To assess the prevalence and pattern of behavioral problems in children and adolescents with atopic dermatitis (AD) and to study their associations with clinical data and severity.

MethodsThis was a single-center, cross-sectional study of patients (6–17 years) with AD. Assessment of competencies and syndrome scale scores of behavioral problems was performed by applying the Child Behavior Checklist 6–18 (CBCL 6–18) and AD severity using the Eczema Area Severity Index (EASI) score.

ResultsOf the 100 patients with AD, 56% were male, with a mean age of 11±3 years, and 43% had moderate/severe AD. Borderline or abnormal values were found in 75% of the patients for total social competence, 57% for internalization, 27% for externalization, and 18% for aggressive behavior. A higher prevalence of aggressive behavior (27.9% vs. 10.5%; p = 0.02) and sleep disorders (32.6% vs. 15.8%; p = 0.04) was observed in patients with moderate/severe AD than in those with mild AD. Children with current or previous use of immunosuppressants/immunobiological tests had a lower frequency of normal social competence (53% vs. 83%, p = 0.012). Regarding the critical questions, 8% responded affirmatively to suicidal ideation.

ConclusionA high prevalence of behavioral problems was observed among children and adolescents with AD, with a predominance of internalizing profiles, mainly anxiety and depression. Children with moderate/severe AD have a higher prevalence of aggressive behaviors and sleep disorders. These findings highlight the importance of multidisciplinary teams, including mental health professionals, in caring for patients with AD.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory skin disease characterized by pruritus and recurrent eczematous lesions, with an estimated prevalence of 6.8% in schoolchildren and 4.7% in adolescents in Brazil.1-3 Chronic AD is clinically characterized by eczema, which causes esthetic discomfort and social stigma due to the suspicion of a possible transmissible disease. A high prevalence of sleep disturbances, depression, anxiety, and decreased quality of life has been observed in affected adults,4-8 and studies in children and adolescents have reported similar results.9,10 There is evidence that the optimized treatment of AD significantly affects and improves a patient's quality of life.11-13

Assessing the emotional and behavioral aspects in scientific studies is challenging because of the subjectivity of symptoms. In this context, using validated instruments allows quantification and comparisons based on established cutoff points, making the evaluation more precise and standardized. The Child Behavior Checklist 6–18 (CBCL 6/18) is one of the most widely used instruments for screening psychological disorders.14,15 It is part of the Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment (ASEBA), validated by many scientific societies and cultural groups, and used in more than 10,000 scientific publications.16

Despite the growing number of studies on quality of life, sleep, and psychiatric comorbidities in adults with AD, only a few studies have evaluated these disorders in children and adolescents and their correlation with disease severity. Therefore, the study aimed to assess the prevalence and pattern of behavioral disorders in children and adolescents with AD and to determine associations with clinical data and disease severity.

MethodsThis study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Institution (no. 4.018.126). All participants signed an Agreement Form, and their guardians signed a Consent Form.

Children and adolescents (6–17 years old) diagnosed with AD17,18 and followed up for at least six months at a specialized clinic were included in the study. Patients were excluded if they had previously been diagnosed with visual, hearing, mental, or physical impairment; had other chronic diseases (neuropathies, cardiac, and metabolic diseases); had a guardian who had lived with the child for fewer than six months; could not understand the instructions regarding the study; or refused to participate or sign the Consent Form.

Behavioral disorders were evaluated using the CBCL 6/18, a questionnaire answered by parents consisting of 138 questions distributed as follows: the first 20 questions refer to social competence, subdivided into participation in activities, social relationships, and school, and the remaining 118 questions refer to behavioral problems. CBCL 6/18 evaluates the presence and profile of behavioral disorders, which can be an internalizing profile with a tendency toward depression, anxiety, and somatic disorders or an externalizing profile with aggressive and rule-breaking behaviors. Scales based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) were also analyzed. In addition, social, school, and attentional activities were evaluated and, like the other scales, were classified into clinical, borderline, or nonclinical ranges. The data from the questionnaires were entered into a specific software that generated T-scores, and classified according to the Brazilian validation. The classification of T-scores varies according to the analyzed scale, with the normal range being > 37 for total social competence, > 31 for the scales analyzed separately (social, activity, and school), lower than or equal to 69 for emotional and behavioral problems, and ≤ 63 for internalizing and externalizing problems.15

The evaluations were performed on a single day for each patient between June 2020 and February 2022. The patients’ guardians completed three questionnaires: CBCL 6/18, a questionnaire on clinical data (disease duration, treatments performed, and comorbidities), and another on socioeconomic aspects (family education and income). Patients underwent a summary physical examination to quantify AD severity using the Eczema Area Severity Index (EASI); AD was classified as mild (score 0.1–7), moderate (7.1–21), or severe (> 21).19-21 The researcher administered the questionnaires in cases where the guardian had incomplete primary education or difficulty understanding the questionnaires.14

For the descriptive analysis, the quantitative variables are presented as means and standard deviations for normal distributions and as medians and interquartile intervals for non-normal distributions with relevant outliers. Normality was determined using graphical analysis and the Shapiro-Wilk test. Categorical variables are presented as frequencies and percentages.

