To investigate the prevalence and factors associated with no intention to exclusively breastfeed for the first 6 months of life in a sample of women in the first 24 h postpartum during the hospital stay.

MethodsCross-sectional study with data from screening phase of a birth cohort. The proportion of mothers who did not intend to breastfeed exclusively for 6 months (primary outcome) derived from a negative response to the question “Would you be willing to try to breastfeed exclusively for the first 6 months?”, in an interview conducted by previously trained interviewers. Crude and adjusted prevalence ratios (PR) with 95% confidence intervals were obtained by Poisson regression with robust variance.

ResultsA total of 2964 postpartum women were interviewed. The overall prevalence of mothers who did not intend to breastfeed exclusively for 6 months was 17.8% (16.4−19.1%). After adjusting for maternal age and type of pregnancy (singleton or multiple), no intention to exclusively breastfeed was higher in mothers with a monthly household income < 3 minimum wages (PR, 1.64; 1.35−1.98) and in those who intended to smoke 4−7 days/week after delivery (PR, 1.42; 1.11−1.83). The presence of significant newborn morbidity (PR, 0.32; 0.19−0.54) and intention to breastfeed up to 12 months (PR, 0.46; 0.38−0.55) had a protective effect against not intending to breastfeed exclusively for 6 months.

ConclusionsApproximately 1 in every 5 mothers did not intend to breastfeed exclusively for 6 months. Strategies aimed at promoting exclusive breastfeeding should focus attention on mothers from lower economic strata and smokers.

Breastfeeding is important for the formation of an emotional bond between mother and infant. In addition to being crucial for maternal and child mental health, it is also associated with short- and long-term health benefits.1,2 The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends initiating breastfeeding within the first hour after birth, followed by exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of life and continued breastfeeding with complementary foods up to 2 years of age.3 Children who are breastfed have lower rates of morbidity and mortality from acute infectious diseases, a lower risk of developing non-communicable diseases, such as obesity and type 1 and 2 diabetes, and a higher level of intelligence.1,4 For mothers, breastfeeding accelerates postpartum recovery and gives protection against breast and ovarian cancer and type 2 diabetes.1 The Lives Saved Tool, a modeling software used to estimate the impact of scaling up effective interventions on mortality, estimates that 823 000 child deaths could be prevented every year if breastfeeding were scaled up to near-universal levels.5 Despite all the advantages, the prevalence of breastfeeding is below the recommended level. Recent WHO data show that 2 in every 3 infants are not exclusively breastfed during the first 6 months of life.6

According to preliminary results of the National Study of Child Food and Nutrition of the Brazilian Ministry of Health published in 2020, the rate of exclusive breastfeeding in infants younger than 6 months in Brazil is 45.7%.7 Although this prevalence does not meet the goals established by the World Health Assembly, which aims to increase this rate to 50% by 2025,8 the prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding in Brazil shows an upward trend; in 2013, the rate was 36.6%.9 This increase can be explained by efforts to advertise and reinforce the benefits of breastfeeding through campaigns and programs, such as the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI), which was launched in 1991 by WHO and the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) and introduced in Brazil in 1992 to promote, protect, and support breastfeeding.10

Different maternal factors may be related to successful breastfeeding, such as knowledge of breastfeeding benefits, prenatal breastfeeding intention, previous breastfeeding experience, smoking, occupation, socioeconomic status, and age.1,11 A population-based cohort in the United Kingdom with more than 10 000 women showed that the intention to breastfeed was stronger than maternal demographic characteristics as a predictor of breastfeeding behavior.12 Most studies, however, have sought to identify factors associated with breastfeeding intention, without investigating what influences mothers to not intend to breastfeed. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the prevalence and factors associated with no intention to exclusively breastfeed for the first 6 months of life.

