To analyze the prevalence of excess weight and low height, and identify associated factors among children younger than five years.

MethodsCross-census study. A total of 1,640 children from two municipalities in Piauí, Brazil were included.

ResultsThe prevalence of low height was 10.9% (95% CI: 9.3 to 12.4), inversely associated with mother's younger age and low level of education, lower socioeconomic status, mothers who had fewer than six prenatal consultations, and households that had more than one child younger than 5 years. Excess weight prevalence was 19.1% (95% CI: 17.2 to 21.0), and remained inversely associated with lower maternal age, low maternal education, and cesarean delivery. Stunting was greater in children aged between 12 and 23 months, while excess weight decreased with age.

ConclusionsIt is noteworthy that the stunting rate, although decreasing, is still high, while the prevalence of excess weight, even in this very poor area, already exceeds the expected percentage for a population with better socioeconomic level.

Analisar a prevalência de excesso de peso e déficit de altura e identificar fatores associados entre menores de cinco anos.

MétodosEstudo censitário transversal. Foram incluídas 1.640 crianças de dois municípios do Piauí, Brasil.

ResultadosA prevalência de déficit de altura foi 10,9% (IC95%: 9,3–12,4), inversamente associado com menor idade e escolaridade materna, menor condição socioeconômica, as mães que realizaram menos de 6 consultas pré-natal e se nessas casas haviam mais de uma criança menor de cinco anos. O excesso de peso teve prevalência de 19,1% (IC95%: 17,2–21,0), e manteve-se inversamente associado com menor idade da mãe, baixa escolaridade materna e parto cesáreo. O déficit de altura foi maior para crianças entre 12 e 23 meses, enquanto o excesso de peso diminuiu com a idade.

ConclusõesDestaca-se que o déficit de altura, embora esteja diminuindo, ainda é elevado, enquanto a prevalência de excesso de peso, mesmo nesta área muito pobre, já supera o percentual esperado para uma população com melhores condições socioeconômicas.

Brazil is still experiencing a nutritional transition phase, characterized by marked reduction in the prevalence of malnutrition and increased frequency of overweight. However, there have been very few studies in Brazil1 that have investigated stunting and overweight in the same population of children younger than 5 years. It is noteworthy that both deficits and excess are detrimental to health, causing both physical and cognitive damage to child development. Inadequate child development affects learning and makes the child more vulnerable to several diseases, particularly the cardiovascular and metabolic.1

Anthropometric monitoring is necessary, as early identification of both stunting and excess weight allow interventions to be conducted in order to prevent changes throughout life and enable full development in childhood and in the next phases of the life cycle.2

Data from the National Demographic and Health Survey show that between 1996 and 2006 there was a decrease in the prevalence of stunting for age from 13.4% to 6.7%, while the weight deficit for age decreased from 4.2% to 1.8%.3 In this same period, there was a decrease in weight deficit for height, from 2.2% in 1996 to 1.5% in 2006, and virtual stability in the prevalence of excess for this indicator of approximately 7% in the two years (2004-2006).3 In summary, in the comparison of the time period evaluated, there was substantial reduction in the risk of child malnutrition in Brazil, with no evidence of temporal variation in the risk of obesity.3

The Household Budget Survey for the year 2008-2009 in children younger than 5 years showed the Northeast region as the region with the second highest weight for age deficit (5.9%) in the country, second only to the North region (8.5%).4 Regarding the prevalence of excess weight, it ranged from 25% to 30% in the North and Northeast regions (more than five times the prevalence of weight deficit), and from 32% to 40% in Southeast, South, and Midwest (more than ten times the prevalence of weight deficit). Excess weight tended to be more frequent in urban than in rural areas, particularly in the North, Northeast, and Midwest regions.4

Considering the environmental aspects identified as the most important factors that contribute to the nutritional aspect, especially among children and adolescents, the need to carry out regionalized population-based studies to discuss the specific characteristics and context of the nutrition transition that Brazil is experiencing is emphasized.5 Thus, the aim of this study was to analyze the prevalence of excess weight and stunting, and to identify associated factors in children younger than 5 years.

