The study aimed to determine the practices used by breastfeeding mothers to wean their children from the breast.

MethodThis qualitative–quantitative research was conducted with mothers whose children were registered the pediatric clinics of a state hospital between June and September 2016. In accordance with a purposeful sampling method, 232 mothers of children between the ages of 2 and 5 years were included in the study. Data were collected through face-to-face interviews using a questionnaire with demographic characteristics of mothers as well as their weaning practices. The data obtained were analyzed with a computer-assisted program using number and percentage distributions.

ResultsThe mean breastfeeding duration was 19.00±7.11 months. It was determined that the majority of mothers (56.5%) used traditional methods for weaning their children. These included applying substances with a bad taste (58.1%) to their breasts, covering their breasts with various materials (26.2%) to make the child not want to nurse anymore, and using a pacifier or feeding bottle (9.2%) to substitute for the mother's breast.

ConclusionsIt was observed that more than half of the mothers were used some traditional practices that could cause trauma in their children, instead of natural weaning.

O estudo visou determinar as práticas utilizadas por mães em amamentação para desmamar seus filhos do peito.

MétodoEssa pesquisa qualitativa-quantitativa foi realizada com mães cujos filhos foram registrados em clínicas pediátricas de um hospital estadual entre junho-setembro de 2016. De acordo com o método de amostragem proposital, 232 mães de crianças com idades entre 2 e 5 anos foram incluídas no estudo. Os dados foram coletados por meio de entrevistas presenciais que utilizam um questionário com características demográficas das mães, bem como suas práticas de desmame. Os dados obtidos foram analisados com um programa de computador que utiliza distribuições numéricas e percentuais.

ResultadosA duração média de amamentação foi de 19±7,11 meses. Foi determinado que a maior parte das mães (56,5%) utilizou métodos tradicionais para desmamar seus filhos. Esses métodos incluíram aplicar substâncias com gosto ruim (58,1%) em seus seios, cobrir seus seios com materiais diversos (26,2%) para fazer com que seu filho deixe de querer mamar e utilizar chupeta ou mamadeira (9,2%) para substituir o peito da mãe.

ConclusõesFoi observado que mais da metade das mães estavam utilizando algumas práticas tradicionais que podem causar trauma em seus filhos, em vez do desmame natural.

Mother's milk is an essential nutrient that meets the basic nutritional needs of the baby.1,2 As a cultural phenomenon with social and spiritual dimensions, breastfeeding supports psychosocial development through the mother–infant bond, while meeting the physiological requirements of the baby.3,4 For these reasons, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends breastfeeding for two years or longer, using only breastmilk for the first six months after birth and thereafter with additional nutrients.5 However, 49% of infants born in 2011 were breastfeed at the age of 6 months and 27% at 12 months.6 The mean duration of breastfeeding is longer in countries with low levels of income than in those with higher levels of income.7

Many factors affect the breastfeeding behaviors of mothers. Studies show the presence of a relationship between weaning and factors such as age of the mother,8,9 employment status, breastfeeding problems,8,10 mother's health problems,11 place of residence, and socioeconomic status,12 pregnancy,8 early food introduction, and the inability to get support for breastfeeding.2,9,13 A review of the practices of mothers and the weaning process indicates that this topic has not been adequately studied. Moreover, few studies have reported the use of traditional weaning practices.14,15 Traditional practices aim to terminate breastfeeding quickly. However, a review of the literature showed that the benefits and disadvantages of traditional weaning practices have not been well researched. It is known that abrupt and sudden termination of breastfeeding, which is an important link between mother and baby, and the methods used for this purpose may cause trauma to both the mother and baby.2,14 It may negatively affect the infant's mental–social development as well as the bonding between mother and child; it may also increase the risk of neglect and abuse. Additional risks include the baby's refusal of food, dehydration, and malnutrition.14

The success of the breastfeeding process depends on whether or not the mothers receive adequate information and support regarding the development of their child. In line with this, there are opportunities for nurses, who work with mothers and children, to offer counseling and education to nursing mothers in support of this goal. The specific roles of health professionals should be implemented during the initiation phase of breastfeeding, its continuation, and during the weaning phase. Health professionals understand the importance of encouraging mothers, when possible, to breastfeed for two years; they can also provide instruction on the practices that support a healthy mother–infant separation during the weaning process. At this time, mothers would have the opportunity to learn about the benefits and disadvantages of the various practices.

Purpose of the studyThe aim of this study was to evaluate the weaning practices of mothers of children aged 2–5 years who terminated breastfeeding at any time.

MethodsStudy designIn this study, a qualitative–quantitative method was used. For this purpose, Creswell's concurrent transformative mixed-model research design was adopted.16 In this design, which helps to better understand the facts and alternative approaches, qualitative and quantitative data were collected concurrently and analyzed together to provide strong evidence for the results.

SampleThe sample of the study consisted of mothers of children aged 2–5 years admitted to the pediatric clinic of a state hospital. A purposeful sampling method was used to select 232 mothers.17 Mothers with breastfeeding experience of any duration were included in the study. Sample size was calculated before data collecting process, considering an alpha at 0.05 as significant level, the incidence of population was taken 0.50 and incidence of study group was taken 0.40 and statistical power was taken 0.85. Sample size was determined to be 221 mothers. However, to account for possible losses during analysis, 5% more mothers were included in the study.

Data collectionBased on the current available literature,1,2,8,18 a questionnaire was developed by the researchers, and the study data were collected between June and September 2016. The questionnaire consisted of 20 items to assess mothers’ weaning practices, as well as their descriptive characteristics. An in-depth effort was made to understand mothers’ rationale as well as the methods used to wean their children. For this study, quantitative and qualitative data were collected simultaneously, and each interview lasted approximately 20–25min. Data were collected in face-to-face interviews. Two basic questions were asked to better understand the breastfeeding practices of mothers: “How did you decide to wean your child?” “Which methods did you use for weaning?”

The quantitative data obtained were transferred to SPSS (SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 18.0, Chicago, USA). The data were analyzed using percentiles and averages. Furthermore, mothers’ rationale for termination of breastfeeding was categorized using content analysis. Data were categorized according to the literature and were then converted into quantitative data. Each category was supported with qualitative statements.

Ethical dimensionsBefore collecting the study data, approval of the ethics committee was obtained from the Fırat University Non-Interventional Research Ethics Committee. Written permission from the studied institution and verbal consent of mothers were obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

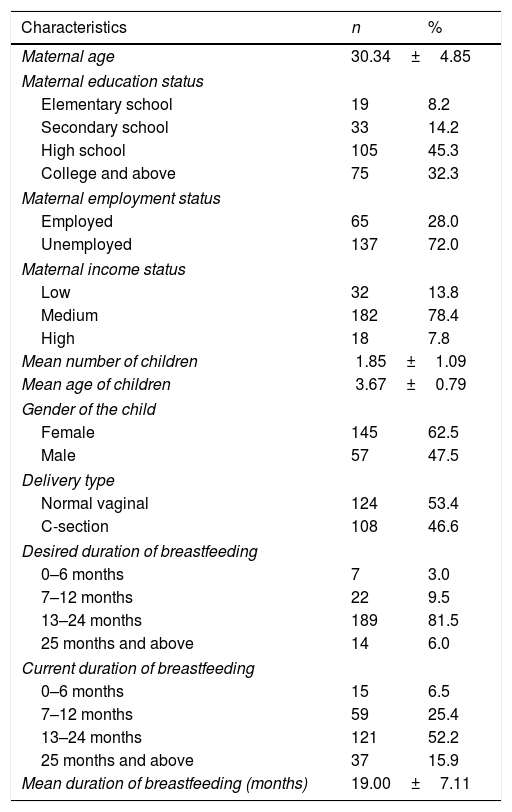

ResultsThe demographic characteristics of the mothers and their children were shown in Table 1. Most of the mothers (81.5%) had hoped to breastfeed for 13–24 months; however, only 52.2% were able to do so.

Demographic characteristics of the mothers and children.

| Characteristics | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Maternal age | 30.34±4.85 | |

| Maternal education status | ||

| Elementary school | 19 | 8.2 |

| Secondary school | 33 | 14.2 |

| High school | 105 | 45.3 |

| College and above | 75 | 32.3 |

| Maternal employment status | ||

| Employed | 65 | 28.0 |

| Unemployed | 137 | 72.0 |

| Maternal income status | ||

| Low | 32 | 13.8 |

| Medium | 182 | 78.4 |

| High | 18 | 7.8 |

| Mean number of children | 1.85±1.09 | |

| Mean age of children | 3.67±0.79 | |

| Gender of the child | ||

| Female | 145 | 62.5 |

| Male | 57 | 47.5 |

| Delivery type | ||

| Normal vaginal | 124 | 53.4 |

| C-section | 108 | 46.6 |

| Desired duration of breastfeeding | ||

| 0–6 months | 7 | 3.0 |

| 7–12 months | 22 | 9.5 |

| 13–24 months | 189 | 81.5 |

| 25 months and above | 14 | 6.0 |

| Current duration of breastfeeding | ||

| 0–6 months | 15 | 6.5 |

| 7–12 months | 59 | 25.4 |

| 13–24 months | 121 | 52.2 |

| 25 months and above | 37 | 15.9 |

| Mean duration of breastfeeding (months) | 19.00±7.11 | |

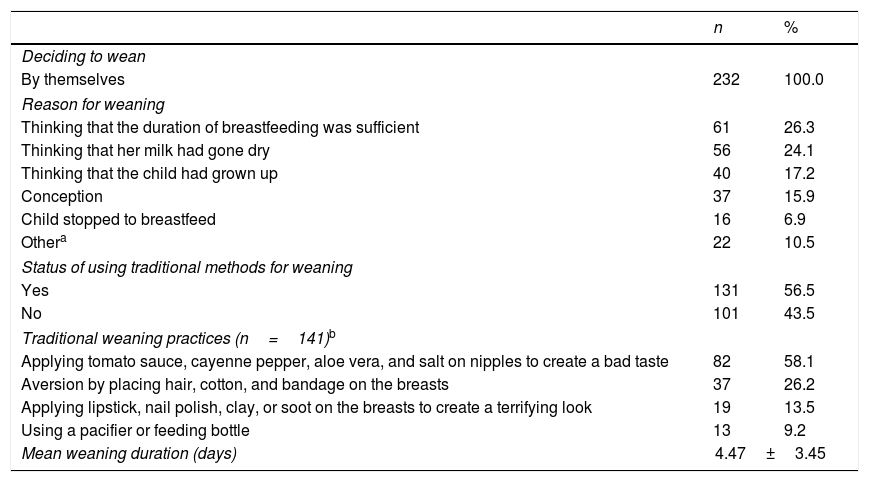

Within the scope of the study, the rationale of mothers for weaning their children was assessed. The results showed that 26.3% of the mothers stated that their child had breastfed for an adequate period of time, 24.1% thought that their milk had dried up, 17.2% thought that the child was old enough to be weaned, and 15.9% had terminated breastfeeding because they were pregnant. “My child had grown much. She had teeth, and was biting. I was in pain while breastfeeding. I felt she was using the breasts just to be playful, so I decided to wean.” “I learned I was pregnant... Breastfeeding was not recommended during pregnancy. I had to stop breastfeeding when she was 13 months old.” “I decided to wean by myself. She was 20 months old, and was able to eat everything. Breastfeeding would not help the child...”

