To estimate the association between the implementation of the Brazilian Breastfeeding Network and prevalence of breastfeeding in a medium-size city in southern Brazil.

MethodsThis was a cross-sectional study involving 405 children under 1 year who participated in the second phase of the multivaccination campaign in 2012. Children's consumption of food on the day before the interview was obtained through interviews with mothers or guardians. The manager and one health professional from every health facility that joined the Network were interviewed in order to investigate the process of implementation of this initiative. The association between prevalence of breastfeeding and exclusive breastfeeding and adherence to the Network implementation process was tested using Poisson regression with robust variance.

ResultsMultivariate analysis revealed that among the children assisted by health facilities who joined the Network and those attending services that did not adhere to this strategy, the prevalence of breastfeeding (74% and 70.4% among children under 1 year, respectively) and exclusive breastfeeding (43.3% and 38.1% among children under 6 months, respectively) did not differ significantly. Difficulties in implementing the Network, such as high turnover of professionals, not meeting the criteria for accreditation, and insufficient participation of tutors in the process were identified.

ConclusionContrary to the hypothesis of this study, there was no significant association between the implementation of the Brazilian Breastfeeding Network and prevalence of breastfeeding and exclusive breastfeeding in the studied city. It is possible that the difficulties found in implementing the Network in this city have influenced this result.

Estimar a associação entre a implementação da Rede Amamenta Brasil e as prevalências de aleitamento materno (AM) em um município de médio porte do sul do Brasil.

MétodosEstudo transversal envolvendo 405 crianças menores de um ano que participaram da segunda fase da campanha de multivacinação de 2012. O consumo de alimentos pela criança no dia anterior à entrevista foi obtido mediante entrevistas com as mães ou responsáveis. Para investigar o processo de implementação da Rede foram entrevistados o gerente e um profissional de saúde de cada unidade que aderiu a esse processo. A associação entre as prevalências de AM e AM exclusivo (AME) e a adesão ao processo de implementação da Rede foi testada utilizando-se regressão de Poisson com variância robusta.

ResultadosA análise multivariada revelou que, entre as crianças assistidas por unidades que aderiram ao processo de implementação da Rede e as que frequentavam serviços que não aderiram a essa estratégia, as prevalências de AM (74% e 70,4% em menores de um ano, respectivamente) e AME (43,3% e 38,1% em menores de seis meses, respectivamente) não diferiram significativamente. Foram identificadas dificuldades na implementação da Rede, tais como alta rotatividade dos profissionais, não cumprimento dos critérios para certificação e acompanhamento insuficiente das unidades pelos tutores da Rede.

ConclusãoContrariando a nossa hipótese, não houve associação significativa entre a implementação da Rede Amamenta Brasil e as prevalências de AM e AME no município estudado. É possível que as dificuldades encontradas na implementação da Rede nesse município tenham influenciado esse resultado.

Brazil has shown progress on indicators of breastfeeding (BF) since the 1980s, due to the efforts of the government, non-governmental organizations, universities, and the media, among others.1 However, these indicators are still not adequate. According to the National Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) carried out in 2006, the median duration of exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) and BF was 1.4 months and 14 months, respectively,2 indicating the need for strategies that promote EBF in the first 6 months of the child's life and complemented BF up to 2 years of age or more.

Until recently, policies for the promotion, protection, and support of BF in Brazil were focused on hospital care, including the adoption of the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative and kangaroo care, and the creation of the Brazilian Network of Human Milk Banks. Aiming to meet the lack of BF incentive actions in primary care, the Ministry of Health launched the Brazilian Breastfeeding Network [Rede Amamenta Brasil] in 2008, aiming to mobilize health professionals working at this attention level, using critical-reflexive methodology.

This strategy included conducting a workshop lasting six hours with the entire staff of the health unit, with the participation of at least one professional from each functional category, including administrative and outsourced personnel, during which the process of working towards the promotion, protection, and support of BF was discussed, exposing difficulties and agreeing on actions while seeking solutions based on the local reality.3 It also provided for the support of the health unit though regular visits of a Network tutor, trained to encourage and support the service in the promotion, protection, and support of BF in their coverage area.

