To evaluate neopterin plasma concentrations in patients with active juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) and correlate them with disease activity.

MethodsSixty patients diagnosed as active JIA, as well as another 60 apparently healthy age- and gender-matched children as controls, were recruited from the Pediatrics Allergy and Immunology Clinic, Ain Shams University. Disease activity was assessed by the Juvenile Arthritis Disease Activity Score 27 (JADAS-27). Laboratory investigations were performed for all patients, including determination of hemoglobin concentration (Hgb), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and C-reactive protein. Serum concentrations of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), and neopterin were measured.

ResultsSignificant differences were found between JIA patients and controls with regard to the mean levels of Hgb, ESR, TNF-α, IL-6, and MCP-1 (p<0.05). A statistically significant higher mean level serum neopterin concentration (p<0.05) was found in JIA patients (20.43±8.73 nmol/L) than in controls (6.88±2.87 nmol/L) (p<0.05). Positive significant correlations were detected between serum neopterin and ESR, TNF-α, IL-6, MCP-1, and JADAS-27 (p<0.05). No correlation was found between serum neopterin and CRP (p>0.05). Multiple linear regression analysis showed that JADAS- 27 and ESR were the main variables associated with serum neopterin in JIA patients (p<0.05).

ConclusionThe elevation of plasma neopterin concentrations in early JIA patients may indicate stimulation of immune response. Serum neopterin can be used as a sensitive marker for assaying background inflammation and disease activity score in JIA patients.

avaliar as concentrações plasmáticas de neopterina em pacientes com artrite idiopática juvenil (AIJ) ativa e correlacioná-las com a atividade da doença.

MétodosSessenta pacientes diagnosticados com AIJ ativa, bem como outras 60 crianças aparentemente saudáveis com a mesma idade e sexo no grupo de controle, foram recrutados da clínica de Alergia e Imunologia Infantil da Universidade Ain Shams. A atividade da doença foi avaliada pelo Escore de Atividade da Doença da Artrite Juvenil em 27 Articulações (JADAS-27). Foram realizadas investigações laboratoriais em todos os pacientes, incluindo a determinação da concentração de hemoglobinas, a taxa de sedimentação de eritrócitos e a proteína C-reativa. Foram mensuradas as concentrações séricas do fator de necrose tumoral alfa, interleucina-6 e proteína quimiotática de monócitos-1 e neopterina.

ResultadosFoi encontrada uma diferença significativa entre os pacientes com AIJ e os controles quanto às médias de Hb, TSE, FNT-α, IL-6 e MCP-1 (p<0,05). Foi encontrado um nível estatística e significativamente maior de concentração média de neopterina sérica (p<0,05) em pacientes com AIJ (valor médio de 20,43±8,73 nmol/L) que em controles (valor médio de 6,88±2,87 nmol/L) (p<0,05). Foram detectadas correlações positivas significativas entre a neopterina sérica e a TSE, FNT-α, IL-6, MCP-1 e JADAS-27 (p<0,05). Não foi encontrada nenhuma correlação entre a neopterina sérica e a PCR (p>0,05). A análise de regressão linear múltipla mostrou que o JADAS-27 e a TSE foram as principais variáveis associadas à neopterina sérica em pacientes com AIJ (p<0,05).

ConclusãoA elevação das concentrações plasmáticas de neopterina em pacientes com AIJ precoce pode indicar um estímulo de resposta imune. A neopterina sérica pode ser usada como um indicador sensível para analisar o histórico de inflamações e o escore de atividade da doença em pacientes com AIJ.

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is generally considered a clinical syndrome involving several disease subsets, with a number of inflammatory flows, leading to an eventual common pathway in which persistent synovial inflammation and associated damage to articular cartilage and underlying bone are present.1 One main inflammatory process in the pathophysiology of the JIA consists of overproduction of tumor necrosis factor that leads to overproduction of many cytokines such as interleukin-6, which causes persistent inflammation and joint destruction.2–4 The disease arises in a genetically susceptible individual due to environmental factors.5 Moreover, it has been proposed that an antigen-driven autoimmune process mediates the inflammatory pathology in some cases of arthritis (e.g., oligoarthritis, polyarthritis). In contrast, there are no signs of lymphocyte-mediated, antigen-specific immune responses in individuals with systemic onset disease. Recent investigations in the pathophysiology of systemic onset disease have indicated that this disorder is due to an uncontrolled activation of the innate immune system.6 Regardless of the differences in the underlying pathogenesis of the various types of JIA, pro-inflammatory cytokines are consistently overproduced and are related to the clinical manifestations in all types of JIA.7

The International League of Associations for Rheumatology (ILAR) classification system divides JIA into seven clinical subgroups.8 The few population based estimates available indicate that the prevalence of JIA is approximately one to two per 1,000 children, and the incidence is 11 to 14 new cases per 100,000 children.9

Neopterin, a pyrazino-pyrimidine compound, is synthesized by monocytes and macrophages in response to interferon-γ (IFN-γ) produced by activated T-cells. It is a marker of cellular immune response, and levels are elevated in conditions of T-cell or macrophages activation, including autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis.10,11

The current study was undertaken to assess the association of plasma level of neopterin with inflammatory and disease activity in JIA patients.

