To characterize a cohort of children with non-neurogenic daytime urinary incontinence followed-up in a tertiary center.

MethodsRetrospective analysis of 50 medical records of children who had attained bladder control or minimum age of 5 years, using a structured protocol that included lower urinary tract dysfunction symptoms, comorbidities, associated manifestations, physical examination, voiding diary, complementary tests, therapeutic options, and clinical outcome, in accordance with the 2006 and 2014 International Children's Continence Society standardizations.

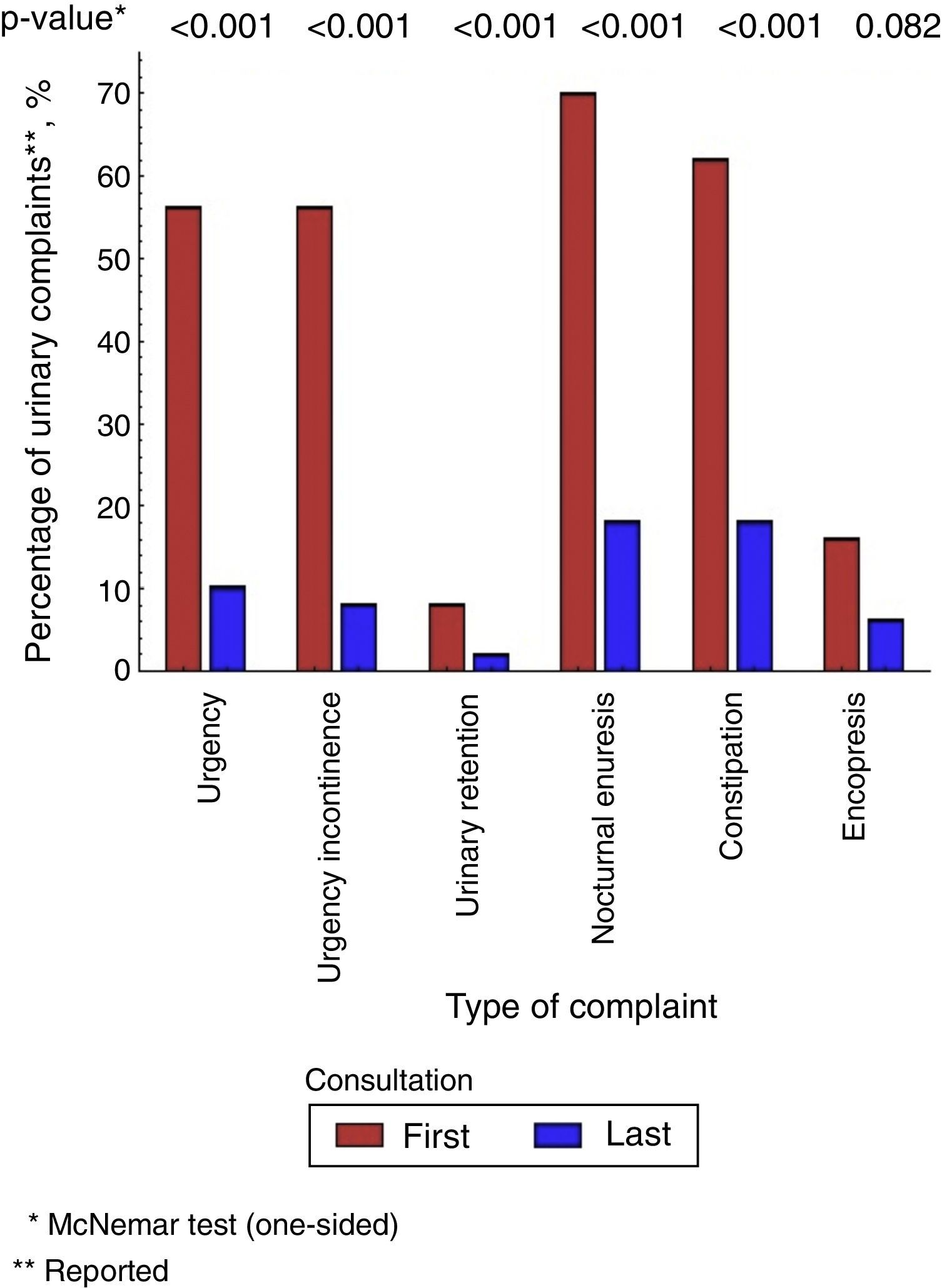

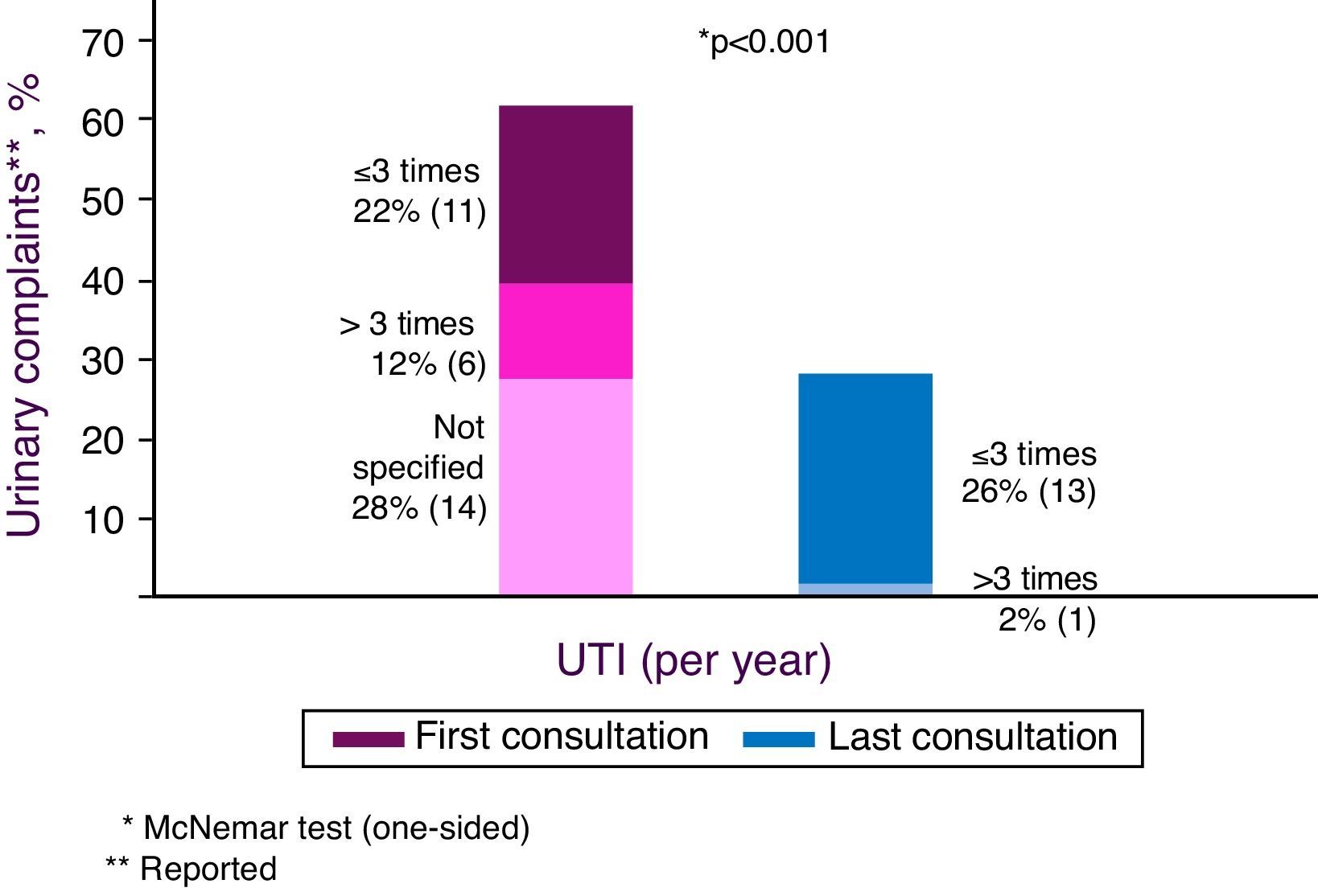

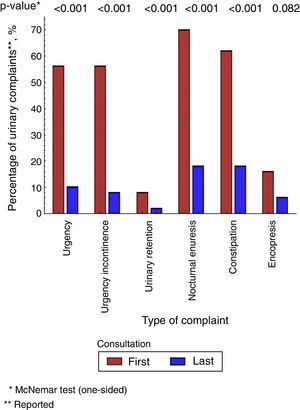

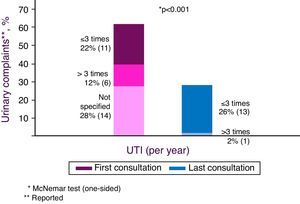

ResultsFemale patients represented 86.0% of this sample. Mean age was 7.9 years and mean follow-up was 4.7 years. Urgency (56.0%), urgency incontinence (56.0%), urinary retention (8.0%), nocturnal enuresis (70.0%), urinary tract infections (62.0%), constipation (62.0%), and fecal incontinence (16.0%) were the most prevalent symptoms and comorbidities. Ultrasound examinations showed alterations in 53.0% of the cases; the urodynamic study showed alterations in 94.7%. At the last