Based on the goals of the study, the rationale of mothers for weaning was assessed and categorized. According to the findings, most of the mothers (56.5%) had tried one of the traditional methods (presented below) to interrupt breastfeeding.

More than one-third (58.1%) applied tomato sauce, cayenne pepper, aloe vera, and salt on their nipples to create a bad taste for the nursing child. “I applied cayenne pepper to the nipple before breastfeeding. My child cried due to the bitter taste of my breasts, and moved away. My child would ask to breastfeed from time to time, but would gave up after saying ‘It's bitter’.”

Some of the mothers (13.5%) applied lipstick, nail polish, clay, or soot on the breasts to create a fear-inducing sight to discourage the child from nursing anymore. “I applied lipstick on my nipples, and ‘look it's bleeding’ I said. The expression of her face changed and started to cry... and my child avoided my breasts since then.”

A small percentage of mothers (26.2%) attempted to create an aversion to breastfeeding by placing hair, cotton, and bandages on the breasts. This method also made it difficult for their children to access the breasts. “I cut my hair and glued it onto my breasts. I showed it to my child, and said ‘breast is dirty.’ My child asked to breastfeed persistently. ‘You can suck on the nipple,’ I said. I put the nipple in her mouth, and the hair on top of breasts prevented her to reach my nipples. At the same time, my child gagged when she got the hair in her mouth. She was about to vomit. After a while, when she asked to breastfeed again, I showed my breast with hair. She refused to breastfeed after seeing the hair.”

Another practice employed by 9.2% of the mothers to wean their children was to use a pacifier or a bottle. “When my child asked to breastfeed, I stopped her. I tried to give the pacifier or feeding bottle instead. My child cried for the first two days, and resisted to take the bottle. However, after three days, she took the bottle without any problem, and, after a day or two, she never asked to breastfeed again.”

None of the surveyed mothers had received consultation services from the relevant healthcare staff (family doctor, nurse, midwife, pediatrician) during the weaning phase. The results of this study revealed that all the mothers decided to stop breastfeeding based on their own personal experiences (Table 2).

Weaning practices of mothers.

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Deciding to wean | ||

| By themselves | 232 | 100.0 |

| Reason for weaning | ||

| Thinking that the duration of breastfeeding was sufficient | 61 | 26.3 |

| Thinking that her milk had gone dry | 56 | 24.1 |

| Thinking that the child had grown up | 40 | 17.2 |

| Conception | 37 | 15.9 |

| Child stopped to breastfeed | 16 | 6.9 |

| Othera | 22 | 10.5 |

| Status of using traditional methods for weaning | ||

| Yes | 131 | 56.5 |

| No | 101 | 43.5 |

| Traditional weaning practices (n=141)b | ||

| Applying tomato sauce, cayenne pepper, aloe vera, and salt on nipples to create a bad taste | 82 | 58.1 |

| Aversion by placing hair, cotton, and bandage on the breasts | 37 | 26.2 |

| Applying lipstick, nail polish, clay, or soot on the breasts to create a terrifying look | 19 | 13.5 |

| Using a pacifier or feeding bottle | 13 | 9.2 |

| Mean weaning duration (days) | 4.47±3.45 | |

As noted earlier, mother's milk is the most important nutrient for the child, as it meets both their psychological and physiological needs. For these reasons, there are programs aimed at encouraging mothers to breastfeed for the first two years and more.19 In this study, the mean breastfeeding duration was found to be higher than in other countries, and higher than the average for Turkey.2,11,20 This can be explained by the higher rate of literacy and awareness of the province of the study. As well as continuing breastfeeding, the process of weaning is also important. In this respect, the time and methods of weaning become a critical issue. In this study, mothers stated that they stopped breastfeeding because they felt it was time to do so; the child had breastfed long enough. Some mothers felt their milk had dried up, and others discovered they were pregnant. Other studies have reported the following reasons for weaning children: inadequate mother's milk, addition of solid foods to the child's diet after six months, child's refusal to breastfeed, adequate duration of breastfeeding, mother's employment, pregnancy, health problems, and use of pacifier or feeding bottle.15,19,21–24

The results of this study revealed that the all of the mothers decided to stop breastfeeding based on their own personal experiences and subjective approaches. Although the mean breastfeeding duration was nearly ideal in the present study, nurses and other health professionals could offer mothers a higher level of support when they decide to wean their children. In this study, none of the mothers had received counseling regarding the possible times and methods to terminate breastfeeding. Although breastfeeding counseling in Turkey encourages breastfeeding for two years, the importance of the weaning process has, unfortunately, been overlooked.

The most common practices used by study participants to begin weaning their children were to apply tomato paste, cayenne pepper, aloe vera, and salt on the breasts, place hair, cotton, and bandages on their breasts, and using a feeding bottle or pacifier to stop breastfeeding. These traditional methods were similar to some studies conducted in Turkey and some other countries. Women in Africa have been known to apply substances such as aloe leaves, ash, betel juice, bitter herbs, peppers, cactus, garlic, mud, soot, quinine, tobacco, and turmeric on their breasts in order to stop breastfeeding quickly by creating a bad taste. Mothers using these methods stated that their babies cried for one day and then stopped breastfeeding.14 Radwan reported that 25% of the mothers had applied lipstick, aloe vera, and bitter substances to the breasts.21 Piwoz et al. reported that mothers had wrapped their breasts with tight clothes to stop their child from breastfeeding.14 Dinç et al. reported that 33.1% of the mothers had applied peppers, tomato paste, lipstick, vaseline, coffee grounds, salt, bandages, mint leaves, broom fibers, or hair in order to wean their child.15 As seen in this recent study and other studies, some traditional methods such as creating a bad taste, making the breast scary to the child, preventing the suction of the children, and making breast access more difficult were used as weaning practices. Weaning is a critical phase in young children's development. The weaning practices used by mothers in eastern Turkey can be thought to pose traumatic risks in terms of mother–infant separation. This topic is not adequately addressed in the literature, and thus a proper comparison with other study findings was not possible. Since a mother's breasts are objects of trust for babies and young children, the abrupt weaning of children, as well as the images of blood or other fear-inducing images on the breasts may lead to ambivalent attitudes or feelings of alienation related to the female breast. Therefore, breastfeeding counseling services have become important in the termination phase of breastfeeding to support natural weaning.

Natural weaning begins when babies need for nursing has been fulfilled. Natural weaning occurs as the infant begins to accept increasing amounts and types of complementary feedings while still breastfeeding on demand between two and four years of age. Natural weaning is healthier than other methods for mother–baby attachment and separation.25 This process is less traumatic for mother and baby, since it occurs naturally according to the readiness level of mother and baby. Supporting the baby's nutritional needs with exclusive feeds and reducing the frequency of breastfeeding makes it easier for the baby spontaneously interrupt breastfeeding. For this reason, natural weaning should be supported by healthcare professionals.26

In the present study, participants breastfed for 19 months on average, decided when to terminate breastfeeding based on their personal experiences, and used mostly traditional methods for weaning. The results also revealed that some of the traditional methods used to wean a child can have traumatic effects. Therefore, the authors recommend to conduct more comprehensive and in-depth studies on this topic, as well as to add counseling for the weaning phase of the breastfeeding counseling programs.

Since the study was related to the termination of breastfeeding, only the mothers of 2–5-year-old children were included in the study; this sampling scope was extended due to the low fertility rate in the studied province. The study data is based on the testimonies of the mothers. Therefore, the memory bias is a limitation of the study.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The authors would like to thank the women who participated in the study.

Please cite this article as: Baş NG, Karatay G, Arikan D. Weaning practices of mothers in eastern Turkey. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2018;94:498–503.