MethodsThis cross-sectional study was performed with data collected in the screening phase of a prospective cohort study entitled “Multi-Centre Body Composition Reference Study (MBCRS),” which has been conducted simultaneously in the cities of Launceston (Australia), Pelotas (Brazil), Bangalore (India), Karachi (Pakistan), and Johannesburg (South Africa), with the purpose of evaluating body composition changes in healthy neonates and infants during the first 2 years of life using stable isotope analysis. The eligibility criteria applied to mothers and children for inclusion in the cohort were a combination of the criteria used in the WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study (MGRS)13 and the INTERGROWTH-21st Project.14

Sample size calculation in the multicenter study determined that 150 infants were needed per participating country, plus 10% to compensate for possible losses. Thus, in Pelotas, we needed to conduct 2964 screening interviews to achieve the required sample size.

In this study only data collected in the four maternity facilities in Pelotas, a city located in the southern region of the state of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, with a population of approximately 343 000 was employed.15 Data were collected in the perinatal period from postpartum women who gave birth between September 2014 and February 2015 and from March to July 2017, regardless of the delivery payment method (through the publicly funded Brazilian Unified Health System, private health insurance, or out-of-pocket). The mothers were interviewed by trained interviewers using a standardized, pretested questionnaire.

The primary outcome was the proportion of mothers who did not intend to breastfeed exclusively for the first 6 months of life, derived from a negative response to the question “Would you be willing to try to breastfeed exclusively for the first 6 months?”. Exclusive breastfeeding was defined as an infant receiving only breast milk from the mother, either directly from the breast or expressed, with no addition of water, tea, or any other liquids, with the exception of drops of vitamins, oral rehydration salts, mineral supplements, or medicines.2

The following independent variables were measured: monthly household income (<3 or ≥3 minimum wages) (minimum wage at the time of the study = 724.00 Reais, Brazilian currency); maternal age (<20 years, 20−29 years, 30−34 years, or ≥35 years); type of pregnancy (singleton or multiple); smoking during pregnancy (average number of days per week that they smoked after learning they were pregnant) (0−3 or 4−7 days per week); intention to smoke after delivery (0−3 or 4−7 days per week); gestational age (<37 or ≥37 weeks); the presence of significant newborn morbidity (need for admission to a neonatal intensive care unit) (yes or no); place of residence (urban or rural area of Pelotas); and intention to continue breastfeeding up to 12 months (yes or no).

Data were analyzed using Stata, version 12.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, USA). For sample description, maternal age was expressed as mean (standard deviation) and categorical variables were expressed as percentages. Initially, we calculated the overall prevalence of mothers who did not intend to breastfeed exclusively for 6 months, adopting a 95% confidence interval (95% CI). We then analyzed the prevalence of mothers who did not intend to breastfeed exclusively for 6 months, with 95% CI, according to the independent variables. Possible associations between independent variables and the outcome were investigated by the chi-square test for heterogeneity of proportions or the test for linear trend, as appropriate. Poisson regression models with robust variance were used to obtain crude and adjusted prevalence ratios (PR) and their respective 95% CI. All independent variables were included in the adjusted analysis and then removed one by one from the model by backward elimination, starting with the variable with the highest p-value. For adjustment purposes, variables with p < 0.20 were kept in the final model. Associations with p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

The original base project was approved in 2014 by the Ethics Committee of the School of Medicine of the Federal University of Pelotas, affiliated with the Brazilian National Research Ethics Committee and National Health Council (approval number 1 199 651). Written informed consent was obtained from the mothers prior to their inclusion in the study.