For the unit to be certified, it had to meet the following criteria: participation of at least 80% of staff in the workshop; continuous monitoring of BF indicators in its coverage area; completion of at least one action agreed upon at the workshop; and implementation of the care flow chart for both mother and child during the BF period.4

Since its implementation, several cities in different regions of Brazil have joined the Brazilian Breastfeeding Network (currently known as the Brazilian Breastfeeding and Feeding Strategy [Estratégia Amamenta e Alimenta Brasil], after integration with the National Strategy for the Promotion of Healthy Complementary Feeding [Estratégia Nacional de Promoção da Alimentação Complementar Saudável–ENPACS] in 2011), resulting in health care facilities with a different status regarding this strategy. As to date this strategy has not had its results evaluated, it was deemed appropriate to carry out this study, aimed to estimate the association between the implementation of this strategy and the prevalence of BF and EBF in a city in southern Brazil. The initial hypothesis was that populations assisted by health services that joined the Brazilian Breastfeeding Network implementation process would show better indicators of BF.

MethodsThis was a cross-sectional study conducted in Bento Gonçalves, a municipality in the mountainous region of Rio Grande do Sul, with a population of 107,341 inhabitants, Gini index of 0.45, Human Development Index of 0.87, coefficient of infant mortality of 14.1 per 1,000 live births, and non-public health insurance coverage of 41.7%.5,6 In the year 2011, 1,274 births occurred in the city.6

Bento Gonçalves currently has 22 primary health care facilities (PHCF) and a maternal-child reference center (MCRC). The process of implementing the Brazilian Breastfeeding Network in the city was started in October 2009, with six PHCF having been certified by the Ministry of Health until the time of data collection, in addition to the MCRC, totaling seven certified health services. During this period, 14 other PHCF started the Network implementation process and had the workshop, but were not certified. Two of the 22 PHCF and all private health services or health services funded by non-public health insurance companies were not exposed to any action by the Brazilian Breastfeeding Network.

To characterize the services that adhered to the process of the Brazilian Breastfeeding Network implementation regarding the status of this strategy, the researchers performed interviews with 21 managers and 20 health professionals with higher education from these units. At that time, information was collected on the verification of compliance with the four criteria required for the BHU's certification with the Network, on participation of tutor in the process through visits to the unit, and care provided for mothers and babies, including the use of protocols and flow charts, clinical management, and counseling. For these interviews, the same research questionnaires used for the analysis of the implementation of the Brazilian Breastfeeding Network were utilized.3 These data allowed for a comparison between the services certified by the Ministry of Health, i.e., the ones that met the certification criteria at the time they were assessed, and those that had initiated the Network implementation process with the workshop performance, but that had not yet been certified by the Ministry of Health at the time of data collection.

To estimate the prevalence of EBF and BF in the study population, this study aimed to include all children younger than 1 year who came to the PHCF on the day assigned for the vaccination against polio during the 2012 vaccination campaign. This methodology has been widely used in Brazil, bringing important contributions to the analysis of the BF situation in the country, and helping to formulate policies and plan actions.7 Considering that the municipality initiated this campaign in public and private preschools in the week prior to vaccination day, data collection was extended to these locations. To prevent the same child from participating twice in the study, the children's data were verified to detect any duplication.

To test the sample representativeness, the characteristics of the children included in the study were compared with those of children younger than 1 year in the municipality, using data from the Live Birth Information System (Sistema de Informação sobre Nascidos Vivos [SINASC]), related to births in 2011. For that purpose, the chi-squared test with Yates correction was performed and the significance level was set at p<0.05.

The data collection tool was based on the questionnaire used in the II Breastfeeding Prevalence Survey (Pesquisa de Prevalência de Aleitamento Materno [PPAM]) and contained seven questions on consumption of breast milk, other kinds of milk, and other foods, including water, teas, and other liquids on the day before the interview, following the WHO recommendations for BF surveys.7 In addition to the dietary survey, the questionnaire included questions related to the health service the child used to monitor growth and development, including public, funded by non-public health insurance companies and private health services. Data were collected by 40 properly trained interviewers recruited from health services and technical and higher education courses of the region, distributed in 25 vaccination units throughout the city, including all PHCF.

To characterize the dietary habits, the following definitions were considered: EBF when the child received only breast milk without any other food, solid or liquid, except medications; and BF, when the child received breast milk, regardless of whether she received other foods or not, including liquids.8

Stata 11.0 software (StataCorp LP, TX, USA) was used for the database and statistical analysis. Descriptive analysis was performed by calculating means and standard deviations of quantitative variables and simple frequency of qualitative variables. The comparison of the prevalence of EBF and BF according to follow-up location was performed using the Yates-corrected chi-squared test, using a significance level of 0.05.