MethodsThis is was census-based, cross-sectional study, which is part of a project entitled “Health of Children younger than 5 Years and Adolescents Residing in the Municipalities of Caracol and Anísio de Abreu, PI”. The towns of Caracol and Anísio de Abreu are located in the southeast of the state of Piauí. Piauí is considered one of the poorest states in Brazil. Its economy is centered on agriculture, and the human development index (HDI) is 0.7.6,7

Participants that were eligible for the study included all children aged 0 to 59 months, residing in urban and rural areas of these towns between July and September of 2008.

Due to the need to identify associated factors, sample size was calculated a posteori, as this research was not initially designed for this purpose. The prevalence of excess weight use was 30% (> +1 Z-scores for weight/height indicator) and the remaining parameters used were as follows: alpha error of 0.05, beta error of 0.20, exposures ranging from 20% to 80%, outcome frequency among the non-exposed of at least 13%, and hazard ratio of 1.7. Thus, the study would require a sample of at least 1,293 children. This figure already includes 5% for losses and 15% for the control of potential confounders.

The data collection tool consisted of two questionnaires about the child and the mother, applied by previously selected interviewers who had been trained for this purpose to the child's mother or guardian. Data were collected on sociodemographic conditions, assistance received during pregnancy and childbirth, breastfeeding, and health service use. At the time of interview, the child's weight (portable scale with a precision of 100 grams provided by the United Nations Children's and Adolescents’ Fund (UNICEF) and height (aluminum stadiometers with a precision of 1mm) or length (Harpenden infantometer with 1mm precision) were measured, the latter used in infants younger than 2 years of age.

For data collection, 14 students who had finished high school or were undergraduate students in the humanities at Universidade Estadual do Piauí (UESPI), Campus de São Raimundo Nonato were pre-selected. These students were trained for five consecutive days, eight hours per day. The training consisted of reading the questionnaire and instruction manual, simulated interviews, and standardization of anthropometric techniques. After this stage, eight were selected and hired to perform the interviews. Two graduates in social sciences, with extensive experience in this type of study, were previously assigned as supervisors. The pilot study was carried out in the municipality of São Raimundo Nonato, located in the same region as the two towns included in the study.

Two teams consisting of a supervisor and four interviewers were created. Each team was responsible for data collection in one of these municipalities. The first step was to map and number the street blocks in urban areas and villages in the rural area. Each pair of interviewers went through all households, clockwise, looking for children younger than 5 years. When a household had children in this age group, the questionnaires were then applied to the child's mother or guardian.

These questionnaires were coded by interviewers at the end of each day, and on the following day, they were handed to their respective supervisors, who sent them to the project headquarters. Each of these questionnaires was revised and typed in duplicate in reverse order, by two fellows. After entering each block of 100 questionnaires, databases were compared and if necessary, corrected. The software used for data tabulation was Epi-Info 6.04 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), GA,USA).8

The dependent variables were stunting and excess weight. Low height for age (Z-score<-2), whether the length in the case of children younger than 2 years (measured with the subject lying down) or height for children 2 years or older (measured with the individual standing) was evaluated according to recommended methods and recorded in centimeters. The child's age was calculated in months and overweight as BMI for age Z-score>1.9

The independent variables were: Municipality (Caracol and Anísio de Abreu), area (rural or urban), whether the mother had a partner (yes or no), mother's level of schooling (0-4 years, 5-8 years, or 9 or more years), whether there was more than one child younger than 5 years in the household (yes or no), whether the mother had six or more prenatal consultations (yes or no), type of delivery (normal or caesarean), exclusive breastfeeding (< 1 month, 1-3 months and 29 days, or ≥ 4 months), whether the child had a consultation in the last 3 months (yes or no), and consumer goods index (created based on the analysis of the main components of seven characteristics of the household and ownership of household goods,4 and subsequently divided into tertiles from lowest to highest).