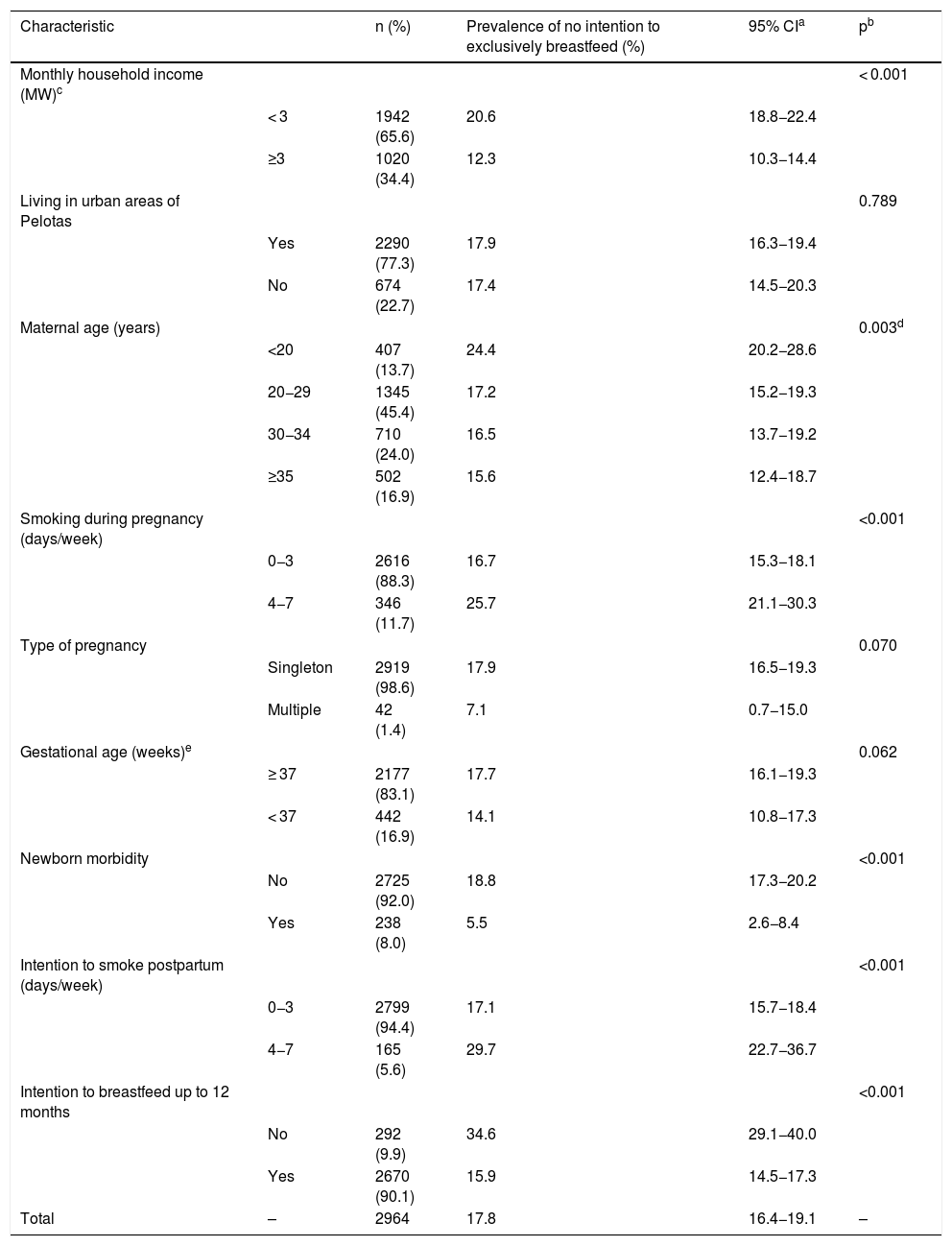

ResultsThe sample consisted of 2964 postpartum women, with a mean age of 27.6 years, ranging from 13 to 47 years. Almost half of all mothers (45.4%) were aged 20–29 years, 65.6% had a monthly household income < 3 minimum wages, and 77.3% lived in urban areas of Pelotas (Table 1). About 12.0% of mothers reported having smoked on average 4−7 days per week during pregnancy, and 5.6% reported intending to smoke 4–7 days per week after delivery. Most women (98.6%) had a singleton pregnancy, with infants born at ≥ 37 weeks’ gestation (83.1%) without morbidity (92.0%). In 90.1% of cases, mothers reported intending to breastfeed up to 12 months (Table 1).

