To prospectively analyze the prognostic factors for neurological complications of childhood bacterial meningitis.

MethodsThis prospective study enrolled 77 children from 1 month until 16 years of age, treated for bacterial meningitis during the period of January 1, 2009 through December 31, 2010. 16 relevant predictors were chosen to analyze their association with the incidence of neurological complications. p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

ResultsOf the 77 children treated for bacterial meningitis, 33 patients developed neurological complications (43%), and two children died (2.6%). The etiology of bacterial meningitis cases was proven in 57/77 (74%) cases: 32 meningococci, eight pneumococci, six Gram-negative bacilli, five H. influenzae, five staphylococci, and one S. viridans isolates were found. Factors found to be associated with increased risk of development of neurological complications were age < 12 months, altered mental status, seizures prior to admission, initial therapy with two antibiotics, dexamethasone use, presence of focal neurological deficit on admission and increased proteins in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) (p < 0.05). Initial pleocytosis > 5,000 cells/mm3, pleocytosis > 5,000 cells/mm3 after 48hours, CSF/blood glucose ratio < 0.20, female gender, previous treatment with antibiotics, community-acquired infection, duration of illness > 48hours, presence of comorbidity, and primary focus of infection were not associated with increased risk for the development of neurological complications.

ConclusionAge < 12 months and severity of clinical presentation at admission were identified as the strongest predictors of neurological complications and may be of value in selecting patients for more intensive care and treatment.

Análise prospectiva de fatores de prognóstico para complicações neurológicas da meningite bacteriana infantil.

MétodosEste estudo prospectivo recrutou 77 crianças de um mês a 16 anos de idade tratadas de meningite bacteriana durante o período de 1/1/2009 a 31/12/2010. Foram escolhidos 16 preditores relevantes para analisar sua associação com a incidência de complicações neurológicas. Valores de p abaixo de 0,05 foram considerados estatisticamente significativos.

ResultadosDas 77 crianças tratadas para meningite bacteriana, desenvolveram-se complicações neurológicas em 33 pacientes (43%), e duas crianças morreram (2,6%). A etiologia dos casos de meningite bacteriana foi comprovada em 57/77 (74%) dos casos: foram encontrados 32 isolados de meningococos; 8 de pneumococos; 6 de bacilos gram-negativos; 5 de H. influenzae; 5 de estafilococos e 1 de S. viridans. Os fatores que se mostraram associados a aumento do risco de desenvolvimento de complicações neurológicas foram idade < 12 meses, alteração do estado mental, crises convulsivas antes da admissão, terapia inicial com dois antibióticos, uso de dexametasona, presença de déficit neurológico focal na admissão e aumento das proteínas do líquido cerebrospinal (LCS) (p<0,05). Pleiocitose inicial > 5.000 células/mm3, pleiocitose > 5.000 células/mm3 depois de 48 horas, baixa relação da glicose no LCS/sangue < 0,20, gênero feminino, tratamento prévio com antibióticos, infecção adquirida na comunidade, duração da doença > 48 horas, presença de comorbidade e foco primário de infecção não se associaram a aumento do risco para o desenvolvimento de complicações neurológicas.

ConclusãoIdade inferior a 12 meses e gravidade da apresentação clínica na admissão foram identificadas como os preditores mais fortes de complicações neurológicas e podem ter valor para selecionar pacientes para tratamento mais intensivo.

