To describe the association between electronic devices in the bedroom with sedentary time and physical activity, both assessed by accelerometry, in addition to body mass index in children from São Caetano do Sul.

MethodsThe sample consisted of 441 children. The presence of electronic equipment (television, personal computer, and videogames) in the bedroom was assessed by a questionnaire. For seven consecutive days, children used an accelerometer to objectively monitor the sedentary time and moderate-to-vigorous physical activity. Body mass index was categorized as suggested by the World Health Organization.

ResultsOverall, 73.9%, 54.2% and 42.8% of children had TV, computer, and videogames in the bedroom, respectively, and spent an average of 500.7 and 59.1min/day of sedentary time and moderate-to-vigorous physical activity. Of the children, 45.3% were overweight/obese. Girls with a computer in the bedroom (45min/day) performed less moderate-to-vigorous physical activity than those without it (51.4min/day). Similar results were observed for body mass index in boys. Moderate-to-vigorous physical activity was higher and body mass index was lower in children that had no electronic equipment in the bedroom. Presence of a computer (β=−4.798) and the combination TV+computer (β=−3.233) were negatively associated with moderate-to-vigorous physical activity. Videogames and the combinations with two or three electronic devices were positively associated with body mass index. Sedentary time was not associated with electronic equipment.

ConclusionElectronic equipment in the children's bedroom can negatively affect moderate-to-vigorous physical activity and body mass index regardless of gender, school, and annual family income, which can contribute to physical inactivity and childhood obesity.

Descrever a associação entre equipamentos eletrônicos no quarto com tempo sedentário e atividade física, ambos avaliados por acelerometria, além do índice de massa corporal (IMC) em crianças de São Caetano do Sul.

MétodosA amostra foi composta por 441 crianças. A presença de equipamentos eletrônicos (televisão ou TV, computador e jogos de vídeo) no quarto foi avaliada por meio de um questionário. Durante sete dias consecutivos, as crianças usaram acelerômetro para monitorar objetivamente o tempo sedentário e atividade física de moderada a vigorosa (AFMV). O IMC foi categorizado conforme sugerido pela Organização Mundial de Saúde.

ResultadosNo total, 73,9%, 54,2% e 42,8% das crianças tinham TV, computador e jogos de vídeo no quarto, e gastavam em média 500,7 e 59,1min/dia de tempo sedentário e de AFMV. Das crianças, 45,3% tinham excesso de peso/obesidade. Meninas com computador no quarto (45min/dia) faziam menos AFMV do que as que não tinham (51,4min/dia). Resultados semelhantes ocorreram para o IMC nos meninos. AFMV foi maior e IMC menor nas crianças que não tinham equipamentos eletrônicos no quarto. Computador (β= -4,798) e a combinação de TV com computador (β= -3,233) foram negativamente associados com AFMV. Jogos de vídeo e as combinações com dois ou três equipamentos eletrônicos foram positivamente associados com IMC. Tempo sedentário não foi associado com equipamentos eletrônicos.

ConclusãoEquipamentos eletrônicos no quarto das crianças podem afetar negativamente a AFMV e o IMC independentemente do sexo, escola e renda familiar anual, podendo contribuir para a inatividade física e obesidade infantil.

Sedentary behavior, such as the use of electronic equipment (TV, personal computer, and videogames) in the children's bedroom, is highly prevalent during childhood1 and may be associated with health risks.2 In Brazil and other countries, public health guidelines recommend that children should minimize the amount of time spent in prolonged sedentary behavior.3,4 The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that parents should remove electronic equipment from children's rooms.5

Because 78.6% of Brazilian children watch >2h/day of TV,6 the influence of electronic equipment in the children's lifestyle has been a key area of research7,8; for instance, the impact of the presence of electronic equipment in their rooms.9 Studies carried out in developed countries have found high levels of adiposity10,11 and low levels of physical activity12 in children that maintain electronic equipment in the bedroom. Moreover, in a representative sample of English children participating in the study Sport, Physical Activity, and Eating Behaviour: Environmental Determinants in Young People (SPEEDY), Atkin et al.9 reported higher means of sedentary time (objectively assessed) in children that had a TV and computer in the bedroom, when compared to those who did not.