Sample distribution and prevalence of no intention to exclusively breastfeed for the first 6 months of life, according to maternal and child characteristics (n = 2964).

| Characteristic | n (%) | Prevalence of no intention to exclusively breastfeed (%) | 95% CIa | pb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monthly household income (MW)c | < 0.001 | ||||

| < 3 | 1942 (65.6) | 20.6 | 18.8−22.4 | ||

| ≥3 | 1020 (34.4) | 12.3 | 10.3−14.4 | ||

| Living in urban areas of Pelotas | 0.789 | ||||

| Yes | 2290 (77.3) | 17.9 | 16.3−19.4 | ||

| No | 674 (22.7) | 17.4 | 14.5−20.3 | ||

| Maternal age (years) | 0.003d | ||||

| <20 | 407 (13.7) | 24.4 | 20.2−28.6 | ||

| 20−29 | 1345 (45.4) | 17.2 | 15.2−19.3 | ||

| 30−34 | 710 (24.0) | 16.5 | 13.7−19.2 | ||

| ≥35 | 502 (16.9) | 15.6 | 12.4−18.7 | ||

| Smoking during pregnancy (days/week) | <0.001 | ||||

| 0−3 | 2616 (88.3) | 16.7 | 15.3−18.1 | ||

| 4−7 | 346 (11.7) | 25.7 | 21.1−30.3 | ||

| Type of pregnancy | 0.070 | ||||

| Singleton | 2919 (98.6) | 17.9 | 16.5−19.3 | ||

| Multiple | 42 (1.4) | 7.1 | 0.7−15.0 | ||

| Gestational age (weeks)e | 0.062 | ||||

| ≥ 37 | 2177 (83.1) | 17.7 | 16.1−19.3 | ||

| < 37 | 442 (16.9) | 14.1 | 10.8−17.3 | ||

| Newborn morbidity | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 2725 (92.0) | 18.8 | 17.3−20.2 | ||

| Yes | 238 (8.0) | 5.5 | 2.6−8.4 | ||

| Intention to smoke postpartum (days/week) | <0.001 | ||||

| 0−3 | 2799 (94.4) | 17.1 | 15.7−18.4 | ||

| 4−7 | 165 (5.6) | 29.7 | 22.7−36.7 | ||

| Intention to breastfeed up to 12 months | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 292 (9.9) | 34.6 | 29.1−40.0 | ||

| Yes | 2670 (90.1) | 15.9 | 14.5−17.3 | ||

| Total | – | 2964 | 17.8 | 16.4−19.1 | – |

The overall prevalence of mothers who did not intend to breastfeed exclusively for 6 months was 17.8% (95% CI 16.4−19.1%) (Table 1). This rate was higher in mothers with a monthly household income < 3 minimum wages (20.6%; 95% CI, 18.8−22.4%) than in those with a monthly household income ≥ 3 minimum wages (12.3%; 95% CI, 10.3−14.4%) (p < 0.001). Mothers aged ≥ 35 years had a lower prevalence of no intention to exclusively breastfeed than mothers younger than 20 years. The association between maternal age and the outcome was linearly inversed (the older the woman, the lower the prevalence of no intention to exclusively breastfeed for 6 months) (p = 0.003, linear trend test) (Table 1). The intention not to exclusively breastfeed for 6 months was more frequent in mothers who smoked on average 4−7 days per week during pregnancy (25.7%) than in those who did not smoke or who smoked ≤ 3 days per week. Regarding the intention to smoke after delivery, the prevalence of no intention to exclusively breastfeed was also higher in those who intended to smoke 4−7 days per week (29.7%) vs 0−3 days per week (17.1%). The prevalence of no intention to exclusively breastfeed was higher in mothers of infants without newborn morbidity (18.8%) than in mothers of infants requiring admission to the neonatal intensive care unit (5.5%). Mothers who did not intend to breastfeed up to 12 months showed a higher prevalence of also having no intention to exclusively breastfeed for the first 6 months of life (34.6%) than those who intended to breastfeed up to 12 months (15.9%) (Table 1).