follow-up, 32.0% of patients persisted with urinary incontinence. When assessing the diagnostic methods, 85% concordance was observed between the predictive diagnosis of overactive bladder attained through medical history plus non-invasive exams and the diagnosis of detrusor overactivity achieved through the invasive urodynamic study.

ConclusionsThis subgroup of patients with clinical characteristics of an overactive bladder, with no history of urinary tract infection, and normal urinary tract ultrasound and uroflowmetry, could start treatment without invasive studies even at a tertiary center. Approximately one-third of the patients treated at the tertiary level remained refractory to treatment.

Caracterizar uma coorte de crianças com incontinência urinária diurna não neurogênica acompanhada em serviço terciário.

MétodosAnálise retrospectiva de 50 prontuários de crianças com controle miccional ou idade mínima de cinco anos, por meio de protocolo estruturado, que incluiu sintomas de disfunção do trato urinário inferior, comorbidades, manifestações associadas, exame clínico, diário miccional, exames subsidiários, opções terapêuticas e evolução clínica, conforme normatizações da International Children's Continence Society, de 2006 e 2014.

ResultadosEram do sexo feminino 86% dos pacientes. A idade média foi de 7,9 anos e o seguimento médio de 4,7 anos. Urgência (56,0%), urge-incontinência (56,0%), retenção urinária (8,0%), enurese noturna (70,0%), infecção do trato urinário (62,0%), constipação (62,0%) e perda fecal (16,0%) foram os principais sintomas e comorbidades. Exames de ultrassom apresentaram alterações em 53,0% dos casos, e o estudo urodinâmico, em 94,7%. Na última consulta, 32,0% dos pacientes ainda apresentavam incontinência urinária. Ao analisar os métodos diagnósticos, observou-se concordância de 85,0% entre o diagnóstico preditivo de bexiga hiperativa obtido pela história clínica mais exames não invasivos e o diagnóstico de hiperatividade detrusora obtido pelo estudo urodinâmico

ConclusãoO subgrupo de pacientes com quadro clínico característico de bexiga hiperativa, sem antecedentes de infecção urinária, ultrassom de vias urinárias e urofluxometria normal poderia iniciar tratamento sem a necessidade de estudos invasivos, inclusive em serviço terciário. Aproximadamente um terço dos pacientes com incontinência urinária atendidos em serviços terciários permanecem refratários ao tratamento.