Despite the development of antibiotics that are more effective in treating bacterial meningitis, the mortality rates continue to be high, ranging between 5% and 30%, while as many as 50% of survivors experience neurological sequelae, such as hearing impairment, seizure disorders, and learning and behavioral problems.1–12 The neurological complications resulting from bacterial meningitis include subdural effusions or empyemas, cerebral abscesses, focal neurological deficits (e.g., hearing loss, cranial nerve palsies, hemiparesis, or quadriparesis), hydrocephalus, cerebrovascular abnormalities, altered mental status, and seizures. Acute bacterial meningitis is more common in resource-poor than resource-rich settings.3 The occurrence of negative consequences of bacterial meningitis in developed countries is strongly reduced by vaccination strategies, antibiotic treatment, and good care facilities.1,4,5 The speed of diagnosis, the identification of the causative pathogen, and the initial antimicrobial therapy represent important factors for the prognosis of bacterial meningitis in children. Developing countries such as Kosovo are still facing cases of bacterial meningitis in children due to non-implementation of vaccination programs against meningeal pathogens. Furthermore, the shortage of antibiotics in hospitals makes it difficult to follow guidelines for the initial empirical therapy of children with bacterial meningitis. Late and insufficient results of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) cultures and Gram-staining make treatment more difficult, particularly in cases with neurological complications.

From previous reports in Kosovo, the mortality rate of children with bacterial meningitis was 5.4%, while neurological complications were reported in 22% of cases.10 During the years of the present study, the annual incidence of bacterial meningitis was 3.0 cases per 100,000. Of the total bacterial meningitis cases (n=126), 77 (63%) were children up to 16 years of age, while 74% of pediatric bacterial meningitis cases occurred in children under 6 years of age.

The aim of this study was to perform a prospective multivariate analysis of statistically significant predictors for neurological complications of childhood bacterial meningitis.

Material and methodsChildren aged between 1 month and 16 years, treated for bacterial meningitis at the Infectious Diseases Clinic in Prishtina (University Clinical Center of Kosovo) during the period from January 1, 2009 to December 31, 2010 were prospectively enrolled in the study. The furthest distance from Prishtina is estimated to be < 100km or 1.5 hour driving. 57 children had a confirmed bacterial etiology. 20 patients were treated for probable bacterial meningitis, based on World Health Organization (WHO) criteria: clinical signs and symptoms of meningitis, changes in CSF, and lack of an identifiable bacterial pathogen. Children who didn’t fulfill the criteria for bacterial meningitis were excluded from the study. Cases of tuberculous meningitis and neurobrucellosis, as well as patients younger than 1 month old were excluded from the study. The following procedure was performed on admission for every child with suspected bacterial meningitis: lumbar puncture, fluid analysis (cell count with differential, glucose, protein), Gram-staining, and bacterial culture, repeated LPs after 48hours. The treatment was followed by laboratory analysis; evaluation by a neurologist, an ophthalmologist, and an ear, nose, and throat (ENT) specialist; and brain imaging when indicated. The diagnosis of neurologic complications was made by neurologic examination, neuroimaging, electroencephalography, and by the evaluation of a neurologist, ophthalmologist, ENT specialist, and psychologist. Indications for performing a computed tomography (CT) of the head after meningitis were: prolonged fever, focal neurological deficit, convulsions, worsening consciousness level, prolonged cyto-biochemical changes in CSF, or worsening of clinical presentation. The physicians of the ward for treatment of meningitis, including the first author, treated these children and performed a one-year follow up, which included routine visits to the clinic and consultations by phone. The initial antibiotic therapy was selected based on the clinical presentation of illness with prognostic factors for an unfavorable outcome (altered mental state, seizures, and neurologic deficit); the possible pathogen for each age group and the local antibiotic resistance patterns; duration of illness prior to admission; previous treatment with antibiotics; the presence of a primary infectious focus; the identification of a community- or hospital-acquired infection (shunt intervention, neurosurgery, etc.); presentation of petechial skin rash; underlying diseases; antibiotics available in the ward; and the financial resources of the parents.

Initial single-agent antibiotic therapy was used in 42 children (55%), mainly ceftriaxone (36/77, 47%), while 35 children (45%) were treated with initial dual-agent antibiotic therapy, mostly the combination of ceftriaxone with vancomycin (18/77, 23%). Dexamethasone was used in 66 children (86%), and criteria for its use were clinical presentation on admission, altered mental status, presence of seizures, or focal neurological deficit on admission.