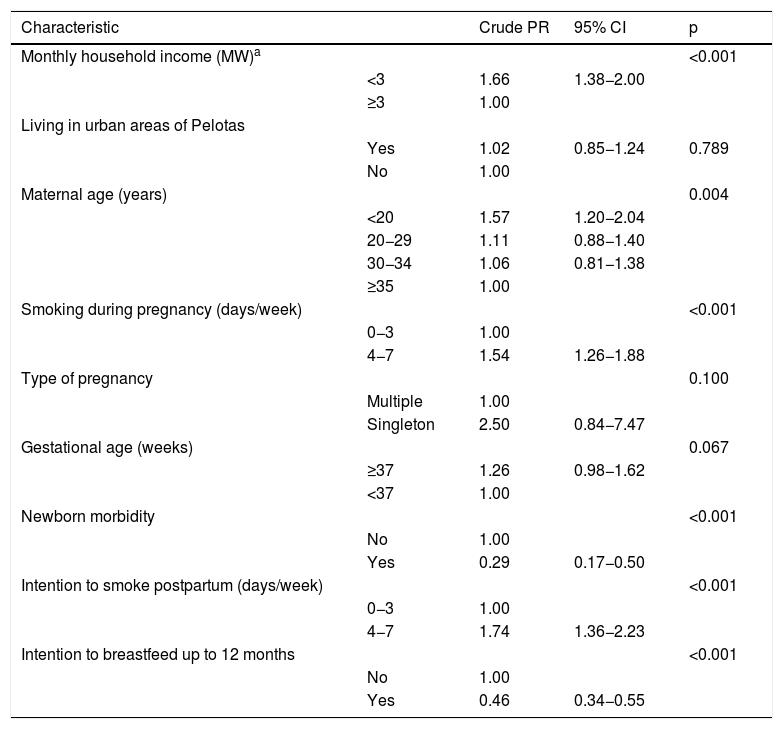

Table 2 shows the crude PRs for no intention to exclusively breastfeed for the first 6 months of life, according to maternal and child characteristics. The following variables were positively associated with the outcome: monthly household income, with a 66% higher prevalence of no intention to exclusively breastfeed in women with an income < 3 minimum wages; maternal age, with a 57% higher prevalence of no intention to exclusively breastfeed in women younger than 20 years; and smoking on average 4−7 days/week during pregnancy and intention to smoke 4−7 days/week after delivery, with, respectively, a 54% and 74% higher prevalence of no intention to exclusively breastfeed than their counterparts. Variables negatively associated with the outcome included the presence of significant newborn morbidity, with a 71% lower prevalence of no intention to exclusively breastfeed in mothers of infants with morbidity vs healthy infants, and intention to breastfeed up to 12 months, with a 54% lower prevalence in mothers who intended vs those who did not intend to breastfeed up to 12 months. Place of residence, type of pregnancy, and gestational age had no statistically significant association with the outcome (Table 2).

Crude prevalence ratios (PR), with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI), for no intention to exclusively breastfeed for the first 6 months of life, according to maternal and child characteristics.

| Characteristic | Crude PR | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monthly household income (MW)a | <0.001 | |||

| <3 | 1.66 | 1.38−2.00 | ||

| ≥3 | 1.00 | |||

| Living in urban areas of Pelotas | ||||

| Yes | 1.02 | 0.85−1.24 | 0.789 | |

| No | 1.00 | |||

| Maternal age (years) | 0.004 | |||

| <20 | 1.57 | 1.20−2.04 | ||

| 20−29 | 1.11 | 0.88−1.40 | ||

| 30−34 | 1.06 | 0.81−1.38 | ||

| ≥35 | 1.00 | |||

| Smoking during pregnancy (days/week) | <0.001 | |||

| 0−3 | 1.00 | |||

| 4−7 | 1.54 | 1.26−1.88 | ||

| Type of pregnancy | 0.100 | |||

| Multiple | 1.00 | |||

| Singleton | 2.50 | 0.84−7.47 | ||

| Gestational age (weeks) | 0.067 | |||

| ≥37 | 1.26 | 0.98−1.62 | ||

| <37 | 1.00 | |||

| Newborn morbidity | <0.001 | |||

| No | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 0.29 | 0.17−0.50 | ||

