To compare the behavior of preterm newborns and full-term newborns using the Newborn Behavioral Observation and to evaluate the mothers’ experience when participating in this observation.

MethodThis was a cross-sectional study performed at a referral hospital for high-risk births, involving mothers and neonates before hospital discharge. The mothers answered the sociodemographic questionnaire, participated in the Newborn Behavioral Observation session, and evaluated the experience by answering the parents’ questionnaire at the end. The characteristics of the preterm newborn and full-term newborn groups and the autonomic, motor, organization of states, and responsiveness scores were compared. Linear regression was performed to test the association of the characteristics of mothers and neonates with the scores in the autonomic, motor, organization of states, and responsiveness domains.

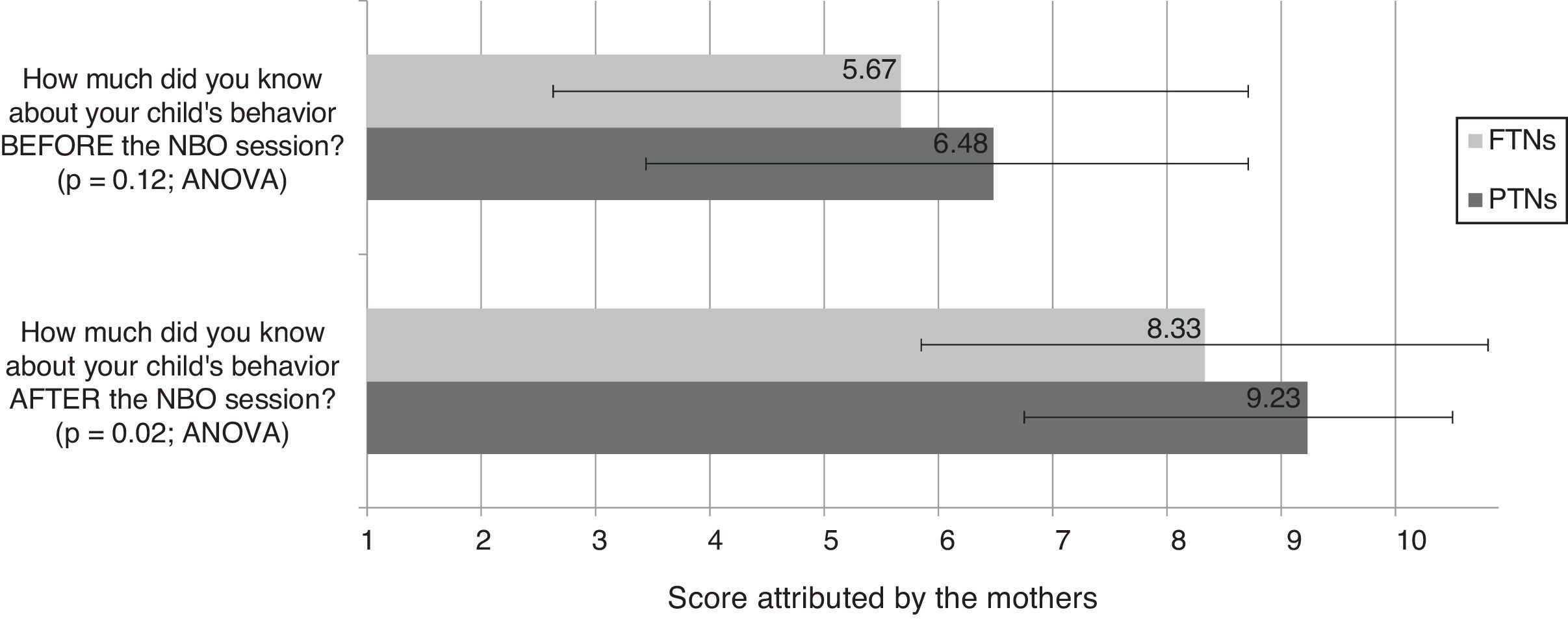

ResultsThe Newborn Behavioral Observation was performed with 170 newborns (eight twins and 77% preterm newborns). Approximately 15% of the mothers were adolescents and had nine years of schooling, on average. The groups differed regarding weight for gestational age, age at observation, APGAR score, feeding, and primiparity. The linear regression adjusted for these variables showed that only prematurity remained associated with differences in the scores of the motor (p=0.002) and responsiveness (p=0.02) domains. No statistical difference was observed between the groups in the score attributed to one's own knowledge prior to the session (p=0.10). After the session, these means increased in both groups. This increase was significantly higher in the preterm newborn group (p=0.02).

