The purpose of this study was to evaluate the agreement and risk factors for underestimation and overestimation between nutritional status and self-perceived body image and to assess the prevalence and associated factors for dissatisfaction with body weight among Brazilian adolescents.

MethodsStudents aged 12–17 years participating in the Study of Cardiovascular Risk in Adolescents (“ERICA”), a multicenter, cross-sectional, school-based country-wide study, were included (n=71,740). Variables assessed as covariates were sex, age, skin color, socioeconomic status, and common mental disorders (screened by the General Health Questionnaire, GHQ-12). Multinomial logistic regression was used to explore the association between covariates and combinations between self-perceived body image and body mass index (agreement, underestimation and overestimation). The associations between dissatisfaction with body weight and exposure variables were investigated using multivariable Poisson regression models.

ResultsApproximately 66% students rightly matched their body mass index with self-perceived weight (kappa coefficient was 0.38 for boys and 0.35 for girls). Agreement was higher among younger students and adolescents from low income households. Male sex, older age, and GHQ-12 score ≥3 were associated with weight overestimation. Prevalence of dissatisfaction with body weight was 45.0% (95% CI: 44.0–46.0), and higher among girls, older adolescents, those with underweight or overweight/obesity, as well as those who were physically inactive and with GHQ-12 ≥3.

ConclusionsMost of the sample rightly self-perceived their body image according to body mass index. Students with body image misperception and those dissatisfied with their weight were more likely to present a positive screening for common mental disorders.

A finalidade deste estudo foi avaliar a concordância e os fatores de risco para subestimação e superestimação entre o estado nutricional e a autoimagem corporal e para avaliar a prevalência e os fatores associados à insatisfação com o peso corporal entre adolescentes brasileiros.

MétodosForam incluídos estudantes entre 12 e 17 anos que participavam do Estudo de Riscos Cardiovasculares em Adolescentes (“ERICA”), um estudo multicêntrico, transversal, nacional e de base escolar (n=71.740). As variáveis analisadas como covariáveis foram sexo, idade, cor da pele, situação socioeconômica e transtornos mentais comuns (triados pelo Questionário de Saúde Geral, QSG-12). A regressão logística multinomial foi usada para explorar a associação entre as covariáveis e as combinações entre a autoimagem corporal e o índice de massa corporal (concordância, subestimação e superestimação). As associações entre a insatisfação com o peso corporal e as variáveis de exposição foram investigadas com os modelos multivariáveis de regressão de Poisson.

ResultadosAproximadamente 66% dos estudantes associaram corretamente seu índice de massa corporal com o peso autopercebido (o coeficiente kappa foi 0,38 para meninos e 0,35 para meninas). A concordância foi maior entre jovens e adolescentes de baixa renda. Sexo masculino, adolescentes mais velhos e um escore QSG 12 ≥3 foram associados à superestimação do peso. A prevalência de insatisfação com o peso corporal foi 45,0% (IC de 95%: 44,0-46,0), maior entre meninas, adolescentes mais velhos, aqueles abaixo do peso ou com sobrepeso/obesidade, fisicamente inativos e com QSG-12 ≥3.

ConclusõesA maior parte da amostra associou corretamente sua imagem corporal de acordo com o índice de massa corporal. Estudantes com distorção da autoimagem corporal e aqueles insatisfeitos com seu peso foram mais propensos a apresentar rastreamento positivo para transtornos mentais comuns.

Body image is a multidimensional construct involving self-perception on size and body shape, surrounded by the sensations and immediate experiences, also involving a subjective component that refers to individual satisfaction with body size.1 Media, family, and social environment may influence body image directly and indirectly.2 The interactions among these variables can promote unrealistic appearance and excessive comparisons with peers.2 Adolescents are most vulnerable to these influences because of their transition period, which is characterized by rapid growth and development as well as continuous changes in their bodies.