The data analysis was conducted using Stata software, release 11.1. Poisson regression with robust adjustment of variance was used for unadjusted and adjusted analyses. A p-value of 5% was used as the significance level for two-tailed tests. The hierarchical model, created for the multivariate analysis, was constructed using sociodemographic factors (including municipality, area, mother's age, mother's and child's ethnicity, whether the mother had a partner, mother's level of schooling, socioeconomic status, number of children younger than 5 years of age in the household) in the first level, whereas the second level included the care received during pregnancy and childbirth (prenatal, childbirth, and child height), the third level included the pattern of breastfeeding and diet (breastfeeding and duration of breastfeeding), and the fourth level included the use of health services (consultation in the past three months with a physician and/or nurse).

The study was approved by the Ethics and Research Committee of Universidade Federal de Pelotas (Resolution No. 001/08), in accordance with the current regulations for human research, and the questionnaire was applied only after the informed consent had been explained to and signed by the interviewee.

ResultsA total of 1,640 children younger than 5 years of age from the two municipalities were included in the study. Of this total, information was obtained from approximately 99% of them in Caracol and 97% in Anísio Abreu. The overall rate of non-responders was 4.0% (65/1,640).

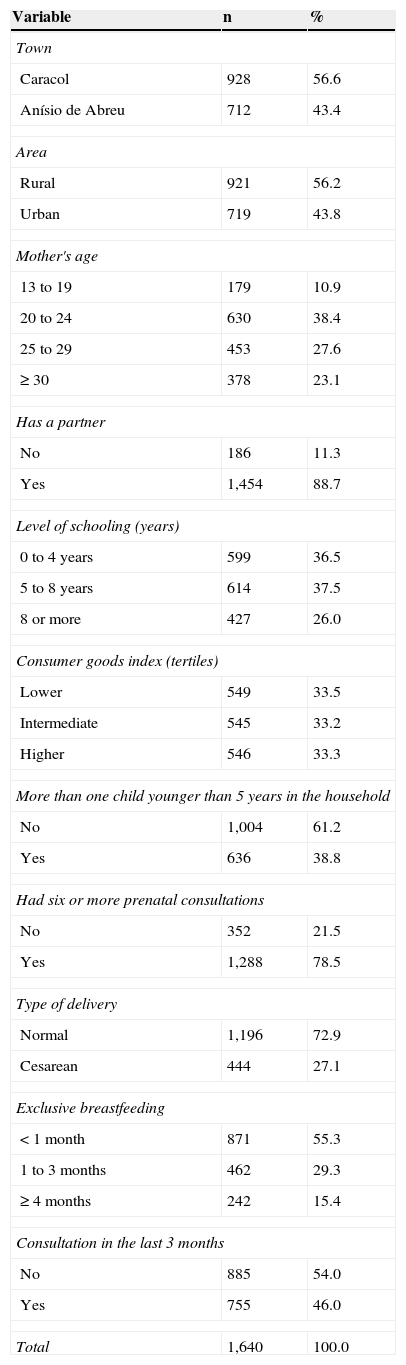

Table 1 shows the sample description. Children who lived in Caracol had a higher prevalence (56.6%), their mothers’ mean age was 26.2 years (SD=7.3), and level of schooling was 0-4 years (36.5%). Households with more than one child younger than 5 years showed a prevalence of 38.8%. Regarding pregnancy, 78.5% of the mothers had six or more prenatal consultations, 72.9% had the last child vaginally, and 55.3% of them exclusively breastfed their children for less than one month. In the last three months, (46.0%) of these mothers had taken the child to a consultation with a doctor or nurse.