ConclusionsThe Newborn Behavioral Observation increased the mothers’ knowledge about the behavior of their children, especially in mothers of preterm newborns, and identified differences in the behavior of preterm newborns and full-term newborns regarding the motor and responsiveness domains.

Comparar o comportamento de recém-nascidos pré-termo e a termo utilizando a Newborn Behavioral Observation e avaliar a experiência das mães em participar desta observação.

MétodoEstudo transversal realizado em hospital de referência para partos de risco, envolvendo mães e neonatos antes da alta hospitalar. As mães responderam ao questionário sociodemográfico, participaram da sessão de Newborn Behavioral Observation e ao final avaliaram a experiência respondendo ao questionário de pais. As características dos grupos de recém-nascidos pré-termo e recém-nascidos termo e os escores dos domínios autonômico, motor, organização dos estados e responsividade foram comparados. Realizou-se regressão linear para testar a associação de características das mães e neonatos com os escores nos domínios autonômico, motor, organizac¸ão dos estados e responsividade.

ResultadosA Newborn Behavioral Observation foi realizada com 170 recém-nascidos (oito gemelares e 77% pré-termo). Cerca de 15% das mães eram adolescentes e estudaram em média por 9 anos. Os grupos difereriram quanto ao peso para idade gestacional, idade na observação, APGAR, alimentação e primiparidade. A regressão linear ajustada para estas variáveis mostrou que apenas a prematuridade manteve-se associada a diferenças nos escores dos domínios Motor (p=0,002) e responsividade (p=0,02). Não houve diferença estatística entre os grupos na pontuação atribuída ao próprio conhecimento antes da sessão (p=0,10). Após a sessão estas médias subiram em ambos os grupos. Este aumento foi significativamente maior no grupo de recém-nascidos pré-termo (p=0,02).

ConclusõesA Newborn Behavioral Observation aumentou o conhecimento das mães sobre o comportamento dos filhos, principalmente para as mães de recém-nascidos pré-termo, e identificou diferenças no comportamento de recém-nascidos pré-termo e recém-nascidos termo nos domínios motor e responsividade.

Advances in neonatal intensive care have increased the chances of survival of newborns at risk, reinforcing the need to monitor their abilities and skills in the long term.1 Consistent with a concept of the newborn as a passive being, who only reacted to environmental stimuli, the traditional assessment was based primarily on the physical examination, Apgar score, the so-called “primitive reflexes,” and neurological evolution.2 However, in the 1970s, new perspectives for the observation and understanding of child development emerged, based on the recognition of the rich variety of behaviors used by newborns to express their abilities and needs.3,4

Brazelton was one of the first to describe the repertoire of newborns’ interacting abilities and their capacity to select stimuli, recognizing the newborn as a competent being, who gives signs that guide the parents’ attitudes and contribute to establish the affective bond.2 Brazelton drew attention to the delicate balance between the physiological regulation systems, motor organization and alertness states, which provide support to the newborn's maintenance of attention and social interaction. Based on these premises, he created a neonatal behavior assessment system called the Neonatal Behavioral Assessment Scale (NBAS),2 which allows mapping the newborn's ability to self-regulate and maintain effective social interactions.

Recently, the Newborn Behavioral Observation (NBO) system was created, being a simpler tool that maintained the conceptual richness of the NBAS, but shifting the focus from the diagnosis of disorders to the observation of the newborn's potentials and individuality. It is a family-centered resource, designed to describe the skills of the newborn, explicitly aiming to strengthen the relationship between parents and their children and to promote the development of a supportive relationship between professionals and families.5

Considering that the neonatal period is critical for the child's adaptation to the new environment and that parents also undergo a transition in their relationship with the new child, the opportunity to better understand the neonatal behavior provided by the NBO has an interventional aspect, as it helps to strengthen the reciprocal relations between the newborn and the parents, which may have long-term effects.6

Studies on the NBO are still scarce; however, there is evidence that this approach contributes to a better understanding of the NB by parents and professionals7,8; better interaction with parents9; increase in the healthcare professional's confidence in the care provided and in their ability to work with at-risk newborns.10 The NBO is also associated with reduced signs of postpartum depression11 and facilitates the transition to the maternal role.12

Because this is a brief and easy-to-apply scale, it can be used in different contexts, such as neonatal intensive care units (NICUs),6 rooming-in,5 home care, and early intervention programs.13,14 The focus on strengthening the mother–child relationship, as well as the effects on professional confidence,8–10 make the NBO a powerful resource to stimulate good practices in the care of healthy newborns, especially those at risk, and can be very useful in maternal and child care in Brazil.