The objective assessment of physical activity measured by an accelerometer provides detailed data representing physical activity intensities, such as moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA), and even the sedentary time. Studies using accelerometers have become more common in research on childhood physical activity worldwide.8 However, the number of studies in developing countries, such as Brazil, which used accelerometers is still very small. Thus, the aim of this study is to describe the association between the presence of electronic devices in the bedroom with sedentary time and physical activity, both assessed by accelerometry, in addition to body mass index (BMI) in children from São Caetano do Sul, Brazil.

Material and methodsSample studyThis study is part of the International Study of Childhood Obesity, Lifestyle, and the Environment (ISCOLE), which is characterized as a cross-sectional multicenter study conducted in twelve countries.8 The details of ISCOLE have been previously published.8

The present study focuses on data collected in the city of São Caetano do Sul, in the state of Sao Paulo, Brazil, which has an area of 15.3km2 and a subtropical climate. The city's population in 2013 consisted of 149,263 inhabitants, including 1557 children (812 boys and 745 girls) aged 10 years.13 The main economic activity of the city consists of the service sector,13 and the municipality has the best Human Development Index of Brazil (0.86).14

Initially, contact was made with the Department of Education and then the invitation to participate in the project was made. After the approval, the project was presented at each school as well as the council of parents; after obtaining the authorization, the project was implemented in each school. All children attending the 5th grade of Elementary School were invited to participate.

There is some variability in the socioeconomic status between schools in São Caetano do Sul. Public schools represent the lowest and lower-middle socioeconomic classes, while private schools represent the middle and upper-middle classes. Random lists of elementary schools were generated, considering the number of schools (16 public and 4 private), and they were selected from each list in a four (public) to one (private) ratio. When a school refused to participate, it was replaced by the following school on the list. Twenty schools were selected, in order to obtain a sample of 25–30 children from each school.

Data collection was performed in the period between March 2012 and April 2013 and all measurements were conducted throughout an entire week per school. All data collection and management activities were carried out and monitored according to the quality control procedures implemented by the coordinating center of ISCOLE.8

Overall, 564 children (277 boys and 287 girls) were assessed and met the following inclusion criteria: (a) age between 9 and 11 years old; (B) regularly attending a school in São Caetano do Sul; and (c) no clinical or functional limitations that would prevent the practice of daily physical activity. After the exclusion criteria (invalid data from electronic equipment and accelerometry), the final sample consisted of 441 children (216 boys and 225 girls). Before participating in the study, the children's parents and/or guardians signed an informed consent, according to Resolution 196/96 of Conselho Nacional de Saúde do Brasil (National Health Council of Brazil). The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Universidade Federal de São Paulo, Brazil.

Electronic equipmentThe presence and type (TV, computer, and videogames) of electronic equipment in the children's bedrooms were reported through the Neighborhood and Home Environment Questionnaire.8 To adapt the questionnaire, three health professionals were invited to participate in the respective phases. Detailed information on the questionnaire were sent and separate meetings were carried out with each professional until a consensus was reached regarding the questionnaire composition, the questions, the forms of the requested responses, and the result analysis procedures. Parents and/or guardians answered the questions regarding the presence of TV, computer, and videogames in the children's bedrooms, and the response to each item was “yes” or “no.”

AccelerometryThe Actigraph GT3X accelerometer (ActiGraph®, USA) was used to objectively monitor the sedentary time and MVPA. The accelerometer was worn at the waist attached to an elastic belt, in the mid-axillary line on the right side. Participants were encouraged to use the accelerometer 24h/day for at least seven days (plus another day of initial familiarization and during the morning of the last day), including the two weekend days. The minimum amount of accelerometer data considered acceptable for analysis was four days (including at least one weekend day), with at least 10-h/day of use, after removal during sleeping time.15,16

After the last day of data collection, the research team went to school to remove accelerometers. The research team verified whether the data were complete using the latest version of Actilife software (ActiGraph®, version 5.6, USA) available. Nine participants who did not provide sufficient data during the initial monitoring used the accelerometer in the second week to ensure that the minimum data requirements were met. The data were collected at a sampling rate of 80Hz, downloaded at intervals of 1s, and then aggregated in periods of 15s.17