Sample description according to the analyzed characteristics (Piauí, Brazil, 2010).

| Variable | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Town | ||

| Caracol | 928 | 56.6 |

| Anísio de Abreu | 712 | 43.4 |

| Area | ||

| Rural | 921 | 56.2 |

| Urban | 719 | 43.8 |

| Mother's age | ||

| 13 to 19 | 179 | 10.9 |

| 20 to 24 | 630 | 38.4 |

| 25 to 29 | 453 | 27.6 |

| ≥ 30 | 378 | 23.1 |

| Has a partner | ||

| No | 186 | 11.3 |

| Yes | 1,454 | 88.7 |

| Level of schooling (years) | ||

| 0 to 4 years | 599 | 36.5 |

| 5 to 8 years | 614 | 37.5 |

| 8 or more | 427 | 26.0 |

| Consumer goods index (tertiles) | ||

| Lower | 549 | 33.5 |

| Intermediate | 545 | 33.2 |

| Higher | 546 | 33.3 |

| More than one child younger than 5 years in the household | ||

| No | 1,004 | 61.2 |

| Yes | 636 | 38.8 |

| Had six or more prenatal consultations | ||

| No | 352 | 21.5 |

| Yes | 1,288 | 78.5 |

| Type of delivery | ||

| Normal | 1,196 | 72.9 |

| Cesarean | 444 | 27.1 |

| Exclusive breastfeeding | ||

| < 1 month | 871 | 55.3 |

| 1 to 3 months | 462 | 29.3 |

| ≥ 4 months | 242 | 15.4 |

| Consultation in the last 3 months | ||

| No | 885 | 54.0 |

| Yes | 755 | 46.0 |

| Total | 1,640 | 100.0 |

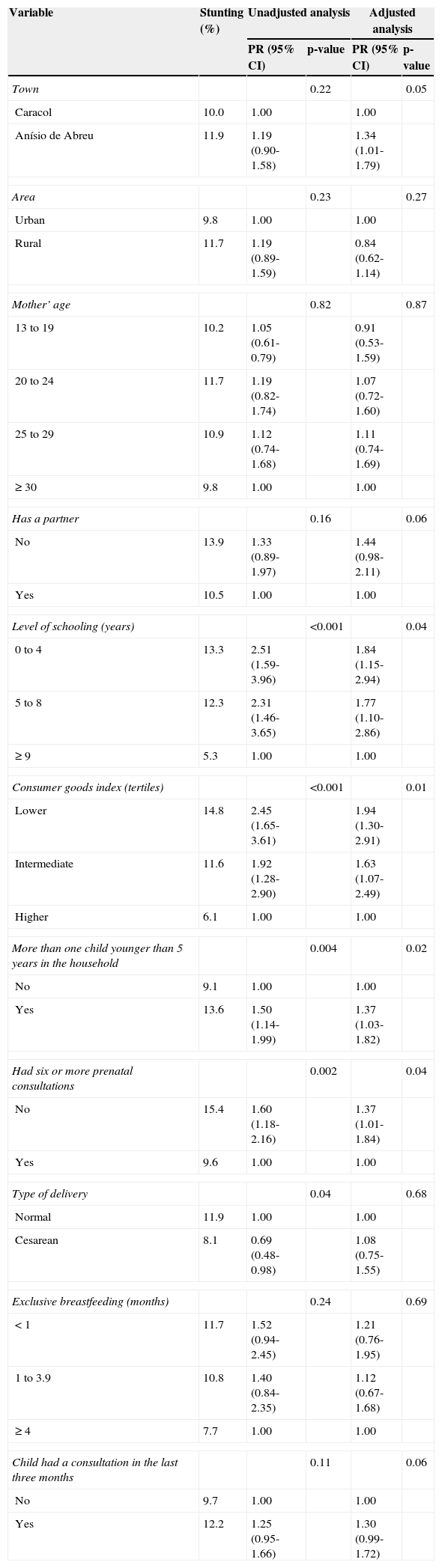

The prevalence of stunting was 10.9% (95% CI: 9.3 to 12.4). This prevalence was higher for children whose mothers had 0-4 years of schooling, 13.3% (95% CI 1.59 to 3.96); were poorer, 14.8% (95% CI 1.65 to 3.61); had more than one child younger than 5 years at home, 13.6% (95% CI 1.14 to 1.99); and in the group with a lower number of prenatal consultations (< 6), 15.4% (95% CI 1.18 to 2.16) (Table 2). In the adjusted analysis, the mother's level of schooling, consumer goods index, and number of prenatal consultations remained inversely associated with stunting. The number of children younger than 5 in the household also were demonstrated to be inversely associated with stunting.