The aims of this study were to compare the behavior of preterm newborn (PTN) and full-term newborn (FTN) using the NBO system and to evaluate the maternal experience when participating in this observation.

MethodThis was a cross-sectional study that analyzed the behavior of newborns using the NBO. The convenience sample consisted of all the newborns and their mothers admitted to the Casa do Bebê of Hospital Sofia Feldman (HSF) between May and October 2015 who agreed to participate in the study. HSF (Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil) is a regional referral hospital for at-risk births by the Brazilian Unified Health System. The hospital performs 900 deliveries per month, and approximately 14% are considered at risk. The Casa do Bebê receives approximately 40 newborns per month to monitor weight gain and provide phototherapy and antibiotic therapy until hospital discharge. The following are requirements for admission to Casa do Bebê: corrected gestational age (CGA)>34 weeks, weight>1500g, ascending weight curve for at least two days, and infant without catheter or peripheral devices.

During the data collection period, 270 infants were admitted to Casa do Bebê, of whom 16 were excluded due to genetic, neurological, and motor diseases, and/or sensory deficits previously diagnosed in the neonatal unit routines. A total of 84 mothers refused to participate or could not be observed prior to discharge. The length of stay at Casa do Bebê ranged from three to seven days.

The NBO consists of 18 behavioral and reflex items, divided into four dimensions represented by the acronym AMOR: (A) autonomic system – skin color, respiratory pattern, visceral function; (M) motor system – tonus of arms, legs, shoulder and neck, activity level, and sucking, rooting, and hand grasping reflexes; (O) organization of alertness states – capacity for habituation and sleep preservation, crying, consolability, and transition between alertness states; (R) responsiveness – ability to respond and interact with people and objects with visual and auditory stimuli.

All items are scored on a three-point scale, with one point being assigned to weak (weak neck tonus, for instance) or altered responses (very intense stress signals, for instance), two points to transition behaviors, and three to well-established behaviors (easy habituation to light and sound, for instance).5

The observation is made with the use of a rattle, a red ball, and a flashlight; the procedure takes approximately 10min and can be performed up to the corrected age of three months.5 The NBO was performed with one dyad at a time, in the room where they were admitted, between feedings. The sleep and wakefulness states were evaluated at the beginning of the observation, according to the criteria established by the NBO authors. Procedures for habituation to light and sounds were performed only when the child was in a light or deep sleep.15

The NBO also includes a questionnaire for parents, in which they assess the effectiveness of the NBO in helping them understand their baby's behavior.6 This questionnaire is divided into two parts: the first three questions address parental knowledge on neonatal behavior, and the other three, the experience with the NBO session. Items are scored on a four-point Likert scale (“a lot,” “enough,” “little,” and “nothing”). Questions that address the parents’ knowledge about child behavior before and after the NBO are scored on a scale of “1” (little) to “10” (a lot).15

All NBO components were cross-culturally adapted to the Brazilian Portuguese language.16 Data were collected by eight professionals trained by professionals from the Brazelton Institute (Boston, MA, United States) and received a certification authorizing the application of the NBO. To standardize the procedures, extra training was performed, with joint analysis and scoring of NBO videos, where each item was discussed by the entire team, which served as the basis for the creation of a standardized technical observation procedure and more specific criteria to score the items that generated doubt among the researchers.

As described in the NBO manual, the professional started the session by explaining to the mothers that the NBO is not a diagnostic test, does not identify pathological or atypical signs, but it is an approach based on the newborn's skills at that moment. It is an observation used to help parents recognize the behaviors and identify the strategies of care that best fit their baby's needs.5 The mothers were invited to participate as partners in the observation; during the session the professional praised the mothers’ previous knowledge and allowed them to clarify doubts and express their concerns. At the end of the session, the mother and the professional discussed the observed behaviors, identifying strengths and areas where the newborn needed support. The mother then answered the NBO parents’ questionnaire, assessing her experience during the session.

A structured questionnaire was also used to characterize the perinatal and sociodemographic conditions of the family, in addition to the Brazilian Economic Classification Criteria.17

Data were organized using the Excel software (Microsoft®, version 14.5.2, WA, USA) and analyzed using SPSS (Released 2010. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 19.0, NY, USA). The Mann–Whitney and chi-squared tests were used to compare the groups. The Mann–Whitney test was also used to compare the behavior of infants in the four AMOR domains and the responses of the parents’ questionnaire. Responses on mothers’ knowledge about neonatal behavior before and after the observation were compared using the ANOVA test. A significance level of 5% was used for all analyses.