In order to determine their association with the incidence of neurological complications of bacterial meningitis in children treated in this ward, 16 potentially relevant predictors were chosen to be analyzed. p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. There were no missing data on the 16 variables collected from the medical records including: 1) age (which was later categorized into specific age groups); 2) gender; 3) duration of the patients’ illness prior to admission, < or > 48hours; 4) previous treatment with antibiotics; 5) presence of altered mental status at the time of presentation; 6) presence of focal neurological deficits that occurred in the period between the start of symptoms and arrival at the admission room (cranial nerve involvement or hemiparesis/quadriparesis); 7) occurrence of seizures prior to admission; 8) initial single- or dual-agent antibiotic therapy; 9) use of dexamethasone; 10) presence/absence of a primary infectious focus; 11) presence/absence of comorbidity; 12) initial turbid CSF with pleocytosis > 5,000 cells/mm3; 13) pleocytosis > 5,000 cells/mm3 after 48 hoursl 14) CSF/blood glucose ratio < 0.20; 15) increased proteinorrhachia (> 0.50g/L); and 16) whether the infection was community- or hospital-acquired. Good outcome was considered treatment without any obvious neurological complications at discharge, and adverse outcome was considered the manifestation of neurological complications during the course of illness, or death. There were only two death cases who manifested neurological complications (obstructive hydrocephalus and cerebral abscesses), thus both were included in the group of children with neurological complications. All children were followed-up for a minimum of 12 months.

This study was approved by the Ethic-Professional Committee of the University Clinical Center of Kosova.

Statistical analysisData were analyzed using Stata 7.1 and the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) 13. The statistical parameters analyzed included structure index, mean, and standard deviation. p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

ResultsDuring the two-year study period, 77 children aged between 1 month and 16 years (57 children < 6 years; 48/77 males) were treated for bacterial meningitis. 57 children had a confirmed bacterial etiology, as follows: 32, Neisseria meningitidis; eight, Streptococcus pneumoniae; six, Gram-negative bacilli (three P. aeruginosa, two E. coli, and one K. pneumonia); five, Haemophilus influenzae type b; five, Staphylococcus aureus; and one, S. viridans. 20 patients were treated for probable bacterial meningitis, based upon the criteria mentioned in the Material and Methods section.

Of the 77 children treated for bacterial meningitis, 33 developed neurological complications (43%), and two children who presented with > 48hours of illness died (14-month-old child due to S. pneumoniae and 1-month-old child due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa).

The neurological complications observed were: subdural effusion (22/77; 28.6%); recurrent seizures (6/77; 7.8%); hemiparesis (5/77; 6.5%); intracerebral hemorrhage (3/77; 3.9%); cerebritis (3/77; 3.9%); facial nerve palsy (3/77; 3.9%); hydrocephalus (2/77; 2.6%); and single cases of subdural hematoma, cerebral abscess, subdural empyema, and purulent ventriculitis (1.3%).

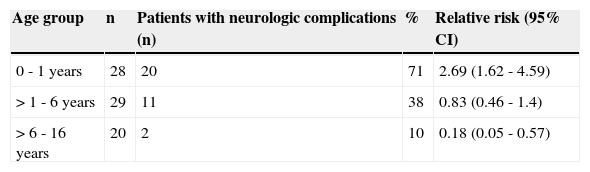

The highest incidence of neurological complications was observed in children < 12 months of age (p<0.05) (Table 1).

Relative risk for neurologic complications by age group during years 2009-2010.

| Age group | n | Patients with neurologic complications (n) | % | Relative risk (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 - 1 years | 28 | 20 | 71 | 2.69 (1.62 - 4.59) |

| > 1 - 6 years | 29 | 11 | 38 | 0.83 (0.46 - 1.4) |

| > 6 - 16 years | 20 | 2 | 10 | 0.18 (0.05 - 0.57) |

CI, confidence interval.