Unadjusted and adjusted analysis of stunting with the other variables (Piauí, Brazil, 2010).

| Variable | Stunting (%) | Unadjusted analysis | Adjusted analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PR (95% CI) | p-value | PR (95% CI) | p-value | ||

| Town | 0.22 | 0.05 | |||

| Caracol | 10.0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Anísio de Abreu | 11.9 | 1.19 (0.90-1.58) | 1.34 (1.01-1.79) | ||

| Area | 0.23 | 0.27 | |||

| Urban | 9.8 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Rural | 11.7 | 1.19 (0.89-1.59) | 0.84 (0.62-1.14) | ||

| Mother’ age | 0.82 | 0.87 | |||

| 13 to 19 | 10.2 | 1.05 (0.61-0.79) | 0.91 (0.53-1.59) | ||

| 20 to 24 | 11.7 | 1.19 (0.82-1.74) | 1.07 (0.72-1.60) | ||

| 25 to 29 | 10.9 | 1.12 (0.74-1.68) | 1.11 (0.74-1.69) | ||

| ≥ 30 | 9.8 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Has a partner | 0.16 | 0.06 | |||

| No | 13.9 | 1.33 (0.89-1.97) | 1.44 (0.98-2.11) | ||

| Yes | 10.5 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Level of schooling (years) | <0.001 | 0.04 | |||

| 0 to 4 | 13.3 | 2.51 (1.59-3.96) | 1.84 (1.15-2.94) | ||

| 5 to 8 | 12.3 | 2.31 (1.46-3.65) | 1.77 (1.10-2.86) | ||

| ≥ 9 | 5.3 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Consumer goods index (tertiles) | <0.001 | 0.01 | |||

| Lower | 14.8 | 2.45 (1.65-3.61) | 1.94 (1.30-2.91) | ||

| Intermediate | 11.6 | 1.92 (1.28-2.90) | 1.63 (1.07-2.49) | ||

| Higher | 6.1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| More than one child younger than 5 years in the household | 0.004 | 0.02 | |||

| No | 9.1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 13.6 | 1.50 (1.14-1.99) | 1.37 (1.03-1.82) | ||

| Had six or more prenatal consultations | 0.002 | 0.04 | |||

| No | 15.4 | 1.60 (1.18-2.16) | 1.37 (1.01-1.84) | ||

| Yes | 9.6 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Type of delivery | 0.04 | 0.68 | |||

| Normal | 11.9 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Cesarean | 8.1 | 0.69 (0.48-0.98) | 1.08 (0.75-1.55) | ||

| Exclusive breastfeeding (months) | 0.24 | 0.69 | |||

| < 1 | 11.7 | 1.52 (0.94-2.45) | 1.21 (0.76-1.95) | ||

| 1 to 3.9 | 10.8 | 1.40 (0.84-2.35) | 1.12 (0.67-1.68) | ||

| ≥ 4 | 7.7 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Child had a consultation in the last three months | 0.11 | 0.06 | |||

| No | 9.7 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 12.2 | 1.25 (0.95-1.66) | 1.30 (0.99-1.72) | ||

PR, prevalence ratio.

Cesarean delivery, which was a protective factor, lost its association, and the municipality of Anísio Abreu started to show a higher prevalence when adjusted for demographic and socioeconomic variables. Children that had a consultation in the last three months had a borderline association with stunting (p=0.06). This outcome occurred more frequently in children between 1 and 2 years of age, and was lower in those younger than 1 year.