A multiple linear regression was performed to test the association of characteristics of the mothers and neonates with the median scores in the AMOR domains. The variables with p<0.20 in the univariate analysis were included in the initial model of each domain. Variables were excluded one by one, through the backward-stepwise method, until all variables in the model presented a p-value<0.05.

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (CAAE n. 29437514.1.0000.5149). All the mothers included in the study signed the informed consent form before the beginning of the procedures.

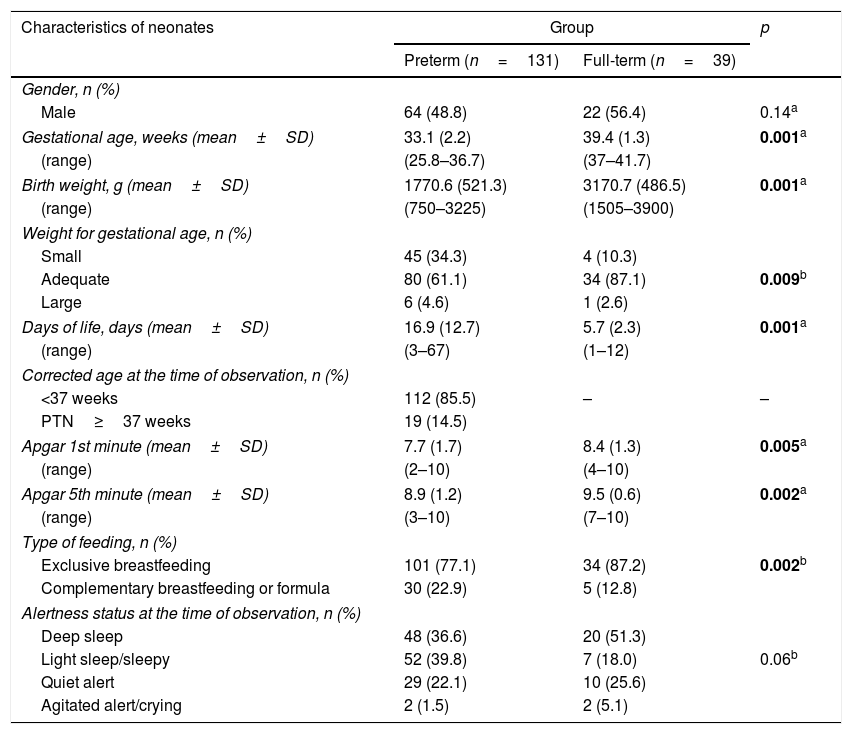

ResultsThe NBO was carried out with 170 newborns and 162 mothers (eight twins). The characteristics of newborns and mothers are shown in Table 1. Approximately 77% of sample consisted of PTNs; most babies had adequate birth weight for gestational age and were exclusively breastfed at the time of the observation. The PTNs were assessed on average at 17 days of age and the FTNs, at 5.7 days (p=0.001); 15% of the PTNs had reached 37 weeks of CGA at the time of the observation. Most families (81.8%) belonged to the lowest economical classes (C, D/E).18 The mothers had on average nine years of schooling, and 17.7% of the PTN's mothers and 5.1% of the FTN's mothers were adolescents (p=0.09). Primiparous mothers accounted for 59.8% and 40% of the PTN and FTN groups, respectively (p=0.04).

Characteristics of neonates and mothers of the preterm and full-term groups.

| Characteristics of neonates | Group | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preterm (n=131) | Full-term (n=39) | ||

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Male | 64 (48.8) | 22 (56.4) | 0.14a |