Functional urinary incontinence (UI) is defined as involuntary loss of urine in a socially inappropriate place or time for a child with bladder control, or aged ≥5 years, without neurological damage and with adequate neurological development for age.1,2

Incontinence can be characterized as continuous or intermittent, and diurnal or nocturnal. Continuous UI is more associated with congenital malformations, such as ectopic ureter, while the intermittent type is usually a manifestation of a heterogeneous group of lower urinary tract dysfunctions (LUTDs).3 It is called “daytime urinary incontinence” when it occurs when the child is awake, and “nocturnal enuresis” (NE) when it occurs exclusively during sleep. Patients with intermittent UI when awake as well as during sleep are diagnosed as having daytime UI and NE.2,3

In addition to the social and hygiene impact on the child, voiding dysfunctions significantly affect the quality of life of patients and their families, and can persist beyond childhood.4 LUTD is associated with increased risk of urinary tract infection, delay in vesicoureteral reflux resolution, and loss of renal function.5,6

Directed and detailed anamnesis, the use of a voiding diary, and careful physical examination are essential for the diagnosis, which, in turn, is critical to define the appropriate treatment. The 4-h urine test for infants, uroflowmetry, and ultrasonography (US) are the non-invasive tests that provide relevant diagnostic tools.7,8 However, these data and exams, when performed with inadequate methodology, often result in inconclusive data, leading to the unnecessary indication of invasive urodynamic study for diagnostic clarification, increasing the suffering of the patient and family, as well as the diagnosis time and costs.9

In Brazil, few studies have analyzed the prevalence of daytime UI in children, let alone the diagnostic investigation and treatment of pediatric patients with no evident structural alterations and neurologic abnormalities with daytime UI followed in children's tertiary care centers.10,11

The objective of this study was to characterize a cohort of children with daytime UI without neurological damage followed in a tertiary center, and to verify the concordance between the diagnosis of overactive bladder and its urodynamic manifestation, i.e., detrusor overactivity.

MethodsStudy designA retrospective, descriptive, and analytical study of a cohort of patients whose initial complaint was daytime UI treated at the Urinary Dysfunction Outpatient Clinic of the Instituto da Criança do Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo (ICr/HC-FMUSP), from March of 2000 to December of 2012. The terminology used in this study complied with the standards established in 2006 by the International Children's Continence Society (ICCS) and its 2014 addendum.2,3

Inclusion criteriaPatients with an initial complaint of daytime UI, with or without urinary tract infection, of both genders, aged at least 5 years or with bladder control, with a minimum follow-up period of 6 months were included.

Exclusion criteriaPatients with neurogenic bladder, genetic syndromes, chronic encephalopathy, severe cognitive impairment, urogenital malformations, chronic kidney disease, monosymptomatic NE, and LUTD without UI were excluded from analysis.

Study protocolAll medical records that included the following disease codes were analyzed, according to the 10th edition of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10): R32 (Unspecified UI); R33 (Urinary retention); R39.1 (Other difficulties with micturition); N31 (Neuromuscular dysfunction of bladder, not elsewhere classified); N32 (Other disorders of bladder); and N39 (Other disorders of the urinary tract). Diagnoses were based strictly on medical record information.

A search of the medical records was carried out using a structured protocol,12 and the data were reported in a standardized spreadsheet with 180 variables. The following data were recorded: gender; birth date; date of the initial treatment (T1); anthropometric data; body mass index (BMI) for age; blood pressure; characteristics of urinary incontinence; urinary symptoms, according to criteria of the ICCS 2006 and 2014 (urinary frequency, urinary urgency, urgency incontinence, insensible losses, and postural maneuvers/urinary retention); NE; history of urinary tract infection; bowel habits (constipation and fecal incontinence); physical examination; and voiding diary data. Additional tests were also investigated, such as laboratory tests (urinalysis, urine culture, urine calcium, urea, and creatinine), urinary tract US, uroflowmetry and urodynamics, voiding cystourethrography and renal scintigraphy (99 Dimercaptosuccinic acid-99 Tc-DMSA), treatment, and outcome with cure rate at the first (T1) and final (T2) consultation recorded in the medical chart.

Variables of interestAccording to ICCS criteria, the patient was considered as having “urgency” when the medical records described that he or she reported sudden and unexpected sense of immediate need for urination; “urgency incontinence” when urinary leakage was described as associated with urgency; “urinary retention” if medical records indicated that the patient postponed or suppressed urination by postural maneuvers; “increased urinary frequency” if the patient mentioned more than eight voids per day; and “reduced frequency” when the patient reported three or fewer voids per day.