The association between AD severity, total social competence, and behavioral disturbances was evaluated using a nonparametric test (Mann-Whitney U test). Results were considered significant at p < 0.05. Analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 28 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

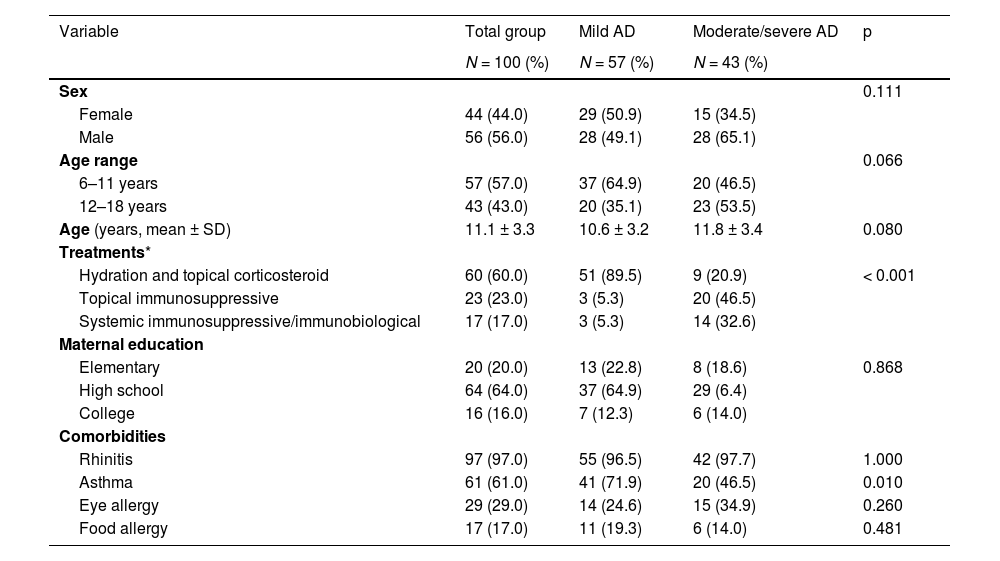

ResultsFourteen children with AD were excluded (four due to severe uncontrolled asthma, three due to cognitive impairment, three because they did not live with the caregiver, and four who declined to participate). One hundred patients were included in the study, all between the ages of six and 17 years (mean age 11 ± 3 years); 56% were male. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with atopic dermatitis (AD; N = 100).

| Variable | Total group | Mild AD | Moderate/severe AD | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 100 (%) | N = 57 (%) | N = 43 (%) | ||

| Sex | 0.111 | |||

| Female | 44 (44.0) | 29 (50.9) | 15 (34.5) | |

| Male | 56 (56.0) | 28 (49.1) | 28 (65.1) | |

| Age range | 0.066 | |||

| 6–11 years | 57 (57.0) | 37 (64.9) | 20 (46.5) | |

| 12–18 years | 43 (43.0) | 20 (35.1) | 23 (53.5) | |

| Age (years, mean ± SD) | 11.1 ± 3.3 | 10.6 ± 3.2 | 11.8 ± 3.4 | 0.080 |

| Treatments* | ||||

| Hydration and topical corticosteroid | 60 (60.0) | 51 (89.5) | 9 (20.9) | < 0.001 |

| Topical immunosuppressive | 23 (23.0) | 3 (5.3) | 20 (46.5) | |

| Systemic immunosuppressive/immunobiological | 17 (17.0) | 3 (5.3) | 14 (32.6) | |

| Maternal education | ||||

| Elementary | 20 (20.0) | 13 (22.8) | 8 (18.6) | 0.868 |

| High school | 64 (64.0) | 37 (64.9) | 29 (6.4) | |

| College | 16 (16.0) | 7 (12.3) | 6 (14.0) | |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Rhinitis | 97 (97.0) | 55 (96.5) | 42 (97.7) | 1.000 |

| Asthma | 61 (61.0) | 41 (71.9) | 20 (46.5) | 0.010 |

| Eye allergy | 29 (29.0) | 14 (24.6) | 15 (34.9) | 0.260 |

| Food allergy | 17 (17.0) | 11 (19.3) | 6 (14.0) | 0.481 |

SD, standard deviation.