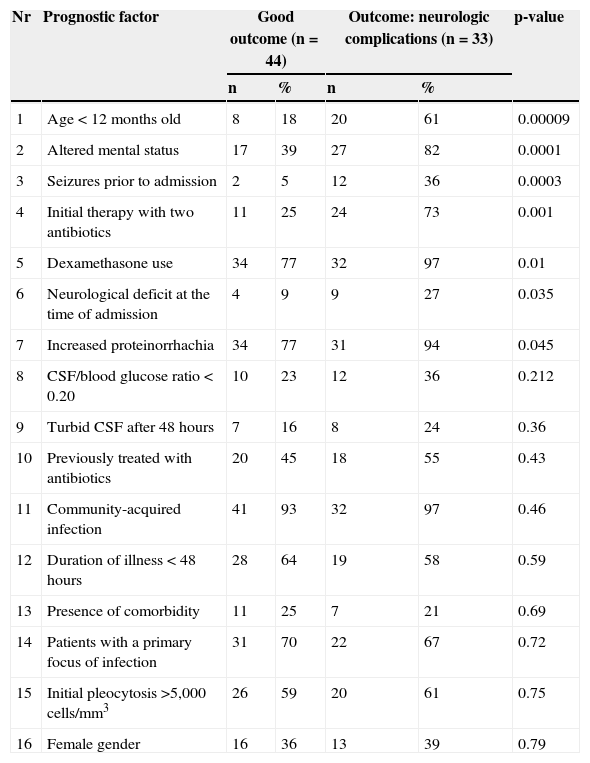

A total of 47 patients (61%) were admitted with duration of illness < 48hours. The mean duration of illness was 2.2 days, and there were no statistically significant differences in duration of illness according to age groups (p>0.05). A lower incidence of neurological complications was observed in children with duration of illness < 48hours (19 patients [40%]), as compared to patients who were admitted after two days of illness. The observed differences were not statistically significant (p > 0.05) (Table 2).

Association between various clinical factors and the development of neurological complications in children with bacterial meningitis.

| Nr | Prognostic factor | Good outcome (n=44) | Outcome: neurologic complications (n=33) | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |||

| 1 | Age < 12 months old | 8 | 18 | 20 | 61 | 0.00009 |

| 2 | Altered mental status | 17 | 39 | 27 | 82 | 0.0001 |

| 3 | Seizures prior to admission | 2 | 5 | 12 | 36 | 0.0003 |

| 4 | Initial therapy with two antibiotics | 11 | 25 | 24 | 73 | 0.001 |

| 5 | Dexamethasone use | 34 | 77 | 32 | 97 | 0.01 |

| 6 | Neurological deficit at the time of admission | 4 | 9 | 9 | 27 | 0.035 |

| 7 | Increased proteinorrhachia | 34 | 77 | 31 | 94 | 0.045 |

| 8 | CSF/blood glucose ratio < 0.20 | 10 | 23 | 12 | 36 | 0.212 |

| 9 | Turbid CSF after 48 hours | 7 | 16 | 8 | 24 | 0.36 |

| 10 | Previously treated with antibiotics | 20 | 45 | 18 | 55 | 0.43 |

| 11 | Community-acquired infection | 41 | 93 | 32 | 97 | 0.46 |

| 12 | Duration of illness < 48 hours | 28 | 64 | 19 | 58 | 0.59 |

| 13 | Presence of comorbidity | 11 | 25 | 7 | 21 | 0.69 |

| 14 | Patients with a primary focus of infection | 31 | 70 | 22 | 67 | 0.72 |

| 15 | Initial pleocytosis >5,000 cells/mm3 | 26 | 59 | 20 | 61 | 0.75 |

| 16 | Female gender | 16 | 36 | 13 | 39 | 0.79 |

CSF, cerebrospinal fluid.

Children who had seizures prior to admission (n=14, 18%) and those who were admitted with an altered mental status (n=44, 57%) were found to have higher incidence of neurological complications (p<0.05). There were no statistically significant differences in presentation of seizures, presence of neurological deficit, or alteration of mental status according to age group.

In addition, children who had focal neurological deficits at the time of admission (n=13, 17%) were found to be at increased risk for developing neurological complications (p<0.05).