Subjects and methodsThe present study included 60 patients (30 males and 30 females) diagnosed as active JIA (Group 1) as well as 60 apparently healthy age- and gender-matched children as controls (Group 2). Patients were recruited from the Pediatrics Allergy and Immunology Clinic, Ain Shams University. Written informed consent was obtained from parents after explanation of the aim of the study. The protocol and all corresponding documents were approved by Ethical and Research Committee of the National Research Center. Age ranged from 5 to 15 years with a mean age 12.20±2.8 years. Patients were eligible if they met the Edmonton International League of Associations for Rheumatology criteria (second revision) for a diagnosis of JIA.8 Disease activity was measured using a validated score, the JADAS-27 (Juvenile Arthritis Disease Activity Score-27).12 This score includes four measures: physician global assessment of disease activity using a visual analog scale (VAS), parent global assessment of child's well-being determined by a VAS, count of joints with active disease (evaluating 27 joints), and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). ESR is normalized to a score ranging from 0 to 10, by the formula (ESR-20)/10. JADAS-27 is calculated as the simple linear sum of the scores of its four components, which yields a total score of 0-57, with higher scores associated with worse disease activity. Thirty-eight patients (63.3%) had polyarticular onset JIA, 15 patients (25%) had pauciarticular onset, and seven patients (11.7%) had systemic onset.

All patients had full history taken and were subjected to clinical examination. Laboratory investigations were performed for all patients, including determination of hemoglobin concentration (Hgb in g/dL), ESR in mm/h by Westergren method, and C-reactive protein (CRP in mg/L) detection by the latex agglutination slide test. Serum concentrations of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) were measured by multiplex enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Millipore®, Merck KgaA, Darmstadt, Germany).

Assay of serum neopterin (nmol/L)Serum neopterin levels were examined using an ELISA kit (Neopterin ELISA, IBL, Hamburg, Germany). The assay is based on the basic principle of competition between a peroxide-conjugated and non-conjugated antigen for a fixed number of antibody binding sites. The peroxidase conjugated, antigen-antibody complexes bind to the wells of the micro filter strips, which are coated with a good anti-rabbit antibody. Unbounded antigen is then removed by washing. After the substrate reaction, the optical density is measured at 450nm. A standard curve is plotted and neopterin concentration in the sample is determined by interpolation from the standard curve.

Statistical analysisStatistical analysis was performed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 16 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Continuous data were expressed as mean±standard deviation and were compared by Student's t-test. Pearson's correlation analysis was conducted to evaluate the association between continuous exposure and continuous covariates. Multiple linear regression analysis was performed to identify the influence of multiple variables (age, sex, ESR, CRP, TNF-α, IL-6, MCP-1, and JADAS-27) on a dependent variable (serum neopterin). p<0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

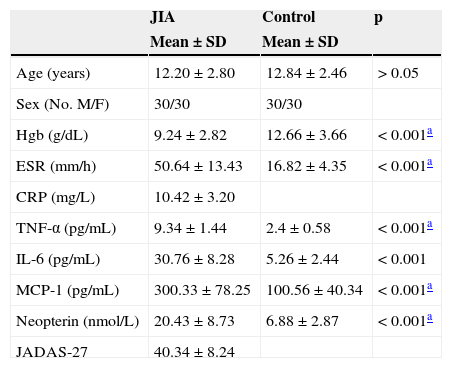

ResultsThe clinical characteristics of patients with JIA and control subjects are shown in Table 1. No significant difference was detected between patients and controls as regard to their mean ages (p>0.05). However, significant differences were found between both groups with regard to the means of the other variables (Hgb, ESR, TNF-α, IL-6, MCP-1, and neopterin; p<0.05).

