation was observed (Fig. 2).

DiscussionThe results demonstrated that children with moderate and severe asthma walked a shorter distance in the 6MWT than the predicted values for healthy children, averaging 71.9% of the predicted distance for age and height. This difference suggests a lower level of fitness in this population.

Several anthropometric, clinical, and emotional factors can influence the distance walked in a walk test, both in healthy and sick individuals. This study demonstrated that children who had lower baseline physical activity, that is, were more sedentary, walked a shorter distance in the 6MWT when compared to those that practiced more than two or three hours of weekly physical activities. Corroborating this finding, Teoh et al. reported that up to 30% of asthmatic children had exercise limitations, with reduced daily physical activity.20 Iwana et al. also found a significant correlation between the baseline level of physical activity and the distance walked in the 6MWT in asthmatic children.21

Previous studies indicate that several factors may influence the capacity of asthma patients to exercise; among them, the level of habitual activity is often cited.21,22 It is stated that although the symptoms of the disease lead children to avoid physical activity, according to current treatment guidelines, the diagnosis of asthma should not prevent a child from practicing physical activity, as moderate intensity physical activity is a recognized goal of disease control.4,23

An American study of 137 asthmatic children demonstrated that they are less active than their peers in all classifications used to define physical activity level.23 In Germany, a survey was conducted in 46 schools; 254 physical education teachers were interviewed, and it was observed that only 60% of asthmatic children participated in physical activities.24

Children with respiratory disease may have reduced physical activity, either due to primary respiratory limitations or secondary causes. A negative feedback can be created, where the reduction in habitual activities causes deconditioning, leading to a reduction in exercise capacity. This may impact the child's overall health status, well-being, and QoL.19 Lang et al. demonstrated that children whose parents believe that exercise can improve asthma control are more active.22

Another study that also assessed functional capacity in children with asthma found that 88% of asthmatics and 56% of healthy children performed less than two hours of physical activity weekly; this difference was significant. It was also shown that parents considered physical activities to be dangerous to their children, for fear of triggering crises, according to their responses to a questionnaire.25 Thus, most children are exempted from the mandatory physical activity in schools, a fact also observed, although not measured, in several children in the present study.

It is known that the quantification of daily physical activity through questionnaires has the advantage of being low cost and easy to apply; however, it depends on factors such as understanding of the information and individual characteristics such as age, culture and educational level. Studies with motion sensors are suggested so that a sample of confirmed sedentary individuals can be evaluated.

No association was observed in the present study between the distance walked in the 6MWT and gender, asthma severity, trophism, or medication use. In accordance with the present results, another study also did not observe an association between physical fitness and asthma severity; however, it reported a strong association of maximal oxygen uptake with psychological factors, such as perceived competence during physical activity and attitudes towards exercise.23

Gender did not influence the distance walked by the children in several studies with healthy individuals;17,26,27 this result can be explained by the greater musculoskeletal similarity between the genders before adolescence. Regarding BMI, the results with healthy children are differing.17,27 There have been no reports in the literature on the influence of medication use and the performance in the 6MWT.

In this study, the difference in DWpat and DWpred was evaluated, suggesting that the greater the difference, the lower the physical fitness and conditioning of the child. This difference in distance walked was positively correlated with age, thus older children showed greater difference. Studies with healthy children have reported that the older the child, the greater the distance walked in the test.17,26,28 These results are in contrast with those of the present study, and can be justified by the fact that the present sample had 65% of children with severe asthma, which may explain the low exercise capacity in this population. It must be emphasize that no studies demonstrating this correlation with asthmatic children were retrieved.

A negative correlation was also observed between the difference in distance walked with HR at the end of the test and the difference in HR (before and after 6MWT), where children who performed better on the test, i.e., were closer the predicted values, showed higher HR at the end of the test and higher difference in HR values. As expected, HR increased when walking longer distances in response to the required physiological demands, matching better performance in the test.

Some studies conducted in healthy children have demonstrated a correlation between height and gender with the distance walked; taller children and male children had better performance.17,26,27 However, this association was not observed in the present study.

It is suggested that the assessment of QoL should be incorporated into clinical evaluation, as chronic illnesses affect the different dimensions of patients’ lives. The QoL of asthmatic children can be influenced by a number of interacting factors, such as symptom severity, morbidity, gender, and capacity to cope with difficulties, demonstrating a clear association between QoL impairment and asthma.19,29 In the present study, a overall mean PAQLQ score of 5.13±1.24 was observed, indicating good QoL; however, when the items were evaluated separately, a worse mean value was observed regarding the aspect of limitation of activities. This value was negatively correlated with the difference between the DWpat and DWpred, indicating that children with more physical limitations had a worse performance in the test.

Some studies have also shown similar values of total PAQLQ score in asthmatic children, with averages ranging from 5.03±0.730 to 5.7±1.3.29 In the study by Basaran et al.,30 similarly to the present study, the score that showed the worst value was limitation of activities, where 86% had difficulty in running, 52% in climbing, and 38% in playing soccer or other sports.

Reduced levels of physical activity, while there has been an increase in the incidence and prevalence of asthma in children, is of concern, as it may result in a growing number of asthmatic patients who will fail to achieve good health and QoL.4

Formal exercise tests, such as the 6MWT, may help determine whether the etiology of reduced exercise capacity in children with respiratory disease is due to the cardiorespiratory limitation or physical deconditioning. Many authors have reported that the numerical value of FEV1 poorly reflects patients’ daily experiences, and does not assess the impact of asthma on the individual concerned.29,30 Therefore, it is suggested that submaximal exercise tests may be incorporated into the evaluation of these patients.

The small sample size, the sedentary life style assessment, and the lack of studies with asthmatic children to compare results are the main limitations of this study. Future studies incorporating such requirements, in addition to the inclusion of comparison groups and maximum stress tests, may contribute to the clarification of the subject.

In conclusion, the results of the present study demonstrated that the assessed children with moderate and severe asthma showed worse performance in the 6MWT when the distance walked was compared to predicted values for healthy children; a sedentary lifestyle was the main factor that influenced the walked distance. The difference between the values of the DWpat and the DWpred was lower in younger children and in those with higher HR at the end of the test.

QoL had a good overall score, but it presented worse values regarding the physical activity limitation item, which correlated with a greater difference in the distance walked values. A better understanding of the associations and evolution of functional capacity is a relevant pediatric clinical issue, contributing to improve the follow-up of children with asthma

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: de Andrade LB, Silva DA, Salgado TL, Figueroa JN, Lucena-Silva N, Britto MC. Comparison of six-minute walk test in children with moderate/severe asthma with reference values for healthy children. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2014;90:250–7.