The incidence of neurological complications was higher in patients treated with dexamethasone, compared to those who were not (p<0.05). The mean duration of illness before dexamethasone use was three days. Almost half of the patients (33 children, 49%) were previously treated with antibiotics, but they were not associated with increased incidence of neurological complications (p>0.05).

The incidence of neurological complications was higher in patients who, during the initial antibiotic treatment, were treated with two antibiotics (n=35; 45%), compared to those treated with one antibiotic (n=42; 55%) (p<0.05).

Increased protein levels (mean 1.63g/L) were found in 65 patients (84%), who also had higher incidence of neurological complications (p<0.05).

Initial turbid CSF with pleocytosis > 5,000 cells/mm3 (n=46; 60%) and turbid CSF with pleocytosis > 5,000 cells/mm3 after 48hours (n=15; 19%) were not associated with increased risk for developing neurological complications (p>0.05).

Patients who had, at the initial lumbar puncture, a CSF/blood glucose ratio < 0.20 were not at increased risk for developing neurological complications (p > 0.05).

The presence of a primary infectious focus (n=53; 69%), the presence of comorbidity (n=18; 23%), community-acquired infection (n=73; 95%), and female gender (n=29; 38%) were not associated with increased incidence of neurological complications (p>0.05).

The etiology of bacterial meningitis cases was proven in 57/77 cases (74%): 32 meningococci, eight pneumococci, six Gram-negative bacilli, five H. influenzae type B, five staphylococci, and one S. viridans isolates were found. Neurological complications developed more frequently in patients who were infected with S. pneumoniae (6/8), S. aureus (3/5), Gram-negative bacilli (2/6), N. meningitidis (8/32), and H. influenzae (1/5).

Children with bacterial meningitis were equally from rural (n=39) and urban places (n=38). A higher incidence of neurological complications was recorded in children from urban places (18/38; 47%) compared to children from rural places (15/39; 38%). None of the children attended kindergarten.

DiscussionDespite the progress in medicine, bacterial meningitis causes substantial morbidity and mortality in children in both developed1,2,9,11–16 and developing countries.6,10,17–20 Sensorineural hearing loss, seizures, motor problems, hydrocephalus and mental retardation, as well as more subtle outcomes like cognitive, academic, and behavioral problems are observed in post-meningitis children.7,9,12,13 Chandran A. et al., in their systematic literature search, found that 49% of survivors of childhood bacterial meningitis were reported to have one or more long-term sequelae. The majority of reported sequelae were behavioral and/or intellectual disorders (45%).21 The risk of long term sequelae is higher in individuals who have acute neurological complications during the course of the disease.6,8 Identification of predictors for early neurological complications is extremely important, since they are also the first predictors of long-term sequelae of childhood bacterial meningitis.

Several studies of clinical features and prognostic factors in children with bacterial meningitis have been performed,2,6–8,11–14,17,22,23 and the majority were conducted in developed countries. In the present study, the influence of 16 potentially important prognostic factors for neurological complications in children with bacterial meningitis were prospectively analyzed in a developing country. Young age (indicated as younger than two years old), is considered an important prognostic factor for adverse outcome of children with bacterial meningitis.2,18 In this study, age < 12 months was also identified as predictor for neurological complications. From a previous report by the authors, age < 12 months was a risk factor for both early neurological complications and long-term sequelae of bacterial meningitis in children.24

Severity of clinical presentation, manifested by the alteration of mental status and the occurrence of seizures, are identified as the strongest prognostic factors for neurological complications in the present study, similar to that indicated in numerous studies from developed12,14,16,25,26 and developing countries.6,17–20,27,28 Klinger et al. found that duration of seizures for > 72hours and presence of coma were the most important predictors of adverse outcome.25

Time required for establishing a diagnosis of bacterial meningitis depends on the ability of primary health care services to accurately assess the symptoms and to order immediate patient transfer to specialized institutions in which the prompt diagnosis can be confirmed and a suitable antimicrobial therapy can be initiated. Delay in treatment is associated with an increased risk of neurological disability and death in both developed13,22,25 and developing countries.10,17,19,28 In the present study, duration of illness > 48hours was associated with increased incidence of neurological complications in survivors compared to children with duration of illness < 48hours, but the differences were not statistically significant. The mean duration of illness prior to admission was 2.2 days, which the authors consider to be an improvement of their health care system and socioeconomic conditions compared to previous reports, where the mean duration of illness in children with bacterial meningitis was 3.7 days.10 Two other benefit factors are existence of the specialized ward for treatment of CNS infections in children at the Infectious Diseases Clinic in Prishtina (the capital city of Kosovo) for more than 36 years, and that the furthest distance from Prishtina is estimated to be < 100km or 1.5hours of driving.

A decade after the war in Kosovo (1999), many private clinics opened, with no control of which first-line antibiotics were given to children. Most pediatricians and family doctors prescribe third generation cephalosporins, especially ceftriaxone, as a first-line antibiotic therapy for febrile illness in children. Almost half of the patients (49%) were previously treated with antibiotics, but they were not associated with an increased incidence of neurological complications. In the authors’ prior study, previous treatment with antibiotics was found to be associated with increased risk for death.10

Children who manifested focal neurological deficit at admission had a significantly higher incidence of neurological complications. Oostenbrik et al. found that children with acute focal neurological symptoms tend to have the worst prognosis.12

The incidence of neurological complications was significantly higher in patients who were initially treated with two antibiotics (n=35; 45%), as those children presented severe clinical presentation at admission. The most administered initial antibiotic therapy was the combination of ceftriaxone with vancomycin (23%).

Many clinical trials were undertaken to determine the effects of adjunctive dexamethasone on the outcome in children with bacterial meningitis.10,16,22,29 The results, however, do not point unequivocally to a beneficial effect.29,30 In this study, adjunctive dexamethasone therapy did not reduce the incidence of neurological complications in children with bacterial meningitis. The beneficial effect of dexamethasone use could not be proved, as a result of several factors: dexamethasone was used in patients who presented with the severe clinical form of illness at admission, the mean duration of illness prior to dexamethasone use was three days, and half of children were previously treated with antibiotics.

Other risk factors identified by previous studies include alterations in various CSF parameters. Low CSF leukocyte count, low CSF glucose level, low CSF/blood glucose level, and high CSF protein level have been identified as significant factors predicting neurological complications of bacterial meningitis in children in both developed9,11,13–16,26 and developing countries.17–20,28

In this study, only increased CSF protein level was identified as risk factor for neurological complications. Initial turbid CSF with pleocytosis > 5,000 cells/mm3, turbid CSF after 48hours, and CSF/blood glucose ratio < 0.20 were not identified as statistically significant factors for the development of neurological complications.

An association between meningitis caused by S. pneumoniae and unfavorable evolution has been suggested in the literature.11–13,16,17,19 According to Antoniuk et al., infection with S. pneumoniae is considered a risk factor for acute neurological complication.6 In the present study, neurological complications developed more frequently in patients who were infected with S. pneumoniae.

Presence of a primary focus of infection, presence of comorbidity, community-acquired infection, and female gender were not found to be associated with increased risk for the development of neurological complications.

The primary meningeal pathogen involved in causing community-acquired bacterial meningitis in children from Kosovo continues to be N. meningitidis. Hib vaccination during routine childhood immunization in Kosovo has been implemented only since 2010, giving hope to reduce the burden of bacterial meningitis in children. The implementation of protocols for the empirical treatment of bacterial meningitis to reduce the mortality rate and the incidence of neurological complications is the goal of future treatments of children.

In conclusion, age < 12 months and severity of clinical presentation at admission (alteration of mental status and the occurrence of seizures) were identified as the strongest predictors for neurological complications, and may be of value in selecting patients for more intensive care and treatment.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The authors would like to thank the personnel of Infectious Diseases Clinic of Prishtina for their support during this study.

Please cite this article as: Namani S, Milenković Z, Koci B. A prospective study of risk factors for neurological complications in childhood bacterial meningitis. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2013;89:256–62.