Body image is usually assessed by figure drawings or questionnaires, which are further classified based on satisfaction with one's own body.3 Most commonly based on cross-sectional studies, the prevalence of body dissatisfaction can be as high as 71% among adolescents, especially in female and overweight subjects.4 Others reported that the prevalence of body image dissatisfaction in developed countries ranges between 16% and 55% in boys and from 35% to 81% in girls.5 In Brazil, national data on this topic is scarce, and considering that body image may play an important role in managing and maintaining a healthy body weight, identifying which are the factors associated with distorted body image can be key in promoting a healthy weight at this age range.

Usually, girls aspire to become thinner while boys tend to desire an athletic body shape.6,7 Incorrect recognition of body weight status as well as negative body image is a threat to weight control as it may be associated with unhealthy behaviors and psychosocial morbidities.8,9 According to a prospective study carried out in the United States, a fourfold increased incidence of eating disorders was observed among female adolescents with body dissatisfaction.8 Adolescents dissatisfied with their body image commonly report more complaints of psychosocial health problems such as difficulty to sleep at night or nightmares, feeling nervous, stressed or depressed, having low self-esteem and low quality of life.9 Social pressures resulting in the discrepancy between actual, self-perceived and desired ideal body weight constitute a risk to mental health among adolescents.10

The purpose of this study is to evaluate the agreement between body weight self-perception and nutritional status in a large, nationwide sample of Brazilian adolescents enrolled in the Study of Cardiovascular Risk in Adolescents (ERICA). Furthermore, we sought to assess the risk factors for underestimation and overestimation between the BMI-for-age category and self-perceived body image, as well as to evaluate the prevalence and associated factors for dissatisfaction with body weight among Brazilian adolescents.

MethodsDesign and data collectionThe sample comprised adolescents participating in the ERICA, a multicenter, cross-sectional, school-based countrywide study. Data collection was held between February 2013 and November 2014.11 A total of 71,740 adolescents aged 12–17 years enrolled in public and private schools of 273 Brazilian municipalities with more than 100,000 inhabitants who have undergone assessment of anthropometric measures and fully completed the questionnaire were included. The response rate in the ERICA was 72% and further details can be found elsewhere.12

Details of the sampling procedures and data reliability are reported elsewhere.13 Briefly put, schools were selected with a proportional probability based on the number of students and inversely proportional to the distance between the municipality and the capital of the state. Clusters were selected at three levels: in the first level we selected schools as described above; in the second level we selected three classes per school with different combinations of scheduled time at school (morning and afternoon) and grades (from elementary to high school); and in the third level we considered classes. All students in the selected classes were invited to participate in the ERICA, signing the agreement of participation.11 The ERICA was approved by Research Ethics Committees in all 27 states in Brazil.

Self-reported variablesThe study protocol has been fully described elsewhere.11 Data were obtained by a self-administered structured questionnaire inserted into an electronic data collector (personal digital assistant – LG® GM750Q), with information on sociodemographic characteristics, physical activity level, common mental disorders (CMD), body image self-perception and body weight satisfaction.

To assess adolescents’ body weight satisfaction we used the following question: “Are you satisfied with your current body weight?” The answer options were “yes” or “no”. Those who answered “yes” in the last question were considered with “Ideal” body image self-perception. For those who answered “no” the following question was used: “In your opinion, how is your current body weight?” The answer options were “Below the ideal”, “Above the ideal” or “Far above the ideal”.

Screening for CMD was performed using the 12-item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12), an instrument that has 12 questions with four possible responses for each, and the respondents were asked to choose only one response that best fits how they have been feeling recently.14,15 The first two responses (“Not at all” and “No more than usual”) were scored zero, whereas the last two (“A little more than usual” and “Much more than usual”) were scored one point each. A score of zero on each item was considered negative, whereas a score of one point was considered positive for the presence of the symptom. This questionnaire is quick to administer and has psychometric properties comparable to its longer versions.16 A lower score represents a better health condition; a score equal or higher than three is indicative of positive screening for the presence of CMD.16

Physical activity was assessed with an adapted version of the Self-Administered Physical Activity Checklist,17 which consists of a list of 24 activities with moderate-to-vigorous intensity. Participants were asked to report the frequency (in days) and duration (in hours and minutes) of engagement in each of these activities during the last seven days. To determine the weekly amount of time spent in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA), we multiplied self-reported duration and frequency for each activity listed and then categorized them in <300min/week or ≥300min/week.18