| Gestational age, weeks (mean±SD) | 33.1 (2.2) | 39.4 (1.3) | 0.001a |

| (range) | (25.8–36.7) | (37–41.7) | |

| Birth weight, g (mean±SD) | 1770.6 (521.3) | 3170.7 (486.5) | 0.001a |

| (range) | (750–3225) | (1505–3900) | |

| Weight for gestational age, n (%) | |||

| Small | 45 (34.3) | 4 (10.3) | |

| Adequate | 80 (61.1) | 34 (87.1) | 0.009b |

| Large | 6 (4.6) | 1 (2.6) | |

| Days of life, days (mean±SD) | 16.9 (12.7) | 5.7 (2.3) | 0.001a |

| (range) | (3–67) | (1–12) | |

| Corrected age at the time of observation, n (%) | |||

| <37 weeks | 112 (85.5) | – | – |

| PTN≥37 weeks | 19 (14.5) | ||

| Apgar 1st minute (mean±SD) | 7.7 (1.7) | 8.4 (1.3) | 0.005a |

| (range) | (2–10) | (4–10) | |

| Apgar 5th minute (mean±SD) | 8.9 (1.2) | 9.5 (0.6) | 0.002a |

| (range) | (3–10) | (7–10) | |

| Type of feeding, n (%) | |||

| Exclusive breastfeeding | 101 (77.1) | 34 (87.2) | 0.002b |

| Complementary breastfeeding or formula | 30 (22.9) | 5 (12.8) | |

| Alertness status at the time of observation, n (%) | |||

| Deep sleep | 48 (36.6) | 20 (51.3) | |

| Light sleep/sleepy | 52 (39.8) | 7 (18.0) | 0.06b |

| Quiet alert | 29 (22.1) | 10 (25.6) | |

| Agitated alert/crying | 2 (1.5) | 2 (5.1) | |

| Characteristics of mothers | Group | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preterm (n=123) | Full-term (n=39) | ||

| Age, n (%) | |||

| <19 years | 22 (17.7) | 2 (5.1) | 0.09b |

| Years of study, years (mean±SD) | 9.4 (2.9) | 9.3 (2.7) | 0.52a |

| (range) | (2–18) | (4–16) | |

| Marital status, n (%)c | |||

| Married or common-law marriage | 69 (57.0) | 23 (62.1) | 0.33b |

| Divorced, separated or single | 52 (42.9) | 14 (37.8) | |

| Economic Classification Criteria, n (%)d | |||

| A+B | 21 (17.1) | 5 (13.2) | 0.26b |

| C+D/E | 84 (82.9) | 33 (86.8) | |

| Parity, n (%) | |||

| Primiparous | 73 (59.8) | 16 (40.0) | 0.04b |

n, sample size; SD, standard deviation.

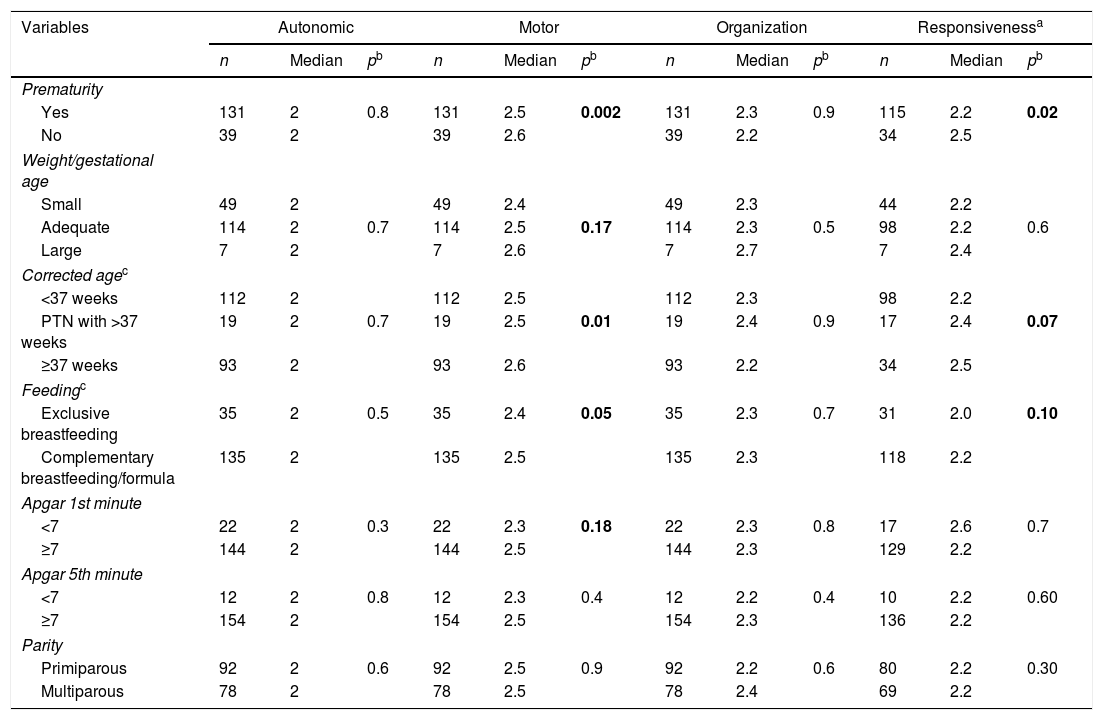

Table 2 shows the comparison of the medians of scores in the AMOR domains regarding gestational age, weight-for-age classification, CGA, and feeding at the time of observation, Apgar score at the 1st and 5th minutes, and parity. No statistically significant differences were observed between these variables and the median scores of the autonomic and organization of states domains.