To test the association between the child's place of follow-up and BF indicators, Poisson regression with robust variance was used, taking into account variables which, according to the literature, could be interfering with the results. Initially simple regressions were used, considering the dependent variable and each of the following independent variables: child's age; mother's age, parity, and educational level; cohabitation with the child's father and grandmother; area of residence (urban or rural); type of delivery; BF in the first hour after birth; problems with BF; time that the mother spends with the child; and pacifier use.

Independent variables with p<0.20 were selected for the multivariate model, with the exception of maternal education and age, as they have been considered relevant factors in other studies9,10 and because they showed a significant difference in sample distribution. Significance level was set at p<0.05 for the multiple regression model. Stata 11.0 software was used for the database and statistical analysis.

This study was approved by the Municipal Health Secretariat of Bento Gonçalves and by the Research Ethics Committee of Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul. All respondents signed the informed consent.

ResultsOf the 20 PHCF that held the workshop, 45% (n=9) belong to the Family Health Strategy (FHS), 30% (n=6) do not perform child care follow-up, and 40% (n=8) do not perform prenatal care. Regarding the certified facilities, all PHCF except the MCRC belong to the FHS.

The workshops in the health services that initiated the Network implementation process were carried out on average 24 months before the performance of this study for those that were certified (SD=6.17) and 17 months for the non-certified (SD=4.16).

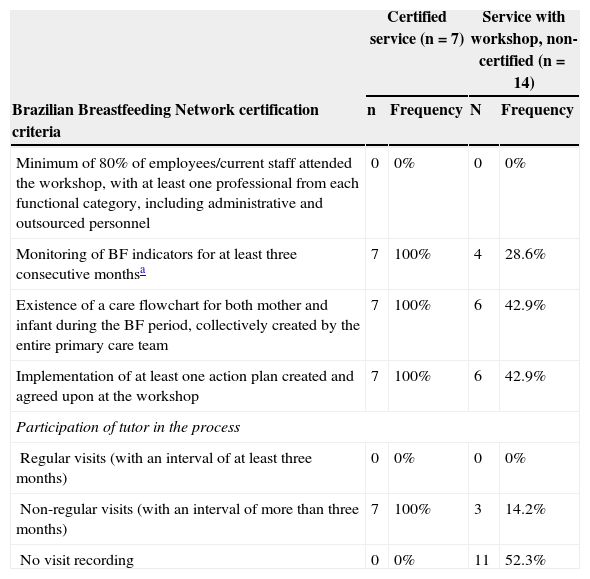

The characterization of health services according to the adequacy of the criteria for certification and monitoring of the unit at the time of data collection is shown in Table 1.

Characterization of health services according to the criteria for Brazilian Breastfeeding Network certification and participation of tutors - Bento Gonçalves, 2012.

| Certified service (n=7) | Service with workshop, non-certified (n=14) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brazilian Breastfeeding Network certification criteria | n | Frequency | N | Frequency |

| Minimum of 80% of employees/current staff attended the workshop, with at least one professional from each functional category, including administrative and outsourced personnel | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| Monitoring of BF indicators for at least three consecutive monthsa | 7 | 100% | 4 | 28.6% |

| Existence of a care flowchart for both mother and infant during the BF period, collectively created by the entire primary care team | 7 | 100% | 6 | 42.9% |

| Implementation of at least one action plan created and agreed upon at the workshop | 7 | 100% | 6 | 42.9% |

| Participation of tutor in the process | ||||

| Regular visits (with an interval of at least three months) | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| Non-regular visits (with an interval of more than three months) | 7 | 100% | 3 | 14.2% |

| No visit recording | 0 | 0% | 11 | 52.3% |

It was found that 47.5% (n=153) of the 322 health professionals who were working at the time of data collection in the 21 services that started the process of implementing the Brazilian Breastfeeding Network joined the unit after completion of the workshop and that other workshops were not offered for new employees until then. Approximately one-quarter of the 41 professionals interviewed (26.8%) were unaware of the existence of the care flowchart for both mother and baby during BF. Regarding the use of BF management protocols, this study verified the absence of use of such protocols in 95.2% of units (n=20).

Information was obtained on BF, EBF, and place of growth and development monitoring of 405 children younger than 1 year, representing 31.7% of the population younger than 1 year living in the city. Of these, 191 (47.2%) were followed in the primary care network of the Brazilian Unified Health System (Sistema Único de Saúde [SUS]) and 214 (52.8%) in private/funded by non-public health insurance companies health services. Of all children evaluated, 181 (94 of whom were younger than 6 months) were followed in units that joined the implementation of the Brazilian Breastfeeding Network and 224 (102 younger than 6 months) at services that did not adhere to this strategy.

With this sample, to study the association between implementation of the Brazilian Breastfeeding Network and prevalence of BF and EBF, with a confidence level of 95% and a study power of 80%, it would be possible to detect differences of approximately 12% in the prevalence of BF in children younger than 1 year and 14% in the prevalence of EBF in children younger than 6 months, starting from the prevalence rates found in the population not exposed to the Network implementation (38% for EBF and 70% for BF).

When the sample was compared with the universe of children younger than 1 year in the city, there was no statistically significant difference regarding gender, type of birth, and maternal education level. However, there were differences regarding the mother's age. The sample had a lower frequency of adolescent mothers (6.3% versus 10.6% in the reference population, p=0.03).

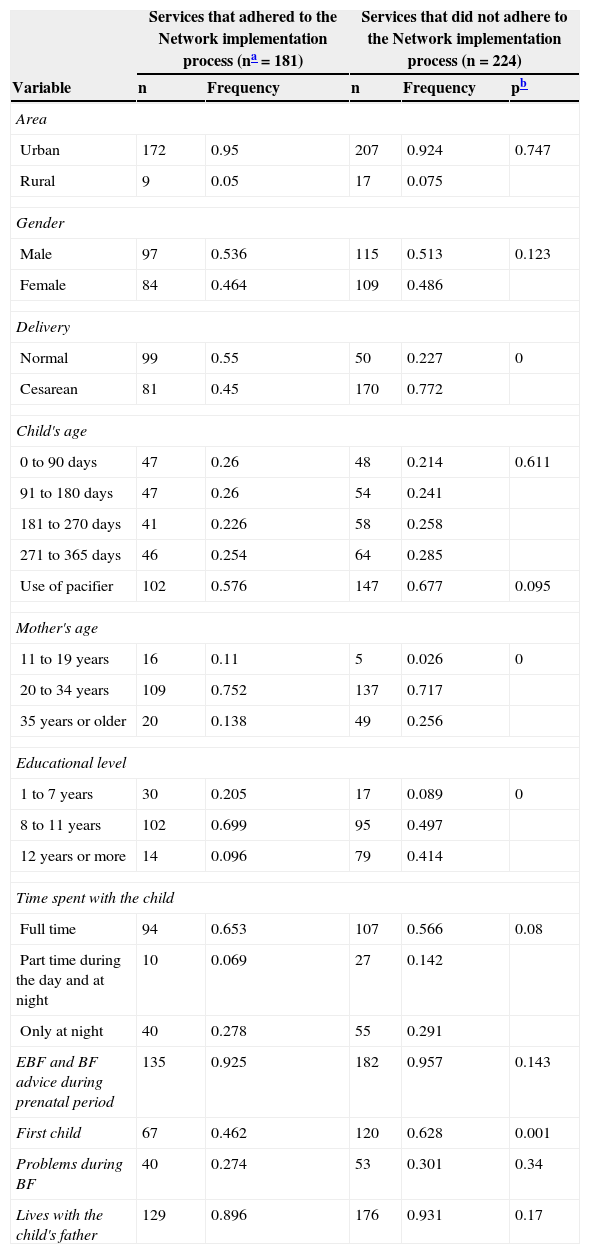

Table 2 shows the characteristics of the sample, according to the service where the children were followed. Among those followed in services where there was no implementation of the Brazilian Breastfeeding Network, there was a higher proportion of children born by cesarean section, to mothers older than 35 years, mothers with educational level equal to or greater than 12 years of schooling, and primiparous women.

Characteristics of the children younger than 1 year, according to adherence to the Brazilian Breastfeeding Network implementation process, in the services where their growth and development were monitored - Bento Gonçalves, 2012.

| Services that adhered to the Network implementation process (na=181) | Services that did not adhere to the Network implementation process (n=224) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | n | Frequency | n | Frequency | pb |

| Area | |||||

| Urban | 172 | 0.95 | 207 | 0.924 | 0.747 |

| Rural | 9 | 0.05 | 17 | 0.075 | |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 97 | 0.536 | 115 | 0.513 | 0.123 |

| Female | 84 | 0.464 | 109 | 0.486 | |

| Delivery | |||||

| Normal | 99 | 0.55 | 50 | 0.227 | 0 |

| Cesarean | 81 | 0.45 | 170 | 0.772 | |

| Child's age | |||||

| 0 to 90 days | 47 | 0.26 | 48 | 0.214 | 0.611 |

| 91 to 180 days | 47 | 0.26 | 54 | 0.241 | |

| 181 to 270 days | 41 | 0.226 | 58 | 0.258 | |

| 271 to 365 days | 46 | 0.254 | 64 | 0.285 | |

| Use of pacifier | 102 | 0.576 | 147 | 0.677 | 0.095 |

| Mother's age | |||||

| 11 to 19 years | 16 | 0.11 | 5 | 0.026 | 0 |

| 20 to 34 years | 109 | 0.752 | 137 | 0.717 | |

| 35 years or older | 20 | 0.138 | 49 | 0.256 | |

| Educational level | |||||

| 1 to 7 years | 30 | 0.205 | 17 | 0.089 | 0 |

| 8 to 11 years | 102 | 0.699 | 95 | 0.497 | |

| 12 years or more | 14 | 0.096 | 79 | 0.414 | |

| Time spent with the child | |||||

| Full time | 94 | 0.653 | 107 | 0.566 | 0.08 |

| Part time during the day and at night | 10 | 0.069 | 27 | 0.142 | |

| Only at night | 40 | 0.278 | 55 | 0.291 | |

| EBF and BF advice during prenatal period | 135 | 0.925 | 182 | 0.957 | 0.143 |

| First child | 67 | 0.462 | 120 | 0.628 | 0.001 |

| Problems during BF | 40 | 0.274 | 53 | 0.301 | 0.34 |

| Lives with the child's father | 129 | 0.896 | 176 | 0.931 | 0.17 |

EBF, exclusive breastfeeding; BF, breastfeeding.

The EBF prevalence in children younger than 6 months was 38.8%, with a median duration of 54.5 days. The prevalence of BF among infants younger than 1 year was 71.9%, with a median duration of 157 days. If only the private/funded by non-public health insurance companies care network is considered, these rates were 36.2% and 70.1%, respectively.

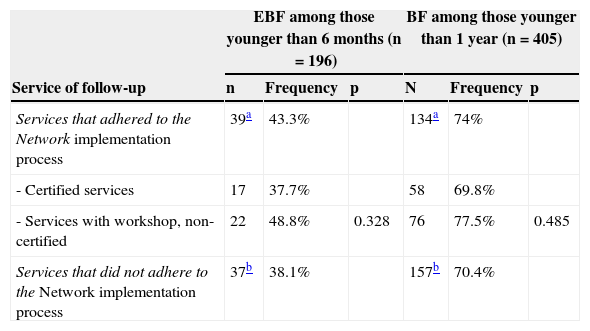

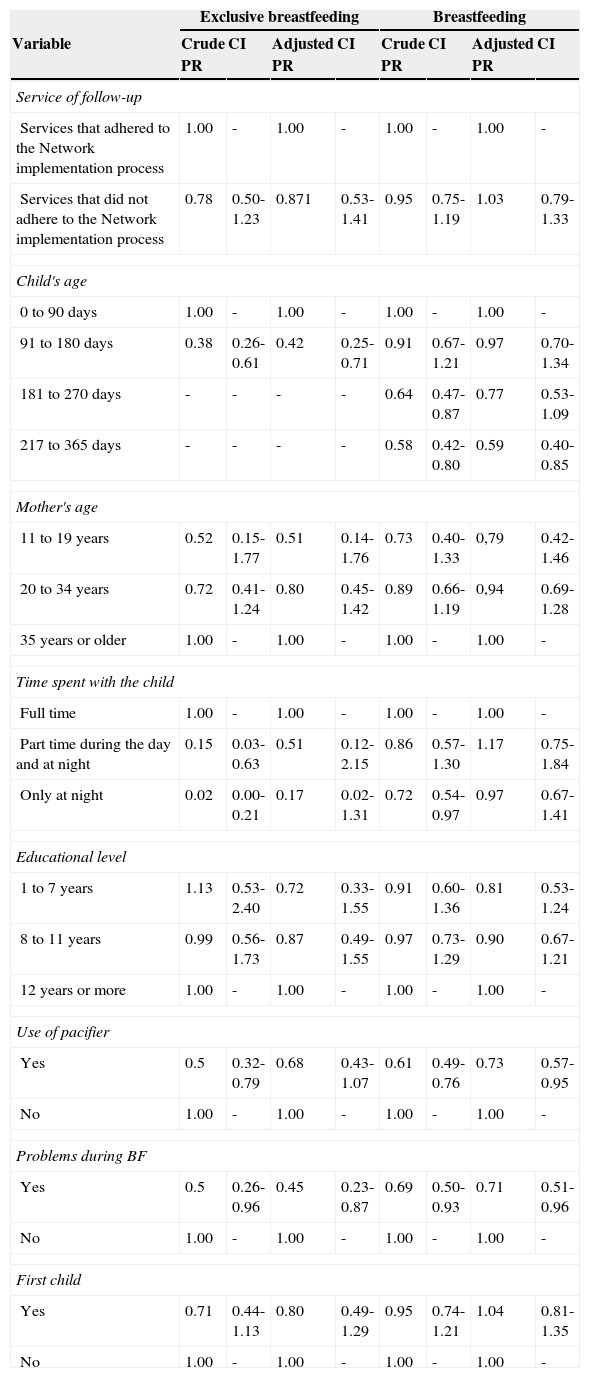

Table 3 shows the prevalence of EBF and BF according to place of follow-up. The bivariate analysis showed no statistically significant differences in the prevalence of EBF and BF among children followed at units that joined the Brazilian Breastfeeding Network (certified or undergoing the certification process) and those attending services that did not join the Network. This result was confirmed in the analysis of Poisson regression with robust variance and crude and adjusted PR (Table 4).

Prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding and breastfeeding according to the service of child follow-up - Bento Gonçalves, 2012.

| EBF among those younger than 6 months (n=196) | BF among those younger than 1 year (n=405) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Service of follow-up | n | Frequency | p | N | Frequency | p |

| Services that adhered to the Network implementation process | 39a | 43.3% | 134a | 74% | ||

| - Certified services | 17 | 37.7% | 58 | 69.8% | ||

| - Services with workshop, non-certified | 22 | 48.8% | 0.328 | 76 | 77.5% | 0.485 |

| Services that did not adhere to the Network implementation process | 37b | 38.1% | 157b | 70.4% | ||

EBF, exclusive breastfeeding; BF, breastfeeding.

Result of the multivariate analysis when testing the association between prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) in children younger than 6 months and breastfeeding (BF) in children younger than 1 year and services of child follow-up according to adherence to the Brazilian Breastfeeding Network - Bento Gonçalves, 2012.

| Exclusive breastfeeding | Breastfeeding | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Crude PR | CI | Adjusted PR | CI | Crude PR | CI | Adjusted PR | CI |

| Service of follow-up | ||||||||

| Services that adhered to the Network implementation process | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - |

| Services that did not adhere to the Network implementation process | 0.78 | 0.50-1.23 | 0.871 | 0.53-1.41 | 0.95 | 0.75-1.19 | 1.03 | 0.79-1.33 |

| Child's age | ||||||||

| 0 to 90 days | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - |

| 91 to 180 days | 0.38 | 0.26-0.61 | 0.42 | 0.25-0.71 | 0.91 | 0.67-1.21 | 0.97 | 0.70-1.34 |

| 181 to 270 days | - | - | - | - | 0.64 | 0.47-0.87 | 0.77 | 0.53-1.09 |

| 217 to 365 days | - | - | - | - | 0.58 | 0.42-0.80 | 0.59 | 0.40-0.85 |

| Mother's age | ||||||||

| 11 to 19 years | 0.52 | 0.15-1.77 | 0.51 | 0.14-1.76 | 0.73 | 0.40-1.33 | 0,79 | 0.42-1.46 |

| 20 to 34 years | 0.72 | 0.41-1.24 | 0.80 | 0.45-1.42 | 0.89 | 0.66-1.19 | 0,94 | 0.69-1.28 |

| 35 years or older | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - |

| Time spent with the child | ||||||||

| Full time | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - |

| Part time during the day and at night | 0.15 | 0.03-0.63 | 0.51 | 0.12-2.15 | 0.86 | 0.57-1.30 | 1.17 | 0.75-1.84 |

| Only at night | 0.02 | 0.00-0.21 | 0.17 | 0.02-1.31 | 0.72 | 0.54-0.97 | 0.97 | 0.67-1.41 |

| Educational level | ||||||||

| 1 to 7 years | 1.13 | 0.53-2.40 | 0.72 | 0.33-1.55 | 0.91 | 0.60-1.36 | 0.81 | 0.53-1.24 |

| 8 to 11 years | 0.99 | 0.56-1.73 | 0.87 | 0.49-1.55 | 0.97 | 0.73-1.29 | 0.90 | 0.67-1.21 |

| 12 years or more | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - |

| Use of pacifier | ||||||||

| Yes | 0.5 | 0.32-0.79 | 0.68 | 0.43-1.07 | 0.61 | 0.49-0.76 | 0.73 | 0.57-0.95 |

| No | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - |

| Problems during BF | ||||||||

| Yes | 0.5 | 0.26-0.96 | 0.45 | 0.23-0.87 | 0.69 | 0.50-0.93 | 0.71 | 0.51-0.96 |

| No | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - |

| First child | ||||||||

| Yes | 0.71 | 0.44-1.13 | 0.80 | 0.49-1.29 | 0.95 | 0.74-1.21 | 1.04 | 0.81-1.35 |

| No | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - |

PR, prevalence ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Contrary to the authors’ hypothesis, there was no statistically significant difference in the prevalence of EBF and BF among children followed at services that joined the Brazilian Breastfeeding Network (certified and non-certified) and services that were not exposed to the strategy actions in the municipality of Bento Gonçalves.

This result may be related to the difficulties found in the network implementation in this city, such as discontinuity of compliance with the criteria for certification in the Brazilian Breastfeeding Network in units that had already been certified, due to high staff turnover; low degree of compliance with the criteria by most units that initiated the certification process in the Network, but had not yet been certified at the time of data collection; and lack of awareness by the professionals of the existence of the care flowchart for both mother and baby during BF in these units, even in those where it was established. Failure to use the BF management protocols, including by the certified units, may also have contributed to the lack of association between the implementation of the Brazilian Breastfeeding Network and BF indicators.

Although regular visits from the tutor trained to exercise this function is not a criterion for certification, the Ministry of Health, when proposing the creation of the Brazilian Breastfeeding Network, emphasized the importance of the participation of tutor in the implementation process for the success of the strategy, suggesting a minimum interval of three months between visits.4 It was observed that the city had difficulty following this routine follow-up, as no services were visited by the tutor quarterly. The visits occurred primarily in certified units, although at a greater interval than the recommended schedule of three months. Considering that the Brazilian Breastfeeding Network tutor has the role of encouraging and supporting the health unit in the promotion, protection, and support of BF, insufficient participation of tutors found in Bento Gonçalves may have substantially contributed to the lack of association between this strategy and the prevalence of BF.

Some difficulties found in the implementation of the Brazilian Breastfeeding Network in the study municipality had already been indicated in a study on the analysis of the implementation of the Brazilian Breastfeeding Network carried out in 2011 in three municipalities (Ribeirão Preto-SP, Corumba-MT, and Porto Alegre-RS), such as difficulty in maintaining the monitoring of indicators, high staff turnover, and lack of BF management protocols.3

It is important to mention that the prevalence of BF and EBF were similar among certified services and those that had had the workshop, but were not certified at the time of the research, with an even higher prevalence, although not statistically significant, of these indicators in non-certified units. The expectation was that BF indicators among children followed at certified services would be more favorable than in the others. This result reinforces the hypothesis of difficulties in the full implementation of the strategy as it was conceived and suggests the need to reassess the criteria adopted for certification and recertification.

The EBF prevalence in children younger than 6 months in the present study (38.8%) showed to be a little lower than the national prevalence found in the II Survey on Breastfeeding Prevalence (41%), but similar to that found in Porto Alegre, capital city of the state (38.2%)7 and in the National DHS carried out in 2006 (38.6%).2

The prevalence of BF in children younger than 12 months found in this study (68.5%) was slightly lower than the prevalence found in the same municipality in a study performed in 2008 (71.1%),11 suggesting no improvement in BF indicators with the implementation of the Brazilian Breastfeeding Network up to the time of this research. Although the purpose of this study was not to investigate factors associated to EBF and BF, it is emphasized that the factors found for both EBF (child's age and problems in the breast during BF) as well as for BF (child's age, pacifier use, and problems in the breast during BF) have been previously described in other studies.7,12–17

The limitations of the study may include an insufficient number of children to detect small differences in the prevalence of BF among the children followed at PCHF that joined and did not join the Network, as occurred in this study (5.2% for EBF and 3.6% for BF). Using classical sampling parameters (confidence level of 95% and study power of 80%), it would only be possible to detect differences greater than those found in this study, but that have been found in several more successful interventions in Brazil18,19 and other countries.20,21

The fact that there was a lower rate of adolescent mothers in the sample when compared with the population of children younger than 1 year in the municipality might overestimate the prevalence of EBF, considering that some studies show an association between young maternal age and lower prevalence of EBF.7,16 However, this characteristic was not associated with EBF or BF, and was incorporated into the multivariate analysis model, which minimizes this possible limitation. Another possibility of bias would be the fact that most of the infants followed in services that did not join the Brazilian Breastfeeding Network were followed in the non-public health system, attended by mothers with higher educational level.

The National DHS-20062 showed that the duration of EBF and BF among women with higher educational level is shorter, and the II Survey on Breastfeeding Prevalence in Brazilian Capital Cities7 confirmed this finding for BF, but showed opposite results for EBF. It is believed that this possible bias is small in the present study, as previous research carried out in the same municipality showed no association between prevalence of EBF and maternal educational level, family income, or service of prenatal care (SUS or not SUS).11

Additionally, the statistical model included the mother's educational level, thus minimizing a possible bias. As strong points of this study, the authors emphasize the fact that it was the first to evaluate the association between the implementation of the Brazilian Breastfeeding Network and the prevalence of BF in children younger than 1 year and EBF in those younger than 6 months in a Brazilian city. The only study on the effectiveness of this network performed up to now evaluated only the rates of EBF in children younger than 6 months in the city of Ribeirão Preto, in 2011.22

Several studies have shown that educational interventions to promote and support BF significantly improve BF indicators.23–27 Thus, a significant positive association would be expected between the implementation of the Brazilian Breastfeeding Network and a higher prevalence of BF and EBF, which did not occur. However, caution is needed when interpreting this result. The same strategy, when assessed in Ribeirão Preto, SP, showed positive results. In that city, the prevalence of EBF in children younger than 6 months was significantly higher (OR=1.41, 95% CI=1.01-1.95) among children followed in health facilities that performed the workshop of the Brazilian Breastfeeding Network.22

This result suggests that the Network can be an effective strategy to increase EBF rates. Moreover, as previously mentioned, several difficulties were observed when implementing the strategy in the municipality of the present study. These difficulties must be analyzed in the context of the current Brazilian health system: lack of material and human resources, excessive responsibilities of health professionals, lack of an attractive career plan to keep the professionals in their workplaces, and discontinuity of programs and adoption of new programs with new policy-makers, often resulting in demotivation of health professionals.

In this scenario, the implementation of the Brazilian Breastfeeding Network, as planned in the current health care model, becomes a challenge. The analysis of the implementation of the Network, conducted by the Ministry of Health in 2011, already showed low prioritization of the Network in state health plans, difficulties in the discussion process about its implementation at the municipal level, and competition with existing governmental projects and programs as hindering factors to the adherence and maintenance of the Network in healthcare facilities. This evaluation also showed that the good experiences regarding the implementation of this strategy were not related to isolated motivation or performance of individuals, but rather linked to an institutional project, with support from the municipal management.3

Thus, we believe that the inclusion of the promotion, protection and support of breastfeeding in the list of health priorities in the three governmental spheres (federal, state and municipal) and a reflection on the lack of association between the implementation of the Brazilian Breastfeeding Network and BF indicators described here may contribute for planning and strengthening of actions aimed at better feeding practices with impact on children's health.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Brandão DS, Venancio SI, Giugliani ER. Association between the Brazilian Breastfeeding Network implementation and breastfeeding indicators. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2015;91:143–51.