Allergic rhinitis and asthma were present in 97% and 61% of the patients, respectively. The EASI ranged from 1 to 34.1, with 43% of the patients classified as having moderate/severe AD. Seventeen patients (17%) were currently using immunosuppressive or immunobiological medications, and 15% had previously used these medications. The total CBCL 6/18 social competence T-scores ranged from 22 to 57, with 25% of the patients with AD having a normal score (score > 40), 10% borderline (score 37–40), and 65% within the clinical range (score < 37). When social, school, and activity functioning were assessed separately, the activity scale was the most compromised (altered in 32% and borderline in 36% of the cases).

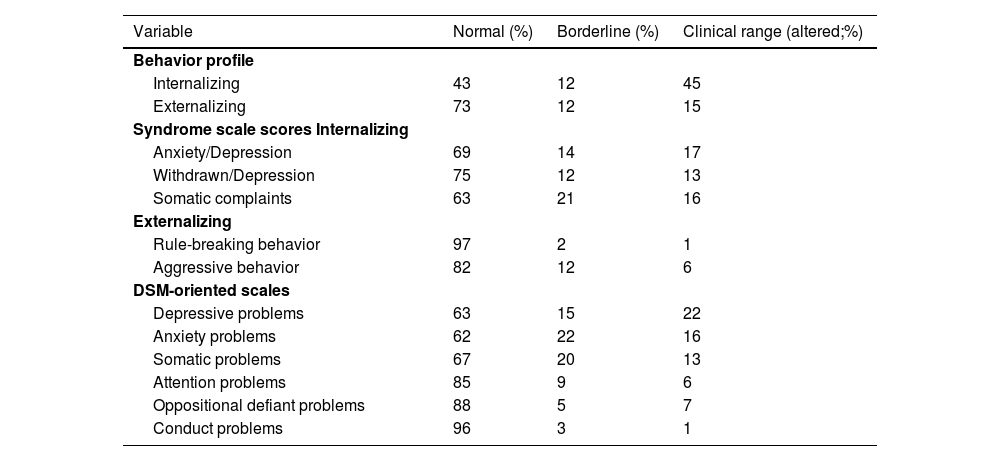

An internalizing profile was found in 45% and borderline in 12% of the patients, whereas an externalizing profile was found in 15% of the children in the clinical range and 12% in the borderline range, as presented in Table 2. Anxiety and depression were the most common symptoms among patients with an internalizing profile.

Behavioral problems assessed by the CBCL 6/18 in children and adolescents with atopic dermatitis (N = 100).

DSM, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

The demographic characteristics (age, sex, and maternal education) of the patients were similar when stratified according to AD severity. As expected, significant differences were observed in the treatments used between the mild and moderate/severe AD groups. The authors observed a higher prevalence of asthma in the mild AD group than in the moderate/severe AD group (Table 1).

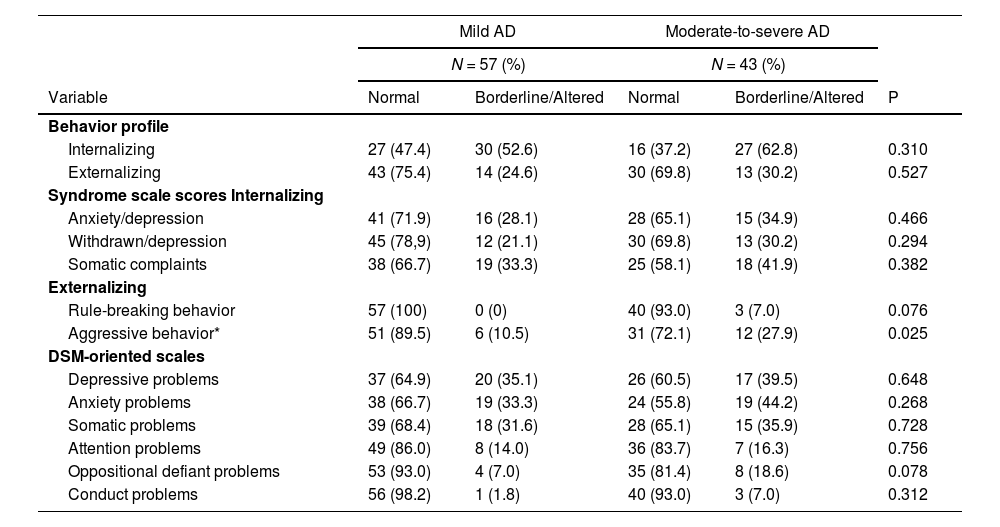

Table 3 shows the profiles of the patient's behavioral disturbances according to the severity of AD. There were no differences in the total score, activities, social and school functioning, or the DSM-guided scale. The prevalence of aggressive behaviors was higher in the moderate/severe AD group than in the mild AD group (27.9% vs. 10.5%; p = 0.025).

Behavior problems assessed by the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL 6/18) in patients with mild and moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (AD).

DSM, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

Children with current or past use of immunosuppressive/immunobiological medications were less likely to have normal social competence than those who did not use these drugs (53% vs. 83%; p = 0.012).

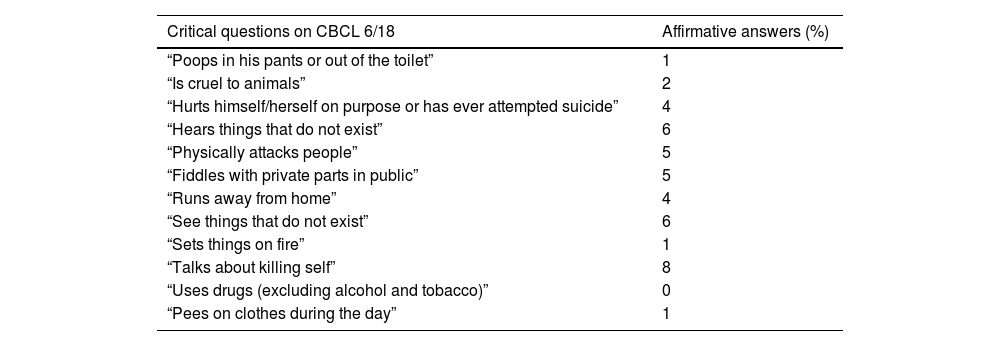

The frequencies of the responses to the CBCL 6/18 critical items are listed in Table 4. The question “talks about killing self” had the highest frequency of affirmative answers (8%). There were no significant differences in the responses according to AD severity.

Answer to the critical questions on the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL 6/18) in patients with atopic dermatitis (N = 100).

Sleep disturbance was reported by the guardians of nine (15.8%) patients in the mild AD group and 14 (32.6%) in the moderate/severe AD group (p = 0.04).

DiscussionIn the present study, the total social competence score was borderline or clinical in 75% of patients, with an internalizing profile in 57% of those assessed. The authors found borderline or clinical scores for depressive and anxiety problems in 37% and 38% of the patients, respectively. On comparing the mild and moderate/severe AD groups, the authors observed a higher prevalence of aggressive behaviors and sleep disturbances in patients with moderate/severe AD.

Children and adolescents with AD often showed impairments in social competence, which were most pronounced in participation in activities such as playing. This finding is consistent with that of other studies.22 Fontes Neto et al., in a Brazilian case-control study, also showed impairment of social competence in children with AD, with a difference in the domain of daily activities (median of 2.5 in the AD group vs. 5.0 in the control group, p = 0.002), a higher prevalence of internalizing profile (median 22.0 vs. 12.0, p = 0.001), somatic problems scale (median 5.0 vs. 2.0, p = 0.001), anxiety/depression (9.0 vs. 5.0, p = 0.002), and aggressive behavior (18.0 vs. 11.0, p = 0.001), findings which are similar to ours. 22 In the present study, the authors did not compare patients with AD to a control group, and we chose to compare our results with the Brazilian reference values (normal, borderline, and clinical). This option results in a loss of statistical power due to data aggregation but has greater clinical relevance and applicability to health care.

The authors observed that nearly half of the patients with AD exhibited CBCL values for internalizing problems in the clinical range, consistent with previous studies. Depression and anxiety are highly prevalent psychiatric disorders in children and adults with AD.4,10,22-24 According to Muzzolon et al., the risk of mental disorders in the pediatric population with AD in a hospital in Curitiba was 63%, with a higher prevalence of internalizing disorders (42%), similar to the present study. In addition, they observed a high prevalence of sleep disturbances (60%), social problems (32%), and anxiety/depression (25%).25 This high prevalence, especially of depression and anxiety, is consistent with the present findings and those of other studies.4,10,22-24

A recent meta-analysis of five pediatric studies (including 46,857 patients with AD and 402,292 without AD) showed an association between AD and depressive symptoms.26 The results were also significant in adults, with a 2.19 increased risk of depressive symptoms and a 2.19 increased risk for anxiety symptoms.26 The higher prevalence of depressive symptoms in AD patients was also found in a large Korean study with 72,435 children and adolescents, with 37.0% in patients vs. 30.5% in controls (OR:1.24 [1.15 - 1.34]).9