The patient was considered “constipated” when the medical records mentioned “dry,” “painful” or “hardened stools,” “pain when defecating,” and less than three bowel movements a week, according to the Roma III criteria.13 Patients with previous urinary infection were those whose medical record reported febrile process associated with positive urine culture; recurrent urinary infections were considered when there were three or more cases of urinary infections per year.

Diagnostic investigation: imaging, radiological, and urodynamic testsUS results were analyzed in relation to kidney and bladder morphologies, the presence of spinning top urethra, and the presence of bladder residual volume. The description of trabeculation and/or increased bladder wall thickness >0.3cm was considered a sign of voiding effort and probable bladder filling or emptying dysfunction.2,14 Description of residual urine >20mL or >10% of the expected bladder capacity (EBC, with EBC=[age (years)+1]×30mL in children aged ≤6 years and bladder residue >20mL or >15% of the EBC) in children ≥7 years, was considered pathological and indicative of probable voiding disorder.

The results of free uroflowmetry were recorded according to the curves format. Bell curves were considered normal; tower-shaped curves as characteristic of detrusor overactivity; staccato curves, as dysfunctional urination; intermittent, as hypotonic bladder; and flattened curves, as organic or functional obstruction. Urodynamic studies were performed at the Urology Department of HC-FMUSP using standardized methodology.

The reports of voiding cystourethrography verifying the presence and degree of vesicoureteral reflux (VUR), bladder trabeculation, diverticula, and spinning top urethra were identified. DMSA scintigraphy disclosed the description of renal scars, suggesting loss of kidney function.

TreatmentIn general, treatment was performed through urotherapy, biofeedback, and postural therapy, using laxatives, prophylactic antibiotics, and specific drugs for the treatment of LUTDs (anticholinergics, such as oxybutynin and tolterodine; alpha-blockers, such as doxazosin and tamsulosin; or antidepressants, such as imipramine).

Analysis of diagnostic concordance and predictive value of overactive bladder diagnosis obtained by anamnesis data and noninvasive testsThe diagnosis of overactive bladder, attained through the anamnesis data, was implied in the medical record by: symptoms of urgency and/or urgency incontinence; urinary frequency greater than eight times per day; lack of data on past urinary tract infections; and normal uroflowmetry and ultrasound of the urinary tract, without bladder residual volume, trabeculation, or other alterations. To verify the existence of concordance, this diagnosis was compared to that of detrusor overactivity, obtained through urodynamic study, which is considered the gold standard.15

Evolution and cure rateVoiding symptoms, comorbidities, associated manifestations, and incidence of urinary tract infections in T1 and T2 were assessed to establish the parameters of cure (patient without urinary symptoms), improvement (reduction of at least 50% of voiding symptoms) or unchanged (no improvement in voiding symptoms).2

Statistical analysisDescriptive analysis of continuous and categorical variables was performed. Continuous variables were described by means (±standard deviation). LUTD symptom variables, associated manifestations, and comorbidities in T1 and T2 were analyzed by the nonparametric McNemar test. The concordance between the diagnoses of overactive bladder attained through anamnesis data plus non-invasive examination (US and uroflowmetry) and the diagnosis of detrusor overactivity by invasive urodynamic study – the latter considered to be the gold standard – was compared by Cohen's Kappa coefficient. In all comparisons, were considered significant tests p<0.05.

Ethical aspectsThe study was approved by the Ethics Committee for Research Project Analysis of HC-FMUSP on August 18, 2011 (Protocol 0489/11).

ResultsInitially, 103 patients were included in the study, but 53 did not participate because they did not meet the predetermined inclusion criteria. Of the 50 assessed patients, 43 were females (86.0%). The mean age was 7.9 years. The mean follow-up period of patients attended to at the outpatient clinic was 4.7±3.2 years.

Five patients had a z-score <−1 for BMI for age, 42 had normal weight, and three patients had z-score >+1. Blood pressure <90th percentile was observed in 48 (96.0%) patients; two patients had blood pressure between p90% and p95%, and had their blood pressure levels normalized during follow-up.

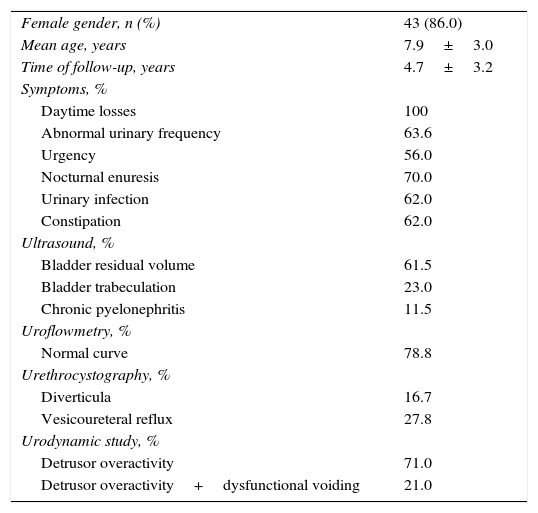

All patients reported loss of urine. A total of 24 (48.0%) patients reported urinary incontinence and urgency incontinence episodes; 22 (44.0%) reported daytime urinary incontinence; and four (8.0%) characterized their losses as urgency incontinence episodes only. The main symptoms of LUTD described in the initial anamnesis were urgency (n=28; 56.0%), urgency incontinence (n=28; 56.0%), and urinary retention (n=4; 8.0%). The main comorbidities were: urinary tract infections (n=31; 62.0%), NE (n=35; 70.0%), constipation (n=31; 62.0%), and fecal loss (n=8; 16.0%), as shown in Table 1.

Demographic data, clinical results, and laboratory tests of a cohort of 50 children with functional daytime urinary incontinence treated at a tertiary service.

| Female gender, n (%) | 43 (86.0) |

| Mean age, years | 7.9±3.0 |

| Time of follow-up, years | 4.7±3.2 |

| Symptoms, % | |

| Daytime losses | 100 |

| Abnormal urinary frequency | 63.6 |

| Urgency | 56.0 |

| Nocturnal enuresis | 70.0 |

| Urinary infection | 62.0 |

| Constipation | 62.0 |

| Ultrasound, % | |

| Bladder residual volume | 61.5 |

| Bladder trabeculation | 23.0 |

| Chronic pyelonephritis | 11.5 |

| Uroflowmetry, % | |

| Normal curve | 78.8 |

| Urethrocystography, % | |

| Diverticula | 16.7 |

| Vesicoureteral reflux | 27.8 |

| Urodynamic study, % | |

| Detrusor overactivity | 71.0 |

| Detrusor overactivity+dysfunctional voiding | 21.0 |

A voiding diary was completed by 33 (66.0%) patients, of whom 21 (63.6%) had increased urinary frequency>eight times a day. Six (18.2%) patients had NE and four (12.1%) reported loss of urine.

In T1, urinary tract US was performed in 49 (98.0%) patients, disclosing post-voiding residual volume in 16 (61.5%) patients, bladder thickening in six (23.0%), and unilateral chronic pyelonephritis in three (11.5%).

Voiding cystourethrography was performed in 36 (72.0%) children. Of these, 18 (50.0%) showed some abnormality: unilateral vesicoureteral reflux (n=3; 16.7%); bilateral VUR (n=2; 11.1%), with four (80.0%) of the five VUR patients showing VUR degree ≥III; trabecular bladder (n=12; 11.1%); diverticula (n=3; 16.7%); and spinning top urethra (n=3; 16.7%). Some patients had more than one anatomical alteration, as shown in Table 1.