The other variables assessed as covariates were sex, age (in full years), skin color (white, black, brown and others) and socioeconomic status, which was characterized using a similar criteria used in the Brazilian census,19 which includes data regarding consumer goods and parental education. The scores range from 0 to 46 and higher scores indicate higher socioeconomic status. This score was categorized into levels according to recommendation of the instrument: A (35–46 points), B (23–34 points), C (14–22 points), D (8–13 points) and E (0–7 points). Classes D and E were regrouped in the same category, due to low frequency.

Anthropometric measurementsAnthropometric measurements were obtained with individuals wearing light clothing and no shoes. Height (m) was measured using a calibrated stadiometer (stadiometer Alturexata®, Minas Gerais, Brazil). Weight (kg) was measured using a digital scale (model P150m, 200kg capacity, Líder®, São Paulo, Brazil). Body mass index (BMI) was calculated by weight (kg) divided by the squared height (m). The World Health Organization reference curves were used to classify the nutritional status, using the BMI-for-age according to sex.20 Cutoff values were as follows: malnutrition, BMI Z-score <−3; low weight, BMI Z-score ≥−3 and <−1; normal weight, BMI Z-score ≥−1 and ≤1; overweight, BMI Z-score >1 and ≤2; obesity, BMI Z-score >2.

Statistical analysisVariables were described using mean and standard deviation or prevalence and 95% confidence interval (CI). To compare means, Student's t test was used. For testing associations between categorical variables the Chi-squared test was performed.

To evaluate the agreement between self-perceived body image and nutritional status, categories were matched with nutritional status as follows: malnutrition or low weight=below the ideal; normal weight=ideal; overweight or obesity=above or far above the ideal. Kappa coefficient (k) was calculated to evaluate the degree of agreement between BMI categories and body image perception. The kappa coefficient is a measure of agreement: k=1 is perfect agreement, while k=0 represents no agreement beyond chance.

Multinomial logistic regression was used to explore the association between covariates and combinations between self-perceived body image and BMI (agreement, underestimation and overestimation). The adjusted models for sex, age, skin color, economic class, BMI, physical activity, and CMD were built with only one level of the input variables, which were taken from those with less influence to obtain the final model.

The associations between dissatisfaction with body weight and exposure variables were investigated using multivariable Poisson regression models.

All analyses were conducted in Stata 14.0 software with a significance level of 5%, by using the survey (svy) command to consider the expansion and complexity of sample design.

Ethics approval and consent to participateThis study was conducted according to the principles of the Helsinki declaration. Permission to conduct the study was obtained in all states and local Departments of Education and in all schools. All adolescents agreed in writing to participate in the study; five states also requested an informed consent form signed by the parent or legal guardian, according to the determination of the respective Research Ethics Committee or State Secretariat of Education.

ResultsSample characteristicsOf the 71,740 students evaluated, 95.0% were adolescents from state capitals, and 83.0% attended public schools. Girls accounted for 55.0% of the sample; 37.0% of the whole sample were in the 14–15 year-old age group; most reported brown (47.0%) or white (39.0%) skin color; and most came from families in the intermediate (B and C) economic classes (86.0%). Fifty-one percent of adolescents were considered physically active. Two and a half percent of the students were classified as underweight, 72.0% of students had normal weight, 17.0% were overweight, and 8.5% were obese. The GHQ-12 mean score was 2.10 (SE=0.25) points, and prevalence of a positive screening for CMD was 30.0%.