Regarding aggressive behavior, the authors observed a higher prevalence of abnormal values in patients with moderate/severe AD (27.9% vs. 10.5%, p = 0.025), which was different from that reported by Muzzolon et al. (mild AD: 22.4% vs. severe AD: 16.7%, p = 0.64). Although a statistical divergence between the results was not confirmed, the observed values were comparable. These discrepancies may be due to the different population characteristics in the different states.25

In the present study, the authors obtained 8% of positive responses to the “talks about killing self” questionnaire, with no differences in AD severity. A meta-analysis of six studies involving adults and children with AD found an association between AD and suicidal ideation.23 One of these studies focused on adolescents and found consistent results for different items associated with suicide: suicidal ideation, 21.3%; suicide planning, 8.0%; and suicide attempts, 6.1%.23 It should be emphasized that the questionnaire used in the present study was a screening questionnaire, and the patients were referred for psychiatric evaluation for more definitive conclusions regarding their behavioral problems and appropriate follow-up.

With due methodological caveats, the observed prevalence of behavioral problems was similar to that found in a Brazilian study of public school students.27 The present study showed no significant differences in the internalizing and externalizing profiles or the DSM-guided scales between children with mild AD and those with moderate/severe AD.

A Brazilian cross-sectional study found no difference in the prevalence of internalizing disorders between mild (39.7%) and moderate/severe (45%) AD groups.25 However, these findings remain controversial. A ten-year follow-up cohort study of 11,181 children showed an increase in the percentage of lifetime depression (6% at age ten, 21.6% at age 18) and also a higher prevalence of depressive symptoms (aOR: 2.38 [95%CI: 1.21 - 4.72]) and internalizing profile (aOR: 1.90 [95%CI: 1.14 - 3.16]) in patients with severe AD.24

Some factors may have influenced the assessment of behavioral problems according to AD severity, such as the more significant presence of asthma in those with mild AD, a condition known to affect the quality of life, and the sample size, which limits subgroup analyses.

Current or past treatment with immunobiological/immunosuppressive agents is associated with a more significant impairment of social functioning. This is relevant because the EASI represents the present stage of the disease and does not consider past severity or the current therapy needed for better control. Altered social competence is a primary component of healthy mental development. Its impairment may be associated with internalizing and externalizing disorders in childhood and adolescence, possibly extending into adulthood.28

The authors identified sleep disturbances, particularly in the subgroup with moderate/severe AD. In a previous cohort study, children with active AD were more likely to report worse sleep quality. Children with more severe active disease had worse sleep quality. However, even children with mild AD had statistically significantly increased odds of impaired sleep quality.5 A study of adults with AD showed a higher prevalence of fatigue, insomnia, and daytime sleepiness in patients with AD.6

The present study has some limitations. The sample size was relatively small and limited by the number of eligible children in the clinic. Information was obtained from only one guardian; therefore, the possibility of a disagreement between parents cannot be ruled out. In addition, the lack of a control group partially limits the interpretation of the findings of the high prevalence of behavioral problems in children with AD. Because the authors used a validated questionnaire in Portuguese with established reference values for the Brazilian population, it was possible to extrapolate some comparisons with the general Brazilian pediatric population.

Notably, this study was conducted during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, which caused social isolation, financial insecurity, and the possible death of people close to the children. It is very difficult to estimate the potential impact of the pandemic on these children because reduced social interaction may not only be a stressor but also a protective factor for adolescents with more severe skin conditions and victims of prejudice and isolation at school.

In conclusion, the authors observed a high frequency of behavioral problems in children and adolescents with AD, with a predominance of internalizing profiles, particularly anxiety and depression. Children with moderate/severe AD had a higher prevalence of aggressive behaviors and sleep disturbances, whereas those with current or past use of immunosuppressive/immunobiological medications had more significant social impairment. These findings highlight the importance of multidisciplinary teams, including mental health professionals, in caring for patients with AD.

Contribution of each author- •

Marília Magalhães Moraes: study design, data collection and review, analysis of results, article preparation, final review and approval.

- •

Fernanda Pires Cecchetti Vaz: data collection, article preparation, final review and approval.

- •

Raíssa Monteiro Soares dos Anjos Roque: data collection, article preparation, final review and approval.

- •

Márcia de Carvalho Mallozi: study design, article preparation, final review and approval.

- •

Dirceu Solé: study design, article preparation, final review and approval.

- •

Gustavo Falbo Wandalsen: study design, data review, analysis of results, article preparation, final review and approval.

Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - Brasil (CAPES).