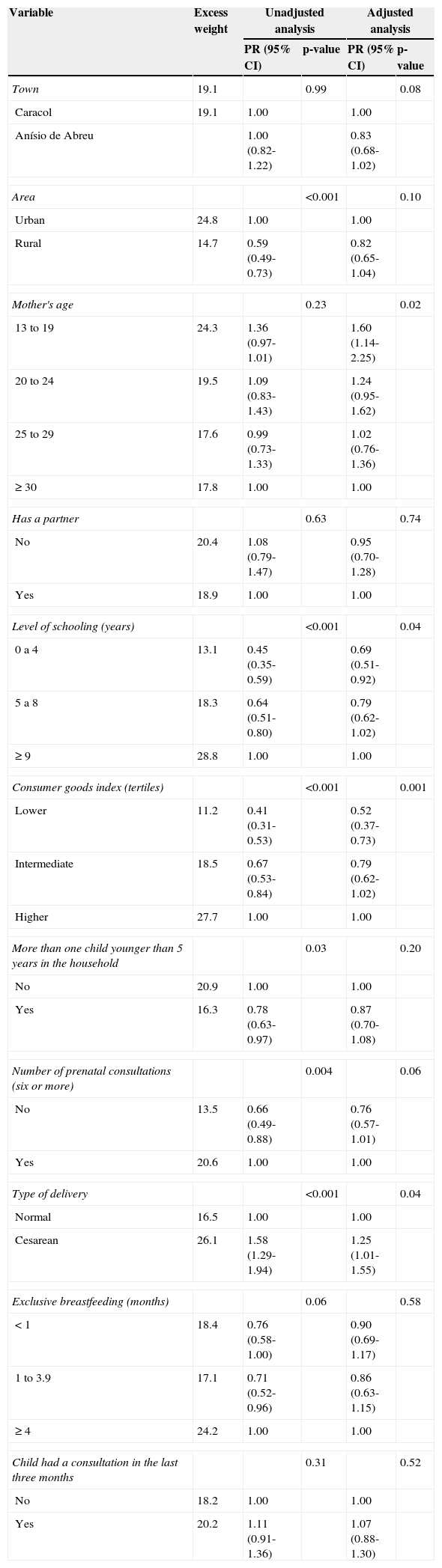

Excess weight prevalence was 19.1% (95% CI: 17.2 to 21.0), similar in both municipalities. Lower maternal level of schooling (0 to 4 years), 13.1% (95% CI: 0.35 to 0.59); lower socioeconomic status, 11.2% (95% CI 0.31 to 0.53); having more than one child younger than 5 years at home 16.3% (95% CI: 0.63 to 0.97); and the group with a lower numbers of prenatal consultations (< 6) 13.5% (95% CI 0.49 to 0.88) were protective factors for excess weight in the unadjusted analysis, and cesarean delivery had a negative association, 26.1% (95% CI: 1.29 to 1.94; Table 3). In the adjusted analysis, area of residence, ethnicity, number of children younger than 5 years, and prenatal consultations lost the association. Higher level of schooling, higher consumer goods index, and cesarean section remained associated with excess weight.

Unadjusted and adjusted analysis of excess weight with the other variables (Piauí, Brazil, 2010).

| Variable | Excess weight | Unadjusted analysis | Adjusted analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PR (95% CI) | p-value | PR (95% CI) | p-value | ||

| Town | 19.1 | 0.99 | 0.08 | ||

| Caracol | 19.1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Anísio de Abreu | 1.00 (0.82-1.22) | 0.83 (0.68-1.02) | |||

| Area | <0.001 | 0.10 | |||

| Urban | 24.8 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Rural | 14.7 | 0.59 (0.49-0.73) | 0.82 (0.65-1.04) | ||

| Mother's age | 0.23 | 0.02 | |||

| 13 to 19 | 24.3 | 1.36 (0.97-1.01) | 1.60 (1.14-2.25) | ||

| 20 to 24 | 19.5 | 1.09 (0.83-1.43) | 1.24 (0.95-1.62) | ||

| 25 to 29 | 17.6 | 0.99 (0.73-1.33) | 1.02 (0.76-1.36) | ||

| ≥ 30 | 17.8 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Has a partner | 0.63 | 0.74 | |||

| No | 20.4 | 1.08 (0.79-1.47) | 0.95 (0.70-1.28) | ||

| Yes | 18.9 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Level of schooling (years) | <0.001 | 0.04 | |||