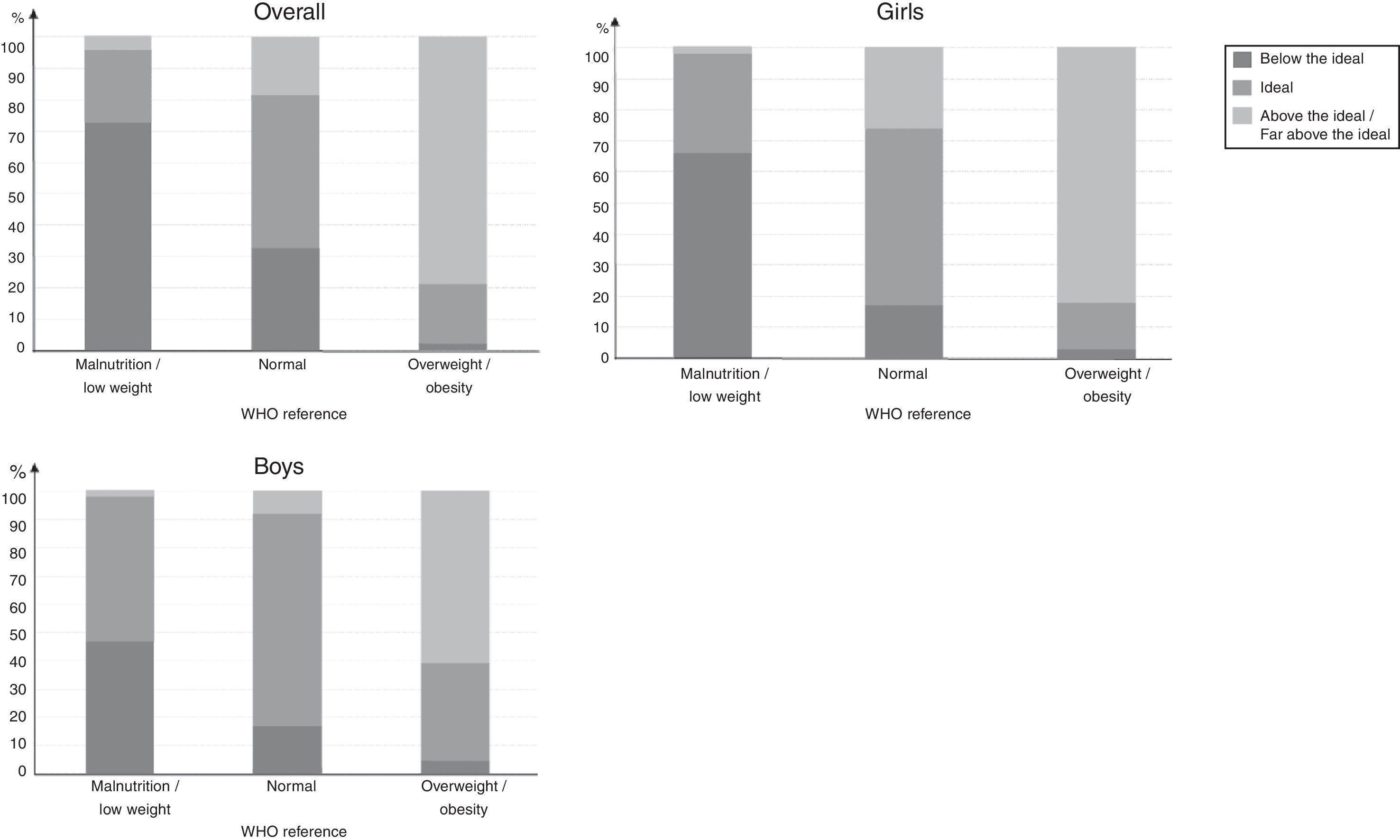

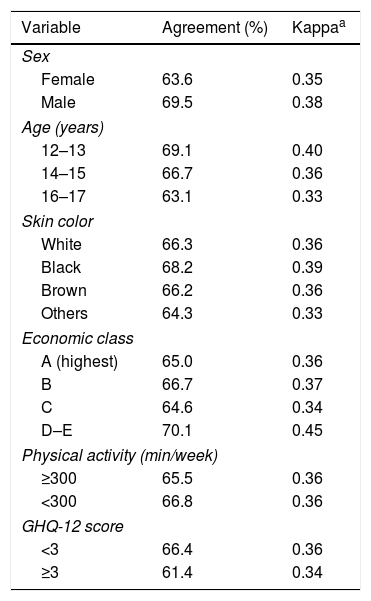

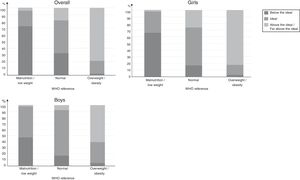

Agreement between self-perceived body image and measured BMIFig. 1 shows the distribution of self-perceived body image across BMI categories in the whole sample and by sex. Overall, adolescents with overweight/obesity were those who better recognize their body image. On the other hand, adolescents with underweight showed a higher prevalence of body image misperception. Sixty-six percent of adolescents rightly matched their BMI-for-age category with their self-perceived body image (kappa=0.37). In general, the agreement between self-perceived body image and measured BMI was reasonable, as showed in Table 1.

Agreement between BMI-for-age category and self-perceived body weight. ERICA, Brazil, 2013–2014.

| Variable | Agreement (%) | Kappaa |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | 63.6 | 0.35 |

| Male | 69.5 | 0.38 |

| Age (years) | ||

| 12–13 | 69.1 | 0.40 |

| 14–15 | 66.7 | 0.36 |

| 16–17 | 63.1 | 0.33 |