This study used the calculation of counts for the accelerometer cutoff points established by Evenson et al.17 for periods of 15s. Specifically, for data calculation, the cutoff points of ≤25 counts/15s for sedentary time and ≥574 counts/15s for MVPA were used.17 Cutoff points capture the sporadic nature of children's activities and provide the best accuracy of classification among the currently available cutoff points for physical activity in children.15

Body compositionThe body composition variables included in the study were height, body mass, and BMI. A battery of anthropometric measurements was performed according to standardized procedures.8 Height was measured without shoes, using a portable Seca 213 stadiometer (Seca®, Hamburg, Germany), with the head in the Frankfurt plane. Body mass was measured using a Tanita SC-240 scale, a portable body composition analyzer (Tanita®, USA), after the children removed heavy items from the pockets, as well as shoes and socks.2 Two measurements were obtained, and the mean was used in the analysis (the third measurement was obtained if the first two measurements had a difference greater than 0.5kg or 2.0% of the body weight).

BMI (kg/m2) was calculated based on the height and body weight and, subsequently, the z-score was calculated based on the growth reference data of the World Health Organization (WHO). Children were classified as: normal weight: <+1SD; overweight >+1SD to 2SD; and obese: >+2SD.18

CovariatesA parent or legal guardian was asked to complete the Neighborhood and Home Environment Questionnaire, which included questions related to the child's health history and annual family income; the questions were asked separately to the parents.8 The annual family income (R$) was used as a measure of socioeconomic levels and classified into eight categories that represent increasing levels of income, so that the families with lower income were classified in the first category, and those with higher income were classified in the highest category. Due to the variability in socioeconomic status between public and private schools, the multivariate analysis was adjusted for the school type.

Statistical analysisA descriptive analysis was calculated, including mean, standard deviation (SD) frequency and percentage (%), and the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to assess data distribution. Student's t-test was performed to compare the means of continuous variables (sedentary time, MVPA, and BMI) with the presence or absence of each electronic device in the children's bedrooms.19

In the analysis, the total number of electronic devices in the children's bedrooms was also grouped into none, one, two, or three. The comparison between the total number of electronic devices in the bedroom (none, one, two, or three) with the means of continuous variables was performed by analysis of variance with one factor, followed by the Bonferroni multiple comparisons method.

The multiple linear regression analysis, using the “Enter” method, was performed to assess the association between electronic equipment in the bedroom with sedentary time, MVPA, and BMI, adjusted for gender, school, and annual family income. The Statistical Analysis System (SAS Institute Inc., USA) was used for the analysis, and p<0.0519 was considered significant.

ResultsOf the 441 children, 216 (49%) were boys, and most had a TV (326; 73.9%) and a computer in the bedroom (239; 54.2%). As for videogames, 189 (42.8%) of the children had them in the bedroom. The mean sedentary time and MVPA was 500.7 and 59.1min/day, respectively (Table 1).

Descriptive characteristics (mean [SD] or n [%]) of electronic equipment, sedentary time, MVPA, BMI, and children's family annual household income.

| Mean (SD) or n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Gender (n=441) | |

| Boys | 216 (49%) |

| Girls | 225 (51%) |

| TV in the bedroom (n=441) | 326 (73.9%) |

| Computer in the bedroom (n=441) | 239 (54.2%) |

| Videogames in the bedroom (n=441) | 189 (42.8%) |

| Accelerometry (n=441) | |

| Sedentary time (min/day) | 500.7 (66.6) |

| MVPA (min/day) | 59.1 (25.7) |

| BMI (kg/m2; n=441) | 19.8 (4.5) |

| BMI categories (WHO cutoff18; n=441) | |

| Normal weight | 241 (54.7%) |

| Overweight | 102 (23.1%) |

| Obese | 98 (22.2%) |

| Annual family income (n=382) | |

| 8 (2.1%) | |

| R$ 6540.00–19620.00 | 138 (36.1%) |

| R$ 19620.01–32700.00 | 101 (26.4%) |

| R$ 32700.01–45780.00 | 49 (12.8%) |

| R$ 45780.01–58860.00 | 32 (8.4%) |

| R$ 58860.01–71940.00 | 24 (6.3%) |

| R$ 71940.01–85020.00 | 16 (4.2%) |

| >R$ 85020.01 | 14 (3.7%) |

MVPA, moderate-to-vigorous physical activity; min, minutes. BMI, body mass index; WHO, World Health Organization; R$, Brazilian real.