Comparison between the medians of the scores in the autonomic, motor, organization of states and responsiveness (AMOR) domains of the Newborn Behavioral Observation (NBO).

| Variables | Autonomic | Motor | Organization | Responsivenessa | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Median | pb | n | Median | pb | n | Median | pb | n | Median | pb | |

| Prematurity | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 131 | 2 | 0.8 | 131 | 2.5 | 0.002 | 131 | 2.3 | 0.9 | 115 | 2.2 | 0.02 |

| No | 39 | 2 | 39 | 2.6 | 39 | 2.2 | 34 | 2.5 | ||||

| Weight/gestational age | ||||||||||||

| Small | 49 | 2 | 49 | 2.4 | 49 | 2.3 | 44 | 2.2 | ||||

| Adequate | 114 | 2 | 0.7 | 114 | 2.5 | 0.17 | 114 | 2.3 | 0.5 | 98 | 2.2 | 0.6 |

| Large | 7 | 2 | 7 | 2.6 | 7 | 2.7 | 7 | 2.4 | ||||

| Corrected agec | ||||||||||||

| <37 weeks | 112 | 2 | 112 | 2.5 | 112 | 2.3 | 98 | 2.2 | ||||

| PTN with >37 weeks | 19 | 2 | 0.7 | 19 | 2.5 | 0.01 | 19 | 2.4 | 0.9 | 17 | 2.4 | 0.07 |

| ≥37 weeks | 93 | 2 | 93 | 2.6 | 93 | 2.2 | 34 | 2.5 | ||||

| Feedingc | ||||||||||||

| Exclusive breastfeeding | 35 | 2 | 0.5 | 35 | 2.4 | 0.05 | 35 | 2.3 | 0.7 | 31 | 2.0 | 0.10 |

| Complementary breastfeeding/formula | 135 | 2 | 135 | 2.5 | 135 | 2.3 | 118 | 2.2 | ||||

| Apgar 1st minute | ||||||||||||

| <7 | 22 | 2 | 0.3 | 22 | 2.3 | 0.18 | 22 | 2.3 | 0.8 | 17 | 2.6 | 0.7 |

| ≥7 | 144 | 2 | 144 | 2.5 | 144 | 2.3 | 129 | 2.2 | ||||

| Apgar 5th minute | ||||||||||||

| <7 | 12 | 2 | 0.8 | 12 | 2.3 | 0.4 | 12 | 2.2 | 0.4 | 10 | 2.2 | 0.60 |

| ≥7 | 154 | 2 | 154 | 2.5 | 154 | 2.3 | 136 | 2.2 | ||||

| Parity | ||||||||||||

| Primiparous | 92 | 2 | 0.6 | 92 | 2.5 | 0.9 | 92 | 2.2 | 0.6 | 80 | 2.2 | 0.30 |

| Multiparous | 78 | 2 | 78 | 2.5 | 78 | 2.4 | 69 | 2.2 | ||||

PTN, pre-term newborn. In bold, the variables with p<0.20, included in the initial linear regression model in each domain.

The final multiple linear regression model showed that only the variable prematurity was associated with differences in the mean scores of the motor and responsiveness domains (p=0.002 and p=0.06, respectively). The PTNs presented lower medians than the FTNs. It was not possible to observe the responsiveness items in 21 (12.4%) children, because they were too sleepy or irritated at the time of the observation.

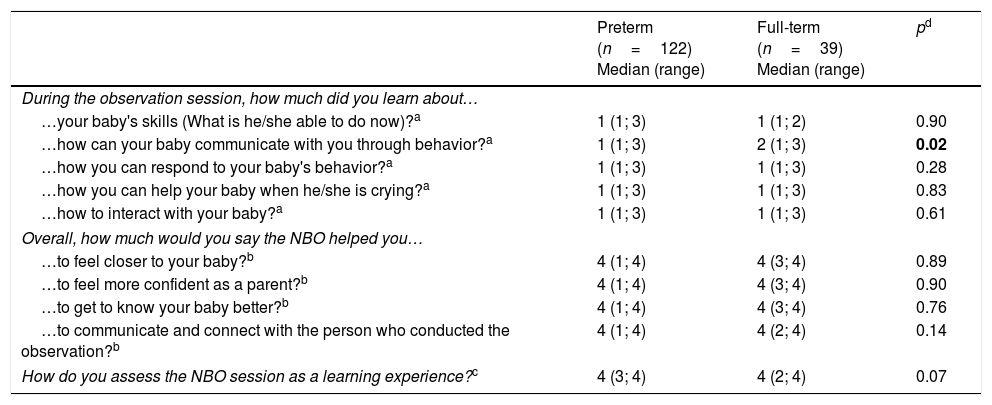

Table 3 shows the comparison of answers of mothers of PTNs and FTNs to the questions in the parents’ questionnaire. The mothers reported that the NBO helped them “a lot”/“enough” to feel more confident as mothers and to get to know the baby better, to feel closer to their child, to learn about their child's abilities, how to respond and interact with their child, and about how the newborn communicates through behavior. In this last question, the “a lot” responses of the mothers of PTNs were higher than those of the FTNs (p=0.02).

Analysis of the mothers’ perception of the Newborn Behavioral Observation (NBO) session's contribution to the relationship with their babies and with healthcare professionals, considering preterm and full-term babies.

| Preterm (n=122) Median (range) | Full-term (n=39) Median (range) | pd | |

|---|---|---|---|

| During the observation session, how much did you learn about… | |||

| …your baby's skills (What is he/she able to do now)?a | 1 (1; 3) | 1 (1; 2) | 0.90 |

| …how can your baby communicate with you through behavior?a | 1 (1; 3) | 2 (1; 3) | 0.02 |

| …how you can respond to your baby's behavior?a | 1 (1; 3) | 1 (1; 3) | 0.28 |

| …how you can help your baby when he/she is crying?a | 1 (1; 3) | 1 (1; 3) | 0.83 |

| …how to interact with your baby?a | 1 (1; 3) | 1 (1; 3) | 0.61 |

| Overall, how much would you say the NBO helped you… | |||

| …to feel closer to your baby?b | 4 (1; 4) | 4 (3; 4) | 0.89 |

| …to feel more confident as a parent?b | 4 (1; 4) | 4 (3; 4) | 0.90 |

| …to get to know your baby better?b | 4 (1; 4) | 4 (3; 4) | 0.76 |

| …to communicate and connect with the person who conducted the observation?b | 4 (1; 4) | 4 (2; 4) | 0.14 |

| How do you assess the NBO session as a learning experience?c | 4 (3; 4) | 4 (2; 4) | 0.07 |

Questions answered on a 4-point Likert scale, with 1 corresponding to a lot; 2, enough; 3, little; 4, nothing.

Questions answered on a 4-point Likert scale, with 1 corresponding to very little; 2, a little; 3, enough; 4, a lot.

Fig. 1 shows the comparative analysis of the perception of mothers of PTNs and FTNs about their knowledge on the baby's behavior before and after the NBO session. On a scale of 0–10, the mean score attributed to the knowledge prior to the session was 5.68±3.04 and 6.48±2.48 for the mothers of FTNs and PTNs, respectively (p=0.10). After the session, these means increased to 8.33±2.23 and 9.23±1.27, respectively (p=0.02). When comparing the variation of means within the groups, it was observed that the scores increased significantly after the NBO session in both groups (p<0.001).

DiscussionThe NBO managed to capture differences in the behavior of PTNs and FTNs. Furthermore, the observation of neonatal behavior was welcomed by the mothers. Although it is not a test, the NBO was able to identify variations in neonatal behavior according to the newborns’ gestational age. Using the NBAS, a scale that preceded the NBO, Wolf et al.19 observed that very low-birth weight PTNs had a different behavior from FTNs in all NBAS domains (orientation, motor, organization state, state regulation, autonomic stability), except for reflexes and habituation, which were not assessed.

In this study, the NBO captured differences in the newborns’ behavior in the motor and responsiveness areas. PTNs have their own tonus and reflex response patterns20 and have more difficulties in personal-social interactions than the FTNs, as documented in the literature.21 However, interaction with the observer and ability to follow objects, which are responsiveness items, may have been affected by the poorer motor control of PTNs, resulting in lower scores in this domain. This result did not change when other variables such as weight for gestational age, CGA, feeding at the time of observation, Apgar score, and parity were included in the analysis.