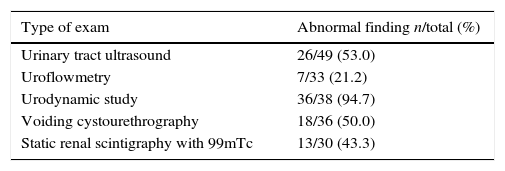

Free uroflowmetry was performed in 33 patients, and it was described as normal in 26 (78.8%). Among patients submitted to the urodynamic study, 36 (94.7%) had urodynamic alterations, namely: detrusor overactivity in 27 (71.0%), detrusor overactivity and dysfunctional voiding in eight (21.0%), and dysfunctional voiding in one (2.7%); two patients had normal results. The incidence of abnormal imaging tests, uroflowmetry, urodynamics, and renal scintigraphy is shown in Table 2.

Compilation of the abnormal results of imaging tests, uroflowmetry, and urodynamic study in a cohort of 50 children with functional daytime urinary incontinence treated at a tertiary service.

| Type of exam | Abnormal finding n/total (%) |

|---|---|

| Urinary tract ultrasound | 26/49 (53.0) |

| Uroflowmetry | 7/33 (21.2) |

| Urodynamic study | 36/38 (94.7) |

| Voiding cystourethrography | 18/36 (50.0) |

| Static renal scintigraphy with 99mTc | 13/30 (43.3) |

All 50 patients underwent urotherapy, four underwent physical postural therapy, and four others, biofeedback.

The prescribed drug treatments included oxybutynin (anticholinergic) to 28 (56%) patients; doxazosin (alpha-blocker) to three (6.0%); tamsulosin (alpha-blocker) to one (2.0%); association of oxybutynin and tamsulosin to one (2.0%); and imipramine (antidepressant) to one patient (2.0%). Twelve patients (24.0%) showed irregular adherence to treatment. The mean time of anticholinergic use was 2.9 years (±2.30), and for alpha-blockers, 1.3 years (±0.58). Lactulose was prescribed to 12 (24.0%) patients with constipation. Prophylactic antibiotics were prescribed to 25 (50.0%) patients with recurrent urinary tract infections. The mean period of prophylactic antibiotic use was 2.5 years (±1.52).

There was a clear reduction in complaints from T1 to T2, which decreased from 100% to 32.0%. The evolution regarding cure, improvement, or persistence of LUTD symptoms after treatment (T2) is shown in Fig. 1. Fig. 2 shows the evolution of the incidence of urinary tract infections.

Regarding the voiding symptoms of LUTD, 68% of patients showed improvement or cure.

An 85% concordance was found between the diagnosis of overactive bladder obtained by anamnesis and noninvasive exams (US and free uroflowmetry) and the diagnosis of detrusor overactivity obtained by urodynamic study with Cohen's kappa coefficient, with p<0.05.

DiscussionThe analysis of this group of patients showed a prevalence of the female gender, mean age at start of treatment of 7 years, long follow-up period (4.7±3.2 years), high incidence of urinary symptoms, NE, constipation and fecal incontinence, UTI, UTI recurrence, urological abnormalities, and kidney lesions.

The most prevalent LUTD in this study was overactive bladder and its urodynamic manifestation, i.e., detrusor overactivity. It was verified, similarly to other studies, that a percentage of patients treated at tertiary services achieve cure; others show improvement, but become dependent on medication; and approximately 30% are refractory to treatment – a group that could reach adulthood with LUTD.16,17 A concordance of 85% through Cohen's kappa coefficient, with p<0.05, was also observed for the diagnosis of overactive bladder, with anamnesis data and noninvasive tests, and the diagnosis of detrusor overactivity obtained by urodynamic study.

It is difficult to calculate the exact prevalence of UI, as most studies use different methodological strategies and do not always use the ICCS terminology.3,18

The nutritional classification of the patients in the present study showed that 96.0% had normal weight and 4.0% were overweight, which does not confirm the literature data that describes a positive association between obesity and LUTD in children.19

In the assessed cohort, the manifestation of NE was 70.0%, i.e., a much higher value than that described in the general pediatric population, which is 7.5%, demonstrating the frequent association of this entity with daytime urinary loss.20

The prevalence of constipation in healthy children ranges from 0.7% to 29.6% and may affect up to 50% of those with LUTD.21 Studies on the subject have shown that 10.0% of constipated children have UTI and 30.0%, daytime UI. The prevalence of 62.0% constipation demonstrated in this study was similar to that described by Veiga et al.,22 which was 54.9% in a Brazilian study with children with UI caused by overactive bladder. It is believed that the prevalence of constipation in children is underestimated, because most parents do not have such information, and the children, without the use of tools such as the Bristol scale, give poor reports about its occurrence.

The prevalence of UTI in this study was 62.0%, i.e. much higher than that in the general pediatric population (11.0%), but similar to that found in children with UI, described in up to 50.0% of patients.23

Urodynamics were performed in 76.0% of patients in this study; they were altered in 94.7% of cases, and detrusor overactivity was present in 71.0% of cases, representing the most prevalent urodynamic diagnosis, consistent with literature data.3

Regarding the prevalence of gender, age, follow-up period, urinary symptoms, incidence of UTIs, the frequency of association with VUR, and the cure rate, the results of this study were similar to studies published in tertiary services, considering the previously mentioned limitations.17,24,25

For overactive bladder, the analysis of diagnostic concordance between the clinical diagnosis obtained by anamnesis, with investigation of the presence of urgency and/or urgency incontinence symptoms and increased urinary frequency, with no history of urinary tract infections and normal non-invasive tests, and the diagnosis of detrusor overactivity at the urodynamic study showed 85.0% concordance through Cohen's kappa coefficient, with p<0.05. The diagnosis of dysfunctional voiding does not allow this analysis; the diagnosis of dysfunctional voiding can only be defined by the presence of the staccato curve in the uroflowmetry with electromyography, or by urodynamic study.3 In literature, only two other studies performed this type of analysis: Ramamurthy et al.25 described a concordance between the diagnosis of overactive bladder by anamnesis and noninvasive tests, with sensitivity of 88.4% and specificity of 72.7% when compared to the urodynamic diagnosis of detrusor overactivity; while Bael et al.15 conducted a prospective multicenter study in 151 children with LUTD, obtaining inconclusive results. In the latter study, there was a concordance of only 33% between the diagnoses of overactive bladder and detrusor overactivity in the urodynamic study; the authors highlight the fact that most of the included patients were diagnosed with dysfunctional voiding, an incidence that, according to the authors, did not represent the typical sample of the service.

The evolution of the therapeutic response in UI in this study was cure in 36% of patients, and improvement (decrease of at least 50% of complaints) in 32% of patients who continued using the medication. These results are comparable to those obtained by Glad Mattson et al.,16 achieved in a tertiary hospital.

The limitations of this study were those related to a retrospective study, with difficulties arising from inaccurate notes in medical records, multiple observers following the patient, as well as temporal variations in institutional availability of human and technical resources.26

The present study found, in this group of patients, high prevalence of voiding symptoms, urinary infections, urological abnormalities, kidney lesions, and poorer cure rate, suggesting that this subgroup of patients could have a different pathogenesis when compared to patients with non-neurological daytime UI, studied in large groups of schoolchildren or in general outpatient clinics.

The initial clinical diagnosis should result from the sum of the clinical variables and noninvasive tests. The diagnosis of overactive bladder represents a syndromic diagnosis and could justify the start of the treatment, after assessment of suggestive clinical history, normal physical examination, negative history of UTI, and normal non-invasive test results.27 The urodynamic test should be indicated in patients with symptoms of overactive bladder refractory to treatment, as well as those patients in whom an organic cause is suspected during the diagnostic investigation.28 The use of such conduct, including in tertiary services, could result in a decrease in the number of invasive procedures, reducing the discomfort of the patient and family, time until the start of the treatment, and hospital costs.29

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Lebl A, Fagundes SN, Koch VH. Clinical course of a cohort of children with non-neurogenic daytime urinary incontinence symptoms followed at a tertiary center. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2016;92:129–35.

Study conducted at the Pediatric Nephrology Outpatient Clinic, Instituto da Criança, Hospital das Clínicas, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de São Paulo (USP), São Paulo, SP, Brazil.