Mean BMI was 19.8kg/m2. Based on the cutoff points proposed by WHO,18 54.7% of children had normal weight, 23.1% were overweight, and 22.2% were obese (45.3% of children were overweight/obese).

Regarding the annual family income, most of the families had income levels of R$ 6540.00–19620.00 (138; 36.1%) or R$ 19620.01–32700.00 (101; 26.4%) per year.

Table 2 shows that there was no significant difference between the means of sedentary time with the presence or absence of electronic equipment in the bedroom, both in the entire sample and by gender.

Descriptive analysis (mean and SD) of sedentary time, MVPA, and BMI according to the presence or absence of electronic equipment in the children's bedroom.

| TV | Computer | Videogames | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | pa | Yes | No | pa | Yes | No | pa | ||

| Sedentary time (min/day) | Total | 501.4 (69.4) | 497.9 (63.8) | 0.616 | 504.6 (72.2) | 495.0 (62.0) | 0.130 | 500.6 (66.8) | 501.3 (66.8) | 0.905 |

| Boys | 491.7 (72.6) | 493.4 (64.3) | 0.870 | 494.1 (73.5) | 488.4 (65.8) | 0.545 | 494.8 (69.3) | 491.2 (66.2) | 0.707 | |

| Girls | 510.7 (65.0) | 502.2 (63.5) | 0.381 | 515.3 (69.6) | 501.0 (58.0) | 0.094 | 513.9 (59.1) | 506.5 (66.7) | 0.429 | |

| MVPA (min/day) | Total | 58.4 (26.4) | 61.1 (23.8) | 0.294 | 57.3 (25.8) | 61.2 (25.7) | 0.117 | 55.4 (27.2) | 64.1 (24.0) | <0.001b |

| Boys | 70.4 (28.3) | 71.0 (24.6) | 0.878 | 69.6 (26.1) | 72.0 (29.0) | 0.512 | 68.1 (26.6) | 72.2 (28.5) | 0.283 | |

| Girls | 46.8 (18.0) | 51.6 (18.7) | 0.091 | 45.0 (18.8) | 51.4 (17.2) | 0.009b | 49.0 (17.9) | 45.4 (18.4) | 0.188 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | Total | 19.9 (4.5) | 19.2 (4.0) | 0.102 | 20.1 (4.8) | 19.3 (3.9) | 0.054 | 20.1 (4.9) | 19.4 (3.9) | 0.100 |

| Boys | 20.0 (4.9) | 19.2 (4.0) | 0.185 | 20.4 (5.4) | 19.2 (3.5) | 0.030b | 20.0 (5.0) | 19.4 (3.8) | 0.325 | |

| Girls | 19.8 (4.2) | 19.2 (4.1) | 0.327 | 19.7 (4.2) | 19.5 (4.3) | 0.609 | 20.3 (4.7) | 19.4 (4.0) | 0.178 | |

TV, television; MVPA, moderate-to-vigorous physical activity; BMI, body mass index.

For the mean MVPA, no significant difference was found regarding the presence or absence of TV in the bedroom. Regarding the presence of a computer in the bedroom, there was no significant difference between the means of MVPA in the entire sample or in boys. Regarding the girls, those that did not have a computer in the bedroom performed a mean of 6.4min/day of MVPA more than those with a computer in the bedroom (p=0.009). As for the presence or absence of videogames in the bedroom, there was significant difference between the means of MVPA (p<0.001). Those who did not have videogames in the bedroom performed 8min/day more MVPA than those who did.

No significant difference was found in mean BMI with the presence or absence of TV in the bedroom. Boys who had a computer in the bedroom had on average 1.2kg/m2 greater BMI than those who had no computer in the bedroom (p=0.030). The means of BMI showed no differences whether the children had or did not have videogames in the bedroom (Table 2).

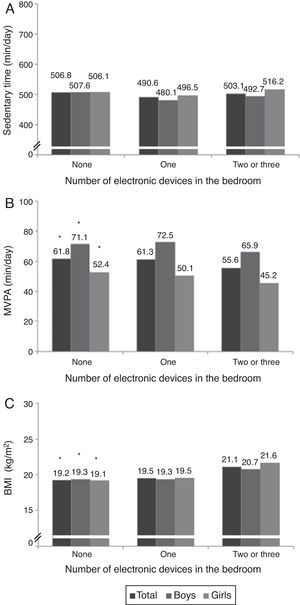

Fig. 1 shows that there was no significant difference between the means of sedentary time with the number of electronic devices in the children's bedroom, both in the entire sample and by gender.

Mean sedentary time (A), MVPA (B), and BMI (C) according to the number of electronic equipment devices in the children's bedroom. Analysis of variance with one factor followed by Bonferroni method (p<0.05). MVPA, moderate-to-vigorous physical activity; BMI, body mass index. *Difference between none and two or three electronic equipment devices. n=77 (no electronic equipment); n=111 (one electronic devices); n=253 (two or three electronic devices).

For the mean MVPA, there was significant difference between none and two or three electronic devices in the bedroom, both in the entire sample and by gender. When considering both genders, children who had no electronic devices in the bedroom performed on average (6.2min/day) more MVPA than those who had two or three electronic devices. For boys, the MVPA difference was 5.2min/day and for girls, 7.2min/day.

For BMI, a significant difference was found between the means according to the number of electronic devices in the bedroom. Children who had no electronic devices in the bedroom had lower mean BMI than those who had two or three electronic devices in the bedroom.

For the entire sample, Table 3 shows the results of the multivariate regression analysis, adjusted for gender, school, and annual family income, describing the association between the presence of electronic equipment in the bedroom with sedentary time, MVPA, and BMI. There was no significant association between any of the electronic equipment units, even when combined in the multivariate analysis with sedentary time.

Adjusted analysis between electronic equipment in the bedroom and sedentary time, MVPA, and BMI of children.

| Electronic equipment in the bedroom | Sedentary time | MVPA | BMI (kg/m2) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β coefficient | 95% CI | pa | β coefficient | 95% CI | pa | β coefficient | 95% CI | pa | |

| TV | 5.289 | −10.248, 20.825 | 0.504 | −3.240 | −8.634, 2.155 | 0.238 | 0.838 | −0.138, 1.815 | 0.092 |

| Computer | 8.157 | −5.394, 21.708 | 0.237 | −4.798 | −9.508, −0.088 | 0.046b | 0.804 | −0.058, 1.666 | 0.068 |

| Videogames | 5.920 | −8.357, 20.196 | 0.415 | −0.008 | −5.081, 5.065 | 0.997 | 0.943 | 0.038, 1.849 | 0.041b |

| TV+PC | 4.100 | −4.768, 12.967 | 0.364 | −3.233 | −6.337, −0.128 | 0.041b | 0.661 | 0.097, 1.224 | 0.022b |

| TV+VG | 4.094 | −4.816, 13.005 | 0.367 | −1.377 | −4.510, 1.757 | 0.388 | 0.625 | 0.073, 1.178 | 0.027b |

| PC+VG | 5.340 | −3.228, 13.908 | 0.221 | −2.135 | −5.146, 0.876 | 0.164 | 0.656 | 0.117, 1.194 | 0.017b |

| TV+PC+VG | 3.620 | −2.785, 10.024 | 0.267 | −1.796 | −4.044, 0.452 | 0.117 | 0.521 | 0.118, 0.925 | 0.011b |

MVPA, moderate-to-vigorous physical activity; BMI, body mass index; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; TV, television; PC, personal computer; VG, videogames.

The presence of a computer in the bedroom and the combination of TV and computer were negatively associated with MVPA. For all other items of electronic equipment, there was no significant association with MVPA (Table 3).

A significant positive association was found for videogames and the combination of two or three electronic devices in the bedroom with the children's BMI (Table 3).

DiscussionThe aim of this study was to describe the association between electronic equipment in the bedroom with sedentary time and physical activity, both assessed by accelerometry, in addition to BMI in children of São Caetano do Sul. The results demonstrated that children spend 500.7min/day of sedentary time and 59.1min/day of MVPA, and 45.3% had overweight/obesity. The presence of electronic equipment in the bedroom was negatively associated with MVPA. In addition, the presence of videogames and combinations with two or three electronic devices in the bedroom were positively associated with children's BMI.

This study confirms previous studies, which showed a negative association between electronic equipment in the children's bedroom with MVPA, evaluated by an accelerometer.20,21 For instance, in a study with children in the United States, O’Connor et al.,21 using a different cutoff point (≥2296 counts/min) from that used in the present study (≥574 counts/15s) to classify MVPA, found a negative association (β=−2.33) between the presence of electronic equipment (TV, computer, videogames, and DVD player) in the children's bedroom with MVPA.

The present study found a negative association between the presence of the computer (β=−4.798) and the combination of TV and computer (β=−3.233) in the children's bedroom with MVPA. Because some other studies9,11 did not find a significant association between electronic equipment in the bedroom with MVPA, conflicting research results must occur due to individual behavioral differences, including children with “less healthy” behaviors and healthier behaviors, in order to maintain the energy balance of the body and body mass.11

Although the present study did not show an association between the presence of electronic equipment in the bedroom with sedentary time, studies in developed countries such as Canada11 and the United Kingdom9 showed similar results to this study. In a study that was part of the SPEEDY trial, Atkin et al.9 found that the presence of electronic equipment in the bedroom was not associated with sedentary time (defined as <100 counts/min). Some researchers22,23 suggest that TV viewing, for instance, can be a general indicator of sedentary lifestyle and might be only an indicator of the total time of sedentary behavior.24,25

The present results are in agreement with previous studies showing that the presence of at least two electronic equipment units in the children's bedroom is associated with increased risk of excess weight.11,26 For example, analyzing the ISCOLE data from Canada and the applying same methodology regarding measures and tools of the present study, Chaput et al.11 used the percentage of body fat to estimate excess weight. The authors analyzed the same electronic devices assessed in this study and found a negative association with body fat percentage. Children with two or three electronic devices in the bedroom had higher mean values of body fat than those who did not have electronic devices in the bedroom (24.5% versus 20%).

As accelerometry requires a combination of financial resources and technological knowledge, it has challenged researchers from developing countries. In several previous studies, Brazilian researchers based their studies on questionnaires to quantify the sedentary time and physical activity, concentrating only on the amount of time spent in front of electronic devices, especially TV.27–29 This is the first Brazilian study to suggest that the presence of one or more electronic devices in the bedroom is associated with MVPA and BMI.

The authors believe that the strengths of this study include the objective measures of sedentary time and MVPA, as their respective techniques and approaches are rare in Brazil, considering that the majority of previous studies used questionnaires and indirect measures to assess physical activity.29,30 This study increases the knowledge of the existing literature on the association between sedentary time and MVPA, assessed by accelerometry with the presence of electronic equipment in the children's bedroom. Although it provides accelerometry data, it has some limitations: the cross-sectional design prevents the establishment of cause-and-effect associations and the lack of representativeness of the sample prevents data extrapolation to Brazilian children.

This study provides evidence of associations between the presence of electronic equipment in the bedroom with MVPA and BMI, regardless of gender, school, and annual family income. Particularly, two or three electronic devices in the bedroom are associated with low MVPA and high BMI. No significant association between electronic equipment in the bedroom and sedentary time was found.

FundingThe ISCOLE Brazil research project was funded by the Coca-Cola Company. The funder had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or manuscript preparation.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The authors would like to thank the participants, parents and/or guardians, teachers, and coordinators of Municipal Secretariat of Education of São Caetano do Sul and the Town Hall of São Caetano do Sul.

Please cite this article as: Ferrari GL, Araújo TL, Oliveira LC, Matsudo V, Fisberg M. Association between electronic equipment in the bedroom and sedentary lifestyle, physical activity, and body mass index of children. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2015;91:574–82.