The PTNs had three times as many days of life as the FTNs, being thus better adapted to the extrauterine life, to the noises and illumination of the environment, which may have affected the responses in the domains of autonomic control (A) and organization of alertness states (O), corroborating the findings of Garcia et al.22 using the NBAS. Even considering intervening variables such as weight for gestational age and CGA at the moment of the observation, the behavior of the PTNs was not different from the FTNs regarding the regulation of stress symptoms (skin color and respiration, among others) and the organization of alertness states (preservation of sleep and clear transition between sleep and wakefulness, among others).

The approach proposed by the NBO was well appraised by the mothers and represented a significant gain of knowledge for the two groups, being more relevant for the mothers of the PTNs. The mothers of the present study reported lower baseline knowledge than that reported by Fishman et al.,15 which can be explained by the higher proportion of primiparous mothers in the PTN group and the specificities of premature birth. For these mothers, the NBO possibly provided an opportunity to observe the potentialities of the preterm baby, often masked by the fragile appearance and clinical complications. These results highlight the importance of using the NBO with mothers and at-risk infants.

A similar finding was observed in another study, where maternal reports indicated that the NBO was effective in increasing knowledge about behavior and how to respond and interact with the newborns.7 Cheetham and Hanssen12 observed an increase in maternal sense of competence and confidence when facing the challenges of motherhood, considering the NBO as a strategic resource to improve the transition to motherhood, to provide support in early family life, and as postpartum support. Kashiwabara23 concluded that the NBO provided an opportunity for parents to get to know their children better and to establish closer ties with them.

The NBO is an observation system designed to describe the newborn's abilities and individuality, to foster the relationship between the parents and the baby, and to promote the development of a supportive relationship between the family and the professional.5,18,24 These characteristics appear to be especially useful for mothers of PTNs when facing the preterm infant's needs and the parental stress associated with prematurity.5,6,24 The satisfaction shown by mothers of PTNs is a strong incentive to continue using this strategy in the health services routine.24

The NBO has also been used in maternities and NICUs,6,24 as well as in home visits.8,10,25 McManus and Nugent8 state that parents who participated in an early intervention program based on the NBO better evaluated the received care regarding facilitation of parent–child interaction than the control group, which received the usual early intervention care. Holland and Watkins,25 when evaluating the professionals’ perceptions, found that the implementation of the NBO in home visits improved the relationship between parents and their newborns.

In this first Brazilian study, the NBO was used in the context of Casa do Bebê, being included into the care and guidance routines offered to mothers as part of the preparation for hospital discharge. This proposal is aligned with what is recommended by the Brazilian Policy of Humanized Care for the Newborn,1 which aims to improve the quality of the newborn's neurobehavioral and psycho-affective development and favor the maternal–infant bond.

The NBO was successfully incorporated into public policies in other countries,13,14 such as the United Kingdom, whose health system recommends the use of the NBO and NBAS in early intervention programs.13 In Brazil, in addition to being incorporated into the services that use the kangaroo method, the NBO can be strategic in follow-up programs, especially with families at social and biological risk, as well as in home visits in primary care.

The NBO is an unique experience that depends on the examiner's sensitivity and the timing of the mother–child dyad,5 for which reliability measures are not pertinent. Aiming to reduce this limitation, the training was thorough, the professionals were certified by the Brazelton Institute, and the procedures and behaviors were standardized with the entire team. The discrepancy between the number of PTNs and FTNs reflects the patients treated at Casa do Bebê, whose target audience is PTNs being prepared for discharge, but eventually treating FTNs for phototherapy and/or antibiotic therapy.

NBO is a simple and feasible tool that identified differences in the behavioral patterns during the first days of life of PTNs and FTNs regarding the motor and responsiveness domains. The NBO was effective in increasing maternal knowledge of their children's behavior. However, it is important to investigate whether this has an impact on long-term parental bond, reduction of maternal depression and parental stress, and acceptance by families from other social extracts. It is expected that these results will stimulate further studies and contribute to a wider use of the NBO in maternal and child healthcare services as a strategy for strengthening mother-infant and family-health professional ties.

FundingCAPES, CNPq, and Grand Challenges Canada.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

To the Projeto Cuidar e Crescer Juntos team, who contributed with data collection and to the families who participated in this study.

To CAPES, CNPQ, and Grand Challenges Canada for the financial support.

Please cite this article as: Guimarães MA, Alves CR, Cardoso AA, Penido MG, Magalhães LC. Clinical application of the Newborn Behavioral Observation (NBO) System to characterize the behavioral pattern of newborns at biological and social risk. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2018;94:300–7.

Study carried out at Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG), Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil.