Identify associated factors for recurrent wheezing (RW) in male and female infants.

MethodsCross-sectional multicentric study using the standardized questionnaire from the Estudio Internacional sobre Sibilancias en Lactantes (EISL). The questionnaire was applied to parents of 9345 infants aged 12–15 months at the time of immunization/routine visits.

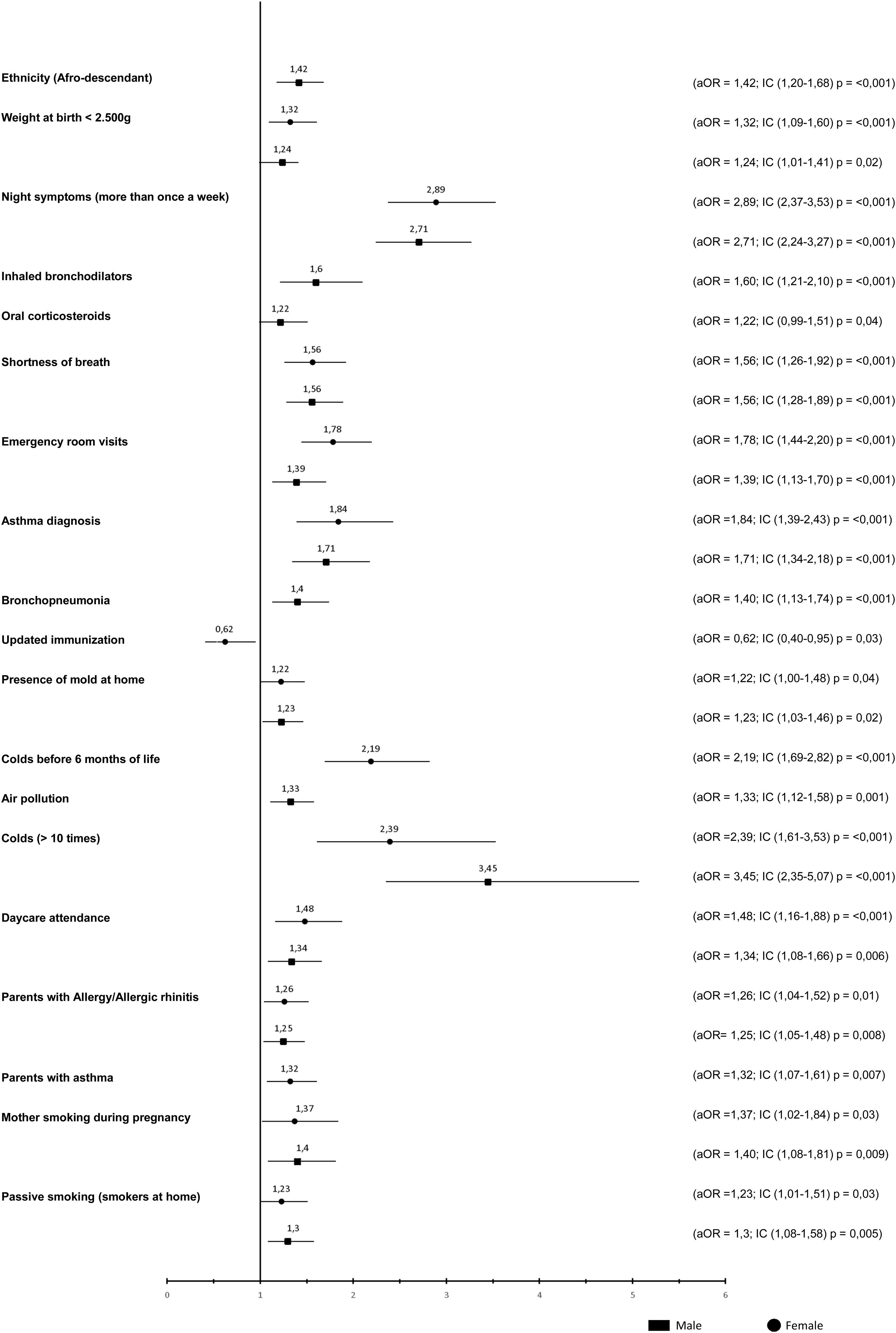

ResultsOne thousand two hundred and sixty-one (13.5%) males and nine hundred sixty-three (10.3%) females have had RW (≥3 episodes), respectively (p10 colds episodes (OR = 3.46; IC 95% 2.35–5.07), air pollution (OR = 1.33; IC 95% 1.12–1.59), molds at home (OR = 1.23; IC 95% 1.03–1.47), Afro-descendants (OR = 1.42; IC 95% 1.20–1.69), bronchopneumonia (OR = 1.41; IC; 1.11–1.78), severe episodes of wheezing in the first year (OR = 1.56; IC 95% 1.29–1.89), treatment with bronchodilators (OR = 1.60; IC 95% 1.22–2,1) and treatment with oral corticosteroids (OR = 1,23; IC 95% 0.99–1,52). Associated factors for RW for females were passive smoking (OR = 1.24; IC 95% 1.01−1,51), parents diagnosed with asthma (OR = 1.32; IC 95% 1,08−1,62), parents with allergic rhinitis (OR = 1.26; IC 95% 1.04–1.53), daycare attendance (OR = 1.48; IC 95% 1.17−1,88), colds in the first 6 months of life (OR = 2.19; IC 95% 1.69–2.82), personal diagnosis of asthma (OR = 1.84; IC 95% 1.39–2.44), emergency room visits (OR = 1.78; IC 95% 1.44–2.21), nighttime symptoms (OR = 2.89; IC 95% 2.34–3.53) and updated immunization (OR = 0.62; IC 95% 0.41−0.96).

ConclusionThere are differences in associated factors for RW between genders. Identification of these differences could be useful to the approach and management of RW between boys and girls.

The National and International Guidelines for management of asthma differ in the definition of recurrent wheezing in terms of the number of wheezing episodes, ranging from at least three to four episodes in the past year.1–5

Various phenotypes of wheezing have been described in epidemiological studies, but not all children wheezing will be asthmatic. The task force of the European Respiratory Society classifies wheezing phenotypes as follows: (1) episodic wheezing, which includes wheezing during a discrete period, wheezing associated with cold, and asymptomatic status during the inter-critical period or (2) wheezing due to multiple triggers, such as that in patients presenting recurrent wheezing episodes and symptoms including coughing and wheezing during the period between episodes, during sleep, and triggered by physical activity, laughter, or crying.1 According to some authors, reference to the expression “recurrent wheezing,” that is, more than three episodes of wheezing per year, has been used as a synonym for asthma.2,4

The EISL (from Spanish: Estudio Internacional Sobre Sibilancias en Lactantes; initials in Spanish meaning International Infant Wheezing Study) initiative arose from the need for knowledge regarding the epidemiology of wheezing in the first year of life. A standardized and validated questionnaire was applied to parents of infants aged between 12 and 15 months as previously reported.6–8

The EISL questionnaire was applied to 3003, 1014, 1261, 1013, and 1071 individuals in Curitiba, São Paulo, Belo Horizonte, Porto Alegre, and Recife, respectively. Approximately half of the infants had at least one episode of wheezing [Curitiba (45.4%), São Paulo (46%), Belo Horizonte (52%), Porto Alegre (61%), and Recife (43%)], and approximately one-fourth of them [Curitiba (22.6%), São Paulo (26.6%), Belo Horizonte (28.4%), Porto Alegre (36.3%), and Recife (25%)] had recurrent episodes of wheezing (three or more), with a mean onset at the age of 5 months.9–13

In a long-term cohort following 1246 newborns in Tucson, USA, the onset of recurrent wheezing and asthma was seen earlier in males than females.14 Among the factors associated with recurrent wheezing in infants, having asthmatic parents, history of bronchopneumonia, dogs at home, visits to daycare centers and maternal smoking during pregnancy were found to be the risk factors, whereas higher maternal education and the late onset of a cold were the protective factors.15

Despite knowledge regarding the higher prevalence in boys and associated factors in both sexes, boys and girls must have different factors associated with the development of recurrent wheezing at this stage in life and there is a need to characterize specific factors associated with recurrent wheezing that are inherent to each sex. The objective of this study was to identify the factors associated with recurrent wheezing in different sexes in the first year of life.

MethodIn this transversal, multicenter study, the standardized methodology of EISL was applied using Phase I database. Five centers from the cities of Belo Horizonte, Belém, Curitiba, Recife, and São Paulo participated in the study.

There was no difference in the period of application of the questionnaires to the parents/guardians of male or female infants.

The factors associated with occasional (<3 episodes) or recurrent wheezing (≥3 episodes) in the sexes were evaluated. The variables were divided into three groups: Block I) socio-demographic characteristics; Block II) occurrence of wheezing and infections; Block III) biological and environmental factors.

The statistical analysis was performed with EpiInfo 7.2.2 software (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, The United States of America). Categorical variables are presented as frequency and proportion distributions, and continuous variables as means and standard deviation. The Chi–square test was used for comparison of proportions, and the Student's t-test was used for comparison of the mean values.

The relationship between each explanatory variable and the dependent variable (wheezing and non-wheezing) for each sex was evaluated, and the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were calculated. For multivariate analysis, logistic regression was used, and variables with values of p < 0.20 were entered into the model.

The factors presented in blocks I, II and III in Tables 2 (boys) and 3 (girls), of bivariate analyzes, are those that had statistical significance (p < 0.05), and therefore are not the same. The variables that had no statistically significant result (p > 0.05) were suppressed to reduce the size of Tables 2 and 3, as the questionnaire is extensive.

The adjusted OR and 95% CI were calculated. Values of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. In another analysis, the process was repeated with substitution of the outcome of wheezing for the degree of recurrence (recurrent or occasional wheezing) of each sex.

The project was approved by the Complexo Hospital de Clínicas Human Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Paraná, and the parents and/or legal representatives of infants aged between 12 and 15 months signed the Informed Consent Term (TCLE).

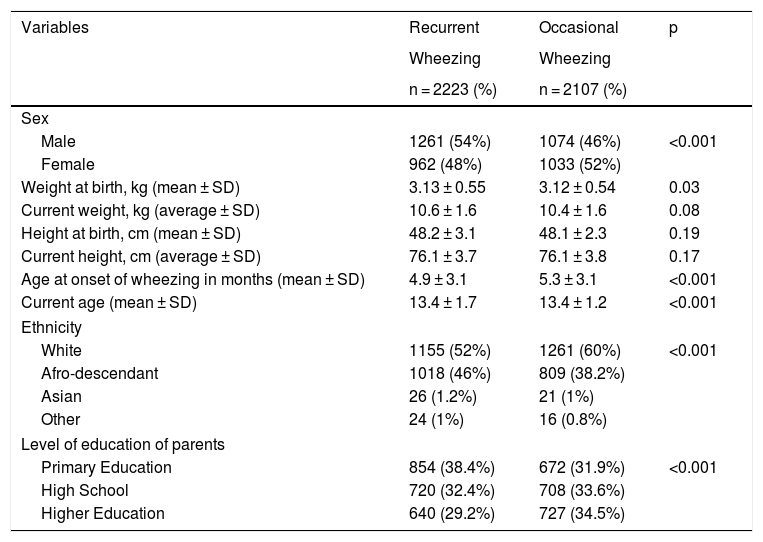

ResultsA total of 9349 infants were included in Belo Horizonte (n = 1231), Belém (n = 3024), Curitiba (n = 3004), São Paulo (n = 1013), and Recife (n = 1077). Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of infants with recurrent and occasional wheezing.

Demographic characteristics of infants with recurrent and occasional wheezing.

| Variables | Recurrent | Occasional | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wheezing | Wheezing | ||

| n = 2223 (%) | n = 2107 (%) | ||

| Sex | |||

| Male | 1261 (54%) | 1074 (46%) | <0.001 |

| Female | 962 (48%) | 1033 (52%) | |

| Weight at birth, kg (mean ± SD) | 3.13 ± 0.55 | 3.12 ± 0.54 | 0.03 |

| Current weight, kg (average ± SD) | 10.6 ± 1.6 | 10.4 ± 1.6 | 0.08 |

| Height at birth, cm (mean ± SD) | 48.2 ± 3.1 | 48.1 ± 2.3 | 0.19 |

| Current height, cm (average ± SD) | 76.1 ± 3.7 | 76.1 ± 3.8 | 0.17 |

| Age at onset of wheezing in months (mean ± SD) | 4.9 ± 3.1 | 5.3 ± 3.1 | <0.001 |

| Current age (mean ± SD) | 13.4 ± 1.7 | 13.4 ± 1.2 | <0.001 |

| Ethnicity | |||

| White | 1155 (52%) | 1261 (60%) | <0.001 |

| Afro-descendant | 1018 (46%) | 809 (38.2%) | |

| Asian | 26 (1.2%) | 21 (1%) | |

| Other | 24 (1%) | 16 (0.8%) | |

| Level of education of parents | |||

| Primary Education | 854 (38.4%) | 672 (31.9%) | <0.001 |

| High School | 720 (32.4%) | 708 (33.6%) | |

| Higher Education | 640 (29.2%) | 727 (34.5%) | |

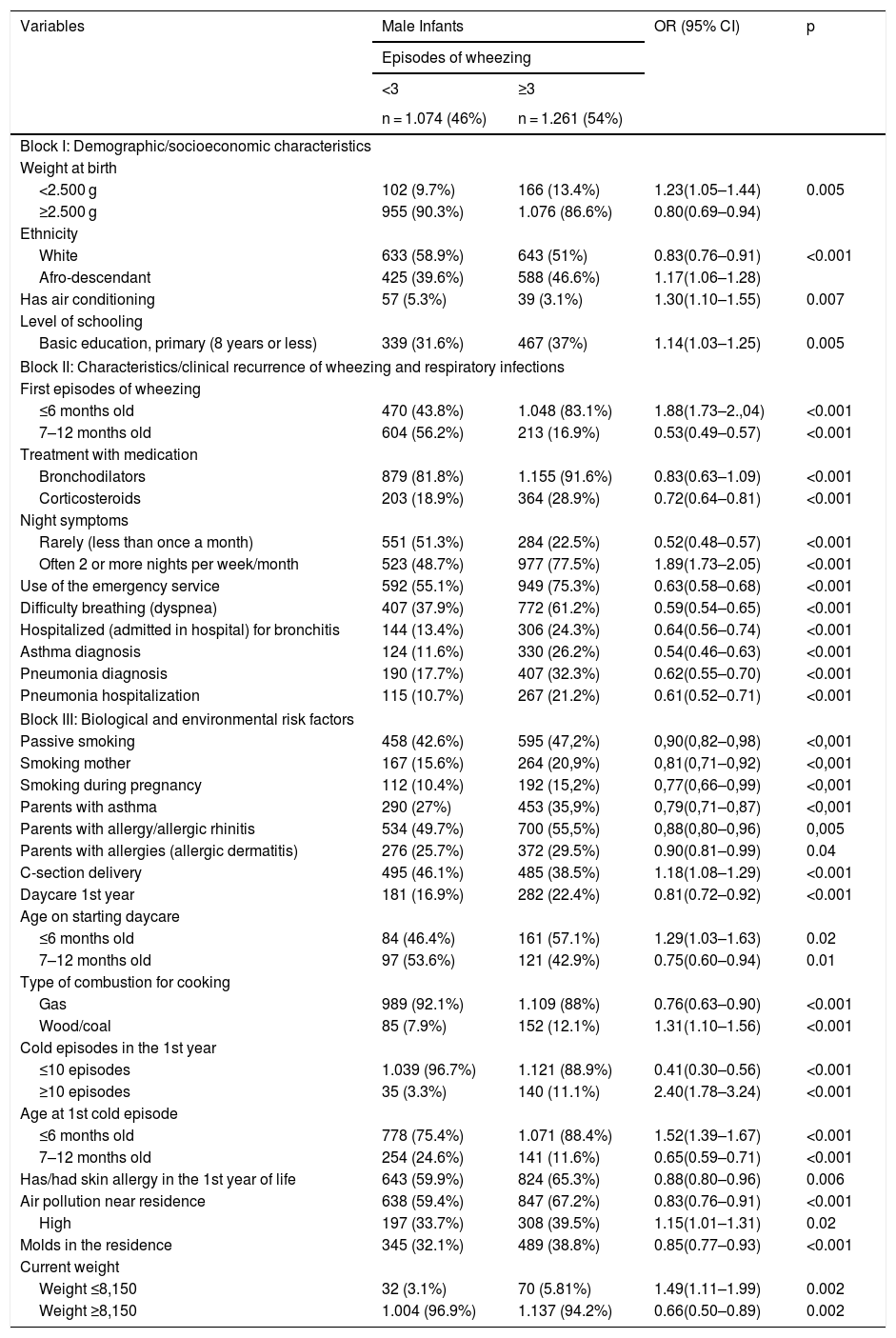

Factors associated with recurrent wheezing in boys after bivariate analysis (n = 2335).

| Variables | Male Infants | OR (95% CI) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Episodes of wheezing | ||||

| <3 | ≥3 | |||

| n = 1.074 (46%) | n = 1.261 (54%) | |||

| Block I: Demographic/socioeconomic characteristics | ||||

| Weight at birth | ||||

| <2.500 g | 102 (9.7%) | 166 (13.4%) | 1.23(1.05–1.44) | 0.005 |

| ≥2.500 g | 955 (90.3%) | 1.076 (86.6%) | 0.80(0.69–0.94) | |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White | 633 (58.9%) | 643 (51%) | 0.83(0.76–0.91) | <0.001 |

| Afro-descendant | 425 (39.6%) | 588 (46.6%) | 1.17(1.06–1.28) | |

| Has air conditioning | 57 (5.3%) | 39 (3.1%) | 1.30(1.10–1.55) | 0.007 |

| Level of schooling | ||||

| Basic education, primary (8 years or less) | 339 (31.6%) | 467 (37%) | 1.14(1.03–1.25) | 0.005 |

| Block II: Characteristics/clinical recurrence of wheezing and respiratory infections | ||||

| First episodes of wheezing | ||||

| ≤6 months old | 470 (43.8%) | 1.048 (83.1%) | 1.88(1.73–2.,04) | <0.001 |

| 7–12 months old | 604 (56.2%) | 213 (16.9%) | 0.53(0.49–0.57) | <0.001 |

| Treatment with medication | ||||

| Bronchodilators | 879 (81.8%) | 1.155 (91.6%) | 0.83(0.63–1.09) | <0.001 |

| Corticosteroids | 203 (18.9%) | 364 (28.9%) | 0.72(0.64–0.81) | <0.001 |

| Night symptoms | ||||

| Rarely (less than once a month) | 551 (51.3%) | 284 (22.5%) | 0.52(0.48–0.57) | <0.001 |

| Often 2 or more nights per week/month | 523 (48.7%) | 977 (77.5%) | 1.89(1.73–2.05) | <0.001 |

| Use of the emergency service | 592 (55.1%) | 949 (75.3%) | 0.63(0.58–0.68) | <0.001 |

| Difficulty breathing (dyspnea) | 407 (37.9%) | 772 (61.2%) | 0.59(0.54–0.65) | <0.001 |

| Hospitalized (admitted in hospital) for bronchitis | 144 (13.4%) | 306 (24.3%) | 0.64(0.56–0.74) | <0.001 |

| Asthma diagnosis | 124 (11.6%) | 330 (26.2%) | 0.54(0.46–0.63) | <0.001 |

| Pneumonia diagnosis | 190 (17.7%) | 407 (32.3%) | 0.62(0.55–0.70) | <0.001 |

| Pneumonia hospitalization | 115 (10.7%) | 267 (21.2%) | 0.61(0.52–0.71) | <0.001 |

| Block III: Biological and environmental risk factors | ||||

| Passive smoking | 458 (42.6%) | 595 (47,2%) | 0,90(0,82–0,98) | <0,001 |

| Smoking mother | 167 (15.6%) | 264 (20,9%) | 0,81(0,71–0,92) | <0,001 |

| Smoking during pregnancy | 112 (10.4%) | 192 (15,2%) | 0,77(0,66–0,99) | <0,001 |

| Parents with asthma | 290 (27%) | 453 (35,9%) | 0,79(0,71–0,87) | <0,001 |

| Parents with allergy/allergic rhinitis | 534 (49.7%) | 700 (55,5%) | 0,88(0,80–0,96) | 0,005 |

| Parents with allergies (allergic dermatitis) | 276 (25.7%) | 372 (29.5%) | 0.90(0.81–0.99) | 0.04 |

| C-section delivery | 495 (46.1%) | 485 (38.5%) | 1.18(1.08–1.29) | <0.001 |

| Daycare 1st year | 181 (16.9%) | 282 (22.4%) | 0.81(0.72–0.92) | <0.001 |

| Age on starting daycare | ||||

| ≤6 months old | 84 (46.4%) | 161 (57.1%) | 1.29(1.03–1.63) | 0.02 |

| 7–12 months old | 97 (53.6%) | 121 (42.9%) | 0.75(0.60–0.94) | 0.01 |

| Type of combustion for cooking | ||||

| Gas | 989 (92.1%) | 1.109 (88%) | 0.76(0.63–0.90) | <0.001 |

| Wood/coal | 85 (7.9%) | 152 (12.1%) | 1.31(1.10–1.56) | <0.001 |

| Cold episodes in the 1st year | ||||

| ≤10 episodes | 1.039 (96.7%) | 1.121 (88.9%) | 0.41(0.30–0.56) | <0.001 |

| ≥10 episodes | 35 (3.3%) | 140 (11.1%) | 2.40(1.78–3.24) | <0.001 |

| Age at 1st cold episode | ||||

| ≤6 months old | 778 (75.4%) | 1.071 (88.4%) | 1.52(1.39–1.67) | <0.001 |

| 7–12 months old | 254 (24.6%) | 141 (11.6%) | 0.65(0.59–0.71) | <0.001 |

| Has/had skin allergy in the 1st year of life | 643 (59.9%) | 824 (65.3%) | 0.88(0.80–0.96) | 0.006 |

| Air pollution near residence | 638 (59.4%) | 847 (67.2%) | 0.83(0.76–0.91) | <0.001 |

| High | 197 (33.7%) | 308 (39.5%) | 1.15(1.01–1.31) | 0.02 |

| Molds in the residence | 345 (32.1%) | 489 (38.8%) | 0.85(0.77–0.93) | <0.001 |

| Current weight | ||||

| Weight ≤8,150 | 32 (3.1%) | 70 (5.81%) | 1.49(1.11–1.99) | 0.002 |

| Weight ≥8,150 | 1.004 (96.9%) | 1.137 (94.2%) | 0.66(0.50–0.89) | 0.002 |

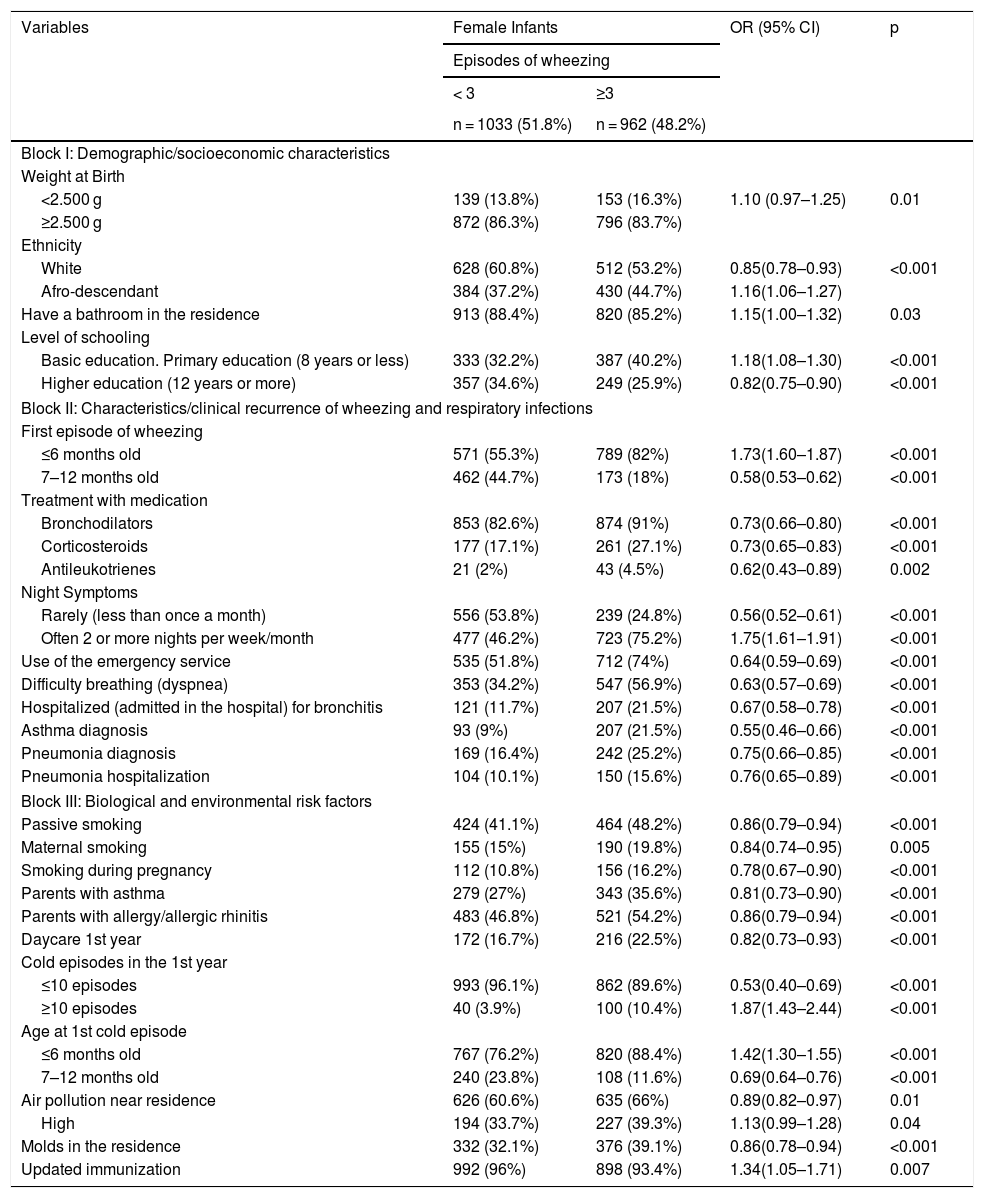

Factors associated with recurrent wheezing in girls after bivariate analysis (n = 1995).

| Variables | Female Infants | OR (95% CI) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Episodes of wheezing | ||||

| < 3 | ≥3 | |||

| n = 1033 (51.8%) | n = 962 (48.2%) | |||

| Block I: Demographic/socioeconomic characteristics | ||||

| Weight at Birth | ||||

| <2.500 g | 139 (13.8%) | 153 (16.3%) | 1.10 (0.97–1.25) | 0.01 |

| ≥2.500 g | 872 (86.3%) | 796 (83.7%) | ||

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White | 628 (60.8%) | 512 (53.2%) | 0.85(0.78–0.93) | <0.001 |

| Afro-descendant | 384 (37.2%) | 430 (44.7%) | 1.16(1.06–1.27) | |

| Have a bathroom in the residence | 913 (88.4%) | 820 (85.2%) | 1.15(1.00–1.32) | 0.03 |

| Level of schooling | ||||

| Basic education. Primary education (8 years or less) | 333 (32.2%) | 387 (40.2%) | 1.18(1.08–1.30) | <0.001 |

| Higher education (12 years or more) | 357 (34.6%) | 249 (25.9%) | 0.82(0.75–0.90) | <0.001 |

| Block II: Characteristics/clinical recurrence of wheezing and respiratory infections | ||||

| First episode of wheezing | ||||

| ≤6 months old | 571 (55.3%) | 789 (82%) | 1.73(1.60–1.87) | <0.001 |

| 7–12 months old | 462 (44.7%) | 173 (18%) | 0.58(0.53–0.62) | <0.001 |

| Treatment with medication | ||||

| Bronchodilators | 853 (82.6%) | 874 (91%) | 0.73(0.66–0.80) | <0.001 |

| Corticosteroids | 177 (17.1%) | 261 (27.1%) | 0.73(0.65–0.83) | <0.001 |

| Antileukotrienes | 21 (2%) | 43 (4.5%) | 0.62(0.43–0.89) | 0.002 |

| Night Symptoms | ||||

| Rarely (less than once a month) | 556 (53.8%) | 239 (24.8%) | 0.56(0.52–0.61) | <0.001 |

| Often 2 or more nights per week/month | 477 (46.2%) | 723 (75.2%) | 1.75(1.61–1.91) | <0.001 |

| Use of the emergency service | 535 (51.8%) | 712 (74%) | 0.64(0.59–0.69) | <0.001 |

| Difficulty breathing (dyspnea) | 353 (34.2%) | 547 (56.9%) | 0.63(0.57–0.69) | <0.001 |

| Hospitalized (admitted in the hospital) for bronchitis | 121 (11.7%) | 207 (21.5%) | 0.67(0.58–0.78) | <0.001 |

| Asthma diagnosis | 93 (9%) | 207 (21.5%) | 0.55(0.46–0.66) | <0.001 |

| Pneumonia diagnosis | 169 (16.4%) | 242 (25.2%) | 0.75(0.66–0.85) | <0.001 |

| Pneumonia hospitalization | 104 (10.1%) | 150 (15.6%) | 0.76(0.65–0.89) | <0.001 |

| Block III: Biological and environmental risk factors | ||||

| Passive smoking | 424 (41.1%) | 464 (48.2%) | 0.86(0.79–0.94) | <0.001 |

| Maternal smoking | 155 (15%) | 190 (19.8%) | 0.84(0.74–0.95) | 0.005 |

| Smoking during pregnancy | 112 (10.8%) | 156 (16.2%) | 0.78(0.67–0.90) | <0.001 |

| Parents with asthma | 279 (27%) | 343 (35.6%) | 0.81(0.73–0.90) | <0.001 |

| Parents with allergy/allergic rhinitis | 483 (46.8%) | 521 (54.2%) | 0.86(0.79–0.94) | <0.001 |

| Daycare 1st year | 172 (16.7%) | 216 (22.5%) | 0.82(0.73–0.93) | <0.001 |

| Cold episodes in the 1st year | ||||

| ≤10 episodes | 993 (96.1%) | 862 (89.6%) | 0.53(0.40–0.69) | <0.001 |

| ≥10 episodes | 40 (3.9%) | 100 (10.4%) | 1.87(1.43–2.44) | <0.001 |

| Age at 1st cold episode | ||||

| ≤6 months old | 767 (76.2%) | 820 (88.4%) | 1.42(1.30–1.55) | <0.001 |

| 7–12 months old | 240 (23.8%) | 108 (11.6%) | 0.69(0.64–0.76) | <0.001 |

| Air pollution near residence | 626 (60.6%) | 635 (66%) | 0.89(0.82–0.97) | 0.01 |

| High | 194 (33.7%) | 227 (39.3%) | 1.13(0.99–1.28) | 0.04 |

| Molds in the residence | 332 (32.1%) | 376 (39.1%) | 0.86(0.78–0.94) | <0.001 |

| Updated immunization | 992 (96%) | 898 (93.4%) | 1.34(1.05–1.71) | 0.007 |

Table 2 shows the associated factors with recurrent wheezing in a bivariate analysis in boys.

Table 3 shows the associated factors with recurrent wheezing in a bivariate analysis in girls.

The associated factors for RW for male were maternal smoking during pregnancy, >10 cold episodes, air pollution, molds at home, Afro-descendants, bronchopneumonia, severe episodes of wheezing in the first year, treatment with bronchodilators, treatment with oral corticosteroids. Associated factors for RW for females were passive smoking, parents diagnosed with asthma, parents with allergic rhinitis, daycare attendance, colds in the first 6 months of life, personal diagnosis of asthma, emergency room visits, nighttime symptoms and updated immunization.

Fig. 1 shows the associated factors for recurrent wheezing in boys and girls after a multivariate analysis.

DiscussionSeveral studies have shown differences in the prevalence of recurrent wheezing, ranging from 10% to 80.3% in the occurrence of wheezing at least once during the first 12 months of life, and 8%–43.1% of these infants were recurrent wheezers.16 The present study reported a 23.8% prevalence of recurrent wheezing with a male predominance. As previously reported, the prevalence of recurrent wheezing in early life is higher in boys. The reason is unknown, but boys and girls must have different factors associated with the development of recurrent wheezing at this stage of life.

The risk factors identified can be defined as environmental, socioeconomic, biological, and multifactorial.17 In the present study, low birth weight was associated with recurrent wheezing in both sexes, with a higher risk in girls than in boys.

Aranda et al.18 found in the EISL that the lower the birth weight, the greater the chance of wheezing, especially in girls, as they are born with less weight than boys. This can affect pulmonary development and reduce pulmonary respiratory function.

Asian ethnicity has been associated with protection and African descent has been considered as a risk factor for recurrent wheezing or asthma in children. A study that developed a score for predicting asthma in young children revealed that African-American children were twice as likely to develop asthma than children of other ethnic groups.19 In this study, Afro-descendant ethnicity was associated with recurrent wheezing in infants, but only in boys. However, no studies have found an association between recurrent wheezing limited to Afro-descendant boys; our findings may have been influenced by the fact that there was a predominance of Afro-descendant boys in this study.

Socioeconomic aspects are factors already identified for recurrent wheezing in infants of both sexes, such as the presence of an air conditioner unit, telephone set, carpet, bathroom and kitchen. The existence of lower socioeconomic conditions is predominant in the high associations of the prevalence of recurrent wheezing in infants, regardless of sex.3,11 For other authors who studied the prevalence of wheezing in children, the economic factor was independently associated with severity and the infants’ sex, with a significant association with male sex and poverty.7,10,20,21

According to Assis et al.17 and Medeiros et al.,13 the mother's education is a risk factor mainly for low schooling, while the higher education of infants’ mothers becomes a protective factor, although the degree of schooling may be related to the cultural and socioeconomic patterns of families.

The severity of recurrent wheezing, characterized by the presence of night symptoms, difficulty in breathing, and the use of emergency services did not differ between the sexes. The use of asthma medications was associated with recurrent wheezing in boys and the medical diagnosis of asthma was a risk factor for both sexes. Boys are at an increased risk of recurrent wheezing,8,12,13,17,22 and this relationship is reversed in adolescence. There is no evidence that wheezing is more serious in boys than in girls, and although it has been demonstrated that the diagnosis of asthma was similar among the sexes, the use of asthma medication at such an early age shows that we may face a contingent of individuals with asthma, especially among men.

The presence of mold in the household was a risk factor for recurrent wheezing among boys and girls. The mechanism by which children are exposed to intradomicile fungal antigens in their first year of life is unknown, but there is an increased risk of croup, pneumonia, bronchitis and bronchiolitis.23

The diagnosis of pneumonia was a risk factor for recurrent wheezing in boys, but not in girls. Furthermore, updated immunization was a protective factor only for girls. Bisgaard et al.24 observed in a cohort that episodes of wheezing in infants were associated with bacterial infections (OR = 2.9), regardless of viral infections. In this study, the lack of immunization in boys likely led to a higher number of respiratory infections of the lower tract (pneumonia) and, consequently, a higher number of episodes of wheezing in boys than in girls.

Air pollution was a risk factor for recurrent wheezing only in boys. Data published by the WHO show that air pollution has a wide and terrible impact on children's health and survival. Ambient and domestic air pollution contribute to respiratory tract infections; in 2016, 543,000 deaths of children under the age of 5 years were related to environmental risk factors.25 The airways of male infants are narrower than those of female infants; air pollution may be a risk factor for individuals with an anatomically disadvantaged respiratory tract with impaired lung function.26

Exposure to tobacco during pregnancy and at home after birth has been a risk factor in both sexes and has been well established in the pathophysiology of recurrent wheezing in infants.27

A family history of asthma was associated with the risk of recurrent wheezing in girls, while a family history of allergies or rhinitis was associated with the risk of recurrent wheezing in both sexes. The family history of asthma, especially from parents, has been reported as the most significant risk factor for recurrent wheezing in infants.12 In this study, the history of asthma in the parents of boys was not relevant; we suspect that for male infants, environmental factors are more responsible for recurrent wheezing than genetic factors.

The attendance of child care and the high number of cold episodes were associated with recurrent wheezing in both sexes of this population, but not the early onset of cold, which was a risk factor for girls. The frequency of day-care center visits and the high number of cold episodes, with early onset in life, can result in wheezing in infants.28 This is the first time that an early onset of viral respiratory infections (cold) is considered a risk factor for recurrent wheezing in female infants. Updated immunization of girls may reinforce that viral infectious agents are more significant than bacterial agents in these infants.

The use of a questionnaire to assess factors associated with a disease has been common in cross-sectional studies, however, this cause-and-effect relationship is limited, because it brings data from a moment's photography. The parents' response is also a limiting factor, as it is dependent on memory, and within 12 months of events, it can cause uncertainties in the responses. Another limitation is in the intensity classification variables, which are directly related to the understanding of each respondent, and their understanding may vary in the same population.

In conclusion, there are differences in the factors associated with recurrent wheezing in male and female infants. Further studies are needed to demonstrate the cause and effects of these factors to recurrent wheezing, where some of which are modifiable for each sex and can reduce the risk of recurrent wheezing at an early age.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.