| Skin color | ||

| White | 66.3 | 0.36 |

| Black | 68.2 | 0.39 |

| Brown | 66.2 | 0.36 |

| Others | 64.3 | 0.33 |

| Economic class | ||

| A (highest) | 65.0 | 0.36 |

| B | 66.7 | 0.37 |

| C | 64.6 | 0.34 |

| D–E | 70.1 | 0.45 |

| Physical activity (min/week) | ||

| ≥300 | 65.5 | 0.36 |

| <300 | 66.8 | 0.36 |

| GHQ-12 score | ||

| <3 | 66.4 | 0.36 |

| ≥3 | 61.4 | 0.34 |

BMI, body mass index; ERICA, Study of Cardiovascular Risks in Adolescents; GHQ-12, General Health Questionnaire.

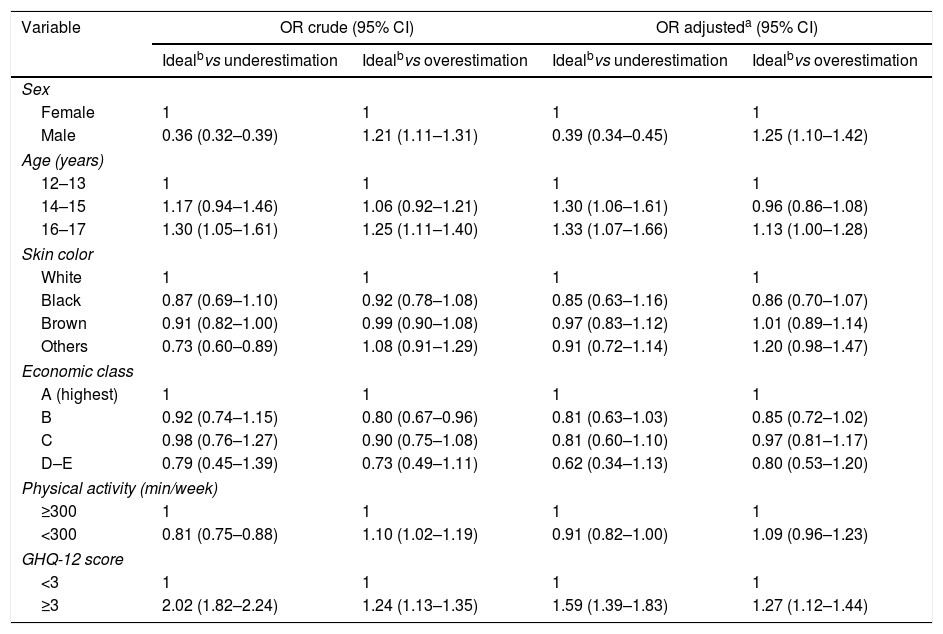

In the sample, approximately 20.0% of the adolescents overestimated and 13.5% underestimated their actual weight status. Table 2 shows the associated factors with body image misperception. Boys were more likely to overestimate their body image compared to girls. Analyzing by age, older adolescents (16–17 years) were more likely to present a body image misperception when compared to younger adolescents. A positive screening for CMD increases the odds ratio for both overestimation and underestimation of self-perceived body image.

Multinomial logistic regression analysis of variables associated with underestimation and overestimation between BMI-for-age category and self-perceived body image. ERICA, Brazil, 2013–2014.

| Variable | OR crude (95% CI) | OR adjusteda (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Idealbvs underestimation | Idealbvs overestimation | Idealbvs underestimation | Idealbvs overestimation | |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Male | 0.36 (0.32–0.39) | 1.21 (1.11–1.31) | 0.39 (0.34–0.45) | 1.25 (1.10–1.42) |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 12–13 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 14–15 | 1.17 (0.94–1.46) | 1.06 (0.92–1.21) | 1.30 (1.06–1.61) | 0.96 (0.86–1.08) |

| 16–17 | 1.30 (1.05–1.61) | 1.25 (1.11–1.40) | 1.33 (1.07–1.66) | 1.13 (1.00–1.28) |

| Skin color | ||||

| White | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Black | 0.87 (0.69–1.10) | 0.92 (0.78–1.08) | 0.85 (0.63–1.16) | 0.86 (0.70–1.07) |

| Brown | 0.91 (0.82–1.00) | 0.99 (0.90–1.08) | 0.97 (0.83–1.12) | 1.01 (0.89–1.14) |

| Others | 0.73 (0.60–0.89) | 1.08 (0.91–1.29) | 0.91 (0.72–1.14) | 1.20 (0.98–1.47) |

| Economic class | ||||

| A (highest) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| B | 0.92 (0.74–1.15) | 0.80 (0.67–0.96) | 0.81 (0.63–1.03) | 0.85 (0.72–1.02) |

| C | 0.98 (0.76–1.27) | 0.90 (0.75–1.08) | 0.81 (0.60–1.10) | 0.97 (0.81–1.17) |

| D–E | 0.79 (0.45–1.39) | 0.73 (0.49–1.11) | 0.62 (0.34–1.13) | 0.80 (0.53–1.20) |

| Physical activity (min/week) | ||||

| ≥300 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| <300 | 0.81 (0.75–0.88) | 1.10 (1.02–1.19) | 0.91 (0.82–1.00) | 1.09 (0.96–1.23) |

| GHQ-12 score | ||||

| <3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| ≥3 | 2.02 (1.82–2.24) | 1.24 (1.13–1.35) | 1.59 (1.39–1.83) | 1.27 (1.12–1.44) |

BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; ERICA, Study of Cardiovascular Risks in Adolescents; GHQ-12, General Health Questionnaire; OR, odds ratio.

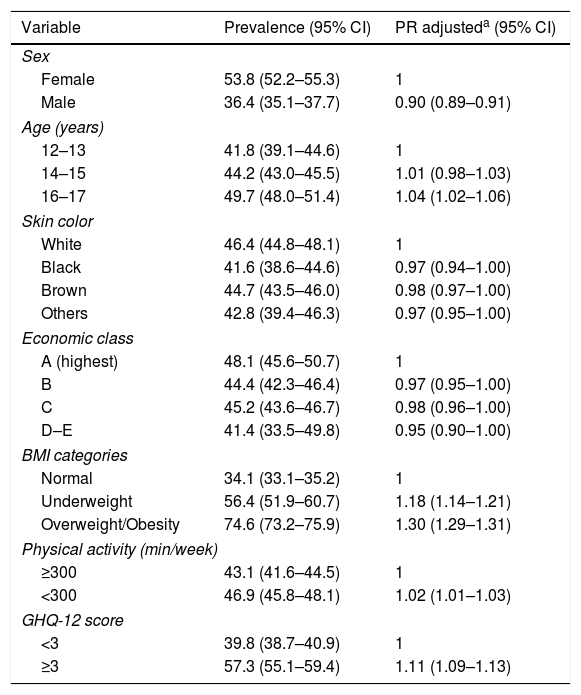

The prevalence of adolescents dissatisfied with their body weight was 45.0% (95% CI 44.0–46.0). Table 3 summarizes the prevalence and prevalence ratios of adolescents dissatisfied with their body weight according to independent variables. Girls reported dissatisfaction with their body weight more frequently than boys. Significant higher adjusted prevalence ratios for body dissatisfaction were observed in older adolescents, those with underweight or overweight/obesity, those who were physically inactive and with positive score for CMD.

Prevalence and prevalence ratios of adolescents dissatisfied with their body weight according to covariates. ERICA, Brazil, 2013–2014.

| Variable | Prevalence (95% CI) | PR adjusteda (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | 53.8 (52.2–55.3) | 1 |

| Male | 36.4 (35.1–37.7) | 0.90 (0.89–0.91) |

| Age (years) | ||

| 12–13 | 41.8 (39.1–44.6) | 1 |

| 14–15 | 44.2 (43.0–45.5) | 1.01 (0.98–1.03) |

| 16–17 | 49.7 (48.0–51.4) | 1.04 (1.02–1.06) |

| Skin color | ||

| White | 46.4 (44.8–48.1) | 1 |

| Black | 41.6 (38.6–44.6) | 0.97 (0.94–1.00) |

| Brown | 44.7 (43.5–46.0) | 0.98 (0.97–1.00) |

| Others | 42.8 (39.4–46.3) | 0.97 (0.95–1.00) |

| Economic class | ||

| A (highest) | 48.1 (45.6–50.7) | 1 |

| B | 44.4 (42.3–46.4) | 0.97 (0.95–1.00) |

| C | 45.2 (43.6–46.7) | 0.98 (0.96–1.00) |

| D–E | 41.4 (33.5–49.8) | 0.95 (0.90–1.00) |

| BMI categories | ||

| Normal | 34.1 (33.1–35.2) | 1 |

| Underweight | 56.4 (51.9–60.7) | 1.18 (1.14–1.21) |

| Overweight/Obesity | 74.6 (73.2–75.9) | 1.30 (1.29–1.31) |

| Physical activity (min/week) | ||

| ≥300 | 43.1 (41.6–44.5) | 1 |

| <300 | 46.9 (45.8–48.1) | 1.02 (1.01–1.03) |

| GHQ-12 score | ||

| <3 | 39.8 (38.7–40.9) | 1 |

| ≥3 | 57.3 (55.1–59.4) | 1.11 (1.09–1.13) |

BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; ERICA, Study of Cardiovascular Risks in Adolescents; GHQ-12, General Health Questionnaire; PR, prevalence ratio.

In this study, three out of ten Brazilian students showed misperception about their body image, which was associated with sex, age and a positive screening for CMD. We also observed that the degree of agreement between BMI categories and self-perceived body image was moderate. In addition, 45% of the adolescents reported dissatisfaction with their body weight, an observation that was more frequent among girls, older adolescents, those who were classified as underweight, overweight or obese, those who were physically inactive, and with a positive screening for CMD.

Despite the importance of self-perceived body image for psychological and general health, few studies have investigated the agreement between different measurements of self-perceived body image and nutritional status according to BMI, especially in adolescents from developing countries. In our study, the higher kappa coefficients were observed in younger students and adolescents from lower-income families (classes D–E). A previous study also reported a lower discordant weight perception among younger adolescents; however, low income was a risk factor for dissatisfaction, especially among girls.21 Our results may be different from previous observational studies because we used data from a developing country with pronounced inequalities. Therefore, body image in minorities should be further explored in order to better understand the peculiarities of these groups and their relationship with body satisfaction during adolescence.