Demographic, biochemical, and disease characteristics of all subjects.

| JIA | Control | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean±SD | Mean±SD | ||

| Age (years) | 12.20±2.80 | 12.84±2.46 | > 0.05 |

| Sex (No.M/F) | 30/30 | 30/30 | |

| Hgb (g/dL) | 9.24±2.82 | 12.66±3.66 | < 0.001a |

| ESR (mm/h) | 50.64±13.43 | 16.82±4.35 | < 0.001a |

| CRP (mg/L) | 10.42±3.20 | ||

| TNF-α (pg/mL) | 9.34±1.44 | 2.4±0.58 | < 0.001a |

| IL-6 (pg/mL) | 30.76±8.28 | 5.26±2.44 | < 0.001 |

| MCP-1 (pg/mL) | 300.33±78.25 | 100.56±40.34 | < 0.001a |

| Neopterin (nmol/L) | 20.43±8.73 | 6.88±2.87 | < 0.001a |

| JADAS-27 | 40.34±8.24 |

JIA, juvenile idiopathic arthritis; Hgb, hemoglobin concentration; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; CRP, C-reactive protein; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-alpha; IL-6, interleukin-6; MCP-1, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; JADAS-27, Juvenile Arthritis Disease Activity Score-27.

Demographic and biochemical characteristic were compared between males and females in the patients group in Table 2. Mean JADAS-27 was higher in females than in males and the difference was significant (p<0.05), while no significant differences were detected as regard to the other variables.

Demographic, biochemical, and disease characteristics in male and female JIA patients.

| Males | Females | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean±SD | Mean±SD | ||

| Age (years) | 12.15±3.25 | 11.96±2.76 | > 0.05 |

| Hgb (g/dL) | 9.54±3.36 | 9.16±2.49 | > 0.05 |

| ESR (mm/h) | 48.54±11.63 | 51.47±10.33 | > 0.05 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 9.72±2.47 | 12.47±3.43 | |

| TNF-α (pg/mL) | 8.24±1.46 | 10.04±1.37 | > 0.05 |

| IL-6 (pg/mL) | 29.46±6.46 | 31.46±4.67 | > 0.05 |

| MCP-1 (pg/mL) | 295.33±78.25 | 304.74±38.23 | > 0.05 |

| Neopterin (nmol/L) | 19.84±7.49 | 20.16±2.42 | > 0.05 |

| JADAS-27 | 38.56±8.46 | 49.38±10.36 | < 0.05a |

JIA, juvenile idiopathic arthritis; Hgb, hemoglobin concentration; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; CRP, C-reactive protein; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-alpha; IL-6, interleukin-6; MCP-1, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; JADAS-27, Juvenile Arthritis Disease Activity Score-27.

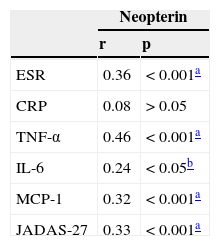

The correlations between serum neopterin, disease activity, and inflammatory mediators in patients with JIA are shown in Table 3. Positive significant correlations were detected between serum neopterin and ESR, TNF-α, IL-6, MCP-1, and JADAS-27 (p<0.05). No significant correlation was found between serum neopterin and CRP (p>0.05).

Correlations between neopterin, inflammatory markers, and disease activity in JIA patients.

| Neopterin | ||

|---|---|---|

| r | p | |

| ESR | 0.36 | < 0.001a |

| CRP | 0.08 | > 0.05 |

| TNF-α | 0.46 | < 0.001a |

| IL-6 | 0.24 | < 0.05b |

| MCP-1 | 0.32 | < 0.001a |

| JADAS-27 | 0.33 | < 0.001a |

JIA, juvenile idiopathic arthritis; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; CRP, C-reactive protein; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-alpha; IL-6, interleukin-6; MCP-1, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; JADAS-27, Juvenile Arthritis Disease Activity Score-27.

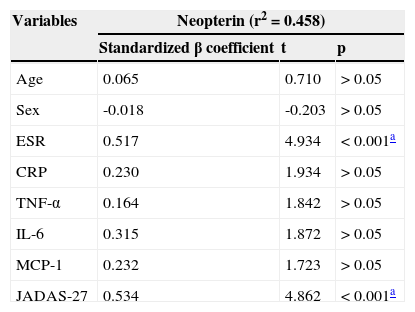

Multiple linear regression analysis for the association of the different variables with serum neopterin is shown in Table 4. After adjustment for age, sex, and inflammatory markers, JADAS-27 and ESR were the main predictors for the high neopterin levels seen in patients with JIA (p<0.05). The effects of TNF- α, IL-6, and MCP-1 were attenuated by the adjustment of all the variables.

Multiple linear regression analysis for neopterin and different independent variables.

| Variables | Neopterin (r2=0.458) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Standardized β coefficient | t | p | |

| Age | 0.065 | 0.710 | > 0.05 |

| Sex | -0.018 | -0.203 | > 0.05 |

| ESR | 0.517 | 4.934 | < 0.001a |

| CRP | 0.230 | 1.934 | > 0.05 |

| TNF-α | 0.164 | 1.842 | > 0.05 |

| IL-6 | 0.315 | 1.872 | > 0.05 |

| MCP-1 | 0.232 | 1.723 | > 0.05 |

| JADAS-27 | 0.534 | 4.862 | < 0.001a |

JIA, juvenile idiopathic arthritis; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; CRP, C-reactive protein; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-alpha; IL-6, interleukin-6; MCP-1, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; JADAS-27, Juvenile Arthritis Disease Activity Score-27.

The present study showed a high level of serum neopterin, as a marker of macrophage activation, in patients with JIA. Neopterin and ESR are significant predictors for disease activity in such patients.

Previous studies of neopterin in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) have been performed to define the relationship between neopterin and disease activity. Generally, they found that neopterin correlated with disease activity in RA and decreased with treatment.11,13,14 In contrast to the current study, a previous study in Japan detected significantly increased neopterin in SLE (Systemic Lupus Erythematosus) patients (p<0.001) but not in RA patients. However, patients with RA had a greater concentration of neopterin in synovial fluid.15

Regarding recent studies, Rho et al., in 2011,16 showed that neopterin concentrations were significantly higher in patients with SLE (median 8.0, [6.5–9.8] nmol/L) and RA (6.7, [5.3–8.9] nmol/L) than controls (5.7, [4.8–7.1] nmol/L), and were higher in SLE than RA (all p<0.001). In SLE, neopterin was significantly correlated with higher ESR (p=0.001), TNF-α (p<0.001), MCP-1 (p=0.005), and homocysteine concentrations (p=0.01), but in RA only with ESR (p=0.01). The results of this study were in agreement with that in the current study. In 2012, Ozkan et al.17 evaluated the usefulness of tryptophan degradation and neopterin levels in active rheumatoid arthritis patients under therapy. They found that neopterin levels correlated positively with kynurenine (r=0.582, p<0.02), kynurenine/tryptophan (r=0.486, p<0.05), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (r=0.472, p<0.05), and RF (r=0.478, p<0.05) in a group of rheumatoid arthritis patients, which are in concordance with the results of the present study. However, contrary to the present results, they found that neopterin and TNF-α levels did not show statistically significant differences between patient and control groups. The difference may be due to the age range in their study, as it was adult group. In 2013, D’agostino et al.18 evaluated neopterin plasma concentrations in patients with early Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) and correlated them with disease activity. In agreement with the present results, they detected a statistically significant elevation of neopterin mean concentration in early RA patients: mean value of 8.92±0.93 [3.94-28.3] nmol/L (p<0.001). Pearson product moment correlation suggested a correlation between neopterin concentrations and DAS-28 (r=0.208, p=0.065). Similar results were obtained by Arshadi et al.,19 who detected significantly higher level of neopterin in RA patients compared to healthy controls. Moreover, plasma neopterin level was increased in patients with active disease and also was correlated with disease activity parameters. The previous results are in concordance with the present study. But in contrast with the present study, they found a higher neopterin level in male RA patients versus female patients and a significant correlation of plasma level of neopterin with age in both the RA and control group. The difference in the results may be attributed to the adult age group of their study compared to the young age group in the present study. Also Fagerer et al., in 2013,20 studied the involvement of specific chemokines in the inflammatory process of patients with RA and cardiovascular disease with activated production of the pteridine neopterin. In agreement with the current study, they found high neopterin levels in RA patients and significantly elevated concentrations of neopterin in patients with RA plus cardiovascular disease (CVD) compared to RA without CVD (p<0.03).

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, few studies have included both neopterin as a pro-inflammatory marker and JIA. Two studies found high serum concentrations of IL-10, IL-18, IL-6, and neopterin in patients with systemic JIA complicated by macrophage activation syndrome. They found that IL-10 and IL-18 remained elevated in the inactive disease, while other pro-inflammatory cytokines normalized in the inactive phase of the disease.21,22 In 2014, Brunner et al. 23 evaluated tryptophan as biomarker in JIA and correlated it with neopterin in serum and synovial fluid. They detected that serum tryptophan showed no relevant difference in JIA patients vs. controls in contrast to neopterin, which was higher in patients than controls.

The present study has several limitations. It was cross-sectional in design, and therefore causal inferences cannot be drawn. Also, the effects of the type of therapy on neopterin levels were not followed, so their use as a marker for therapy efficacy cannot be evaluated. The relatively small sample size could be responsible for inadequate statistical power. Larger sample sizes would have increased numbers within each JIA category, allowing for greater precision in assessing the pro-inflammatory markers between categories.

In conclusion, the present study emphasized that macrophage activation, reflected by increased serum neopterin, is a sensitive marker for assaying background inflammation and disease activity score in JIA patients.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Abu Shady MM, Fathy HA, Ali A, Youness ER, Fathy GA. Association of neopterin as a marker of immune system activation and juvenile rheumatoid arthritis activity. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2015;91:352–7.