| Intention to smoke postpartum (days/week) | <0.001 | |||

| 0−3 | 1.00 | |||

| 4−7 | 1.74 | 1.36−2.23 | ||

| Intention to breastfeed up to 12 months | <0.001 | |||

| No | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 0.46 | 0.34−0.55 |

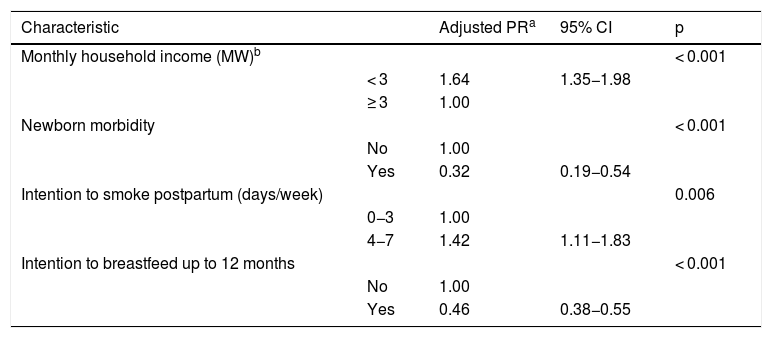

Maternal age and type of gestation were associated with no intention of exclusively breastfeeding up to six months at p-values 0.156 and 0.120, respectively, and were then maintained in the final model for adjustment purposes. In the multivariate regression analysis (Table 3), mothers with a monthly household income < 3 minimum wages had a 64% higher probability of not intending to breastfeed exclusively for 6 months (PR, 1.64; 95% CI, 1.35–19.8; p < 0.001) than mothers with an income ≥ 3 minimum wages. Mothers who intended to smoke 4−7 days per week after delivery had a 42% higher probability of not intending to breastfeed exclusively for 6 months than their counterparts (PR, 1.42; 95% CI, 1.11−1.83; p < 0.006). Conversely, mothers of infants with significant newborn morbidity and those who intended to breastfeed up to 12 months had, respectively, a 68% and 54% lower probability of not intending to breastfeed exclusively for 6 months than their counterparts (Table 3).

Adjusted prevalence ratios (PR), with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI), for no intention to exclusively breastfeed for the first 6 months of life.

| Characteristic | Adjusted PRa | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monthly household income (MW)b | < 0.001 | |||

| < 3 | 1.64 | 1.35−1.98 | ||

| ≥ 3 | 1.00 | |||

| Newborn morbidity | < 0.001 | |||

| No | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 0.32 | 0.19−0.54 | ||

| Intention to smoke postpartum (days/week) | 0.006 | |||

| 0−3 | 1.00 | |||

| 4−7 | 1.42 | 1.11−1.83 | ||

| Intention to breastfeed up to 12 months | < 0.001 | |||

| No | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 0.46 | 0.38−0.55 |

This study identified a 17.8% prevalence of no intention to exclusively breastfeed for the first 6 months of life among mothers interviewed in the immediate postpartum period. Adjusted analyses showed that low household income and intention to smoke heavily were positively associated with no intention to exclusively breastfeed for 6 months, whereas newborn morbidity and intention to breastfeed up to 12 months were protective against this outcome.

Brazil is often cited as a model country when it comes to investing in the protection and promotion of breastfeeding, which is supported by the observed increase in the rate of exclusive breastfeeding in infants younger than 6 months.9,16,17 This increase occurred during a period of urbanization in the country and of greater participation of women in the labor market, which makes the result even more significant. In addition to national breastfeeding support initiatives, the city of Pelotas, in particular, has specific local policies and research projects focused on the benefits of breastfeeding.1,18 The local population’s acquaintance with the topic, and consequently with its importance, may be one of the factors explaining the high prevalence of intention to breastfeed up to 12 months (90.1%) and of exclusively breastfeed for 6 months (82.2%) found in this study. Despite this, there is still room for improvement.