We observed that boys were significantly more likely to overestimate their current weight status, while girls were more likely to underestimate it. These findings are in accordance with previous studies about body image misperception among adolescents.10 However, another study involving 6863 Chinese adolescents from middle and high school classes found that girls more often considered themselves to be heavier in relation to their male counterparts.22 The increased adiposity during puberty may play a role for higher dissatisfaction among girls compared to boys.23 Other factors like body reference images commonly used in mass media and more recently in social media can affect how adolescents perceive themselves, and consequently influence the desire of women and men in relation to the ideal body shape in different cultures.24

In this study, the positive screening for CMD was related with body image misperception and body weight dissatisfaction. Body weight dissatisfaction was 10% more frequent in adolescents with CMD; in addition, these students are more likely to underestimate (59%) and overestimate (27%) their self-perceived body image. One out of three adolescents showed a positive screening for CMD in ERICA, similarly to what was observed in a previous study from a developing country.25 Another study involving Brazilian adolescents observed a higher prevalence of CMD among those unsatisfied with their body weight, especially for those desiring to be fatter.26 More recently, in addition to the classical pathway described to link obesity and CMD, another suggestion was that body image could mediate this association.27 Thus, the role of body image and body satisfaction in the development of CMD among adolescents should be further investigated.

It is challenging to determine what levels of body weight dissatisfaction should be considered acceptable among adolescents. The prevalence of dissatisfaction described in our study was relatively higher as compared to that of developed countries.28 Nonetheless, we observed that female sex, higher age, BMI extremes (underweight and overweight), physical inactivity, and CMD were associated with body weight dissatisfaction. The associations between body weight dissatisfaction with female sex and overweight/obesity in adolescents are already well established.28 In relation to physical activity, most published studies suggest that being physically active is associated with better overall self-esteem.29 However, the association of physical activity with body satisfaction is probably dependent on body weight; specifically, body weight seems to have a greater effect when physical activity levels are low; however, this effect could be reduced with an increase in physical activity levels.

Our study has some limitations. This study reports cross-sectional findings, thus not being able to establish cause-effect relationships. Secondly, self-administered questionnaires were used to access some of the covariates (i.e. CMD and physical activity). It is also important to note that in the case of the questionnaire used to screen CMD, diagnosis was not possible. The use of questionnaires could introduce bias; however, non-differential measurement error commonly attenuates rather than increases the apparent magnitude of associations. Finally, as multinomial logistic regression analysis defines one reference group to the detriment of all others, this could be considered a limitation.

Evidently, the strength of this study is its large representative sample from a developing country. Furthermore, actual weight and height were measured by trained interviewers through standardized protocols. Our study extends previous observations analyzing data from a multiethnic sample of adolescents from a developing country, especially if we consider that cultural and economic variables play a role in body image perception. Also, our observations may have implications for public health. We observed that both misperception and dissatisfaction with body weight were associated with positive screening for CMD, which commonly starts during adolescence. Thus, body image should be considered in interventions aimed to improve mental health among adolescents.

In Brazilian adolescents, a moderate agreement between actual weight status and self-perceived body image was found. Overweight/obese adolescents showed higher proportion of correct body image self-perception, while boys were more likely than girls to overestimate their current weight status, and girls were more likely to underestimate their current weight status. Students with body image misperception and those dissatisfied with their body weight were more likely to present a positive screening for CMD. These findings highlight the association between body dissatisfaction and psychological well-being and underscore the importance of including mental health assessment in adolescents reporting a misperception about their body image. Prospective studies are required in order to establish what levels of body dissatisfaction are worrisome among adolescents, as well as the influence of age, gender, ethnicity, and CMD. The identification of these factors may support the development of health system prevention programs in Brazil and other middle-income countries.

FundingThis study was supported by the Brazilian Ministry of Health (Science and Technology Department) and the Brazilian Ministry of Science and Technology (Financiadora de Estudos e Projetos – Finep and Conselho Nacional de Pesquisa – CNPq) (grants: Finep: 01090421; CNPq: 565037/2010-2 and 405009/2012-7); and by the Fundo de Incentivo à Pesquisa do Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre (FIPE – HCPA – Process: 09-098).

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Dr. Kieling and Dr. Schaan have received support from Brazilian governmental research funding agencies (Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico – CNPq, Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – Capes, and Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul – FAPERGS). Dr. Kieling has also received authorship royalties from Brazilian publishers Artmed and Manole.

Please cite this article as: Moehlecke M, Blume CA, Cureau FV, Kieling C, Schaan BD. Self-perceived body image, dissatisfaction with body weight and nutritional status of Brazilian adolescents: a nationwide study. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2020;96:76–83.