| 0 a 4 | 13.1 | 0.45 (0.35-0.59) | 0.69 (0.51-0.92) | ||

| 5 a 8 | 18.3 | 0.64 (0.51-0.80) | 0.79 (0.62-1.02) | ||

| ≥ 9 | 28.8 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Consumer goods index (tertiles) | <0.001 | 0.001 | |||

| Lower | 11.2 | 0.41 (0.31-0.53) | 0.52 (0.37-0.73) | ||

| Intermediate | 18.5 | 0.67 (0.53-0.84) | 0.79 (0.62-1.02) | ||

| Higher | 27.7 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| More than one child younger than 5 years in the household | 0.03 | 0.20 | |||

| No | 20.9 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 16.3 | 0.78 (0.63-0.97) | 0.87 (0.70-1.08) | ||

| Number of prenatal consultations (six or more) | 0.004 | 0.06 | |||

| No | 13.5 | 0.66 (0.49-0.88) | 0.76 (0.57-1.01) | ||

| Yes | 20.6 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Type of delivery | <0.001 | 0.04 | |||

| Normal | 16.5 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Cesarean | 26.1 | 1.58 (1.29-1.94) | 1.25 (1.01-1.55) | ||

| Exclusive breastfeeding (months) | 0.06 | 0.58 | |||

| < 1 | 18.4 | 0.76 (0.58-1.00) | 0.90 (0.69-1.17) | ||

| 1 to 3.9 | 17.1 | 0.71 (0.52-0.96) | 0.86 (0.63-1.15) | ||

| ≥ 4 | 24.2 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Child had a consultation in the last three months | 0.31 | 0.52 | |||

| No | 18.2 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 20.2 | 1.11 (0.91-1.36) | 1.07 (0.88-1.30) | ||

PR, prevalence ratio.

This study showed high prevalence of excess weight and stunting. Important associations as risk factor were found, highlighting stunting with the mother's low level of schooling, low income, lower socioeconomic status, and less than six prenatal consultations. In relation to excess weight, adolescent mother and cesarean section were associated as risk factors, whereas low maternal education and socioeconomic level were associated as protective factors.

The study showed results that demonstrated some specificity, as they were obtained from a homogeneous sample of individuals of low socioeconomic level, living in the semi-arid region of the state of Piauí, Brazil, which is one of the states with the worst social conditions.

The decline in malnutrition is already occurring in this region. The deficit in weight for age was less than 3% (data not shown), which demonstrates that the values are within the normal range, characterizing a change in the epidemiological profile associated with the nutrition transition, where the nutritional deficit problem is replaced by excess weight.5

As positive points, this study includes a seldom studied and underprivileged population due to its geographical location, far from the state capital and difficult to reach. There have been few studies that assessed anthropometric extremes and, in this sample, children in two extremes were analyzed: stunting and excess weight, indicating a stage of nutritional transition.

As a limitation, due to the cross-sectional design of the study, the phenomenon of reverse causality in some associations cannot be dismissed, such as breastfeeding and consultation in the past three months.

The prevalence of stunting found was 10.9%, similar to the study of Saldiva et al.,10 conducted in the semiarid region of the northeast of Rio Grande do Norte, with a prevalence of 9.9%. The two portray socioeconomic inequalities and lack of access to basic health care and social assistance, and make these areas priority regions for efforts directed at the normalization of these childhood deficits. The unassisted children from these regions become vulnerable to interruption and/or delay in their full development, as persistent nutritional deficiencies in childhood impair weight initially and then slow growth, finally affecting height.11

An association was found between stunting and low maternal education. In the state of Pernambuco, the prevalence of stunting was 8.7% in 2006, which was also associated with lower maternal education.11 Maternal education has been identified as a factor associated with childhood growth.12,13 In the study by Menezes et al., it was identified that children of mothers with less than four years of study have twice the chance of having stunted growth.14

The way mothers devote their attention to their children, both directly and through caregivers, as well as their access to health services, are influenced by the level of schooling. A mother with higher level of schooling provides better care to her children due to increased knowledge, and information and access to health care services are influenced by the level of schooling.15

Socioeconomic level (measured by the consumer goods index) was associated as a risk factor for stunting. It was observed that the difference in the prevalence of stunting between the extremes of purchasing power classes is about three-fold, with concentration of growth retardation in children from the poorer classes.11 In this study, the prevalence of stunting was approximately two-fold higher among the poor, when compared to children with higher socioeconomic status.

Stunting was more prevalent when there was more than one child younger than 5 years living in the same household (13.6% versus 9.1%), which can be attributed to low socioeconomic status and the fact of having to share the food with the other family members. These associations show that, even in a poor region, children with younger siblings have their physical development impaired, even after adjusting for other socioeconomic variables.

Another important association was that between fewer prenatal care consultations of the mother and child stunting. This can occur due to the importance of pregnancy on child development. New evidence further reinforces the importance of women's nutritional status and their monitoring at the time of conception and during pregnancy to ensure fetal growth and healthy development of the child, considering that 32 million children are born small for gestational age annually, which represents 27% of all births in developing countries.1 These data emphasize the importance of prenatal care for maternal and child health.

The prevalence of excess weight was 19.1%. There are studies associating childhood obesity to several unfavorable outcomes in adulthood, especially asthma, hypertension, diabetes, coronary heart disease, and some types of cancer, e.g., colorectal and kidney neoplasms.15–17

The highest prevalence of excess weight was in the urban areas (24.8% versus 14.7% in rural areas); the unadjusted analysis showed that living in rural areas was a protective factor, but this association was lost in the adjusted analysis. Traditionally, individuals living in the countryside, especially in rural areas, are more susceptible to nutritional deficits, particularly children. However, in recent years, with the accelerated rate of decrease in malnutrition and increase in obesity, this evidence has diminished,11 as it occurred in the present study after the adjusted analysis.

Adolescent mothers (13-19 years) were more likely to have children with excess weight, and low maternal education was a protective factor for this excess. Studies have shown that maternal age at childbirth ≤ 20 years is a determinant of excess weight.1,17 It is emphasized that the mother is the link between the child and the environment they live in. If the mother is herself at an age of conflicts, discoveries, and transformations that occur in adolescence, these factors could also reflect on the diet and health of her child.

There was a direct association between excess weight and economic status. It is assumed that children with better socioeconomic status have greater access to certain high-calorie foods and sometimes, more expensive ones, as well as greater diversity of food in their homes. This could stimulate weight gain in this group.

It was also verified that mothers who had a cesarean delivery had an approximately 60% higher chance in the unadjusted and 25% in the adjusted analysis of having children with excess weight. A similar result was verified in a study by Xavier et al.,18 in which among the obese group of children, 66.7% reported birth by cesarean section, and among those with overweight, 55.6% reported birth by cesarean section.

Considering the data from this study, it can be concluded that the changes in the country over the years, such as the creation of the family allowance program, the minimum wage increases, improving the income distribution in some regions, and other government programs, helped in the transformation of the Brazilian economy. In this scenario, it can be observed that people are rising from poverty and purchasing more goods, and improving their status regarding living conditions and food, which may explain the decrease in the rates of Brazilian malnutrition and increased overweight/obesity rates.

Attention should be paid so that the economic growth can also be accompanied by public policies targeting health education of the population and the implementation of programs that encourage adequate nutrition. Knowing the nutritional status of children in this region and associated factors will make it possible to draw a plan of nutritional control and guide these families to develop healthier habits. It is noteworthy that stunting, although decreasing, is still high (10.9%), while the prevalence of overweight (19.1%) has exceeded the percentage expected for a normal population, which would be approximately 16%.

FundingThe study was supported by the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) and the City Hall of the municipalities studied, Anísio de Abreu and Caracol, Piauí.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Ramos CV, Dumith SC, César JA. Prevalence and factors associated with stunting and excess weight in children aged 0-5 years from the Brazilian semi-arid region. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2015;91:175–82.