Another positive association with exclusive breastfeeding was the presence of newborn morbidity. Mothers of infants with newborn morbidity were more willing to try to breastfeed exclusively for 6 months than mothers of healthy infants. A possible explanation for this finding is that it may reflect the idea that women who have children with morbidities believe that their babies are more susceptible to diseases and, therefore, consider exclusive breastfeeding a form of protection; however, further studies are needed to support this hypothesis.

The intention not to exclusively breastfeed was greater in women with lower household income. This finding may be explained by the fact that women with higher household income often have greater access to information on breastfeeding benefits.19 However, there is no consensus in the literature regarding this association. Some studies found a positive relationship,20 while others detected no association.21,22 Household income can influence maternal lifestyle in different ways. Therefore, this variable may be associated with different confounding factors, including the need to return to work, which makes it difficult to identify a consistent relationship with the intention to exclusively breastfeed for 6 months in the different studies.

Maternal smoking habits were also an important factor in the intention not to exclusively breastfeed. Women who reported intending to smoke 4−7 days per week in the postpartum period had a higher probability of not intending to breastfeed exclusively for 6 months. These data are in line with the results reported in a cohort study conducted in the United Kingdom, in which smokers were more likely to discontinue breastfeeding than nonsmokers.23 A nationwide sample of 72 861 mothers selected at random in the United States showed that women who smoked in the postpartum period and who also suffered from socioeconomic disadvantages also had a higher likelihood of not continuing exclusive breastfeeding.24 Tobacco smoke changes maternal hormone levels, which are associated with reduced lactation, possibly because nicotine blocks the suckling-induced rise in circulating prolactin - hormone promoting lactation by stimulating the growth of mammary glands.25 Additionally, maternal smoking and breastfeeding increase the absorption of nicotine by the infant compared to this only being exposed to tobacco smoke. Newborns of smoking mothers manifest delayed initiation of the sucking reflex and lower sucking pressure during breastfeeding. These differences in breast stimulation and breast emptying frequency may also disturb endocrine reactions contributing to reduced milk production in mothers who smoke.25 Thus, tobacco control measures are still important in this population. Multidisciplinary approaches to prevent tobacco use are needed, as well as the provision of smoking cessation assistance.

Our study has some limitations that need to be addressed. Because this study used data from the screening phase of a multicenter study, some maternal characteristics potentially associated with no intention to exclusively breastfeed were not available and could not be investigated, such as full-time maternal employment/return to work maternal weight/obesity, low education, parity, living with a partner, type of delivery, depression or anxiety symptoms during gestation, sex of the newborn, birth weight, gestational age, prior lactation counseling, previous breastfeeding experience, and knowledge of breastfeeding benefits.10,19,26–28

In addition, the method of data collection may have led to bias, since each participant met with the interviewer on an individual basis to answer the questionnaire. Because, in general, the benefits of breastfeeding are well known, the participants may have felt embarrassed to reveal that they had no intention to breastfeed, which could result in an information bias that, in turn, would reduce the prevalence of the outcome. Finally, the study presented data from participants living in the same city, with a strong tradition of studies on breastfeeding, which may limit the ability to generalize the results.

Strengths of this study include previous training of interviewers and standardized application of the questionnaire, in addition to daily supervision of data collection by a fieldwork coordinator. Also, this study can serve as a basis for future research, thus contributing to the analysis of the trend toward exclusive breastfeeding up to 6 months in the city of Pelotas.

Even with policies to raise awareness of breastfeeding benefits for both maternal and child health, we found a relatively high prevalence of no intention to exclusively breastfeed for 6 months: approximately 1 in every 5 mothers reported not intending to exclusively breastfeed for the first 6 months of life. Low household income and smoking proved to be important factors in a mother’s decision to not intend to exclusively breastfeed for the first 6 months of life. Strategies aimed at promoting breastfeeding should focus attention on mothers from lower economic strata and smokers.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The multicenter study was funded by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), the National Research Council of Brazil (CNPq), and Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (Brazilian Federal Agency for Support and Evaluation of Graduate Education — CAPES) Finance Code 001.

Study conducted at Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul, Programa de Pós-graduação em Pediatria e Saúde da Criança, Disciplina Redação Científica, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil.